INTRODUCTION

Duodenogastric reflux (DGR) is a natural physiologic phenomenon often occurring during the early hours of the morning and postprandial period[1]. When excessive, it may be pathological. Accurate detection of DGR has been a major problem for many years. Most methods used to detect DGR were of short periods, indirect and not in a physiological condition and with other shortcomings[2,3]. Ambulatory intragastric pH monitoring allows a physiological method of measuring rises in intragastric pH with an extended sampling period, but it cann't reliably distinguish between DGR and other causes of increased pH levels and it is an indirect technique. At present an ambulatory fiberoptic spectrophotometer that detects the presence of bilirubin (Bilitec 2000) is universally recognized as a reliable method[4-11]. This has made it feasible to qualitatively detect DGR for prolonged sampling periods in physiological setting. Up to date, there has been no report about the diagnostic value of a combined continuous intragastric pH and bilirubin monitoring in the assessment of DGR in China. We used Bilitec 2000 along with simultaneous ambulatory intragastric pH monitoring to evaluate its diagnostic value in DGR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Thirty healthy control subjects, 16 male, 14 female, mean age 45 ± 11, (range 20-70) years, were enrolled in this study. They were randomly divided into two groups: group 1 (standard diet group), 8 male, 10 female, mean age 45 ± 11 years and group 2 (free diet group), 7 male, 5 female, mean age 46 ± 10 years.

Methods

pH measurements were performed with an antimony electrode and bile measurement with a fiberoptic probe. Both catheter were connected to separate portable digital data recorders (Digitrapper Mark III and Bilitec 2000 recorder, Synectics). The pH electrodes were calibrated in buffer solution of pH1 and pH7 before and after the measurement. The calibration of the Bilitec 2000 was done in a small nontransparent tube before each test. The tip of pH catheter was tied with silk thread to the fiberoptic Bilitec probe, in a way the tip of the pH catheter slightly above the gap of the Bilitec probe, so that both measurements were registered almost at the same position.

Both probes were then passed transnasally after 12-h fasting and positioned in the gastric corpus 5 cm below the lower border of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES)[3,12]. The localization of the LES was determined by esophageal perfusion manometry. After 24 h the probes were removed, and the data were downloaded to a PC for analysis with Esophogram software. 24-hour gastric pH record was divided in four periods: the upright period, the supine period, the prandial pH plauteau period and the postprandial pH decline period[13]. The preprandial period pH and the postprandial period (include the prandial pH plauteau period and the postprandial pH decline period) pH were compared in this study. The absorbance ≥ 0.14 was used as Bilitec threshold values.

Group 1 were asked to take allowed food with bilirubin absorbance never exceeding 0.14 (rage 0.02-0.11) in vitro, such as milk, bread, rice, noodles, fish soup, chicken soup, boiled potatoes, lotus roots, pears and so on, the total calorie of three meals being about 8.4 × 106 J. The foods were detected in another unpublicized study. Group 2 were allowed to take free food except coffee and orange juice. The foods should be finely minced to avoid solid food pollution of the tip of the probe. All subjects were advised to eat three times a day and not to drink between meals. Smoking and alcohol were not allowed.

Statistcal analysis

All results were expressed as ¯x ± s. Data were analyzed by Student's t test and linear regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Intragastric pH of preprandial and postprandial period in two groups

Intragastric pH was significantly higher in postprandial period in two groups. In Group 1 and in group 2, intragastric pH of postprandial period compared with preprandial period were 3.6 ± 1.1 vs 2.0 ± 0.6, P < 0.05, and 3.8 ± 1.2 vs 2.1 ± 0.8, P < 0.05, respectively.

Intragastric bilirubin absorbance of preprandial and postprandial period in two groups

There was no difference of preprandial phase absorbance between two groups. The absorbance of postprandial phase was significantly increased in group 2 than group 1, 0.20 ± 0.04 vs 0.10 ± 0.08, P < 0.05.There was no difference between preprandial phase and postprandial phase absorbance in group 1. Postprandial phase absorbance was significantly higher in group 2, 0.20 ± 0.04 vs 0.10 ± 0.03, P < 0.05.

Intragastric pH and bile reflux changes in overnight fasting

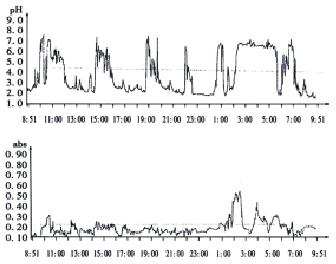

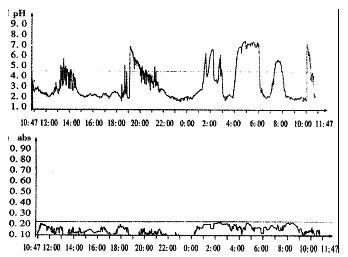

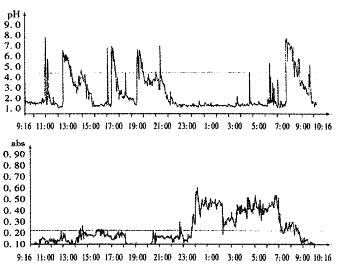

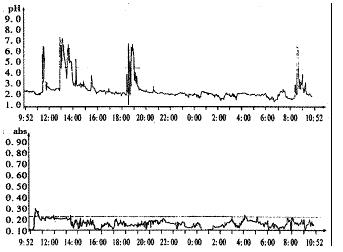

In a comparison of bile reflux with pH monitoring during night time in group 1, there were 4 types of reflux: Simultaneous increase in absorbance and pH in only 19.6%, increase in bilirubin with unchanged pH 33.3% or pH increase with unchanged absorbance 36.3%, increase in either one of the two parameters 69.6%, and both unchanged 10.8%. Moreover, Linear regression analysis showed no correlation between percentage total time of pH > 4 and percentage total time of absorbance > 0.14, r = 0.068, P < 0.05 (Figure 1 Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4).

Figure 1 Simultaneous increase of intragastric pH and bilirubin absorbance

Figure 2 Intragastric pH increase with constant bilirubin absorbance

Figure 3 Bilirubin absorbance increase with constant intragastric pH

Figure 4 Intragastric pH and bilirubin absorbance both constant

DISCUSSION

Based on the experience in the esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease, Litter et al[14] first applied intragastric 24 h monitoring for evaluation of the alkaline reflux. Since then 24 h intragastric pH monitoring has been used in many studies of DGR[15-20]. It is an indirect technique and is not capable of such detection in hypochlorhydric stomachs and in the prandial period. So there exist limitations in the diagnosis of DGR[21,22]. Bilitec 2000 is a new fiberoptic spectrophotometer that relies on the optical properties of bile to detect duodenogastric bile reflux (DGBR) in ambulatory setting independent of pH[23]. Bilirubin is the most common pigment in bile, with a characteristic absorption peak of 470 nm[24]. The basic working principle of the Bilitec 2000 is that an absorption at 470 nm automatically implies the presence of bilirubin, and therefore, bile in the sample under consideration. In the presence of bile alone, the degree of absorbance is proportional to the bilirubin concentration[25]. Bilitec may be an important advancement in the field of detecting DGR, permitting more accurate studies of patients with syndromes associated with DGR.

With Bilitec 2000 a threshold value is 0.14 absorbance[3,23,26], beyond which bile reflux is considered to be present. This threshold value takes into account scattering effects due to the gastric content such as suspended particles and mucus, which can give rise to a Bilitec readout ranging from 0 to 0.13 absorbance units, which, however, is not to be ascribed to bilirubin absorbance[23].

In this study the results showed that the intragastric pH in the postprandial period was higher than that in preprandial in both groups because of neutralization by food. In group 1 the bilirubin absorbance was lower than 0.14 in both period. In group 2 postprandial absorbance of (0.20 ± 0.04) was significantly increased than preprandial (0.10 ± 0.03). So measurement could be affected by the diet[27]. Some foods with an absorbance at between 400-450 nm are capable of resulting in false positive results. In order to accurately access DGBR, the foods with high absorbance should be avoided (e.g. coffee, coke, carrot, tomato, etc.). Fein et al[28] reported if a threshold of absorbance of 0.25 was used, a free diet except coffee could be allowed for measurements.

In our study Bilitec 2000 along with simultaneous ambulatory intragastric pH monitoring showed a poor correlation between intragastric pH and DGBR. These results was consistent with other reports[29,30]. How to explain the discrepancy Duodenal juice consists of intestinal secretion, pancreatic secretion and bile. A previous study[1] using gastric aspiration and antroduodenal manometry showed a relationship among secretory activity, migrating motor complex (MMC) and DGR. DGR was highest during the late phase II of MMC and lowest after phase III. The duodenal bicarbonate output was highest after the onset of phase III while bile acid output was highest prior to the onset of phase III. Perhaps the reason for the poor correlation between intragastric pH and DGBR was related to variations of the amount of and different components in the regurgitated duodenal juice. If duodenogastric reflux fluid contains more bile and sufficient bicarbonate contents, both intragastric pH and absorbance are increased. If the reflux fluid consists mainly of duodenal bicarbonate and/or pancreatic secretion with less bile contents, rise of intragastric pH is observed owing to the buffering capacity of the fluid, and the absorbance remains unchanged. Conversely, if bile reflux occurs with less duodenal bicarbonate and pancreatic secretion, or in the absence of duodenoal bicarbonate and pancreatic secretion, absorbance is increased with unchaged pH, because the low bicarbonate buffering capacity can not change the pH. Fushs et al[31] studied the variability in the composition of physiologic duodenogastric reflux and found pancreatic enzyme aspirate was significantly more often associated with a rise in pH in comparison to bile reflux (P < 0.01).

In conclusion, because of the dietary effect, high absorbance fluids or foods should be avoided in the detection. Intragastric pH and bilirubin monitoring separately predict the presence of duodenal (and/or pancreatic) reflux and bile reflux. They can not substitute for each other. The detection of DGR is improved if the two parameters are combined simultaneously.