Published online May 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i5.984

Revised: April 23, 2002

Accepted: December 22, 2002

Published online: May 15, 2003

AIM: Clinical therapy and prognosis in HCV infections are not good, and mix-infections with different HCV genotypes or quasispecies and mix-infections with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses are important concerns worldwide. The present report describes the sequence diversity and genotying of the 5’NCR of HCV isolates from hepatitis patients mix-infected with different HCV genotypes or variants, and the conditions of mix-infections with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses, providing important diagnostic and prognostic information for more effective treatment of HCV infections.

METHODS: The 5’ non-coding region (5’NCR) of HCV was isolated from the patients sera and sequenced, and sequence variability and genotypes of HCV were defined by nucleotide sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis, and the patients mix-infected with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses were analyzed. The conditions and clinical significance of mix-infections with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses were further studied.

RESULTS: Twenty-four out of 43 patients with chronic hepatitis C were defined as mix-infected with different genotypes of HCV. Among these 24 patients, 9 were mix-infected with genotype 1 and 3, 7 with different variants of genotype 1, 2 with different variants of genotype 2, 6 with different variants of genotype 3. No patients were found mix-infected with genotype 1 and 2 or with genotype 2 and 3. The clinical virological analysis of 60 patients mix-infected with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses showed that 45.0% of the patients were mix-infected with HCV plus HAV, 61.7% with HCV plus HBV, 6.7% with HCV plus HDV/HBV, 8.4% with HCV plus HEV, 3.3% with HCV plus HGV. Infections with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses may exacerbate the pathological lesion of the liver.

CONCLUSION: The findings in the present study imply that mix-infections with different HCV genotypes and mix-infections with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses were relatively high in Yunnan, China, providing important diagnostic and prognostic information for more effective treatment of HCV infections.

- Citation: Chen YD, Liu MY, Yu WL, Li JQ, Dai Q, Zhou ZQ, Tisminetzky SG. Mix-infections with different genotypes of HCV and with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses in patients with hepatitis C in China. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(5): 984-992

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i5/984.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i5.984

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the major causative agent of non-A, non-B pasttransfusional hepatitis, possessing a positive-stranded RNA genome of 9.4 kb[1]. Since the discovery of HCV, investigations showed that HCV genome has great diversity, proposing that HCV isolates be classified into different groups (genotypes) or subtypes. HCV sequence diversity observed among isolates relevant to the process of viral evolution as it occurred during the history of human populations[2]; therefore, it has been largely exploited to classify viral variants showing different epidemiological and pathogenic features[3]. Conversely genetic diversity within individuals is more pertinent to the long-term adaptation of the virus to the host and reflect the dynamics of viral population and the selective mechanisms operating during the course of the infection[4], formation of persistent and chronic infections[5,6].

Clinic therapy and prognosis in HCV infections are not good. More than 50% of individuals exposed to HCV develop chronic infection, and of those individuals chronically infected, approximately 20% to 30% will develop liver cirrhosis and/or hepatocelullar carcinoma when followed a twenty to thirty years[5,7]. For those results, in addition to HCV infection, mix-infection (co-infection or super-infection) with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses might have important significance in these situations. It was previously believed that some of the individuals with hepatitis C might in fact be mix-infected by HCV plus other hepatitis viruses. In such cases, HCV viremia clearance might be observed after clinical treatment directed to HCV infection, but the serum ALT level be not normalized or only transiently decreased. Mix-infection with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses is an important concern worthy further investigation.

The present report described the sequence diversity and genotying of the 5’NCR of HCV isolates from hepatitis patients mix-infected with different HCV genotypes or variants, and the conditions of mix-infections with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses in Yunnan, China.

The cases described in this study are all Chinese patients in Yunnan province clinically diagnosed with liver diseases mix-infected with different HCV genotypes or variants, or with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses. The serum specimens were collected from the patients for virological tests.

HCV-RNA extraction HCV-RNA was extracted from the sera of patients with hepatitis C by the guanidinium lysis and phenol-chloroform method described previously[8]. The HCV RNA extract from 450 μl of serum was finally dissolved in 45 μl of distilled water.

HCV PCR HCV-positive serum specimens were obtained from patients with hepatitis infected by HCV, and the details of RT-PCR method used to generate the double-stranded cDNA fragment have been described elsewhere[8], with some modification. Briefly, 45 μl of RNA was extracted from 450 μl of serum as described previously, and the antisense primer AS-1 (5’-GTGCACGGTCTACGAGACCT-3’) derived from the 5’NCR was used in a reverse transcriptase reaction to generate a cDNA copy of the antisense strand. Synthesis of HCV cDNA was performed from 2 μl of RNA extract, mixed with 13 μl of pre-RT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM spermidine, 10 mM DTT, 1.25 mM of the four dNTPs [Promega Biological Products Ltd., Shanghai, China] and 150 ng of the AS-1). After heat treated for 30 s at 92 °C and quick chilling, the above mix was added with 5 μl of RT buffer containing 20 u of RNasin and 10 u AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Shanghai, China) and then incubated for 1 hr at 42 °C.

Twenty microliters of cDNA from each reverse transcriptase reaction was used as a template for the first subsequent PCR in a DNA Thermal Cycler (Perkin-Elmer/Cetus, CA., USA). The first PCR was performed in a reaction volume of 100 μl containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH9.0), 50 mM KCl, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton x-100, 5 mM of each dNTPs, 5 u Taq DNA polymerase [Promega], 150 ng of primers AS-1 and S-1 (5’-GCCATGGCGTTAGTATGAGT-3’) and 20 μl of cDNA. The PCR was performed for 30 cycles at 94 °C for 45 s, 56 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 45 s.

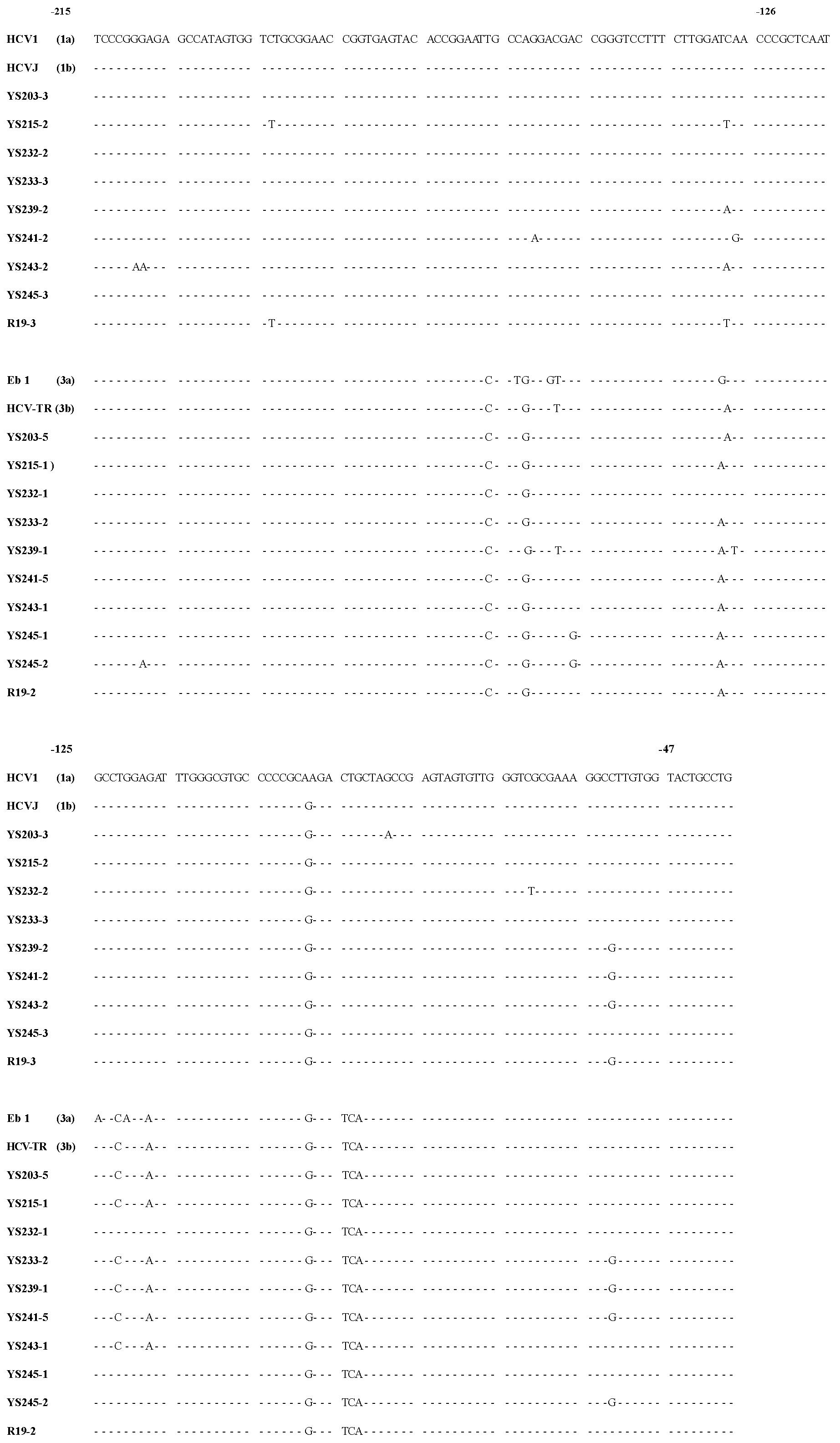

Cloning and sequencing One μl aliquot of the first PCR product (comprising nucleotides-240 to -22) was used as a template for the second of PCR amplification, using a new pair of primers AS-2 (5’-CGGGGAGCTCGCAAGCACCCTAT-3’), S-2 (5’-GTCGTGGTACCTCCAGGACC-3’). The conditions of the second PCR reaction were the same as described above, except the primers AS-2 and S-2 which induced restriction endonuclease sites (underlined) Kpn I (GGTACC) and Sac I (GAGCTC) on the 5’- and 3’-end of the PCR product. The second PCR product (comprising nucleotides -220 to -47) was then cut with enzymes Kpn I/Sac I and inserted into pBluescript II K/S +/- (pBS) cloning vector by standard procedures. Clones were sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method with phage T7 DNA polymerase (T7SequencingTM, Pharmacia Biotech Inc. USA) (Figure 1). To minimize sequencing errors due to sequencing reaction and electrophoresis artifacts, all the clones were sequenced in both directions.

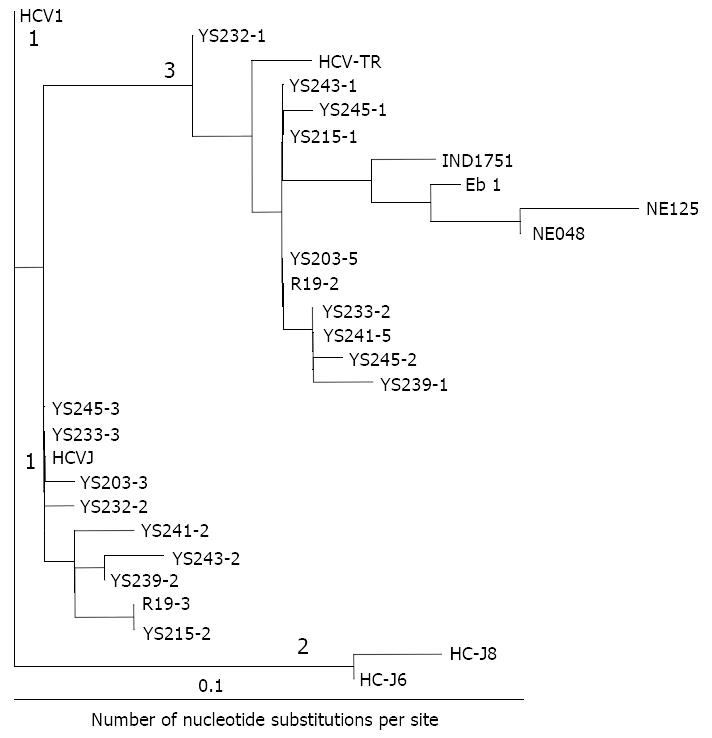

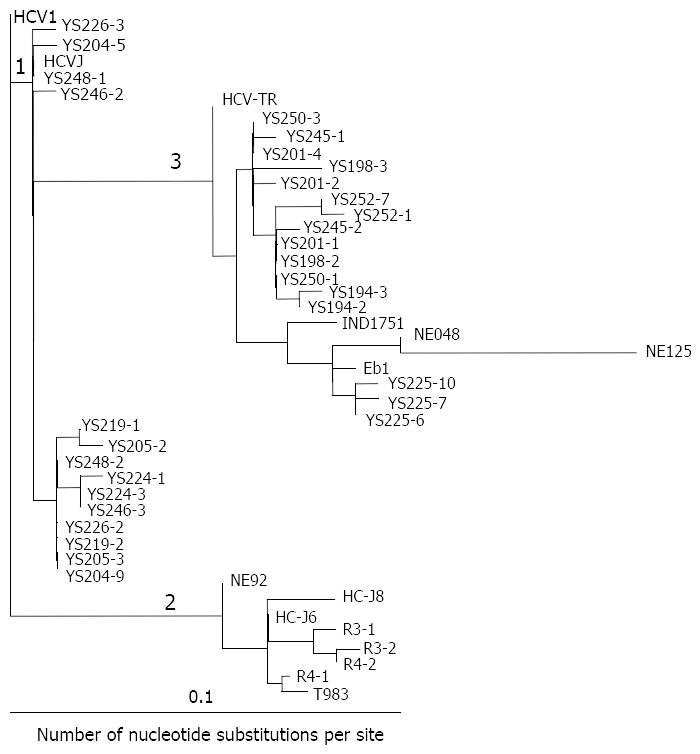

Sequence analysis To make a comparative analysis with reported sequences, sequences of the 5’NCR were compared with the consensus sequence of HCV-1[9]. Genalign was used for sequence alignments and comparison (Intelligenetics). A phylogenetic tree for HCV was constructed by the previously described method[10]. Briefly, evolutionary distance (i.e. those corrected for multiple substitution) between pairs of sequences were estimated using the DNADIST program in the PHYLIP package[11]. Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the programs DNADIST, NEIGHBOR and DRAWTREE in the PHYLIP package[11].

Anti-HAV detection Serum anti-HAV IgM was examined with an ELISA kit (Beijing Science & Health Clinic Diagnostics Company, Beijing) as described in the manual.

HBV detection HBV infection markers including HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc, HBeAg were examined with ELISA kits (Beijing Biochemical & Immunological Reagent Company, Beijing). HBV-DNA was examined by PCR. The patients positive for at least two of the above markers were considered HBV-infected cases.

HCV detection Serum anti-HCV was examined with a second generation ELISA kit (AxSYM, Abbott Laboratories Diagnostics Division, USA) and the 5’NCR of HCV genome was examined by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) as described previously[8]. The patients positive for both anti-HCV and HCV-RNA were considered HCV-infected cases.

Anti-HDV detection Serum anti-HDV was examined with an ELISA kit (Beijing Science & Health Clinic Diagnostics Company, Beijing).

Anti-HEV detection Anti-HEV IgM was examined with an ELISA kit (Genelab Diagnostics PTE LTD, Singapore).

Anti-HGV detection HGV-RNA was examined by RT-PCR with HGV specific primers[12].

Serum ALT detection Serum ALT was examined by Rate’s method.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann Witney test and Fisher’s exact test[13].

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this study have been deposited in the Genbank and EMBL Databases under the following accession numbers: AJ388314 to AJ388391. Genbank accession numbers of the previously reported sequences cited in this study are HCV1 (1a), M62321; HCVJ (1b), D90208; HC-J6 (2a), D00944; HC-J8(2b), D10988; NE92 (2d), X78862; Eb1 (3a), D10114; HCV-TR (3b), D11433; NE048 (3c), D16612; NE125 (3f), D16614; IND1751 (3g), X91421; T983 (2c), Ref. 14.

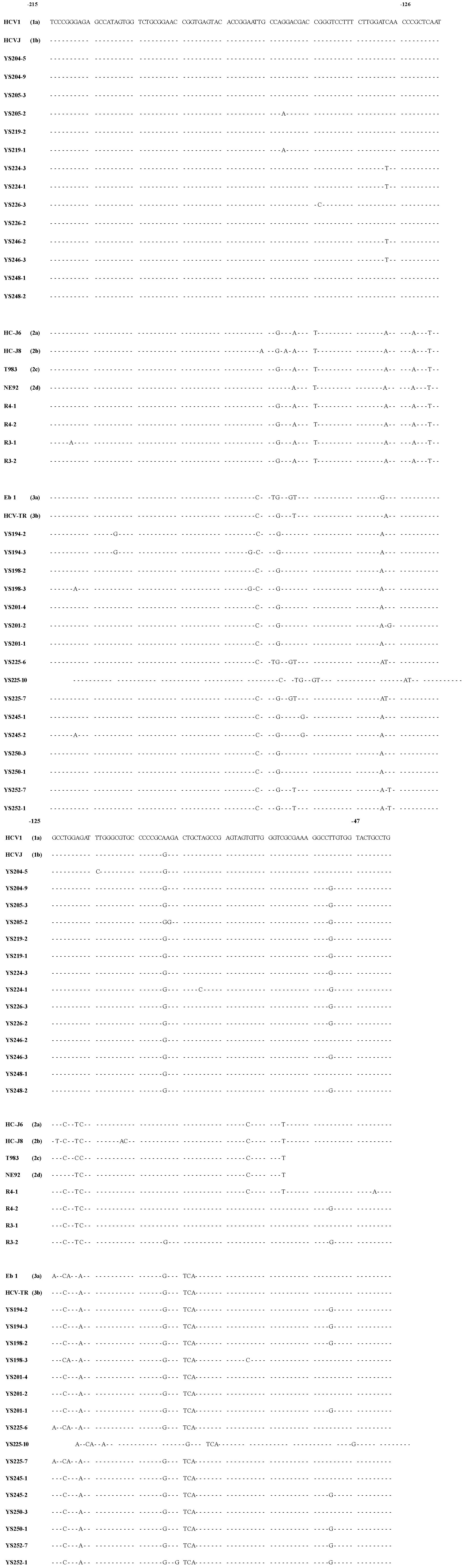

Forty-three serum samples from HCV antibody-positive patients with chronic hepatitis were analyzed by RT-PCR. The alignment of the DNA sequences (Figure 1 and Figure 2) showed that 24 patients were mix-infected with different HCV genotypes or variants. Among these 24 patients, 9 were mix-infected with genotype 1 and 3 (Figure 1), 7 with different variants of genotype 1, 2 with variants of genotype 2, and 6 with variants of genotype 3 (Figure 2). There were no patients mix-infected with genotype 1 and 2 or mix-infected with genotype 2 and 3. Phylogenetic analysis with DNADIST (Figure 3 and Figure 4) clearly demonstrated these results.

Nineteen isolates were cloned from the nine patients mix-infected with genotype 1 and 3 (Figure 1). Of them only 2 isolates (YS233-3 and YS245-3) were found possessing the sequence completely identical to the previously reported genotype 1b (HCVJ)[15]. Two isolates (YS203-3 and YS232-2) possessed high sequence homology with genotype 1b. The remaining sequences were quite different from the existing (classified) genotypes reported previously.

Fourteen isolates were cloned from the seven individuals mix-infected with different variants of genotype 1, and only 2 isolates (YS246-2 and YS248-1) were found possessing the sequences completely identical to HCVJ (1b). Four isolates were cloned from the two patients mix-infected with different variants of genotype 2, and only one (R4-1) was found possessing sequence quite similar to T983 (genotype 2c)[14].

Fifty one isolates were obtained from the 24 mix-infected patients, and only 5 isolates were found possessing the sequences completely identical to the known HCVJ (genotype 1b), the remaining possess high variability from the known genotypes. On the other side, isolates cloned from different individuals might possess the completely identical sequences, such as YS233-3 and YS245-3 (Figure 1); YS203-5, YS215-1, YS243-1, R19-2 (Figure 1), YS201-4 and YS250-3 (Figure 2); YS233-2 (Figure 1) and YS250-1 (Figure 2); YS239-1 (Figure 1) and YS252-7 (Figure 2).

The sequence analyzing found that out of 51 isolates, 29 (57%) possessed a G at nucleotide position -61, in place of the "T" that was present in all previously reported sequences. Of them, 14 were in genotype 1, 2 in genotype 2, 13 in genotype 3.

In order to detect the conditions of mix-infection with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses, HAV, HBV, HDV, HEV and/or HGV infection markers were detected in 82 patients HCV chronically infected. The results showed that 60 patients were mix-infected with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses. The incidence was very high. Among these cases, 30.0% (18/60) were mix-infected with HCV plus HAV, 46.7% (28/60) with HCV plus HBV, 18.3% (11/60) with HCV plus other two or three hepatitis viruses (Table 1). The individuals mix-infected with HCV plus HDV were all infected with HBV. Among these HCV infected patients, the positive rates of HAV, HBV, HDV, HEV and HGV were 45.0%, 61.2%, 6.7%, 8.3% and 3.3%, respectively (Table 2).

| Case | Positive cases (%) | ||||||||||

| HCV+ HAV+ | HCV+ HBV+ | HCV+ HEV+ | HCV+ HGV+ | HCV+ HAV+ HBV+ | HCV+ HAV+ HEV+ | HCV+ HAV+ HGV+ | HCV+ HBV+ HDV+ | HCV+ HBV+ HEV+ | HCV+ HAV+ HBV+ HDV+ | HCV+ HAV+ HBV+ HEV+ | |

| 60 (%) | 18 (30.0) | 28 (46.7) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.7) | 3 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 3 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) |

| Case | Positive cases (%) | ||||

| HAV | HBV | HDV | HEV | HGV | |

| 60 | 27 (45.0%) | 37 (61.2%) | 4 (6.7%) | 5 (8.3%) | 2 (3.3%) |

The ages and serum ALT levels in different group patients were showed in Table 3.

| Group | Subtotal | Male | Female | |||

| Age (years) | ALT (U/L) | Age (years) | ALT (U/L) | Age (years) | ALT (U/L) | |

| HCV+ | 35.9 (20-57) | 577.7 (20-1890) | 33.5 (20-57) | 580.8 (20-1890) | 38.9 (20-48) | 572.9 (121-1000) |

| [718/20] | [11553/20] | [368/11] | [6970/12] | [350/9] | [4583/8] | |

| HCV+ + HAV+ | 18.9 (4-40) | 1253.4 (92-2350) | 18.8 (6-40) | 1108.5 (92-2080) | 19 (4-37) | 1398.4 (208-2350) |

| [302/16] | [20055/16] | [150/8] | [8868/8] | [152/8] | [11187/8] | |

| HCV+ + HBV+ | 34.6 (18-71) | 741 (30-2745) | 35.7 (18-53) | 610.4 (30-1905) | 32.4 (19-71) | 1016.7 (35-2745) |

| [970/28] | [20748/28] | [678/19] | [11598/19] | [292/9] | [9150/9] | |

| HCV+ + other | 29.3 (14-64) | 1266.5 (49-4160) | 27.6 (14-54) | 1090.4 (49-3800) | 32.6 (16-64) | 1618.8 (345-4160) |

| hepatitis viruses | [439/15] | [18998/15] | [276/10] | [10904/10] | [163/5] | [8094/5] |

| Total | 30.7 (4-71) | 803.2 (20-4160) | 30.7 (6-57) | 799.5 (21-3800) | 30.9 (4-71) | 1100.5 (35-4160) |

| [2429/79] | [71354/79] | [1472/48] | [38375/48] | [95/31] | [33014/30] | |

The mean age of individuals infected singly with HCV was 35.9 years old, older than those mix-infected with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses. The mean age of the patients mix-infected with HCV plus HAV was 18.9 years old, which was significantly younger than that (35.9 years) singly infected with HCV (P < 0.001), mix-infected with HCV plus HBV (34.6%) (P < 0.001) or mix-infected with HCV plus other one or more viruses (29.3 years) (P < 0.001). The serum ALT level of the patients mix-infected with HCV plus HAV was 1253.4 U/L, which was significantly higher than that (577.7 U/L) singly infected with HCV (P < 0.001) or than that (741 U/L) mix-infected with HCV plus HBV (P < 0.05) (Table 3). The mean age of the patients mix-infected with HCV plus HAV was significantly younger than that mix-infected with HCV plus HBV (P < 0.001), no matter whether they were mix-infected with other hepatitis viruses or not (Table 3 and Table 4).

| Group | Subtotal | Male | Female | |||

| Age (years) | ALT (U/L) | Age (years) | Age (years) | ALT (U/L) | Age (years) | |

| HCV+ +HAV+ | 26.9 (14-64) | 1521.9 (233-4160) | 21.6 (14-41) | 1552.6 (233-3800) | 33.5 (16-64) | 1483.5 (345-4160) |

| [242/9] | [13697/9] | [108/5] | [7763/5] | [134/4] | [5934/4] | |

| HCV+ +HBV+ | 34.3 (26-64) | 771.8 (49-2680) | 31.8 (26-50) | 772 (49-2680) | 39.3 (54-64) | 591.3 (234-1429) |

| [309/9] | [6406/9] | [191/6] | [4632/6] | [118/3] | [1774/3] | |

There were no significant differences in mean ages or in mean ALT levels between two sex individuals within different groups.

High variability of HCV genome appears not only in its highly variable region (HVR) of E2 protein, but also in the most highly conserved 5’NCR. The 5’NCR is the first generation of direct sequencing tests which provide complete sequence information to characterize HCV genotypes[8,14]. However, the previously reported sequence comparisons between isolates were mainly cloned from the same individuals and focused on HVR of E2 or C protein region[6,16-18], and largely within the same genotype. Isolates of HCV genome cloned from the same individual could belong to the same genotype[16] or the different genotype[19]. The previous report showed that HVR1 of HCV variation had an adaptive significance and was associated with favorable features of liver disease[6] and the 5’NCR did so as showed in the present study. The findings in the present study showed that mix-infections within the same individual with different HCV genotypes or variants commonly existed, and mix-infection with genotype 1 plus genotype 3 were only found in the present study up to now in China. No genotype 1/2 or genotype 2/3 mix-infected cases were found in the present study. Different HCV genotypes or variants existed within the same individual. Most of the viral sequences found in the present study had high diversity from previously reported, implying that HCV genotypes in China had specific geographic distributions and epidemiological features.

Considerable sequence diversity exists both among isolates from unrelated individuals and within the same individual, implying that the virus is not a single molecular species, but as a variable population of closely related or unrelated genomes, according to the model of the viral genotypes or quasispecies. The pathogenetic mechanisms responsible for persistent HCV infection and progressive liver disease are largely unclear; nonetheless, variant genotypes or quasispecies presence was thought favorable to escaping from immune surveillance, leading to chronicity. In fact, the immune response failed to eradicate HCV infection and did not confer protection[20], despite the continuous presence of antibodies[21-23] and cytotoxic T-cell[24,25]. This phenomenon is likely to result in the continuous selection of new variants.

The previous reports showed that different HCV genotypes had different clinical pathological features and had different response to interferon therapy, while very few reports described clinical pathologic implications of mix-infection with different genotypes or variants. This is worthy to further study.

A considerable number of HCV/HAV or HCV/HBV mix-infections were observed in this study. Among the studied cases, only 26.8% (22/82) of the patients were singly infected with HCV. The results showed that the mean age was lower and the mean ALT level was higher in the patients mix-infected with HCV plus other hepatitis virus than in the patients singly infected with HCV. These findings implied mix-infection with HCV plus other hepatitis virus might exacerbate pathological lesion of the liver, accelerating the progress of liver disease. Affections by HAV super-infection were most significant.

HCV infection has become an important public health problem worldwide including China[26], and mix-infections among the patients with liver diseases with HCV plus other hepatitis viruses in China seems to be also a common problem. There were a lot of investigations about infections with only single HCV or other hepatitis viruses, but only few involved in mix-infections with HCV plus HAV[27], HCV plus HBV[28-31], HCV plus HDV[28,32], or HCV plus HGV[12,28,33-35], with high incidence rate has been reported in China. While there were no investigations involved the cases mix-infected with HCV plus so many hepatitis viruses with clinical features in China and even abroad. The findings in the present study showed that patients might get mix-infections with HCV plus one, two or three other hepatitis viruses. The positive rate in the patients mix-infected with HCV plus HBV was very high, implying that mix-infection with HCV plus HBV have great significance in diagnosis and treatment of HCV infected patients. Besides, mix-infection with HCV plus HIV would not be another ignorable public health problem in China today, especially in blood donors and drug abusers[26,36,37]. The preliminary results obtained in the present study would provide important diagnostic and prognostic information for more effective treatment of HCV infections. In order to get better insight in the whole conditions of mix-infection of different hepatitis viruses more investigations are still necessary.

We are indebted to Professor Francisco E. Baralle (International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, ICGEB) for his technical assistance in the present study, careful reading of the manuscript and for helpful discussions. This study was supported by research grants from ICGEB Collaborative Research Program (CRP/CHN96-05) and from China Yunnan Provincial Science & Technology Commission International Collaborative Research Program (97C009).

Edited by Zhang JZ

| 1. | Farci P. Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome [Science 1989; 244: 359-362]. J Hepatol. 2002;36:582-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4996] [Cited by in RCA: 4657] [Article Influence: 129.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bukh J, Miller RH, Purcell RH. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus: quasispecies and genotypes. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:41-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 574] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Mondelli MU, Silini E. Clinical significance of hepatitis C virus genotypes. J Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 1:65-70. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Holland JJ, De La Torre JC, Steinhauer DA. RNA virus populations as quasispecies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;176:1-20. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Heintges T, Wands JR. Hepatitis C virus: epidemiology and transmission. Hepatology. 1997;26:521-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brambilla S, Bellati G, Asti M, Lisa A, Candusso ME, D'Amico M, Grassi G, Giacca M, Franchini A, Bruno S. Dynamics of hypervariable region 1 variation in hepatitis C virus infection and correlation with clinical and virological features of liver disease. Hepatology. 1998;27:1678-1686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cuthbert JA. Hepatitis C: progress and problems. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:505-532. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Chen YD, Liu MY, Yu WL, Li JQ, Peng M, Dai Q, Wu J, Liu X, Zhou ZQ. Sequence variability of the 5' UTR in isolates of hepatitis C virus in China. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:541-552. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Choo QL, Richman KH, Han JH, Berger K, Lee C, Dong C, Gallegos C, Coit D, Medina-Selby R, Barr PJ. Genetic organization and diversity of the hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2451-2455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1133] [Cited by in RCA: 1132] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Simmonds P, Mellor J, Sakuldamrongpanich T, Nuchaprayoon C, Tanprasert S, Holmes EC, Smith DB. Evolutionary analysis of variants of hepatitis C virus found in South-East Asia: comparison with classifications based upon sequence similarity. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:3013-3024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3. 5c. Distributed by the author. Department of Genetics, Univer-sity of Washington. Seattle, USA. 1993;. |

| 12. | McHutchison JG, Nainan OV, Alter MJ, Sedghi-Vaziri A, Detmer J, Collins M, Kolberg J. Hepatitis C and G co-infection: response to interferon therapy and quantitative changes in serum HGV-RNA. Hepatology. 1997;26:1322-1327. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Tisminetzky SG, Gerotto M, Pontisso P, Chemello L, Ruvoletto MG, Baralle F, Alberti A. Genotypes of hepatitis C virus in Italian patients with chronic hepatitis C. Int Hepatol Commun. 1994;2:105-112. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Halfon P, Trimoulet P, Bourliere M, Khiri H, de Lédinghen V, Couzigou P, Feryn JM, Alcaraz P, Renou C, Fleury HJ. Hepatitis C virus genotyping based on 5' noncoding sequence analysis (Trugene). J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1771-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bhattacherjee V, Prescott LE, Pike I, Rodgers B, Bell H, El-Zayadi AR, Kew MC, Conradie J, Lin CK, Marsden H. Use of NS-4 peptides to identify type-specific antibody to hepatitis C virus genotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1737-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pan W, Wang H, Wang T. [Comparison of hypervariable region gene of hepatitis C virus between an individual infected persistently and an individual recovered from infection]. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 1999;7:26-28. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Fang F, Pan W, Qi ZT, Song YB, Zhu SY. Sequence characteriza-tion of hypervariable region 1 of the putative envelope protein 2 in Chinese HCV isolates. Zhongguo Bingduxue. 1998;13:35-39. |

| 18. | Zhang W, Yu H, Wang X, Wang Q, Lu R, Wang HQ, Shao JJ. [Analysis of the nucleotide sequence for C and NS5 regions and the genotype of HCV isolate in Shandong Province]. Zhonghua Shiyan He Linchuang Bingduxue Zazhi. 2001;15:219-221. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Song HS, Wang HT, Tang SX, Ji BX, Wang TX, Zhang XT. HCV genotypes and distributions in patients coinfected by different HCV genotypes. Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 1999;20:227. |

| 20. | Farci P, Alter HJ, Govindarajan S, Wong DC, Engle R, Lesniewski RR, Mushahwar IK, Desai SM, Miller RH, Ogata N. Lack of protective immunity against reinfection with hepatitis C virus. Science. 1992;258:135-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Weiner AJ, Geysen HM, Christopherson C, Hall JE, Mason TJ, Saracco G, Bonino F, Crawford K, Marion CD, Crawford KA. Evidence for immune selection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) putative envelope glycoprotein variants: potential role in chronic HCV infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3468-3472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Taniguchi S, Okamoto H, Sakamoto M, Kojima M, Tsuda F, Tanaka T, Munekata E, Muchmore EE, Peterson DA, Mishiro S. A structurally flexible and antigenically variable N-terminal domain of the hepatitis C virus E2/NS1 protein: implication for an escape from antibody. Virology. 1993;195:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kato N, Sekiya H, Ootsuyama Y, Nakazawa T, Hijikata M, Ohkoshi S, Shimotohno K. Humoral immune response to hypervariable region 1 of the putative envelope glycoprotein (gp70) of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 1993;67:3923-3930. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Koziel MJ, Dudley D, Afdhal N, Grakoui A, Rice CM, Choo QL, Houghton M, Walker BD. HLA class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for hepatitis C virus. Identification of multiple epitopes and characterization of patterns of cytokine release. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2311-2321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rehermann B, Chang KM, McHutchinson J, Kokka R, Houghton M, Rice CM, Chisari FV. Differential cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responsiveness to the hepatitis B and C viruses in chronically infected patients. J Virol. 1996;70:7092-7102. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Chen YD, Liu MY, Yu WL, Li JQ, Peng M, Dai Q, Liu X, Zhou ZQ. Hepatitis C virus infections and genotypes in China. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:194-201. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Tang BY, Huang ZH, Li J, Min X. Investigation of anti-HCV in sera from patients with viral hepatitis in part areas in Jiangsu Province. Nanjing Yikedaxue Xuebao. 1993;13:252-255. |

| 28. | Fan XL, Peng WW, Yao JL, Zhou YP, Lu L, Zheng XC, Chen Q. Infection of HBV, HCV and HDV in hepatocelullar carcinoma. Zhonghua Chuanranbing Zazhi. 1995;13:129-132. |

| 29. | Du S, Tao Q, Chang J. [Studies on multiple infection with hepatitis B, C and G viruses]. Zhonghua Yufangyixue Zazhi. 1998;32:13-15. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Wang J, Zhao H, Zhao S. [Prevalence of HCV and HBV infection in patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma in Shanxi Province]. Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 1999;20:215-217. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Shimbo S, Zhang ZW, Gao WP, Hu ZH, Qu JB, Watanabe T, Nakatsuka H, Matsuda-Inokuchi N, Higashikawa K, Ikeda M. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection markers among adult women in urban and rural areas in Shaanxi Province, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:263-268. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Wei JR, Liu JL, Zhang YK, Zhang QS. Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C virus infection and hepatocelullar carcinoma. Zhonghua Chuanranbing Zazhi. 1997;15:151-153. |

| 33. | Wang H, Sun Y, Chang J. [The coinfection of hepatitis C virus with hepatitis G virus and its reaction to interferon treatment]. Zhonghua Shiyan He Linchuang Bingduxue Zazhi. 1998;12:377-379. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Wang Y, Chen HS, Fan MH, Liu HL, An P, Sawada N, Tanaka T, Tsuda F, Okamoto H. Infection with GB virus C and hepatitis C virus in hemodialysis patients and blood donors in Beijing. J Med Virol. 1997;52:26-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wu RR, Mizokami M, Cao K, Nakano T, Ge XM, Wang SS, Orito E, Ohba K, Mukaide M, Hikiji K. GB virus C/hepatitis G virus infection in southern China. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:168-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhu B, Wu N, Qiang L, Shao Y. [The serologic study on the blood transmission origin of HIV]. Zhonghua Liuxingb ingxue Zazhi. 2000;21:140-142. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Zhang C, Yang R, Xia X, Qin S, Dai J, Zhang Z, Peng Z, Wei T, Liu H, Pu D. High prevalence of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection among injection drug users in the southeastern region of Yunnan, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:191-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |