Published online Feb 15, 2000. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.49

Revised: December 22, 1999

Accepted: January 4, 2000

Published online: February 15, 2000

AIM: To determine levels of cytokines in colonic mucosa of asymptomatic first degree relatives of Crohn’s disease patients.

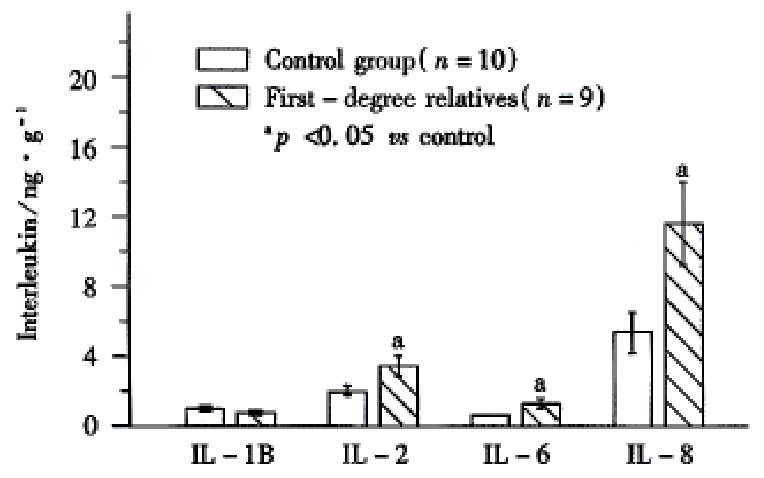

METHODS: Cytokines (Interleukin (IL) 1-Beta, IL-2, IL-6 and IL-8) were measured using ELISA in biopsy samples of normal looking colonic mucosa of first degree relatives of Crohn’s disease patients (n = 9) and fro m normal controls (n = 10) with no family history of Crohn’s disease.

RESULTS: Asymptomatic first degree relatives of patients with Crohn’s disease had significantly higher levels of basal intestinal mucosal cytokines (IL-2, IL-6 and IL-8) than normal controls. Whether these increase d cytokine levels serve as phenotypic markers for a genetic predisposition to de veloping Crohn’s disease later on, or whether they indicate early (pre-cli nical) damage has yet to be further defined.

CONCLUSION: Asymptomatic first degree relatives of Crohn’s disease patients have higher levels of cytokines in their normal-looking intestinal mucosa compared to normal controls. This supports the hypothesis that increased cytokines may be a cause or an early event in the inflammatory cascade of Crohn’s disease and are not merely a result of the inflammatory process.

- Citation: Indaram AV, Nandi S, Weissman S, Lam S, Bailey B, Blumstein M, Greenberg R, Bank S. Elevated basal intestinal mucosal cytokine levels in asymptomatic first-degree relatives of patients with Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2000; 6(1): 49-52

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v6/i1/49.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.49

Numerous studies have proven that cytokines play an integral role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). These protein mediators have been shown to regulate the immune response, induce tissue injury, and mediate complications such as fibrosis and obstruction in patients with IBD[1]. In our institution, we have measured cytokines IL-1B (Interleukin-1 Beta), IL-2, IL-6, and IL-8 from mucosal biopsies obtained during colonoscopy in patients with IBD and other colitides to see if there is any predictive pattern of cytokine el evation[2-5]. Since there is evidence for a genetic predisposition in I BD[6-10], we were also interested in determining if asymptomatic first -degree relatives of Crohn’s disease (CD) patients exhibit elevated intestinal mucosal cytokine levels as well. If they do, is there any pattern to the cytokine elevations?

To our knowledge, there are no studies examining specific cytokine levels in first-degree relatives. Some studies suggest there is increased intestinal permeability in healthy relatives of CD patients[11-14], pointing to a possible genetic defect in these patients. This study may add that even in asymptomatic relatives, there is evidence of subclinical expression of the disease at a cellular level. Elevated cytokine levels would also support the hypothesis that cytokines are a cause or an early event in the inflammatory cascade of CD and not a result of the inflammatory process, since these patients have no pathological signs or symptoms of disease.

After obtaining prior approval of the Institutional Review Board in our hospital, we studied ten people without a family history of IBD who acted as controls, and nine first-degree relatives of patients with Crohn’s disease, who did not exhibit signs or symptoms referrable to CD.

The control patients included four males and six females ranging in age from 40-82 years (mean-64.3). Each patient underwent a routine colonoscopy. (Olympus, Lake Success, NY) after appropriate consent. Table 1 shows further data regarding the group. These patients underwent colonoscopy for causes other than IBD such as screening, Guaiac positive stools, abdominal pain (Table 1).

| Clinical data | Control group | First degree relative |

| Number (n) | 10 | 9 |

| Mean age (Range) | 64.3 (40-82) | 50.1 (21-79) |

| Males | 4 | 2 |

| Females | 6 | 7 |

| Indications | ||

| Anemia | 1 | None |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | Pain/Weight loss (1) |

| Guaiac (+) | 3 | None |

| Surveillance | 5 | None |

| Study | 0 | 3 |

| IBS | 0 | 3 |

| Endoscopic findings | ||

| Normal | 5 | 6 |

| Hemorrhoids | 3 | 3 |

| Polyps | 2 | None |

| Family His of colitis | None | All |

| History of IBD | None | None |

Eleven first-degree relatives were initially studied but only nine were used in the final analysis. Two relatives were excluded as one had a prior history of radiation proctitis and the other had a prior sigmoid biopsy consistent with nons pecific inflammation. These relatives included two males and seven females ranging in age from 21-79 years (mean-50.1). Two relatives were from the same family (i.e. brother and sister of a CD patient). Otherwise, the relatives were unrelated to each other. After obtaining informed consent each underwent a flexible sigmoidoscopy (Olympus) upto splenic flexure without a prior bowel prep. (Refer to Table 1). There was one patient in this group with abdominal pain and weight loss who was diagnosed with depression and anxiety but no pathologic condition was found. Also, as shown in the table, endoscopic findings were of minimal significance in both groups.

Demographic data of the eight CD patients (the index cases of the first-degree relatives) were analyzed and compared (Table 2).

| Clinical data | Number |

| Mean age | 44 (26.93) |

| Males | 2 |

| Females | 6 |

| Extent of the disease | |

| Ileum and colon | 5 |

| Ileum alone | 2 |

| Colon alon | 1 |

| Duration of the disease | |

| <10yrs | 1 |

| 10-30yrs | 6 |

| >30yrs | 1 |

| Present medications | |

| 6MP, steroids, ASA | 4 |

| ASA, steroids | 2 |

| ASA | 1 |

| None | 1 |

| History of Surgery | |

| Yes | 6 |

| No | 2 |

| Number of first degree relatives | |

| One relative | 7 |

| Two relatives | 1 |

Three mucosal biopsies were obtained from the sigmoid or descending colon in each patient in both groups. The biopsy samples, weighing between 15 mg and 30 mg each, were immediately wrapped in aluminum foil, placed in a container of liquid nitrogen and stored at -70 °C entigrade until they were processed. Tissue was crushed and homogenized in diluent from IL-kits (Quantikine, R & D systems) for 30 seconds, then centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 r/min. The supernatant fluid was used for assaying interlukins. Histologic evaluation was only performed if endoscopic abnormalities were noted as it would have, otherwise, delayed the procedure.

A solid phase ELISA using Quantikine kits (Research and Diagnostic Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to measure IL-1B, IL-2, IL-6, and IL-8. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM. The Quantikine method had a sensitivity of 0.03 pg-0.08 pg and a standard curve linearity of 0.03 pg to 3.0 pg. A Student’s independent test was used to compare data from the two groups and P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

The concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, and IL-8 were significantly (P < 0.05 ) higher in the colonic mucosa of first-degree relatives ( 3.40 ng/g ± 0.56 ng/g, 1.19 ng/g ± 0.21 ng/g, 11.98 ng/g ± 2.62 ng/g, respectively, Figure 1 ) when compared to controls ( 1.86 ng/g ± 0.30 ng/g, 0.69 ng/g ± 0.01 ng/g, 5.41 ng/g ± 1.87 ng/g, respectively). No significant difference was found in the concentration of IL 1B between relatives (0.85 ng/g ± 0.17 ng/g) and controls (1.03 ng/g ± 0.15 ng/g).

Individually, seven of the nine relatives had significantly higher levels of IL-2 and IL-6 and six relatives had significantly higher IL-8 levels than the mean value of controls. Interestingly, mean IL-1B and IL-6 levels of the two relatives from the same family (0.23 ng/g ± 0.09 ng/g and 0.21 ng/g ± 0.09 ng/g, respectively) were significantly lower (P < 0.05) than that of the other relatives (1.03 ng/g ± 0.16 ng/g and 1.47 ng/g ± 0.14 ng/g, respectively).

We also compared various subsets of the CD index cases to see if there were any differences in the corresponding first-degree relative cytokine levels (Table 2). In analyzing age, severity, duration or extent of disease, medications, and history of surgery, there were no significant differences between the subsets of the relative group in any category.

There is evidence that inflammatory bowel disease is determined by genetic predisposition. Supporting data include familial aggregation[6,15] and an increased concordance rate in monozygotic twins compared with dizygotic twins[16]. CD patients have a more frequent positive family history than ulcerative colitis (UC) patients[17]. Relatives of CD patients have a higher risk of IBD than those of UC patients[18,19]. There is also a higher concordance rate for CD than for UC among either monozygotic or dizygotic twins[16]. This suggests that hereditary predisposition may play a more important role in CD than UC.

Genetic studies have used subclinical markers in unaffected family members of IBD to either indicate the genetic abnormality predisposing to a disease or identify those in whom a subclinical phase of the disease process is occurring. These include serum antibodies (i.e. ANCA[20,21], antibodies to viruses, bacteria, mycoplasma, food antigens[22], and colonic epithelial cells [23]), colonic mucin abnormalities[24], obligate anaerobic fecal flora[25], mucosal production of IgG subclasses[26], and C3 dysfunction[27]. Abnormal elevations of these markers have been seen in healthy relatives of either CD or UC patients or both.

Most studies on relatives of CD patients have analyzed intestinal permeability in patients with CD and their first-degree relatives by measuring urinary excretion of poorly absorbed, water-soluble compounds such as polyethylene glycol (PE G-400) and large sugars, including lactulose, mannitol, and rhamnose[28] , 51 Cr-labelled ethylene diaminetetr-aacetic acid ( EDTA )[29] and luminal prostaglandin[30] and hyaluronin[31] release. Although initial studies have shown increased permeability in patients with CD[29,32-34] and their first-degree relatives[35,36], several additional studies[37-39] have been inconsistent, showing no increased permeability in either group.

Hollander[40] and May et al[41] in 1993, reviewed earlier studies and found that most studies showed a significant increase in permeability in 10% of first-degree asymptomatic relatives as it is possible that only a subgroup of relatives of CD patients are genetically susceptible. A recent study[42] has confirmed this by showing that the subset of asymptomatic relatives with increased intestinal permeability had increased CD45 (common leukocyte a ntigen) isoform in peripheral blood cells similar to CD patients. These findings suggest that the permeability defect in CD patients may serve as a subclinical and genetic marker for CD and is not secondary to intestinal inflammation[34] or may indicate early intestinal damage (preclinical expression).

Our study is the first to our knowledge to determine cytokine levels, known to be elevated in the colonic mucosa of CD patients and in asymptomatic relatives of CD patients. The fact that IL-2, IL-6, and IL-8 were significantly elevated suggests a possibility of early intestinal damage in the relatives gorup similar to the studies of increased permeability in these patients. Although the number of cases were small (n = 9), six of the nine patients had significant elevations of all three cytokines (IL = 2, IL-6, and IL-8) versus controls (the others had significant elevations of at least one or two of these cytokines). Whether a subset of these relatives are actually more predisposed to the disease than controls, as suggested in the permeability studies, has yet to be known. It is also of interest that we could not find any significant differences in cytokine levels between subsets of the relatives with regard to the various parameters of the in dex CD patients (listed in Table 2). The fact that the two relatives from the same family had significantly lower levels than the rest of the group is of questi onable value. Future studies including more patients and the evaluation of other cytokines would be of interest and would help in determining the significance of these alterations in this group.

This study shows that asymptomatic relatives of CD patients have increased levels of cytokines in normal-looking colonic mucosa. Studies with intestinal permea bility have been inconsistent. It may be possible that increased cytokines are an early event in the pathogenesis of the disease. Whether these increased cytoki nes lead to increased permeability and than to CD is something that needs further investigation.

Edited by You DY

| 1. | Sartor RB. Cytokines in intestinal inflammation: pathophysiological and clinical considerations. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:533-539. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Weissman S, Lam S, Bailey B, Sachdeva C, Greenberg R, Blumstein M. Cytokine levels in first-degree relatives of patients with in-flammatory bowel disease (IBD) and in patients with IBD or other colitides (abstract). Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1700. |

| 3. | Lam S, Weissman S, Bailey B, Bank S. Elevated basal intestinal mucosal cytokine levels in first degree relative of patients with Crohn's disease (abstract). Gastroenterology. 1995;108:A856. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Weissman S, Lam S, Bailey B, Greenberg R, Blumstein M, Bank S. Can intestinal mucosal cytokine levels be used as markers to dif-ferentiate and assess the severity of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease patients (abstract). Gastroenterology. 1995;108:A939. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Lam S, Weissman S, Bailey B, Bank S, Greenberg R, Blumstein M. Enhanced mucosal cytokine production in radiation proctitis (abstract). Gastroenterology. 1995;108:A856. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Orholm M, Munkholm P, Langholz E, Nielsen OH, Sørensen TI, Binder V. Familial occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:84-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 462] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McConnell RB. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. In: Allan RB, Keighley MR, Alexander-Williams J, Hawkins C, eds. Inflam-matory Bowel Diseases. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. 1983;8-16. |

| 8. | Rotter JI. Immunogenetic susceptibilities in inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1990;4:261-266. |

| 9. | Rotter JI, Shohat T, Vadheim CM. Is IBD a genetic disease. In: Rachmelowitz D, Zimmerman J, eds. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1990;5-18. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Yang H, Shohat T, Rotter JI. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. In: Macdermott RP, Stenson WF, eds.Inflammatory Bowel Disease. New York: Elsevier. 1992;17-51. |

| 11. | Hollander D, Vadheim CM, Brettholz E, Petersen GM, Delahunty T, Rotter JI. Increased intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and their relatives. A possible etiologic factor. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:883-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Katz KD, Hollander D, Vadheim CM, McElree C, Delahunty T, Dadufalza VD, Krugliak P, Rotter JI. Intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and their healthy relatives. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:927-931. [PubMed] |

| 13. | May GR, Sutherland LR, Meddings JB. Lactulose/Mannitol per-meability is increased in relatives of patients with Crohn's disease (abstract). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:A394. |

| 14. | Pironi L, Miglioli M, Ruggeri E, Dallsata MA, Ornigotti L, Valpiani D, Barbara L. Effect of non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAID) on intestinal permeability in first degree relatives of patients with Crohn's disease (abstract). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:A679. |

| 15. | Roth MP, Petersen GM, McElree C, Vadheim CM, Panish JF, Rotter JI. Familial empiric risk estimates of inflammatory bowel disease in Ashkenazi Jews. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1016-1020. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Tysk C, Lindberg E, Järnerot G, Flodérus-Myrhed B. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in an unselected population of monozygotic and dizygotic twins. A study of heritability and the influence of smoking. Gut. 1988;29:990-996. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Farmer RG, Michener WM, Mortimer EA. Studies of family history among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol. 1980;9:271-277. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Monsén U, Bernell O, Johansson C, Hellers G. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among relatives of patients with Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:302-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang H, McElree C, Roth MP, Shanahan F, Targan SR, Rotter JI. Familial empirical risks for inflammatory bowel disease: differences between Jews and non-Jews. Gut. 1993;34:517-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shanahan F, Duerr RH, Rotter JI, Yang H, Sutherland LR, McElree C, Landers CJ, Targan SR. Neutrophil autoantibodies in ulcerative colitis: familial aggregation and genetic heterogeneity. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:456-461. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lee JC, Lennard-Jones JE, Cambridge G. Antineutrophil antibodies in familial inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:428-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Elson CO. The immunology of inflammatory bowel disease. In: Kirsner JB,Shorter RG, eds. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. 1988;97-164. |

| 23. | Fiocchi C, Roche JK, Michener WM. High prevalence of antibodies to intestinal epithelial antigens in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and their relatives. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:786-794. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Tysk C, Riedesel H, Lindberg E, Panzini B, Podolsky D, Järnerot G. Colonic glycoproteins in monozygotic twins with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:419-423. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Van de Merwe JP, Schröder AM, Wensinck F, Hazenberg MP. The obligate anaerobic faecal flora of patients with Crohn's disease and their first-degree relatives. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:1125-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Helgeland L, Tysk C, Järnerot G, Kett K, Lindberg E, Danielsson D, Andersen SN, Brandtzaeg P. IgG subclass distribution in serum and rectal mucosa of monozygotic twins with or without inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1992;33:1358-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Elmgreen J, Both H, Binder V. Familial occurrence of complement dysfunction in Crohn's disease: correlation with intestinal symptoms and hypercatabolism of complement. Gut. 1985;26:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hollander D. Crohn's disease--a permeability disorder of the tight junction. Gut. 1988;29:1621-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ainsworth M, Eriksen J, Rasmussen JW, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Intestinal permeability of 51Cr-labelled ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in patients with Crohn's disease and their healthy relatives. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:993-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ahrenstedt O, Hällgren R, Knutson L. Jejunal release of prostaglandin E2 in Crohn's disease: relation to disease activity and first-degree relatives. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;9:539-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ahrenstedt O, Knutson L, Hällgren R, Gerdin B. Increased luminal release of hyaluronan in uninvolved jejunum in active Crohn's disease but not in inactive disease or in relatives. Digestion. 1992;52:6-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ukabam SO, Clamp JR, Cooper BT. Abnormal small intestinal permeability to sugars in patients with Crohn's disease of the terminal ileum and colon. Digestion. 1983;27:70-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Olaison G, Leandersson P, Sjödahl R, Tagesson C. Intestinal permeability to polyethyleneglycol 600 in Crohn's disease. Peroperative determination in a defined segment of the small intestine. Gut. 1988;29:196-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hollander D. The intestinal permeability barrier. A hypothesis as to its regulation and involvement in Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:721-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hollander D, Vadheim CM, Brettholz E, Petersen GM, Delahunty T, Rotter JI. Increased intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and their relatives. A possible etiologic factor. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:883-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | May GR, Sutherland LR, Meddings JB. Lactulose/mannitol perme-ability is increased in relatives of patients with Crohn's disease (abstract). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:A697. |

| 37. | Teahon K, Smethurst P, Levi AJ, Menzies IS, Bjarnason I. Intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and their first degree relatives. Gut. 1992;33:320-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ruttenberg D, Young GO, Wright JP, Isaacs S. PEG-400 excretion in patients with Crohn's disease, their first-degree relatives, and healthy volunteers. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:705-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Munkholm P, Langholz E, Hollander D, Thornberg K, Orholm M, Katz KD, Binder V. Intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis and their first degree relatives. Gut. 1994;35:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hollander D. Permeability in Crohn's disease: altered barrier functions in healthy relatives. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1848-1851. [PubMed] |

| 41. | May GR, Sutherland LR, Meddings JB. Is small intestinal permeability really increased in relatives of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1627-1632. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Yacyshyn BR, Meddings JB. CD45RO expression on circulating CD19+ B cells in Crohn's disease correlates with intestinal permeability. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:132-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |