Published online Mar 26, 2025. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v17.i3.101454

Revised: October 15, 2024

Accepted: January 15, 2025

Published online: March 26, 2025

Processing time: 187 Days and 3.4 Hours

Heart disease remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, with existing treatments often failing to effectively restore damaged myocardium. Human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and their derivatives offer promising therapeutic options; however, challenges such as low retention, engraftment issues, and tumorigenic risks hinder their clinical utility. Recent focus has shifted to exosomes (exos) - nanoscale vesicles that facilitate intercellular communication - as a safer and more versatile alternative. Understanding the specific mechanisms and comparative efficacy of exos from hiPSCs vs hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) is crucial for advancing cardiac repair therapies.

To evaluate and compare the therapeutic efficacy of exos secreted by hiPSCs and hiPSC-CMs in cardiac repair, and to elucidate the role of microRNA 21-5p (miR-21-5p) in the observed effects.

We differentiated hiPSCs into CMs using small molecule methods and characterized the cells and their exos.

Our findings indicate that hiPSC-CMs and their exos enhanced cardiac function, reduced infarct size, and decreased myocardial fibrosis in a murine myocardial infarction model. Notably, hiPSC-CM exos outperformed hiPSC-CM cell therapy, showing improved ejection fraction and reduced apoptosis. We identified miR-21-5p, a microRNA in hiPSC-CM exos, as crucial for CM survival. Exos with miR-21-5p were absorbed by AC16 cells, suggesting a mechanism for their cytoprotective effects.

Overall, hiPSC-CM exos could serve as a potent therapeutic agent for myocardial repair, laying the groundwork for future research into exos as a treatment for ischemic heart disease.

Core Tip: This study explored human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) and their exosomes (exos) for myocardial infarction (MI) repair. Despite issues with hiPSC-CMs, exos are promising due to low immunogenicity. By differentiating hiPSCs and characterizing, it was found that they improved cardiac function in a murine MI model. hiPSC-CMs exos are superior, with microRNA 21-5p being key. Thus, they may be a strong agent for myocardial repair and inspire further research on exo treatment for heart disease.

- Citation: Jin JJ, Liu RH, Chen JY, Wang K, Han JY, Nie DS, Gong YQ, Lin B, Weng GX. MiR-21-5p-enriched exosomes from hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes exhibit superior cardiac repair efficacy compared to hiPSC-derived exosomes in a murine MI model. World J Stem Cells 2025; 17(3): 101454

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v17/i3/101454.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v17.i3.101454

Myocardial infarction (MI), more commonly referred to as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow to a section of the heart is severely curtailed or obstructed, leading to damage or death of the heart muscle cells. It stands as a primary cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and imposes a considerable healthcare burden due to its profound effects on the quality of life and the economic costs associated with treatment and recovery[1]. Current therapies for heart diseases primarily slow progression, yet they fall short of repairing damaged myocardium. Human pluripotent stem cells (SCs) exhibit immense potential as a cellular source for cardiac repair due to their boundless self-renewal capacity and their potential to differentiate into cardiomyocytes (CMs)[2,3]. However, challenges such as low cell retention and engraftment rates, along with the risks of tumorigenesis and ventricular arrhythmia, impede their clinical application[4]. Studies have shown that human-induced pluripotent SC (hiPSC)-derived CMs (hiPSC-CMs) can booster myocardial function, mitigate ventricular remodeling, and curtail mortality in rats with MI. Transplanted hiPSC-CMs not only achieve electromechanical integration with the host tissue[5-8] but also secrete cytokines that foster angiogenesis and survival of the injured muscle[9]. These improvements in cardiac function have largely been attributed to paracrine factors[10,11].

Exosomes (exos) are vital mediators of intercellular communication, characterized as small membrane vesicles that carry a variety of biomolecules[12]. Studies have indicated that exos can modulate the survival, proliferation, and apo

MiR-21-5p is an miRNA that is upregulated in various cardiovascular diseases and has a particularly prominent role in MI[17,18]. In MI, miR-21-5p is involved in processes such as apoptosis, fibrosis, and angiogenesis of CMs by regulating multiple target genes. For instance, miR-21-5p can suppress the expression of certain anti-apoptotic genes, thereby promoting the death of CMs[19,20]. Furthermore, miR-21-5p is involved in the regulation of the expression of angio

In this study, we explored the therapeutic potential of hiPSC-CM exos in a murine model of MI.

HiPSCs were obtained from Nuwacell Biotechnologies Co., Ltd. (Anhui, China) and were genetically labeled with green fluorescent protein (Luc-GFP). HiPSCs were cultured in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C in ncEpic (Nuwacell) iPSC medium (Nuwacell), and prepared using serum-free basal medium mixed with additives in a ratio of 1:125. The complete culture medium was stored at 4 °C and could be used for up to 4 weeks, ensuring that it was equilibrated to room temperature before use.

HiPSCs were induced to CMs by selective modulation of the Wnt pathway in a monolayer culture using the CardioEasy Kit (Cellapy Biotechnology, Beijing, China) as previously reported[22]. In brief, the medium was changed to Induction Medium I when the hiPSCs reached about 80% confluency. After 48 hours, hiPSCs were cultured in Induction Medium II for another 48 hours and then in Induction Medium III, with the media changed every other day. On days 7-9, the cells began to contract. Then hiPSC-CMs were glucose-starved for 3 days by CardioEasy purification. Afterward, the media were replaced with a maintenance medium for human myocardial cells (Cellapy) and were changed every other day. HiPSC-CMs were identified by immunofluorescence staining. For cell recovery, a 10 μM culture medium was prepared by mixing the complete culture medium with Nuwacell™ blebbistatin at a ratio of 4000:1. The culture medium for the first day of cell recovery and passaging was supplemented with 10 μM blebbistatin to support cell viability and proliferation.

The myocardial differentiation additives were stored at -20 °C and thawed at 4 °C before use. After thawing, the additives were briefly centrifuged to ensure homogeneity. The differentiation reagents were prepared by mixing the myocardial differentiation additives with the basal medium at a ratio of 1:49. To avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, the thawed additives were aliquoted according to usage and stored at -20 °C. The prepared differentiation reagents could be stored at 4 °C and used within 1 month.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed in a confocal dish, with hiPSC-CMs fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. The fixed cells were washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST), and then the samples were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes at room temperature and blocked in 10% goat serum to reduce nonspecific binding. The cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with cardiac troponin T (cTNT, 1:100; R&D Systems, Minnesota, MN, United States), 2v isoform of myosin light chain (1:100; ProteinTech, Chicago, IL, United States), and NK2 homeobox 5 (1:200; Abcam, United Kingdom) monoclonal antibodies and then incubated with the appropriate anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, TX, United States) conjugated to Alexa Flour 647. The above-mentioned secondary antibodies were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour in the dark. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI staining solution and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. The cells were visualized using the inverted Leica DMi8 microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Confocal imaging (TCSP8; Leica) and high-content imaging (ImageXpress Micro Confocal; Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, United States) were used to investigate the morphology of hiPSC-CMs and assess their contractile function. The microelectrode array platform was utilized to evaluate the cardiac electrophysiological function of hiPSC-CMs.

Purified exos secreted by hiPSC- and hiPSC-CM-derived cells were isolated using an exo isolation kit (Umibio, Shanghai, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The exo pellet was resuspended in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) with the volume indexed to the number of cells from which the exos/microvesicles were derived (100 μL DPBS/5 × 105 cells). The protein content of exos was assessed using the BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and western blotting was used to evaluate the expression of exo-specific markers (cluster of differentiation 63 [CD63] and tumor susceptibility gene 101 [TSG101]). The concentration and size of exos were measured using nanoparticle tracking analysis (Zetaview-PMX120-Z; Particle Metrix, Inning am Ammersee, Germany), and the morphology of the exos was assessed by transmission electron microscopy (JEM1400; JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

The purified exos were mixed with the lysate in equal volumes, incubated on ice for 30 minutes, and then centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new Eppendorf (EP) tube, and the protein concentration was determined using the BCA method. Subsequently, 5 × loading buffer was added to the supernatant, mixed well, and boiled at 100 °C for 5 minutes. The samples were separated on a 5% stacking gel and 12% resolving gel, and then the proteins were electrotransferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes at 300 mA for 50 minutes on ice. The polyvinylidene fluoride membrane was blocked in a solution containing 5% skim milk in poly(butylene succinate-butylene terephthalate) (PBST) at room temperature for 1 hour. Primary antibodies including β-actin (1:2000), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) (1:2000), Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) (1:2000), HIF-1α (1:2000), CD63 (1:1000), and TSG101 (1:1000) were added and incubated at 4 °C overnight. After washing three times with PBST, horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (diluted 1:10000) was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Finally, after washing three times with PBST, enhanced chemiluminescence reagent was applied and images were captured using the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States).

The acute MI model was developed as previously described[23-26]. In brief, adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (about 250 g) were initially anesthetized with chloral hydrate (300 mg/kg) and maintained under 2.0% lidocaine anesthesia. The rats were connected to a rodent ventilator via tracheal intubation. The left anterior descending coronary artery was per

Post-MI, M-mode echocardiography was administered at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days by an investigator unaware of the experimental protocols. Standard M-mode parameters, including left ventricular internal diameter in end-diastole and end-systole internal diameters, were meticulously measured to calculate the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS) in accordance with the guidelines set by the American Society of Echocardiography recommendations[27]. All parameters were presented as the average of three beats.

In evaluating the presence of iPSC-Luc-GFP and hiPSC-CM-Luc-GFP in rats, bioluminescence detection was performed using the IVIS Lumina II detector (PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA, United States) on days 0, 3, and 7 post-surgery. Rats were administered an intraperitoneal injection of 3% pentobarbital sodium for anesthesia (0.1 mL/100 g), followed by imaging using the IVIS Lumina X5 detector after injection of D-luciferin (150 mg/kg).

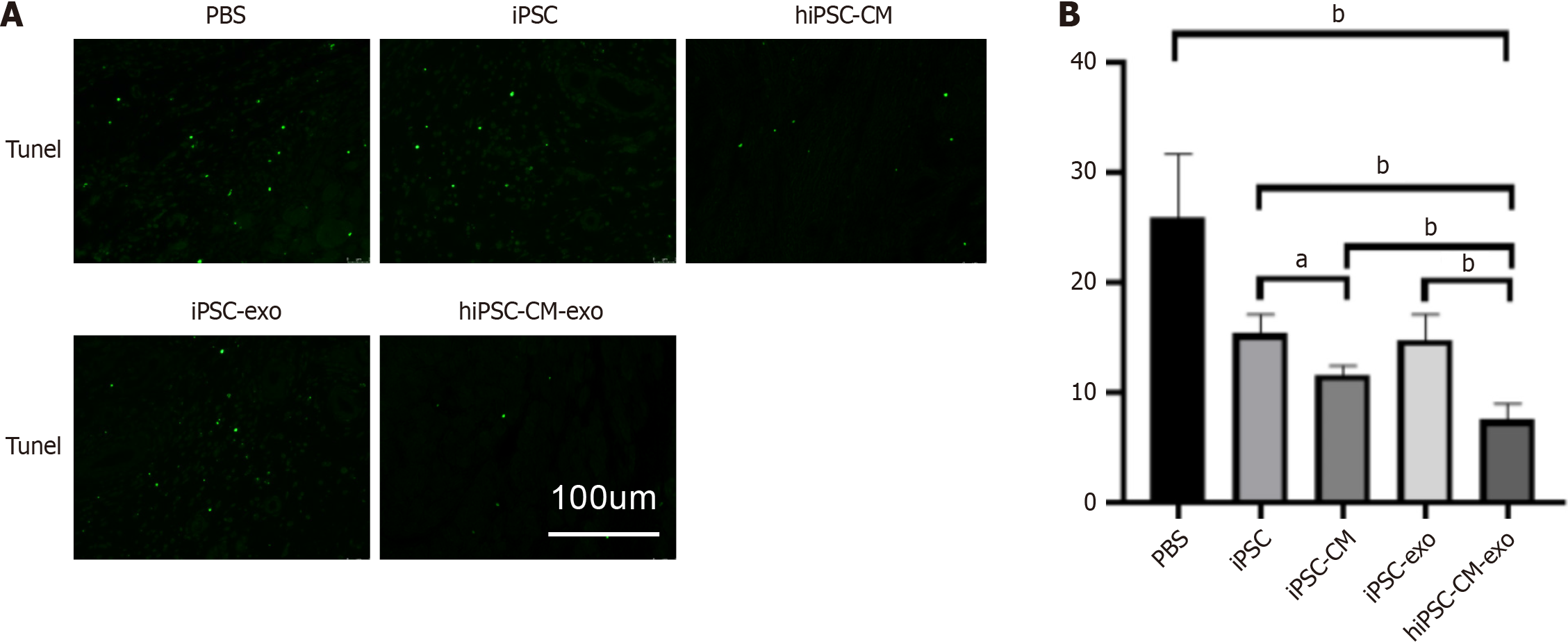

In quantifying apoptotic CMs in a rat model of MI, the hearts of three rats were harvested 3 days post-MI. The rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of 3% pentobarbital sodium (0.1 mL/100 g) for heart extraction. The hearts were fixed in 4% polyformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, paraffin blocks were sectioned into 5 μm slides for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay. The TUNEL assay was performed using a fluorescein (FITC) TUNEL Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DAPI was used for nuclear counterstaining. Under the Leica DMi8 microscope, five positive view fields were photographed for each section. ImageJ was used for image analysis. On the 28th day post-model establishment, four rats from each group were selected randomly. The hearts were fixed in paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, paraffin blocks were sectioned into 5 μm slides. After slicing, the heart tissue sections were deparaffinized and dehydrated, followed by staining. The pathological changes of myocardial tissues were evaluated by immunohistochemical analysis.

Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized with xylene and graded alcohols, followed by PBS rinses. After overnight soaking in Masson A solution, sections were treated with Masson B and C mixtures, hydrochloric acid ethanol, and Masson D and E solutions, and then differentiated in glacial acetic acid and dehydrated in ethanol and xylene. Finally, sections were neutral gum sealed, observed under a microscope, and the degree of fibrosis was quantified using ImageJ software (https://imagej.net/software/imagej/) based on histological analysis.

On the 28th day following model establishment, three rats from each group were randomly selected. The rats were anesthetized using intraperitoneal injection of 3% pentobarbital sodium (0.1 mL/100 g) to facilitate heart extraction. PBS was used to wash away blood stains. The heart was dried with gauze and then frozen at -80 °C in a refrigerator for 15 minutes. Subsequently, the heart was sliced into serial sections along with a surgical ligature and then immersed in 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazoliumchloride solution (Sigma Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, United States). The sections were incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 20 minutes. After staining, photographs were taken. The brick red coloration denoted a normal area, whereas the gray-white color represented the MI area. ImageJ was utilized to calculate the infarction size. The infarction percentage (%) was determined by dividing the infarction area by the total area of the heart’s cutting surface and multiplying by 100%.

The supernatants of hiPSC and hiPSC-CM cells were collected to extract extracellular vesicles, and sent to Shu Pu (Shanghai, China) Biotechnologies LLC (DBA Aksomics) for miRNA sequencing. Sequencing of miRNAs in extracellular vesicles was performed using the Illumina NextSeq500 sequencer.

HiPSC and hiPSC-CM cell supernatants were collected, and exo suspensions were isolated by ultracentrifugation. Then 1 mL TRIzol reagent was added to the exo pellet in an EP tube and exos were lysed by repeated pipetting on ice for 10 minutes. After lysis, 200 μL chloroform was added and mixed thoroughly by vigorous inversion. The mixture was incubated on ice for 5 minutes before centrifuging at 12000 rpm for 15 minutes. Next, the top aqueous layer was carefully transferred to a new EP tube, followed by the addition of an equal volume of isopropanol. Then the tube was inverted 10 times and incubated on ice for 10 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, the RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol, and centrifuged again at 7500 rpm for 10 minutes. The liquid was discarded, and the pellet was air dried. The RNA was resuspended in 30 μL DEPC-treated water. miRNA reverse transcription was conducted using the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was conducted using the Novo Start SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus (E096-01B; Novoprotein, Scientific Inc., Shanghai, China) on the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Beta-actin served as an endogenous control for normalizing the expression levels of the target genes. The primers utilized in this study are detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

A total of 2 × 105 cells were seeded in each well of a 6-well plate with antibiotic-free medium 1 day prior to transfection, ensuring 50% confluence at transfection time and preventing cell clumping. A total of 10 μL miR-21-5p mimic or inhibitor was diluted in 250 μL Opti-MEM, and 6 μL Lipofectamine 3000 was diluted in another 250 μL Opti-MEM. The solution was mixed gently and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. The diluted miRNA and transfection reagent were combined, mixed, and incubated for 20 minutes. The medium was replaced with 1.5 mL antibiotic-free complete medium, and 500 μL transfection complex was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24-48 hours. Then the medium was replaced with complete medium after 4-6 hours if needed.

AC16 CMs were plated at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate with antibiotic-free complete medium. Transfection was performed when cells reached about 50% confluence. The medium was replaced with fresh antibiotic-free complete medium 6 hours post-transfection, and then switched to glucose-free Dulbecco’s Eagle Modified Medium with 500 μM cobalt chloride (CoCl2) after 48 hours for an additional 24 hours. After this incubation period, the cells were harvested by trypsinization without EDTA, centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 minutes, and washed with PBS, after which a working solution of 1 × binding buffer was prepared. Detach cells with trypsin, stop the digestion with culture medium, transfer to a centrifuge tube, and wash with pre-chilled PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in 1 × binding buffer to a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL, and then 100 μL of this suspension was transferred to a new tube, followed by the addition of 5 μL Annexin V-FITC and 5 μL PI. The solution was mixed gently, and incubated in the dark for 15 minutes. Finally, 400 μL of 1 × binding buffer was added to each tube for flow cytometry analysis.

The data were meticulously analyzed and visualized using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). All data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test for comparisons between two groups and one-way analysis of variance for assessments involving more than two groups. The significance levels were aP < 0.05 and bP < 0.01.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Academy of Medical Sciences (Approval No. DL2021-09; Fuzhou, China).

All animal protocols were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Animal Experiments of Fujian Academy of Medical Sciences (Approval No. DL2021-09).

To obtain highly pure and relatively mature CMs, we employed small molecule-based methods for myocardial differentiation provided by Nuwacell Biotechnologies Co., Ltd. These cells were genetically labeled with GFP. During the initial stages of differentiation (days 0-2), the agglomerated hiPSC colonies displayed a typical morphology characterized by a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio (Supplementary Figure 1A). By days 8-9, a notable subset of cells had begun to exhibit rhythmic beating motions, reminiscent of wave-like patterns (Video 1). Following a 2-day purification process on day 14, the CMs demonstrated enhanced contractions compared to the earlier stages (Video 2). The purified, differentiated CMs presented distinct morphological features associated with these cells, including a large cell volume, irregular shape, and less pronounced nucleocytoplasmic ratio (Supplementary Figure 1B). Confocal microscopy disclosed interconnected clusters of CMs displaying synchronized beating, a testament to their robust contractile function (Supplementary Figure 1C, Video 3). High-content imaging revealed a monolayer growth pattern, with individual cells contracting centripetally at an average frequency of 90 beats per minute (Supplementary Figure 1D, Video 4). The microelectrode array technology detected robust and regular baseline beating signals (Supplementary Figure 1E and F), with the detailed parameters outlined in Table 1. To further authenticate the differentiated CMs, immunofluorescence detection was conducted using specific CM makers, including cTNT, NK2 homeobox 5, and 2v isoform of myosin light chain. The cells showed positive staining for all three markers (Supplementary Figure 2A-C). These results confirmed the successful differentiation of hiPSCs into CMs with functional attributes.

| Beat period (s) | FPD (ms) | FPDc (Fridericia ms) | Spike amplitude (mV) | |

| HiPSC-CMs | 1.6 ± 0.0 | 539 ± 59 | 460 ± 52 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

Exos were isolated from the culture media of hiPSCs and hiPSC-CMs. Utilizing nanoparticle tracking analysis analysis, we discovered that the exos derived from hiPSCs (hiPSC-exo) had an average diameter of approximately 165 nm. By contrast, hiPSC-CM-exo had an average diameter of approximately 108 nm (Figure 1A and B). Further examination by transmission electron microscopy substantiated the presence of characteristic bilayered membranes within these isolated exos, confirming their structural integrity (Figure 1C and D). The quantity of these exos/microvesicles was determined using the Bradford assay - a reputable and widely adopted method for protein quantification. Western blot analysis was employed to assess the presence of specific exo markers. Our results confirmed the expression of CD63 and TSG101 in both hiPSC-exos and hiPSC-CM-exos (Figure 1E). This molecular characterization is crucial for verifying the identity and potential functionality of these exos in subsequent therapeutic applications.

We evaluated the protective effects of iPSCs, hiPSC-CMs, hiPSC-exo, and hiPSC-CM-exo on cardiac function following MI in rats. MI was surgically induced by occluding the distal left anterior descending coronary artery (Figure 2A and B). Of 54 rats that underwent the procedure, 50 survived and were evenly divided into five groups. The rats in the iPSC group were injected with 0.5 million hiPSCs, whereas those in the hiPSC-CMs group were injected with 0.5 million hiPSC-CMs at four sites surrounding the MI area in the rats. The iPSC-exo group and hiPSC-CMs-exo group were injected with 40 μg exos derived from hiPSCs and hiPSC-CMs, respectively. By contrast, the PBS group was injected with PBS only. To assess the retention of cells post-injection, luciferase activity was measured on days 0, 3, and 7 following MI. The bioluminescence signal was most intense on day 0, diminished by day 3, and was nearly undetectable by day 7 post-MI (Figure 2C). Cardiac function was evaluated using M-mode echocardiography at four distinct time points: 3, 7, 14, and 28 days post-MI. LVEF and LVFS were notably enhanced in the animals treated with hiPSC-CMs-exo compared to those that received PBS alone, particularly at the 4-week mark. Furthermore, the hiPSC-CMs-exo group demonstrated a significant improvement in LVEF and LVFS when juxtaposed with the iPSC-exo group and iPSC group in week 4 (Figure 2D-F). The hiPSC-CM-exo exhibited a trend toward a more pronounced amelioration of cardiac function compared to the other treatment groups, suggesting the potential therapeutic superiority of hiPSC-CM-exo in the context of myocardial repair.

Next, we performed 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazoliumchloride staining to evaluate the myocardial infarct size 28 days after MI. The results showed that treatment with hiPSC-CM-exo significantly reduced the infarct size, indicating that these exos have the potential to alleviate cardiac damage post-MI (Figure 3). In alignment with the reduction in infarction area, Masson staining of the infarct site at the 4-week post-MI disclosed that the administration of hiPSC-CM-exo resulted in a markedly diminished level of fibrosis when compared to the other treatment groups (Figure 4). These results underscore the therapeutic impact of hiPSC-CM-exos in attenuating the fibrotic consequences of MI.

In delving into the mechanisms behind the improved cardiac function with hiPSC-CM-exo treatment, we hypothesized that the mechanism might encompass the activation of cytoprotective pathways. To test this hypothesis, we quantified apoptotic cells in the hearts of animals euthanized 3 days post-MI (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 3). At the border zone of the infarction, a significantly reduced number of apoptotic cells, identified by TUNEL staining, were observed in the hiPSC-CM-exo group compared to other groups. This finding suggests that hiPSC-CM-exo may possess the capacity to suppress apoptosis induced by MI.

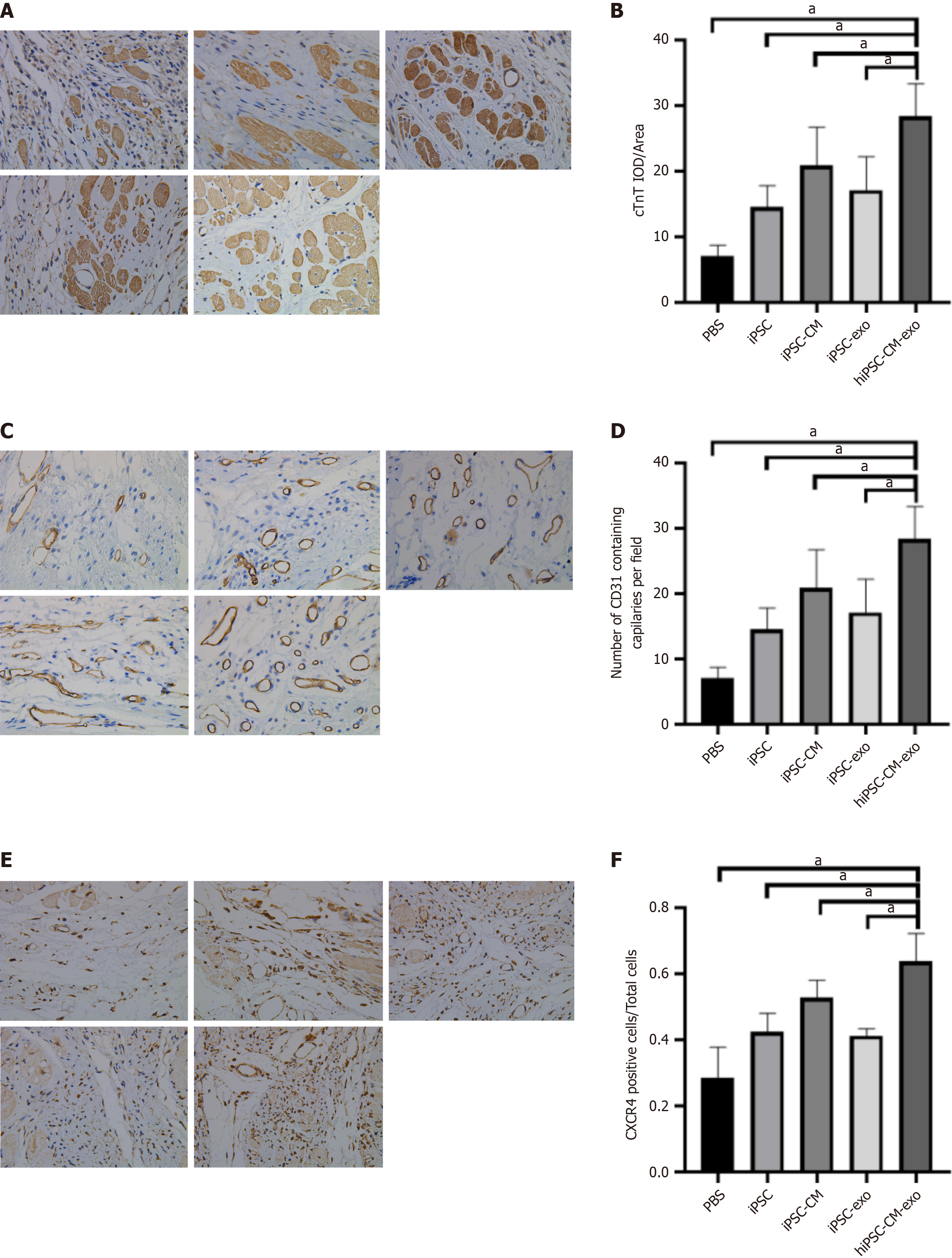

Four weeks after MI, we conducted immunohistochemistry analyses to evaluate the expression levels of cTNT, CD31, and C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4). These markers are indicative of myocardial cell survival, angiogenesis[28,29], and cell migration[30], respectively. The group treated with hiPSC-CM-exo exhibited higher levels of cTNT, CD31, and CXCR4 compared to the other groups, with the most pronounced difference observed between the PBS and hiPSC-CM-exo groups (Figure 6). These results support the hypothesis that exos derived from hiPSC-CMs can enhance CM survival, stimulate angiogenesis, and promote cell migration. The results indicated that the transplantation of hiPSC-CM-exo may trigger paracrine mechanisms that encourage blood vessel growth, cell migration, survival, and intracellular communication, thereby contributing to the repair and regeneration of the heart tissue post-MI.

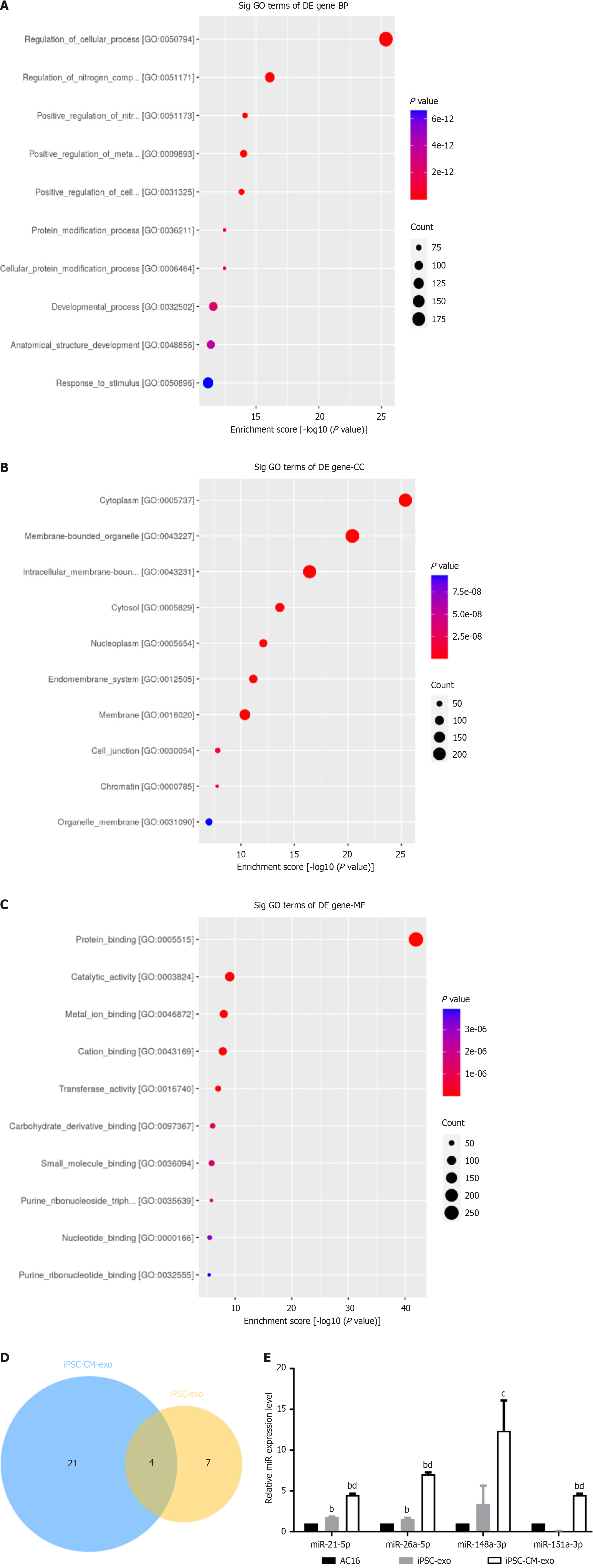

Screening for miRNAs with significantly increased expression levels in iPSC-exo compared to hiPSC-CM-exo, enrichment of target gene Gene Ontology (GO), and annotation of the possible pathways by which miRNAs with high iPSC-exo exert their effects in cells. The enrichment result of biological processes (BP) is GO:0050794 regulation of cellular processes; GO:0051171 regulation of nitrogen compound metabolic process; GO:0051173 Positive regulation of nitrogen compound metabolic process (Figure 7A). The enrichment results of cellular components are GO:0005737 cytoplasm, GO:0043227 membrane-bound organelle, and GO:0043231 intracellular membrane-bound organelle (Figure 7B). The molecular function enrichment results (as shown in Figure 7C) are GO:0005515 protein binding, GO:0003824 catalytic activity, and GO:0046872 metal ion binding. Four miRNAs, hsa-miR-148a-3p, hsa-miR-21-5p, hsa-miR-151a-3p, and hsa-miR-26a-5p, were obtained from the collection of highly expressed miRNAs in hiPSC-CMs-exo and iPSC-exo (Figure 7D). Additional, extract miRNAs from iPSCs-exo, hiPSC-CM-exo, and AC16, real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) showed that the miR-21-5p, miR-151a-3p, miR-26-5p, and miR-148a-3p were highly expressed in iPSCs-exo and hiPSC-CM-exo (Figure 7E).

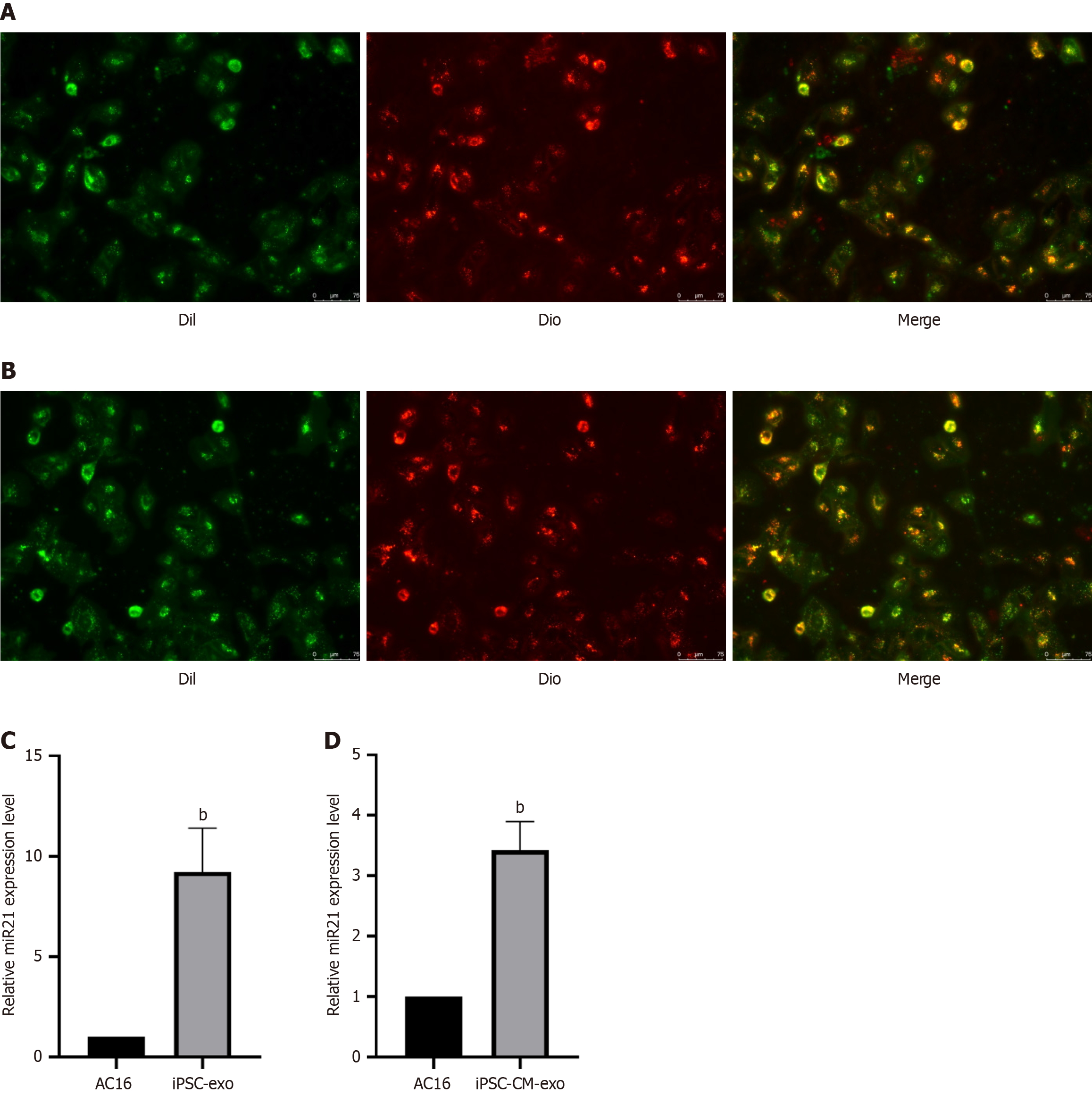

To visually observe whether the miR-21-5p-expressing exos can be absorbed by AC16 cells, we stained the AC16 cell membrane green (Dil) and labeled the extracellular vesicles red (Dio) with membrane dye. After co-culture of AC16 cells with extracellular vesicles, we found that the extracellular vesicles colocalized with AC16 cells (Figure 8A and B), indicating that the extracellular vesicles expressing miR-21-5p could be effectively absorbed by AC16 cells. Next, the expression of miR-21-5p in AC16 cells treated with extracellular vesicles was determined by RT-qPCR. Compared with the untreated group, hiPSC-exo and hiPSC-CM-exo treatments significantly increased the expression of miR-21-5p in AC16 cells (Figure 8C and D).

After treating AC16 cells with 125, 250, and 500 μM CoCl2 for 24 hours, the results of the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay showed that the viability of AC16 cells treated with 500 μM CoCl2 for 24 hours decreased to about 50% (Supplementary Figure 4A). Western blot analysis and RT-qPCR results showed that the expression levels of HIF-1α protein and RNA were significantly increased in AC16 cells treated with 500 μM CoCl2 for 24 hours (Supplementary Figures 4B and C), indicating that chemical hypoxia model of AC16 cells could be successfully constructed after treatment with 500 μM CoCl2 for 24 hours and used for follow-up experiments.

To further explore the role of miR-21-5p, we first transfected mimic or inhibitor into AC cells for miR-21-5p overexpression or knockdown. After transfection with the miR-21-5p mimic (mimic-21 group), compared with the normally cultured group (NC group), the miR-21-5p mimic significantly increased the expression of miR-21-5p (Supplementary Figure 5A), indicating that AC16 cells with high expression of miR-21-5p were successfully obtained. After transfection with the miR-21-5p inhibitor (inhibitor-21), compared with the NC group, the miR-21-5p inhibitor significantly reduced the expression of miR-21-5p (Supplementary Figure 5B), indicating that AC16 cells with low expression of miR-21-5p were successfully obtained.

To investigate the role of miR-21-5p in CMs, AC16 cells were transfected with mimic-21 and inhibitor-21. Then hypoxia was treated, and apoptosis was detected by the TUNEL method. The results showed that hypoxia and inhibitor-21 promoted apoptosis of AC16 cells, while the mimic significantly inhibited apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 5C and D). Furthermore, AC16 cells were transfected with mimic-21 and inhibitor-21. Then hypoxia was treated, and apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry. Consistent with the above results, in the hypoxia group compared to the NC group, cells showed a trend towards increased apoptosis, with an overall rate of apoptosis around 50%. Transfection with the mimic-21 could reduce the rate of apoptosis after hypoxia relative to the hypoxia group (Supplementary Figure 6A), while transfection with the inhibitor-21 could increase the rate of apoptosis after hypoxia relative to the hypoxia group (Supplementary Figure 6B).

To further explore the molecular mechanism of miR-21-5p’s influence on CM apoptosis, we examined the effect of miR-21-5p on the expression of apoptosis-related genes. Western blot analysis showed that, compared with the hypoxia group, anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was increased and pro-apoptotic protein Bax expression was decreased in AC16 CMs in the mimic-21 group (Supplementary Figure 6C). Meanwhile, RT-qPCR was used to detect the RNA expression of Bcl-2 and Bax genes in AC16 cells. Relative to the hypoxia group, the mRNA expression of the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 increased, whereas the mRNA expression of the pro-apoptotic gene Bax decreased in the mimic-21 group (Supplementary Figure 6D). This indicates that transfection with mimic-21 can regulate apoptosis-related genes to promote anti-apoptosis. Furthermore, we examined the effect of miR-21-5p knockdown on apoptosis-related gene expression. Western blotting showed that, compared with the hypoxia group, the levels of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 decreased and pro-apoptotic protein Bax increased in AC16 cells after transfection with inhibitor-21 (Supplementary Figure 6E). RT-qPCR was used to detect the RNA expression of Bcl-2 and Bax genes in AC16 cells. In cells in the inhibitor-21 group, relative to the hypoxia group, the expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 gene was decreased and the expression of the pro-apoptotic Bax gene was increased (Supplementary Figure 6F). This suggests that transfection with the miR-21-5p inhibitor can regulate apoptosis-related genes to promote apoptosis.

The ongoing quest to treat heart disease has been marked by a significant shift towards regenerative medicine, with human pluripotent SCs emerging as a beacon of hope due to their unique properties of self-renewal and differentiation into CMs. The results of this study revealed that hiPSC-CM-exo significantly enhanced LVEF and LVFS in a murine MI model, indicative of improved cardiac function. This improvement was associated with a reduction in infarct size and myocardial fibrosis, suggesting a protective role of hiPSC-CM-exo in mitigating cardiac damage following MI. Fur

Although iPSCs, hiPSC-CMs, and exos have been utilized for cardiac repair, each possesses distinct advantages and disadvantages[31-34]. For the first time, we directly compared the cardiac reparative efficacy of iPSC-exos and hiPSC-CM-exos with that of iPSC and hiPSC-CM in vivo MI models. Our study results demonstrate the successful differentiation of hiPSC into hiPSC-CMs in vitro. The intensity of the cell imaging signal was positively correlated with cell number, enabling the tracking of cell survival in animals. exos secreted by hiPSC-CMs exhibited superior myocardial ischemia repair capabilities compared with hiPSC-CMs, iPSC, and iPSC exos through the promotion of angiogenesis and cell migration, anti-apoptosis, and the reduction of fibrosis. Consequently, exos derived from hiPSC-derived cardiac cells enhanced myocardial recovery, and thus may serve as a potential acellular therapeutic option for myocardial injury.

Many functional effects exerted by exos are mediated by exosomal miRNAs that are specific to the exos’ cells of origin, although several miRNAs appear to be beneficial for myocardial recovery after MI[35]. As exos carry cargo representative of their origin cells, careful selection of the cell type is crucial when determining the therapeutic potential of secreted exos. HiPSC-CM exos effectively affect an injured heart through more CM-specific pathways, including pathological hypertrophy while being enriched with miRNAs that modulate cardiac-specific processes[35]. In investigating whether the miRNAs are associated with exo-mediated cardio protection, we will perform miRNA array analysis on iPSC-exos and hiPSC-CM-exos.

MiR-21-5p has been widely studied for its involvement in various BP, including cell survival, apoptosis, and angiogenesis[21,36,37] mic on apoptosis and the pro-apoptotic effect of its inhibitor, are in line with previous studies that have reported miR-21-5p as a negative regulator of apoptosis[19,38,39]. We found that the upregulation of miR-21-5p in our study led to an increase in Bcl-2, a known anti-apoptotic protein, and a decrease in Bax, a pro-apoptotic protein, suggesting that miR-21-5p may promote cell survival by shifting the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic factors. Conversely, the knockdown of miR-21-5p resulted in decreased Bcl2 and increased Bax expression, which is consistent with the promotion of apoptosis under hypoxic conditions. This is consistent with the mechanism by which miR-21 inhibits apoptosis found in other cells[40]. Moreover, the cellular response to hypoxia is a complex process that involves multiple signaling pathways, including the HIF pathway[41]. It is plausible that miR-21-5p, through its target genes, may also influence the HIF pathway, which is critical for the adaptation of cells to low oxygen conditions. The activation of HIF can lead to the transcription of genes involved in angiogenesis, metabolism, and cell survival, among other processes[42]. Our study’s observation of increased HIF-1α expression in response to CoCl2 treatment further supports the role of hypoxia in modulating cellular responses and the potential interplay between miR-21-5p and HIF pathways in the context of apoptosis. These results not only corroborate previous findings on the anti-apoptotic role of miR-21-5p but also highlight the potential therapeutic applications of modulating miR-21-5p levels in the context of ischemic heart disease and other conditions involving hypoxia.

In this study, we screened miR-21-5p as a potential regulator of cardiac function through miRNA sequencing in exos. The Gene Ontology enrichment analysis showed that BP such as regulation of cellular processes and nitrogen compound metabolic process, aligns with the known roles of miR-21-5p in modulating cellular responses to stress and its potential involvement in metabolic pathways[43]. The experimental validation conducted in this study, which includes the use of mimics and inhibitors to modulate miR-21-5p expression, has provided direct evidence for its role in regulating apoptosis-related genes such as Bcl-2 and Bax. The overexpression of miR-21-5p leading to decreased apoptosis and the knockdown resulting in increased apoptosis are consistent with the bioinformatics analysis that suggests miR-21-5p targets genes involved in cell survival and death. The combination of bioinformatics and experimental validation strengthens the causal relationship between miR-21-5p and the observed phenotype and is critical for understanding the complex regulatory network in which miR-21-5p operates and its role in regulating myocardial stress response.

Recent literature emphasizes the multifaceted role of miR-21-5p in cardiovascular health[39]. Its expression is linked to various cellular processes, including apoptosis, proliferation, and angiogenesis. One potential mechanism by which miR-21-5p exerts cardioprotective effects involves the regulation of the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)/Akt signaling pathway[44,45]. Inhibition of PTEN leads to increased Akt phosphorylation, promoting CM survival and anti-apoptotic signaling. Additionally, miR-21-5p/PTEN/Akt axis can enhance angiogenesis by regulating factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor[44,46]. Vascular endothelial growth factor is crucial for new vessel formation and tissue repair after ischemic injury. The involvement of the HIF pathway discussed in this study further highlights the potential of miR-21-5p to mediate hypoxic responses. This indicates that miR-21-5p plays a broader role in cardiac adaptation and recovery under stress conditions.

The differential effects observed between exos derived from hiPSC-CMs and those from iPSCs stem from their unique characteristics. Exos from different cell types exhibit distinct membrane compositions, surface markers, and cargo profiles[47-50]. HiPSC-CM-exos are specifically tailored for cardiac tissue. They preferentially interact with myocardial cells. This enhances their ability to promote angiogenesis and regulate apoptosis. In contrast, iPSC-exos may not possess these specialized attributes. As a result, they exhibit less effective therapeutic benefits in cardiac repair.

While our study provides compelling evidence for the therapeutic potential of hiPSC-CM-exos, particularly high

Exos from hiPSC-CMs, enriched with miR-21-5p, demonstrated superior therapeutic efficacy over hiPSC-CM cell therapy by improving ejection fraction, reducing fibrosis, and preventing apoptosis, while their low immunogenicity and stability position them as promising candidates for off-the-shelf regenerative therapies.

| 1. | Liu X, Wang L, Wang Y, Qiao X, Chen N, Liu F, Zhou X, Wang H, Shen H. Myocardial infarction complexity: A multi-omics approach. Clin Chim Acta. 2024;552:117680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cho S, Discher DE, Leong KW, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Wu JC. Challenges and opportunities for the next generation of cardiovascular tissue engineering. Nat Methods. 2022;19:1064-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yan W, Xia Y, Zhao H, Xu X, Ma X, Tao L. Stem cell-based therapy in cardiac repair after myocardial infarction: Promise, challenges, and future directions. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2024;188:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sayed N, Liu C, Wu JC. Translation of Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: From Clinical Trial in a Dish to Precision Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2161-2176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Higuchi T, Miyagawa S, Pearson JT, Fukushima S, Saito A, Tsuchimochi H, Sonobe T, Fujii Y, Yagi N, Astolfo A, Shirai M, Sawa Y. Functional and Electrical Integration of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes in a Myocardial Infarction Rat Heart. Cell Transplant. 2015;24:2479-2489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kawamura M, Miyagawa S, Miki K, Saito A, Fukushima S, Higuchi T, Kawamura T, Kuratani T, Daimon T, Shimizu T, Okano T, Sawa Y. Feasibility, safety, and therapeutic efficacy of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte sheets in a porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy model. Circulation. 2012;126:S29-S37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ye L, Chang YH, Xiong Q, Zhang P, Zhang L, Somasundaram P, Lepley M, Swingen C, Su L, Wendel JS, Guo J, Jang A, Rosenbush D, Greder L, Dutton JR, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Kaufman DS, Ge Y, Zhang J. Cardiac repair in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction with human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiovascular cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:750-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shiba Y, Gomibuchi T, Seto T, Wada Y, Ichimura H, Tanaka Y, Ogasawara T, Okada K, Shiba N, Sakamoto K, Ido D, Shiina T, Ohkura M, Nakai J, Uno N, Kazuki Y, Oshimura M, Minami I, Ikeda U. Allogeneic transplantation of iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerates primate hearts. Nature. 2016;538:388-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 65.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tachibana A, Santoso MR, Mahmoudi M, Shukla P, Wang L, Bennett M, Goldstone AB, Wang M, Fukushi M, Ebert AD, Woo YJ, Rulifson E, Yang PC. Paracrine Effects of the Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiac Myocytes Salvage the Injured Myocardium. Circ Res. 2017;121:e22-e36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ong SG, Huber BC, Lee WH, Kodo K, Ebert AD, Ma Y, Nguyen PK, Diecke S, Chen WY, Wu JC. Microfluidic Single-Cell Analysis of Transplanted Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2015;132:762-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim PJ, Mahmoudi M, Ge X, Matsuura Y, Toma I, Metzler S, Kooreman NG, Ramunas J, Holbrook C, McConnell MV, Blau H, Harnish P, Rulifson E, Yang PC. Direct evaluation of myocardial viability and stem cell engraftment demonstrates salvage of the injured myocardium. Circ Res. 2015;116:e40-e50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3378] [Cited by in RCA: 3537] [Article Influence: 321.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhu LP, Tian T, Wang JY, He JN, Chen T, Pan M, Xu L, Zhang HX, Qiu XT, Li CC, Wang KK, Shen H, Zhang GG, Bai YP. Hypoxia-elicited mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes facilitates cardiac repair through miR-125b-mediated prevention of cell death in myocardial infarction. Theranostics. 2018;8:6163-6177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 57.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8246] [Cited by in RCA: 9764] [Article Influence: 542.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sun J, Shen H, Shao L, Teng X, Chen Y, Liu X, Yang Z, Shen Z. HIF-1α overexpression in mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes mediates cardioprotection in myocardial infarction by enhanced angiogenesis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vandergriff A, Huang K, Shen D, Hu S, Hensley MT, Caranasos TG, Qian L, Cheng K. Targeting regenerative exosomes to myocardial infarction using cardiac homing peptide. Theranostics. 2018;8:1869-1878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hänninen M, Jäntti T, Tolppanen H, Segersvärd H, Tarvasmäki T, Lassus J, Vausort M, Devaux Y, Sionis A, Tikkanen I, Harjola VP, Lakkisto P; For The CardShock Study Group. Association of miR-21-5p, miR-122-5p, and miR-320a-3p with 90-Day Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mi XL, Gao YP, Hao DJ, Zhang ZJ, Xu Z, Li T, Li XW. Prognostic value of circulating microRNA-21-5p and microRNA-126 in patients with acute myocardial infarction and infarct-related artery total occlusion. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:947721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Raupach A, Torregroza C, Niestegge J, Feige K, Klemm-Meyer S, Bauer I, Brandenburger T, Grievink H, Heinen A, Huhn R. MiR-21-5p but not miR-1-3p expression is modulated by preconditioning in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47:6669-6677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang J, Lu Y, Mao Y, Yu Y, Wu T, Zhao W, Zhu Y, Zhao P, Zhang F. IFN-γ enhances the efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes via miR-21 in myocardial infarction rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li Y, Chen X, Jin R, Chen L, Dang M, Cao H, Dong Y, Cai B, Bai G, Gooding JJ, Liu S, Zou D, Zhang Z, Yang C. Injectable hydrogel with MSNs/microRNA-21-5p delivery enables both immunomodification and enhanced angiogenesis for myocardial infarction therapy in pigs. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabd6740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Bao X, Hsiao C, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:162-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 990] [Cited by in RCA: 1263] [Article Influence: 97.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tang J, Shen D, Caranasos TG, Wang Z, Vandergriff AC, Allen TA, Hensley MT, Dinh PU, Cores J, Li TS, Zhang J, Kan Q, Cheng K. Therapeutic microparticles functionalized with biomimetic cardiac stem cell membranes and secretome. Nat Commun. 2017;8:13724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tang J, Su T, Huang K, Dinh PU, Wang Z, Vandergriff A, Hensley MT, Cores J, Allen T, Li T, Sproul E, Mihalko E, Lobo LJ, Ruterbories L, Lynch A, Brown A, Caranasos TG, Shen D, Stouffer GA, Gu Z, Zhang J, Cheng K. Targeted repair of heart injury by stem cells fused with platelet nanovesicles. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2:17-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tang J, Cui X, Caranasos TG, Hensley MT, Vandergriff AC, Hartanto Y, Shen D, Zhang H, Zhang J, Cheng K. Heart Repair Using Nanogel-Encapsulated Human Cardiac Stem Cells in Mice and Pigs with Myocardial Infarction. ACS Nano. 2017;11:9738-9749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Luo L, Tang J, Nishi K, Yan C, Dinh PU, Cores J, Kudo T, Zhang J, Li TS, Cheng K. Fabrication of Synthetic Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Mice. Circ Res. 2017;120:1768-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sahn DJ, DeMaria A, Kisslo J, Weyman A. Recommendations regarding quantitation in M-mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic measurements. Circulation. 1978;58:1072-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5281] [Cited by in RCA: 5466] [Article Influence: 116.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Majchrzak K, Kaspera W, Szymaś J, Bobek-Billewicz B, Hebda A, Majchrzak H. Markers of angiogenesis (CD31, CD34, rCBV) and their prognostic value in low-grade gliomas. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2013;47:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang D, Stockard CR, Harkins L, Lott P, Salih C, Yuan K, Buchsbaum D, Hashim A, Zayzafoon M, Hardy RW, Hameed O, Grizzle W, Siegal GP. Immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of neovascularization in tumor xenografts. Biotech Histochem. 2008;83:179-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hu X, Dai S, Wu WJ, Tan W, Zhu X, Mu J, Guo Y, Bolli R, Rokosh G. Stromal cell derived factor-1 alpha confers protection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: role of the cardiac stromal cell derived factor-1 alpha CXCR4 axis. Circulation. 2007;116:654-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Adamiak M, Cheng G, Bobis-Wozowicz S, Zhao L, Kedracka-Krok S, Samanta A, Karnas E, Xuan YT, Skupien-Rabian B, Chen X, Jankowska U, Girgis M, Sekula M, Davani A, Lasota S, Vincent RJ, Sarna M, Newell KL, Wang OL, Dudley N, Madeja Z, Dawn B, Zuba-Surma EK. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Safer and More Effective for Cardiac Repair Than iPSCs. Circ Res. 2018;122:296-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gallet R, Dawkins J, Valle J, Simsolo E, de Couto G, Middleton R, Tseliou E, Luthringer D, Kreke M, Smith RR, Marbán L, Ghaleh B, Marbán E. Exosomes secreted by cardiosphere-derived cells reduce scarring, attenuate adverse remodelling, and improve function in acute and chronic porcine myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:201-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sanganalmath SK, Bolli R. Cell therapy for heart failure: a comprehensive overview of experimental and clinical studies, current challenges, and future directions. Circ Res. 2013;113:810-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jiang X, Yang Z, Dong M. Cardiac repair in a murine model of myocardial infarction with human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gabisonia K, Prosdocimo G, Aquaro GD, Carlucci L, Zentilin L, Secco I, Ali H, Braga L, Gorgodze N, Bernini F, Burchielli S, Collesi C, Zandonà L, Sinagra G, Piacenti M, Zacchigna S, Bussani R, Recchia FA, Giacca M. MicroRNA therapy stimulates uncontrolled cardiac repair after myocardial infarction in pigs. Nature. 2019;569:418-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cong M, Shen M, Wu X, Li Y, Wang L, He Q, Shi H, Ding F. Improvement of sensory neuron growth and survival via negatively regulating PTEN by miR-21-5p-contained small extracellular vesicles from skin precursor-derived Schwann cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang J, Wang J, Wang Y, Ma R, Zhang S, Zheng J, Xue W, Ding X. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived miR-21-5p Protects Grafted Islets Against Apoptosis by Targeting PDCD4. Stem Cells. 2023;41:169-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Cheng Y, Zhu P, Yang J, Liu X, Dong S, Wang X, Chun B, Zhuang J, Zhang C. Ischaemic preconditioning-regulated miR-21 protects heart against ischaemia/reperfusion injury via anti-apoptosis through its target PDCD4. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:431-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Qiao L, Hu S, Liu S, Zhang H, Ma H, Huang K, Li Z, Su T, Vandergriff A, Tang J, Allen T, Dinh PU, Cores J, Yin Q, Li Y, Cheng K. microRNA-21-5p dysregulation in exosomes derived from heart failure patients impairs regenerative potential. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:2237-2250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Gao X, Huang X, Yang Q, Zhang S, Yan Z, Luo R, Wang P, Wang W, Xie K, Gun S. MicroRNA-21-5p targets PDCD4 to modulate apoptosis and inflammatory response to Clostridium perfringens beta2 toxin infection in IPEC-J2 cells. Dev Comp Immunol. 2021;114:103849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell. 2012;148:399-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2389] [Cited by in RCA: 2491] [Article Influence: 191.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4764] [Cited by in RCA: 5012] [Article Influence: 227.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Moghaddam AS, Afshari JT, Esmaeili SA, Saburi E, Joneidi Z, Momtazi-Borojeni AA. Cardioprotective microRNAs: Lessons from stem cell-derived exosomal microRNAs to treat cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2019;285:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Gao X, Xiong Y, Li Q, Han M, Shan D, Yang G, Zhang S, Xin D, Zhao R, Wang Z, Xue H, Li G. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of miR-21-5p from mesenchymal stromal cells to neurons alleviates early brain injury to improve cognitive function via the PTEN/Akt pathway after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Liu HY, Zhang YY, Zhu BL, Feng FZ, Yan H, Zhang HY, Zhou B. miR-21 regulates the proliferation and apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells through PTEN/PI3K/AKT. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:4149-4155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Akt takes center stage in angiogenesis signaling. Circ Res. 2000;86:4-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Li M, Li S, Du C, Zhang Y, Li Y, Chu L, Han X, Galons H, Zhang Y, Sun H, Yu P. Exosomes from different cells: Characteristics, modifications, and therapeutic applications. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;207:112784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Zhang M, Hu S, Liu L, Dang P, Liu Y, Sun Z, Qiao B, Wang C. Engineered exosomes from different sources for cancer-targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Phan J, Kumar P, Hao D, Gao K, Farmer D, Wang A. Engineering mesenchymal stem cells to improve their exosome efficacy and yield for cell-free therapy. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7:1522236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zhu X, Badawi M, Pomeroy S, Sutaria DS, Xie Z, Baek A, Jiang J, Elgamal OA, Mo X, Perle K, Chalmers J, Schmittgen TD, Phelps MA. Comprehensive toxicity and immunogenicity studies reveal minimal effects in mice following sustained dosing of extracellular vesicles derived from HEK293T cells. J Extracell Vesicles. 2017;6:1324730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |