Published online Nov 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2557

Revised: May 20, 2003

Accepted: June 4, 2003

Published online: November 15, 2003

AIM: To examine the regional variations in mortality rates of pancreatic cancer in China.

METHODS: Aggregated mortality data of pancreatic cancer were extracted from the 1990-1992 national death of all causes and its mortality survey in China. Age specific and standardized mortality rates were calculated at both national and provincial levels with selected characteristics including sex and residence status.

RESULTS: Mortality of pancreatic cancer ranked the ninth and accounted for 1.38% of the total malignancy deaths. The crude and age standardized mortality rates of pancreatic cancer in China in the period of 1990-1992 were 1.48/100000 and 1.30/100000, respectively. Substantial regional variations in mortality rates across China were observed with adjusted mortality rates ranging from 0.43/100000 to 3.70/100000 with an extremal value of 8.7. Urban residents had significant higher pancreatic mortality than rural residents.

CONCLUSION: The findings of this study show different mortality rates of this disease and highlight the importance of further investigation on factors, which might contribute to the observed epidemiological patterns.

- Citation: Chen KX, Wang PP, Zhang SW, Li LD, Lu FZ, Hao XS. Regional variations in mortality rates of pancreatic cancer in China: Results from 1990-1992 national mortality survey. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(11): 2557-2560

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i11/2557.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2557

Pancreatic cancer is a relatively common malignant disease in the world, both its incidence and mortality rate are ranked in the first ten cancers[1,2]. Especially in recent years, a gradually increased tendency of the disease has been found[3-6]. About 200000 new cases of pancreatic cancer are reported worldwide annually. Despite the overall improvement in cancer diagnosis and treatment in the past half century, there has been little change in the survival of pancreatic cancer patients. The reported worldwide annual incidence accounts for 2% of all malignant tumors and is associated with about 196000 deaths from the disease[7-11]. Though pancreatic cancer is relatively uncommon in China, but it still accounts for substantial cancer related deaths because of its dismal survival rate. Thus, the mortality rate of this disease serves as a mirror for its incidence. Notwithstanding previous studies in China have shown that there were significant geographic variations for several cancer sites, such as liver and esophagus, little is known for pancreatic cancer[12-14]. As the causes of pancreatic cancer are largely unknown, epidemiological studies on regional mortality rate variations may shed light on seeking possible modifiable factors associated with this disease.

1990-1992 national mortality survey As China does not have a centralized vital statistics system and cancer registration, national level information on disease specific mortality is often based on periodic national mortality surveys (NMS), the first of which was initiated in the early 1970s. Its purpose was to generate nationally representative estimates of mortality due to various health conditions, such as cancer, heart disease and stroke. The more recent one was conducted between 1990 and 1992 with the primary focus on malignant tumors, which was the data source for this study.

Briefly, the 1990-1992 NMS was a two-stage stratified probability survey. At the first stage, each of the 22 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, and 3 municipatities directly administrated cities under the Central Government (Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin) represented one of 30 strata. For the ease of the presentation, we referred to the 30 strata as "areas". The second stratum was formed at county or district level according to the cancer mortality levels (2-3 levels from low to high) from the previous survey. Thus, the primary sampling unit for this survey was county or district (for Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin). Overall, the sample size for this survey was designed to cover 10% of all deaths or 242 million baseline person years during the study period. Detailed information can be found from the National Mortality Survey Manual. With respect to pancreatic cancer, samples from 8 of the first level strata did not have sufficient number of cases to generate meaningful estimates, thus the mortality estimates were only applicable to 22 of the first level strata. Specifically, the 22 areas were Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Neimeng, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Anhui, Jiangxi, Fujian, Henan, Hunan, Hainan, Guangxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Gansu, and Ningxia.

Case assessment and baseline population All death certificates were retrieved from the local death registration offices for the sampled counties or districts. Local neighborhood representatives were also interviewed to further verify each deceased person for possible misreporting and discover deaths not reflected at death registration offices. Causes of deaths obtained from death certificates were checked with clinical records. When clinical records were missing or not available, possible diagnoses were solicited from the medical professionals who had once treated the case. Each reported cause of death was further converted into 3-digit ICD-9 codes and pancreatic cancer was determined for ICD-9157. Age-sex specific population data for each surveyed county or district were derived from interpolation using the data from the two most recent censuses conducted in 1982 and 1990.

Both crude and age-sex adjusted mortality rates were calculated both at provincial and national levels. In order to make the estimates comparable to reported mortality data from other populations, two standard populations were used: the 1980 Chinese population and the world standard population. The extremal quotient (EQ) was used to quantify regional variation[15]. The EQ is the ratio of the mortality from area with the highest level relative to the area with the lowest level. Age standardised mortality rates from each individual area (defined by resident status) were derived and compared with the corresponding national mean and median using the 1990-1992 NMS. In addition to assessing differences in mortality rate among areas and national levels, we also juxtaposed pancreatic cancer with other leading cancers, such as lung and breast cancers in terms of their relative ranking.

In total, pancreatic cancer deaths were identified from the 181 primary sampling units (counties or districts), among which 54 and 127 were considered as urban and rural respectively.

Table 1 displays the crude and standardized mortality rates of pancreatic cancer. As shown in this table, the crude and Chinese population adjusted mortality rates were 1.29 and 1.08 per 100000 person-year during the study period.

| Crude rate | ASMR1 | ASMR2 | Mortality proportion to all cancer death (%) | |

| Total | 1.48 | 1.30 | 1.74 | 1.38 |

| Male | 1.65 | 1.52 | 2.03 | 1.25 |

| Female | 1.29 | 1.08 | 1.46 | 1.62 |

Table 2 compares the mortality of pancreatic cancer with other leading cancers in terms of standardized rates, mortality proportion, and relative ranking. Overall, the mortality of pancreatic cancer ranked the 9th and accounted for 1.38% of total cancer deaths after colon cancer.

| Type of tumor | Males | Females | Total | ||||||

| ASR | P (%) | Rank | ASR | P (%) | Rank | ASR | P (%) | Rank | |

| Stomach | 30.78 | 25.10 | 1 | 14.52 | 21.80 | 1 | 22.51 | 23.93 | 1 |

| Liver | 25.73 | 21.42 | 2 | 9.55 | 14.00 | 3 | 17.75 | 18.74 | 2 |

| Esophagus | 20.22 | 16.45 | 4 | 10.32 | 15.50 | 2 | 15.15 | 16.11 | 4 |

| Lung | 21.68 | 17.73 | 3 | 9.03 | 13.46 | 4 | 15.23 | 16.18 | 3 |

| Rectum | 3.60 | 2.94 | 5 | 2.55 | 3.80 | 7 | 3.06 | 3.29 | 5 |

| Leukemia | 3.46 | 2.67 | 6 | 2.86 | 3.70 | 8 | 3.16 | 3.04 | 6 |

| Breast | 2.93 | 4.24 | 6 | ||||||

| Brain& nervous system | 2.01 | 1.63 | 7 | 1.48 | 2.02 | 9 | 1.74 | 1.77 | 7 |

| Cervix | - | - | - | 3.16 | 4.62 | 5 | - | - | |

| Colon | 1.49 | 1.21 | 9 | 1.19 | 1.80 | 10 | 1.34 | 1.43 | 8 |

| Pancreas | 1.52 | 1.25 | 8 | 1.08 | 1.62 | 11 | 1.30 | 1.38 | 9 |

| Total | 122.35 | 100.00 | 67.61 | 100.00 | 94.58 | 100.00 | |||

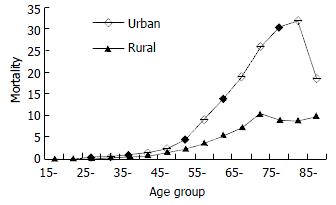

While pancreatic cancer could occur at any age, its mortality varied greatly among different age groups. The mortality remained low and did not increase until age 45, there was a steep increase in both males and females from age 45 to age 75 before it reached a plateau around 75. There seemed to be a mortality drop in males after age 75. Pancreatic cancer mortality rates were apparently higher in males than in females, with the ratio 1.4:1.

Regional comparisons (Table 3) suggested that a substantial variation in pancreatic cancer mortality across the 22 regions and standardized mortality rates varied from the lowest 0.47/100000 person-year in Hunan Province to the highest 3.73/100000 person year in Shanghai with an extremal quotient of 8.76. Using the national average level as a standard, eight provinces had a rate higher than average and they were Shanghai, Tianjin, Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Jiangsu, Jilin, Beijing, and Ningxia. However, there was little variation in terms of mortality, sex ratios varying between 1.07 and 2.3, most of the values were around 1.5.

| Regions | Males | Females | Total | M/F ratio | |||

| CR | ASR | CR | ASR | CR | ASR | ||

| Hunan | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 1.69 |

| Guangxi | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 2.03 |

| Hainan | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 1.58 |

| Gansu | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 1.78 |

| Guizhou | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 1.94 |

| Jiangxi | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 1.48 |

| Henan | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 1.63 |

| Sichuan | 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.92 | 0.79 | 1.57 |

| Fujian | 1.32 | 1.36 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 2.27 |

| Neimenggu | 1.72 | 1.16 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 1.31 | 0.99 | 1.43 |

| Shanxi | 1.34 | 1.21 | 1.02 | 0.89 | 1.19 | 1.04 | 1.36 |

| Yunnan | 1.38 | 1.24 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 1.19 | 1.05 | 1.43 |

| Hebei | 1.49 | 1.37 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 1.23 | 1.08 | 1.69 |

| Anhui | 1.50 | 1.44 | 1.20 | 0.96 | 1.36 | 1.20 | 1.50 |

| Ningxia | 1.85 | 1.68 | 1.17 | 1.06 | 1.52 | 1.38 | 1.58 |

| Beijing | 3.21 | 2.28 | 1.97 | 1.25 | 2.59 | 1.75 | 1.82 |

| Jilin | 2.07 | 1.98 | 1.80 | 1.85 | 1.94 | 1.91 | 1.07 |

| Jiangsu | 3.29 | 2.62 | 3.29 | 2.20 | 3.29 | 2.40 | 1.19 |

| Heilongjiang | 2.52 | 2.57 | 2.26 | 2.38 | 2.40 | 2.47 | 1.08 |

| Liaoning | 3.71 | 3.16 | 2.76 | 2.38 | 3.24 | 2.78 | 1.33 |

| Tianjin | 5.68 | 3.80 | 4.53 | 2.91 | 5.10 | 3.34 | 1.31 |

| Shanghai | 7.55 | 4.22 | 6.87 | 3.26 | 7.21 | 3.70 | 1.29 |

These comparisons further indicated that urban residents had a significant higher mortality than their rural counterparts. These differences existed in both males and females (Table 4, Figure 1) across age groups.

| Region | Sex | CR | ASR |

| Total | Urban | 2.83 | 2.27 |

| Rural | 1.05 | 0.95 | |

| U/R ratio | 2.67 | 2.39 | |

| Male | Urban | 3.16 | 2.68 |

| Rural | 1.17 | 1.11 | |

| U/R ratio | 2.70 | 2.41 | |

| Female | Urban | 2.47 | 21.89 |

| Rural | 0.92 | 0.80 | |

| U/R ratio | 2.68 | 2.36 |

In this study, we described some epidemiological characteristics of pancreatic cancer using the most recent Chinese mortality survey data. Compared with other previous studies in China, the age standardized mortality rates from this study appeared to be higher than those reported previously. This may suggest that the mortality rate of pancreatic cancer is increasing.

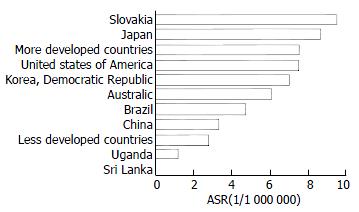

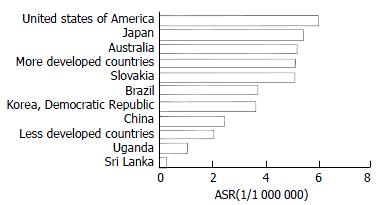

Ecological studies[16-24] found as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, that the mortality of pancreatic cancer seemed to be correlated with the level of economic development. Developed countries, such as Japan and the United States[25-29] had a higher pancreatic cancer mortality than that of less developed countries, such as some African countries[30-33]. China is a big country with unbalanced economic development and diverse lifestyles. The economic developmental gaps between urban and rural areas seen in China are greater than those in the developed countries. Findings from this study suggest substantial regional variations in the mortality rates of pancreatic cancer and in general, economically more developed regions have higher mortality rates than that of less developed regions. For example, Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin shared the 3 highest mortality rates. Thus, results from this study are in accord with previous observations.

The use of a population based national representative sample in the present study was unique in its reliability. Also, in this study most death certificates were crossly validated and consequently the reported causes of death were more believable. Furthermore, as all studied areas used uniform standards, the mortality rate estimates across areas had a good comparability. However, there were also limitations associated with this study. First, all information used in this study was derived from the survey, thus the case assessment method could not be compared with clinical diagnosis. Second, since this survey did not collect life style information (such as smoking and diet) for the deceased subjects, we were restricted from further exploring the impact of potential risk factors on this condition. Lastly, only aggregated data were available to the authors, we were unable to calculate the variances for the estimated mortality rates. As a result, we could only provide point estimates without 95% confidence intervals.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a substantial variation in pancreatic cancer mortality rates across the Mainland China. The results reported in this study beg for answers to the observed differences. As pancreatic cancer is a fast growing disease associated with high fatality, more in-depth epidemiological studies on identifying modifiable risk factors are warranted.

We are grateful to all medical workers from 22 provinces (cities, districts) in China for our data collection and preparation. We want to thank Tianjin Cancer Institute and Hospital for its financial support.

Edited by Xu JY and Wang XL

| 1. | Levi F, Lucchini F, Negri E, Boyle P, La Vecchia C. Mortality from major cancer sites in the European Union, 1955-1998. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:490-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Remontet L, Estève J, Bouvier AM, Grosclaude P, Launoy G, Menegoz F, Exbrayat C, Tretare B, Carli PM, Guizard AV. Cancer incidence and mortality in France over the period 1978-2000. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2003;51:3-30. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Fernandez E, La Vecchia C, Porta M, Negri E, Lucchini F, Levi F. Trends in pancreatic cancer mortality in Europe, 1955-1989. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:786-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vutuc C, Waldhoer T, Haidinger G. Impact of non-invasive imaging techniques on the trend of pancreatic cancer mortality in Austria. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1996;146:258-260. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lin RS, Lee WC. Mortality trends of pancreatic cancer: An affluent type of cancer in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 1992;91:1148-1153. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yang CY, Chiu HF, Cheng MF, Tsai SS, Hung CF, Tseng YT. Pancreatic cancer mortality and total hardness levels in Taiwan's drinking water. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1999;56:361-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bakkevold KE, Kambestad B. Morbidity and mortality after radical and palliative pancreatic cancer surgery. Risk factors influencing the short-term results. Ann Surg. 1993;217:356-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Riggs JE. Longitudinal Gompertzian analysis of pancreatic cancer mortality in the U.S., 1962-1987: distinguishing between competitive and environmental influences upon evolving mortality patterns. Mech Ageing Dev. 1991;61:197-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Binstock M, Krakow D, Stamler J, Reiff J, Persky V, Liu K, Moss D. Coffee and pancreatic cancer: An analysis of international mortality data. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118:630-640. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Calle EE, Murphy TK, Rodriguez C, Thun MJ, Heath CW. Diabetes mellitus and pancreatic cancer mortality in a prospective cohort of United States adults. Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9:403-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pickle LW, Gottlieb MS. Pancreatic cancer mortality in Louisiana. Am J Public Health. 1980;70:256-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Boffetta P, Burstyn I, Partanen T, Kromhout H, Svane O, Langård S, Järvholm B, Frentzel-Beyme R, Kauppinen T, Stücker I. Cancer mortality among European asphalt workers: An international epidemiological study. II. Exposure to bitumen fume and other agents. Am J Ind Med. 2003;43:28-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gapstur SM, Gann PH, Lowe W, Liu K, Colangelo L, Dyer A. Abnormal glucose metabolism and pancreatic cancer mortality. JAMA. 2000;283:2552-2558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ghadirian P, Thouez JP, PetitClerc C. International comparisons of nutrition and mortality from pancreatic cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 1991;15:357-362. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Neoptolemos JP, Russell RC, Bramhall S, Theis B. Low mortality following resection for pancreatic and periampullary tumours in 1026 patients: UK survey of specialist pancreatic units. UK Pancreatic Cancer Group. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1370-1376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ghadirian P, Lynch HT, Krewski D. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: An overview. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Patel AV, Thun MJ. Predictors of pancreatic cancer mortality among a large cohort of United States adults. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:915-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Imaizumi Y. Longitudinal Gompertzian analysis of mortality from pancreatic cancer in Japan, 1955-1993. Mech Ageing Dev. 1996;90:163-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bardin JA, Eisen EA, Tolbert PE, Hallock MF, Hammond SK, Woskie SR, Smith TJ, Monson RR. Mortality studies of machining fluid exposure in the automobile industry. V: A case-control study of pancreatic cancer. Am J Ind Med. 1997;32:240-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Clary T, Ritz B. Pancreatic cancer mortality and organochlorine pesticide exposure in California, 1989-1996. Am J Ind Med. 2003;43:306-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Inoue M, Tajima K, Takezaki T, Hamajima N, Hirose K, Ito H, Tominaga S. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer in Japan: A nested case-control study from the Hospital-based Epidemiologic Research Program at Aichi Cancer Center (HERPACC). Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kauppinen T, Heikkilä P, Partanen T, Virtanen SV, Pukkala E, Ylöstalo P, Burstyn I, Ferro G, Boffetta P. Mortality and cancer incidence of workers in Finnish road paving companies. Am J Ind Med. 2003;43:49-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mohan AK, Hauptmann M, Freedman DM, Ron E, Matanoski GM, Lubin JH, Alexander BH, Boice JD, Doody MM, Linet MS. Cancer and other causes of mortality among radiologic technologists in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:259-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Konner J, O'Reilly E. Pancreatic cancer: epidemiology, genetics, and approaches to screening. Oncology (. Williston Park). 2002;16:1615-122, 1615-122, discussion 1615-1622, 1615-1622. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Lee WC, Lin RS. Age-period-cohort analysis of pancreatic cancer mortality in Taiwan, 1971-1986. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:839-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mulder I, Hoogenveen RT, van Genugten ML, Lankisch PG, Lowenfels AB, de Hollander AE, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB. Smoking cessation would substantially reduce the future incidence of pancreatic cancer in the European Union. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1343-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Newnham A, Quinn MJ, Babb P, Kang JY, Majeed A. Trends in oesophageal and gastric cancer incidence, mortality and survival in England and Wales 1971-1998/1999. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:655-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lee IM, Sesso HD, Oguma Y, Paffenbarger RS. Physical activity, body weight, and pancreatic cancer mortality. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:679-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zervos EE, Norman JG, Gower WR, Franz MG, Rosemurgy AS. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition attenuates human pancreatic cancer growth in vitro and decreases mortality and tumorigenesis in vivo. J Surg Res. 1997;69:367-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Muirhead CR, Bingham D, Haylock RG, O'Hagan JA, Goodill AA, Berridge GL, English MA, Hunter N, Kendall GM. Follow up of mortality and incidence of cancer 1952-98 in men from the UK who participated in the UK's atmospheric nuclear weapon tests and experimental programmes. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Corella Piquer D, Cortina Greus P, Coltell Simón O. [Nutritional factors and geographic differences in pancreatic cancer mortality in Spain]. Rev Sanid Hig Publica (. Madr). 1994;68:361-376. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Olsen GW, Lacy SE, Bodner KM, Chau M, Arceneaux TG, Cartmill JB, Ramlow JM, Boswell JM. Mortality from pancreatic and lymphopoietic cancer among workers in ethylene and propylene chlorohydrin production. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:592-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pasquali C, Sperti C, Filipponi C, Pedrazzoli S. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer in Northeastern Italy: incidence, resectability rate, hospital stay, costs and survival (1990-1992). Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:723-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |