修回日期: 2024-05-01

接受日期: 2024-05-22

在线出版日期: 2024-06-28

结直肠癌(colorectal cancer, CRC)作为第四大致死性癌症. 流行病学调查显示, 遗传和环境风险有助于CRC的发展. 肠道菌群失调在CRC患者中普遍存在. 伴随着组学的不断发展, 在CRC形成过程中, 具核梭杆菌、大肠埃希氏菌、脆弱类杆菌等在促进癌变进程中的机制被逐渐揭晓. "司机-乘客"模型为我们解析了肠道菌群在促进息肉、腺瘤和CRC转变进程中的作用, 致病菌通过占据有利生态位, 与宿主相互作用, 刺激炎症、调控代谢、产生基因毒素、集聚突变等最终创造有利于癌细胞成长的微环境, 诱发癌变. 肠道微生物结合现有的结肠镜筛查和粪便免疫化学试验(fecal immunochemical test, FIT), 可提升CRC检测准确性(area under curve, AUC)高达0.96, 对早期腺瘤的检测准确性高达0.89, 同时具核梭杆菌可以作为预后标记物, 这为CRC的早筛和预后评估提供了现实的可操控性. 同时肠道菌群在CRC的免疫治疗和化疗中发挥重要作用.

核心提要: 遗传、环境和肠道菌群失调与结直肠癌(colorectal cancer, CRC)发生密不可分. 而肠道菌群、结肠镜及粪便免疫化学试验可提升CRC检测准确性, 肠道菌群可作为早筛和预后的标记物, 此外, 肠道菌群在CRC的免疫治疗和化疗中具有重要价值.

引文著录: 杨立顺, 高程, 康建华. 肠道微生物与结直肠癌发生的相关性和其潜在应用研究. 世界华人消化杂志 2024; 32(6): 418-423

Revised: May 1, 2024

Accepted: May 22, 2024

Published online: June 28, 2024

Colorectal cancer (CRC), as the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths, presents a significant public health challenge. Epidemiological studies indicate that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development of CRC. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is commonly observed in CRC patients. With the continuous advancement of omics technologies, the mechanisms by which microorganisms such as Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum), Escherichia coli, and Bacteroides fragilis promote carcinogenesis in CRC have gradually been elucidated. The "driver-passenger" model helps us understand the role of the gut microbiota in promoting the progression from polyps to adenomas and CRC. Pathogenic bacteria create a favorable microenvironment for cancer cell growth by occupying advantageous ecological niches, interacting with the host, stimulating inflammation, regulating metabolism, producing genotoxins, and accumulating mutations. Combining gut microbiota analysis with existing screening methods such as colonoscopy and fecal immunochemical testing significantly enhances the accuracy of CRC detection, with an area under the curve as high as 0.96, and a detection accuracy of 0.89 for early adenomas. Moreover, F. nucleatum can serve as a prognostic biomarker, providing practical manipulability for early screening and prognostic assessment of CRC. Additionally, the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in immunotherapy and chemotherapy of CRC.

- Citation: Yang LS, Gao C, Kang JH. Correlation between intestinal microbiota and occurrence of colorectal cancer: Potential applications. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2024; 32(6): 418-423

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v32/i6/418.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v32.i6.418

结直肠癌(colorectal cancer, CRC)又称大肠癌、大肠直肠癌或肠癌, 为源自直肠或大肠的癌症. CRC作为严重威胁人类健康的癌症之一, 目前全球每年有约185万的新发病例, 约有85万人死于CRC, 全球CRC防治面临着严峻的形势[1]. 中国作为癌症病发大国, 2016年新发CRC约41万例, 死亡约20万例[2], 散发性年轻发病病例逐年增加, CRC的多发性严重影响着人民大众的健康生活.

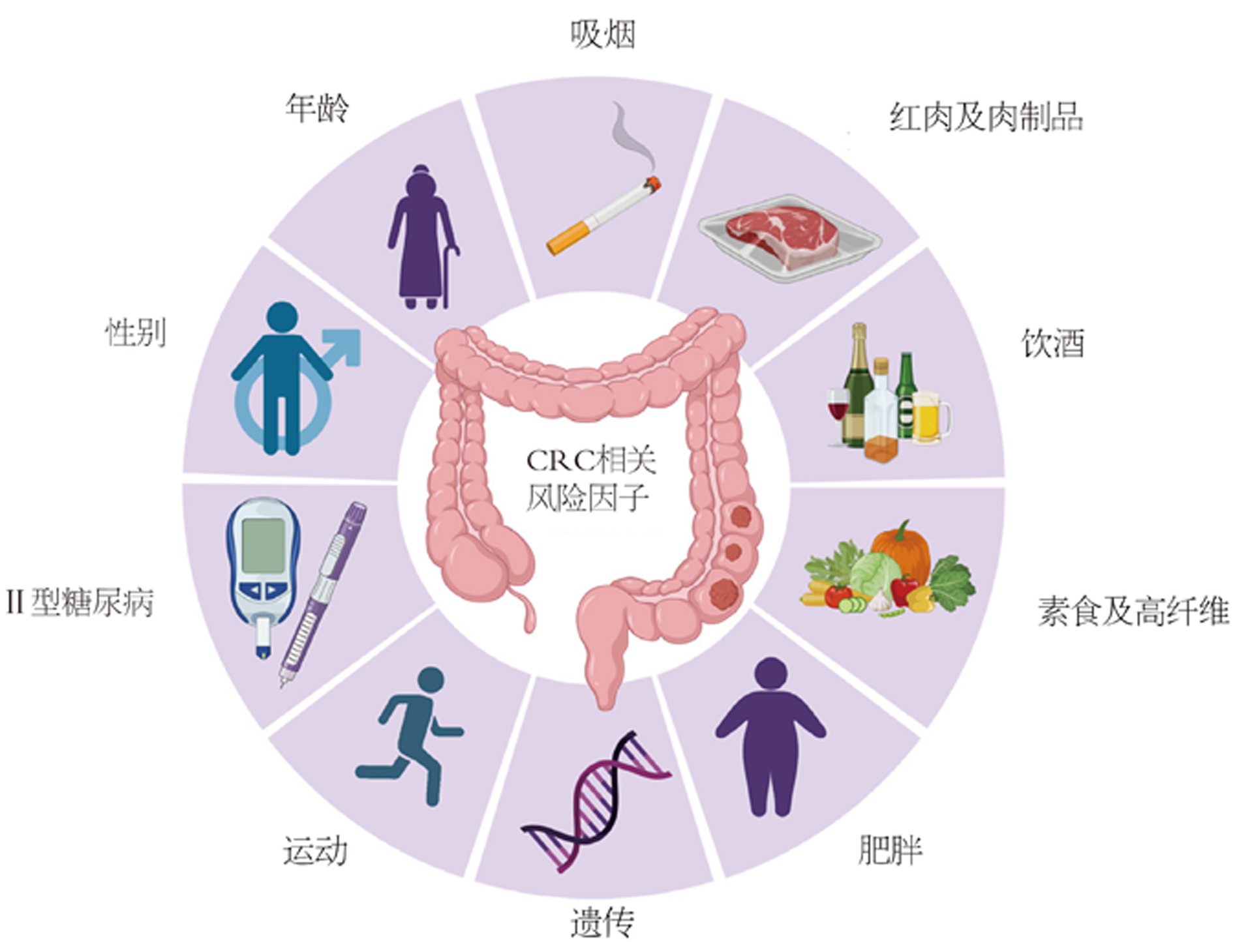

与许多其他肿瘤的发生机制类似, 肠肿瘤的形成是遗传与环境相互作用所引起的[3]. 10%-20%的CRC患者有家族史, 并且罹患病的风险与亲属患病数量、程度和年龄等密切相关[4,5]. 遗传性CRC可以进一步细分为非息肉性(林奇综合征和家族性CRC)和息肉性CRC. 除了年龄因素外, 肥胖, 缺乏体育锻炼, 西式的饮食与膳食纤维的缺乏等均为CRC病发的风险因子, 此外流行病调查发现, 女性CRC发病和致死率大约比男性低约25%[6](图1). 同时, 在54597名非裔美国人的统计调查结果显示, 糖尿病与CRC的发生存在显著相关, 进行有效的糖尿病控制可能降低CRC的发生[7]. 微生态研究表明, 特定微生物的感染, 可能在无形中增加了CRC的风险[8-10]. CRC患者与正常群体相比, 肠道微生物的组成和肠道微生态均有较大差异, 功能学的研究和动物模型也指出, 几种细菌在CRC进展中扮演重要的角色, 例如具核梭杆菌、大肠埃希菌、脆弱类杆菌等[11,12].

通过荟萃分析, 本文将从肠道微生态与CRC的关联性, 肠道微生物用于CRC筛查和预后评估的标记物, 肠道微生态调控和改善用于CRC的预防和治疗可行性方面进行论述, 以期为CRC的防治提供更多的证据.

CRC的发展进程, 从单发性的息肉, 进展到早期腺瘤和晚期腺瘤, 最终进展到癌, 侵入肠粘膜组织, 这个过程包括一系列的遗传突变, 包括腺瘤性息肉病基因的丢失, 鼠类肉瘤病毒癌基因(Kristen rat sarcoma, KRAS)、磷脂酰肌醇-3-激酶催化σ亚基(phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha, PIK3CA)、p53蛋白的激活等[13]. Grivennikov等[14]研究发现, CRC的发生是基因突变和微生物共同作用的结果, 上皮细胞的遗传突变, 会导致连接蛋白的丢失, 从而导致肠粘膜完整性破坏, 这时微生物会由腔管进入到固有层, 细菌产物与toll样受体(toll-like receptors, TLR)结合, 促进白细胞介素(interleukin, IL)-1、IL-6、IL-23的释放, 进而进一步驱动信号转导和激活转录本3的激活, 导致异常的上皮细胞进一步增生、存活, 从而形成信号的级联放大效果, 导致突变的进一步积累, 最终发展为浸润性的癌症.

成人的肠道栖息着大约1000多种微生物物种, 微生物含量高达1014个[15], 小肠管腔中微生物的含量高达108个/毫升, 而大肠中管腔含量高达惊人的1011个/毫升[16], 健康人群中肠道微生物群主要由四个门组成, 其中厚壁菌门、拟杆菌门占据微生物群的90%以上, 同时含有少量的放线菌门、变形菌门以及疣微菌门, 大多数的细菌栖息于胃肠消化道, 厌氧菌主要定植于大肠中[17], 人体内肠道菌群的扰动, 与许多肠道疾病相关, 例如肠易激综合征、炎症性肠病(包括溃疡性肠病和克罗恩病)、CRC[18]. CRC中另一个重要因素是肿瘤的侧边性和微生物的空间分布, 右侧的CRC(包括盲肠、升结肠和肝曲)和左侧(包括脾曲、降结肠、乙状结肠和直肠乙状结肠)在生物学、病理学、流行病学等方面具有差异. 右侧肿瘤呈现粘液和印戒组织学, 微卫星不稳定性高, CpG岛甲基化高, 分化低, 免疫浸润, PIK3CA、KRAS、V-raf鼠肉瘤病毒癌基因同源体B突变率高, 多发于老年和妇女. 总体预后差, 并且表现为抗-表皮生长因子受体和抗-血管内皮生长因子治疗[19]. 微生物常侵入结肠隐窝. 同时, 微生物的多样性和丰度与左侧相比也存在较大差异[11].

随着16S rRNA测序和宏基因组测序技术的不断成熟, 许多细菌的疾病模型被建立, 致病机制正逐渐被揭晓, 具核梭杆菌通过microRNA介导激活Toll受体(TLR2/TLR4)信号从而抑制凋亡[20]; 脆弱类杆菌通过分泌毒素蛋白, 引起肠粘膜免疫反应和结肠上皮细胞的改变从而起到促癌作用[21]; 消化链球菌通过营造酸性的缺氧的肿瘤微环境, 从而促进癌症的发生; 大肠埃希菌通过产生基因毒素介导DNA损伤; 另外一些细菌通过代谢物, 在宿主免疫系统与癌细胞之间建立交互作用, 例如, 微生物代谢产物L-2-羟戊二酸、D-2-羟戊二酸、琥珀酸盐、延胡索酸盐、乳酸盐等在癌细胞的集聚, 而一些代谢产物, 如乳酸可以作为癌细胞生长的营养并且促进癌症进展, 而丁酸盐则可能抑制促炎基因和肿瘤的生长[11].

同时, 我们也不应该忽略真菌在CRC病程中的作用, 通过宏基因组测序184例CRC, 197例腺瘤和204例健康群体表明担子菌门与子囊菌门在CRC患者肠道内存在严重的比例失衡, CRC患者肠道内的某些真菌丰度显著高于健康群体, 如马拉色菌、Moniliophthtora、红酵母、Acremonium、根串珠霉、Pisolithus[22,23].

细菌与真菌的致癌机制目前已在多种癌症发病机制中得到了充分的研究, 包括胃癌、淋巴癌、Merkel细胞癌、宫颈癌和肝癌. 然而, 目前尚不清楚病毒与CRC发生的关系[24,25].

传统的CRC筛查方式包括结肠镜、乙状结肠镜、结肠CT成像技术、FIT、多靶点粪便FIT-DNA[26]. 结肠镜作为检测CRC的金标准, 属于侵入性操作, 肠出血率和穿孔率为万分之22.4和6.4, 并且病患依从性较差, 而结肠CT成像技术虽然可以无创检查CRC, 但在人群筛查中仍有一定的局限性, 需要严格的肠道准备, 专业设备和技术人员, 放射线辐射等, 多靶点的粪便FIT-DNA联合检测(包括FIT与KRAS突变、NDRG4甲基化和BMP3甲基化)相较于常规的FIT具有更高的灵敏度, 但是对早期腺癌的诊断灵敏度只有42.4%. 随着测序技术的不断成熟和肠道微生态研究的不断深入, 体外研究与动物模型的建立, 研究者逐渐将目光转移到菌群失调与CRC发生、发展、转移的关系上. 通过对不同地域的526份样本进行宏基因组测序, 7种与CRC相关的细菌标记物被鉴定(包括脆弱类杆菌、具核梭杆菌、不解糖卟啉单胞菌、微小微单胞菌、中间普雷沃菌、Alistipes finegoldii、Thermanaerovibrio acidaminovorans), 且其与健康群体相比较, 检测准确性为0.8[27], 这表明肠道菌群可作为潜在的诊断标志物. 而FIT结合多种细菌标记进行qPCR, 可以提升检测的准确性0.89-0.96[28-30], 而有报道FIT结合具核梭杆菌也能将检测准确性提升到0.95[31]. 这实现了高效、低成本、实时的检测. Wu等[32]通过对1056例粪便样本分析, 鉴定了26个微生物标记, 利用随机森林法对模型进行优化发现, 利用11个和26个微生物标记进行结直肠早期腺瘤检测的准确性分别为0.80和0.89, 而通过验证数据进行模型确认后, 检测准确性为0.78和0.84, 这远优于多靶点FIT对早期腺瘤的检测.

具核梭杆菌作为肠道内一种特所的菌种, 在多项研究中发现其丰度介于正常人和CRC患者之间[29,33-36], 并且目前也有多项研究报道了其结合多种微生物标记物或者FIT用于腺瘤的诊断[37,38]. 与具核梭杆菌阴性的相比, 低丰度的具核梭杆菌风险比(hazard ratio, HR)是1.25, 而高丰度的HR是1.58[39]. Chen等[40]从高风险II期和III期的CRC病人处获得了91份CRC组织样本, 通过比较分析, 发现瘤体内具核梭杆菌的增加会导致神经浸润, 血管肿瘤血栓和微卫星的突变, 导致预后较差. Lee等[41]研究发现, 右侧结肠丰富的具核梭杆菌与OS无关, 而右侧结肠具核梭杆菌丰度高的病人有更短的一线治疗后无疾病进展期(progression-free survival, PFS)(9.7 mo vs 11.2 mo)和更短的二线治疗后PFS(3.7 mo vs 6.7 mo). 这些发现, 提示我们可以利用肠道菌群, 如具核梭杆菌丰度作为预后标记物, 同时也提醒我们, 可以通过调控具核梭杆菌丰度来改善预后和提高生存率.

预防是一项降低疾病负担的优选措施, 流行病学调查显示超过一半的CRC可以通过生活方式的改变进行预防, 包括饮食、肥胖、体育锻炼和健康规律的生活方式. 一项在非裔美国人和土著非洲人的研究表明[42], 高蛋白、高脂的摄入与低膳食纤维的摄入与CRC的发生息息相关, 非裔美国人肠道菌群中含有更高丰度的拟杆菌. 而通过饮食干预能够重塑肠道菌群, 从而在更深层次影响CRC的发生. 有意思的是, 当我们调整研究中非裔美国人的饮食为高纤维、低脂两周时间后, 能够提升肠道菌群多样性, 并且降低炎症和肿瘤细胞增殖标记[43]. 相反, 转变土著非洲人的饮食到高脂、低纤维则会导致肿瘤风险相关的黏膜标记增加. 纤维主要包括可溶性纤维和不可溶性纤维, 如果聚糖和半乳糖寡糖, 通过改变胃肠道微生物的组成, 增加有益菌双歧杆菌和乳酸杆菌, 并且可增加粪便中的丁酸盐浓度. 而红肉以及肉制品的摄入过量(>140 g/d), 则可能增加CRC风险[44]. 同时, 一项历时长达7年的随访调查也显示, 长期的坚持使用素食也会降低CRC风险[45]. 肥胖是诱发CRC发生的另一重要因子, 当人体身体质量指数>27 kg/m2, 罹患CRC的风险增高[46]. 这些研究提示我们健康科学的饮食管理和日常体育锻炼在预防CRC中的重要潜能.

大量的研究表明益生菌(包括双歧杆菌、乳酸杆菌)通过抑制癌细胞增殖, 诱导凋亡, 调控宿主免疫, 失活致癌毒素和产生抗癌物质, 从而起到抗癌功效. 临床研究也表明, 口服Lactobacillus casei可以降低肿瘤的发生[47], 而合成的益生菌Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG、Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12可以诱导结直肠息肉患者粪便微生物群的改变, 从而降低细胞增殖、改善肠壁功能[48]. 尽管已有许多的实验数据支持益生菌在预防CRC中的功效, 但是, 我们仍然需要更多的试验去验证益生菌在防治CRC中临床作用.

肠道菌群除了在癌变和肿瘤进展发挥重要作用外, 越来越多的证据表明, 肠道菌群在化疗和免疫治疗中发挥重要作用. 在癌症免疫治疗中, 宿主免疫与肠道菌群之间存在复杂的交互反应, 病原菌对肿瘤具有免疫调控作用, 而肿瘤反过来也会影响宿主的肠道微生物组成, 同时某些细菌的代谢产物可能影响免疫过程, 例如厚壁菌门的某些菌株可通过分泌丁酸盐抑制组蛋白去乙酰化, 从而抑制多种致癌信号通路和炎症反应, 从而抑制CRC发展[49]. 此外, 肠道菌群也能够通过微生物移位、免疫调控、代谢、酶促降解和生态多样性的降低, 来影响化疗药物的抗癌效果, 例如具核梭杆菌能够激活细胞自噬从而产生奥利沙铂和5-氟尿嘧啶抗药性[50]. 同时研究也发现肠道菌群能够改善PD-1的抗肿瘤效果, 宏基因组揭示了免疫阻断点与肠道Akkermansia muciniphila的丰度相关, 在进行了粪菌移植(fecal microbiota transplantation, FMT)后, IL-12介导了CCR9+CXCR3+CD4+T淋巴细胞的募集, 从而逆转了PD-1的阻断作用[51]. 晚期CRC患者5年生存率不足10%, CRC患者在接受一段时间化疗后, 出现抗药性, 而抗药的出现与肠道微生物密切相关. 近年来FMT在治疗难治梭菌感染上取得丰硕的成果, 虽然FMT在治疗CRC中的效果还有待检验, 但是现在依然有许多的试验去调查其在免疫治疗和化疗中的作用[25,52].

人类作为一个微生物集合体, 肠道内的菌群处于动态平衡中, 而这种生态平衡一旦被打破, 疾病也就接踵而至, 体内微生态的维持, 是一个长期而持久的过程, 正所谓防病防口, 我们应该将饮食以及生活习惯的改变, 作为预防CRC发生发展的重要举措, 同时在传统诊疗手段的基础上, 应该结合新的前沿研究成果, 应用于CRC诊疗上, 可以将肠道的甚至口腔的某些微生物作为诊断评估CRC的重要生物标记, 同时在治疗CRC时可以辅以肠道微生态菌群的调节或改善, 标本兼治, 同时我们也应该科学, 直观的审视目前的FMT在治疗难治的肠道病原菌感染以及CRC术后恢复治疗的疗效. 总之, 以肠道微生态为突破口, 或许可以让广大的CRC患者受益, 同时也为我们科学的防癌治癌提供新的解决办法.

学科分类: 胃肠病学和肝病学

手稿来源地: 天津市

同行评议报告学术质量分类

A级 (优秀): 0

B级 (非常好): B, B

C级 (良好): 0

D级 (一般): D

E级 (差): 0

科学编辑: 张砚梁 制作编辑:张砚梁

| 1. |

Chhikara BS, Parang K. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: the trends projection analysis.

Chemical Biology Letters. 2023;10:451-451 Available from: |

| 2. | Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, Li L, Wei W, He J. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016. Journal of the National Cancer Center. 2022;2:1-9. [DOI] |

| 3. | Xing C, Du Y, Duan T, Nim K, Chu J, Wang HY, Wang RF. Interaction between microbiota and immunity and its implication in colorectal cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:963819. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Henrikson NB, Webber EM, Goddard KA, Scrol A, Piper M, Williams MS, Zallen DT, Calonge N, Ganiats TG, Janssens AC, Zauber A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Whitlock EP. Family history and the natural history of colorectal cancer: systematic review. Genet Med. 2015;17:702-712. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Schoen RE, Razzak A, Yu KJ, Berndt SI, Firl K, Riley TL, Pinsky PF. Incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1438-1445.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394:1467-1480. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Lawler T, Walts ZL, Steinwandel M, Lipworth L, Murff HJ, Zheng W, Warren Andersen S. Type 2 Diabetes and Colorectal Cancer Risk. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2343333. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Iadsee N, Chuaypen N, Techawiwattanaboon T, Jinato T, Patcharatrakul T, Malakorn S, Petchlorlian A, Praditpornsilpa K, Patarakul K. Identification of a novel gut microbiota signature associated with colorectal cancer in Thai population. Sci Rep. 2023;13:6702. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Pandey H, Tang DWT, Wong SH, Lal D. Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer: Biological Role and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Bai X, Wei H, Liu W, Coker OO, Gou H, Liu C, Zhao L, Li C, Zhou Y, Wang G, Kang W, Ng EK, Yu J. Cigarette smoke promotes colorectal cancer through modulation of gut microbiota and related metabolites. Gut. 2022;71:2439-2450. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Wong SH, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:690-704. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Ternes D, Karta J, Tsenkova M, Wilmes P, Haan S, Letellier E. Microbiome in Colorectal Cancer: How to Get from Meta-omics to Mechanism? Trends Microbiol. 2020;28:401-423. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Gallimore AM, Godkin A. Epithelial barriers, microbiota, and colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:282-284. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Grivennikov SI, Wang K, Mucida D, Stewart CA, Schnabl B, Jauch D, Taniguchi K, Yu GY, Osterreicher CH, Hung KE, Datz C, Feng Y, Fearon ER, Oukka M, Tessarollo L, Coppola V, Yarovinsky F, Cheroutre H, Eckmann L, Trinchieri G, Karin M. Adenoma-linked barrier defects and microbial products drive IL-23/IL-17-mediated tumour growth. Nature. 2012;491:254-258. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Xie Y, Hu F, Xiang D, Lu H, Li W, Zhao A, Huang L, Wang R. The metabolic effect of gut microbiota on drugs. Drug Metab Rev. 2020;52:139-156. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Rivière A, Selak M, Lantin D, Leroy F, De Vuyst L. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:979. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Sasso JM, Ammar RM, Tenchov R, Lemmel S, Kelber O, Grieswelle M, Zhou QA. Gut Microbiome-Brain Alliance: A Landscape View into Mental and Gastrointestinal Health and Disorders. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14:1717-1763. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Quaglio AEV, Grillo TG, De Oliveira ECS, Di Stasi LC, Sassaki LY. Gut microbiota, inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:4053-4060. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Rebersek M. Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1325. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Ranjbar M, Salehi R, Haghjooy Javanmard S, Rafiee L, Faraji H, Jafarpor S, Ferns GA, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Manian M, Nedaeinia R. The dysbiosis signature of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer-cause or consequences? A systematic review. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:194. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Coker OO, Nakatsu G, Dai RZ, Wu WKK, Wong SH, Ng SC, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Yu J. Enteric fungal microbiota dysbiosis and ecological alterations in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2019;68:654-662. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Dickson I. Fungal dysbiosis associated with colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:76. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Maisonneuve C, Irrazabal T, Martin A, Girardin SE, Philpott DJ. The impact of the gut microbiome on colorectal cancer. Annual Review of Cancer Biology. 2018;2:229-249. [DOI] |

| 25. | McQuade JL, Daniel CR, Helmink BA, Wargo JA. Modulating the microbiome to improve therapeutic response in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:e77-e91. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Dai Z, Coker OO, Nakatsu G, Wu WKK, Zhao L, Chen Z, Chan FKL, Kristiansen K, Sung JJY, Wong SH, Yu J. Multi-cohort analysis of colorectal cancer metagenome identified altered bacteria across populations and universal bacterial markers. Microbiome. 2018;6:70. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Guo S, Li L, Xu B, Li M, Zeng Q, Xiao H, Xue Y, Wu Y, Wang Y, Liu W, Zhang G. A Simple and Novel Fecal Biomarker for Colorectal Cancer: Ratio of Fusobacterium Nucleatum to Probiotics Populations, Based on Their Antagonistic Effect. Clin Chem. 2018;64:1327-1337. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Xie YH, Gao QY, Cai GX, Sun XM, Sun XM, Zou TH, Chen HM, Yu SY, Qiu YW, Gu WQ, Chen XY, Cui Y, Sun D, Liu ZJ, Cai SJ, Xu J, Chen YX, Fang JY. Fecal Clostridium symbiosum for Noninvasive Detection of Early and Advanced Colorectal Cancer: Test and Validation Studies. EBioMedicine. 2017;25:32-40. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Liang Q, Chiu J, Chen Y, Huang Y, Higashimori A, Fang J, Brim H, Ashktorab H, Ng SC, Ng SSM, Zheng S, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Yu J. Fecal Bacteria Act as Novel Biomarkers for Noninvasive Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:2061-2070. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Wong SH, Kwong TNY, Chow TC, Luk AKC, Dai RZW, Nakatsu G, Lam TYT, Zhang L, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Ng SSM, Wong MCS, Ng SC, Wu WKK, Yu J, Sung JJY. Quantitation of faecal Fusobacterium improves faecal immunochemical test in detecting advanced colorectal neoplasia. Gut. 2017;66:1441-1448. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Wu Y, Jiao N, Zhu R, Zhang Y, Wu D, Wang AJ, Fang S, Tao L, Li Y, Cheng S, He X, Lan P, Tian C, Liu NN, Zhu L. Identification of microbial markers across populations in early detection of colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3063. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | Martin-Gallausiaux C, Salesse L, Garcia-Weber D, Marinelli L, Beguet-Crespel F, Brochard V, Le Gléau C, Jamet A, Doré J, Blottière HM, Arrieumerlou C, Lapaque N. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes inflammatory and anti-apoptotic responses in colorectal cancer cells via ADP-heptose release and ALPK1/TIFA axis activation. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2295384. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Wang S, Liu Y, Li J, Zhao L, Yan W, Lin B, Guo X, Wei Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum Acts as a Pro-carcinogenic Bacterium in Colorectal Cancer: From Association to Causality. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:710165. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | McCoy AN, Araújo-Pérez F, Azcárate-Peril A, Yeh JJ, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Fusobacterium is associated with colorectal adenomas. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53653. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Suehiro Y, Zhang Y, Hashimoto S, Takami T, Higaki S, Shindo Y, Suzuki N, Hazama S, Oka M, Nagano H, Sakaida I, Yamasaki T. Highly sensitive faecal DNA testing of TWIST1 methylation in combination with faecal immunochemical test for haemoglobin is a promising marker for detection of colorectal neoplasia. Ann Clin Biochem. 2018;55:59-68. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Xing C, Zhihao L, Ji D. Diagnostic value of fecal Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer. Arch Med Sci. 2023;19:1929-1933. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 38. | Zhang X, Zhu X, Cao Y, Fang JY, Hong J, Chen H. Fecal Fusobacterium nucleatum for the diagnosis of colorectal tumor: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2019;8:480-491. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Mima K, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Cao Y, Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Yang J, Dou R, Masugi Y, Song M, Kostic AD, Giannakis M, Bullman S, Milner DA, Baba H, Giovannucci EL, Garraway LA, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C, Meyerson M, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut. 2016;65:1973-1980. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Chen Y, Lu Y, Ke Y, Li Y. Prognostic impact of the Fusobacterium nucleatum status in colorectal cancers. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17221. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Lee JB, Kim KA, Cho HY, Kim D, Kim WK, Yong D, Lee H, Yoon SS, Han DH, Han YD, Paik S, Jang M, Kim HS, Ahn JB. Association between Fusobacterium nucleatum and patient prognosis in metastatic colon cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11:20263. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, Dutton RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559-563. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 43. | Helmink BA, Khan MAW, Hermann A, Gopalakrishnan V, Wargo JA. The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy. Nat Med. 2019;25:377-388. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 44. | Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, Norat T. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20456. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 45. | Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabaté J, Fan J, Sveen L, Bennett H, Knutsen SF, Beeson WL, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Butler TL, Herring RP, Fraser GE. Vegetarian dietary patterns and the risk of colorectal cancers. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:767-776. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Kerr J, Anderson C, Lippman SM. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, diet, and cancer: an update and emerging new evidence. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e457-e471. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Ishikawa H, Akedo I, Otani T, Suzuki T, Nakamura T, Takeyama I, Ishiguro S, Miyaoka E, Sobue T, Kakizoe T. Randomized trial of dietary fiber and Lactobacillus casei administration for prevention of colorectal tumors. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:762-767. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | Rafter J, Bennett M, Caderni G, Clune Y, Hughes R, Karlsson PC, Klinder A, O'Riordan M, O'Sullivan GC, Pool-Zobel B, Rechkemmer G, Roller M, Rowland I, Salvadori M, Thijs H, Van Loo J, Watzl B, Collins JK. Dietary synbiotics reduce cancer risk factors in polypectomized and colon cancer patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:488-496. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 49. | Chen J, Zhao KN, Vitetta L. Effects of Intestinal Microbial-Elaborated Butyrate on Oncogenic Signaling Pathways. Nutrients. 2019;11. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Yu T, Guo F, Yu Y, Sun T, Ma D, Han J, Qian Y, Kryczek I, Sun D, Nagarsheth N, Chen Y, Chen H, Hong J, Zou W, Fang JY. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell. 2017;170:548-563.e16. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 51. | Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, Daillère R, Fluckiger A, Messaoudene M, Rauber C, Roberti MP, Fidelle M, Flament C, Poirier-Colame V, Opolon P, Klein C, Iribarren K, Mondragón L, Jacquelot N, Qu B, Ferrere G, Clémenson C, Mezquita L, Masip JR, Naltet C, Brosseau S, Kaderbhai C, Richard C, Rizvi H, Levenez F, Galleron N, Quinquis B, Pons N, Ryffel B, Minard-Colin V, Gonin P, Soria JC, Deutsch E, Loriot Y, Ghiringhelli F, Zalcman G, Goldwasser F, Escudier B, Hellmann MD, Eggermont A, Raoult D, Albiges L, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359:91-97. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 52. | D'Haens GR, Jobin C. Fecal Microbial Transplantation for Diseases Beyond Recurrent Clostridium Difficile Infection. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:624-636. [PubMed] [DOI] |