Published online Jun 15, 2001. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i3.324

Revised: April 19, 2001

Accepted: April 26, 2001

Published online: June 15, 2001

AIM: To determine whether normal genetically immunocompetent rodent hosts could be manipulated to accept human hepatocyte transplants with long term survival without immunosuppression.

METHODS: Tolerance towards human hepatocytes was established by injection of primary human hepatocytes or Huh7 human hepatoma cells into the peritoneal cavities of fetal rats. Corresponding cells were subsequently transplanted into newborn rats via intrasplenic injection within 24 h after birth.

RESULTS: Mixed lymphocyte assays showed that spleen cells from non-tolerized rats were stimulated to proliferate when exposed to human hepatocytes, while cells from tolerized rats were not. Injections made between 15 d and 17 d of gestation produced optimal tolerizaton. Transplanted human hepatocytes in rat livers were visualized by immunohistochemical staining of human albumin. By dot blotting of genomic DNA in livers of tolerized rats 16 weeks after hepatocyte transplantation, it was found that approximately 2.5 × 105 human hepatocytes survived per rat liver. Human albumin mRNA was detected in rat livers by RT-PCR for 15 wk, and human albumin protein was also detectable in rat serum.

CONCLUSION: Tolerization of an immunocompetent rat can permit transplantation, and survival of functional human hepatocytes.

- Citation: Ouyang EC, Wu CH, Walton C, Promrat K, Wu GY. Transplantation of human hepatocytes into tolerized genetically immunocompetent rats. World J Gastroenterol 2001; 7(3): 324-330

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v7/i3/324.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v7.i3.324

Transplantation of allogeneic hepatocytes into immunocompetent rodents has been shown to result in rejection of donor cells by host immune system, with T-cell activation, and a delayed type hypersensitivity reaction[1-3]. This can been overcome by generalized immunosuppression or through the use of genetically immunodeficient animals[4-8]. Another strategy to avoid rejection is by inducing immunological tolerance specifically to the transplanted cells. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that the ability of the immune system to distinguish between endogenous and exogenous antigens develops shortly before birth. Studies have shown that if foreign antigens are introduced during this formative period, when the animals mature, they will be tolerant to those antigens[9], permitting the survival of allogeneic (cardiac) transplants in rats[10,11]. We hypothesized that, if human liver cell antigens could be introduced into normal rodents at the appropriate time during fetal development, those animals could be rendered tolerant and serve as suitable hosts for human hepatocyte transplants after birth without either genetic or pharmacological generalized immunosuppression. If successful, these animals could serve as convenient animal models for studying mechanisms of human hepatitis viral infections, serve as models for testing new antiviral agents, and as means for testing hepatotoxicity of drugs.

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats, 250 g to 300 g of body mass (Charles River Co., Inc., Wilmington, MA) were maintained on 12 h light-dark cycles, and fed ad lib with standard rat chow in the Center for Laboratory Animal Care at the University of Connecticut Health Center. All animal procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to USDA and NIH animal usage guidelines.

Cryopreserved human primary hepatocytes were obtained from Clonetics Corp. (Walkersville, MD) and kept in liquid nitrogen until use. Frozen cells were thawed, washed with human hepatocyte medium (Clonetics Corp.) plus 5 g·L-1 insulin and 0.39 mg·L-1 dexamethasone, and then spun at 50 × for 10 min at 4 °C. Cell viability was measured by trypan blue exclusion staining (approximately 65% of the cells were viable, and 90% were parenchymal hepatocytes). Human hepatoblastoma cell lines Huh7 and HepG2, human fibroblast IMR-90 and human kidney 293 cells were grown in Dulbecco Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 100 mL·L-1 fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics.

At 15 d to 17 d of gestation, groups of pregnant rats were anesthetized by intramuscular injections of ketamine (40 mg·g-1 body mass) and xylazine (5 mg·g-1 body mass). Laparatomies were performed under sterile conditions; gravid uteri were exposed, and transilluminated by a high intensity lamp (Fiber-lite MI-150, Dolan-Jenner Industries, Lawrence, MA). Human hepatocytes or Huh7 cells, 1 × 105 cells in 10 μL PBS, were injected through the uterine wall into the peritoneal cavities of rat fetuses using a sterile 200 μL Hamilton syringe with a 28 gauge beveled point needle (Hamilton Inc., Reno, NV).

Within 24 h of birth, newborn rats were placed on ice for 2-5 min. Under sterile conditions, left paracostal incisions were made, and primary human hepatocytes or Huh7 cells, 1 × 1010 cells made, and primary human hepatocytes or Huh7 cells·L-1 in 200 μL PBS were injected over 30 into the spleen by sterile Hamilton syringe.

Peripheral blood samples were drawn from tail veins, spun, and serum stored at -20 °C. Liver samples were collected either by sacrificing animals or by performing partial hepatectomies. Samples were fresh frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C.

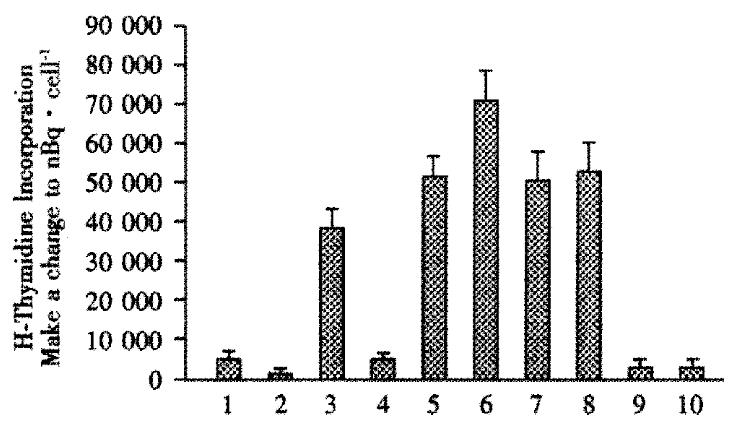

The tolerance of host animals towards human hepatocytes was assessed by mixed lymphocyte assays in which the proliferation of host spleen cells was measured after exposure to exogenous antigens[12]. Briefly, spleens were removed from tolerized or control animals, 1 wk after cell transplantation or for non-transplanted controls one week after birth, and dispersed into RPMI1640 medium (Gibco-BRL) with 50 mL·L-1 FBS. Stimulator cells (primary human hepatocytes, Huh7, IMR-90 and 293 cells) were gamma irradiated with 20Gy to inhibit proliferation. Irradiated stimulator cells, 0.5 mL of 3 × 108·L-1, were mixed with 0.5 mL of 1 × 109·L-1 rat spleen cells, pulse-labeled with 37 kBq of 3H-thymidine (2960TBq·mol-1, Amersham Life Science), and then incubated at 37 °C with 50 mL·L-1 CO2 for 72 h. After trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation, cells were harvested onto Whatman glass fiber filter papers (Whatman), washed successively with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), TCA and ethanol. Filter papers were counted in a scintillation counter (Tri-CARB 4530, Parkard). Spleen cells from untreated rats as well as stimulator cells incubated alone served as controls. All experiments were performed with triplicate animals, and the results expressed as -x±sx in units of nBq·cell-1.

To detect human hepatocytes that survived transplantation in rat livers, human albumin gene sequences were sought as specific markers using a 5' primer (5'-CTGGTCTCACCAATCGGG-3') and a 3' primer (5'-CTGGTCTCACCAATCGGGGG-3'). Genomic DNA extracted from Huh7 cells served as a positive control. Genomic DNA from untreated rats, and rats tolerized without transplantation were used as negative controls.

To quantify the number of human hepatocytes present in rat livers, dot blots using probes specific for the human albumin gene were performed by modifying the method of Kafatos[13] with a 32P-labeled 1750 bp BamH I/Bste II human albumin DNA fragment excised from palb 3, a plasmid containing the complete human albumin gene[14]. All assays were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as -x±sx. Genomic DNA from known numbers of Huh7 cells was measured in an identical fashion.

To determine whether transplanted human hepatocytes retained liver-specific transcription, the presence of human albumin mRNA was sought by RT-PCR after extraction according to the method of Chomczynski[15] using primers for human albumin (sense 5'-CCTTGGTGTTGATTGCCTTGCTC-3', antisense 5'-CATCACATCAACCTCTGGTCTCACC-3') and rat albumin (sense 5'-CGGTTTAGGGACTT-AGGAGAACAGC-3', antisense 5'-ATAGTGTCCCA-GAAAGCTGGTAGGG-3'). The expected size of PCR products for human and rat albumin mRNA were 315 bp and 388 bp, respectively.

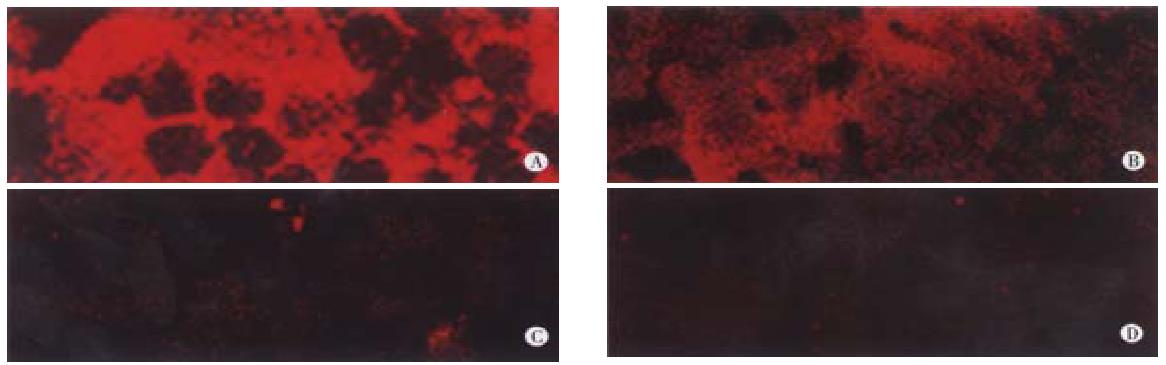

Sixteen weeks post-transplantation, groups of rats were sacrificed, and livers sectioned into 5 μm slices in tissue freezing medium (Triangle biomedical Sciences, Durham, NC). Immunofluorescence staining was performed using a modification of the method of Osborn[16] using monoclonal mouse anti-human albumin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and goat anti-mouse IgG second antibody conjugated with Texas Red (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Immunohistochemical staining for human albumin was done according to the method of Kieran[17]. Tissue samples were examined using confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM-410, Zeiss, Germany).

To measure human albumin in rat serum, Western blotting was performed in a manner similar to the method of Gershoni[18] using monoclonal mouse anti-human albumin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and rabbit anti-mouse IgG second antibody conjugated with horseradish perioxidase (HRP) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The signal was detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence method (ECL kit, Amersham) and exposed to film.

Mixed lymphocyte assays were used to detect changes in immune response as a result of intrafetal injections. In these assays, spleen (responder) cells taken at wk1 after birth were mixed with irradiated stimulator cells (primary human hepatocytes, or controls consisting of Huh7 human hepatoblastoma cells, IMR-90 human fibroblasts, or 293 human kidney cells). Figure 1, lane 1 shows that spleen cells from animals that were not injected with hepatocytes intrafetally, incubated alone (without any stimulator cells) had baseline uptake of (1446 ± 111) nBq·cell-1. Irradiated hepatocytes incubated alone only took up (222 ± 100) nBq·cell-1. Lane 2, in contrast, the spleen cells from lane 1, from rats with no intrafetal injection, but subsequently exposed to irradiated human hepatocytes, lane 3, were stimulated to take up (10842 ± 1585) nBq·cell-1, a 7.5-fold increase. But, when spleen cells from rats that had intrafetal injection of primary human hepatocytes, were subsequently exposed to irradiated primary human hepatocytes, lane 4, they were not stimulated as uptake was only (1390 ± 139) nBq·cell-1. To determine whether the lack of stimulatory effect was hepatocyte-specific, spleen cells from animals injected intrafetally with primary hepatocytes were exposed to human IMR-90 fibroblasts. In contrast to hepatocyte stimulator cells, the spleen cells were stimulated by the fibroblasts, taking up (14373 ± 1473) nBq·cell-1, lane 5, which was similar to the uptake of cells from rats not intrafetally injected with hepatocytes, (13956 ± 2085) nBq·cell-1, lane 7. In another control, uptake by 293 human kidney cells was also stimulated in spleen cells from rats either intrafetally injected with hepatocytes, lane 6, or not, lane 8. Irradiated IMR-90, lane 9, and 293 cells, lane 10, incubated alone had negligible uptake, indicating that the contribution of these cells could not account for the observed increases in uptake results found in lanes 5 and 7.

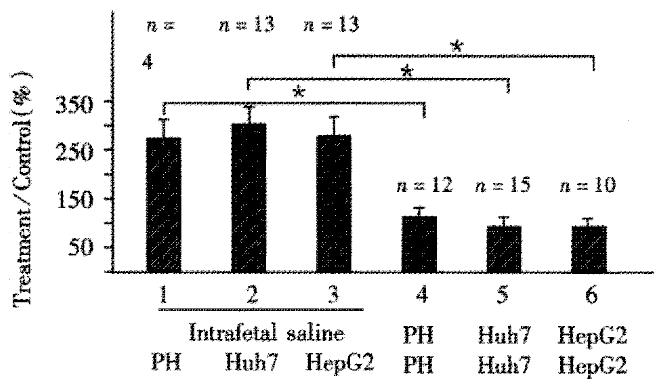

To determine whether transformed human hepatocytes could be also used to induce immunological tolerance, Huh7, and HepG2 human hepatoblastoma cell lines, were compared to primary human hepatocytes in terms of induction of tolerance. Figure 2 shows that spleen cells from rats not injected intrafetally with hepatocytes, and subsequently exposed to primary hepatocytes, lane 1; Huh7 cells, lane 2; or HepG2 cells, lane 3 all had uptake ratios significantly and substantially greater than cells from rats intrafetally injected and subsequently exposed to the corresponding cells, lanes 4, 5 and 6, respectively.

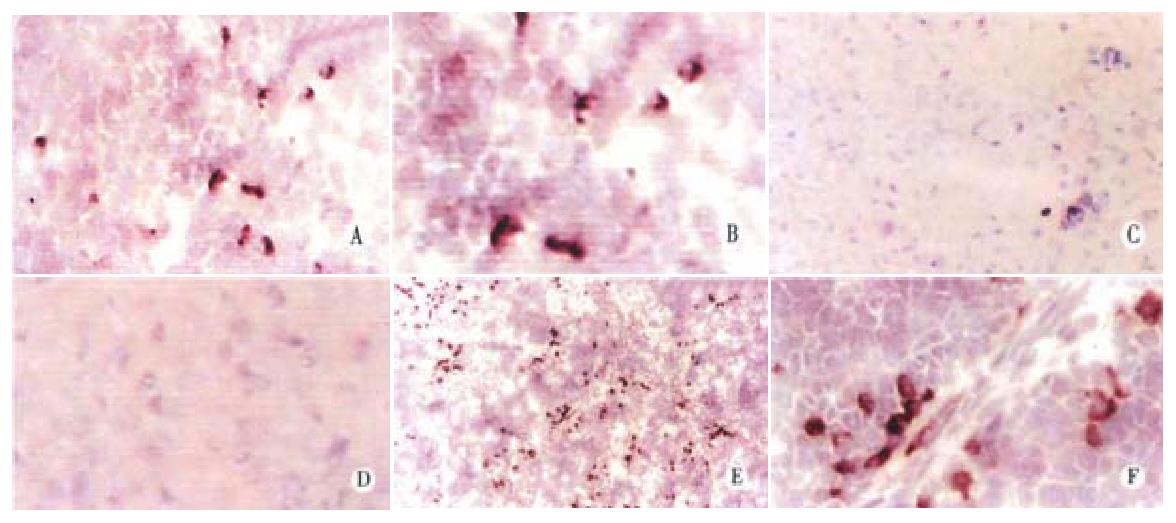

Because of the difficulty in obtaining primary human hepatocytes, immunohistochemical methods for detection of transplanted cells were established using Huh7 hepatoblastoma cells. To visualize these cells in livers of rats that were previously tolerized intrafetally and transplanted with Huh7 cells, staining with monoclonal mouse antibody against human albumin was performed. Figure 3 shows that staining was detectable in rat livers on day 1 after transplantation mostly as single cells, but with occasional pairs, fairly evenly distributed throughout the parenchyma, panel A and with high magnification, panel B. Seven days after birth, clusters of 2 and 3 cells each were visible, and single cells less common, panel E and with higher magnification, panel F. No human albumin was detected in rats that were tolerized with Huh7, but were not transplanted, panel C and at higher magnification, panel D, confirming that the antibody was specific for human albumin and lacked cross reactivity with endogenous rat albumin.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy was used to visualize transplanted hepatocytes by staining with monoclonal antibody against human albumin. Figure 4 shows that in tolerized rats transplanted with human hepatocytes, human albumin was detected at week 16 post-transplantation, panel B. In tolerized rats without transplantation, no staining was detected, panel C. Rat liver sections stained with secondary antibody alone, panel D demonstrated that the staining was not an artifact due to non-specific interaction with second antibody. As expected samples stained with monoclonal goat anti-rat albumin antibody, panel A, resulted in positive signals for rat albumin in virtually every parenchymal cell in the liver.

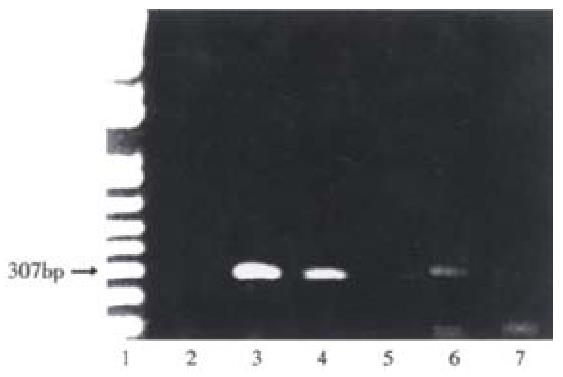

To estimate of the number of human hepatocytes present in rat liver transplanted with human hepatocytes, human albumin DNA sequences were detected by amplification of rat liver genomic DNA by PCR. Figure 5, lanes 3-5 show human albumin DNA extracted from 104, 103 and 102 Huh 7 cells, respectively. PCR produced expected 307 bp products with decreasing intensities of signals. DNA from a rat intrafetally injected with primary human hepatocytes and transplanted with those cells, lane 6 produced a band at the expected position. In contrast, a littermate intrafetally injected with human hepatocytes, but without hepatocyte transplantation, lane 7, produced no detectable human albumin DNA signal. Bands at the bottom of the gels are due to excess primers. Neonatal rats sustained intrasplenic transplantation of human hepatocytes well, with a mortality rate of about 5%.

To quantitate the amount of human albumin gene present, dot blotting for human albumin DNA was performed. In Figure 6, the upper row of panel A, shows that liver samples from a representative rat intrafetally injected and transplanted with primary human hepatocytes had positive signals for human albumin DNA at 6 wk and 16 wk post-transplantation, with little obvious change in signal between the time points. In contrast, a littermate tolerized with human hepatocytes, but not transplanted, lower row, had no signals at the same time points indicating that the human albumin signal detected in the upper panel were not due to residual DNA from the tolerization procedure or cross reactivity with rat sequences. In panel B, the plasmid palb3, was loaded in serial dilutions as standards for human albumin DNA. Based on the amount of human albumin DNA in 10 (g rat liver DNA, the number of surviving human hepatocytes was calculated to be 2.5 × 105 cells per whole adult liver 16 wk post-transplantation. The ratio of human to rat hepatocytes that were present, 16 weeks post-transplantation, was calculated to be approximately 1 human cell per 6 × 103 rat hepatocytes.

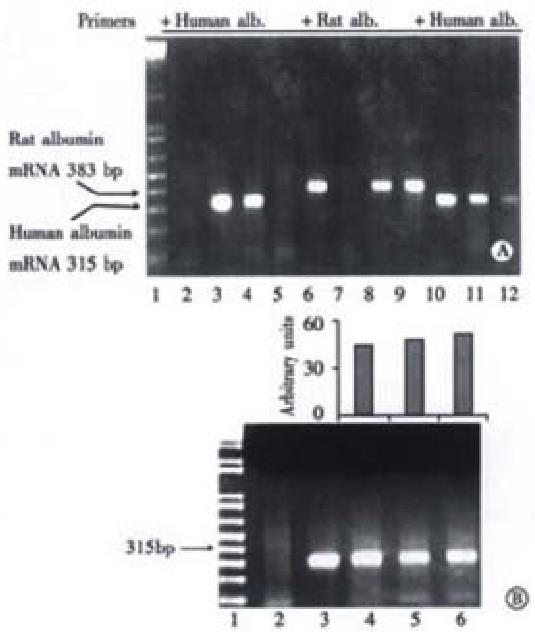

To assess albumin gene transcription in rat livers, RT-PCR of albumin mRNA was performed. In Figure 7, panel A, lane 3 shows that human albumin mRNA extracted from Huh7 cells was detected by RT-PCR by the presence of a product with the expected size of 315 bp. As expected, the same sample failed to generate a signal when rat albumin primers were used indicating that the human primers were specific for the detection human albumin mRNA, lane 7. In tolerized rats 16 wk after human hepatocyte transplantation, human albumin mRNA was also detected as a 315 bp band, lane 4. However, no human albumin mRNA was detected in a littermate intrafetally injected, but without transplantation, lane 5, or from a non-fetally injected, and non-transplanted rat, lane 2. However, a band corresponding to the rat albumin amplification product of 388 bp was demonstrated in a representative rat neither intrafetally injected, nor transplanted, lane 6; a rat intrafetally injected, and transplanted, and sampled 16 weeks after transplantation, lane 8; and a rat intrafetally injected, but without transplantation, lane 9. As standards, RNA extracts from Huh7 cells were amplified with primers for human albumin, and as expected produced decreasing signals of 315 bp products, lanes 10-12.

The transcriptional activity of transplanted human hepatocytes as a function of time was measured over the entire experimental period of 16 wk. Figure 7, panel B, lane 3 shows that human albumin mRNA extracted from Huh7 cells in culture and detected by RT-PCR produced a product with the expected size of 315 bp. Human albumin mRNA levels from rats were not obviously different at wk2, 6, and 16 after transplantation, lanes 4, 5 and 6, respectively, suggesting that, within the limits of the assay, the function of transplanted human hepatocytes, at least with regard to albumin production, remained unchanged for at least 16 weeks.

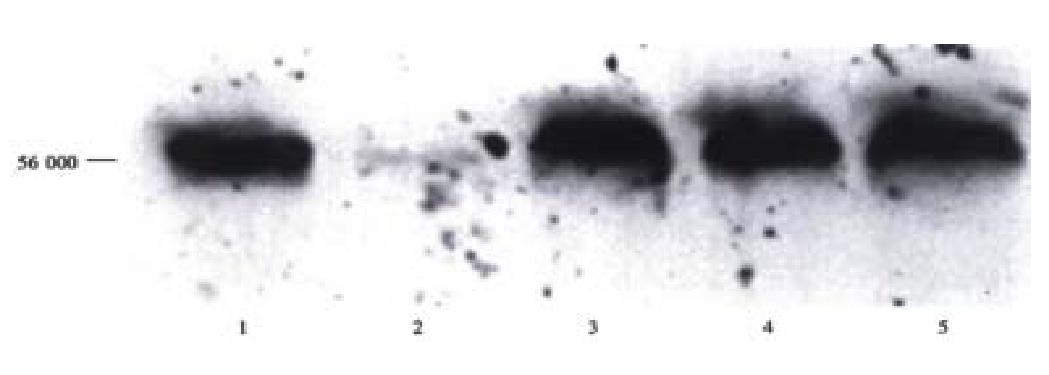

Figure 8 shows Western blots of serum from a representative rat tolerized and transplanted with primary human hepatocytes. A band with migration corresponding to 56 ku, the expected size of human serum albumin, as shown by standard human albumin in lane 1 was found in serum from a rat intrafetally injected and transplanted with primary human hepatocytes 1 wk post-transplantation, lane 3, and remained detectable at 2 and 3 wk post-transplantation, lanes 4 and 5, respectively. There was no cross reactivity of antibody with rat liver not transplanted with human cells as shown in lane 2. These data support the conclusion that human hepatocytes can be transplanted, and survive in the livers of intrafetally tolerized rats, and remain sufficiently active to secrete detectable amounts of human serum albumin into the circulation.

The developing immune system in the fetus allows a unique opportunity for the induction of tolerance to specific cells without generalized suppression of the immune system. In utero injection of donor cells directly into the peritoneal cavities of fetuses during gestation has been shown previously to result in a donor-specific tolerance[10,11,19]. With regard to the timing of cell injections for induction of tolerance, previous studies in normal mice demonstrated that in utero injections of splenocytes on days 14 to 16[20] were satisfactory for induction of donor-specific tolerance and prolongation of the survival of allogeneic skin grafts. In our experiments, intrafetal injections performed on any of three days, from day 15 to 17 of gestation, resulted in equal effectiveness in establishing tolerance to human hepatocytes.

Livers of tolerized rats transplanted with human hepatocytes was found to contain the human albumin gene up to 16 weeks post-transplantation, the duration of the experiment, Figure 5 and Figure 6. The transplanted cells were functional as indicated by the presence of human albumin mRNA, Figure 7, and human albumin gene product, Figure 4 and Figure 8. The presence of antibodies to human albumin was not detected (data not shown).

Chimeric liver models have been described previously, but in immunocompromised hosts. For example, normal adult woodchuck hepatocytes were transplanted into uPA/RAG2 knock out mice via intrasplenic injection. These cells eventually reconstituted 90% of those mouse livers[6]. Similarly, immortalized primary human hepatocytes have been transplanted into RAG-2 knock out mice[7]. Recently, primary human hepatocytes were transplanted under the kidney capsule of SCID/NOD mice[8]. The results demonstrate that when transplanted into immunocompromised hosts, human hepatocytes can not only survive, but also maintain differentiated cellular function in foreign hosts and even in unnatural locations. Our current data further indicate that general immune deficiency or suppression is not required, and intrafetal tolerization is sufficient to prevent rejection. Furthermore, the technique could be used to generate tolerance to other cell types, that might result in development of other useful animal models.

The mechanism of tolerance induction via intrauterine exposure to foreign antigen has been ascribed to T-cell clonal deletion[20]. Recently, Knolle and colleagues[21,22] described another method of inducing tolerance in the liver to foreign antigens: direct injection of foreign antigens into portal circulation resulted in the presentation of foreign antigens by liver endothelial cells to CD8+ T-cells. Such a model for tolerance has not been tested specifically for induction of tolerance to xenografted human hepatocyte transplantation.

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIDDK: DK-42182 (GYW), Connecticut Innovations, Inc. (CHW), and the Herman Lopata Chair in Hepatitis Research (GYW). The authors would like to thank Dr. Thiruchandurai V. Rajan for kind co-operation in animal surgery, Ms. Nancy Ryan for assistance in preparing tissue sections, and Dr. Ravi Kondapalli for technical assistance.

Edited by Pan BR

| 1. | Bumgardner GL, Heininger M, Li J, Xia D, Parker-Thornburg J, Ferguson RM, Orosz CG. A functional model of hepatocyte transplantation for in vivo immunologic studies. Transplantation. 1998;65:53-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bumgardner GL, Li J, Heininger M, Ferguson RM, Orosz CG. In vivo immunogenicity of purified allogeneic hepatocytes in a murine hepatocyte transplant model. Transplantation. 1998;65:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bumgardner GL, Li J, Prologo JD, Heininger M, Orosz CG. Patterns of immune responses evoked by allogeneic hepatocytes: evidence for independent co-dominant roles for CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in acute rejection. Transplantation. 1999;68:555-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Galun E, Burakova T, Ketzinel M, Lubin I, Shezen E, Kahana Y, Eid A, Ilan Y, Rivkind A, Pizov G. Hepatitis C virus viremia in SCID--& gt; BNX mouse chimera. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ilan E, Burakova T, Dagan S, Nussbaum O, Lubin I, Eren R, Ben-Moshe O, Arazi J, Berr S, Neville L. The hepatitis B virus-trimera mouse: a model for human HBV infection and evaluation of anti-HBV therapeutic agents. Hepatology. 1999;29:553-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Petersen J, Dandri M, Gupta S, Rogler CE. Liver repopulation with xenogenic hepatocytes in B and T cell-deficient mice leads to chronic hepadnavirus infection and clonal growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:310-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brown JJ, Parashar B, Moshage H, Tanaka KE, Engelhardt D, Rabbani E, Roy-Chowdhury N, Roy-Chowdhury J. A long-term hepatitis B viremia model generated by transplanting nontumorigenic immortalized human hepatocytes in Rag-2-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2000;31:173-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ohashi K, Marion PL, Nakai H, Meuse L, Cullen JM, Bordier BB, Schwall R, Greenberg HB, Glenn JS, Kay MA. Sustained survival of human hepatocytes in mice: A model for in vivo infection with human hepatitis B and hepatitis delta viruses. Nat Med. 2000;6:327-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hajdu K, Tanigawara S, McLean LK, Cowan MJ, Golbus MS. In utero allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to induce tolerance. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1996;11:241-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yuh DD, Gandy KL, Hoyt G, Reitz BA, Robbins RC. Tolerance to cardiac allografts induced in utero with fetal liver cells. Circulation. 1996;94:II304-II307. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Yuh DD, Gandy KL, Hoyt G, Reitz BA, Robbins RC. A rodent model of in utero chimeric tolerance induction. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997;16:222-230. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Schwartz RH, Jackson L, Paul WE. T lymphocyte-enriched murine peritoneal exudate cells. I. A reliable assay for antigen-induced T lymphocyte proliferation. J Immunol. 1975;115:1330-1338. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kafatos FC, Jones CW, Efstratiadis A. Determination of nucleic acid sequence homologies and relative concentrations by a dot hybridization procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1541-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 967] [Cited by in RCA: 1094] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu GY, Wilson JM, Shalaby F, Grossman M, Shafritz DA, Wu CH. Receptor-mediated gene delivery in vivo. Partial correction of genetic analbuminemia in Nagase rats. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14338-14342. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40518] [Cited by in RCA: 39095] [Article Influence: 1028.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Osborn M, Weber K. Immunofluorescence and immunocytochemical procedures with affinity purified antibodies: tubulin-containing structures. Methods Cell Biol. 1982;24:97-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kieran J. Histological and histochemical methods: theory and practice. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann. 1990;. |

| 18. | Gershoni JM, Palade GE. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to a positively charged membrane filter. Anal Biochem. 1982;124:396-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kline GM, Shen Z, Mohiuddin M, Ruggiero V, Rostami S, DiSesa VJ. Development of tolerance to experimental cardiac allografts in utero. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57:72-74; discussion 75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim HB, Shaaban AF, Milner R, Fichter C, Flake AW. In utero bone marrow transplantation induces donor-specific tolerance by a combination of clonal deletion and clonal anergy. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:726-729; discussion 726-729;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Limmer A, Ohl J, Kurts C, Ljunggren HG, Reiss Y, Groettrup M, Momburg F, Arnold B, Knolle PA. Efficient presentation of exogenous antigen by liver endothelial cells to CD8+ T cells results in antigen-specific T-cell tolerance. Nat Med. 2000;6:1348-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 540] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Knolle PA, Gerken G. Local control of the immune response in the liver. Immunol Rev. 2000;174:21-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |