Published online Sep 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i9.2109

Revised: August 23, 2002

Accepted: October 18, 2002

Published online: September 15, 2003

AIM: To determine the efficacy and long-term outcome of biofeedback treatment for chronic idiopathic constipation and to compare the efficacy of two modes of biofeedback (EMG-based and manometry-based biofeedback).

METHODS: Fifty consecutive contactable patients included 8 cases of slow transit constipation, 36 cases of anorectic outlet obstruction and 6 cases of mixed constipation. Two modes of biofeedback were used for these 50 patients, 30 of whom had EMG-based biofeedback, and 20 had manometry-based biofeedback. Before treatment, a consultation and physical examination were done for all the patients, related information such as bowel function and gut transit time was documented, psychological test (symptom checklist 90, SCL90) and anorectic physiological test and defecography were applied. After biofeedback management, all the patients were followed up. The Student’s t-test, chi-squared test and Logistic regression were used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS: The period of following up ranged from 12 to 24 months (Median 18 months). 70% of patients felt that biofeedback was helpful, and 62.5% of patients with constipation were improved. Clinical manifestations including straining, abdominal pain, bloating, were relieved, and less oral laxative was used. Spontaneous bowel frequency and psychological state were improved significantly after treatment. Patients with slow and normal transit, and those with and without paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter on straining, benefited equally from the treatment. The psychological status rather than anorectal test could predict outcome. The efficacy of the two modes of biofeedback was similar without side effects.

CONCLUSION: This study suggests that biofeedback has a long-term effect with no side effects, for the majority of patients with chronic idiopathic constipation unresponsive to traditional treatment. Pelvic floor abnormalities and transit time should not be the selection criteria for treatment.

- Citation: Wang J, Luo MH, Qi QH, Dong ZL. Prospective study of biofeedback retraining in patients with chronic idiopathic functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(9): 2109-2113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i9/2109.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i9.2109

Chronic constipation is a common and distressing complaint, which may be secondary to many diseases, or may also be of functional origin. In the United Stats, it is more common in blacks (17%), women (18%), elderly over 60 years (23%), and in those who are inactive, low income, or poorly educated[1]. In Tianjin, China, 4.43% of the general population had this complaint according to a study in 1994.

Chronic idiopathic functional constipation is a severe type of constipation and has poor response to the traditional management. Many such patients could not live without the use of laxatives, suppositories or enemas and experience major physical, social, and psychological impairments from the condition.

Biofeedback has been used for a long time to strengthen pelvic floor muscles in patients with fecal incontinence[2]. In recent years, biofeedback has been used for retraining of the pelvic floor with paradoxical sphincter contraction[3]. The reported results varied and the successful rate ranged from 0 to over 90%[5,6]. Although most groups restricted the use of biofeedback to patients with normal transit and paradoxical pelvic floor contraction during straining[6-9], the technique has a wide therapeutic benefit.

Behavioral techniques were applied to patients with three kinds of constipation (pelvic floor dysfunction, slow transit, and mixed) in order to assess prospectively the effects of biofeedback, to evaluate factors that might be helpful in selecting patients or the optimal method of biofeedback, and to explore the mechanism of this treatment.

From October 1998 to October 1999, 50 patients with chronic idiopathic functional constipation from Tianjin Binjiang hospital and Tianjin Medical University Hospital were offered biofeedback. The duration of constipation of the patients was more than 2 years. All the 50 patients failed to respond to first-line therapy, including dietary advice, bulk-forming agents, and use of laxatives. Operation was performed on 4 patients. There were 36 females and 14 males, their mean age was 52.6 years (range, 16-71), mean duration of constipation was 4.6 years (range, 2.5-30). Detailed information is shown in Table 1.

| No. of cases | 50 (36, female) |

| Average age | 52.6 (10-71) years |

| Average history | 4.6 (2.5-30) years |

| Average onset age | 34 (1-60) years |

| Complaint in childhood | 4 |

| Average follow-up period | 18 (12-28) months |

| Times of biofeedback treatment | 1 |

| Failed treatment prior to BF | |

| Normal traditional conservative treatment | 50 |

| Operation | 4 |

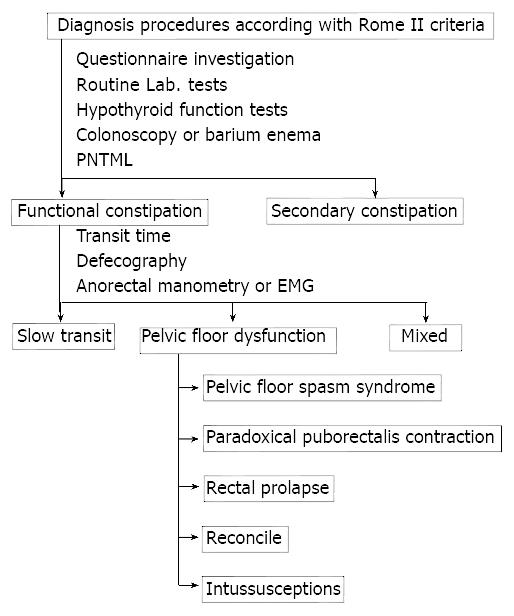

All the patients had constipation as defined by the Rome II criteria, complaining of either decreased bowel frequency (less than three times per week), a sensation of incomplete emptying or a history of difficult evacuation on at least a quarter of occasions, or a need to strain. According to the criteria, we divided the patients into pelvic floor dysfunction (n = 36), slow transit (n = 8) and mixed (n = 6). The algorithm for clinical approach in this study is showed in Figure 1.

Physical examination and thyroid function test were done to exclude constipation secondary to other causes. Moreover, an initial series of tests, including colonoscopy or barium enema failed to detect organic lesions in all patients. Patients were assessed clinically using a specially designed questionnaire that was filled out by a specialist, physician or a medically qualified researcher. The questionnaire included history of age at onset, bowel frequency, precipitation factors, use of laxatives, major and secondary syndromes, family history, urinary syndromes, gynecologic history, and other relevant diseases. A series of tests of colonic and pelvic floor functions were performed before and after biofeedback treatment as described below.

Whole gut transit study We used the method previously reported[10]. Patients ingested twenty radiologically distinguishable radio-opaque markers on day one, and no laxatives or enemas were allowed for five days. In women, the investigation was performed in the nonmenstrual phase. A single plain abdominal radiograph was taken 120 h after ingesting of the markers. We interpreted more than 8(> 40 percent) markers left in the colon as abnormal, which were divided into two kinds: slow transit of whole colon, slow transit of sigmoid colon and rectum.

Anorectal manometry We used an open-tip perfused catheter system (Medtronic Synectics Ltd). The catheter had a four-channel flexible probe with an outside diameter of 4.8 mm. Rectal sensory function to distension was assessed using an intrarectal balloon, according to previously published techniques. The initial sense, a sense of urgency, and the maximum tolerated volume were recorded. Rectal sensation to an electrical stimulus was also assessed using a bipolar electrode placed in the rectum 6 cm above the upper limit of the anal canal. The length of the anal canal was also measured. This technique had been previously validated. Manometric studies were performed with the patient lying on the left side.

Electromyography of the external sphincter muscle We used surface EMG electrode to measure the electromyographic activity of the anal sphincter as described by Abdullhakim and Gerger. The study was performed with the patient in the right lateral position. We repeatedly assessed the myoelectric activity during resting, squeezing, and straining. A reproducible increase in myoelectrical activity during straining was considered as the paradoxical puborectalis contraction.

Defecography Cinedefecography was a dynamic study of anorectal function, and was described before. Evacuation was started from the beginning of straining to completion of rectal emptying, and measured in seconds on a video counter. Subjective evaluation of rectal emptying was then undertaken to determine completeness and speed of evacuation. Prolonged (> 35 s) emptying or incomplete emptying or both were considered as abnormal pelvic floor function. A rectocele that failed to empty the evacuation was considered as significant pelvic floor dysfunction. Paradoxical puborectalis contraction, rectal prolapse and intussusception were diagnosed with defecography.

Psychological questionnaire Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) was used to evaluate the psychological state of patients[11]. Nine factors could be described, which were somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, photic anxiety, padanoid ideation and psychoticism. We could also get the general symptomatic index.

Telephone interview Each patient was interviewed over telephone by an investigator who had not been the patient’s biofeedback therapist. Data were obtained using a questionnaire containing the same questions as those before treatment. Using these pretreatment and post-treatment data, an assessment was made regarding the age of constipation onset of the patient, and whether there were any precipitating factors, including vaginal delivery, hysterectomy, or other surgery. Bowel function before and after biofeedback, and at the time of interview was assessed, including use of bowel evacuants (oral laxatives, enemas, and suppositories), bowel frequency without laxatives, need of strain, need of dig with finger, and a sense of incomplete evacuation. Enquiries were also made about the presence and subjective severity of abdominal pain or bloating. To establish the possible subjective benefits of the treatment as a whole, in addition to the effect on constipation, benefit of biofeedback, improvement of constipation and compliance with practice of biofeedback techniques were asked.

Questionaire A special questionaire including listing symptoms and daily use of laxatives or enemas during and after treatment was designed, and was filled out by patients and was checked by doctors in charge.

Biofeedback therapy Patients were subjected to biofeedback twice per week for five sessions. All the patients were treated as outpatients. At the first session, the anatomy and physiology of the gut and the pelvic floor were explained to the patients using diagrams and their own tests results. The objectives of biofeedback therapy were carefully explained to the patients.

In the pressure-based training, we used the same four-lumen catheter as described above. The side holes were placed in the distal rectum and the anal canal, and the balloon attached to the tip of the catheter was used for training expulsion. During training, the catheter was inserted in the same way as during diagnostic studies, and the subjects were allowed to view the manometric recordings. They were instructed to look for changes in the pressure tracing, thereby visualizing the location and function of the pelvic floor muscles, with specific attention to the responses of the anal sphincter during squeezing and straining. Patients were told that the sphincter should relax during expulsion of the rectal balloon at the urge threshold, indicated by a decrease in basal pressure, and they should learn how to relax the pelvic floor muscles and to push down slowly using their abdominal muscles. Straining and relaxing were repeated until a normal pattern of expulsion occurred. The exercise was repeated several times during an one-hour session.

For EMG feedback, the subjects were seated on a toilet-like chair. Disposable bilateral prenatal surface EMG electrodes were connected to the EMG recording device, which provided auditory and visual signals to aid the patient in observing muscle activity. Resting EMG was noted, then the subject recorded a squeeze, bore down as defecation and tried to relax the pelvic floor and to lower the straining records below the resting recording. Afterward, the patients were trained to expel the rectal balloon connected to a catheter on lateral position and were instructed to pratise expulsion of rectal contents and relax without straining at home.

Polygraf ID (Medtronic Synetics Ltd) was used in this study. The patients were consulted on normal defecography behavior and bowel habits, such as adjusting the number of visits to the toilet, amount of time spent, and posture in toilet. At each biofeedback session the therapist tried to have a good understanding and collaboration with patients. An attempt was made to get patients off laxatives, enemas, and suppositories. When the course of biofeedback was completed, the patients were encouraged to continue practicing the techniques.

Prognostic factors To determine whether certain patient characteristics may predict a response to biofeedback treatment, the patients who benefited from biofeedback were compared with those who did not. Parameters used for comparison were the objective findings of slow or normal transit, the presence or absence of pelvic floor paradoxical contraction on straining, the presence of previous psychological factors, and the compliance of practice the biofeedback at home after the treatment. Difference between EMG-based and Manometry-based biofeedback was compared.

Assessment of symptoms A questionnaire was used to assess the manifestation of patients, it detailed the number of bowel movements, failed attempts of bowel movement, the use of laxatives and enemas, presence of bloating, severity of abdominal pain (0 = no pain, 1 = mild pain, 2 = moderate pain, 3 = severe pain) for each day during one week. The score of one-week abdominal pain was calculated as the sum of seven consecutive daily scores of pain severity.

Patients were investigated with anorectal manometry, EMG, and the one-week bowel habit questionnaire before and after biofeedback retraining. After treatment and 6 months following treatment, a global assessment for the treatment was evaluated by patients through filling the questionnaire, including the degree of improvement of bowel movement.

Statistical methods Non-normal data were expressed as median and full range. Normal data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test was used to compare the treatment results, and the chi-square test was used for comparison of proportions. Prognostic factors were analyzed by logistic regression.

All the 50 patients agreed to participate in the study. Table 1 shows characteristics of the patients. The vast majority of patients were female. Each patient had only one course of biofeedback. Almost 10% of the patients had experienced constipation since childhood. Almost all the patients believed they could not identify a precipitating factor of their constipation. One fifth of patients were recorded as having possible relevant psychological factors.

The median time of follow up was 18 months (12-28 months).

At the end of treatment, 31 of the 50 patients reported a subjectively overall improvement. The overall successful rate was 62%, the successful rate was 72.2% for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction constipation.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of symptoms in the study group. The most common findings were difficult evacuation, hard stools, distention or bloating and laxative dependence.

| Types | n | Successful rate (%) |

| Slow transit | 8 | 3 |

| Pelvic floor dysfunction | 36 | 26 (72.2%) |

| Paradoxical puborectalis contraction | 20 | 16 (80%) |

| Pelvic floor spasm syndrome | 9 | 6 (66.7%) |

| Intussusception | 7 | 4 (55.6%) |

| Mixed | 6 | 2 |

All the patients underwent both a transit study and physiological study, 8 had slow colonic transit, 36 showed pelvic floor dysfunction constipation, 6 had both slow transit and pelvic floor dysfunction (Table 3).

| Symptoms | No. of patients before BF | No. of patients 10 days after BF | No. of patients 1 year after BF |

| Difficult evacuation | 50 | 16a | 13a |

| Hard stools | 40 | 18b | 16b |

| Loose stools at onset of abd. Pain | 39 | 19 (NS) | 22 (NS) |

| No sense of defecate in 1 week | 35 | 20 (NS) | 16 (NS) |

| Need for digitations | 21 | 11 (NS) | 11 (NS) |

| Sense of incomplete emptying | 31 | 18 (NS) | 16 (NS) |

| Distention or bloating | 42 | 15b | 13b |

| Laxative dependence | 48 | 12 (P < 0.01) | 14a |

| Need of enema | 31 | 9b | 9b |

| Perianal pain at defecation | 30 | 16 (NS) | 11 (NS) |

Two methods of biofeedback were applied in this study. We used EMG-based biofeedback for 30 patients, and manometry-based biofeedback for 20 patients.

At the end of treatment, 31 of 50 patients reported a subjectively overall improvement in their symptoms. The need for enema, difficult evacuation, hard stools, distention or bloating and use of laxatives were all significantly improved immediately after biofeedback or after a long-term follow up (Table 2). The proportion of patients with loose stools at onset of pain, no feeling to defecate, need for digitations, feeling of incomplete emptying and perianal pain at defecation were also reduced, but these did not reach statistical significance, probably due to the small number of patients with these symptoms.

Whole gut transit Before biofeedback: 14 of 50 constipated patients were identified as having slow transit. Of them, seven had marker retention predominantly in the rectosigmoid as defined by more than half of the excessively retained markers present in the rectosigmoid, the remaining 7 patients with slow transit had excessive marker retention throughout the colon.

After biofeedback: 5 of 14 slow transit constipation patients reported subjective improvement after biofeedback. 26 of 36 patients with normal transit reported a similar improvement. The difference between the two groups was not significant. Similarly, there was no difference between patients with slow and normal transit.

Among the 7 patients with slow transit, 3 patients with only rectosigmoid delay and 2 with slow transit were due to a more generalized holding up of markers, and reported a subjective improvement.

Defecography Before biofeedback: 42 of 50 constipated patients were identified as having pelvic floor dysfunction constipation. Of them, 22 were complicated with paradoxical puborectalis contraction, 7 with pelvic floor spasm syndrome, 9 with major intussusception.

After biofeedback: 28 of 42 patients reported a subjective improvement after biofeedback. Among them, 15 were complicated with paradoxical puborectalis contraction predominantly, 8 with pelvic floor spasm syndrome and 5 with intussusception. The difference in outcome between the three groups was not significant.

Anorectal manometry There were significant reductions in the index of “initial sense” and “average rest pressure” before and after biofeedback. On the other hand, there was no difference in other results concerning the type of biofeedback (Table 4).

| Manometry index | Volume before BF | Volume after BF | Statistic value |

| Anal canal (mmHg) | |||

| Average rest pressure | 49.7 ± 7.7 | 19.4 ± 10.1 | P < 0.05 |

| Voluntary squeeze | 112.5 ± 18.5 | 164.4 ± 40.6 | NS |

| Rectum | |||

| Initial sense (ml) | 95.4 ± 39.1 | 41.4 ± 19.2 | P < 0.05 |

| Maximum tolerable (ml) | 195.7 ± 42.5 | 412.6 ± 235.3 | NS |

| Compliance (ml/mmHg) | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 6.3 ± 2.9 | NS |

The general symptomatic index was significantly reduced after biofeedback therapy (from 44.80 ± 33.34 before BF to 24.05 ± 20.62 after BF, P < 0.01). All the factors were improved after BF, and except photic anxiety, all the factors had a significant difference between before and BF (P < 0.05-0.01, Table 5, Table 6).

| Factors | Percent of success (31) | Percent of failure (19) | Statistic value |

| Gender | |||

| Female (36) | 22 (72.8%) | 14 (73.7%) | NS |

| Male (14) | 9 (28.1%) | 5 (26.3%) | NS |

| Methods of BF | |||

| EMG-based (30) | 20 (64.5%) | 10 (52.6%) | NS |

| Manometry-based (20) | 11 (36.1%) | 9 (47.3%) | NS |

| Types of constipation | |||

| Slow transit (8) | 3 | 5 | |

| Pelvic floor dysfunction (36) | 26 (83.9%) | 10 (52.6%) | P < 0.05 |

| Mixed (6) | 2 | 4 | |

| Psychological state | |||

| High-level group a(25) | 15 (49.43%) | 10 (52.6%) | NS |

| low-level group a(25) | 16 (51.6%) | 9 (47.3%) | NS |

| Factors | Before BF | After BF |

| Somatization | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| Depression | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Anxiety | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| Hostility | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Padanoid ideation | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Psychoticism | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Photic anxiety | 0.1 | 0.1 |

No practice of biofeedback techniques after treatment was significantly associated with poor outcome immediately after biofeedback treatment (practised: 76% in the success group versus 43% in the failure group, P < 0.01, χ2 test), however, this difference at long-term follow up was no longer significant. Patients with slow transit gained more benefit than those with normal transit, but the number of patients with slow transit was too small to draw conclusion. Patients with normal pelvic floor contraction gained less benefit than those with abnormal one. Different methods of biofeedback did not predict outcome.

This study showed that biofeedback was a successful treatment for patients with constipation unresponsive to other treatments. 62% of patients reported a subjective improvement in long-term follow up. This was objectively supported by their decreased use of laxatives. Symptom improvement was related not only to bowel frequency, but also to symptoms such as bloating.

The biofeedback component was important. Similar training without biofeedback from the sphincter was not effective, as was shown in a recent study by Bleijenberg and Kuijpers[12]. They compared the efficacy of EMG biofeedback with that of retraining defecation using an intrarectal balloon only. In the former group, 8 of 11 patients improved as opposed to only 2 of 9 in the latter group. The efficacy of biofeedback over other treatments was also demonstrated by Loening-Baucke[13], who studied children with constipation and encopresis. Nineteen patients were treated with conventional therapy combined with EMG feedback, 7 months later, 77% of the biofeedback-treated children improved as opposed to only 13% of those treated conventionally.

Our selection of patients for biofeedback was based on international criteria for functional constipation-Roma II criteria. Organic lesions were excluded by colonoscopy or barium enema, as Hirschsprung’s disease and megarectum by anorectal manometry. According to the criteria, the patients were divided into slow transit, pelvic floor dysfunction and mixed. Others had their own opinions on classification. Another type associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) that was defined as combination of normal transit and normal pelvic floor function was reported, Pemberton reported 71.1% of constipated patients (n = 277) had IBS (n = 197). Nyam reported 59.2% (597) of 1009 patients belonged to this type. Glia A and Lindberg G found that 35% of the constipated patients complained of constipation but had no detectable disturbance of anorectal or colonic function, and thought that the methods were too crude to detect clinically relevant disturbances of colorectal function. The patients with normal transit constipation more often reported normal stool frequency, alternating diarrhea and constipation, urgent need for defecation, history of previous anorectal surgery, and looser stools at onset of pain. In the absence of a quantifiable abnormality, patients with normal-transit constipation previously diagnosed as IBS. Our data showed that the International Working Team criteria for IBS did not discriminate between different diagnostic groups. Further studies are needed to determine if a modification of the IBS criteria works well.

This prospective study shows that biofeedback is an effective behavioral treatment for chronic idiopathic constipation with slow transit and normal transit. Five of 14 patients with slow transit were normal by the end of treatment. This study has also shown that the changes in transit occurred in patients with excessive retained markers are distributed around the colon. The effect may relate to whole colon function or innervations and not just the distal large bowel. Treatment also significantly speed up transit in those with normal transit pretreatment, with 18% reduction in the number of markers present on the follow up transit study.

For such a labor intensive treatment it is important to determine which patients are likely to respond to treatment. In our research, the gender of patients, and the type of constipation, physiological factors and the method of biofeedback could not predict response to treatment.

This study demonstrated that patients with idiopathic constipation had significantly greater psychological morbidity than age matched healthy controls. They had higher levels of depression, anxiety, psychoticism and hostility. This finding was partly reproduced in studies[14,15] which suggested that psychological factors influenced gut function via autonomic efferent neural pathways.

In the meantime, after biofeedback therapy, the general symptomatic index was significantly reduced, and except photic anxiety, all the factors fell down. So it is possible that the biofeedback therapy improved the psychological state.

The mechanism of action of biofeedback treatment is complicated. It was as effective in patients with slow transit as it was in those with paradoxical contraction, 82% of those with paradoxical contraction and 50% of those without paradoxical contraction reported subjective improvements after treatment. Previous studies showed that patients with and without animus, with both slow and normal transit benefited equally from biofeedback[16-18].

There are several mechanisms by which behavioral treatment may have altered gut function and blood flow. Cerebral autonomic control of the gut and its microcirculation may have been changed. Alternatively, it is possible that the observed increases in rectal mucosal blood flow are due to improvement in psychological or social functioning brought about by behavioral treatment.

We are indebted to Drs. Shu-Ling Yuan, Ying-Chao Hu, and Zhang-Rong Jiang for assistance in performing the biofeedback treatment.

Edited by Ren SY and Wang XL

| 1. | Corman M. Colon and Rectal Surgery. 4th ed. U.S.A:. Lippincott-Raven Pubilishers. 1998;368-400. |

| 2. | Ferrara A, De Jesus S, Gallagher JT, Williamson PR, Larach SW, Pappas D, Mills J, Sepulveda JA. Time-related decay of the benefits of biofeedback therapy. Tech Coloproctol. 2001;5:131-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McKee RF, McEnroe L, Anderson JH, Finlay IG. Identification of patients likely to benefit from biofeedback for outlet obstruction constipation. Br J Surg. 1999;86:355-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bleijenberg G, Kuijpers HC. Treatment of the spastic pelvic floor syndrome with biofeedback. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:108-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wiesel PH, Dorta G, Cuypers P, Herranz M, Kreis ME, Schnegg JF, Jornod P. Patient satisfaction after biofeedback for constipation and pelvic floor dyssynergia. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001;131:152-156. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Thompson WG. Constipation: a physiological approach. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14 Suppl D:155D-162D. [PubMed] |

| 7. | De Paepe H, Renson C, Van Laecke E, Raes A, Vande Walle J, Hoebeke P. Pelvic-floor therapy and toilet training in young children with dysfunctional voiding and obstipation. BJU Int. 2000;85:889-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brown SR, Donati D, Seow-Choen F, Ho YH. Biofeedback avoids surgery in patients with slow-transit constipation: report of four cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:737-79; discussion 737-79;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nehra V, Bruce BK, Rath-Harvey DM, Pemberton JH, Camilleri M. Psychological disorders in patients with evacuation disorders and constipation in a tertiary practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1755-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu SX, Zhang DW, Wu F, Xie RB, Zhang PD, Ma DW, Meng YC, Xiao KS, Tang HQ. The value of whole gut transit time to the diagnosis of constipation. Zhongguo Yixue Zazhi. 1993;73:75-77. |

| 11. | Huang XD, Wang XL, Ma H. Rating Scales For Mental Health. 1st ed. Beijing: Zhongguo Xiliweisheng Zazhishi Publishers. 1999;31-35. |

| 12. | Wiesel PH, Norton C, Roy AJ, Storrie JB, Bowers J, Kamm MA. Gut focused behavioural treatment (biofeedback) for constipation and faecal incontinence in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:240-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McGrath ML, Mellon MW, Murphy L. Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: constipation and encopresis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:225-254; discussion 255-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Devroede G, Girard G, Bouchoucha M, Roy T, Black R, Camerlain M, Pinard G, Schang JC, Arhan P. Idiopathic constipation by colonic dysfunction. Relationship with personality and anxiety. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1428-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dailianas A, Skandalis N, Rimikis MN, Koutsomanis D, Kardasi M, Archimandritis A. Pelvic floor study in patients with obstructive defecation: influence of biofeedback. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:176-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Emmanuel AV, Kamm MA. Response to a behavioural treatment, biofeedback, in constipated patients is associated with improved gut transit and autonomic innervation. Gut. 2001;49:214-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Coulter ID, Favreau JT, Hardy ML, Morton SC, Roth EA, Shekelle P. Biofeedback interventions for gastrointestinal conditions: a systematic review. Altern Ther Health Med. 2002;8:76-83. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Heymen S, Wexner SD, Vickers D, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Pikarsky AJ. Prospective, randomized trial comparing four biofeedback techniques for patients with constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1388-1393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |