Published online Apr 26, 2022. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v14.i4.314

Peer-review started: December 12, 2021

First decision: January 12, 2022

Revised: January 21, 2022

Accepted: March 16, 2022

Article in press: March 16, 2022

Published online: April 26, 2022

Processing time: 135 Days and 1.9 Hours

The original study by Alessio et al reported that skinny people (SP) serum can promote the formation of brown adipocytes, but not the differentiation of white adipocytes. This finding may explain why SP do not often become obese, despite consuming more calories than the body needs. More importantly, they demonstrated that circulating factors in SP serum can promote the expression of UCP-1 protein, thereby reducing fat accumulation. In this study, only male serum samples were evaluated to avoid the interference of sex hormones in experiments, but adult males also synthesize estrogen, which is produced by the cells of the testes. At the same time, adult females secrete androgens, and females synthesize androgens that are mainly produced by the adrenal cortex. We believe that the approach of excluding sex hormone interference by sex selection alone may be flawed, so we comment on the article and debate the statistical analysis of the article.

Core Tip: Both men and women secrete estrogens and androgens. In females, androgens are mainly derived from the sites of the zona fasciculata and the zona reticularis in the adrenal cortex. In males, estrogens are produced by surrounding tissues, such as the skin, through the conversion of testosterone. Sex hormones in the serum can affect the differentiation and the stereotype of multipotent stem cells.

- Citation: Gu YL, Shen W, Li ZP, Zhou B, Lin ZJ, He LP. Skinny people serum factors promote the differentiation of multipotent stem cells into brown adipose tissue. World J Stem Cells 2022; 14(4): 314-317

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v14/i4/314.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v14.i4.314

We have read with great interest the ingenious article written by Alessio et al[1] published in World Journal of Stem Cells. Their valuable research explains why skinny people (SP) ingest more calories than the body needs while presenting normal body composition. They reasoned that the existence of certain factors in the serum of SP can promote the differentiation of multipotent stem cells (MSCs) towards brown adipocytes. After reading the article, we agreed that several issues are worthy of discussion. Here, we state our views and contribute to the debate.

Studies have shown that sex hormones, including estrogens and androgens, can affect the differentiation and commitment of MSCs[2]. In a previous study, Alrabadi[3] reported that androgen injections could increase aggressiveness, as well as the body weight of rats, indicative of an association between aggressiveness and body weight. Serum androgen levels in men are usually higher than those in women due to testosterone secretion by the cells of the testes. Androgens can affect body weight by affecting MSCs, and testosterone (a type of androgen) can induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy through a variety of mechanisms. For instance, testosterone can regulate the commitment and differentiation of MSCs. Furthermore, testosterone increases lean body mass and reduces fat mass in young men, and the magnitude of these changes is significantly correlated with testosterone concentration[4]. Therefore, we suggest that the interference of androgen itself on MSC commitment and differentiation should be excluded as much as possible when studying cytokine stimulators of MSCs in the sera of adult males.

In men, estrogen exists in the plasma in a form with high biological activity, estradiol. Approximately 15% of the circulating estrogens are derived directly from the cells of the testes, and the remaining estradiol is derived from aromatase catalysis in peripheral tissues[5,6]. Adult males secrete approximately 30-40 micrograms of estradiol per day, and accumulating evidence supports the key roles of this hormone in the regulation of male metabolism. In men, estradiol may be a stronger influencing factor of obesity than testosterone, and even short-term estradiol deprivation can lead to increased fat mass[4,6]. Therefore, it is not ideal to eliminate the influence of sex hormones through gender selection, and we recommend that the authors expand the study by isolating and eliminating the interfering effects of sex hormones.

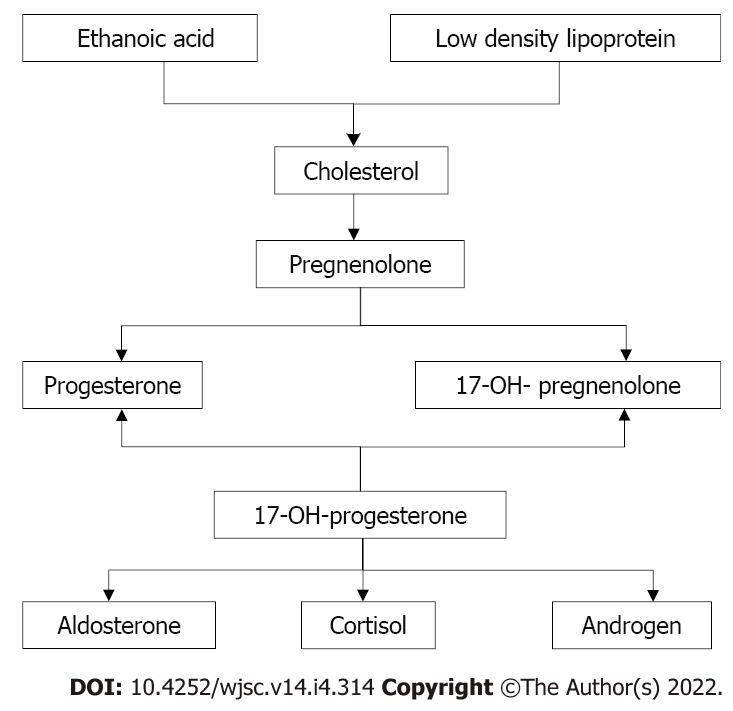

In the context of the global pandemic, there are no gender differences in overweight and obesity in most regions, except for a few developing areas with gender or ethnic differences[7,8]. We suggest that the authors expand the female sample size and consider the following factors. Androgen synthesis also occurs in women, and androgens are synthesized by the adrenal cortex and ovary. The adrenal cortex is a major contributor of androgen synthesis in women (Figure 1), and the sites of androgen synthesis are the zona fasciculata and the zona reticularis in the adrenal cortex. The adrenal cortex’s ability to secrete androgens is maintained throughout life, with the organ mainly synthesizing dehydroepiandrosterone and androstenedione. Although their biological activity is weak, these hormones are converted into more active forms, where they function in the peripheral blood. More importantly, the active forms of androgens synthesized by the adrenal glands affect MSC commitment and differentiation, which in turn affects body weight and fat metabolism[9-11].

The study stated that serum samples were collected from 12 adult men with a normal body mass index. The author divided these men into two groups, namely, the SP group and the normal people (NP) group, with six samples in each group. Although the author stated that the daily calorie intake of the SP group exceeded 30%-40% of the body calorie requirement, we recommend that the author provide additional details on the individual diets.

Using the author’s data, we employed Power and Sample Size Calculation software (HyLown Consulting LLC Atlanta, GA, United States) for sample size estimation. We estimated the sample size of triglycerides to a type II error β of 0.2, that is, a power of 0.8 (1-β) and a first type error (α) of 5%. According to the data in Table 1, which reported the clinical parameters, the mean concentrations of triglycerides in NP and SP groups were 79.2 mmol/L and 98.1 mmol/L, respectively, the sample ratio was 1, and the standard deviation(σ) was 22. According to our calculation, the theoretical conservative estimate of the sample size of each group should be at least 22 cases, while the sample size of each group in this study was only 6 cases. Thus, we believe that the statistical power of this study was low, and we suggest that the author expand the study by increasing the sample size.

| NP | SP | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.10 ± 1.10 | 20.50 ± 1.30 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 84.8 ± 6.20 | 87.0 ± 5.80 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 190.6 ± 23.18 | 185.6 ± 20.12 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 127.2 ± 21.10 | 130.6 ± 25.27 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 59.3 ± 8.80 | 62.6 ± 12.14 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 79.2 ± 22.40 | 98.1 ± 46.42 |

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Biochemistry and molecular biology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Gallone A, Italy; Prasetyo EP, Indonesia; Sallustio F, Italy; Silva-Junior AJD, Brazil; Ventura C, Italy S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Alessio N, Squillaro T, Monda V, Peluso G, Monda M, Melone MA, Galderisi U, Di Bernardo G. Circulating factors present in the sera of naturally skinny people may influence cell commitment and adipocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells. World J Stem Cells. 2019;11:180-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Hong L, Sultana H, Paulius K, Zhang G. Steroid regulation of proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells: a gender difference. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;114:180-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alrabadi N, Al-Rabadi GJ, Maraqa R, Sarayrah H, Alzoubi KH, Alqudah M, Al-U'datt DG. Androgen effect on body weight and behaviour of male and female rats: novel insight on the clinical value. Andrologia. 2020;52:e13730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Herbst KL, Bhasin S. Testosterone action on skeletal muscle. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:271-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nelson LR, Bulun SE. Estrogen production and action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:S116-S124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rubinow KB. Estrogens and Body Weight Regulation in Men. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1043:285-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | An R, Shen J, Bullard T, Han Y, Qiu D, Wang S. A scoping review on economic globalization in relation to the obesity epidemic. Obes Rev. 2020;21:e12969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chang E, Varghese M, Singer K. Gender and Sex Differences in Adipose Tissue. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mauvais-Jarvis F, Clegg DJ, Hevener AL. The role of estrogens in control of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Endocr Rev. 2013;34:309-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 918] [Article Influence: 76.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Takao K, Iizuka K, Liu Y, Sakurai T, Kubota S, Kubota-Okamoto S, Imaizumi T, Takahashi Y, Rakhat Y, Komori S, Hirose T, Nonomura K, Kato T, Mizuno M, Suwa T, Horikawa Y, Sone M, Yabe D. Effects of ChREBP deficiency on adrenal lipogenesis and steroidogenesis. J Endocrinol. 2021;248:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schnabl K, Westermeier J, Li Y, Klingenspor M. Opposing Actions of Adrenocorticotropic Hormone and Glucocorticoids on UCP1-Mediated Respiration in Brown Adipocytes. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |