Published online Dec 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2706

Revised: August 27, 2003

Accepted: October 12, 2003

Published online: December 15, 2003

AIM: Lymphocytic gastritis is commonly associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. The presence of glandular atrophy and foveolar hyperplasia in lymphocytic gastritis suggests abnormalities in cell proliferation and differentiation, forming a potential link with the suspected association with gastric cancer. Our aim was to compare epithelial proliferation and morphology in H pylori associated lymphocytic gastritis and H pylori gastritis without features of lymphocytic gastritis, and to evaluate the effect of H pylori treatment.

METHODS: We studied 14 lymphocytic gastritis patients with H pylori infection. For controls, we selected 14 matched dyspeptic patients participating in another treatment trial whose H pylori infection had successfully been eradicated. Both groups were treated with a triple therapy and followed up with biopsies for 6-18 months (patients) or 3 months (controls). Blinded evaluation for histopathological features was carried out. To determine the cell proliferation index, the sections were labeled with Ki-67 antibody.

RESULTS: Before treatment, lymphocytic gastritis was characterized by foveolar hyperplasia (P = 0.001) and glandular atrophy in the body (P = 0.008), and increased proliferation in both the body (P = 0.001) and antrum (P = 0. 002). Proliferation correlated with foveolar hyperplasia and inflammation activity. After eradication, the number of intraepithelial lymphocytes decreased in the body (P = 0.004) and antrum (P = 0.065), remaining higher than in controls (P < 0.001). Simultaneously, the proliferation index decreased in the body from 0.38 to 0.15 (P = 0.043), and in the antrum from 0.34 to 0.20 (P = 0.069), the antral index still being higher in lymphocytic gastritis than in controls (P = 0.010). Foveolar hyperplasia and glandular atrophy in the body improved (P = 0.021), reaching the non-LG level.

CONCLUSION: In lymphocytic gastritis, excessive epithelial proliferation is predominantly present in the body, where it associates with foveolar hyperplasia and glandular atrophy. These characteristic changes of lymphocytic gastritis are largely related to H pylori infection, as shown by their improvement after eradication. However, some residual deviation was still seen in lymphocytic gastritis, indicating either an abnormally slow improvement or the presence of some persistent abnormality.

-

Citation: Mäkinen JM, Niemelä S, Kerola T, Lehtola J, Karttunen TJ. Epithelial cell proliferation and glandular atrophy in lymphocytic gastritis: Effect of

H pylori treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(12): 2706-2710 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i12/2706.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2706

Lymphocytic gastritis (LG) is an inflammatory disorder first described by Haot and his group in 1985[1]. This histopathological entity is characterized by a marked increase in the number of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), most being CD8+ or CD3+ cytotoxic T-cells[2]. The amount of 25 IELs per 100 epithelial cells is usually considered diagnostic[3]. The reported prevalence of LG among patients with dyspepsia varies between 1%-8%[4,5]. Most dyspeptic patients with LG are seropositive for Helicobacter pylori, indicating that LG may represent an atypical host immune response to the infection[6]. Cases associated with H pylori infection have been reported to respond to H pylori eradication treatment[7-9]. Gluten is one of the other suspected trigger factors in particular cases, and the prevalence of LG is high in patients with celiac disease, reaching levels up to 45% in some series[10,11].

LG is common in patients with gastric carcinoma and gastric MALT lymphoma, suggesting that it may be pathogenetically related to gastric malignancies[12,13]. However, mechanisms linking LG with malignancy are not known. Atrophic changes and foveolar hyperplasia in the body mucosa are common in LG, suggesting that abnormal epithelial proliferation and differentiation may be present. Without treatment these abnormalities are usually considered to be persistent[5]. Furthermore, our previous follow-up study has shown that LG is linked to a tendency of more severe progression of intestinal metaplasia than in H pylori gastritis without LG[5].

Since foveolar hyperplasia is a characteristic of lymphocytic gastritis, we hypothesized that this might be associated with abnormal proliferation rate. In addition to testing this hypothesis by comparing the proliferation rate with non-LG H pylori gastritis, we evaluated the effect of H pylori treatment on epithelial cell proliferation and other histopathological features of LG, including glandular atrophy, to find out whether the abnormalities are related to H pylori infection and whether they are irreversible.

Two separate series of patients were studied with some differences in the treatment and follow-up protocol. Patients with LG were collected from among the out-patients referred to one endoscopist (SN) for upper abdominal complaints. Patients with histologically proven LG and either histologically or serologically confirmed H pylori infection were subsequently included in the open study, in which their H pylori infection was treated and they were invited to take part in the post-treatment examinations to document the effects of H pylori eradication. An informed consent was obtained from all the patients according to the usual clinical practice. A total of 14 patients (six men, eight women; mean age 55.2 years, range 41-70 years) who fulfilled the criteria were included. Originally all of them were seropositive for H pylori, while only three patients (21%) could be confirmed as positive on histology. All of the patients had normal findings in duodenal biopsy; no subjects with celiac disease were included. Follow-up gastroscopies with gastric biopsies were performed on all the patients after the eradication. The mean follow-up time was 12 months, ranging from six to 18 months. The effect of treatment on intraepithelial lymphocyte counts in a subset of these patients has been previously reported[9].

For the control group, a series of age and gender matched H pylori positive subjects were selected from another treatment trial: Prospective Phase IV clinical multicenter study aiming at testing the effects of sucralfate as an adjuvant to H pylori eradication therapy in non-ulcer dyspepsia (F-SUC-CL-0191-FIN; Orion Corporation, Orion Pharma, Finland). Inclusion criteria included the following: age over 18 years, dyspeptic symptoms not explained by any other disease, normal upper abdominal ultrasound, no active peptic ulcer or a history of ulcer, no endoscopic esophagitis, no other severe illness, no need for continuous use of NSAID or steroids. The patients were not allowed to use any anti-ulcer drugs including antacids or H2-antagonists during the two weeks before the trial. The study was approved by the ethical committees in the participating hospitals in Northern Finland. Only subjects with a successful eradication result based on histology were selected. The control group consisted of 14 patients (seven men, seven women, mean age 53.8 years, range 38-67 years) all presenting with H pylori positive gastritis without either LG, celiac disease or malignancy. Biopsies taken before the treatment and three months after the eradication therapy were studied.

A minimum of two biopsies was taken from both the antrum and the body at the initial and follow-up gastroscopy. In addition, routine biopsies from the descending part of the duodenum were taken during the primary endoscopy. The biopsies were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. During the collection of the patient series one pathologist (TKa) made a preliminary diagnosis of LG. The diagnosis was based on the presence of intraepithelial lymphocytes at a ratio of 30 per 100 epithelial cells, or greater, in the areas of their maximal density.

After the follow-up of the whole series was completed, the slides were coded and evaluated for IEL counts by a second pathologist (TKe), blinded for any clinical data including treatment status and the results of preliminary histopathological evaluation. The IEL number was counted at three randomly selected fields of surface and foveolar epithelium separately in the antral and body mucosa. In addition, IEL number was counted in the area of the maximal IEL density in antral and body mucosa. Around 100 to 150 cells in epithelium were counted in each field. The grade of gastritis, quantity of different types of inflammatory cells, grade of atrophy, foveolar hyperplasia and intestinal metaplasia were similarly analyzed by a blinded investigator (TKa) according to the histological criteria of the updated Sydney system. The presence and quantity of H pylori was evaluated from sections stained with a modified Giemsa stain.

Sections from each gastric biopsy specimen were treated with 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 2 x 5 minutes for antigen retrieval. The sections were incubated with Ki-67 monoclonal antibody (clone 7B11, Zymed, South San Francisco, CA, USA; 1:50 dilution) for 60 minutes at 37 °C. Bound antigen was detected with labeled streptavidin-biotin method using AEC as a chromogen (HistostainTM–plus, Zymed, South San Francisco, CA, USA). Hematoxylin was used as a counterstain.

Labeled and unlabeled epithelial cells were counted under a high-power microscope (×100) in the optimal, longitudinally orientated and complete foveolae. The proportion of positive cells among foveolar epithelial cells indicated the proliferation (labeling) index (LI%). The mean LI% for each biopsy was calculated as an average from several foveolae. The counting was performed by a single person (JM) blinded for all previous clinical and histopathological data.

The serological diagnosis of H pylori was made by testing the specific IgG antibodies with an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, PylorisetR, Orion Diagnostica, Finland). Titers of 1:500 or higher were considered positive.

In the LG group, H pylori eradication therapy consisted of a ten day course of bismuth subsitrate (240 mg twice daily) and metronidazole (400 mg three times daily) or amoxycillin (1 g twice daily). The controls were treated for two weeks with metronidazole (400 mg three times daily) and tetracycline (500 mg three times daily). In addition they got sucralfate (2 g twice daily for 6 weeks followed by 1 g once daily for 6 weeks). No proton inhibitors were allowed in the control group.

LG patients and controls were compared by using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Temporal changes in the results were evaluated by using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Spearman’s two-tailed rank correlation test was used to assess the correlations between the variables. A probability of P less than 0.05 in two-tailed tests was considered statistically significant. Analyses were made with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 10.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

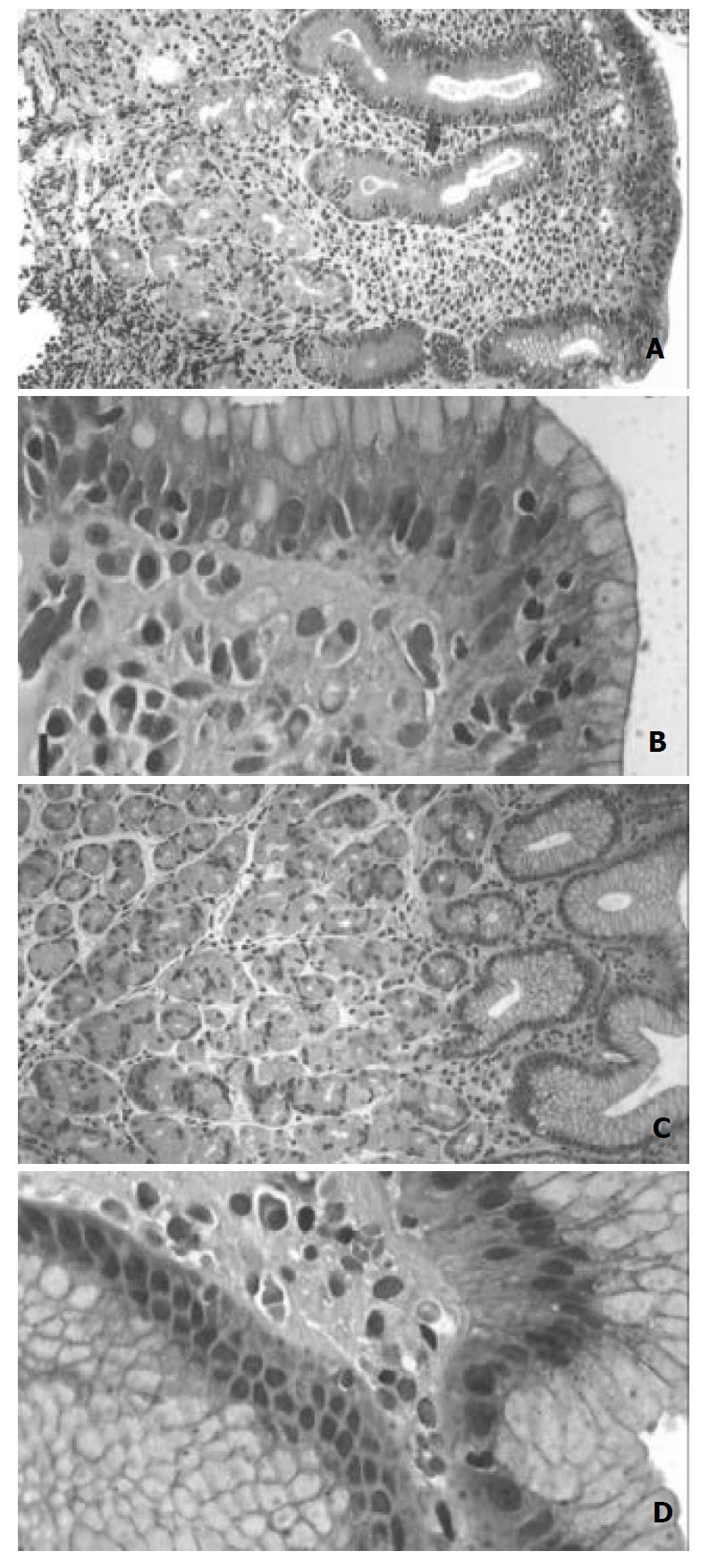

In all the patients with LG the maximal number IELs was 30 IEL/100 epithelia in either the body or antral mucosa. The histopathological features including the IEL density (per 100 epithelial cells) in random fields. (Table 1; Figure 1) and epithelial cell proliferation (Figure 2) before eradication treatment were compared between LG and non-LG H pylori gastritis. The density of H pylori organisms was higher in the control group in the body (P = 0.009) and antral mucosa (P = 0.001), and showed a significant negative correlation with age in LG (body mucosa; c = -0.633, P = 0.002). The pre-treatment levels of specific IgG antibody titers were lower in the control group (median 1:1575, range 1:140-1:5600) than in LG (1:6000, range 1:1000-1:17000; P = 0.011).

| Antrum | LG | Non-LG | Body | LG | Non-LG |

| H pylori score | 0 (0-2)f | 2 (0-3)bf | H pylori score | 0 (0-3)d | 2 (0-3)bd |

| After treatment | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0)b | After treatment | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0)b |

| Atrophy | 2 (1-2) | 2 (0-3) | Atrophy | 2 (1-3)ad | 1 (0-2)d |

| After treatment | 1 (1-2) | 2 (0-3) | After treatment | 1 (1-2)a | 1 (0-2) |

| Metaplasia | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-1) | Metaplasia | 0 (0-2)d | 0 (0-0)d |

| After treatment | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | After treatment | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) |

| Foveolar length (μm) | 340 (290-650)a | 300 (260-370) | Foveolar length (μm) | 310 (250-800)bf | 170 (130-210) |

| After treatment | 300 (250-330)a | 320 (220-480) | After treatment | 210 (140-290)b | 200 (150-320) |

| IEL count (mean) | 9.5 (1.0-30.7)f | 1.7 (1.0-4.0)f | IEL count (mean) | 26.3 (3.7-56.7)bf | 1.7 (0.3-2.7)f |

| After treatment | 5.7 (0.7-11.0) | 1.3 (0.3-3.7) | After treatment | 5.7 (1.0-41.7)bf | 2.0 (0.3-3.7)f |

| Activity | 1 (0-2)ad | 2 (0-3)ad | Activity | 1 (0-2)a | 0.5 (0-2)a |

| After treatment | 0 (0-0)ad | 0 (0-2)ad | After treatment | 0 (0-2)a | 0 (0-1)a |

| Eosinophils | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | Eosinophils | 1 (1-2)af | 1 (0-1)f |

| After treatment | 0 (0-1)d | 1.5 (0-3)d | After treatment | 1 (0-2)ad | 0 (0-1)d |

In the antral mucosa the degree of atrophy did not show any significant differences between LG and non-LG H pylori gastritis, but the body mucosa showed significantly more severe atrophy in LG (Table 1; P = 0.008). Of LG subjects 50% (n = 7) showed mild and 14% (n = 2) moderate atrophy of the body mucosa (Figure 1), while 36% (n = 5) showed no sign of atrophy. No cases with severe atrophy were found. The severity of atrophy in the body showed a trend towards a positive association with IEL count (c = 0.542, P = 0.069). In the control group, only 17% (n = 2) of the cases showed atrophy of the body mucosa prior to eradication. In the antrum, gastritis was more active in the controls (P = 0.034), but no significant difference was seen in the body. The eosinophilic leukocytes score in the body mucosa was higher in LG (Table 1; P = 0.001), while in the antral mucosa the score tended to be higher in the control group (P = 0.062). The extent of intestinal metaplasia in the body mucosa tended to be greater in LG (Table 1; P = 0.095). Elongation of the foveolae was more often seen in LG (Table 1; Figure 1; body mucosa P = 0.001; antral mucosa P = 0.074.)

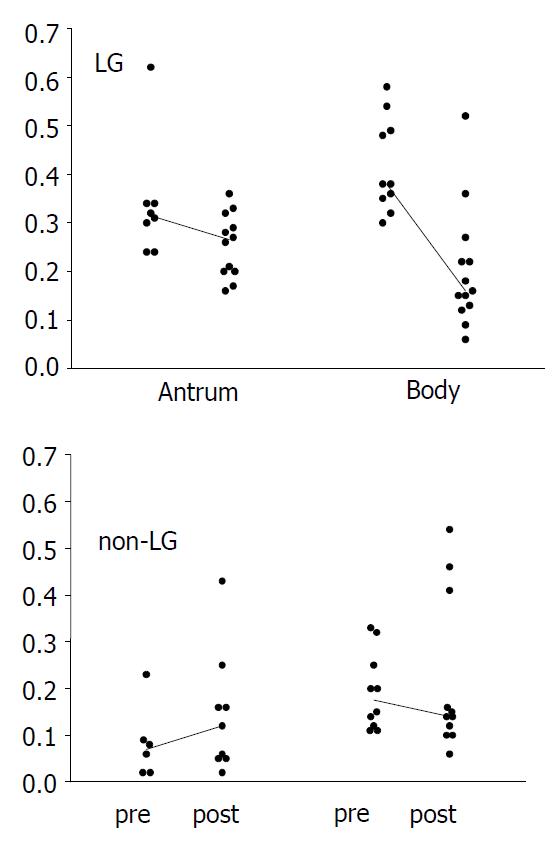

Due to tangential sectioning, the proliferation index based on the number of cells with nuclear expression of Ki-67 could be determined in only about 80% of the specimen slides. The pre-treatment epithelial cell proliferation rate was higher in LG in both the body (P = 0.001) and antral mucosa (P = 0.002) compared to the controls (Figure 1). In LG, the proliferation index of the body mucosa showed correlation with the degree of foveolar hyperplasia (c = 0.798, P = 0.010), but did not correlate with atrophy or any other histologic feature, except for a trend towards correlation with the activity of gastritis (c = 0.655, P = 0.078). In the antral mucosa the proliferation index correlated negatively with the patient’s age (c = -0.707, P = 0.050). In the controls, proliferation showed no significant correlation with any of the histological markers or age.

We then analyzed what kind of impact the eradication treatment had on cell proliferation and gastritis in LG patients and controls. In LG, successful eradication could be verified in 12 out of 14 patients. All the three patients initially positive on histology were now found to be H pylori negative, and showed a decrease of 50% or more in titer of specific IgG antibodies. Nine cases initially negative on histology showed a similar decrease in their antibody titers, thus indicating a successful eradication. In two patients, both negative on histology, the decrease in the IgG titers did not quite reach 50%. However, on histological evaluation of the inflammation, these two patients showed a similar shift towards normal mucosal morphology as the other LG patients. In the control group, all cases were successfully eradicated and turned histologically negative. Yet on serology, only five non-LG patients showed a decrease of the IgG titer of 50% or more.

In LG, the proliferation index decreased significantly after the eradication in the body mucosa (Figure 2; median from 0.38 to 0.15, P = 0.043), and showed a similar trend in the antrum (from 0.34 to 0.20, P = 0.069). In controls, no significant changes were seen (Figure 2). The post-eradication proliferation index in the antrum was nonetheless significantly higher in LG patients (P = 0.010).

The IEL number decreased significantly in LG (Figure 1) both in areas of maximal density (data not shown) and in random fields (Table 1; body, P = 0.004), but no change was seen among controls. The post-eradication IEL counts were still significantly higher in LG compared to the controls (Table 1; P < 0.001). The overall score of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria decreased significantly in both groups (Table 1). In LG, glandular atrophy of the body mucosa improved significantly (P = 0.021; Figure 1), and after the treatment most subjects (83%) showed no atrophy at all. Two cases had mild atrophic changes at this stage. However, such a change could not be observed in the antrum. In the control group, eradication did not have any effect on the degree of atrophy in the body (Table 1; P = 0.564) or in the antrum (P = 0.783). In LG, a significant shallowing of the gastric pits was seen, as evidence of reduction in the foveolar hyperplasia (body, P = 0.005; antrum, P = 0.050). No significant changes were observed in controls.

Since both the IEL counts and proliferation remained significantly increased in LG, we searched for any correlation with inflammatory cell scores to see whether these features were related to residual inflammation, or possibly inherently abnormal. No significant correlations were seen in either antral or body mucosa between neutrophil, eosinophil or mononuclear inflammatory cell scores, but in the body the proliferation index showed a significant correlation with the IEL count (c = 0.779, P = 0.005). In controls, the proliferation index correlated similarly with the IEL number in the body mucosa (c = 0.654, P = 0.040).

In the present study we have shown that gastric epithelial cell proliferation rate, as measured by the Ki-67 labeling index, was increased in LG associated with H pylori infection as compared to H pylori gastritis without significant increase of intraepithelial lymphocytes. Increased proliferation was predominantly present in the body mucosa, where it was correlated with foveolar hyperplasia and inflammation activity. In addition, our results suggest that in LG, the characteristic increase of IELs, abnormal proliferation, and atrophic changes of the body mucosa are all largely related to H pylori infection, as shown by their improvement after eradication therapy.

Increased proliferation induced by the chronic inflammation has been observed in H pylori associated gastritis, and the proliferation rate seems in principal to normalize after eradication therapy[14], although the antral mucosa may retain a somewhat abnormal proliferation pattern[15]. In LG, according to our findings, neither the IEL counts nor cell proliferation fell to the level observed in controls after successful treatment, even though the follow-up time was longer in LG patients (minimum six months, mean 12 months) than in controls (three months). This slow rate of normalization is likely to be related to the more pronounced initial abnormality in LG, possibly necessitating a longer period of time for full recovery. A more extended follow-up might be needed to see if these subjects show any permanent abnormality in the proliferation rate. Some intrinsic malfunction causing either a constant abnormal epithelial lymphocyte response or proliferation, or both, is also possible, but no such defects have been reported in LG. A further possible explanation is that there is some other environmental factor in addition to H pylori inducing these changes, the effect of which continues after eradication. In some cases, LG is associated with celiac disease[10,11]. The present study included no patients with this disorder. Other nutritional factors could be involved, as in the duodenal mucosa where an increase of IELs has been described in food allergy[16]. No such antigen related changes in the gastric mucosa are yet known.

The controversy between the negative histology and positive serology for H pylori in LG in the present and previous studies[5,6,13] might be explained by the fact that the bacteria are present in very small numbers, which could make them impossible to detect. In the present study, even the patients histologically positive for H pylori showed only a small amount of bacteria. This is likely to be related to decreased acid secretion associated with the atrophic changes in the body mucosa, which have been shown to associate with a low number of bacteria and a shift of bacteria to the body mucosa[17] in a way similar to the effect of proton pump inhibitors[18]. A significant decrease of the specific antibodies after treatment, along with the improvement of the inflammatory changes, indicates that even the cases negative on histology represent a true H pylori infection. It is of interest that the levels of H pylori specific IgG antibodies were significantly higher in LG than in non-LG H pylori positive gastritis. This has been noted previously[5]. Whether the intensive serological response is related to a certain bacterial strain, amount of antigen, or a matter of a genetically determined pattern of immune response, is not known.

The mechanisms behind the processes of body glandular atrophy and foveolar hyperplasia in LG are unknown. The question of whether atrophy is based on an autoimmune reaction, metaplasia, fibrosis, or on a disturbance in cell regeneration or differentiation in connection with foveolar hyperplasia, needs further study, but the last alternative is most likely the correct one. We could not see any significant change in the extent of intestinal metaplasia after eradication. No auto-antibodies targeted against the gastric parietal cells have been found in LG patients (Niemelä et al unpublished observation), suggesting that autoimmune mechanisms are not important in the pathogenesis of body atrophy in LG. The gastric epithelial stem cells situated in the proliferation zone are capable of differentiating into the direction of either gastric glandular cells or foveolar epithelial cells[19]. It is unknown which mechanisms are involved in the actual regulation of the direction of differentiation. We speculate that in untreated LG, the cells in the foveolar border area have a greater stimulus for differentiation towards foveolar epithelial cells than towards glandular cells, this pressure eventually leading to glandular atrophy and foveolar hyperplasia. Thus LG might provide a model for studying the mechanisms of selection of epithelial cell differentiation.

A longstanding H pylori infection has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of gastric malignancies[20,21], and successful eradication of this pathogen resulted in the disappearance of histologically malignant lymphomatous proliferation[22]. Mechanisms of the suggested increased risk of malignancy in LG[12,13] are unknown. The increased epithelial cell proliferation rate, as detected in the present study, might play an important part by increasing the potential for the accumulation of genetic changes. Glandular atrophy as seen in the present study, and reported previously[5,13], forms another potential link for gastric cancer, since an increased cancer risk has been documented with body atrophy[23]. Without any treatment, atrophy and foveolar hyperplasia seen in LG are generally considered to be persistent, and even to progress at a faster rate than in subjects with a non-LG H pylori gastritis[5], supporting the idea that LG has pre-malignant potential. However, more studies are required to find out whether patients with LG are indeed at an increased risk of a gastric malignancy, and whether H pylori eradication reduces the risk of gastric neoplasia in these patients.

In conclusion, we have shown that the highly increased epithelial cell proliferation, predominantly in the body mucosa, is a characteristic feature of LG. Abnormal proliferation together with atrophic changes in the body mucosa in LG provide a potential mechanism for the observed association with gastric malignancy. Furthermore, these changes in LG are largely caused by H pylori infection as shown by their normalization by eradication therapy.

Edited by Zhu LH

| 1. | Haot J, Hamichi L, Wallez L, Mainguet P. Lymphocytic gastritis: a newly described entity: a retrospective endoscopic and histological study. Gut. 1988;29:1258-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Oberhuber G, Bodingbauer M, Mosberger I, Stolte M, Vogelsang H. High proportion of granzyme B-positive (activated) intraepithelial and lamina propria lymphocytes in lymphocytic gastritis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:450-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lynch DA, Dixon MF, Axon AT. Diagnostic criteria in lymphocytic gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1426-1427. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lynch DA, Sobala GM, Dixon MF, Gledhill A, Jackson P, Crabtree JE, Axon AT. Lymphocytic gastritis and associated small bowel disease: a diffuse lymphocytic gastroenteropathy. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:939-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Niemelä S, Karttunen T, Kerola T, Karttunen R. Ten year follow up study of lymphocytic gastritis: further evidence on Helicobacter pylori as a cause of lymphocytic gastritis and corpus gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1111-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dixon MF, Wyatt JI, Burke DA, Rathbone BJ. Lymphocytic gastritis--relationship to Campylobacter pylori infection. J Pathol. 1988;154:125-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hayat M, Arora DS, Dixon MF, Clark B, O'Mahony S. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the natural history of lymphocytic gastritis. Gut. 1999;45:495-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Müller H, Volkholz H, Stolte M. Healing of lymphocytic gastritis by eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Digestion. 2001;63:14-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Niemelä S, Karttunen TJ, Kerola T. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori in patients with lymphocytic gastritis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1176-1178. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Karttunen T, Niemelä S. Lymphocytic gastritis and coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43:436-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wolber R, Owen D, DelBuono L, Appelman H, Freeman H. Lymphocytic gastritis in patients with celiac sprue or spruelike intestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:310-315. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Griffiths AP, Wyatt J, Jack AS, Dixon MF. Lymphocytic gastritis, gastric adenocarcinoma, and primary gastric lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:1123-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Miettinen A, Karttunen TJ, Alavaikko M. Lymphocytic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric lymphoma. Gut. 1995;37:471-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brenes F, Ruiz B, Correa P, Hunter F, Rhamakrishnan T, Fontham E, Shi TY. Helicobacter pylori causes hyperproliferation of the gastric epithelium: pre- and post-eradication indices of proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1870-1875. [PubMed] |

| 15. | El-Zimaity HM, Graham DY, Genta RM, Lechago J. Sustained increase in gastric antral epithelial cell proliferation despite cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:930-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Augustin M, Karttunen TJ, Kokkonen J. TIA1 and mast cell tryptase in food allergy of children: increase of intraepithelial lymphocytes expressing TIA1 associates with allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Karttunen T, Niemelä S, Lehtola J. Helicobacter pylori in dyspeptic patients: quantitative association with severity of gastritis, intragastric pH, and serum gastrin concentration. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;186:124-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kuipers EJ, Lundell L, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Havu N, Festen HP, Liedman B, Lamers CB, Jansen JB, Dalenback J, Snel P. Atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis treated with omeprazole or fundoplication. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1018-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brittan M, Wright NA. Gastrointestinal stem cells. J Pathol. 2002;197:492-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Kato I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1302] [Cited by in RCA: 1234] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2805] [Cited by in RCA: 2739] [Article Influence: 80.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, Pan L, Moschini A, de Boni M, Isaacson PG. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1564] [Cited by in RCA: 1386] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sipponen P, Kekki M, Haapakoski J, Ihamäki T, Siurala M. Gastric cancer risk in chronic atrophic gastritis: statistical calculations of cross-sectional data. Int J Cancer. 1985;35:173-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |