Published online Dec 15, 1999. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i6.477

Revised: September 20, 1999

Accepted: October 14, 1999

Published online: December 15, 1999

AIM: To examine the effect of irsogladine, a novel antiulcer drug, on the mucosal ulcerogenic response to monochloramine ( NH2Cl ) in rat stom ach, in comparison with rebamipide, another antiulcer drug with cytoprotective activity.

METHODS AND RESULTS: Oral administration of NH2Cl (120 mM) produced severe hemorrhagic lesions in unanesthetized rat stomachs. Both irso gladine (1 mg/kg-10 mg/kg, po) and rebamipide (30 mg/kg-100 mg/kg, po) dose-dependently prevented the development of these lesions in response to NH2Cl, the effect of irsogladine was significant at 3 mg/kg or greater, and that of rebamipide only at 100 mg/kg. The protective effect of irsogladine on NH2Cl-induced gastric lesions was significantly reduced by NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) but not by indomethacin, while that of rebamipide was significantly mitigated by indom ethacin but not by L-NAME. Topical application of NH2Cl (20mM) caused a marked reduction of potential difference (PD) in ex-vivo stomachs. This PD reduction was not affected by mucosal application of irsogladine, but significa ntly prevented by rebamipide. The mucosal exposure to NH4OH (120 mM) also caused a marked PD reduction in the ischemic stomach (bleeding from the carotid artery), resulting in gastric lesions. These ulcerogenic and PD responses caused by NH4OH plus ischemia were also significantly mitigated by rebamipide, in an indomethacin-sensitive manner, while irsogladine potently prevented such lesions without affecting the PD response, in a L-NAME-sensitive manner.

CONCLUSION: These results suggest that (1) NH2Cl generated either exogenously or endogenously damages the gastric mucosa, (2) both irsogladine and rebamipide protect the stomach against injury caused by NH2Cl, and (3) the mechanism underlying the protective action of irsogladine is partly mediated by endogenous nitric oxide, while that of rebamipide is in part mediated by endogenous prostaglandins.

- Citation: Yamamoto H, Umeda M, Mizoguchi H, Kato S, Takeuchi K. Protective effect of Irsogladine on monochloramine induced gastric mucosal lesions in rats: a comparative study with rebamipide. World J Gastroenterol 1999; 5(6): 477-482

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v5/i6/477.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v5.i6.477

Helicobacter pylori, recognized as the major cause of gastritis and peptic ulcer diseases[1-3]has a high activity of urease, resulting in a high concentration of amonia (NH4OH) in the stomach of infected patients[3]. Since H. pylori associated chronic active gastritis is characterized by an invasion of neutrophils in the gastric mucosa[1,2,4] and since neutrophils utilize the H2O2-myeloperoxidase-halide system to generate an oxidant capable of destroying a variety of mammalian cell targets as well as microorganis ms[5,6], it is assumed that neutrophil-derived hypochlorous acid (HClO) interacts with NH4OH to generate cytotoxic monochloramine (NH2Cl)[7,8]. Indeed, it has been shown that NH2Cl plays a role in the pathogenesis of NH4OH-induced gastric lesions in rats[9,10]. We have also reported previously that both endogenous and exogenous NH2Cl damaged the gastric mucosa at much lower concentrations than NH4OH[11,12].

Irsogladine, a novel antiulcer drug [ 2, 4-diamino- 6- ( 2, 5- dichlorophenyl )-s-triazine maleate], has been shown to not only prevent gastric mucosal lesions in a wide variety of experimental models but show the healing promoting action of gastric ulcers as well, without any suppression of gastric secretion[13-15]. These effects of irsogladine may be accounted for by cytoprotective activity, yet the detailed mechanism is not fully understood. Thus, it is of in terest to test whether this agent has any prophylactic action against NH2Cl-i nduced gastric lesions.

In the present study, we examined the effects of irsogladine on the mucosal ulcerogenic response induced by NH2Cl, either administered exogenously or occurring endogenously, and compared those with the effects of another cytoprotective drug, rebamipide. We also investigated the underlying mechanism of their protection, especially in relation to endogenous prostaglandins (PGs) and nitric oxide (NO).

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200 g-240 g in weight, Nippon Charles River , Shizuoka, Japan) were used in all experiments. The animals, kept in separate cages with raised mesh bottoms, were deprived of food but allowed free access to tap water for 18 h prior to the experiments. Studies were carried out using four to eight rats under either conscious or anesthetized conditions induced by urethane (1.25 g/kg, ip). All experimental procedures described here were approved by the Experimental Animal Research Committee of the Kyoto Pharmaceutical University.

The experiments were classified into roughly two studies: one was to investigate the effects of irsogladine and rebamipide on gastric ulcerogenic response to exogenously administered NH2Cl in unanesthetized rats, and the other was to investigate their effects on gastric ulcerogenic response to NH4OH in anesthetized rats subjected to ischemia. In the latter situation, it is assumed that NH2Cl is generated endogenously from interaction of NH4OH with neutrophil-derived HClO[10].

The effects of irsogladine and rebamipide on gastric mucosal ulcerogenic response induced by exogenous NH2Cl. The animals were administered 1 ml of NH2Cl (120 mM)-po by esophageal intubation. The solution of NH2Cl was prepared by mixing NH4OH (240 mM) and HClO (240 mM) in a test tube, immediately before the administration. The animals were sacrificed 1 h after the admi nistration of NH2Cl, and the stomachs were removed, inflated by injecting 8 mL of 2% formalin and immersed in 2% formalin for 10 min to fix the gastric wall, and opened along the greater curvature. The area (mm2) of hemorrhagic lesions was measured under a dissecting microscope with a square grid ( × 10). The person measuring the lesions did not know the treatment given to the animals. These procedures were used in all the subsequent studies for evaluating macroscopical lesions. Irsogladine ( 1, 3 and 10 mg/kg ) and rebamipide ( 30 and 100 mg/kg ) were administered po 30 min before NH2Cl treatment. In some cases, indomethacin (10 mg/kg, sc) or L-NAME ( 10 mg/kg, iv ) was given 60 min or 40 min before NH2Cl treatment.

Transmucosal potential difference ( PD ) was measured in chambered stomachs of anesthetized rats as previously described[15]. Briefly, a rat stomach was mounted on an ex-vivo chamber (area exposed 3.14 cm2) and perfused at a flow rate of 1mL/min with saline (154 mM-NaCl). PD was determined using two agar bridges, one positioned in the chamber and the other in the abdominal cavity, and monitored continuously on a recorder (U-228, Tokai-Irika, Tokyo, Japan ). Approximately 1h after PD was stabilized, the perfusion system was interupted and the solution in the chamber was withdrawn, and the mucosa was exposed to 1 mL carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) solution (control group), 20 min later followed by 1 mL NH2Cl (20 mM, the final concentration is 10 mM) for 10 min. After application of NH2Cl, the mucosa was rinsed with saline, another 2 mL saline was instilled, and the perfusion system was resumed. Irsogladine ( 3 mg/kg ) or rebamipide (100 mg/kg) was app lied to the chamber for 30 min in place of CMC solution, starting 20 min before NH2Cl treatment. In a separate experiment, the animals were subjected to ischemia by bleeding from the carotid artery ( 1 mL/100 g body weight ), then the mucosa was exposed to 1 mL of CMC, 20 min later followed by 1 mL of NH4OH (120 mM, the final concentration is 60 mM ) for 1 h. At the end of the experiment, the mucosa was excised, and the area ( mm2 ) of hemorrhagic lesions was measured as described as above. Irsogladine (3 mg/kg ) or rebamipide (100 mg/kg) was applied to the chamber 10min before the onset of ischemia plus NH4OH treatment. Control animals received CMC as the vehicle. In some cases, indomethacin (10 mg/kg) was given sc 30 min before rebamipide, while L-NAME ( 10 mg/kg ) was given iv 10 min before irsogladine treatment.

Drugs used in this study were urethane (Tokyo Kasei, Tokyo, Japan ), irsogladine ( Nihon-Shinyaku Co., Kyoto, Japan), rebamipide (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Toku shima, Japan ), indomethacin and L-NAME (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA). I ndomethacin was suspended in saline with a drop of Tween 80 (Wako, Osaka, Japan), while L-NAME was dissolved in saline. Other drugs were suspended with 0.5% CMC solution. Each drug was prepared immediately before use and administered poorsc in a volume of 0.5 mL/100 g body weight or iv in a volume of 0.1 mL/100 g body weight or applied topically to the chamber in a volume of 1 mL/stomach.

Data are presented as the means ± SE from 4 to 8 rats per group. Statistically analyses were performed using two-tailed Student’s t test or Dunnett’s mult iple comparison test, and P < 0.05 values were regarded as significant.

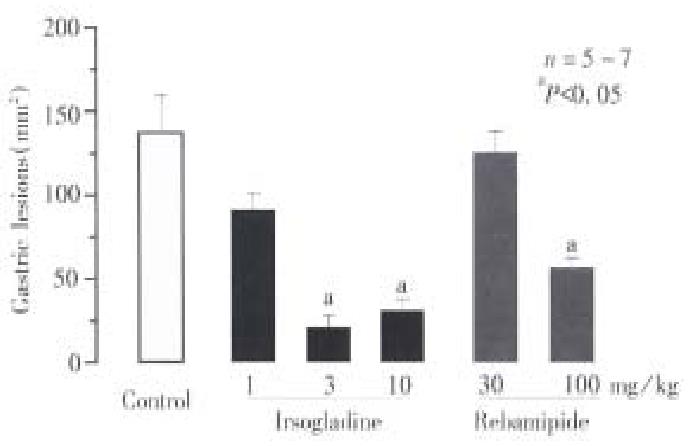

Intragastric administration of NH2Cl caused severe band-like hemorrhagic lesi ons in the gastric mucosa, the lesion score being 138.0 mm2± 19.0 mm2. Pretreatment of the animals with irsogladine (1, 3 and 10 mg/kg, po) significantly reduced the severity of gastric lesions in response to NH2Cl in a dose-dependent manner. The degree of inhibition was 35.1%, 86.3% and 83.3%, respectively (Figure 1 ). Rebamipide ( 30 and 100 mg/kg, po ) also lowered the severity of gastric lesions induced by NH2Cl, but the degree of inhibition at 100 mg/kg was 59.3%, which was less than that obser ved by irsogladine at 3 mg/kg.

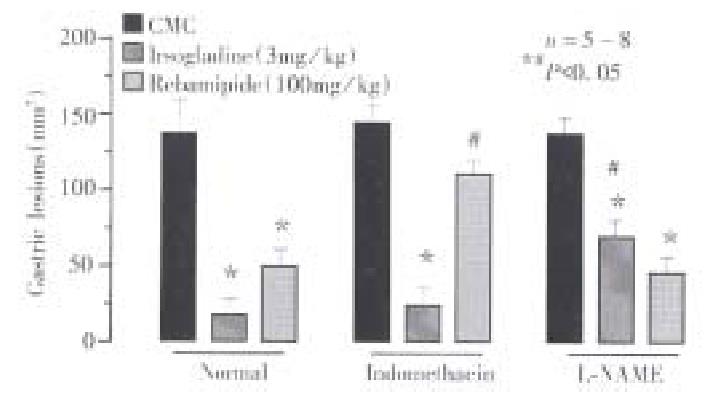

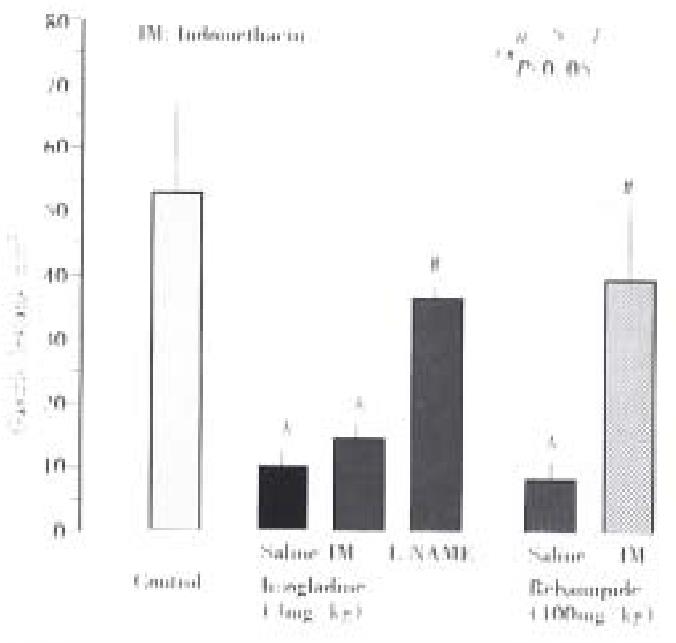

The severity of gastric lesions induced by NH2Cl was not affected by prior administration of either indomethacin (5 mg/kg, sc) or L-NAME (10 mg/kg, iv), the lesion score being 146.8 mm2± 9.8 mm2 or 135.6 mm2± 7.0 mm2, respectively (Figure 2). However, the pro tective action of irsogladine (3 mg/kg, po) against NH2Cl-induced gastric lesions was significantly mitigated by prior administration of L-NAME but not indomethacin; the lesion score in the presence of L-NAME was 72.8 mm2± 9.1 mm2, which was significantly greater than that observed in the absence of L-NAME (19.8 mm2± 3.1 mm2). By contrast, indomet hacin but not L-NAME significantly antagonized the protective action of rebamip ide (100 mg/kg, po) against these lesions.

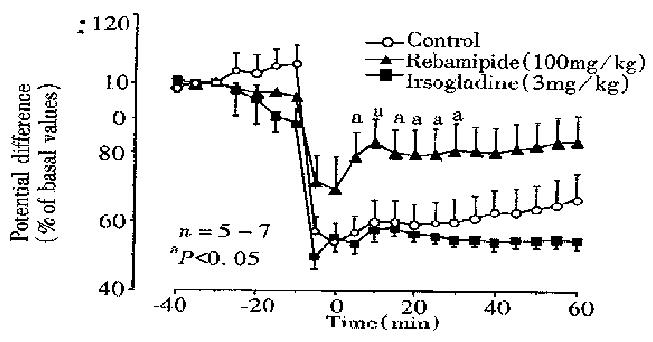

Normal stomachs mounted on the chamber and perfused with saline generate d a stable PD of -30 to -38 mV ( mucosa negative ), and the values remained relatively unchanged during a 2-h test period. Mucosal exposure to NH2Cl (10 mM) caused a marked reduction of PD to 60.0% ± 6.2% of basal values within 10 min, and the PD remained low for 1 h thereafter (Figure 3). The PD reduction in response to NH2Cl was not affected by prior exposure of the mucosa to irso gladine (3 mg/kg). However, the reduced PD response to NH2Cl was signif icantly mitigated when the mucosa was pre-exposed to rebamipide (100 mg/kg) for 30 min; the PD reduced to 57.7% ± 3.1% of basal values 10 min later, which was significantly less as compared with that ( 60.0% ± 6.2% of basal values ) in control rats.

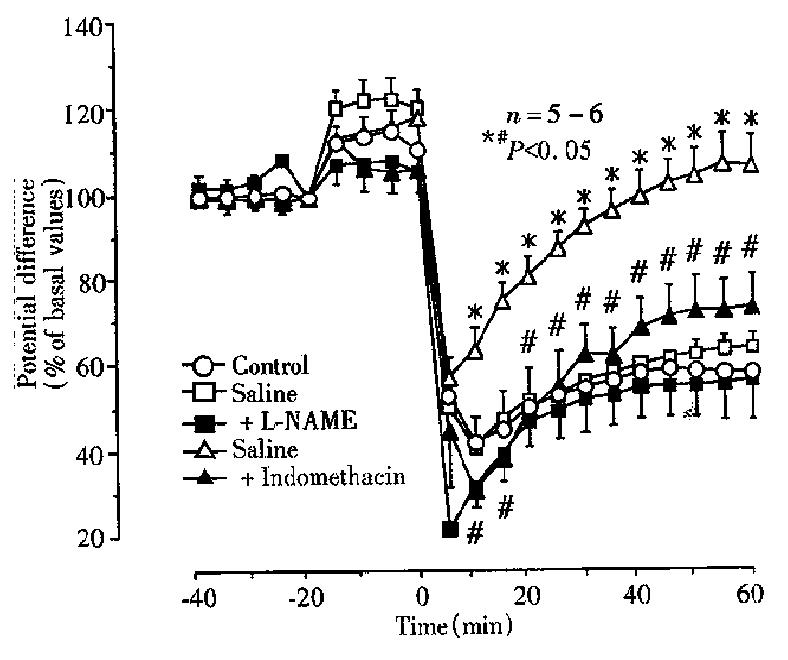

To confirm the protective action of irsogladine and rebamipide on NH2Cl-induc ed gastric toxicity, we tested the effects of these drugs on the mucosal ulcerogenic and PD responses induced by endogenously generated NH2Cl by application of a low concentration of NH4OH (60 mM) in the ischemic stomach[9]. As shown in Figure 4, topical application of NH4OH at 60 mM produced a persistent reduction of PD in the stomach made ischemic by bleeding; the PD was reduced to 42.6% ± 6.2% of basal values within 10min and remained low thereafter. This conc entration of NH4OH did not have any effect on PD in normal stomachs without subjecting to ischemia (not shown). The reduced PD response to NH4OH plus ischemia was not affected by prior exposure of the mucosa to irsogladine ( 3 mg/kg ), in the absence or presence of L-NAME. By contrast, rebamipide ( 100 mg/kg )-pre-exposed to the mucosa significantly attenuated the PD reduction in response to NH4OH plus ischemia. In these animals the recovery of PD was also significantly expedited, and the PD almost completely normalized within 60 min after NH4OH plus ischemia. In addition, the preventive effect of rebamipide on the PD response to NH4OH plus ischemia was also significantly antagonized in the presence of indomethacin.

On the other hand, the mucosal exposure to NH4OH in the ischemic stomachs resulted in severe hemorrhagic lesions within 1 h, the lesion score being 53.6 mm2± 12.2 mm2 ( Figure 5). The development of gastric lesions induced by NH4OH plus ischemia was significantly prevented by irsogladine ( 3 mg/kg ) as well as rebamipide (100 mg/kg ), the inhibition being 79.5% and 82.3%, respectively. The protective effect of irsogladine or rebamipide against NH4OH plus ischemia-induced gastric lesions was significantly antagonized by L-NAME or indomethacin, respectively.

The present study demonstrated that irsogladine, a novel antiulcer drug, conferred a protection against gastric damage induced in rat stomachs by NH2Cl, either given exogenously or occurred endogenously. We also found that rebamipide, another antiulcer drug, showed similar protection against such damage, although the effect was less potent than that of irsogladine. In addition, the present results suggest that the mechanisms underlying their protection are different; the protective action of irsogladine is partly mediated by endogenous NO, while that of rebamipide is accounted for by endogenous PGs as well as a radical scavenging action.

H. pylori has a high urease enzyme activity, resulting in an abnormally high concentration of ammonia (NH4OH) in the stomach of infected patients[3]. It is also known that NH4OH interacts with neutrophil-derived HClO to gen erate cytotoxic NH2Cl, a powerful oxidant capable of destroying a variety of micro-organisms as well as mammalian cell targets[4-7]. Murakami et al[17] demonstrated in rats that NH4OH-induced gastric mucosal lesions were significantly inhibited by taurine, a scavenger of HClO, suggesting a pathogenic role of NH2Cl in the development of such lesions. We also found previously that the mixture of low concentration of NH4OH and HClO, which did not have any gastric mucosal toxicity by each alone, caused severe lesions in the rat gastric mucosa under unanesthetized conditions[11,12]. In addition, we reported that the gastric lesions induced by endogenously generated NH2Cl by a low concentration of NH4OH plus ischemia were totally prevented by taurine in anesthetized ex-vivo stomachs[11,12]. It is known that ischemia activates xanthine oxidase, which is responsible for the production of reactive oxygen metabolites such as H2O2, and that the generation of HClO by neutrophils is dependent on the quantity of H2O2 produced[4,5]. It may therefore be assumed that NH4OH even at low concentrations produces NH2Cl by intera ction with HClO in the ischemic stomach, resulting in damage to the mucosa.

The gastric lesions induced by oral administration of NH2Cl were significantly prevented by irsogladine as well as rebamipide in a dose-dependent manner, although the effect of irsogladine was more potent than that of rebamipide. Similar results were obtained by these drugs against gastric lesions induced by NH4OH plus ischemia, where NH2Cl is assumed to be generated endogenously from inter action of NH4OH with neutrophil-derived HClO[10]. These results clearly showed that both irsogladine and rebamipide conferred a protection against damage induced by NH2Cl, either administered exogenously or occurring endogenously. However, the mechanisms underlying gastric protection seemed to be different between these two drugs. The protective action of irsogladine was significantly attenuated by pretreatment with L-NAME but not indomethacin, while that of rebamipide was attenuated by indomethacin but not L-NAME. These results suggest that the protective action of irsogladine and rebamipide may be mediated by endogenous NO and PGs, respectively. Moreover, these drugs caused different effects on the PD response induced by NH2Cl or NH4OH plus ischemia. Rebamipide signifi cantly prevented the PD reduction in response to these treatments while irsogladine had no effect on such PD responses. It is considered that gastric PD is one of the indicators for the integrity of the gastric mucosa, including the develop ment of mucosal injury as well as the recovery from injury[18,19]. From the present results, it is suggested that irsogladine does not inhibit the onset of injury caused by NH2Cl but prevents the ultimate generation of gastric damage, probably by preventing the later extension of injury, while rebamipide redu ced the gastric ulcerogenic response by inhibiting the initial irritating action of NH2Cl on the mucosa.

The local release of NO regulates the gastric mucosal microcirculation and maintains the mucosal integrity in collaboration with PGs and sensory neurons[20,21]. At present, the mechanism by which irsogladine stimulates the release of NO in the gastric mucosa remains unknown. We previously reported that mucosal application of NO donor prevented the development of gastric lesions induced by NH2Cl without any influence on the PD responses[11,12]. These data are in agreement with the present findings that irsoglandine reduced the severity of NH2Cl-induced gastric lesions but had no effect on the reduced PD response. On the other hand, it has been shown that rebamipide protects the gastric mucos a from various necrotizing agents by increasing PG biosynthesis in the mucosa and scavenging free redicals[22-24]. Exogenous PGE2 has also been shown to inhibit gastric lesions in response to NH2Cl or NH4OH plus ischemia[11]. These data support the present observation that rebamipide protected the stomach against NH2Cl-induced damage, in an indomethacin-sensitive manner. It should also be noted in the present study that rebamipide prevented the PD reduction in response to NH2Cl or NH4OH plus ischemia. Since taurine, a scavenger of HClO, markedly suppressed the PD reduction caused by NH2Cl[11,12], it is likely that rebamipide may prevent gastric ulcerogenic and PD responses to NH2Cl through a radical scavenging action, in addition to mediation by endogenous PGs.

In conclusion, the present results taken together suggest that NH2Cl generated either endogenously or exogenously, damages the gastric mucosa at a low concentration. Gastric mucosal lesions caused by NH2Cl was prevented by both irsogladine and rebamipide, although the former action was more potent than the latter. Although the exact mechanisms underlying gastroprotection afforded by irsogladine and rebamipide remain unknown, it is assumed that their mechanisms are different; the effect of irsogladine is mediated at least partly by endogenous NO, while that of rebamipide is attributable to endogenous PGs as well as its radical scavenging action. Since an important feature of H. pylori infection is neutrophil infiltration in the gastric mucosa[1,2], it is possible that NH2Cl is formed in the inflammed gastric mucosa, where neutrophil and H. pylori are located in juxtaposition. Thus, the present study also suggests that irsogladine may have therapeutic potential in the prevention and/or treatment of gastric mucosal damage related to H. pylori.

This work was supported in part by a grant from Nippon Shinyaku Co. Ltd.

Edited by Jing-Yun Ma

Proofread by Qi-Hong Miao

| 1. | Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1:1273-1275. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Graham DY. Campylobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:615-625. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Marshall BJ, Langton SR. Urea hydrolysis in patients with Campylobacter pyloridis infection. Lancet. 1986;1:965-966. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Whitehead R, Truelove SC, Gear MW. The histological diagnosis of chronic gastritis in fibreoptic gastroscope biopsy specimens. J Clin Pathol. 1972;25:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Badwey JA, Karnovsky ML. Active oxygen species and the functions of phagocytic leukocytes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:695-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 854] [Cited by in RCA: 812] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Klebanoff SJ. Oxygen metabolism and the toxic properties of phagocytes. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:480-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Grisham MB, Jefferson MM, Melton DF, Thomas EL. Chlorination of endogenous amines by isolated neutrophils. Ammonia-dependent bactericidal, cytotoxic, and cytolytic activities of the chloramines. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10404-10413. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Grisham MB, Hernandez LA, Granger DN. Xanthine oxidase and neutrophil infiltration in intestinal ischemia. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:G567-G574. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Murakami M, Asagoe K, Dekigai H, Kusaka S, Saita H, Kita T. Products of neutrophil metabolism increase ammonia-induced gastric mucosal damage. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:268-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dekigai H, Murakami M, Kita T. Mechanism of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric mucosal injury. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1332-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nishiwaki H, Kato S, Takeuchi K. Irritant action of monochloramine in rat stomachs: effects of zinc L-carnosine (polaprezinc). Gen Pharmacol. 1997;29:713-718. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kato S, Nishiwaki H, Konaka A, Takeuchi K. Mucosal ulcerogenic action of monochloramine in rat stomachs: effects of polaprezinc and sucralfate. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2156-2163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ueda F, Aratani S, Mimura K, Kimura K, Nomura A, Enomoto H. Effect of 2,4-diamino-6-(2,5-dichlorophenyl)-s-triazine maleate (MN-1695) on gastric ulcers and gastric secretion in experimental animals. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:474-477. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ueda F, Aratani S, Mimura K, Kimura K, Nomura A, Enomoto H. Effect of 2,4-diamino-6-(2,5-dichlorophenyl)-s-triazine maleate (MN-1695) on gastric mucosal damage induced by various necrotizing agents in rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:478-484. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Okabe S, Takeuchi K, Ishihara Y, Kunimi H. Effect of 2,4 diamino 6 (2,5 dichlorophenyl) s triazine maleate (MN-1695) on gastric secretion and on experimental gastric ulcers in rats. Pharmacometrics. 1984;24:683-689. |

| 16. | Takeuchi K, Ishihara Y, Okada M, Niida H, Okabe S. A continuous monitoring of mucosal integrity and secretory activity in rat stomach: a preparation using a lucite chamber. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1989;49:235-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Murakami M, Saita H, Teramura S, Dekigai H, Asagoe K, Kusaka S, Kita T. Gastric ammonia has a potent ulcerogenic action on the rat stomach. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1710-1715. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ivey KJ, DenBesten L, Clifton JA. Effect of bile salts on ionic movement across the human gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1970;59:683-690. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Svanes K, Ito S, Takeuchi K, Silen W. Restitution of the surface epithelium of the in vitro frog gastric mucosa after damage with hyperosmolar sodium chloride. Morphologic and physiologic characteristics. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:1409-1426. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Whittle BJ, Lopez-Belmonte J, Moncada S. Regulation of gastric mucosal integrity by endogenous nitric oxide: interactions with prostanoids and sensory neuropeptides in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;99:607-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tepperman BL, Whittle BJ. Endogenous nitric oxide and sensory neuropeptides interact in the modulation of the rat gastric microcirculation. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ishihara K, Komuro Y, Nishiyama N, Yamasaki K, Hotta K. Effect of rebamipide on mucus secretion by endogenous prostaglandin-independent mechanism in rat gastric mucosa. Arzneimittelforschung. 1992;42:1462-1466. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Yamasaki K, Kanbe T, Chijiwa T, Ishiyama H, Morita S. Gastric mucosal protection by OPC-12759, a novel antiulcer compound, in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;142:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yoshikawa T, Naito Y, Tanigawa T, Kondo M. Free radical scavenging activity of the novel anti-ulcer agent rebamipide studied by electron spin resonance. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43:363-366. [PubMed] |