Published online Oct 15, 2000. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i5.770

Revised: September 24, 2000

Accepted: September 28, 2000

Published online: October 15, 2000

- Citation: Alison MR, Leiman G, Kew MC. Metastasis in an axillary lymph node in hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2000; 6(5): 770-772

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v6/i5/770.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v6.i5.770

Although hepatocellular carcinoma often metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, spread to more distant lymph nodes is rare[1-7]. Involvement of axillary lymph nodes by metastases appears not to have been documented. We report a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with a metastasis in a lymph node in the right axilla, and discuss possible routes by which such spread might occur.

M.S., a 28-year-old black African woman presented to the medical service of the Johannesburg Hospital in April 1999 with a 2-month history of worsening pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, increasing abdominal girth, yellow discoloration of the sclerae, and generalized pruritus. She had been hospitalized in Zimbabwe 3 weeks earlier, when an enlarged gland in her right axilla was biopsied. This showed the histological features of a “cancer originating in the liver”. She was told that there was no effective treatment for her disease and was discharged. The patient had previously been well and did not smoke cigarettes or drink alcohol. Since the birth of her only child 5 years earlier, she had been receiving intramuscular injections of Depo-Provera® for contraception.

Physical examination revealed a young woman who was deeply jaundiced and pale, and showed evidence of recent weight loss. Extensive tribal scarification of the skin was evident. She was afebrile. Her blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg, pulse 115/min, and respiratory rate 20/min. She had florid nasopharyngeal candidiasis and shotty generalized lymphadenopathy. A lymph node measuring 3 by 4 cm, which was firm and adherent to adjacent tissues, was present in the right axilla. The overlying skin showed a healing scar. Her liver was enlarged to 10 cm below the right costal margin (total span 22 cm) and was extremely tender, and the surface was smooth. A bruit could not be heard over the liver. Tense ascites was present. Splenomegaly was not obvious and distended abdominal wall veins were not seen. Air entry at both lung bases was reduced, but no adventitious sounds were heard. A grade 2 ejection systolic murmur was heard at the left sternal border. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

A plain X-ray of the chest revealed an abnormally raised right hemidiaphragm, but was otherwise normal. Abdominal ultrasonography confirmed the presence of ascites. The liver was enlarged with a generally coarse echogenic pattern but with areas with a mixed hyperechoic/ hypoechoic pattern. Enlarged regional or para-aortic lymph nodes were not seen and the kidneys were normal.

The serum α-fetoprotein concentration was 150 µg/L (normal less than 20 µg/L). The hemoglobin level was 11 g/dl, total serum bilirubin 94 µmol/L (conjugated bilrubin 49 µmol/L), total protein 77 g/L, albumin 27 g/L, alkaline phosphatase 261 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 418 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 65 U/L, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 365 U/L. Serosanquinous fluid was obtained on ascitic tap, but on malignant cells were seen on cytological examination.

Hepatitis B virus surface and e antigens and IgG antibody to the core antigen were present in the serum. Hepatitis C antigen and antibody were negative. The human immunodeficiency virus Elisa test and Western blot were positive. The CD4 T cell count was 398, and the CD4:CD8 ratio 0.8:1.

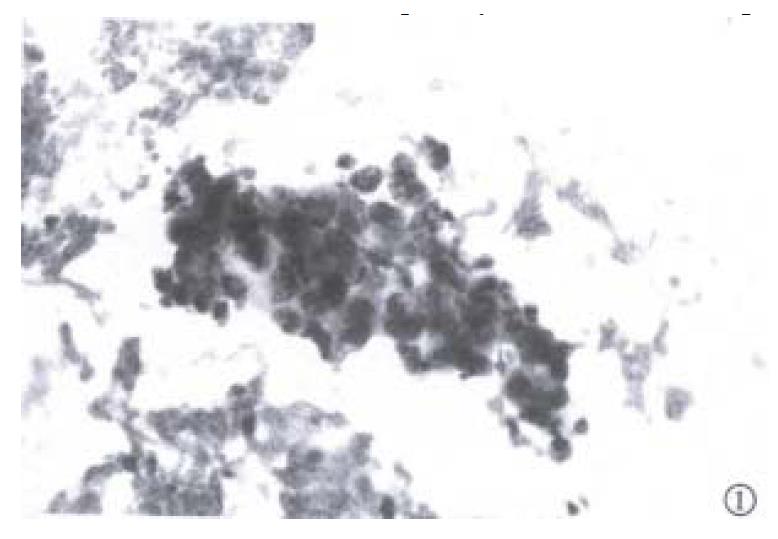

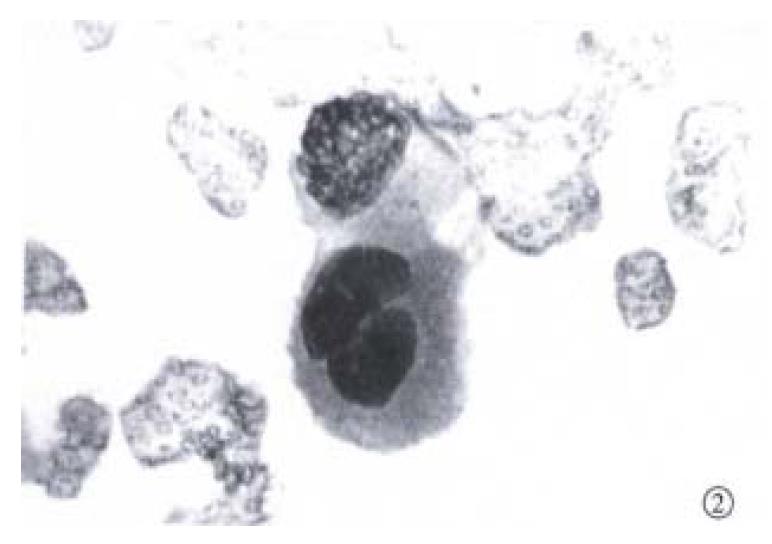

Fine needle aspiration of the enlarged lymph node was performed. Slides were fixed for Papanicolaou staining and air-dried for Diff-Quik staining. Microscopic examination of the slides revealed a background of blood, with moderate numbers of large neoplastic epithelial cells (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The cells were present in both small clusters and as single cells. They were round or oval in outline, and their cytoplasmic margins well defined. The cytoplasm was dense and eosinophilic on the Papanicolaou stain, with a minor population of cells showing cytoplasmic vacuolation. Nuclear cytoplasmic ratios were high, and nuclei centrally located. The nuclei, generally single but very occasionally binucleate, were round, with coarse hyperchromatic chromatin, and very prominent macronuclei. In occasional cell groups, fine capillaries transected the cell a ggregates. These cytological features are in keeping with those found in HCC[8-10]. The alcohol-fixed slide was destained and used for cytochemical analysis. With good positive and negative controls, the cells were found to be negative for both cytokeratin 7 and 20. This cytokeratin profile points to carcinoma cells arising in the liver or kidneys, or to squamous cell carcinoma of the lung[11].

On the basis of the cytomorphology, the metastasis was considered most likely to have arisen in a hepatocellular carcinoma[8-11]. Renal carcinoma of this degree of differentiation would demonstrate eccentric nuclei in less well defined cytoplasm, with finer chromatin than noted here. Squamous cell carcinoma of bronchogenic origin would be unlikely to show the cytoplasmic vacuolation seen in some of these cell groups.

The patient was discharged on palliative treatment, and was subsequently lost to follow up.

Although most patients with HCC present clinically in well defined ways, a large number and wide diversity of unusual presentations have been described[6]. A lack of awareness of these presentations can result in the diagnosis being delayed or even missed. Because we were unaware that HCC can spread to axillary lymph nodes, this diagnosis was initially discounted even though the clinical features were typical in other respects.

A review of the literature reveals no reports of axillary lymph node metastases complicating HCC[1-7]. In particular, four necropsy studies in populations with a high incidence of this tumor (two in Japan[4-7], one in South Africa[1], and one in Hong Kong[3]) and involving more than 1000 patients do not mention this route of spread.

There are two possible routes by which HCC could spread to axillary lymph nodes. The primary tumor in our patient involved most parts of the liver. Tumors located in the upper part of the right hepatic lobe (under the bare area of the liver) could spread via lymphatic vessels to lymph nodes on the upper surface of the diaphragm and thence to either mediastinal or parasternal lymph nodes[12,13]. Malignant cells could then track along intercostal lymphatic vessels to reach the axillary lymph nodes. Spread from mediastinal lymph nodes via intercostal lymphatic vessels is presumed to be responsible for axillary lymph node metastases in bronchogenic carcinoma[14]. Mediastinal glands were not radiologically evident in our patient although based on the experience with bronchogenic carcinoma[14], this does not exclude this mode of spread. Alternatively, malignant cells could spread from the portal venous system to the umbilical region via a patent umbilical vein, or could reach the umbilicus by direct spread from the anterior peritoneum or by lymphatic spread from para-aortic glands invaded by the tumor[15], as shown by the finding of a Sister Joseph’s nodule in an occasional patient with hepatocellular carcinoma[16]. The malignant cells could then drain along subcutaneous lymphatic channels to axillary lymph nodes[17]. The absence of an obvious Sister Joseph’s nodule or even periumbilical induration in our patient makes this route less likely but does not exclude it.

Edited by Ma JY

| 1. | Berman C. Primary Carcinoma of the Liver. London: HK Lewis & Co 1951; 85-98. |

| 2. | Ihde DC, Sherlock P, Winawer SJ, Fortner JG. Clinical manifestations of hepatoma. A review of 6 years' experience at a cancer hospital. Am J Med. 1974;56:83-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ho J, Wu PC, Kung TM. An autopsy study of hepatocellular carcinoma in Hong Kong. Pathology. 1981;13:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakashima T, Okuda K, Kojiro M, Jimi A, Yamaguchi R, Sakamoto K, Ikari T. Pathology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. 232 Consecutive cases autopsied in ten years. Cancer. 1983;51:863-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee YT, Geer DA. Primary liver cancer: pattern of metastasis. J Surg Oncol. 1987;36:26-31. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kew MC. Clinical manifestations and paraneoplastic syndromes in hepatocellular carcinoma. In: Okuda K, Ishak KG (eds). Neoplasms of the Liver. Tokyo: Springer Verlag. 1978;199-214. |

| 7. | Yuki K, Hirohashi S, Sakamoto M, Kanai T, Shimosato Y. Growth and spread of hepatocellular carcinoma. A review of 240 consecutive autopsy cases. Cancer. 1990;66:2174-2179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bottles K, Cohen MB, Holly EM, Chiu SH, Abele JS, Cello JP, Lim RC, Miller TR. Step-wise logistic regression analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma. An aspira tion biopsy study. Cancer. 1988;62:558-563. |

| 9. | Pisharodi LR, Lavoie R, Bedrossian CW. Differential diagnostic dilemmas in malignant fine-needle aspirates of liver: a practical approach to final diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;12:364-370; discussion 370-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salomao DR, Lloyd RV, Goellner JR. Hepatocellular carcinoma: needle biopsy findings in 74 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang NP, Zee S, Zarbo RJ, Bacchi CE, Gown AM. Co-ordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 defines unique subsets of carcinomas. Appl Immunohistochem. 1995;3:99-107. |

| 12. | Moore KL. Clinically oriented anatomy. 2nd Ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins 1980; 231-232. |

| 13. | Snell R. Clinical anatomy for medical students. 2nd Ed. Boston: Little Brown Co 1981; 206. |

| 14. | le Roux BT. Bronchial carcinoma. Edinburgh: Livingstone 1968; 97. |

| 15. | Powell FC, Cooper AJ, Massa MC, Goellner JR, Su WP. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule: a clinical and histologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:610-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Raoul JL, Boucher E, Goudier MJ, Gestin H, Kerbrat P. [Umbilical metastasis of an hepatocellular carcinoma]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1998;22:470-471. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Rains AJH, Ritchie HD. Bailey & Love's Short Practice of Surgery. 16th ed. London: Lewis 1975; 1055. |