Published online Jun 15, 2000. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i3.458

Revised: February 3, 2000

Accepted: March 5, 2000

Published online: June 15, 2000

- Citation: Ji XL, Shen MS, Yin T. Liver inflammatory pseudotumor or parasitic granuloma? World J Gastroenterol 2000; 6(3): 458-460

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v6/i3/458.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v6.i3.458

Liver pseudotumor is a very rare benign lesion. Since the first case reported by Pack and Baker in 1953[1], only 40 cases had been reported up to 1996. The diagnostic challenge of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor is emphasized by the fact that most of the reported cases were diagnosed by surgical procedures.

Pathogenesis and etiology of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor are uncertain. We report a case of hepatic pseudotumor that was suspected to be a well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma based on abdominal ultrasound, CT and MRI, but the final diagnosis is parasitic granuloma of ascariasis larva after hepatic lobectomy.

A soldiery multiple focal hepatic lesion was discovered in a 52-year-old man under the examination of ultrosonography when he was undergoing the regular physical examination in 1998-12. The ultrasonography showed that the nodule appeared as well defined, hypoechoic and hypovascular irregular solid mass without posterior acoustic enhancement on ultrasound (Figure 1). Subsequently, CT scan and MRI also demonstrated the existence of the lesion in the frontal segment of the right hepatic lobe(Figure 2, Figure 3). In January 1999, a fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed on the lesion and the cytological examination showed the possibility of the well differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, the patient underwent the hepatolobectomy on January 12, 1999.

Gross findings: The specimen of partial hepatic lobectomy measured 10 cm × 8 cm × 6 cm in size. The cut surface of the lesion contained several pa le nodules, which were well-defined and slightly hardened. The center of the nodule was soft and pale-brownish in color, but the contour appearance of the surrounded liver was normal.

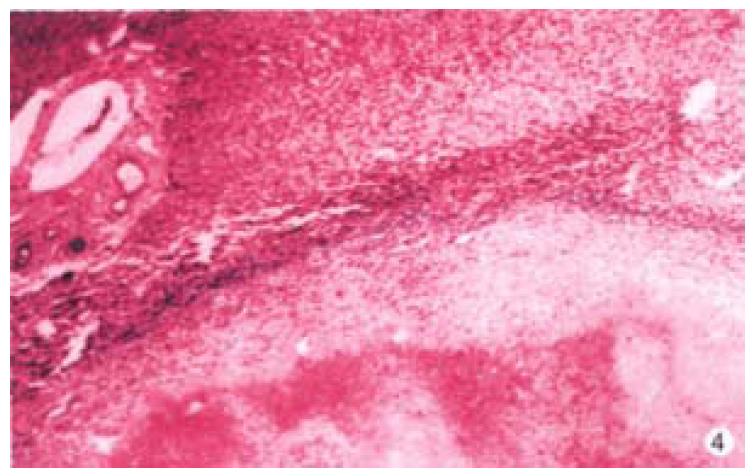

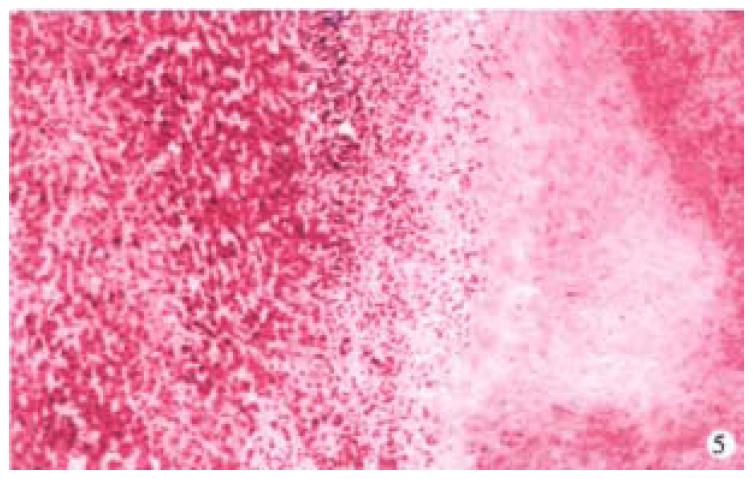

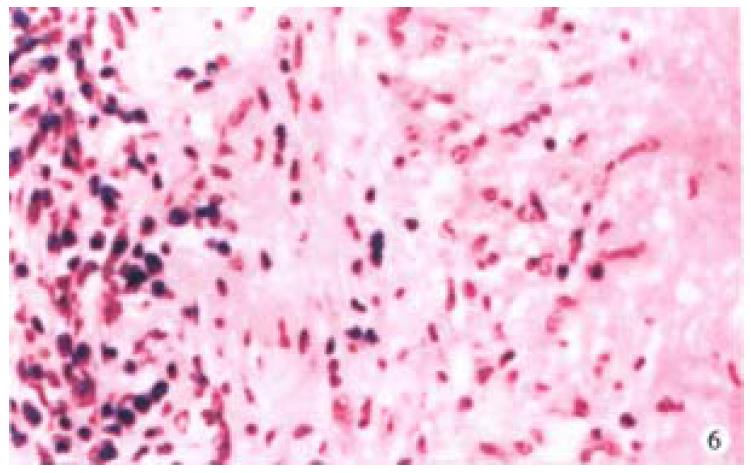

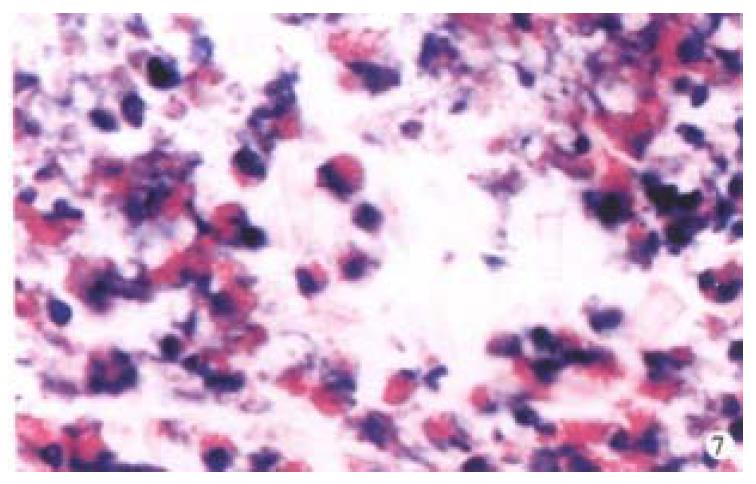

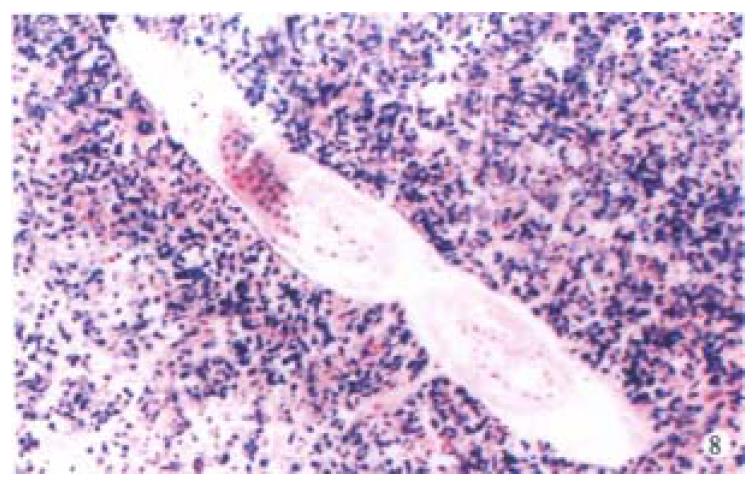

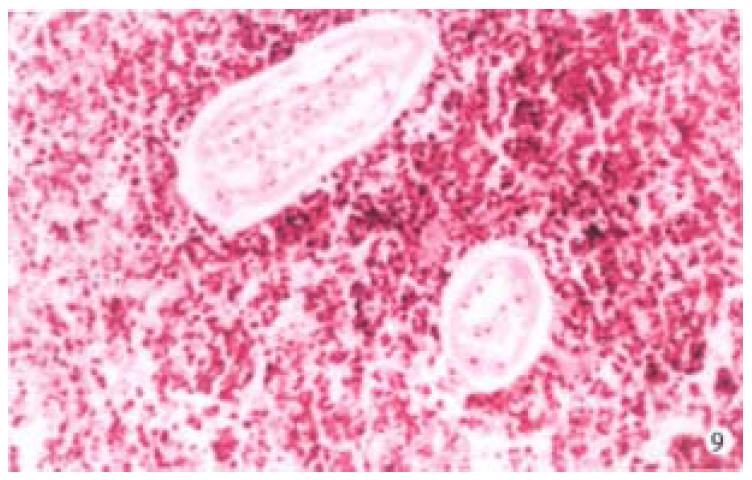

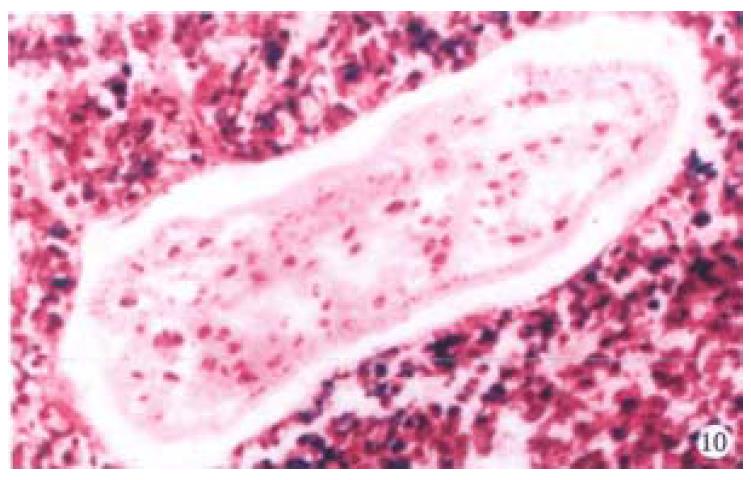

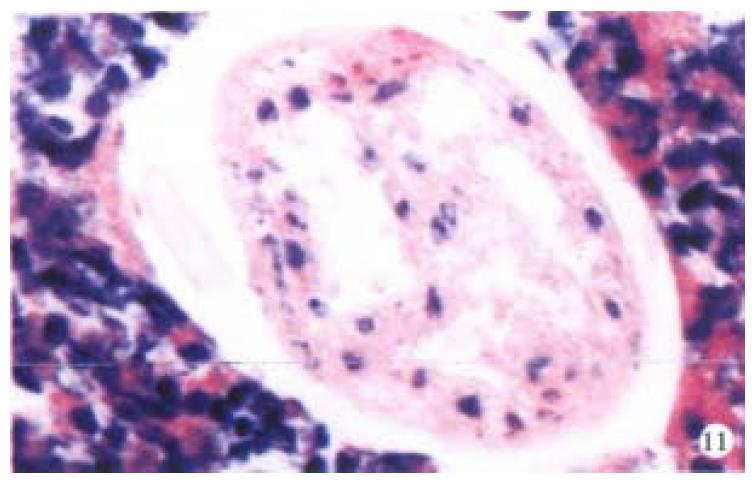

Histopathologic examination. The lesion contained a large are a of necrosis with irregular border (Figure 4), around which there are fibrosis and infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils (Figure 5, Figure 6). In the center of the necrotic lesion, there are many Charcot-Leyden's crystals (Figure 7). The parasite infection was suspected and 26 pieces of tissues from the specimen were sectioned and embedded to find out the pathogen. Finally several parasites with certain morphologic architecture could be found in the sphacelus of the same section (Figure 8, Figure 9) only in one of the slides. Although the cells of the parasites were degene rated or necrosed, the viscus and somatic texture could still be recognized (Figure 10, Figure 11).

Inflammatory pseudotumors are rare benign lesions which may occur in anywhere of the body. They are usually associated with fever, pain and mass formation, and are frequently misdiagnosed as malignant neoplasm. Clinical manifestations and laboratory findings are similar in hepatic pseudotumor and hepatocellular carcinoma. The differential diagnosis between these two is difficult merely base d on the images from ultrasonic and radiological examinations. The diagnostic challenge of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor is emphasized by the fact that most of the reported cases were diagnosed after surgical procedures.

Liver pseudotumors are especially rare and the etiology and pathogenesis are uncertain. Infection was considered as a possible etiology[2]. Only two cases with organisms were reported: Escherichia coli was detected in one case[3], and Gram-positive cocci in the other[4]. Other suggested mechanisms include an immune reaction, liver hemorrhage and necrosis, occlusive phlebitis of hepatic veins, and local reaction to biliary tract[5]. This is the first case in the literature which demonstrated that the ascariasis larva was found in the necrotic focus of the liver and it was primarily diagnosed as inflammatory pseudotumor. It was suggested that more sections should be taken when hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor was suspected.

The life cycle of ascariasis is complex but well understood. Adult male and female worms live in the small intestine, usually the jejunum, where each gravid female worm produces 200000 to 250000 eggs daily. Fertilized egg s pass in the feces and develop into infective eggs in 3 to 4 weeks. The eggs hatch in the small intestine, and the emerging larvae penetrate the intestinal wall, enter t he portal vein or intestinal lymphatic vessels, migrate through the liver to the heart, and are pumped through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs. In the lungs, the larvae break out of capillaries into the air spaces. These larvae migrate up from the bronchi to the trachea and down to the esophagus. In the intestine, the larvae develop into sexually mature adults[6]. From this life cycle, we postulate that the larvae are arrested in the liver during their migration through the liver and become a necrotic nodule.

Xiao-Long Ji, graduated from The Third Military Medical University, specialized in the pathology of gastroenterology, having 250 papers published.

Edited by You DY and Ma JY

proofread by Sun SM

| 1. | PACK GT, BAKER HW. Total right hepatic lobectomy; report of a case. Ann Surg. 1953;138:253-258. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Horiuchi R, Uchida T, Kojima T, Shikata T. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. Clinicopathologic study and review of the literature. Cancer. 1990;65:1583-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Standiford SB, Sobel H, Dasmahapatra KS. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. J Surg Oncol. 1989;40:283-287. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lupovitch A, Chen R, Mishra S. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. Report of the fine needle aspiration cytologic findings in a case initially misdiagnosed as malignant. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:259-262. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gollapudi P, Chejfec G, Zarling EJ. Spontaneous regression of hepatic pseudotumor. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:214-217. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Binford CH, Connor DH. Pathology of tropical and extraordinary diseases: an atlas. Washington D.C. : Armed Forces Instit of Pathol 1976; 463-464. |