INTRODUCTION

Hemobilia, a phenomenon of bleeding into the biliary tree, is an unusual cause of obscure upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Most of the etiologies of hemobilia are iatrogenic or traumatic in origin[1]. An hepatic artery aneurysm is a rare vascular lesion that accounts for nearly 10% of hemobilia cases[2], and is mostly due to atherosclerosis or trauma[3,4]. A hepatic artery aneurysm due to biliary inflammation is less frequent and usually attributed to parasites or stone obstruction in the biliary tract[5]. Inflammatory causes of hemobilia in the Far East are mainly due to parasitic infections, such as ascariasis or clonorchiasis, which have the tendency to invade the bile ducts and induce bleeding. Impacted stones may also erode the biliary mucosa and lead to bleeding. Severe hemobilia is rare, but can occur when a large stone erodes vessels of the hepatoduodenal ligament or the cystic artery[6]. In contrast, hemobilia caused by reflux cholangitis without stones or parasitic infection, has not yet been reported and its mechanism is unclear. We present a case of life-threatening hemobilia from an hepatic pseudoaneurysm, complicated by reflux cholangitis due to previous biliary surgery.

CASE REPORT

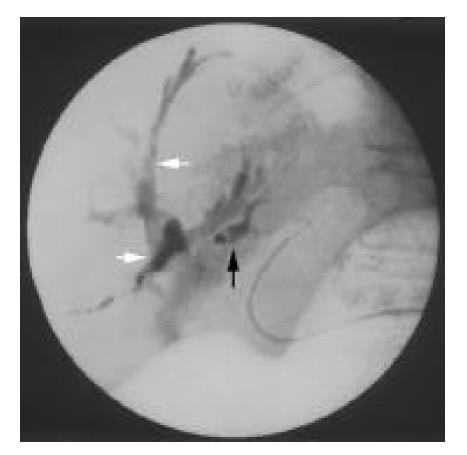

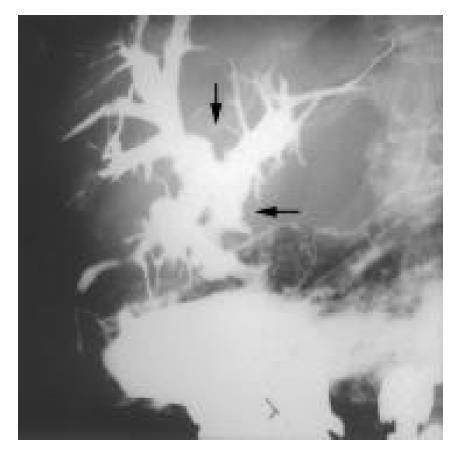

A 74-year-old woman had a history of biliary stones and received a cholecystectomy, hepatic lateral segmentectomy and sphincterotomy over 30 years ago. In March 2001, she developed intermittent tarry stools and dizziness for one week and came to our hospital. At the emergency room, her blood pressure was 99/35 mmHg and her pulse rate was 93/minute. Physical examination showed a pale conjunctiva and mild epigastric tenderness. A hemogram showed microcytic hypochromic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 7.6 g/dl. An emergent gastro-duodenal endoscopy disclosed gastric ulcers near the angularis. Proton pump inhibitor therapy was started. On the third hospital day, massive hematemesis with hypovolemic shock occurred. An emergent endoscopy did not disclose any evidence of recent bleeding from the gastric ulcers, but a lot of fresh blood in the duodenal bulb and beyond was observed. An immediate angiography, Tc-99m-RBC scan, and colonoscopy all returned negative findings. An abdominal CT did not display any abnormal lesions. A small intestines series did not disclose any abnormal lesions, except an obvious contrast medium reflux from the duodenum into biliary tree (Figure 1). In the following days, intermittent tarry stools continued to pass. She suffered from upper abdominal pain before every bleeding episode. On the 16th day of admission, she had another massive hematochezia with hypovolemic shock. This time, the emergent endoscopy showed fresh blood flowing from the orifice of the ampulla of Vater. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography found widening of the papillary orifice and amorphous filling defects of blood clots retained in the irregular and dilated biliary trees. An angiography showed a small pseudoaneurysm over the middle hepatic artery. Injection of a contrast medium into the middle hepatic artery also opacified the intrahepatic biliary ducts (Figure 2). A coil embolization was performed smoothly and no more event of hemobilia has been reported after this procedure.

Figure 1 Small intestines series show chronic cholangitis with obvious contrast medium reflux into the biliary tree (arrow).

Figure 2 Angiography shows a small pseudoaneurysm (arrow) over the middle hepatic artery.

Injecting the contrast medium into the middle hepatic artery opacified the intrahepatic bil-iary duct (arrowheads).

DISCUSSION

There were many etiologies for hemobilia such as iatrogenic and accidental trauma, gallstones, inflammation, vascular malformations and tumours[1]. Because interventional procedures and laparoscopic cholecystectomy were used more to manage hepatobiliary disorders, iatrogenic origins were the more frequent etiology for hemobilia[1].

Hemobilia due to a hepatic artery aneurysm only accounted for 10% of cases[2], and was mostly due to atherosclerosis or trauma[3,4]. Hepatic artery aneurysms due to biliary inflammation were usually attributed to parasites or stone obstruction in the biliary tract[5], and rarely due to non-obstructive inflammations, as in this case. After sphincterotomy, biliary reflux of the duodenal chyme was observed in most patients, aerobilia in half and bactibilia in all[7,8]. Infected bile may lead to cholangitis in more than 1% of them[9]. Although such a reflux might not always produce clinical symptoms, the biochemical changes suggested that there might be some degree of continuing low-grade damage within the liver parenchyma. Twenty percent of asymptomatic patients undergoing an endoscopic sphincterotomy for biliary stones still had persistent subclinical injury to the biliary tract[10]. Liver biopsy showed periportal fibrosis and inflammation[10]. The bile ducts were richly supplied by the hepatic artery, which forms a peri-biliary vascular plexus[11]. As the inflammation proceeds and involves the collateral hepatic artery, a pseudoaneurysm forms and raises the risk of hemobilia.

The most common symptoms of hemobilia are upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, upper abdominal pain, and jaundice. These occurred in 73%, 52%, and 30% of cases, respectively, although the complete triad occurred in only 22% of the them[1]. For patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, an endoscopy is the first step. If blood or clotting is seen at the ampulla of Vater, hemobilia is the likely cause of the haemorrhage. However, only 12% of these endoscopies might be diagnostic[12]. The choice of subsequent investigations depends on the history and the level of suspicion. Abdominal sonography or computed tomography can detect common bile duct obstruction and identify intrahepatic lesions, such as stones or tumors. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography may be helpful. Blood may be seen at the ampulla of Vater and contrast studies may show filling defects in the biliary tree. Angiography could detect significant hemobilia in over 90% of patients[13], and allow the localization of vascular lesions and therapeutic embolization.

The management of hemobilia is aimed at stopping the bleeding and relieving biliary obstruction. Transarterial embolization is now the first line of intervention to stop the bleeding of hemobilia, which returned a high success rate of around 80% to 100%[1], and lower morbidity or mortality rates than surgery[14]. Surgical interventions, such as ligation of the bleeding vessel or excision of the aneurysm, should be considered if embolization fails or is contraindicated.

In conclusion, hemobilia is one of the causes of obscure gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Although iatrogenic cases have replaced traumatic ones as the major type of hemobilia, one should keep in mind that ascending cholangitis is a possibility and may sometimes be complicated by life-threatening hemobilia. In particular, the rupture of a hepatic artery aneurysm should be taken into consideration in patients with a remote history of endoscopic or surgical sphincterotomy.