Published online Nov 26, 2020. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i11.1410

Peer-review started: July 10, 2020

First decision: August 9, 2020

Revised: August 19, 2020

Accepted: September 25, 2020

Article in press: September 25, 2020

Published online: November 26, 2020

Processing time: 139 Days and 0.8 Hours

Cellular metabolism regulates stemness in health and disease. A reduced redox state is essential for self-renewal of normal and cancer stem cells (CSCs). However, while stem cells rely on glycolysis, different CSCs, including pancreatic CSCs, favor mitochondrial metabolism as their dominant energy-producing pathway. This suggests that powerful antioxidant networks must be in place to detoxify mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and maintain stemness in oxidative CSCs. Since glutathione metabolism is critical for normal stem cell function and CSCs from breast, liver and gastric cancer show increased glutathione content, we hypothesized that pancreatic CSCs also rely on this pathway for ROS detoxification.

To investigate the role of glutathione metabolism in pancreatic CSCs.

Primary pancreatic cancer cells of patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) were cultured in adherent or CSC-enriching sphere conditions to determine the role of glutathione metabolism in stemness. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to validate RNAseq results involving glutathione metabolism genes in adherent vs spheres, as well as the expression of pluripotency-related genes following treatment. Public TCGA and GTEx RNAseq data from pancreatic cancer vs normal tissue samples were analyzed using the webserver GEPIA2. The glutathione-sensitive fluorescent probe monochlorobimane was used to determine glutathione content by fluorimetry or flow cytometry. Pharmacological inhibitors of glutathione synthesis and recycling [buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO) and 6-Aminonicotinamide (6-AN), respectively] were used to investigate the impact of glutathione depletion on CSC-enriched cultures. Staining with propidium iodide (cell cycle), Annexin-V (apoptosis) and CD133 (CSC content) were determined by flow cytometry. Self-renewal was assessed by sphere formation assay and response to gemcitabine treatment was used as a readout for chemoresistance.

Analysis of our previously published RNAseq dataset E-MTAB-3808 revealed up-regulation of genes involved in the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) Pathway Glutathione Metabolism in CSC-enriched cultures compared to their differentiated counterparts. Consistently, in pancreatic cancer patient samples the expression of most of these up-regulated genes positively correlated with a stemness signature defined by NANOG, KLF4, SOX2 and OCT4 expression (P < 10-5). Moreover, 3 of the upregulated genes (MGST1, GPX8, GCCT) were associated with reduced disease-free survival in patients [Hazard ratio (HR) 2.2-2.5; P = 0.03-0.0054], suggesting a critical role for this pathway in pancreatic cancer progression. CSC-enriched sphere cultures also showed increased expression of different glutathione metabolism-related genes, as well as enhanced glutathione content in its reduced form (GSH). Glutathione depletion with BSO induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in spheres, and diminished the expression of stemness genes. Moreover, treatment with either BSO or the glutathione recycling inhibitor 6-AN inhibited self-renewal and the expression of the CSC marker CD133. GSH content in spheres positively correlated with intrinsic resistance to gemcitabine treatment in different PDXs r = 0.96, P = 5.8 × 1011). Additionally, CD133+ cells accumulated GSH in response to gemcitabine, which was abrogated by BSO treatment (P < 0.05). Combined treatment with BSO and gemcitabine-induced apoptosis in CD133+ cells to levels comparable to CD133- cells and significantly diminished self-renewal (P < 0.05), suggesting that chemoresistance of CSCs is partially dependent on GSH metabolism.

Our data suggest that pancreatic CSCs depend on glutathione metabolism. Pharmacological targeting of this pathway showed that high GSH content is essential to maintain CSC functionality in terms of self-renewal and chemoresistance.

Core Tip: Several glutathione metabolism genes are upregulated in pancreatic cancer stem cells (CSCs), and their expression correlates with a stemness signature and predicts survival in clinical samples. Increased glutathione concentration in CSCs promotes viability, cell cycle progression and pluripotency gene expression. Inhibition of glutathione synthesis or recycling impairs CSC functionalities such as self-renewal and chemoresistance. Our data demonstrate a targetable metabolic vulnerability of this aggressive subpopulation of cancer cells.

- Citation: Jagust P, Alcalá S, Sainz Jr B, Heeschen C, Sancho P. Glutathione metabolism is essential for self-renewal and chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer stem cells. World J Stem Cells 2020; 12(11): 1410-1428

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v12/i11/1410.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v12.i11.1410

Pancreatic cancer has the worst outcome of any cancer in the world, and is currently the 3rd most frequent cause of cancer-related deaths[1]. At the same time, the incidence of pancreatic cancer keeps increasing, with approximately 448000 new cases in 2019. This number is predicted to further increase in the coming years and, due to its extreme lethality and lack of effective treatments available[2], pancreatic cancer may even become the 2nd most frequent cause of cancer-related deaths by 2030[3].

One possible explanation for the poor outcome associated with pancreatic cancer is that, previously, only little attention had been paid to the efficient elimination of cancer stem cells (CSCs). Pancreatic cancer contains stem cell-like cells, which are the sole drivers of tumorigenesis, much like normal stem cells fuel proliferation and differentiation in normal tissue, and therefore have been termed CSCs[4-8]. While CSCs represent only a small fraction of all the cancer cells, they are extremely tumorigenic down to a single cell, and exclusively metastatic[4,6]. Current treatment strategies for pancreatic cancer spare CSCs due to their inherent chemoresistance[8-10] and therefore likely represent the key cellular source driving disease relapse. To develop more effective treatment strategies for pancreatic cancer, we need to obtain a thorough understanding of the regulatory machinery of CSCs, including their cellular metabolism.

Increasing evidence suggests that, similar to normal stem cells, cellular metabolism is highly regulated in CSCs and governs essential aspects of their functionality. Indeed, a reduced intracellular redox state with low reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels allows for self-renewal, while ROS accumulation induces differentiation[11]. Since relatively high amounts of ROS are formed as by-products of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis was traditionally considered the preferred metabolic pathway for both stem cells and CSCs[12]. However, CSCs across a wide range of cancers maintain low ROS levels[13-15], even if they favor mitochondrial metabolism as their dominant energy-producing pathway[16]. In particular, we have shown that pancreatic CSCs are dependent on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation for full stemness and tumorigenicity, in a process controlled by the balanced expression of c-MYC and the mitochondrial biogenesis factor PGC-1α[7]. We observed that pancreatic CSCs bear low levels of mitochondrial ROS and they are especially sensitive to the mitochondrial ROS inducer menadione, making the redox state of this organelle a relevant target for CSC elimination.

Glutathione (L-γ-glutamyl-L-cysteinyl-glycine; GSH) is the most abundant non-protein antioxidant in eukaryotic cells. Although it is synthesized in the cytosol, glutathione levels are particularly high in mitochondria, where it maintains redox balance through ROS detoxification and protects phospholipids in the mitochondrial membrane[17]. Interestingly, glutathione levels are strongly increased in murine embryonic stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells, supporting defense against diverse insults and maintenance of stemness[18]. Similarly, glutathione content and specific GSH-related enzymes are up-regulated in CSCs from breast[13], liver[19] and gastric cancer[14]. Additionally, different components of the glutathione metabolism pathway have been shown to promote tumor initiation[20], metastasis[21,22] and chemoresist-ance[23]; features frequently associated with CSCs.

However, little is known about the role of this pathway in pancreatic CSCs. Here we now show that pancreatic CSCs display increased GSH content and expression of diverse genes involved in the glutathione metabolism pathway, which correlated with stemness and disease-free survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Depletion of GSH levels in sphere cultures with pharmacological inhibitors of glutathione synthesis or recycling induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. This translated into diminished self-renewal capacity and reduced expression of the CSC surface marker CD133. Importantly, GSH depletion sensitized CSCs to gemcitabine, suggesting an important role for glutathione in chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer.

Human pancreatic cancer Patient-Derived Xenografts [PDXs, either pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) or pancreatic cancer of hepatobiliary origin] were obtained through the Biobank of the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), Madrid, Spain (reference 1204090835CHMH). For primary cultures, PDX tissue fragments previously expanded in nude mice (passages 1-13) were minced, enzymatically digested with collagenase (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) for 90 min at 37°C[24], and after centrifugation for 5 min at 1200 rpm the pellets were resuspended and cultured in RPMI, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 50 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. For the experiments, cells were cultured in DMEM:F12 supplemented with B-27, L-Glutamine (all from Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 50 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and β-FGF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA).

Pancreatic cancer spheres were generated and expanded in supplemented DMEM-F12. A total of 104 cells/mL was seeded in ultra-low attachment plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) as described previously[25].

Cells were seeded in triplicate in ultra-low attachment 24-well plates (Corning) at 104 cells/well in supplemented DMEM-F12 with or without the corresponding treatments, which were refreshed every other day. After 7 d, spheres were counted using a microscope at 20× magnification.

Total RNAs from human primary pancreatic cancer cells and spheres were extracted with the TRIzol kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One microgram of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) and random hexamers. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The list of utilized primers is detailed in Table 1.

| Gene | Primer |

| HPRT | |

| Forward | TGACCTTGATTTATTTTGCATACC |

| Reverse | CGAGCAAGACGTTCAGTCCT |

| GCLC | |

| Forward | GCCGCTGAGCTGGGAGGAAA |

| Reverse | ATTCCACCTCATCGCCCCACT |

| GPX1 | |

| Forward | TATCGAGAATGTGGCGTCCC |

| Reverse | GATGCCCAAACTGGTTGCAC |

| GPX2 | |

| Forward | GGACATCAGGAGAACTGTCAGA |

| Reverse | TCAGGTAGGCGAAGACAGGA |

| GGT1 | |

| Forward | CAACCTGCCCACAGTGAAGA |

| Reverse | TTCTTGGCCTCCATGACTGC |

| GGT2 | |

| Forward | CCCTTCTTTCAGTGGGAGGG |

| Reverse | ATGCTGTCACCTTTGTGGCT |

| GSTM1 | |

| Forward | AGGAAAAGAAGTACACGATGGG |

| Reverse | TTGCTCTGGGTGATCTTGTG |

| GSTA1 | |

| Forward | CAACCTGCCCACAGTGAAGA |

| Reverse | TTCTTGGCCTCCATGACTGC |

| GSTA2 | |

| Forward | CCCTTCTTTCAGTGGGAGGG |

| Reverse | ATGCTGTCACCTTTGTGGCT |

| GSTA | |

| Forward | TCCGTGAGATGGGTTTTAGC |

| Reverse | CTGTACCAACTTCATCCCGTC |

| IDH1 | |

| Forward | CAAGTGACGGAACCCAAAAG |

| Reverse | ACCCTTAGACAGAGCCATTTG |

| IDH2 | |

| Forward | ACAACACCGACGAGTCCATC |

| Reverse | GCCCATCGTAGGCTTTCAGT |

The glutathione-sensitive fluorescent probe monochlorobimane (mCLB, Sigma-Aldrich) was used to analyze the reduced intracellular glutathione content. Cells were trypsinized on the day of the experiment, washed, protected from light and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 2 mmol/L mCLB diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Cells were then washed and resuspended in PBS and fluorescence (excitation: 380 nm, emission: 461 nm) was measured on a FLUOstar OPTIMA Microplate Reader. Values were corrected for cell content by measuring the protein concentration of the sample with the Bradford assay. Alternatively, cells were incubated with DAPI and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACS Canto II (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and data were analyzed with FlowJo 9.2 software (Ashland, OR, USA) or Cytobank (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA).

To identify pancreatic CSCs, the anti-CD133/1 (APC or PE, Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) or corresponding control Immunoglobulin G (IgG) 1 antibody were used. Briefly, cells were stained for 30 min on ice with gentle rocking. DAPI was used for exclusion of dead cells (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). All samples were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACS Canto II (BD) and data were analyzed with FlowJo 9.2 software or Cytobank.

Five-day old spheres or adherent cultures were treated for 48 h in the presence of 100 mmol/L buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO) or BSO and gemcitabine (1 μmol/L). Attached and floating cells were collected, resuspended and stained with Annexin V (550474) diluted in Annexin V binding buffer (556454, all from eBiosciences) for 20 min at room temperature, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then incubated with DAPI for an additional 5 min.

Spheres were trypsinized, washed in PBS, centrifuged, and pellets were fixed in 200 µL of 70% ethanol and stored at -20°C until use. The cells were centrifuged and pellets resuspended in 200 µL of PBS, 10 µg/mL of RNAse A was added and the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in propidium iodide solution (0.1% sodium citrate, 0.1% TritonX-100, and 50 µg/mL propidium iodide).

Expression of the genes contained in the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) Pathway Glutathione Metabolism was investigated in our published RNAseq dataset E-MTAB-3808 (Array Express), which compares primary PDX cells cultured either by adherence or as spheres[7]. All original bioinformatic analyses on this dataset E-MTAB-3808 were performed at the Bioinformatics Unit and Structural Biology and Biocomputing Programme, Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), Madrid 28029, Spain. Differential expression of genes across the different conditions was calculated with Cuffdiff[26].

Expression data from pancreatic cancer and normal tissue from the TCGA and the GTEx projects were analyzed using the webserver GEPIA2[27]. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for correlation analysis of glutathione-related genes with a stemness signature defined by the combined expression of the pluripotency-related genes NANOG, KLF4, SOX2 and OCT4. For disease-free survival analysis, the Hazard ratio (HR) was calculated using the Cox Proportional Hazards model for pancreatic cancer patients from upper and lower quartiles of expression of the indicated genes.

Results for continuous variables are presented as mean ± SE unless stated otherwise. Treatment groups were compared with the independent samples t-test. Pair-wise multiple comparisons were performed with the one-way ANOVA (two-sided) with Bonferroni adjustment. Correlation analysis was performed by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Prism GraphPad (version 5.04).

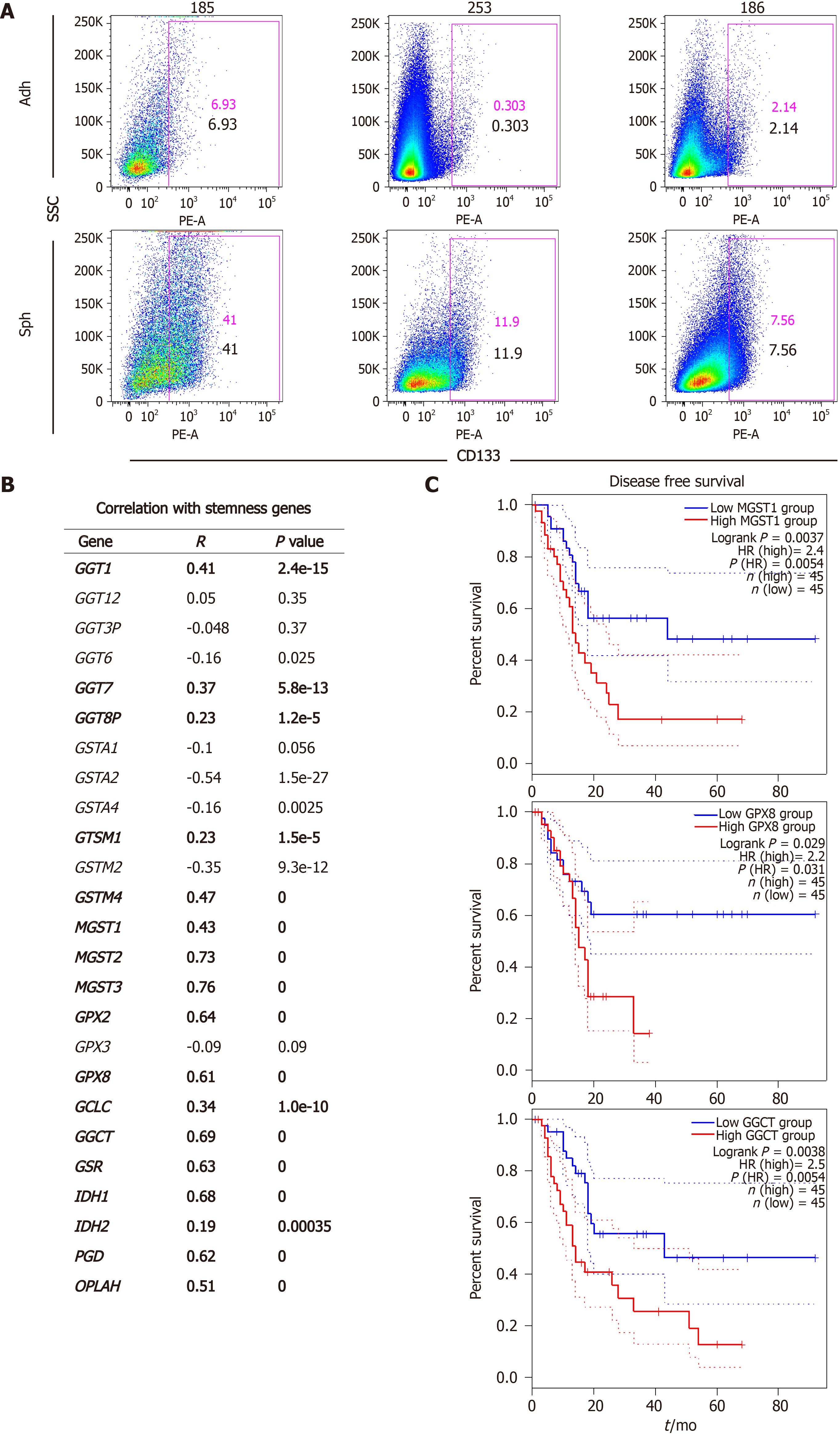

In order to determine a possible connection between glutathione metabolism and stemness in pancreatic cancer, we first analyzed our previously published RNAseq dataset E-MTAB-3808 comparing 5 different PDAC PDX models cultured in differentiating (adherent) or CSC-enriching (spheres) conditions (Figure 1A)[7]. We focused on genes related to the KEGG Pathway Glutathione Metabolism, which we categorized into four different classes: Gamma-glutamyltransferases (GGTs), glutathione-s-transferases (GSTs), glutathione peroxidases (GPXs), and genes involved in glutathione synthesis and recycling. As summarized in Table 2, CSC-enriched cultures generally up-regulated genes from the four classes, although the specific genes varied among the different PDXs.

| PDX | GGTs | GSTs | GPXs | Synthesis and recycling |

| PDX185 | GGT1, GGT2, GGT3P, GGT6, GGT7 | GSTA1, GSTA2, GSTT1, MGST2, MGST3 | GPX2, GPX3 | GCLC, GSR, PGD, IDH1 |

| PDX215 | GGT1, GGT2, GGT7, GGT8P | GSTA1, GSTA4, GSTM2, GSTM4, MGST2 | OPLAH, IDH1 | |

| PDX253 | GGT1, GGT2, GGT3P, GGT6 | GSTA1, GSTA2, GSTA4, MGST1, MGST2, MGST3 | GPX2, GPX8 | GSR, IDH1 |

| PDX354 | GSTA1, GSTA2, MGST1, GSTM2 | GPX3, GPX8 | GCLC, GGCT, IDH1 | |

| PDX265 | GSTA4, GSTM1, GSTM2, GSTM4 | GPX2 | GGCT, PGD, IDH1, IDH2 |

We have previously demonstrated that pancreatic CSCs show increased expression of several pluripotency-related genes such as NANOG, KLF4, SOX2 and OCT4, which we have routinely used as a stemness signature[5-7]. In order to further support a connection between glutathione metabolism and stemness, we used the webserver GEPIA2 to analyze our target genes in human expression data from normal pancreas and PDAC tissues included in the TCGA and GTEx projects. Thus, we performed gene expression correlation studies between the different glutathione-related genes up-regulated in spheres and our defined stemness signature in normal vs PDAC samples. Interestingly, expression of 17 of the 25 genes up-regulated in CSCs positively correlated with the stemness signature in human samples, with P-values below 10-5 (Figure 1B). Since disease recurrence can be mainly attributed to CSCs due to their ability to regenerate tumors following treatment, we next investigated whether the expression of any of the 17 genes correlated with disease-free survival in patients (Figure 1C). We found that high expression of MGST1, GPX8 and GGCT predicted between 2.2-2.5 times increased risk of recurrence in PDAC patients (P = 0.0054, 0.03 and 0.0054, respectively). Together, our results suggest a functional link between glutathione metabolism, stemness and the aggressiveness of pancreatic cancer.

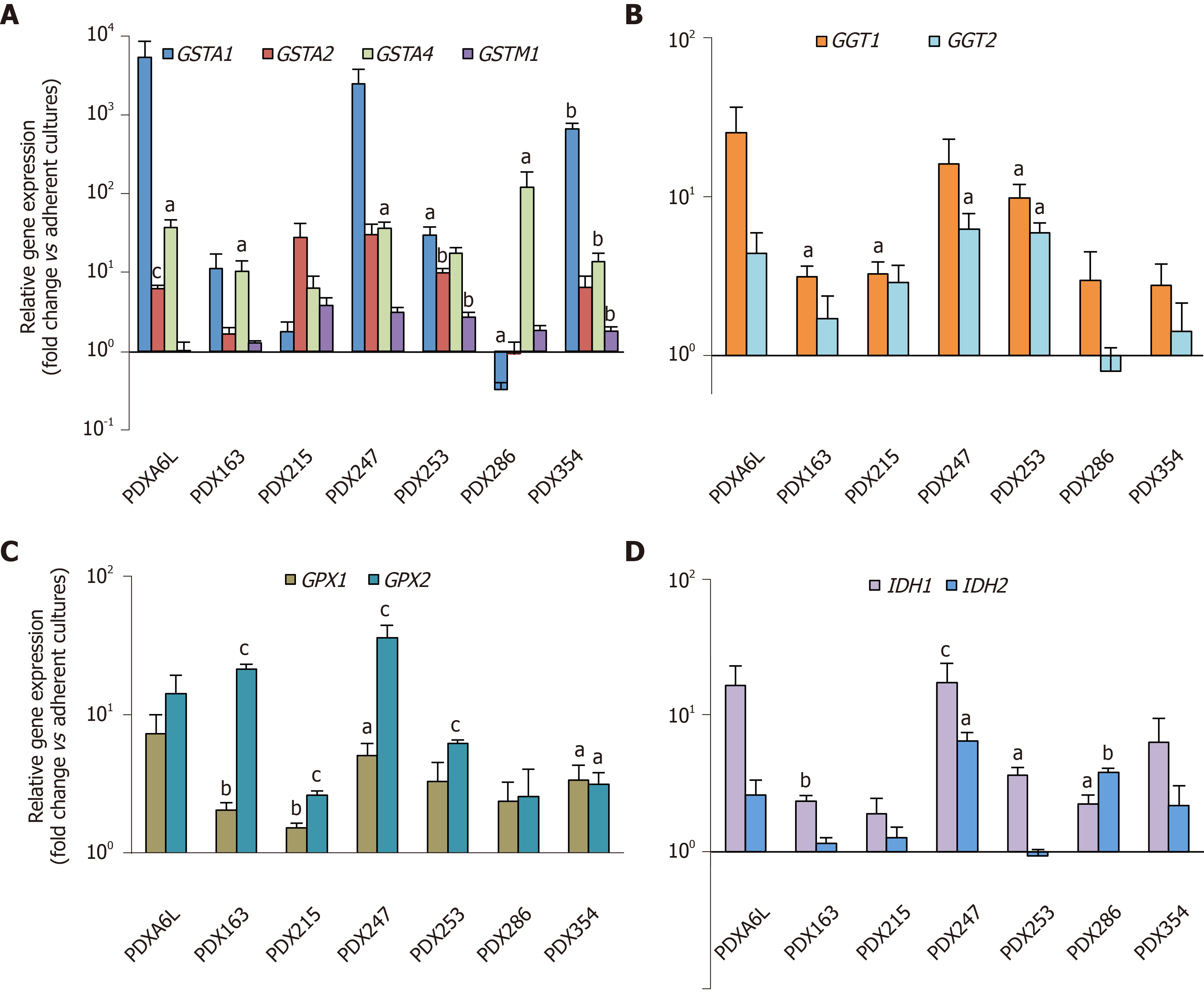

Next, we aimed to further validate the above RNAseq results. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of 2-4 genes from each subgroup by real-time PCR. We included two additional PDX models [one PDAC (PDX163) and one pancreatic tumor of hepatobiliary origin (PDX247)] resulting in a total of seven PDX models for this validation. As shown in Figure 2, we detected enhanced expression of glutathione metabolism genes in CSC-enriching conditions for all seven PDX models, ranging between 2.5 to 600-fold.

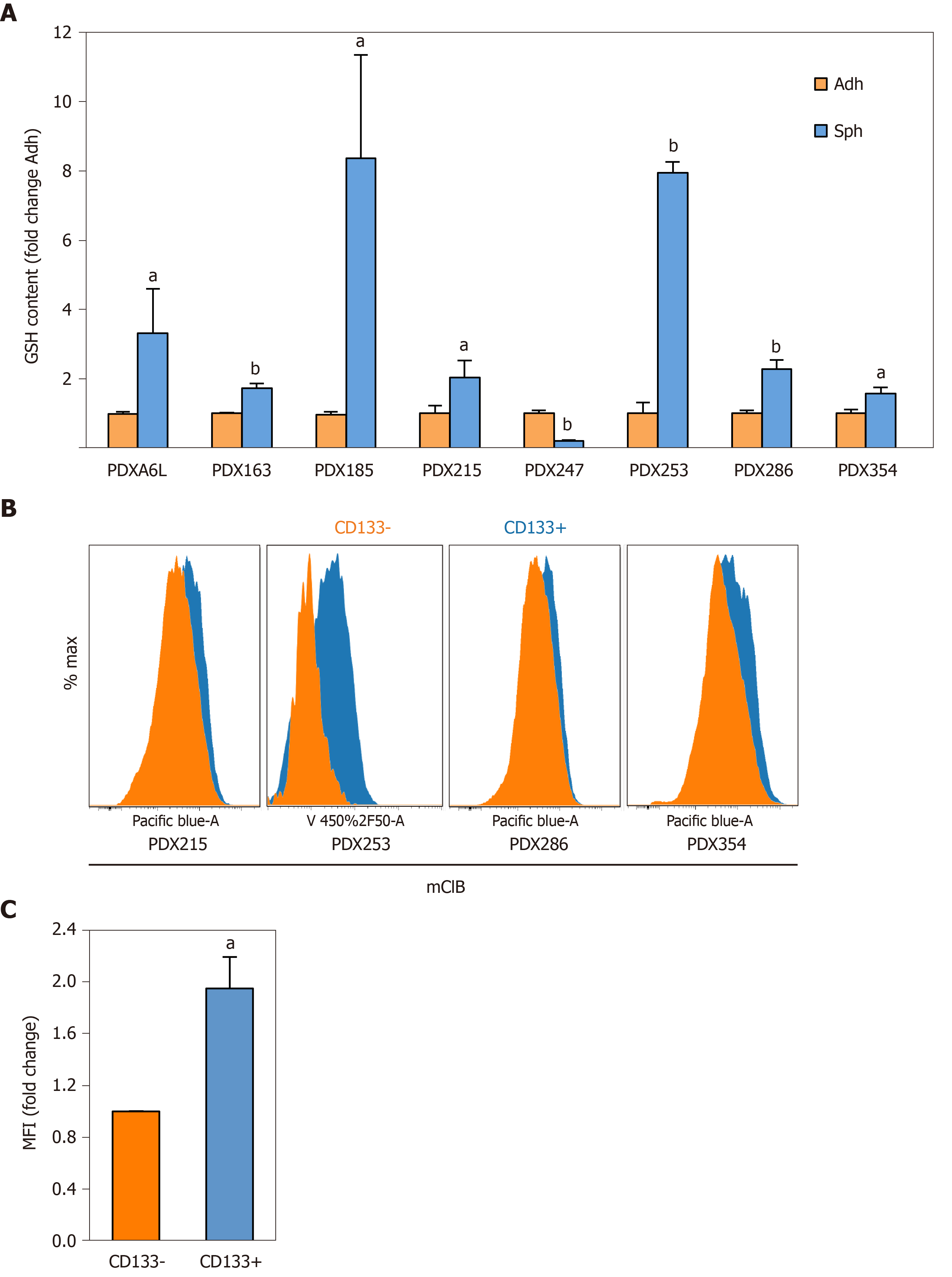

For further functional validation, we used the thiol-sensitive probe monochlorobimane to assess the content of intracellular glutathione content in its reduced form (GSH). First, we measured the GSH content in primary cells cultured in adherent or sphere conditions using the same panel of seven PDX models. Interestingly, except for PDX247 (of hepatobiliary origin) GSH content was 2 to 8 times higher in CSC-enriching conditions (Figure 3A; P values < 0.05-0.01), reinforcing the results obtained by gene expression analysis. Next, we validated the increased GSH levels observed by analyzing CD133– and CD133+ subpopulations by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 3B and 3C, CD133+ CSCs accumulated more intracellular GSH (1.94-fold, P = 0.04). In summary, our results indicate that expression of glutathione metabolism genes and GSH content are upregulated in CSC-enriched conditions.

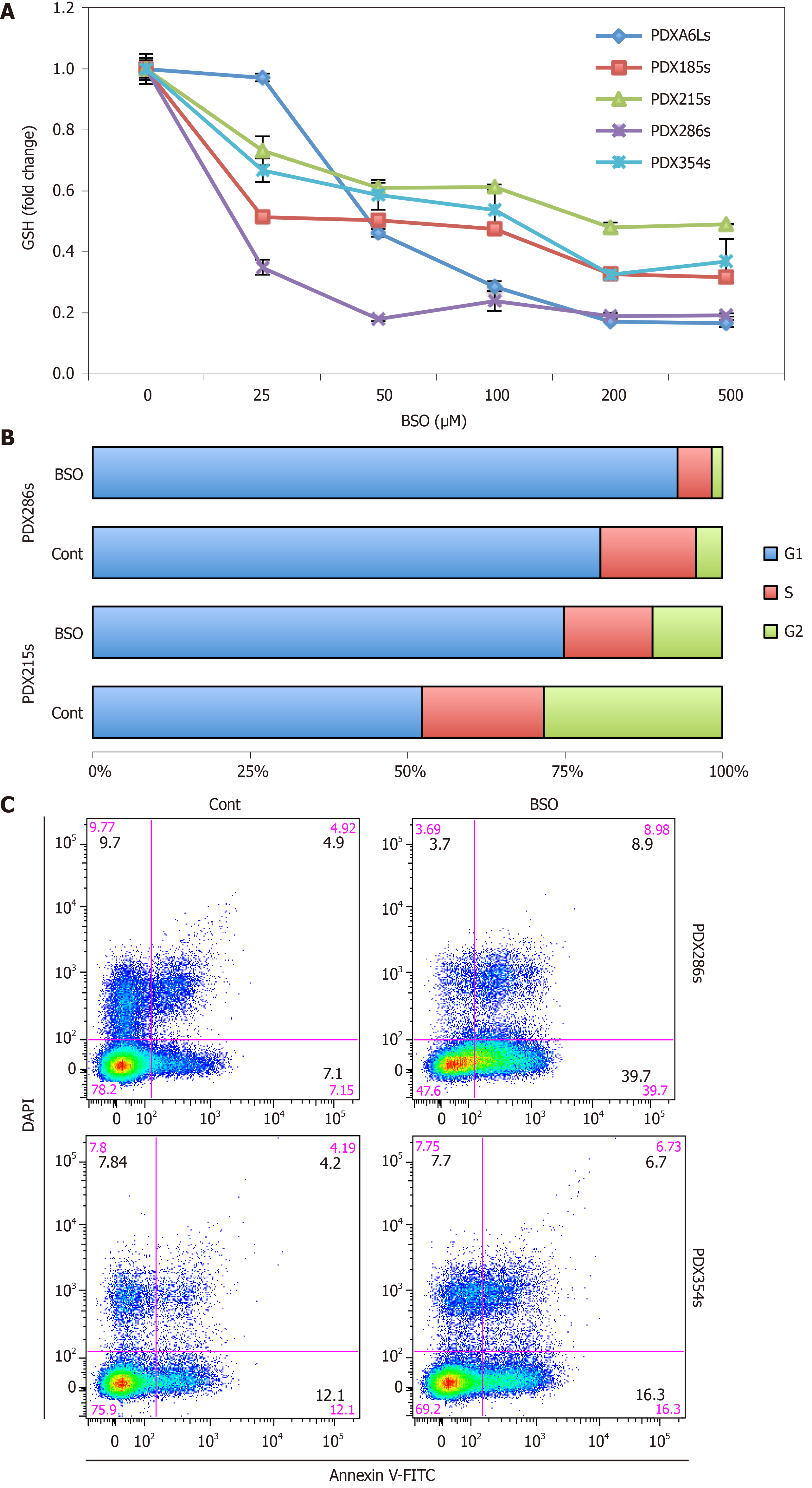

In order to evaluate the significance of the increased GSH content for CSCs, we performed a series of GSH depletion assays using two distinct pharmacological approaches. We first tested the inhibitor of GSH synthesis BSO, which irreversibly blocks the enzyme gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS). Incubation of CSC-enriched spheres with increasing doses of BSO for 48 h resulted in a dose-dependent decline in GSH content, and with doses > 50 µmol/L depleted the GSH content below 50% (Figure 4A; P values ranging between 0.0023 and 0.00032). Treatment of CSC-enriched spheres with BSO at 100 µmol/L for 48 h resulted in the accumulation of cells in G1 phase, indicative of cell cycle arrest (Figure 4B). In addition, we observed an increase in the percentage of cells in both early and late apoptosis after BSO treatment, suggesting that full GSH content is necessary for proliferation and survival of CSCs (Figure 4C).

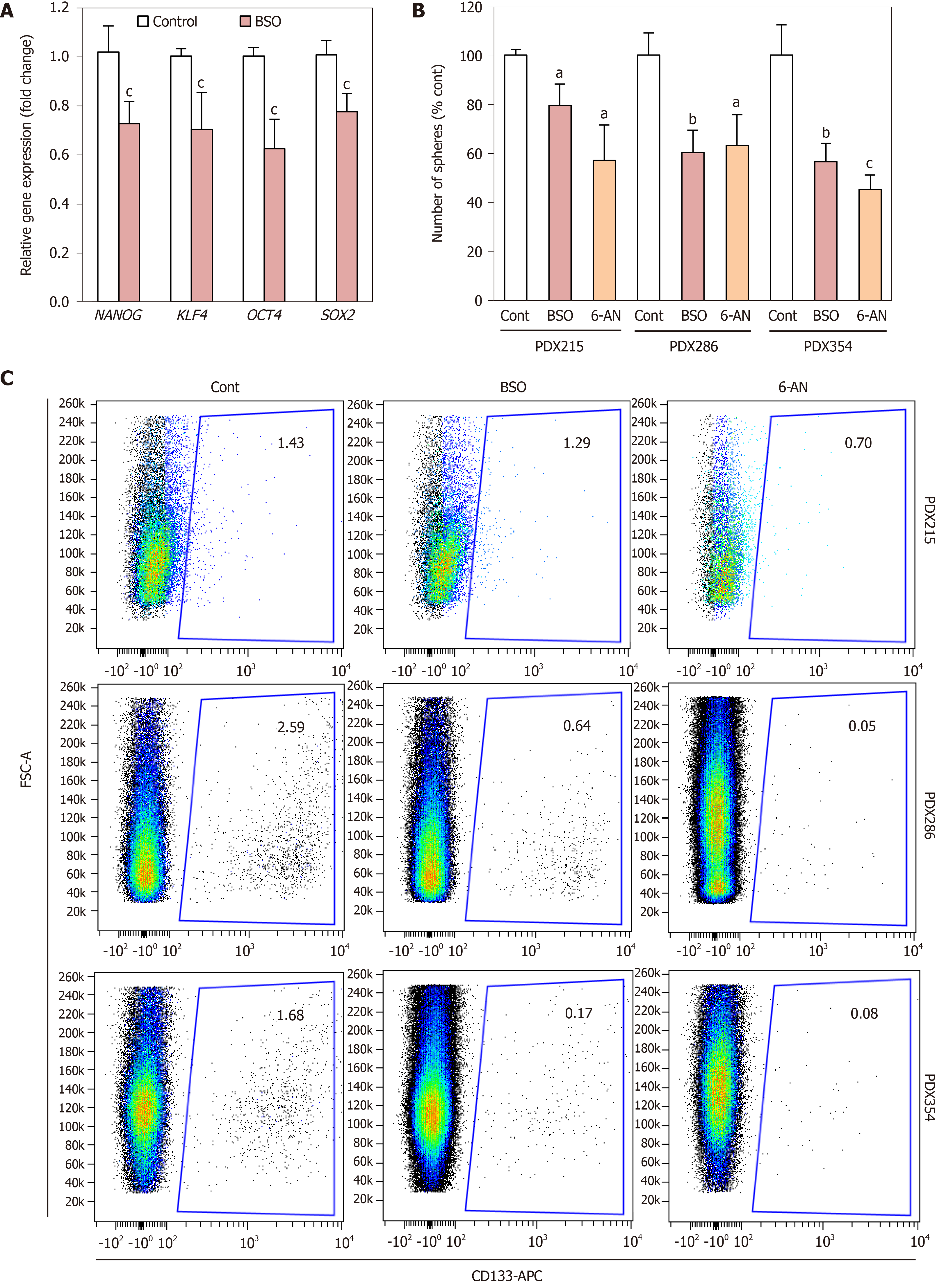

Considering these results, we next focused on alternative features directly linked to CSCs. First, BSO treatment decreased the expression of the aforementioned stemness signature defined by NANOG, KLF4, SOX2 and OCT4 (Figure 5A). Next, we measured the effect of BSO on CSC self-renewal. Since we had observed an up-regulation of genes involved in GSH recycling (Table 2), we also tested the GSH recycling inhibitor 6-aminonicotinamide (6-AN), which blocks the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway that is necessary for reduction of oxidized GSSG into GSH. Incubation with either BSO or 6-AN consistently reduced the number of spheres formed by day 7, indicative of diminished self-renewal capacity (Figure 5B). Consistently, the percentage of CD133+ cells assessed by flow cytometry was also reduced following treatment with either inhibitor (Figure 5C). Together these results indicate that depletion of GSH content directly impacts CSC viability and self-renewal.

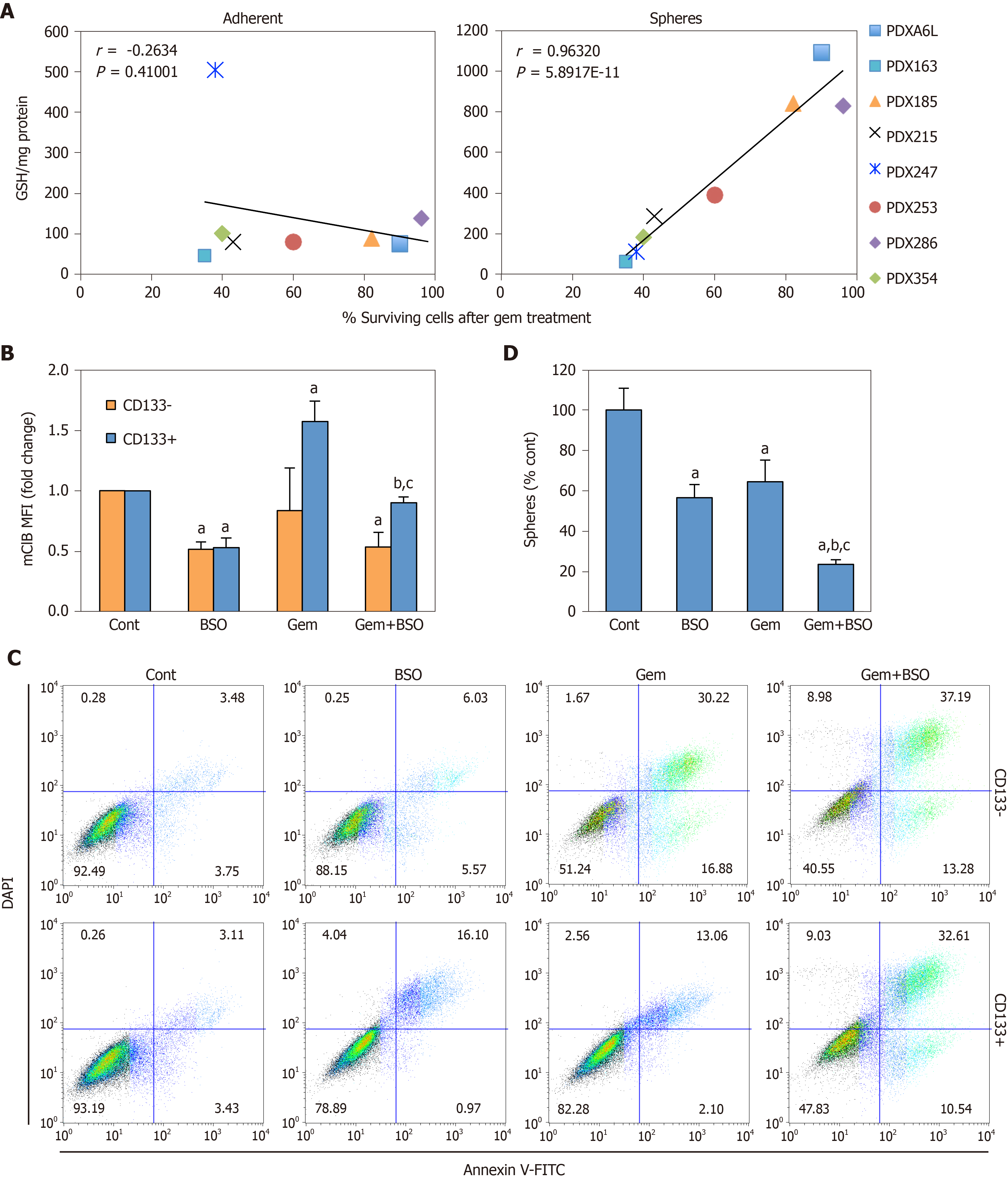

Apart from the ability to self-renew, another key feature of CSCs is chemoresistance. Notably, several glutathione-related enzymes such as GSTs are directly implicated in detoxification of xenobiotics, suggesting another potential link between glutathione metabolism and CSC features[28]. Indeed, we found that the absolute GSH concentration in spheres, but not adherent cultures, positively correlated with the percentage of surviving cells after gemcitabine treatment (Figure 6A; Pearson’s r = 0.96, P = 5.89 × 10-11). Gemcitabine treatment induced GSH accumulation exclusively in CD133+ cells (Figure 6B), which was abrogated by co-treatment with BSO. This translated in sensitization of CD133+ cells to treatment with gemcitabine, approximating levels of apoptosis observed in differentiated CD133– cells (Figure 6C), and diminished sphere formation as compared to single treatments (Figure 6D; P < 0.05). These results demonstrate that chemoresistance in CSCs is, at least in part, dependent on GSH synthesis.

In summary, our results suggest that glutathione metabolism plays an essential role in PDAC aggressiveness, supporting CSC survival, self-renewal and chemoresistance.

Any living cell produces ROS, either as a by-product of mitochondrial respiration or in a controlled manner by different oxidases to modulate cell signaling. Specifically, intracellular ROS levels regulate the complex balance between symmetric and asymmetric division in stem cells, thus controlling differentiation and self-renewal[29]. In these cells, avoiding ROS accumulation is particularly important, since it prevents the accumulation of hereditary mutations and premature senescence[30]. For these reasons, quiescent stem cells reside in a low oxygen niche favoring glycolysis over mitochondrial respiration and express high levels of antioxidant systems[18,31].

Similar to normal stem cells, publications on different cancer types indicate that CSCs have lower ROS levels than their differentiated counterparts to support self-renewal and tumorigenicity[13,14,19]. However, the mechanisms by which they keep a reduced redox state may differ, since many CSCs depend on mitochondrial oxidative metabolism[12,16]. In fact, while glycolysis maintains reduced ROS levels in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic PaTU8988 cells[32], primary human pancreatic CD133+ CSCs have low mitochondrial ROS concomitant with full oxidative metabolic (OXPHOS) activity[7]. These findings suggest that, rather than controlling ROS release from the primary production site, CSCs favor ROS detoxification as a common feature. Indeed, CD44+CD24+ Panc-1 cells survive radiation by blocking ROS accumulation, which also points to increased ROS scavenging in CSCs[33].

GSH is a key antioxidant defense in mammalian cells, maintaining intracellular redox homeostasis. Coupled to different enzymes such as GPXs or GSTs, GSH not only reacts with ROS and electrophiles, but also prevents oxidation of thiol groups in proteins, acts as a cysteine reserve pool, and detoxifies xenobiotics[28]. Interestingly, most of the representative works describing low ROS content in CSCs also reported high levels of GSH and/or GSH-related enzymes. For example, GCLM and GSS were upregulated in liver CD13+N-cadherin- CSCs[19], and GSH content and GPXs expression were increased in gastric CD44+ cells[14]. In addition, breast CSCs defined either as CD24–/Low CD44+Lin– or ALDH+ showed elevated GSH concentration and glutathione synthesis enzymes[13,34], which, in the case of ALDH+ cells, was further enhanced with upregulation of GPXs and GSTs[34,35].

To date, the few published reports connecting glutathione metabolism and stemness-related features in pancreatic cancer have focused on GPXs, with different isoforms playing contradictory roles. On the one hand, GPX1 was described to play a tumor suppressor role counteracting features attributed to CSCs in MiaPaca-2 cells. GPX1 overexpression inhibited clonogenicity and tumor growth in vivo[36], while GPX-1 silencing induced EMT (epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition) and chemoresistance[37]. On the other hand, Panc-1 spheroids up-regulate GPX1 and GPX4 in hypoxic conditions, but only GPX4 seems to be important for self-renewal and invasion under both normoxia and hypoxia[38].

Here, we show that CSC-enriched cultures established from 7 human PDX models not only up-regulate several GPX genes, but also numerous genes related to GSH synthesis and recycling, as well as GSTs (Table 2 and Figure 2). However, although there is a global upregulation of the pathway, our results suggest that expression patterns of the specific isoform(s) of GPXs and GSTs expressed vary considerably across patients (Table 2). This apparent heterogeneity argues against the universality of the previously mentioned studies on GPX isoforms, which were based on just one or two established cell lines[36-38]. Interestingly, our analysis of human normal or PDAC samples indicate a strong correlation of GSH-related genes with stemness and poor outcome (Figure 1). In addition, and in line with the gene expression data, intracellular GSH levels were also increased in spheres and CD133+ cells, respectively, as compared to differentiated cells (Figure 2). Together, these results support the notion that pancreatic CSCs resemble CSCs from other cancer types in terms of glutathione metabolism, and corroborate the evidence for the crucial role of this pathway in cancer stemness.

Oxidative CSCs need to counteract ROS produced in cellular respiration. Notably, enhanced GSH metabolism is often linked to increased mitochondrial function, conferring protection from ROS produced during respiration and by detoxifying lipid hydroperoxides and electrophiles[28]. In fact, glutathione peroxidases such as GPX4 or transferases such as GSTP have been shown to maintain OXPHOS activity and preserve mitochondrial function[39,40]. Importantly, OXPHOS metabolism is linked to glutathione metabolism and antioxidative defense via a process controlled by NRF2, thereby promoting breast CSCs maintenance and self-renewal[34]. In this context, we have previously shown that PGC-1α promotes mitochondrial respiration and is required for full stemness, connecting both processes in pancreatic CSCs[7]. Interestingly, one of the main physiological functions of PGC-1α is to balance mitochondrial ROS production and scavenging by coordinating mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidative response. Indeed, PGC-1α has been shown to control the expression of several antioxidants and glutathione-related enzymes such as GPXs and GSTs, likely via NRF2 activation[41,42]. Moreover, it modulates GSH levels by regulating its synthesis through direct gamma-glutamylcysteine ligase and glutathione synthase transcriptional control[41,43]. Therefore, glutathione metabolism could support stemness downstream of PGC-1α in pancreatic CSCs by detoxifying mitochondrial ROS.

Our results suggest that pancreatic CSCs are particularly sensitive to glutathione depletion. We have shown that inhibition of GSH synthesis induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of pancreatic CSCs (Figure 4), resulting in reduced expression of stemness genes, self-renewal capacity and, consequently, CD133+ content (Figure 5). In contrast, breast and colorectal CSCs seem to be resistant to BSO as a single treatment, and they up-regulate thioredoxins as a compensatory mechanism to counteract ROS and maintain self-renewal under BSO treatment[34,44]. Interestingly, inhibition of self-renewal was achieved not only with the glutathione synthesis inhibitor BSO, but also by pharmacological inhibition of GSH recycling using 6-AN. These results functionally validate our RNAseq data, in which we observed that pancreatic CSCs upregulated genes related to both synthesis (GCLC) and recycling processes (GSR, PGD), and suggest that GSH metabolism is highly dynamic in pancreatic CSCs. Of note, the specific balance of synthesis vs recycling processes determining the actual GSH content may vary between patients. For example, PDX215 cells were partially resistant to BSO, while they responded to 6AN similarly to the other PDXs tested (Figure 5).

Depletion of intracellular GSH with BSO has been shown to sensitize breast CSCs to radiotherapy, inducing oxidative DNA damage that leads to apoptosis[13,45]. However, glutathione synthesis inhibition has been mainly tested in combination with conventional chemotherapy: Treatment with BSO enhanced toxicity of melphalan[46], paclitaxel[47], cisplatin and gemcitabine[48] in different in vitro models, but showed no effect for 5-fluorouracil[46]. Our results further underscore the role of glutathione in chemoresistance, by regulating CSCs survival and functionality. First, we show that GSH content in CSC-enriched cultures, but not in adherent cultures, positively correlates with global survival under gemcitabine treatment (Figure 6A). Moreover, we found that CD133+ cells, but not CD133–, accumulate more intracellular GSH in response to gemcitabine (Figure 6B). Counteracting this defense response by BSO treatment induced apoptosis in both subpopulations to a similar degree (Figure 6C).

Other combination therapies involving glutathione synthesis inhibition have been tested in pancreatic cancer with reasonable success. For instance, inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway in combination with BSO blocked mRNA translation and impaired tumor growth in vivo, mimicking NRF2 loss in pancreatic cancer[49]. Although BSO is the most utilized treatment to achieve GSH depletion, other strategies such as inhibition of cysteine/glutamate transport showed a synergistic effect in combination with gemcitabine for inhibiting proliferation of pancreatic cancer cell lines[50].

In summary, we find that glutathione metabolism plays an essential role in pancreatic cancer aggressiveness, supporting CSC survival, self-renewal and chemoresistance. Our results point to a novel metabolic vulnerability of pancreatic CSCs that should be exploited for the design of new therapeutic strategies aimed at the elimination of this highly aggressive subpopulation of cancer cells.

Redox metabolism modulates stem cell and cancer stem cell (CSC) functionality in different model systems, regardless of their dominant metabolic phenotype. In fact, CSCs from several cancer types show increased glutathione content and associated enzymes.

Identification of metabolic vulnerabilities of highly aggressive CSCs can lead to the development of more effective treatment strategies for pancreatic cancer.

The present study aimed to determine the importance of glutathione metabolism for pancreatic CSCs as compared to their differentiated counterparts.

Comparisons between CSCs and non-CSCs in primary pancreatic cancer cells of patient-derived xenografts were carried out by culturing in adherent or CSC-enriching sphere conditions and confirmed by CD133 staining by flow cytometry. Gene expression analyses were performed by RNAseq or real-time PCR. Public TCGA and GTEx RNAseq data from pancreatic cancer vs normal tissue samples were analyzed using the webserver GEPIA2. Staining for measurement of glutathione (monochlorobimane), cell cycle (propidium iodide) or apoptosis (Annexin-V) were determined by fluorimetry or flow cytometry. Pharmacological glutathione depletion was achieved with inhibitors of glutathione synthesis (buthionine-sulfoximine) and recycling (6-Aminonicotinamide). Self-renewal was assessed by sphere formation assay and response to gemcitabine treatment was used as a readout for chemoresistance.

Several glutathione metabolism genes were upregulated in pancreatic CSCs, and their expression correlates with a stemness signature and predicts survival in clinical samples. Increased glutathione concentration in CSCs promotes viability, cell cycle progression and pluripotency gene expression. Inhibition of glutathione synthesis or recycling impairs CSC functionalities such as self-renewal and chemoresistance.

Our data suggest that pancreatic CSCs depend on glutathione metabolism. Pharmacological targeting of this pathway showed that high GSH (glutathione in its reduced form) content is essential to maintain CSC functionality in terms of self-renewal and chemoresistance.

Our data demonstrate a targetable metabolic vulnerability of this aggressive subpopulation of cancer cells, which could be exploited for therapeutic purposes.

We thank Courtois S, Espiau P and Parejo B for critical reading of the manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge the use of the Cytometry Units from CNIO and IACS-Universidad de Zaragoza.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen Q S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1923-1994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3399] [Cited by in RCA: 3033] [Article Influence: 433.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11065] [Cited by in RCA: 12187] [Article Influence: 1523.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913-2921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5379] [Cited by in RCA: 5140] [Article Influence: 467.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, Aicher A, Ellwart JW, Guba M, Bruns CJ, Heeschen C. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:313-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1987] [Cited by in RCA: 2140] [Article Influence: 118.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lonardo E, Hermann PC, Mueller MT, Huber S, Balic A, Miranda-Lorenzo I, Zagorac S, Alcala S, Rodriguez-Arabaolaza I, Ramirez JC, Torres-Ruíz R, Garcia E, Hidalgo M, Cebrián DÁ, Heuchel R, Löhr M, Berger F, Bartenstein P, Aicher A, Heeschen C. Nodal/Activin signaling drives self-renewal and tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer stem cells and provides a target for combined drug therapy. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:433-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Miranda-Lorenzo I, Dorado J, Lonardo E, Alcala S, Serrano AG, Clausell-Tormos J, Cioffi M, Megias D, Zagorac S, Balic A, Hidalgo M, Erkan M, Kleeff J, Scarpa A, Sainz B Jr, Heeschen C. Intracellular autofluorescence: a biomarker for epithelial cancer stem cells. Nat Methods. 2014;11:1161-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sancho P, Burgos-Ramos E, Tavera A, Bou Kheir T, Jagust P, Schoenhals M, Barneda D, Sellers K, Campos-Olivas R, Graña O, Viera CR, Yuneva M, Sainz B Jr, Heeschen C. MYC/PGC-1α Balance Determines the Metabolic Phenotype and Plasticity of Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells. Cell Metab. 2015;22:590-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 56.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sancho P, Alcala S, Usachov V, Hermann PC, Sainz B Jr. The ever-changing landscape of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Pancreatology. 2016;16:489-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lonardo E, Hermann PC, Heeschen C. Pancreatic cancer stem cells - update and future perspectives. Mol Oncol. 2010;4:431-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cioffi M, Trabulo SM, Sanchez-Ripoll Y, Miranda-Lorenzo I, Lonardo E, Dorado J, Reis Vieira C, Ramirez JC, Hidalgo M, Aicher A, Hahn S, Sainz B Jr, Heeschen C. The miR-17-92 cluster counteracts quiescence and chemoresistance in a distinct subpopulation of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Gut. 2015;64:1936-1948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhou D, Shao L, Spitz DR. Reactive oxygen species in normal and tumor stem cells. Adv Cancer Res. 2014;122:1-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sancho P, Barneda D, Heeschen C. Hallmarks of cancer stem cell metabolism. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:1305-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 46.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, Kalisky T, Dorie MJ, Kulp AN, Qian D, Lam JS, Ailles LE, Wong M, Joshua B, Kaplan MJ, Wapnir I, Dirbas FM, Somlo G, Garberoglio C, Paz B, Shen J, Lau SK, Quake SR, Brown JM, Weissman IL, Clarke MF. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:780-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2102] [Cited by in RCA: 1935] [Article Influence: 120.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ishimoto T, Nagano O, Yae T, Tamada M, Motohara T, Oshima H, Oshima M, Ikeda T, Asaba R, Yagi H, Masuko T, Shimizu T, Ishikawa T, Kai K, Takahashi E, Imamura Y, Baba Y, Ohmura M, Suematsu M, Baba H, Saya H. CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(-) and thereby promotes tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:387-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 837] [Cited by in RCA: 938] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chang CW, Chen YS, Chou SH, Han CL, Chen YJ, Yang CC, Huang CY, Lo JF. Distinct subpopulations of head and neck cancer cells with different levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species exhibit diverse stemness, proliferation, and chemosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6291-6305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jagust P, de Luxán-Delgado B, Parejo-Alonso B, Sancho P. Metabolism-Based Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Cancer Stem Cells. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Calabrese G, Morgan B, Riemer J. Mitochondrial Glutathione: Regulation and Functions. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;27:1162-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jeong EM, Yoon JH, Lim J, Shin JW, Cho AY, Heo J, Lee KB, Lee JH, Lee WJ, Kim HJ, Son YH, Lee SJ, Cho SY, Shin DM, Choi K, Kim IG. Real-Time Monitoring of Glutathione in Living Cells Reveals that High Glutathione Levels Are Required to Maintain Stem Cell Function. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;10:600-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim HM, Haraguchi N, Ishii H, Ohkuma M, Okano M, Mimori K, Eguchi H, Yamamoto H, Nagano H, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M. Increased CD13 expression reduces reactive oxygen species, promoting survival of liver cancer stem cells via an epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like phenomenon. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19 Suppl 3:S539-S548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Harris IS, Treloar AE, Inoue S, Sasaki M, Gorrini C, Lee KC, Yung KY, Brenner D, Knobbe-Thomsen CB, Cox MA, Elia A, Berger T, Cescon DW, Adeoye A, Brüstle A, Molyneux SD, Mason JM, Li WY, Yamamoto K, Wakeham A, Berman HK, Khokha R, Done SJ, Kavanagh TJ, Lam CW, Mak TW. Glutathione and thioredoxin antioxidant pathways synergize to drive cancer initiation and progression. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:211-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in RCA: 699] [Article Influence: 69.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Obrador E, Carretero J, Ortega A, Medina I, Rodilla V, Pellicer JA, Estrela JM. gamma-Glutamyl transpeptidase overexpression increases metastatic growth of B16 melanoma cells in the mouse liver. Hepatology. 2002;35:74-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Obrador E, Benlloch M, Pellicer JA, Asensi M, Estrela JM. Intertissue flow of glutathione (GSH) as a tumor growth-promoting mechanism: interleukin 6 induces GSH release from hepatocytes in metastatic B16 melanoma-bearing mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15716-15727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rocha CR, Kajitani GS, Quinet A, Fortunato RS, Menck CF. NRF2 and glutathione are key resistance mediators to temozolomide in glioma and melanoma cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:48081-48092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mueller MT, Hermann PC, Witthauer J, Rubio-Viqueira B, Leicht SF, Huber S, Ellwart JW, Mustafa M, Bartenstein P, D'Haese JG, Schoenberg MH, Berger F, Jauch KW, Hidalgo M, Heeschen C. Combined targeted treatment to eliminate tumorigenic cancer stem cells in human pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1102-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gallmeier E, Hermann PC, Mueller MT, Machado JG, Ziesch A, De Toni EN, Palagyi A, Eisen C, Ellwart JW, Rivera J, Rubio-Viqueira B, Hidalgo M, Bunz F, Göke B, Heeschen C. Inhibition of ataxia telangiectasia- and Rad3-related function abrogates the in vitro and in vivo tumorigenicity of human colon cancer cells through depletion of the CD133(+) tumor-initiating cell fraction. Stem Cells. 2011;29:418-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8810] [Cited by in RCA: 9319] [Article Influence: 716.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W556-W560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1991] [Cited by in RCA: 3078] [Article Influence: 513.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ribas V, García-Ruiz C, Fernández-Checa JC. Glutathione and mitochondria. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, Matsuoka S, Takubo K, Hamaguchi I, Nomiyama K, Hosokawa K, Sakurada K, Nakagata N, Ikeda Y, Mak TW, Suda T. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431:997-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 901] [Cited by in RCA: 920] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yahata T, Takanashi T, Muguruma Y, Ibrahim AA, Matsuzawa H, Uno T, Sheng Y, Onizuka M, Ito M, Kato S, Ando K. Accumulation of oxidative DNA damage restricts the self-renewal capacity of human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2011;118:2941-2950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Oburoglu L, Tardito S, Fritz V, de Barros SC, Merida P, Craveiro M, Mamede J, Cretenet G, Mongellaz C, An X, Klysz D, Touhami J, Boyer-Clavel M, Battini JL, Dardalhon V, Zimmermann VS, Mohandas N, Gottlieb E, Sitbon M, Kinet S, Taylor N. Glucose and glutamine metabolism regulate human hematopoietic stem cell lineage specification. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:169-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhao H, Duan Q, Zhang Z, Li H, Wu H, Shen Q, Wang C, Yin T. Up-regulation of glycolysis promotes the stemness and EMT phenotypes in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:2055-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wang L, Li P, Hu W, Xia Y, Hu C, Liu L, Jiang X. CD44+CD24+ subset of PANC-1 cells exhibits radiation resistance via decreased levels of reactive oxygen species. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:1341-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Luo M, Shang L, Brooks MD, Jiagge E, Zhu Y, Buschhaus JM, Conley S, Fath MA, Davis A, Gheordunescu E, Wang Y, Harouaka R, Lozier A, Triner D, McDermott S, Merajver SD, Luker GD, Spitz DR, Wicha MS. Targeting Breast Cancer Stem Cell State Equilibrium through Modulation of Redox Signaling. Cell Metab 2018; 28: 69-86. e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lu H, Chen I, Shimoda LA, Park Y, Zhang C, Tran L, Zhang H, Semenza GL. Chemotherapy-Induced Ca2+ Release Stimulates Breast Cancer Stem Cell Enrichment. Cell Rep. 2017;18:1946-1957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu J, Hinkhouse MM, Sun W, Weydert CJ, Ritchie JM, Oberley LW, Cullen JJ. Redox regulation of pancreatic cancer cell growth: role of glutathione peroxidase in the suppression of the malignant phenotype. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:239-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Meng Q, Shi S, Liang C, Liang D, Hua J, Zhang B, Xu J, Yu X. Abrogation of glutathione peroxidase-1 drives EMT and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer by activating ROS-mediated Akt/GSK3β/Snail signaling. Oncogene. 2018;37:5843-5857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Peng G, Tang Z, Xiang Y, Chen W. Glutathione peroxidase 4 maintains a stemness phenotype, oxidative homeostasis and regulates biological processes in Panc-1 cancer stem-like cells. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:1264-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Cole-Ezea P, Swan D, Shanley D, Hesketh J. Glutathione peroxidase 4 has a major role in protecting mitochondria from oxidative damage and maintaining oxidative phosphorylation complexes in gut epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:488-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fujitani N, Yoneda A, Takahashi M, Takasawa A, Aoyama T, Miyazaki T. Silencing of Glutathione S-Transferase Pi Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth via Oxidative Stress Induced by Mitochondria Dysfunction. Sci Rep. 2019;9:14764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Aquilano K, Baldelli S, Pagliei B, Cannata SM, Rotilio G, Ciriolo MR. p53 orchestrates the PGC-1α-mediated antioxidant response upon mild redox and metabolic imbalance. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:386-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Marmolino D, Manto M, Acquaviva F, Vergara P, Ravella A, Monticelli A, Pandolfo M. PGC-1alpha down-regulation affects the antioxidant response in Friedreich's ataxia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Vazquez F, Lim JH, Chim H, Bhalla K, Girnun G, Pierce K, Clish CB, Granter SR, Widlund HR, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. PGC1α expression defines a subset of human melanoma tumors with increased mitochondrial capacity and resistance to oxidative stress. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:287-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Tanaka G, Inoue K, Shimizu T, Akimoto K, Kubota K. Dual pharmacological inhibition of glutathione and thioredoxin systems synergizes to kill colorectal carcinoma stem cells. Cancer Med. 2016;5:2544-2557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Miran T, Vogg ATJ, Drude N, Mottaghy FM, Morgenroth A. Modulation of glutathione promotes apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 2018;32:2803-2813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Schnelldorfer T, Gansauge S, Gansauge F, Schlosser S, Beger HG, Nussler AK. Glutathione depletion causes cell growth inhibition and enhanced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer. 2000;89:1440-1447. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Ramanathan B, Jan KY, Chen CH, Hour TC, Yu HJ, Pu YS. Resistance to paclitaxel is proportional to cellular total antioxidant capacity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8455-8460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Li Q, Yin X, Wang W, Zhan M, Zhao B, Hou Z, Wang J. The effects of buthionine sulfoximine on the proliferation and apoptosis of biliary tract cancer cells induced by cisplatin and gemcitabine. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:474-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Chio IIC, Jafarnejad SM, Ponz-Sarvise M, Park Y, Rivera K, Palm W, Wilson J, Sangar V, Hao Y, Öhlund D, Wright K, Filippini D, Lee EJ, Da Silva B, Schoepfer C, Wilkinson JE, Buscaglia JM, DeNicola GM, Tiriac H, Hammell M, Crawford HC, Schmidt EE, Thompson CB, Pappin DJ, Sonenberg N, Tuveson DA. NRF2 Promotes Tumor Maintenance by Modulating mRNA Translation in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell. 2016;166:963-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Lo M, Ling V, Wang YZ, Gout PW. The xc- cystine/glutamate antiporter: a mediator of pancreatic cancer growth with a role in drug resistance. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:464-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |