Published online Jun 15, 2001. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i3.308

Revised: April 3, 2001

Accepted: April 15, 2001

Published online: June 15, 2001

- Citation: Appleyard MN, Swain CP. Endoscopic difficulties in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2001; 7(3): 308-312

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v7/i3/308.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v7.i3.308

Bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract remains common, with a reported annual incidence of up to 172 per 100000[1], which has if anything increased from earlier series. Case fatality was recently reported as 14%[2], which has probably not changed over several decades. These figures may reflect a rising proportion of elderly patients and increasing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory use, but occur despite apparently better treatments and understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of peptic ulcer disease. Of patients in whom a diagnosis is confirmed, more than 90% suffer from Peptic Ulcers, oesophageal or gastric malignancy, varices, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, erosive disease and oesophagitis[1,2]. This report will focus on the some of the less common aetiologies of upper GI bleeding which are sometimes difficult to identify at endoscopy.

Gastrointestinal angiodysplasia are the most common cause of obscure chronic blood loss from the digestive tract with small bowel angiodysplasia accounting for up to 40% of obscure GI bleeding[3]. The pathophysiology is unknown, but has been suggested to result from low grade venous obstruction of submucosal veins as they cross muscle layers[4]. It is said to be more prevalent in chronic renal failure patients[5]and in patients with aortic stenosis, although, recent reports have failed to confirm this link[6]. Isolated gastric angiodysplasia commonly occurs on the greater curve of the body (Figure 1), whereas small bowel angiodysplasia are often multiple and widespread but may cluster in the proximal jejunum.

Osler-Weber-Rendu Syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by angiodysplastic lesions involving the skin, mucosal membranes and organs other than the GI tract (Figure 2). Patients present as children or adults with epistaxis and up to 40% develop chronic iron deficiency secondary to GI bleeding usually after the age of 50. Their endoscopic appearance is indistinguishable from other angiodysplastic lesions, but they tend to be more widespread.

Acquired angiodysplastic like lesions such as those due to radiation damage can also lead to upper GI bleeding.

Various thermal coagulation devices, including heater probes, bipolar probes, the Nd:YAG laser and the argon plasma coagulator appear to be successful in treating these lesions. Coagulation should begin at the central feeding arteriole and work peripherally. Bleeding is common during treatment and usually self limiting. The depth of injury should be minimized, especially in the small bowel and right colon, in order to avoid either frank perforation, or the post-coagulation syndrome, in which patients develop rebound tenderness without detectable intraperitoneal gas. Laser treatment can cause deep injury relatively easily and must be used carefully. Our primary treatment modality is the bipolar probe because it causes more superficial injury than other thermal methods. Complication rates are low for gastric lesions and although no data exists, are also thought to be low in the small bowel. Colonic complications after laser therapy have been reported in up to 10% cases and include partially treated lesions and perforation. Treatment is not required for incidental lesions. Treatment of isolated gastric lesions will often terminate bleeding, whereas treatment of small bowel lesions can more often only hope to reduce transfusion requirements since many lesions are not reached and treated and new lesions will develop with time. The frequency of further endoscopic treatment sessions depends on clinical assessment, rate of recurrence of anaemia and transfusion requirements. Some patients will maintain a stable haemoglobin on iron therapy alone. A placebo-controlled trial mainly in patients with Osler Weber Rendu disease demonstrated decreased transfusion requirements in patients taking 0.05 mg ethinyl oestradiol and 1.0 mg of norethindrone daily[7].

Dieulafoy's lesion is a cause of diagnostic difficulty in patients with repeated haematemesis; the exposed, eroded vessel in a very small ulcer is difficult to spot at endoscopy (Figure 3) and accounts for perhaps 2% of upper GI bleeds[8]. It was described in detail by Dieulafoy in 1896[9], who described "xulceratio Simplex": bleeding from a simple acute submucosal ulcer of small size. Histology demonstrates an artery with a diameter of 1-3 mm usually surrounded by a small ulcer, less than 5 mm in diameter. Often no inflammation, sclerosis or aneurysmal dilatation is seen. The aetiology is uncertain with most cases occurring in the elderly. NSAIDS and Helicobacter pylori have not been implicated. Patients usually present with significant upper GI haemorrhage. The lesions endoscopically are commonly located high on the posterior aspect of the lesser curve within 3 cm of the gastro-oesophageal junction, but similar lesions have been identified throughout the GI tract. They are often difficult to see when not actively bleeding. Adequate inflation to distend the folds in the upper stomach, a retroflexed endoscope and close examination of the mucosa posteriorly on the lesser curve may help to identify this entity. Multiple examinations are commonly required and the abnormality is sometimes diagnosed when pulsatile arterial bleeding is seen coming from apparently normal mucosa. Endoscopic therapy is successful in more than 90% of cases. Adrenaline is frequently injected into the base prior to definitive treatment with electrocoagulation or, more recently, band ligation.

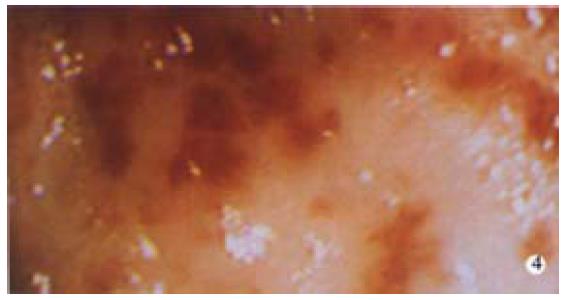

This syndrome is a rare cause of GI bleeding, although increasingly recognized. It was first described in 1952 by Rider et al and used to be called gastric antral vascular ectasia. Jabbari et al[10] coined the phrase "atermelon stomach" to describe the endoscopic features: visible columns of vessels traversing the antrum in longitudinal folds converging on the pylorus and resembling the stripes of a watermelon (Figure 4). There is often marked mucosal and submucosal thickening which has been demonstrated with endoscopic ultrasound. It is said to occur more commonly in women, 71% in the largest series[11], with the mean age of presentation being 73 in women and 68 in men. Approximately 90% of patients present for evaluation of occult bleeding and persistent iron deficiency anemia, which characteristically fails to respond to iron therapy. Up to 62% of patients have associated autoimmune or connective tissue diseases, the most common being the CREST syndrome and pernicious anemia, which can confusingly normalize the mean corpuscular volume. Atrophic gastritis seems almost invariable with the majority having achlorhydria and hypergastrinaemia. Cirrhosis and portal hypertension occurs in up to 60% in some series, but is not a feature in more recent series. This lesion can be confused with portal hypertensive gastropathy. The diagnosis is usually made endoscopically if the characteristic lesion is seen. However, histology can help demonstrate the vascular nature of the disorder, with dilated and thrombosed laminar propria capillaries with reactive fibromuscular hyperplasia. It has been suggested that watermelon stomach arises from traumatic gastric peristalsis in a similar fashion to that seen in other prolapse syndromes such as stoma sites, solitary rectal ulcer and haemorrhoids. Excellent long term results have been reported with the use of endoscopic therapy. Nd: Yag laser has been the most studied with an average of 3-4 sessions being required to ablate visible disease and terminate transfusion requirements in over 90% of cases in follow up of up to 6 years. Other treatments such as bipolar or heater probes and the argon plasma coagulator, have also been shown to be successful. However, Nd: Yag laser, which can be used to "paint" the stripes of the watermelon, may require fewer treatments due to its increased depth of injury. Surgical antrectomy has also been reported to be successful, but is rarely necessary since endoscopic therapy is highly effective. Pharmacological agents such as steroids and 5-hydroxytryptamine antagonists have been used in small numbers of patients in uncontrolled trials with perhaps some success. Recognition of this characteristic lesion is important since it is commonly dismissed by less experienced endoscopists as antral gastritis.

Erosive disease is an uncommon cause of severe upper GI bleeding; however, some lesions warrant mentioning as they are often overlooked or missed at endoscopy. Cameron erosions were described by Cameron and Higgins as chronic linear erosions positioned on the crests of folds at the diaphragmatic impression in one-third of 109 patients with a large hiatus hernia[12]. They suggested that the erosions were caused by the mechanical trauma of the folds rubbing together during diaphragmatic movement with breathing (Figure 5) and the erosions were more common in patients with anaemia, perhaps due to blood loss from these erosions.

Prolapsing gastropathy is a syndrome characterized endoscopically by a focal area with subepithelial haemorrhage and, occasionally, erosions within a few centimeters of the cardioesophageal junction. This mucosal area may be seen to be the apex of a knuckle of gastric mucosa, most commonly coming from the 10 o'clock position which prolapses into the distal oesophagus during retching, often prior to haematemesis. Shepherd et al[13] described the histological features at endoscopic biopsy of 21 cases of prolapsing gastropathy, describing inflammation in 85%, submucosal haemorrhage in 38% and superficial ulceration in 10%.

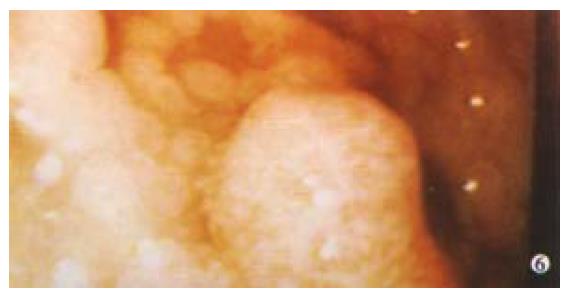

Adenocarcinoma accounts for 90% of gastric tumours with lymphoma accounting for 5%, stromal tumours 2% and the rest including carcinoids, metastases and others. GI involvement occurs in 50% of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, with the stomach being the most common extranodal site. 95% of gastric lymphomas are non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Lymphomas are often clinically silent early on, but progress to signs and symptoms of advanced gastric cancer including upper GI bleeding. Endoscopically lymphomas have a wide range of different appearances and may present as enlarged gastric folds, mucosal nodularities, multiple polypoid masses with or without ulceration, or with a diffuse infiltrative process (Figure 6). One unusual feature is that peristalsis is often preserved. Diagnosis can be difficult, sometimes requiring full thickness biopsy, but when combined with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) diagnostic accuracy approaches 100%. Treatment is according to histology and includes helicobacter eradication for MALT lymphomas.

Stromal tumours such as leiomyomas tend to be indolent and slow growing, but can be aggressive. They most commonly present with GI blood loss, and are occasionally ulcerated but often appear entirely submucosal at endoscopy (Figure 7) and conventional biopsy usually fails to make the diagnosis. EUS and deep biopsy can assist in making the diagnosis. Surgical management should be considered for large gastric lesions of this type: small oesophageal stromal cell tumours seem to have a low incidence of malignant change. Carcinoid tumours only rarely cause GI bleeding. Like stromal cell tumours they are often submucosal requiring deep biopsies to make the diagnosis. Kaposi's sarcomas do not tend to bleed as much as their vascular appearance would suggest, but may bleed especially if the patient has a low platelet count. Multiple tumours metastasize to the stomach causing bleeding: these include secondary melanoma, and cancer of the breast, lung, ovary, colon, liver and testes. Melanoma lesions can have a characteristic bullseye appearance or more rarely be amelanotic. Primary renal cancer on the right side can erode and bleed into the duodenum. A common problem with bleeding tumours is the diffuse, often friable area that needs to be treated. Endoscopic treatment of these lesions is often unrewarding, but includes the use of laser, argon plasma coagulator and injection of alcohol. Definitive treatment with resection is sometimes helpful in selected patients and some tumours are radiosensitive.

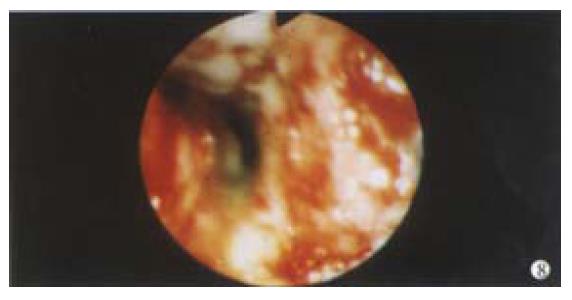

There are some other rare vascular lesions that can cause GI bleeding. The Blue Rubber Bleb Naevus Syndrome is an example of intestinal haemangioma which is an autosomal dominant condition causing GI bleeding in infants and children. These lesions are raised blue vascular lesions that can be multiple in the bowel associated with similar cutaneous lesions. The endoscopic lesions are usually redder in colour than the dark blue lesions seen on the skin. Endoscopic therapy has been successfully used, but care needs to be taken since the lesions can be transmural: some authors suggest that endoscopic therapy should be used only intraoperatively. Rarely, conditions involving the blood vessel itself can lead to bleeding. Connective tissue diseases such as pseudoxanthoma elasticum, vasculitis and infiltrating conditions such as amyloid all affect the integrity of the blood vessels resulting in bleeding (Figure 8).

Bleeding from either the biliary tree (haemobilia) or from the pancreatic duct (Wirsungorrhagia) into the duodenum can be difficult to identify and may require the use of a side-viewing endoscope to make the diagnosis. In earlier series, the most common cause of haemobilia was accidental trauma, accounting for 40%, with operative trauma, systemic infection, gallstone disease and aneurysms roughly contributing 15% each. Recent series indicate iatrogenic trauma accounting for 40% and accidental trauma 20%[14]. Classically, patients present with the triad of pain, jaundice and melaena, although only 40% of patients present in this way. A history of chronic pancreatitis or pseudocyst may be a pointer to a bleed from the pancreatic duct. Asymptomatic melaena and haematemesis with a normal endoscopic appearance are other recognized presentations. Endoscopically, blood is seen coming from the ampulla in less than 40% of patients and clot in the bile duct or pancreatic duct may be demonstrated during ERCP. It has been suggested that the endoscopic appearance at the ampulla of a filiform clot suggests biliary bleeding and of fresh bleeding a pancreatic origin. Angiographic or CT findings of an aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm or arterio-portal-venous fistula may be needed to make diagnosis. Management is often difficult. Some patients can be managed conservatively. However, if surgery is required 75% of patients can expect haemostasis. Embolization of aneurysms is occasionally effective.

Oesophageal apoplexy is a rare condition presenting with pain and haematemesis after swallowing and a large submucosal haematoma is seen, which can occlude the lumen and may be associated with a mucosal tear.

Conditions such as portal hypertensive gastropathy and aorto-enteric fistulae are only mentioned briefly here. A history of abdominal aortic graft surgery should prompt a careful endoscopic examination of the second and third parts of the duodenum. If aorto-oesophageal fistula is suspected, usually in a patient with a massive bleed and a history of surgery, sepsis or trauma to the thoracic aorta, CT investigation should be undertaken prior to endoscopy in theatre since endoscopy can precipitate torrential bleeding.

Edited by Ma JY

| 1. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Blatchford O, Davidson LA, Murray WR, Blatchford M, Pell J. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in west of Scotland: case ascertainment study. BMJ. 1997;315:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Morris AJ, Mokhashi M, Straiton M, Murray L, Mackenzie JF. Push enteroscopy and heater probe therapy for small bowel bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:394-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jensen DM, Machicado GA. Bleeding Colonic Angioma: Endoscopic coagulation and follow up. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1433. |

| 5. | Chalasani N, Cotsonis G, Wilcox CM. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with chronic renal failure: role of vascular ectasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2329-2332. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gostout CJ. Angiodysplasia and aortic valve disease: let's close the book on this association. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:491-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Cutsem E, Rutgeerts P, Vantrappen G. Treatment of bleeding gastrointestinal vascular malformations with oestrogen-progesterone. Lancet. 1990;335:953-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Reilly HF, al-Kawas FH. Dieulafoy's lesion. Diagnosis and management. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1702-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dieulafoy G. Exulceratio simplex. Bull Acad Med. 1898;39-40,49-82. |

| 10. | Jabbari M, Cherry R, Lough JO, Daly DS, Kinnear DG, Goresky CA. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: the watermelon stomach. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1165-1170. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Gostout CJ, Viggiano TR, Ahlquist DA, Wang KK, Larson MV, Balm R. The clinical and endoscopic spectrum of the watermelon stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:256-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cameron AJ, Higgins JA. Linear gastric erosion. A lesion associated with large diaphragmatic hernia and chronic blood loss anemia. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:338-342. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Shepherd HA, Harvey J, Jackson A, Colin-Jones DG. Recurrent retching with gastric mucosal prolapse. A proposed prolapse gastropathy syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Czerniak A, Thompson JN, Hemingway AP, Soreide O, Benjamin IS, Allison DJ, Blumgart LH. Hemobilia. A disease in evolution. Arch Surg. 1988;123:718-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |