Published online Aug 15, 2002. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i4.703

Revised: July 7, 2002

Accepted: July 11, 2002

Published online: August 15, 2002

AIM: The widespread use of antibacterial therapy has been suggested to be the cause for the decline in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. This study examine the serial changes of urea breath test results in a group of hospitalized patients who were given antibacterial therapy for non-gastric infections.

METHODS: Thirty-five hospitalized patients who were given antibacterial therapy for clinical infections, predominantly chest and urinary infections, were studied. Most (91%) patients were given single antibiotic of either a penicillin or cephalosporin group. Serial 13C-urea breath tests were performed within 24 h of initiation of antibiotics, at one-week and at six-week post-therapy. H. pylori infection was diagnosed when one or more urea breath tests was positive.

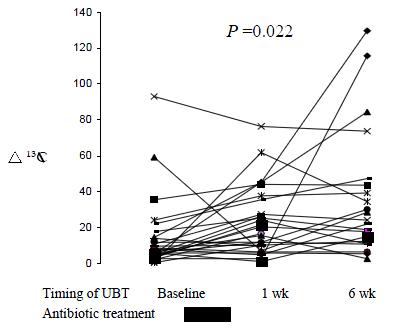

RESULTS: All 35 patients completed three serial urea breath tests and 26 (74%) were H. pylori-positive. Ten (38%) H. pylori-infected patients had at least one negative breath test results during the study period. The medium delta 13C values were significantly lower at baseline (8.8) than at one-week (20.3) and six-week (24.5) post-treatment in H. pylori-positive individuals (P = 0.022). Clearance of H. pylori at six-week was only seen in one patient who had received anti-helicobacter therapy from another source.

CONCLUSION: Our results suggested that one-third of H. pylori-infected individuals had transient false-negative urea breath test results during treatment with antibacterial agent. However, clearance of H. pylori infection by regular antibiotic consumption is rare.

- Citation: Leung WK, Hung LCT, Kwok CKL, Leong RWL, Ng DKK, Sung JJY. Follow up of serial urea breath test results in patients after consumption of antibiotics for non-gastric infections. World J Gastroenterol 2002; 8(4): 703-706

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v8/i4/703.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v8.i4.703

The rediscovery of Helicobacter pylori in 1984 had revolutionized our understanding of gastroduodenal diseases[1]. This bacterium is now generally considered to be the most important cause of peptic ulcer diseases, gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma of the stomach[2,3]. Unless given appropriate antibiotic treatment, most infected individuals will remain infected throughout their lifetime. Spontaneous clearance of infection, particularly in adult, is rare[4,5].

Interestingly, recent epidemiological studies suggest a gradual reduction in the prevalence of H. pylori infection, particularly in developed countries[4]. This decline in H. pylori prevalence is accompanied by a parallel reduction in the incidence of gastric carcinoma[6]. The reason for this decrease remains unknown for the moment but widespread use of antibiotics in the community has been speculated to be an important cause for this decline. This study sought to determine the serial changes of urea breath test in patients after taking antibacterial agents given for conditions other than H. pylori infection. The aim is to elucidate the effects of antibacterial agents on urea breath test results and determine whether antibacterial therapy given for concomitant infections would result in clearance of H. pylori infection.

Patients who were hospitalized for clinical infections, other than gastrointestinal tract infection, and requiring the use of antibiotics were recruited. The prescription of antibacterial agent was at the discretion of the attending clinicians. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, had previous gastric surgery, had previously received anti-helicobacter treatment, or had been using acid-suppressive agents or antibiotics in the recent six weeks. For all eligible patients, informed consent was obtained from the patients or their parents. Since it is unethical to delay or withhold anti-bacterial therapy, urea breath test was performed as soon as possible but usually performed after the initiation of the antibacterial agents. All urea breath tests, however, should be performed within 24 h of admission. Subsequent urea breath tests were repeated at one-week and at six-week after the completion of antibiotics. Drug history during the study period, including acid suppressive therapies and antibiotics, was recorded. All patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection were offered H. pylori eradication therapy at the conclusion of this study. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Kwong Wah Hospital of Hong Kong SAR.

13C urea breath test

13C-urea breath test (UBT) was performed in all patients, adult or children, following the same protocol. All patients were fasted for a minimum of four hours and were then given a citric acid test meal to delay gastric emptying. A 75-mg 13C-urea tablet dissolved in water was then given. Breath samples were collected before the test meal and 30 min after the ingestion of the urea solution. Two devices, a 10-mL glass tube and a sealed aluminum bag, were used for collection of exhaled air. The difference in 13CO2 between the two breath samples was analyzed by both the isotope ratio mass spectrometry (Europa Scientific, Crewe, UK) and the infrared spectrometer (FANci2, Fischer Analysen Instrumente, Leipzig, Germany). A concordant delta 13CO2 value greater than 5 was regarded as a positive result as described previously[7].

Since none of these patients had indication for endoscopy, H. pylori infection status was determined by the non-invasive urea breath test. Patients were classified as H. pylori-positive when one or more of the three consecutive breath test results tested positive. This was based on the assumptions that urea breath test was accurate in diagnosing H. pylori infection, and that natural acquisition of H. pylori infections was extremely rare[4,5]. Serology test (ASSURE; Genelabs Diagnostics, Singapore) was used in patients with three consecutive negative urea breath tests for the detection of IgG anti-Helicobacter antibody to rule out the possibility of false negative breath test results. This serology test has been previously validated in our population[8].

All statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism version 2.01 (San Diego, CA, USA). Comparisons of the delta 13C values among the three consecutive urea breath tests were made by Kruskal-Wallis test. Post-hoc analysis was performed by Dunn's multiple comparison test.

A total of 35 patients were examined in this study (median age = 66 years, range 5-81; 13 male and 22 female). Two study subjects were less than 18 years of age. The primary diagnoses of these patients were chest infection (n = 20), urinary tract infection (n = 12) and other infections (n = 3). Thirty-two (91%) patients received a single antibiotic whereas three (9%) received two antibacterial agents during the hospitalization period. All patients received a one- to two-week course of standard dose penicillin (n = 20) or cephalosporin (n = 15) during the study period. Intravenous route was initially given in 25 (71%) patients whereas the rest received oral antibiotics throughout the hospitalizations. One patient also received a course of anti-Helicobacter therapy from his primary care physicians during the follow up period.

All 35 patients completed the three consecutive urea breath tests. By using the pre-defined criterion, 26 (74%) patients were considered to be H. pylori-positive. None of the remaining 9 patients with negative breath tests had anti-Helicobacter antibody detected.

The serial breath test results of the study patients were given in Table 1. Ten (29%) H. pylori-positive patients had at least one negative urea breath test results during the study period. Of these 10 patients, 7 had the first test result negative whereas the second and/or third test was (were) positive. Two patients had a single negative test result at one-week post-treatment. Among the 26 H. pylori-positive patients, only one was found to have a negative test result at six-week post-antibiotic treatment. However, this patient had been prescribed a one-week course of proton-pump inhibitor-based triple therapy for dyspepsia by his primary care practitioner two weeks after discharge from hospital. It thus appeared that the apparent clearance of H. pylori was attributed to the specific anti-Helicobacter therapy instead of the first course of antimicrobial agent.

| Baseline | UBT | No. of patients | |

| 1-wk post-antibacterial therapy | 6-wk post-antibacterial therapy | ||

| Neg | Neg | Neg | 9 |

| Neg | Neg | Pos | 1 |

| Neg | Pos | Pos | 6 |

| Pos | Neg | Pos | 2 |

| Pos | Pos | Neg | 1* |

| Pos | Pos | Pos | 16 |

| Total | 35 | ||

For all H. pylori infected patients, the median delta 13CO2 values taken at baseline, one-week and six-week post-treatment were 8.8, 20.3 and 24.5 respectively (P = 0.022). Post-hoc analysis showed that the median value measured at baseline was significantly lower than at six-week post treatment (P < 0.05). On the other hand, the difference between the first and second urea breath tests did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1).

All patients who had a transient negative urea breath test result were given antibiotics by the intravenous route whereas 10 (56%) of the H. pylori-infected patients with persistent positive breath test results received intravenous antibiotics (P = 0.05). On the other hand, the choice and duration of antibiotic therapy did not correlate with false negative breath test results.

Urea breath test is considered to be the best non-invasive test for diagnosis of H. pylori infection, which is useful in both diagnosis and post-treatment testing. However, it can be potentially influenced by drugs that cause suppression of H. pylori and hence, its urease activity. In this regard, the proton pump inhibitor is the drug that is most extensively examined. Laine et al[9] showed that 33% of H. pylori-infected patients had a negative breath test result when receiving standard dose of lansoprazole for the treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease. The breath test results returned positive in all patients at 14-day after stopping the treatment. Although antibiotic combinations are used in the treatment of H. pylori, the effect of concomitant antibacterial agents given for other conditions, usually single drug, on urea breath test results has not been evaluated.

In this study, we prospectively studied the serial changes of urea breath tests in a small group of hospitalized patients who were given antibiotics for infections other than H. pylori. Despite the small number of patients examined, the results of this study could provide insights into the effects of antibacterial therapy on urea breath test results and hence H. pylori statuses post-treatment. Unlike proton pump inhibitor with limited choices and relatively well-defined standard doses, the choices of antibiotics and the duration of therapy are highly variable. Most of our study subjects suffered from chest or urinary tract infections and were given a 1-2 week course of penicillin or cephalosporin. As shown by our results, antibacterial agents frequently (38%) caused false-negative breath test results in H. pylori-infected individuals. This was best illustrated by the significantly lower delta 13CO2 value of first test results while receiving antibacterial treatment. This transient suppression occurred within 24 h of antibiotics treatment and could last for more than one-week post-treatment. Nevertheless, none of the study subjects, except the one who had received specific anti-Helicobacter treatment, had a persistent negative breath test at 6-week.

This observation is important for three reasons. First, the widespread use of antibiotics in the community for various infections have been speculated to be a major reason for the decline in prevalence of H. pylori infection and possibly the decline in gastric cancer incidences worldwide. This is supported by a recent epidemiological study that demonstrated a reduced risk of gastric cancer among patients who were given antibiotic prophylaxis for hip replacement surgery[10]. Their protective effect is presumably due to the serendipitous eradication of H. pylori by the antibiotics, which leads to subsequent reduction in the risk of development of gastric cancer. However, if one looks into the rate of disappearance of anti-Helicobacter antibody in patients who were given antibiotics, it was not significantly higher than control suggesting that the reduction in cancer incidences may not be directly related to the clearance of H. pylori, at least from serological point of view. In the present study, clearance of H. pylori after a single course of antibiotic is rare. Despite the in vitro sensitivity of H. pylori, the eradication rate of a single standard dose of antibacterial agent is extremely low, particularly with the use of penicillin and cephalosporin groups. Previous data showed that the best single therapy for H. pylori is clarithromycin[11]. Nonetheless, the use of two-week high dose clarithromycin (2 gram per day) could only achieve eradication of H. pylori in about one-third of the patients[11]. In practice, the success of eradication is low without acid suppressive agent such as proton pump inhibitors or bismuth compounds[12]. The second importance of this study is the potential risk of inducing acquired resistance with repeated exposure to antimicrobial agent. Exposure of H. pylori to antimicrobial agents without eliminating the bacteria poses a major risk of inducing acquired resistance. This may offer a plausible explanation for the rising incidence of antibiotic resistance in countries where there is high consumption of antibiotics[13-15]. The third reason for the importance of this paper would be that treatment of antibiotics affect diagnostic accuracy of UBT.

The prevalence of H. pylori infection in this study (74%) is much higher than previously reported in local dyspeptic patients. This is most likely due to random effect in study involving small number of patients. Ideally, baseline urea breath test should be performed prior to the administration of antibiotics and biopsy-based diagnosis should be used for the proper documentation of H. pylori status, but for ethnical reasons, these problems are difficult to overcome. However, we have performed serology tests in patients who had negative urea breath tests to detect presence of anti-helicobacter antibody. Thus, the chance of misclassifying H. pylori-positive patient as negative would be minimal.

In conclusion, this study showed that over one-third of patients had a transient suppression of urease activity and hence, false-negative urea breath test results during treatment with antibacterial agents. This usually reverts back to normal at six-week post treatment and thus, testing for H. pylori should be postponed accordingly. On the other hand, spontaneous clearance of H. pylori by antibacterial agent given for other conditions is extremely rare, and could not account for the fall in prevalence of H. pylori in most developed countries.

Edited by Zhang JZ

| 1. | Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311-1315. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Marshall BJ; Anonymous. NIH Consensus Conference. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. JAMA. 1994;272:65-69. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Marshall BJ; Anonymous. Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:8-13. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Xia HH, Talley NJ. Natural acquisition and spontaneous elimination of Helicobacter pylori infection: clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1780-1787. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kumagai T, Malaty HM, Graham DY, Hosogaya S, Misawa K, Furihata K, Ota H, Sei C, Tanaka E, Akamatsu T. Acquisition versus loss of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: results from an 8-year birth cohort study. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:717-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pisani P, Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide mortality from 25 cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:18-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Leung WK, Chan FK, Falk MS, Suen R, Sung JJ. Comparison of two rapid whole-blood tests for Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3441-3442. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Hung CT, Leung WK, Chan FK, Sung JJ. Comparison of two new rapid serology tests for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Laine L, Estrada R, Trujillo M, Knigge K, Fennerty MB. Effect of proton-pump inhibitor therapy on diagnostic testing for Helicobacter pylori. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:547-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Akre K, Signorello LB, Engstrand L, Bergström R, Larsson S, Eriksson BI, Nyrén O. Risk for gastric cancer after antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing hip replacement. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6376-6380. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Leung WK, Graham DY. Clarithromycin for Helicobacter pylori infection. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2000;1:507-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lind T, Mégraud F, Unge P, Bayerdörffer E, O'morain C, Spiller R, Veldhuyzen Van Zanten S, Bardhan KD, Hellblom M, Wrangstadh M. The MACH2 study: role of omeprazole in eradication of Helicobacter pylori with 1-week triple therapies. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:248-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mégraud F. Epidemiology and mechanism of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1278-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Osato MS, Reddy R, Reddy SG, Penland RL, Malaty HM, Graham DY. Pattern of primary resistance of Helicobacter pylori to metronidazole or clarithromycin in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1217-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim JJ, Reddy R, Lee M, Kim JG, El-Zaatari FA, Osato MS, Graham DY, Kwon DH. Analysis of metronidazole, clarithromycin and tetracycline resistance of Helicobacter pylori isolates from Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:459-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |