Published online Dec 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2876

Revised: September 20, 2003

Accepted: October 23, 2003

Published online: December 15, 2003

A 95-year old gentleman developed fatal icteric flare of chronic hepatitis B despite lamivudine treatment. This article highlights the atypical presentations of chronic hepatitis B in elderly patient and the need to consider this possibility for acute fulminant hepatitis in endemic areas.

- Citation: Wong W, Leung WK, Chan HLY. Icteric flare of chronic hepatitis B in a 95-year old patient. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(12): 2876-2877

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i12/2876.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2876

A 95-year old gentleman was admitted in July 2003 for decreased appetite and reduced mobility. He enjoyed good past health and had no history of hepatitis or jaundice. Two weeks prior to admission, family members noted that he became drowsier and refused food. He was living at home with family and had no history of percutaneous exposure before admission. He had never had tattooing, blood transfusion, casual sex or illicit drug use. There was no traveling history for more than twenty years. The patient was not on any medication or herbs.

On admission, the patient was barely arousable. He could only answer simple questions. He was in deep jaundice and dehydrated. There was no stigma of chronic liver disease. Abdominal examination did not reveal any tenderness, organomegaly or ascites. Flapping tremor could not be demonstrated because the patient was in grade 3 hepatic encephalopathy.

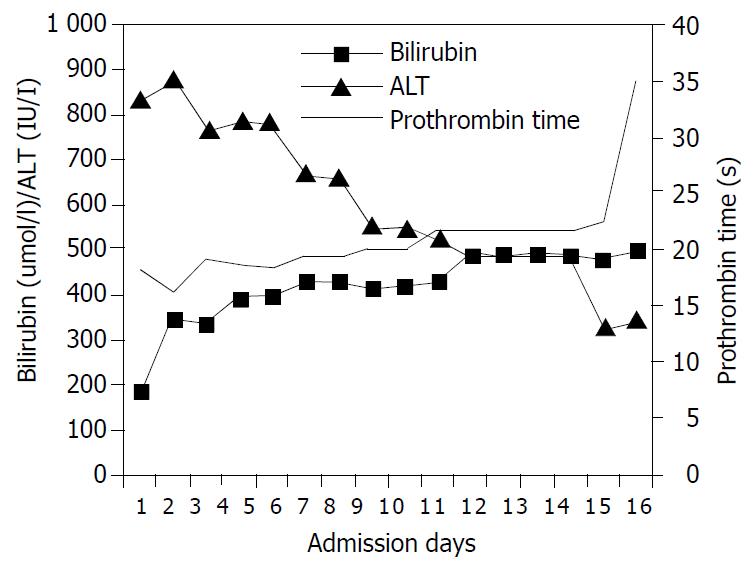

Blood test results were compatible with the picture of severe hepatitis. The serum bilirubin level was 188 μmol/l, alkaline phosphatase was 76 IU/l (normal 40-100 IU/l), and alanine aminotransferase was 825 IU/l (normal < 58 IU/l). The prothrombin time was prolonged at 18.1 seconds. Platelet count was 86 × 109/l. Renal function was normal. Urgent ultrasound scan showed normal liver echotexture and normal size spleen. The biliary trees were normal. There was no gallstone.

His hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) was positive, IgM anti-hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) was equivocal, hepatitis B e-antigen was negative, and antibodies to hepatitis B e-antigen (anti-HBe) was positive. Hepatitis B virus DNA was 97.9 × 106 copies/ml by TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction[1]. The serology tests for hepatitis A, C, D and E viruses were negative.

Lamivudine 100 mg daily was commenced on the fourth day of admission, and supportive treatment with vitamin K, lactulose and intravenous fluids replacement were prescribed. While the level of alanine aminotransferase was on decreasing trend, serum bilirubin and prothrombin time gradually increased (Figure 1). He developed progressive liver failure with worsening hepatic encephalopathy and eventually succumbed sixteen days after admission.

This case illustrates an unusual presentation of severe hepatitis B virus infection at an advanced age. Although liver biopsy has not been performed, other causes of acute hepatitis have been excluded by negative drug history and negative serology tests for other hepatitis viruses. The absence of risky percutaneous exposure renders the possibility of acute hepatitis B very unlikely. As a majority of chronic hepatitis B patients are asymptomatic and most people in Hong Kong do not have regular health check-up, it is most likely that this patient was suffering from chronic hepatitis B with HBsAg first discovered to be positive at this presentation. Equivocal IgM anti-HBc test is not diagnostic of acute hepatitis B but could also be detected in severe reactivation of chronic hepatitis B[2].

According to most prospective series, reactivation of chronic hepatitis B typically occurred at around the second and third decades[3-5]. Once a patient develops HBeAg seroconversion to anti-HBe, the durability reaches eighty percent. Patients often have quiescent disease afterwards, and the risks of complications, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis, are considerably reduced. Our patient probably has achieved sustained HBeAg seroconversion and disease remission several decades before this admission as he had negative HBeAg and no sign of liver cirrhosis at the age of 95. Reactivation of chronic hepatitis B causing jaundice and liver failure at this advanced age is uncommon. This case illustrates the importance to consider chronic hepatitis B as a cause of liver function derangement in endemic areas such as Asia.

Icteric reactivation of chronic hepatitis B carries a poor prognosis even with lamivudine treatment. In a series of 46 patients with severe reactivation of chronic hepatitis B with jaundice a quarter of patients died or required liver transplantation[6]. When both independent predictors of liver-related mortality including thrombocytopenia (platelet count below 143 × 109/l) and hyperbilirubinemia (serum bilirubin greater than 172 μmol/l) are present, as in our case, the mortality rate is up to 69.2%.

In conclusion, despite atypical presentation and atypical age group, chronic hepatitis B should be considered in cases of acute fulminant hepatitis in endemic areas.

Edited by Wang XL

| 1. | Chan HL, Chui AK, Lau WY, Chan FK, Wong ML, Tse CH, Rao AR, Wong J, Sung JJ. Factors associated with viral breakthrough in lamivudine monoprophylaxis of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. J Med Virol. 2002;68:182-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maruyama T, Schödel F, Iino S, Koike K, Yasuda K, Peterson D, Milich DR. Distinguishing between acute and symptomatic chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1006-1015. [PubMed] |

| 3. | McMahon BJ, Holck P, Bulkow L, Snowball M. Serologic and clinical outcomes of 1536 Alaska Natives chronically infected with hepatitis B virus. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:759-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lok AS, Lai CL, Wu PC, Leung EK, Lam TS. Spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen to antibody seroconversion and reversion in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1839-1843. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Liaw YF, Chu CM, Lin DY, Sheen IS, Yang CY, Huang MJ. Age-specific prevalence and significance of hepatitis B e antigen and antibody in chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Taiwan: a comparison among asymptomatic carriers, chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol. 1984;13:385-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chan HL, Tsang SW, Hui Y, Leung NW, Chan FK, Sung JJ. The role of lamivudine and predictors of mortality in severe flare-up of chronic hepatitis B with jaundice. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:424-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |