Published online Dec 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2873

Revised: September 10, 2003

Accepted: October 12, 2003

Published online: December 15, 2003

AIM: Gastric outlet obstruction caused by duodenal impaction of a large gallstone migrated through a cholecystoduodenal fistula has been referred as Bouveret’s syndrome. Endoscopic lithotomy is the first-step treatment. However, surgery is indicated in case of failure or complication during this procedure.

METHODS: We report herein an 84-year-old woman presenting with features of gastric outlet obstruction due to impacted gallstone. She underwent an attempt of endoscopic retrieval which was unsuccessful and was further complicated by distal gallstone ileus. Physical examination was irrelevant.

RESULTS: Endoscopy revealed multiple erosions around the cardia, a large stone in the second part of the duodenum causing complete obstruction, and wide ulceration in the duodenal wall where the stone was impacted. Several attempts of endoscopic extraction by using foreign body forceps failed and surgical intervention was mandatory. Preoperative ultrasound evidenced pneumobilia whilst computerized tomography showed a large stone, 5 × 4 × 3 cm, logging at the proximal jejunum and another one, 2.5 × 2 × 2 cm, in the duodenal bulb causing closed-loop syndrome. She underwent laparotomy and the jejunal stone was removed by enterotomy. Another stone reported as located in the duodenum preoperatively was found to be present in the gallbladder by intraoperative ultrasound. Therefore, cholecystoduodenal fistula was broken down, the stone was retrieved and cholecystectomy with duodenal repair was carried out. She was discharged after an uneventful postoperative course.

CONCLUSION: As the simplest and the least morbid procedure, endoscopic stone retrieval should be attempted in the treatment of patients with Bouveret’s syndrome. When it fails, surgical lithotomy consisting of simple enterotomy may solve the problem. Although cholecystectomy and cholecystoduodenal fistula breakdown is unnecessary in every case, conditions may urge the surgeon to perform such operations even though they carry high morbidity and mortality.

- Citation: Gencosmanoglu R, Inceoglu R, Baysal C, Akansel S, Tozun N. Bouveret’s syndrome complicated by a distal gallstone Ileus. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(12): 2873-2875

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i12/2873.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2873

Gallstones are completely asymptomatic in the majority of patients (60%-80%)[1]. When they become symptomatic, biliary colic is the most frequently encountered manifestation. Patients with mild symptoms have a higher risk of developing gallstone-related complications such as acute cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis with or without cholangitis, gallstone pancreatitis or gallstone ileus[2]. Biliary fistula occurs in 3% to 5% of the cases[3]. Gallstones can migrate into the terminal ileum through a cholecystoduodenal fistula and cause an intestinal obstruction at this level but they may also anchor at the duodenum and produce the symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction in rare cases as first described by Bouveret in 1893[4]. Since this syndrome is usually observed in older patients with poor medical status, a non-surgical approach such as endoscopic stone removal has been used as the first-line treatment. This may be performed by simple endoscopic lithotomy with snare or specific stone baskets designed for endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography. When feasible, stones are attempted to fragment into small pieces followed by endoscopic removal. Laser lithotripsy either with percutaneous or transendoscopic routes and extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) are the alternative treatment modalities[5-7]. In the case of unsuccessful stone removal or its distal migration resulting in mechanical intestinal obstruction, particularly with larger stones, these techniques may be ineffective and surgery may be needed. The main purpose of surgical intervention should be to remove the obstructing stone by enterotomy without cholecystectomy and cholecystoduodenal fistula breakdown to minimize the risks of surgery. However, when it is necessary as the case presented hereby, gallbladder excision can be performed successfully.

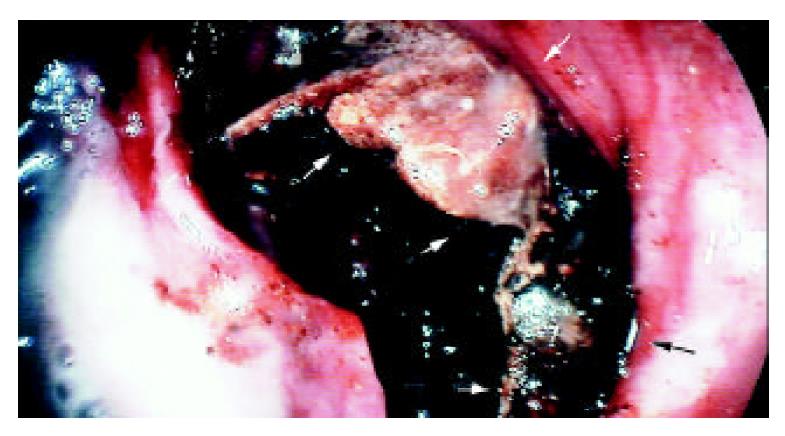

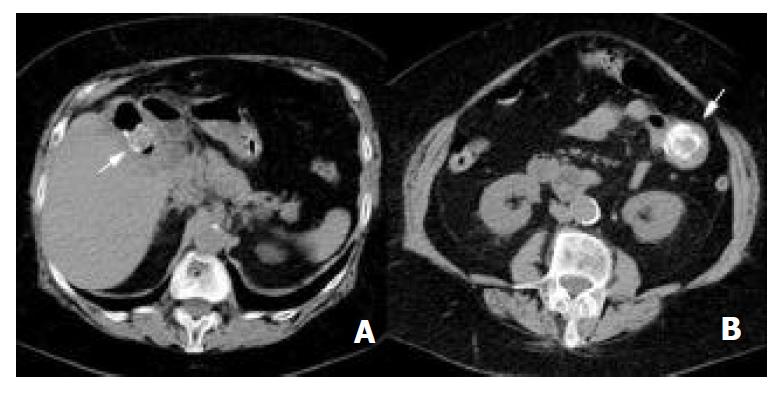

An 84-year-old woman presenting with 5 days of nausea and vomiting, hematemesis, loss of appetite, and a severe upper abdominal pain located to the periumbilical region was admitted to the emergency unit of the Marmara University Institute of Gastroenterology and referred to Acibadem Hospital according to her will. The physical examination did not show remarkable abdominal distention or any changes in bowel sounds. Abdominal ultrasound evidenced pneumobilia but the gallbladder was not visualized due to excess gas related to gastric and duodenal dilatation. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed multiple erosions around the cardia, ascribed to Mallory-Weiss syndrome, a large stone in the second part of the duodenum causing complete obstruction, and wide ulceration in the duodenal wall where the stone was impacted (Figure 1). Although, no clear cholecystoduodenal fistula was demonstrated endoscopically, the typical appearance of the stone indicated its gallbladder origin. Attempts for mechanical fragmentation and retrieval of the stone at the same endoscopic session were unsuccessful. Computerized tomography of the abdomen showed pneumobilia, remarkable distention of stomach, and a 5 cm mass with a calcified rim in the jejunum (Figure 2A). Another mass of 2.5 cm in diameter, sharing similar radiologic features at the right upper abdominal quadrant (Figure 2B) was reported by radiologists as a second gallstone obstructing the duodenal lumen and resulting in a closed-loop syndrome.

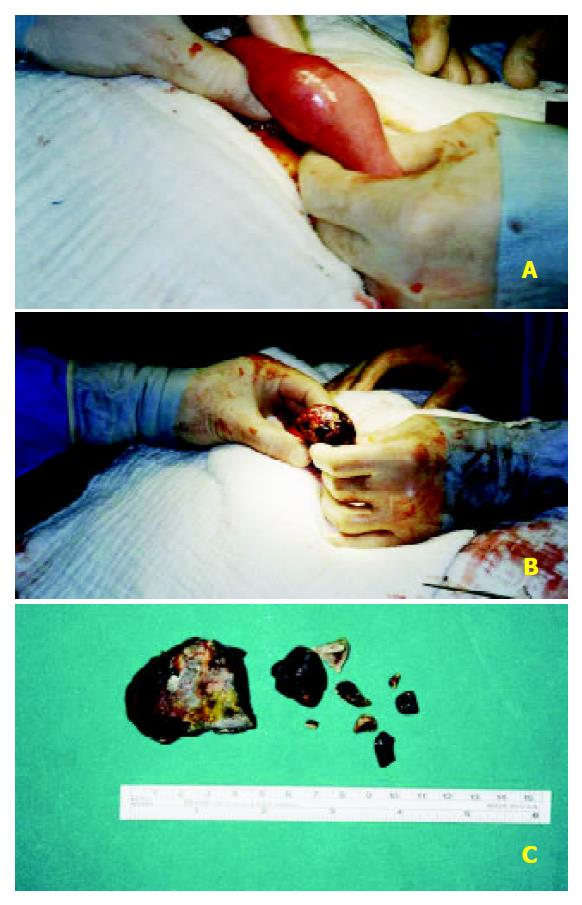

The features of the stone, the failure of endoscopic retrieval and the general status of the patient urged to undertake a surgical lithotripsy by laparotomy and enterotomy. At laparotomy, the stone was palpated in the jejunum about 15 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz with a complete mechanical obstruction which was easily diagnosed with the presence of remarkable dilation of the proximal jejunal segment (Figure 3A). There were dense adhesions between the gallbladder and the duodenum, greater omentum, and right part of the transverse colon. The jejunum was opened and the large stone was removed (Figure 3B). Two small pieces of the stone were also removed from the proximal lumen (Figure 3C).

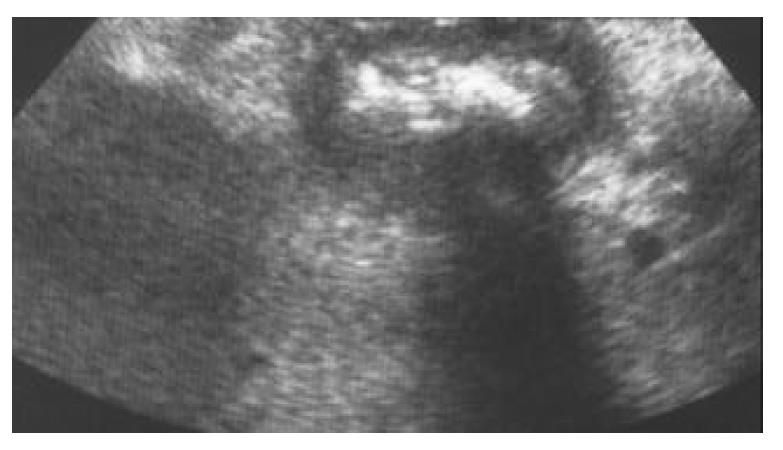

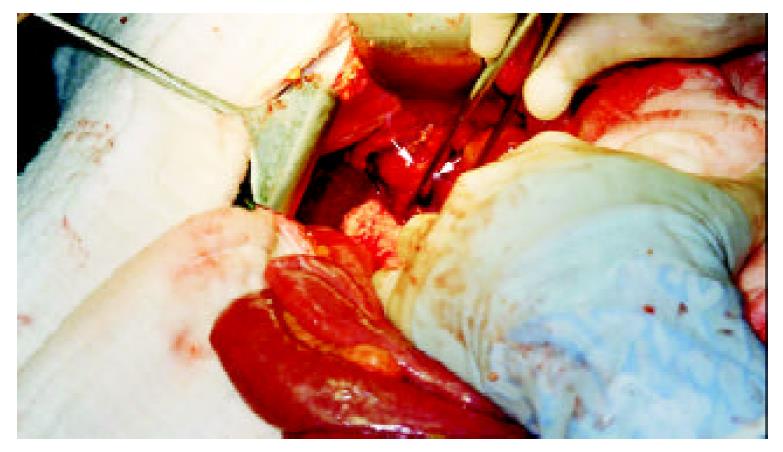

Then the jejunum was primarily closed with double-layer running stitches of an absorbable material. Since the location of the other stone could not be detected by palpation and the subsequent operative strategy was dependent on its site, an intra-operative ultrasound was performed (Figure 4). Once the other stone was shown to be located in the gallbladder lumen, a cholecystectomy and a duodenal repair was undertaken to avoid further migration of the retained large fragment of the stone which would result in intestinal obstruction. Hence the gallbladder was opened, cholecystoduodenal fistula was broken down, and the stone was retrieved from the lumen followed by antegrade cholecystectomy (Figure 5). Duodenal lumen was also cleared from small stone fragments (Figure 3C) then the duodenal opening was closed by a transverse single-layer running stitch of an absorbable material. The post-operative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the eighth postoperative day. She has been symptom-free in the 3-month period of follow-up.

Bouveret’s syndrome as described by gastric outlet obstruction caused by a large gallstone passing into the duodenal bulb through a biliogastric or bilioduodenal fistula usually develops in older patients with poor medical conditions and surgical treatment consisting of cholecystectomy and duodenal repair following extraction of the stone through the broken-down cholecystoduodenal fistula or a separate duodenotomy results in considerable morbidity and mortality[8]. Developments in surgical techniques have reduced the reported mortality rate of 30% before 1968 to 12% in recent years. Accordingly, surgical aim has gradually shifted from a radical procedure in which the gallbladder is removed and the cholecystoduodenal fistula is repaired to a simple approach consisting of enterotomy and stone extraction. Alternatives to surgical lithotomy such as simple endoscopic lithotomy and laser or ESWL have been reported with successful outcomes in some cases[5].

Bouveret’s syndrome was reported to occur more frequently in females (65%) with a median age of 69 years. Diagnosis is made usually during the upper GI endoscopy further supported by abdominal ultrasound findings. Computerized tomography is helpful in demonstrating the exact level of obstruction, the biliary site of duodenal fistula, and the status of gallbladder especially in cases of gallbladder rupture. Endoscopic lithotomy is the first line approach to treatment; however, it may be unsuccessful in some cases particularly with impacted large stones. Stones, usually larger than 2.5 cm in diameter, have been reported in cases with Bouveret’s syndrome[3]. Smaller stones generally pass through the duodenum and do not cause gastric outlet obstruction. Endoscopic extraction of stones up to 3 cm in size has been reported[3]. However, larger stones usually get impacted in the duodenum and cause an ischemic ulceration on its wall. On the other hand, large gallstones of mixed type tend to have a very hard outer shell, even though their core may be softer[5]. This feature may hamper their mechanical fragmentation with endoscopic forceps. Although these large stones can be broken down by ESWL, the irregular shape and the relatively large sizes of the fragments may hinder their passage to distal bowel, especially in the case of impacted stones. Percutaneous laser lithotripsy or Holmium: YAG laser via a flexible optic fiber through the working-channel of the endoscope, as recently reported by Alsolaiman et al[5], do not always result in success. In addition, the non-availability of these expensive equipments in most centers restricts their wide-spread use.

Many cases have been reported with migration of the stone after unsuccessful attempts of endoscopic stone extraction or alternative lithotripsy methods. When un-fragmented stone migrates into the small bowel, its removal by a simple enterotomy is easily done. Enterotomy carries less morbidity rate when compared to duodenotomy particularly in patients with duodenal ulcer due to the erosion of duodenal wall by an impacted large stone. When the stone is broken down into several pieces by non-surgical methods and pieces are removed endoscopically, larger fragments which migrate distally can cause obstruction and require surgery. Intraoperative endoscopy may facilitate recognition and removal of remaining stones in the proximal gastrointestinal lumen. However, the presence of any remaining stone fragments in the gallbladder may critically raise the question whether the cholecystectomy is necessary or not. In the present case, the large piece of the gallstone was removed by enterotomy, but the presence of a remaining fragment, which was 2.5 cm in diameter in the gallbladder, necessitated cholecystectomy and cholecystoduodenal fistula breakdown in order to avoid any further attack as it has been reported in similar cases in the literature.

Intraoperative ultrasound is advised in cases where the surgeon is unable to localize exactly the site of the remaining stone fragments. In our case, although radiologists preoperatively reported the second stone fragment as situated in the duodenum causing closed-loop syndrome with a larger one located more distally, intraoperative ultrasound showed the remaining fragment still in the gallbladder. This finding changed our operative strategy from a simple enterotomy and stone extraction to a more complicated procedure such as cholecystectomy and duodenal wall repair.

In summary, endoscopic lithotripsy and stone extraction should be performed as a first-step treatment in patients with Bouveret’s syndrome. When it fails, surgical lithotomy consisting of simple enterotomy may solve the problem. Although cholecystectomy and cholecystoduodenal fistula breakdown is not recommended routinely, especially when the patient’s age and clinical status limit a more aggressive approach, they can be performed successfully when conditions force the surgeon to undertake such a decision.

Edited by Zhu LH

| 1. | Haris HW. Biliary system. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, Lowry SF, Mulvihill SJ, Pass HI, Thompson RW, eds. Sur-gery Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag. 2001;553-584. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ahrendt SA, Pitt HA. Biliary tract. In: Townsend CM Jr, Editor-in-Chief. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. Section X. Abdomen. 16th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. 2001;1076-1111. |

| 3. | Salah-Eldin AA, Ibrahim MA, Alapati R, Muslah S, Schubert TT, Schuman BM. The Bouveret syndrome: an unusual cause of hematemesis. Henry Ford Hosp Med J. 1990;38:52-54. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Nielsen SM, Nielsen PT. Gastric retention caused by gallstones (Bouveret's syndrome). Acta Chir Scand. 1983;149:207-208. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Alsolaiman MM, Reitz C, Nawras AT, Rodgers JB, Maliakkal BJ. Bouveret's syndrome complicated by distal gallstone ileus after laser lithotropsy using Holmium: YAG laser. BMC Gastroenterol. 2002;2:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ondrejka P. Bouveret's syndrome treated by a combination of extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) and surgical intervention. Endoscopy. 1999;31:834. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Maiss J, Hochberger J, Muehldorfer S, Keymling J, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Successful treatment of Bouveret's syndrome by endoscopic laserlithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1999;31:S4-S5. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Malvaux P, Degolla R, De Saint-Hubert M, Farchakh E, Hauters P. Laparoscopic treatment of a gastric outlet obstruction caused by a gallstone (Bouveret's syndrome). Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1108-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |