修回日期: 2012-02-16

接受日期: 2012-03-06

在线出版日期: 2012-04-18

目的: 研究臭氧对非酒精性脂肪性肝病(nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD)炎症水平的防治作用及安全性评估.

方法: 24只♂新西兰兔分为3组: 模型组10只, 臭氧组4只, 普拉固加阿司匹林组10只. 实验时间12 wk, 每周称量1次体质量. 超声检测第2周、第5周、第8周及第12周的颈总动脉和腹主动脉内膜-中层厚度(intimal-medial thickness, IMT). 病理观察颈总动脉、主动脉、肝、心及肾脏病理变化. 检测血清生化、血脂、肌酐和尿酸水平. ELISA测定血清8-OHdG、TRX、4-HNE、8-iso-PGF2a、LEP、ADPN、FFA、ET、IL-6、TNF-α、MDA、MCP-1、hs-CRP、NOS、NO、GSH、reduced glutathione、GSH-Px的含量.

结果: 实验动物超声检测内膜增厚, 提示模型成功, 臭氧组体质量明显轻于其他组. 各组主动脉内膜下脂质沉积斑块大小有统计学意义(P = 0.037, P<0.05), 而脂质沉积厚度各组无统计学意义. 臭氧组肝脏气球样变性程度明显轻于模型组和普拉固加阿司匹林组(P = 0.04, P<0.05), 但肝脂肪变性程度3组间无统计学意义. 病理心脏脂质沉积及肾脏肾小管上皮细胞空泡变性程度均无统计学意义. 各组血清生化指标均无统计学差异(P>0.05). 氧化应激、脂质过氧化、炎症水平相关等18个血清细胞因子检测, 与模型组相比, 臭氧组除了ET、8-OHdG、GSH、GSH-Px及FFA无统计学意义, 其余13个因子均有统计学意义(P<0.05), 其中LEP、ADPN、IL-6、TNF-α、MCP-1、hs-CRP、NOS、TRX、MDA、4-HNE、8-iso-PGF2a水平增高, NO、reduced glutathione水平降低, 但普拉固组加阿司匹林组上述所有因子与模型组间均无统计学意义.

结论: 臭氧减轻非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, NASH)炎症的同时可改善颈总动脉、腹主动脉粥样硬化斑块面积的趋势, 未发现臭氧作为抗氧剂对肝脏、肾脏和心脏造成的病理可见损伤. 臭氧全面提高了血清中众多涉及氧化应激、脂质过氧化、炎症细胞因子水平, 其作用机制值得进一步探讨.

引文著录: 陈兰, 朱新生, 桑伟, 希尔娜依·阿不都黑力力, 范晓棠, 何方平. 臭氧对高脂喂养诱导新西兰兔非酒精性脂肪性肝炎的防治作用. 世界华人消化杂志 2012; 20(11): 907-915

Revised: February 16, 2012

Accepted: March 6, 2012

Published online: April 18, 2012

AIM: To assess whether ozone exerts a protective and therapeutic effect on inflammatory injury in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and atherosclerosis in rabbits.

METHODS: Twenty-four male New Zealand rabbits were randomly divided into three groups: model group (n = 10), ozone group (n = 4), and pravastatin plus aspirin group (n = 10). The experimental duration is 12 weeks. Rabbits were weighed once per week. Rabbits of all groups were given a high fat diet, and the ozone group and pravastatin plus aspirin group were additionally given ozone and pravastatin plus aspirin from the second week to the end of the experiment, respectively. The intimal-medial thickness (IMT) of the carotid artery and abdominal aorta was measured by ultrasound at weeks 2, 5, 8 and 12. HE staining was used to examine pathological changes in the carotid artery, aorta, liver, heart and kidney during the formation of NAFLD and AS. The contents of serum TC, LDL, HDL, ALT, γ-GT, Cr and UA were determined. ELISA was used to determine the changes in serum contents of 8-OHdG, TRX, 4-HNE, 8-iso-PGF2a, LEP, ADPN, FFA, ET, IL-6, TNF-α, MDA, MCP-1, hs-CRP, NOS, NO, GSH, reduced glutathione and GSH-Px.

RESULTS: At the end of the experiment, intimal thickening was observed, which suggests that nonalcoholic steatohepatitis was induced successfully. The body weight of rabbits in the ozone group was significantly lower than that in other groups. The percentage of area of aortic lipid deposition in the intima was statistically significant among the three groups (P = 0.037, P < 0.05), but no statistically significant difference was found in the thickness of lipid deposition (P > 0.05). The degree of balloon-like degeneration in the liver differed significantly among the three groups (P < 0.05); however, the degree of hepatic steatosis showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). The degree of lipid deposition in the heart and lipid degeneration of tubular epithelial cells in the kidney showed no statistically significant difference among different groups. Compared to the model group, serum levels of LEP, ADPN, IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1, hs-CRP, NOS, TRX, MDA, 4-HNE and 8-iso-PGF2a significantly increased and those of NO and reduced glutathione content decreased in the ozone group (all P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Ozone reduces inflammatory injury in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and may be useful in preventing atherosclerosis. Ozone as an antioxidant does not cause visible damage to the liver, kidney and heart. Ozone can improve serum levels of inflammatory cytokines which are involved in oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation.

- Citation: Chen L, Zhu XS, Sang W, Xiernayi·Abuduhelili, Fan XT, He FP. Protective and therapeutic effect of ozone on diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in rabbits. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2012; 20(11): 907-915

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v20/i11/907.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v20.i11.907

我国非酒精性脂肪性肝病(nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD)普通人群流行率达12%-18%, 低龄化趋势明显, 目前已经成为一个严重的公共卫生问题. NAFLD对于肝脏本身的危害性已经得到认同, 而与心血管疾病之间的相关性正日益被重视. 如何预防以及阻止NAFLD患者发生动脉硬化具有巨大应用价值. 最新研究表明, 在NAFLD患者中, 内皮依赖的血管扩张受损以及颈动脉内膜中层厚度增加是独立于肥胖症和其他确切危险因素之外的可靠的亚临床动脉粥样硬化指标[1]. NAFLD可导致人体内的脂代谢及慢性炎症持续等方面的异常, 促进及加速动脉粥样硬化的进程. 近年来, 医用臭氧治疗缺血性疾病的有效性和安全性虽然获得肯定, 但主流医学并未接受臭氧作为治疗药物的观点. 研究表明臭氧在肝肾损伤[2-4]、心脏缺血再灌注及移植手术[5,6]、脓毒性休克[7,8]、改善动脉硬化并下肢血栓[9-11]等外周血管阻塞性疾病[12]具有保护作用. 并且, 臭氧在急性脑缺血及视网膜缺血、黄斑变性、病毒性肝炎、慢性感染中也有治疗作用[13]. 本研究通过高脂饮食建立实验性NAFLD兔模型, 以臭氧进行干预, 普拉固加阿司匹林经典药物治疗为对照, 从肝脏炎症水平和动脉粥样硬化程度两方面验证臭氧药用潜力, 并观察臭氧对心脏、肾脏组织学及功能的安全性探讨.

♂纯种新西兰兔子24只, 体质量1.8 kg±0.2 kg, 购自新疆医科大学实验动物中心. 高脂饲料配制为基础饲料85%(新疆维吾尔自治区实验动物医学中心), 猪油8%(市售板油自制), 胆固醇2%(Amresco进口分装), 蛋黄粉5%(Amresco进口分装). 高压臭氧是德国HERRMANN APPARA TEBAU GmbH产生的氧气与臭氧的混合气体, 市售拜耳阿司匹林肠溶片和施贵宝普伐他汀钠片. 血清总胆固醇(total cholesterol, TC)、低密度脂蛋白(low density lipoprotein, LDL)、高密度脂蛋白(high density lipoprotein, HDL)、谷丙转氨酶(alanineaminotransferase, ALT)、γ-谷氨酰氨基转移酶(γ-glutamine-transferase, γ-GT)、肌酐(creatinine, Cr)和尿酸(uric acid, UA)检测试剂盒购自深圳迈瑞生物医疗股份有限公司. 8羟基脱氧鸟苷(8-hydroxy-deoxyguanosine, 8-OHdG)、硫氧还原蛋白(thioredoxin, TRX)、4-羟基壬稀酸(4-hydroxynonenal, 4-HNE)、8-异构前列腺素F2a(8-Iosmerie Porastglnadin-2a, 8-iso-PGF2a)、瘦素(leptin, LEP)、脂联素(adiponectin, ADPN)、游离脂肪酸(free fatty acids, FFA)、内毒素(endotoxin, ET)、白介素6(IL-6)、肿瘤坏死因子α(tumor necrosis factor-α, TNF-α)、丙二醛(malondialdehyde, MDA)、单核细胞趋化蛋白1(monocyte chemotactic protein-1, MCP-1)、超敏C反应蛋白(hypersensitive C-reactive protein, hs-CRP)、一氧化氮合成酶(nitricoxide synthase, NOS)、一氧化氮(nitricoxide, NO)、谷胱甘肽(glutathione, GSH), 还原型谷胱甘肽(reduced glutathione form)及谷胱甘肽过氧化酶(glutathione peroxidase, GSH-Px)的ELISA试剂盒为美国R&D公司进口分装.

1.2.1 分组及干预: 适应性喂养2 wk后随机分为3组, 模型组10只, 臭氧组4只, 普拉固加阿司匹林组10只, 共12 wk. 模型组给予高脂饲料, 臭氧组高脂喂养同时给予臭氧, 第2周开始臭氧经直肠灌注[40 μg/(mL·kg)], 每周2次, 普拉固加阿司匹林组[普拉固5 mg/(kg·d), 阿司匹林12 mg/(kg·d)]高脂喂养同时给予不同干预, 高脂饲料. 整个实验期间由专业饲养员饲养于兔饲养室, 所有实验动物均单笼饲养, 饮水不限.

1.2.2 取材: 实验动物处理及标本收集由专业兽医按规程操作. 心脏采血离心15 min, -80 ℃冰箱保存. 处死动物, 心脏、肝脏右叶、右肾上极约1 cm×1 cm大小各脏器同一部位取材, 10%甲醛溶液固定, 常规病理学HE染色.

1.2.3 观察指标及检测: (1)实验过程中每周称重1次; (2)测量颈总和腹主动脉内膜中层厚度: 各组分别于第2周、第5周、第8周、第12周检测颈总动脉和腹主动脉的内膜-中层厚度(intimal-medial thickness, IMT). 使用多普勒超声诊断仪(SONOS5500型), 由同一超声专业医师盲法检测并记录数值; (3)血清生化: 测定血清TC、LDL、HDL、ALT、γ-GT、Cr、UA的含量. 采集的血液标本送交新疆医科大学第一附属医院医学研究中心实验动物科学研究部盲法完成; (4)组织学: 常规标本处理, HE染色, 观察颈总动脉、主动脉、肝、心及肾脏病理变化. 其中肝细胞脂肪变性分度标准为: 非酒精性脂肪性肝病诊疗指南(2006-02修订); 肝气球样变性分度标准为: 轻度, <30%肝细胞水样变; 中度, 30%-70%肝细胞水样变; 重度, >70%肝细胞气球样变; (5)血清细胞因子检测: 采用ELISA法复孔检测8-OHdG、TRX、4-HNE、8-iso-PGF2a、LEP、ADPN、FFA、ET、IL-6、TNF-α、MDA、MCP-1、hs-CRP、NOS、NO、GSH、reduced glutathione、GSH-Px的含量, 实施盲法并严格按照试剂盒说明书的步骤操作.

统计学处理 所有统计学处理均采用SPSS17.0统计软件包进行. 计量资料采用mean±SD, IMT及体质量采用重复测量的方差分析, 等级资料采用秩和检验, 多组间均数的总体比较方差齐采用单因素方差分析, 不满足方差分析条件时用调整检验水准的秩和检验. 所有数据进行方差齐性检验及正态性检验, 检验水准α = 0.05, 以P<0.05为有统计学意义.

臭氧组体质量显著轻于其他组(表1). 其中分组因素, 模型组与臭氧组(P = 0.026)和臭氧组与普拉固加阿司匹林组(P = 0.007)均有统计学意义(P<0.05), 但普拉固加阿司匹林组和模型组间体质量无统计学意义(P>0.05). 各组的体质量在实验前、4 wk、8 wk、12 wk这4个不同时间点因素上均有统计学意义(P = 0.000, P<0.05).

在第2周、第5周臭氧组颈总动脉IMT低于模型组和普拉固加阿司匹林组(P<0.001). 在第5周和第8周各组颈总动脉IMT无统计学意义, 其他各时间点各组颈总动脉IMT均有统计学意义(P = 0.000, P<0.05). 而腹主动脉IMT除在第8周和第12周各组无统计学意义外, 其余各时间点有统计学意义(P = 0.000, P<0.05, 表2).

| 分组 | n | 部位 | IMT | |||

| 2 wk | 5 wk | 8 wk | 12 wk | |||

| 模型组 | 8 | 颈总动脉 | 203.80±14.08 | 302.50±29.64 | 311.30±9.91 | 282.50±40.62 |

| 腹主动脉 | 310.00±10.69 | 420.00±30.24 | 431.30±28.00 | 387.50±44.00 | ||

| 普拉固加阿司匹林组 | 8 | 颈总动脉 | 203.80±29.73 | 318.80±22.32 | 295.00±22.04 | 277.50±36.15 |

| 腹主动脉 | 301.30±36.43 | 441.30±46.43 | 395.00±37.03 | 405.00±51.55 | ||

| 臭氧组 | 4 | 颈总动脉 | 212.50±29.86 | 292.50±22.17 | 317.50±15.00 | 260.00±27.08 |

| 腹主动脉 | 337.50±1500.00 | 445.00±43.59 | 397.50±26.30 | 370.00±53.54 | ||

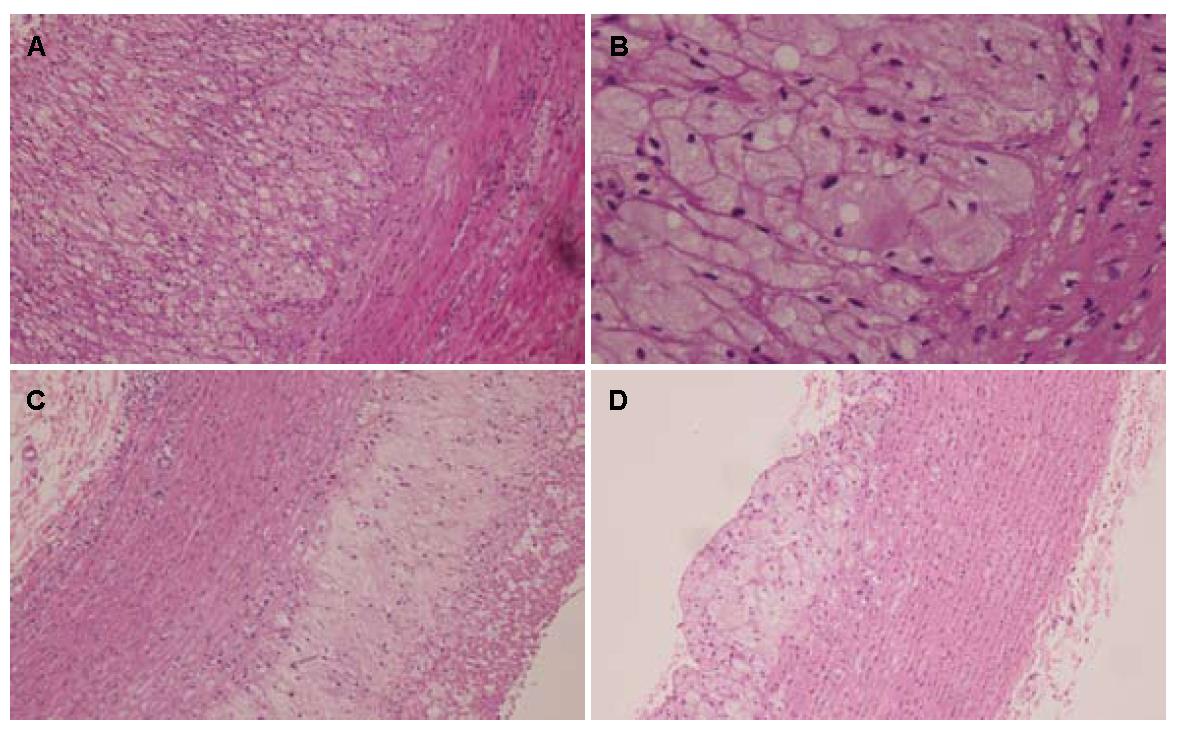

2.3.1 主动脉壁厚度: 各组血管壁厚度有统计学意义(P = 0.012), 臭氧组血管壁厚度和中膜厚度均高于模型组和普拉固加阿司匹林组(P<0.017), 相对于模型组和普拉固加阿司匹林组, 各组脂质斑块脂质沉积百分比有统计学意义(P = 0.037, P<0.05), 臭氧组脂质斑块脂质沉积占管腔大小的百分比显著性减少(P<0.05, 图1, 表3).

| 分组 | n | 管壁厚度(μm) | 中膜厚度(μm) | 内膜下脂质沉积厚度(μm) | 脂质沉积占管腔大小的百分比(%) | |||

| <30 | 30-50 | 50-75 | 75-100 | |||||

| 模型组 | 8 | 2.56±0.26 | 1.47±0.35 | 3.61±0.99 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 普拉固加阿司匹林组 | 8 | 2.81±0.29 | 1.36±0.50 | 2.77±0.85 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 臭氧组 | 4 | 3.73±0.69 | 2.44±0.18 | 3.25±1.87 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

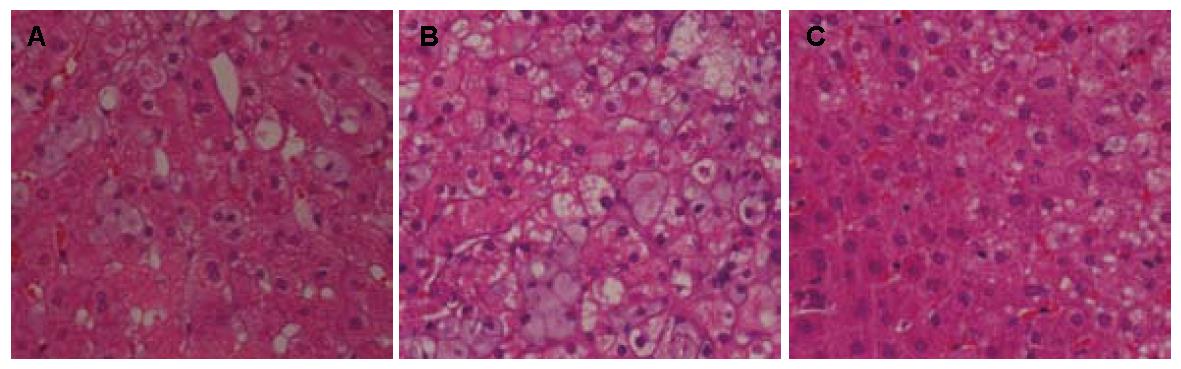

2.3.2 肝脏: 臭氧组肝细胞脂肪样变性分级在F0-F2之间, 1例达F4, 脂滴大小不均一, 以小脂滴为主, 肝细胞气球样变性低于30%有3例. 普拉固加阿司匹林组肉眼观肝细胞脂肪样变分级在F2-F4之间, 4例达F4, 6例超过70%肝细胞重度气球样变性. 各组肝脂肪变性程度间无统计学意义(P = 0.185, P>0.05), 臭氧组气球样变性程度均轻于模型组和普拉固加阿司匹林组(P = 0.04, P<0.05, 图2, 表4).

| 分组 | n | 脂肪变性 | P值 | 气球样变性 | P值 | ||||||

| F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | 轻度<30% | 中度30%-50% | 重度>75% | ||||

| 模型组 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.185 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0.040 |

| 普拉固加阿司匹林组 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 | ||

| 臭氧组 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | ||

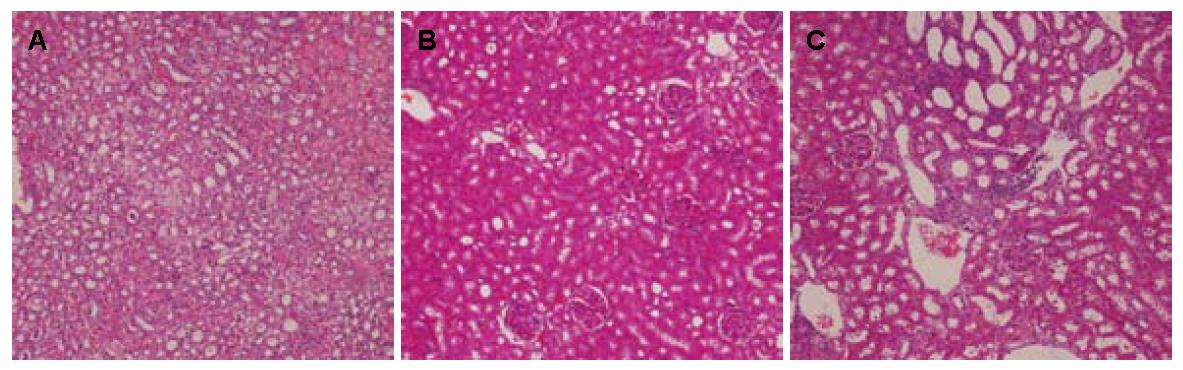

2.3.3 肾脏: 肉眼观各组肾脏大体无明显异常, 各组肾小管上皮细胞空泡变性程度无统计学意义(P>0.05, 图3, 表5).

| 分组 | n | 0% | 5% | 5%-30% | 30%-50% | 50%-75% | >75% |

| 模型组 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 臭氧组 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 普拉固加阿司匹林组 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

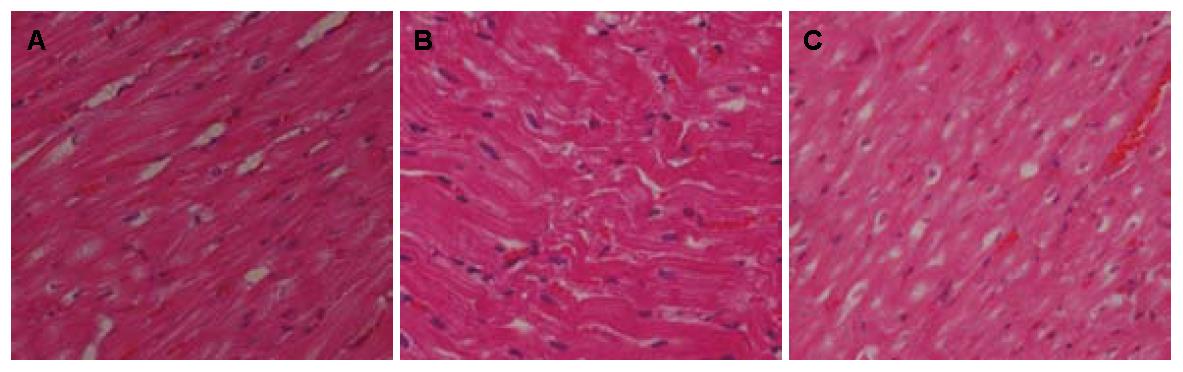

2.3.4 心脏: 各组心脏病理HE染色见图4. 经统计分析, 各组心脏脂质沉积例数无统计学意义(P = 0.580). 各组心脏脂质沉积占管腔大小的百分比及厚度均无统计学意义(P>0.05, 图4, 表6).

| 分组 | n | 无沉积 | 有沉积 | |||||

| 小计 | 脂质沉积占管腔大小的百分比 | 脂质沉积厚度 | ||||||

| <30% | 30%-50% | 50%-75% | 75%-100% | |||||

| 模型组 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.400±0.170 |

| 臭氧组 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0.661±0.150 |

| 普拉固加阿司匹林组 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.300±0.200 |

模型组和臭氧组血清呈不同程度乳白色浑浊. 各组血清TC、LDL及HDL-C含量, 肝功能的指标ALT和γ-GT, 肾功能的指标Cr和UA均无统计学意义(P>0.05, 表7).

| 指标 | 模型组(n = 8) | 臭氧组(n = 4) | 普拉固加阿司匹林组(n = 8) |

| TC | 52.74±10.98 | 46.00±19.43 | 55.67±17.14 |

| HDL | 4.52±1.57 | 4.19±1.15 | 5.11±1.45 |

| LDL | 32.39±8.20 | 30.19±10.14 | 33.74±8.49 |

| ALT | 49.13±35.90 | 49.70±19.79 | 49.97±29.49 |

| r-GT | 40.03±18.93 | 40.97±26.94 | 49.89±20.48 |

| Cr | 202.21±83.44 | 130.30±45.19 | 274.52±224.59 |

| UA | 575.69±492.13 | 541.63±863.54 | 651.67±742.02 |

与模型组相比, 臭氧显著提高了LEP、ADPN、IL-6、TNF-α、MCP-1、hs-CRP、NOS、TRX、MDA、4-HNE、8-iso-PGF2a水平, 降低了NO、还原型谷胱甘肽含量(P<0.05); 但对ET、8-OHdG、GSH、GSH-Px及FFA含量无影响, 统计学无意义(表8).

| 分类 | 因子 | 模型组(n = 8) | 臭氧组(n = 4) | 普拉固加阿司匹林组(n = 8) |

| DNA氧化损伤标志物 | 8-OHdG(μg/L) | 21.34±2.89 | 26.02±2.17 | 20.36±4.85 |

| 脂质氧化代谢产物 | 4-HNE(μmol/L) | 17.90±2.60 | 21.54±1.02a | 17.33±2.74c |

| 8-iso-PGF2a | 60.88±7.03 | 84.41±7.90a | 59.61±14.75c | |

| MDA(nmol/L) | 4.49±0.67 | 6.56±0.42a | 4.47±1.18c | |

| 脂代谢相关因子 | LEP(μg/L) | 7.68±0.98 | 9.92±0.56a | 7.21±1.47c |

| ADPN(ng/L) | 433.81±71.37 | 306.00±29.16a | 430.25±60.95c | |

| FFA(μmol/L) | 692.94±101.18 | 825.00±48.74 | 626.50±124.19c | |

| 炎症因子 | IL-6(ng/L) | 58.78±7.62 | 78.99±6.08a | 54.25±12.70c |

| ET (Eu/mL) | 33.17±8.12 | 42.95±4.69 | 31.96±11.61 | |

| TNF-α(ng/L) | 104.83±17.69 | 146.29±10.34a | 100.61±25.06c | |

| MCP-1(ng/L) | 37.06±4.72 | 51.67±1.50a | 36.33±6.57c | |

| hs-CRP(mg/L) | 7.36±1.97 | 10.33±1.21a | 6.67±2.13c | |

| 氧化应激因子 | NO(μmol/L) | 59.07±10.53 | 37.70±2.35a | 69.11±18.92c |

| NOS(U/mL) | 17.83±3.40 | 23.59±2.48a | 17.36±4.06c | |

| GSH(mg/L) | 195.95±47.83 | 148.18±33.82 | 210.08±48.09 | |

| 还原型GSH(mg/L) | 108.01±18.93 | 76.40±9.24a | 110.21±21.75c | |

| GSH-Px(U/L) | 75.55±13.11 | 59.09±6.26 | 74.17±17.06 | |

| TRX(ng/L) | 209.89±37.35 | 262.02±16.73a | 195.50±46.89c |

NAFLD是目前全世界范围内高流行肝脏疾病, NAFLD肝内慢性炎症促进动脉粥样硬化发生发展, 与快速进展型动脉粥样硬化密切相关. Fan等[14-16]学者认为代谢性疾病尤其NAFLD的危险因素、流行病学及预后等与代谢综合征密切相关. 目前, 研究证实NAFLD与血管内皮损伤、颈动脉IMT和颈动脉斑块形成相关[17-19], 是动脉粥样硬化的一个早期标志[20]. 临床尚无治疗NAFLD的有效药物.

动脉粥样硬化发生机制在于脂质沉积刺激脂肪酸氧化, 产生大量活性氧簇, 氧化应激失衡, 启动慢性不可控炎症损伤, 发生内皮慢性损伤. 这种损伤与高血压、高胆固醇血症、高血脂、糖尿病、吸烟、免疫复合物及感染等致病因素相关, 常见于动脉分叉处或弯曲部位, 内皮损伤的后果是LDL和单核细胞在损伤部位的沉积.

临床上现有的有效阻断动脉粥样硬化的经典药物是他汀类联合阿司匹林[21], 但也仅对30%患者有效, 从动脉粥样硬化致病机制而言, 抗氧化剂的作用更值得推崇, 而临床并不具有循证医学证据的抗氧化药物可用.

本研究中模型组主动脉弓部位内膜下脂质沉积, 同时其肝细胞广泛脂肪性变伴大量气球样改变. 表明高脂饮食诱导动脉粥样硬化伴肝脏达到NASH阶段, 模型成功. 各组主动脉内膜下脂质沉积大小百分比有统计学意义(P<0.05), 而脂质沉积厚度无统计学意义. 研究者发现超声能准确测量动脉IMT, 且动脉粥样硬化时IMT的改变早于斑块的发生[22,23]. 超声检测兔颈总动脉及腹主动脉结果显示, IMT各组无差异, 仅在不同时间点有差异, 在第5周臭氧组颈总动脉IMT低于模型组和普拉固加阿司匹林组. 这提示随着病程的进展, 内膜损伤加重, IMT不断增厚. 并且, 臭氧组并未减少高脂饮食投喂量, 但臭氧组体质量却轻于模型组. 这可能与该组的瘦素水平明显高于其他两组有关, 而且, 该瘦素具有生理活性的可能性较大.

有关医用臭氧安全性研究报告比较多[24-27], 我们对肾脏、心脏的组织形态学改变以及肝肾功能的检测, 未发现臭氧治疗组组织学和生化水平的损伤证据. 该结果与Guanche等[28]研究结果一致, 甚至具有与普拉固加阿司匹林经典药物相同的安全性. Di Filippo等[29]研究也显示臭氧可保护急性心肌梗塞. 上述研究结果表明, 臭氧减轻NAFLD的炎症, 同时并未加重颈总动脉、腹主动脉IMT及相关动脉粥样硬化的进程.

在本研究中我们对臭氧作用机制做了细胞因子水平的初步探讨, 双盲法筛查了各组血清DNA氧化应激损伤标志物、脂质氧化代谢产物、脂质代谢相关的因子、炎症因子、氧化应激时体内氧化还原水平状态. 结果显示臭氧全面提升了总体的氧化应激、脂质过氧化水平, 炎症水平. Bocci等[13]发现臭氧可以提高内皮细胞NO合成能力, 我们的研究显示NOS水平增加, 与Bocci观点一致, 但并未提高血清NO水平, 考虑与其消耗过多有关; 此外, 血清瘦素水平增加, 可能是臭氧同时减轻NAFLD的炎症损伤和动脉粥样硬化的另一个机制, 脂肪组织是瘦素分泌和作用的载体, 其分泌水平与NAFLD的发病密切相关, 生理性瘦素水平的增加可以通过抑制食欲、减少摄食、启动能量消耗和减轻体质量, 从而降低NAFLD病例的肝脂水平[30,31]; 同时, 胰岛素抵抗状态发生瘦素抵抗, 瘦素抵抗加重胰岛素抵抗. 本研究首次发现NAFLD炎症改善, 瘦素水平增加同时伴有兔体质量明显减轻, 这一系列结果提示臭氧干预组瘦素生理活性是增加的, 进一步研究明确臭氧是否改善瘦素抵抗是必要的.

该实验也存在缺陷, 臭氧剂量可能过大, 造成血液抗氧化系统物质被消耗过度. 这从NO、reduced glutathione form消耗过多可以显示; 另外, 兔的抗氧化系统与人体水平完全不同, 按照常规药物剂量转化公式折算方法, 并不适用于臭氧. 但检测结果臭氧未加重动脉粥样硬化及炎症. 臭氧是目前唯一发现会影响血清氧化应激细胞因子水平的"药物", 臭氧改善肝脏组织学及动脉粥样硬化的机制, 目前仍不清楚其机制. 他与他汀类等经典药物作用机制不同. 这可能意味着一种新的治疗模式.

总之, 本研究主要进行了病理形态学及细胞因子氧化应激等结果的描述性报道, 原因在于该发现具有潜在的巨大的临床实用价值和意义. 尽管我们实验有很多不足之处, 本实验提示我们今后进一步探讨臭氧对NAFLD炎症阻断机制是非常必要的.

非酒精性脂肪肝病(nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD)与动脉粥样硬化进展的相关性是目前国际研究热点领域, 但临床缺乏有效干预手段.

高泽立, 副教授, 周浦医院消化科, 上海交大医学院九院周浦分院

NAFLD对于肝脏本身的危害性已经得到认同, 而与心血管疾病之间的相关性正日益被重视. 如何预防以及阻止NAFLD患者发生动脉硬化具有巨大应用价值.

最新研究表明, 在NAFLD患者中, 内皮依赖的血管扩张受损以及颈动脉内膜中层厚度增加是独立于肥胖症和其他确切的危险因素之外的可靠的亚临床动脉粥样硬化指标.

基于医用臭氧作用机制和代谢性慢性炎症发病机制而在肝脏炎症阻断方面进行该项原创性探索, 具有明确的应用前景.

本实验紧扣当前脂肪肝研究热点,从动物模型建立到组织学形态观察,从肝功能到细胞因子水平, 全面观察了臭氧对高脂喂养诱导新西兰兔NAFLD的作用, 具有较好的指导意义和参考价值.

编辑: 张姗姗 电编: 鲁亚静

| 1. | Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1341-1350. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Chen H, Xing B, Liu X, Zhan B, Zhou J, Zhu H, Chen Z. Ozone oxidative preconditioning inhibits inflammation and apoptosis in a rat model of renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;581:306-314. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Ajamieh H, Merino N, Candelario-Jalil E, Menéndez S, Martinez-Sanchez G, Re L, Giuliani A, Leon OS. Similar protective effect of ischaemic and ozone oxidative preconditionings in liver ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Pharmacol Res. 2002;45:333-339. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Ajamieh HH, Menéndez S, Martínez-Sánchez G, Candelario-Jalil E, Re L, Giuliani A, Fernández OS. Effects of ozone oxidative preconditioning on nitric oxide generation and cellular redox balance in a rat model of hepatic ischaemia-reperfusion. Liver Int. 2004;24:55-62. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Peralta C, Closa D, Xaus C, Gelpí E, Roselló-Catafau J, Hotter G. Hepatic preconditioning in rats is defined by a balance of adenosine and xanthine. Hepatology. 1998;28:768-773. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Peralta C, Xaus C, Bartrons R, Leon OS, Gelpi E, Roselló-Catafau J. Effect of ozone treatment on reactive oxygen species and adenosine production during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion. Free Radic Res. 2000;33:595-605. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Zamora ZB, Borrego A, López OY, Delgado R, González R, Menéndez S, Hernández F, Schulz S. Effects of ozone oxidative preconditioning on TNF-alpha release and antioxidant-prooxidant intracellular balance in mice during endotoxic shock. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:16-22. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Torossian A, Ruehlmann S, Eberhart L, Middeke M, Wulf H, Bauhofer A. Inflamm Res. 2004;53 Suppl 2:S122-S125. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Hernandez. Intravenous ozone therapy on patients with heart disease to reduce blood cholesterol and anti-oxidation reaction stimulus. FreeRadical Biology&Medicine. 1995;115-119. |

| 10. | Tylicki L, Biedunkiewicz B, Nieweglowski T, Chamienia A, Slizien AD, Luty J, Lysiak-Szydlowska W, Rutkowski B. Ozonated autohemotherapy in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: influence on lipid profile and endothelium. Artif Organs. 2004;28:234-237. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Wentworth P, Nieva J, Takeuchi C, Galve R, Wentworth AD, Dilley RB, DeLaria GA, Saven A, Babior BM, Janda KD. Evidence for ozone formation in human atherosclerotic arteries. Science. 2003;302:1053-1056. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Giunta R, Coppola A, Luongo C, Sammartino A, Guastafierro S, Grassia A, Giunta L, Mascolo L, Tirelli A, Coppola L. Ozonized autohemotransfusion improves hemorheological parameters and oxygen delivery to tissues in patients with peripheral occlusive arterial disease. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:745-748. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Bocci V, Di Paolo N. Oxygen-ozone therapy in medicine: an update. Blood Purif. 2009;28:373-376. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Fan JG, Saibara T, Chitturi S, Kim BI, Sung JJ, Chutaputti A. What are the risk factors and settings for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia-Pacific? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:794-800. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Fan JG, Farrell GC. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Hepatol. 2009;50:204-210. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Fan JG, Li F, Cai XB, Peng YD, Ao QH, Gao Y. Effects of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on the development of metabolic disorders. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1086-1091. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Fracanzani AL, Burdick L, Rasselli S, Pedotti P, Grigore L, Santorelli G, Valenti L, Maraschi A, Catapano A, Fargion S. 89 Risk of early atherosclerosis evaluated by carotid artery intima-media thickness in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a case control study. Hepatology. 2005;44:S39-S40. |

| 18. | Villanova N, Moscatiello S, Ramilli S, Bugianesi E, Magalotti D, Vanni E, Zoli M, Marchesini G. Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular risk profile in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:473-480. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Volzke H, Robinson DM, Kleine V, Deutscher R, Hoffmann W, Ludemann J, Schminke U, Kessler C, John U. Hepatic steatosis is associated with an increased risk of carotid atherosclerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1848-1853. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109:III27-III32. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P, Meade T. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849-1860. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Pignoli P, Tremoli E, Poli A, Oreste P, Paoletti R. Intimal plus medial thickness of the arterial wall: a direct measurement with ultrasound imaging. Circulation. 1986;74:1399-1406. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Wong M, Edelstein J, Wollman J, Bond MG. Ultrasonic-pathological comparison of the human arterial wall. Verification of intima-media thickness. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:482-486. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Ripamonti CI, Cislaghi E, Mariani L, Maniezzo M. Efficacy and safety of medical ozone (O(3)) delivered in oil suspension applications for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with bone metastases treated with bisphosphonates: Preliminary results of a phase I-II study. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:185-190. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Steppan J, Meaders T, Muto M, Murphy KJ. A metaanalysis of the effectiveness and safety of ozone treatments for herniated lumbar discs. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:534-548. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Ragab A, Shreef E, Behiry E, Zalat S, Noaman M. Randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of ozone therapy as treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:54-60. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Anonymous. Safety of Ozone for Dental Therapy Established. Biological Therapies in Dentistry. 2005;S4. |

| 28. | Guanche D, Zamora Z, Hernández F, Mena K, Alonso Y, Roda M, Gonzáles M, Gonzales R. Effect of ozone/oxygen mixture on systemic oxidative stress and organic damage. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2010;20:25-30. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Di Filippo C, Luongo M, Marfella R, Ferraraccio F, Lettieri B, Capuano A, Rossi F, D'Amico M. Oxygen/ozone protects the heart from acute myocardial infarction through local increase of eNOS activity and endothelial progenitor cells recruitment. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;382:287-291. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Bartek J, Bartos J, Galuska J, Galusková D, Stejskal D, Ivo K, Ehrmann J, Ehrman J, Chlup R. Expression of ob gene coding the production of the hormone leptin in hepatocytes of liver with steatosis. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2001;145:15-20. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Petersen KF, Oral EA, Dufour S, Befroy D, Ariyan C, Yu C, Cline GW, DePaoli AM, Taylor SI, Gorden P. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1345-1350. [PubMed] [DOI] |