Published online Feb 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i5.101280

Revised: November 11, 2024

Accepted: December 13, 2024

Published online: February 7, 2025

Processing time: 111 Days and 15.7 Hours

Gastrointestinal schwannomas (GIS) are rare neurogenic tumors arising from Schwann cells in the gastrointestinal tract. Studies on GIS are limited to small case reports or focus on specific tumor sites, underscoring the diagnostic and thera

To comprehensively examine the clinical features, pathological characteristics, treatment outcomes, associated comorbidities, and prognosis of GIS.

The study population included patients diagnosed with GIS at the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, between June 2007 and April 2024. Data were retrospectively collected and analyzed from medical records, including demographic characteristics, endoscopic and imaging findings, treatment modalities, pathological evaluations, and follow-up information.

In total, 229 patients with GIS were included, with a mean age of 56.00 years and a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.83. The mean tumor size was 2.75 cm, and most (76.9%) were located in the stomach. Additionally, 6.6% of the patients had other malig

Preoperative diagnosis of GIS via clinical characteristics, endoscopy, and imaging examinations remains challenging but crucial. Endoscopic therapy provides a minimally invasive and effective option for patients.

Core Tip: Gastrointestinal schwannomas (GIS) are rare neurogenic tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, posing considerable challenges in diagnosis and treatment. We retrospectively analyzed the clinical features, pathological characteristics, treatment outcomes, associated comorbidities, and prognosis of 229 patients diagnosed with GIS between June 2007 and April 2024. Our findings emphasize the critical role of endoscopy in improving diagnostic accuracy, guiding treatment strategies, and enhancing patient outcomes.

- Citation: Zhang PC, Wang SH, Li J, Wang JJ, Chen HT, Li AQ. Clinicopathological features and treatment of gastrointestinal schwannomas. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(5): 101280

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i5/101280.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i5.101280

Gastrointestinal schwannomas (GIS) are rare neurogenic tumors arising from Schwann cells in the gastrointestinal tract[1]. Representing only 2%-6% of all gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors, their detection is increasing with advances in endoscopic and imaging techniques[2]. Although GIS is generally benign[3], excision is typically reserved for symp

Due to the rarity of GIS, our understanding of this tumor type remains limited. Most studies are restricted to small case reports[5,6] or focus on specific tumor locations, including the stomach or esophagus[3,7], limiting our ability to fully comprehend the clinical presentation of GIS across the entire gastrointestinal tract.

The definitive diagnosis of GIS requires pathological and immunohistochemical examinations; however, as GIS lacks distinct clinical and imaging features, noninvasive preoperative diagnosis remains challenging. For example, imaging results from computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are often similar to those of GIST and other mesenchymal tumors, leading to a high rate of misdiagnosis[3]. Such misdiagnosis can cause unnecessary over

Our understanding of the optimal treatment approach for GIS is also limited, especially regarding the choice between endoscopic and surgical resection. Given that most GIS cases are benign, they can typically be effectively treated with minimally invasive endoscopic resection after accurate diagnosis[8]. However, these treatment methods are not fully standardized in clinical practice, and the prognostic differences between them remain unclear[9].

Therefore, this study aims to address these gaps by retrospectively analyzing clinical data from 229 patients with GIS, one of the largest sample sizes reported to date. By analyzing clinical features, pathological characteristics, treatment outcomes, and tumor-related comorbidities, we seek to deepen the understanding of GIS across diverse gastrointestinal sites. Additionally, this study aims to assess the current status of diagnosis and treatment, offering a scientific foundation for clinical decision-making and surgical approach selection, which may positively influence long-term patient outcomes.

This retrospective study analyzed clinical data from patients with GIS treated at The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, between June 2007 and April 2024. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the hospital before data collection.

In total, 229 patients who underwent surgical or endoscopic resection and were diagnosed with GIS based on postope

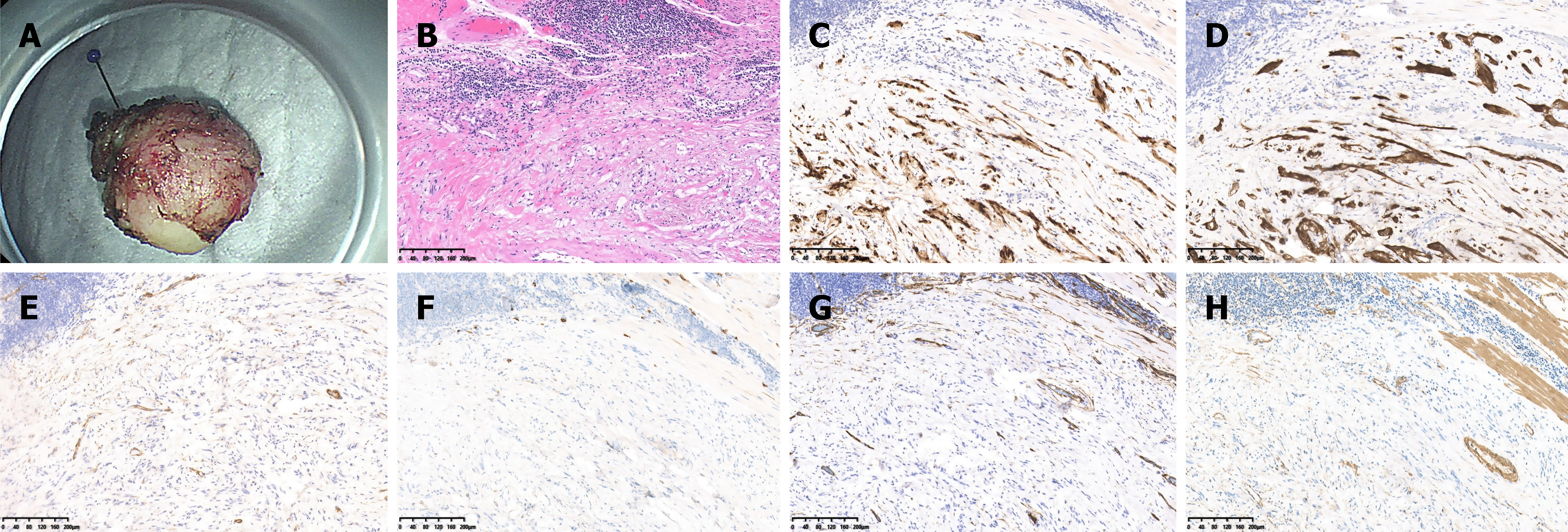

All tumors were examined and analyzed by at least two trained pathologists from the Pathology Department at the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Pathological sections of each tumor were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for routine histological evaluation. To further differentiate specific tumor types, immunohistochemical analysis was performed on selected samples, using markers such as S-100, SOX10, CD117, DOG-1, SMA, Desmin, Ki-67, SDHB, and HMB45. An expert gastrointestinal pathologist reviewed all histological samples to confirm schwannoma diagnoses. Figure 4 show representative images of GIS identification.

Seventy-seven patients were followed up via telephone for 5-30 months after resection to collect prognostic data, including recurrence, postoperative complications, and comorbidities.

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.3. Categorical and continuous variables were expressed as frequencies (percentages) and mean (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)], respectively. Comparisons between surgical and endoscopic resection groups were conducted using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the t-test or rank-sum test for continuous variables. All tests were two-sided, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

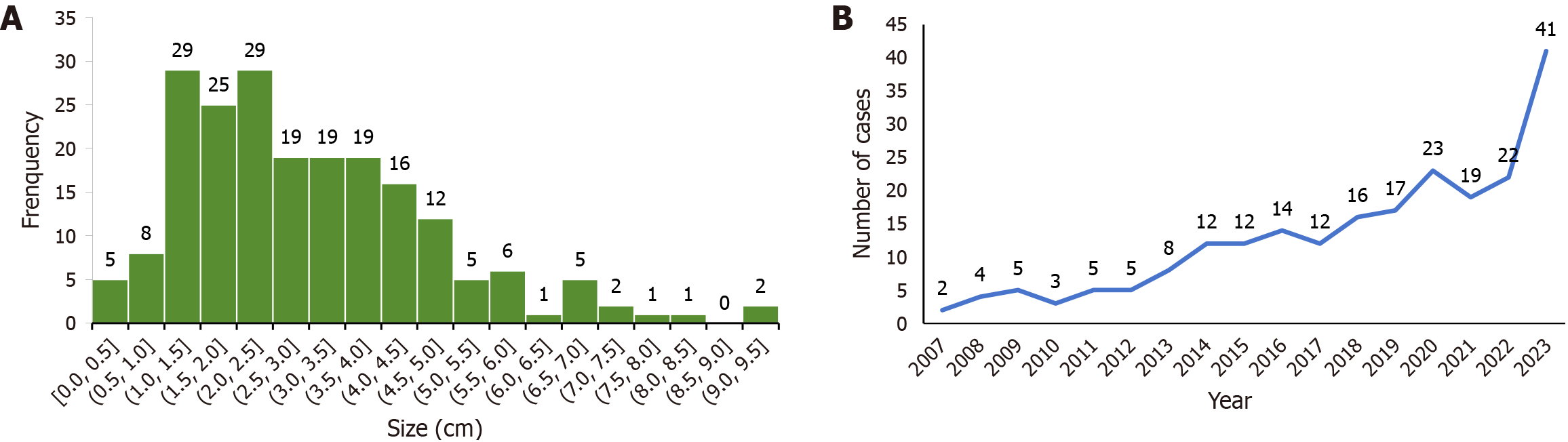

The study included patients aged 19-85 years, with a median age of 56.00 (48.00, 63.00) years, comprising 81 males (35.4%) and 148 females (64.6%). Tumor size was reported in 204 cases, with a mean size of 2.75 cm (1.80, 4.03) (range: 0.3-9.5 cm) (Figure 5A). The detection of GIS increased over time, from 32 cases between 2007 and 2013 to 114 cases between 2022 and 2024 (Figure 5B and Table 1). Regarding anatomical distribution, 176 (76.9%), 30 (13.1%), and 23 (10.0%) cases were located in the stomach, intestine, and esophagus, respectively. Detailed anatomical locations were also reported for some cases. Among the 176 GIS of the stomach, 3, 16, 94, 3, and 25 were located in the cardia, fundus, body, angle, and gastric antrum, respectively, while 35 did not report a specific location. Of the 30 intestinal GIS cases, 2, 20, and 8 cases were located in the duodenum, colon, and rectum, respectively (Table 1).

| Variable | Overall |

| Age, year, median (IQR) | 56.00 (48.00, 63.00) |

| Tumor size, cm, median (IQR) | 2.75 (1.80, 4.03) |

| Duration of follow-up, month, median (IQR) | 13.78 (5.53, 30.60) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 148 (64.6) |

| Male | 81 (35.4) |

| Year of diagnosis | |

| 2007-2013 | 32 (14.0) |

| 2014-2019 | 83 (36.2) |

| 2020-2024 | 114 (49.8) |

| Tumor location | |

| Esophagus | 23 (10.0) |

| Esophagus (unspecified site) | 3 (1.3) |

| Upper esophagus | 5 (2.2) |

| Middle esophagus | 6 (2.6) |

| Lower esophagus | 9 (3.9) |

| Stomach | 176 (76.9) |

| Stomach (unspecified site) | 35 (15.3) |

| Gastric cardia | 3 (1.3) |

| Gastric fundus | 16 (7.0) |

| Gastric body | 94 (41.0) |

| Gastric angle | 3 (1.3) |

| Gastric antrum | 25 (10.9) |

| Intestines | 30 (13.1) |

| Duodenum | 2 (0.9) |

| Ascending colon | 8 (3.5) |

| Transverse colon | 6 (2.6) |

| Descending colon | 3 (1.3) |

| Sigmoid colon | 3 (1.3) |

| Rectum | 8 (3.5) |

In this study, 29 patients with GIS had tumor comorbidities, with 15 patients experiencing malignant tumors. Of these, seven patients had other digestive tract tumors, including gastric stromal tumors, gastric adenocarcinoma, and colorectal adenoma. Additionally, four patients were diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma and three with renal clear cell carcinoma. Other malignancies included leukemia, lung adenocarcinoma, prostate adenocarcinoma, and thyroid cancer. Table 2 presents detailed comorbidities.

| Variable | Overall |

| Gastrointestinal neoplasms | |

| Esophageal leiomyoma | 1 (0.4) |

| Gastric stromal tumor | 1 (0.4) |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | 2 (0.9) |

| Colorectal adenoma | 2 (0.9) |

| Rectal adenocarcinoma | 1 (0.4) |

| Adenoma of the appendix | 1 (0.4) |

| Other tumors | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 4 (1.7) |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas | 1 (0.4) |

| Adrenal cortical adenoma | 1 (0.4) |

| Clear cell carcinoma of the kidney | 3 (1.3) |

| Hamartoma of kidney | 1 (0.4) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1 (0.4) |

| Leukemia | 1 (0.4) |

| Ovarian adenoma | 2 (0.9) |

| Adenocarcinoma of lung | 2 (0.9) |

| Meningioma | 1 (0.4) |

| Adenocarcinoma of prostate | 1 (0.4) |

| Breast cancer | 1 (0.4) |

| Thyroid cancer | 1 (0.4) |

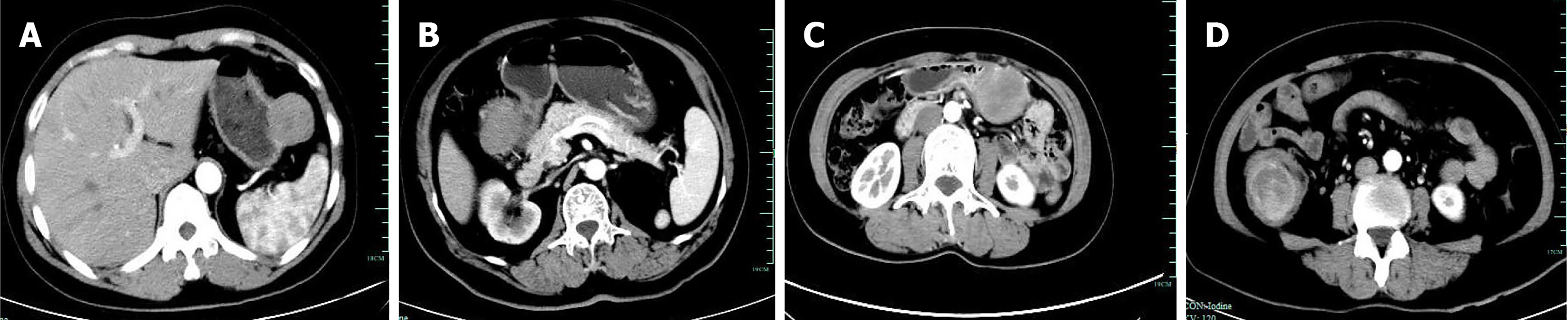

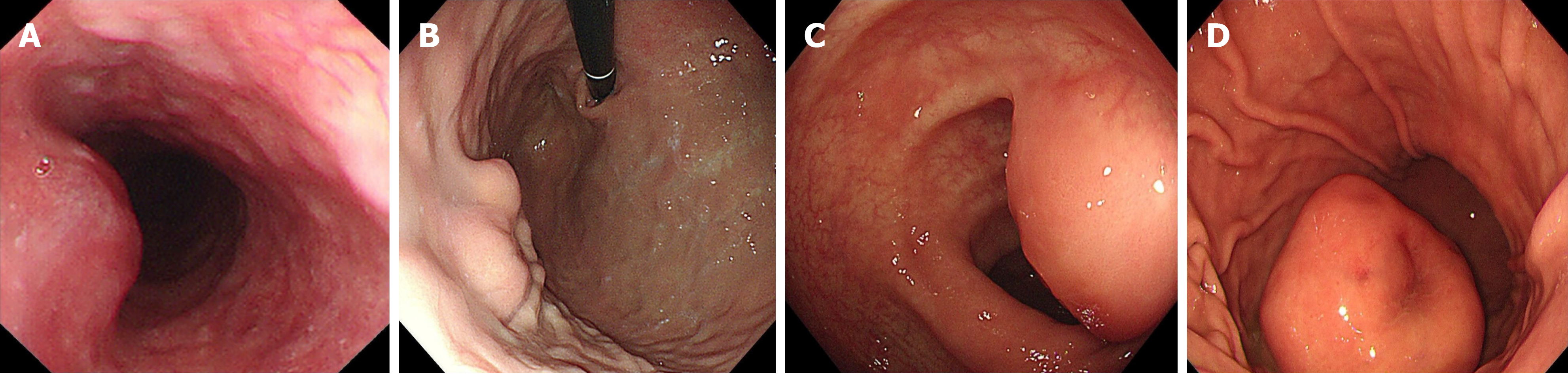

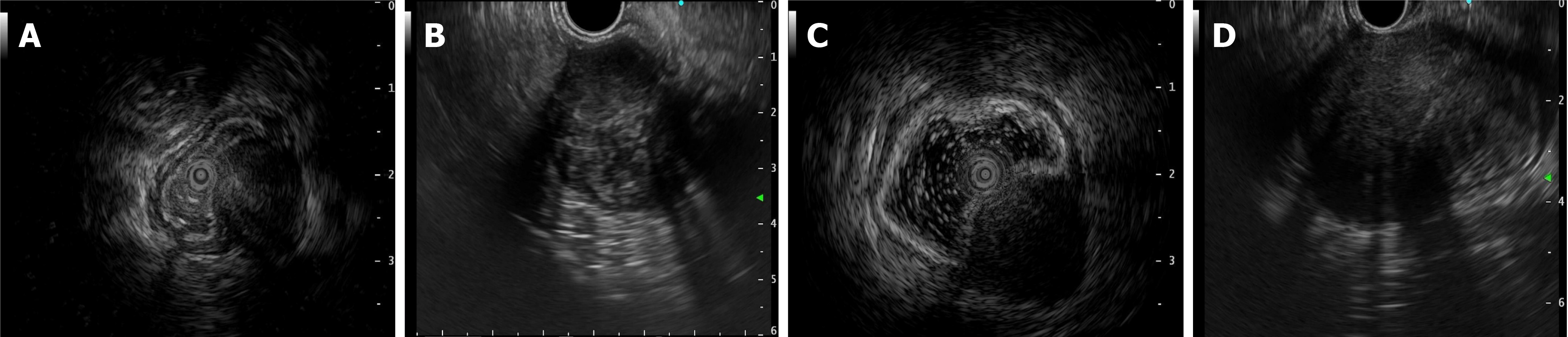

In the study of 229 patients, 168 underwent imaging examinations, including CT and MRI. In total, 179 patients underwent endoscopic examinations, including 84 patients who accepted additional EUS. The imaging findings predominantly indicated stromal tumors as the most common diagnosis, with many cases described as space-occupying lesions or masses. Only eight cases were suspected to be schwannomas by the radiologist. This pattern was also evident in endoscopic and clinical diagnoses. Most lesions observed on endoscopy were classified as “submucosal tumor” or “gastrointestinal stromal tumor,” with no suspicion of schwannoma in most cases. Of the 84 patients who were administered additional EUS, only five patients were preoperatively suspected of having schwannomas, and three of these were confirmed via EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and pathology. Schwannomas, unlike other submucosal tumors of the digestive tract, may present with enlarged lymph nodes around the tumor, although this was observed only in 11 out of 168 cases. Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the typical CT and endoscopic features, including EUS findings, of gastrointestinal tract schwannomas. Table 3 presents detailed information.

| Variable | Overall |

| Imaging diagnosis (n = 168) | |

| Space-occupying lesion/mass | 25 (14.9) |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 117 (69.6) |

| Leiomyoma | 8 (4.8) |

| Schwannoma | 8 (4.8) |

| Tumor | 9 (5.4) |

| No obvious abnormality | 1 (0.6) |

| Endoscopic diagnosis (n = 179) | |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 81 (45.2) |

| Submucosal tumor | 95 (53.1) |

| Space-occupying lesion/mass | 3 (1.7) |

| Endoscopic ultrasound diagnosis (n = 84) | |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 64 (76.2) |

| Leiomyoma | 8 (9.5) |

| Schwannoma | 5 (6.0) |

| Granular cell tumor | 2 (2.4) |

| Submucosal tumor | 5 (5.9) |

| Clinical diagnosis (n = 229) | |

| Space-occupying lesion/mass | 105 (45.9) |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 80 (34.9) |

| Leiomyoma | 3 (1.3) |

| Tumor | 37 (16.2) |

| Other diagnosis | 4 (1.7) |

| Treatment method (n = 214) | |

| Endoscopic surgery | 65 (30.4) |

| Endoscopic full-thickness resection | 33 (15.4) |

| Endoscopic submucosal dissection | 23 (10.7) |

| Submucosal tunnel endoscopic resection | 8 (3.7) |

| Snare polypectomy | 1 (0.5) |

| Surgery | 149 (69.6) |

Microscopic examination revealed that all tumor cells exhibited spindle-shaped morphology at the tumor center in every case (Figure 4). Chronic inflammatory cell infiltration was observed around the tumors, forming a lymphoid cuff in most cases-an important distinguishing feature from other mesenchymal tumors. Immunohistochemical analysis of 212 patients with GIS revealed that S100 (99.0%, 207/209) and SOX-10 (100%, 64/64) were generally positive. SDHB (100.0%, 46/46) also showed uniform positivity in all tested cases.

In contrast, CD117 (98.6%, 209/212), DOG-1 (98.9%, 179/181), and HMB45 (100%, 27/27) were predominantly negative, with only focal positivity observed in a few cases. Additionally, SMA (91.2%, 187/205) and Desmin (91.9%, 171/186) were also nearly negative. Ki-67 indices were below 10% in nearly all cases, with most falling below 5% (121/183). Table 4 shows detailed immunohistochemical results.

| Variable | Overall |

| S-100 (n = 209) | |

| + | 207 (99.0) |

| - | 2 (1.0) |

| SOX10 (n = 64) | |

| + | 64 (100.0) |

| CD117 (n = 212) | |

| - | 209 (98.6) |

| + (focal) | 3 (1.4) |

| DOG-1 (n = 181) | |

| - | 179 (98.9) |

| + (focal) | 2 (1.1) |

| SMA (n = 205) | |

| - | 187 (91.2) |

| + | 18 (8.8) |

| Desmin (n = 186) | |

| - | 171 (91.9) |

| + | 15 (8.1) |

| Ki-67 (n = 183) | |

| < 5% | 121 (66.1) |

| 5-10% | 61 (33.3) |

| > 10% | 1 (0.6) |

| SDHB (n = 46) | |

| + | 46 (100.0) |

| HMB45 (n = 27) | |

| - | 27 (100.0) |

In this study, 214 patients underwent endoscopic procedures, and 229 opted for surgical interventions. Among the endoscopic procedures, 33, 23, and 8 patients underwent endoscopic EFR, ESD, and STER, respectively, while only one patient underwent snare polypectomy (Table 3).

Patients undergoing endoscopic resection had smaller average tumor sizes than that of those treated with traditional surgery [1.60 (1.20, 2.50) cm vs 3.50 (2.30, 4.50) cm]. The proportion of patients selecting endoscopic treatment has significantly increased in recent years (P < 0.05). However, a statistically significant difference in sex distribution was observed (P = 0.045), possibly attributed to the predominance of female patients in the study sample, which may have amplified small sex differences in statistical analysis. No significant differences were found between the two groups regarding patient age (P = 0.155; Table 5). In total, 77 patients were followed for an average of 13.78 months (IQR: 5.53-30.60 months). Most patients experienced favorable outcomes, with no recurrence or postoperative complications. During follow-up, three patients developed other cancers: One patient was diagnosed with prostate cancer 1 year after surgery and esophageal cancer 8 years later; another developed esophageal and digestive system neuroendocrine carcinoma with liver metastasis 13 years post-surgery; and one patient was diagnosed with a luteinized right ovarian follicular membrane cell tumor 12 years after surgery.

| Variable | Endoscopic surgery (n = 65) | Surgery (n = 149) | P value |

| Age, year, median (IQR) | 53.00 (46.00, 62.00) | 57.00 (48.00, 64.00) | 0.155 |

| Tumor size, cm, median (IQR) | 1.60 (1.20, 2.50) | 3.50 (2.30, 4.50) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.045 | ||

| Female | 34 (52.3) | 101 (67.8) | |

| Male | 31 (47.7) | 48 (32.2) | |

| Tumor location | 0.047 | ||

| Intestines | 7 (10.8) | 23 (15.4) | |

| Esophagus | 12 (18.5) | 11 (7.4) | |

| Stomach | 46 (70.8) | 115 (77.2) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.002 | ||

| 2007-2013 | 3 (4.6) | 28 (18.8) | |

| 2014-2019 | 18 (27.7) | 56 (37.6) | |

| 2020-2024 | 44 (67.7) | 65 (43.6) |

In our retrospective analysis of 229 patients, which included more cases of GIS than that of most similar studies, we identified several clinicopathological features of this rare tumor. The detection rate of GIS has been rising in recent years, possibly due to the advancements in imaging technology, the widespread use of EUS-FNA, and increased clinician awareness. Additionally, the growth of screening programs and preventive endoscopy significantly contributes to the identification of GIS.

GIS is a rare gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumor, comprising approximately 2%-6% of all such tumors[2]. In our study, the stomach was the most common site (76.9%), followed by relatively lower prevalence rates in the intestines (13.1%) and esophagus (10.0%). The mean age of patients with GIS was 56 years, with a female predominance (male-to-female ratio of 1:1.83). Most patients (55.5%) fell within the 40-60 years age range, consistent with previous research findings[1].

GIS often coexists with other conditions, with a high comorbidity rate (6.6%), including certain malignant tumors. These findings underscore the significance of comprehensive tumor screening in clinical practice to detect or exclude potential comorbidities. Additionally, this association may provide insights into the pathogenesis of GIS, including the influence of shared genetic or environmental risk factors.

GIS are exceptionally rare tumors, and preoperative diagnosis remains highly challenging due to the nonspecific findings on CT and MRI[10,11] (misdiagnosis rates of 95.2% and 94.0%, respectively). The clinical symptoms, morphology, and growth patterns of GIS closely resemble those of the more common GIST, leading to diagnostic confusion[2,12]. Although researchers have investigated various methods to differentiate GIS from GIST-such as enhanced CT[13], multiparametric MRI, 18F-FDG PET[14], and endoscopic ultrasound[15]-the accuracy of preoperative diagnosis remains low. However, certain imaging features may aid in distinguishing GIS from GIST. GIS often presents with reactive enlarged lymph nodes around the tumor and may exhibit different features, including lesion margin, heterogeneous enhancement, necrosis, surface ulceration, and mixed growth[16-18]. Schwannomas and GISTs generally appear as hypoechoic submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer of the gastrointestinal tract, making through EUS challenging. EUS-FNA provides a minimally invasive method for obtaining tissue samples[19-21], which is essential for preoperative diagnosis. Accurate preoperative diagnosis is essential to avoid unnecessary extensive surgeries, particularly in anatomically complex regions such as the pancreas or the descending part of the duodenum, where surgical intervention can be more destructive[22,23]. Although nerve sheath tumors are generally benign, they still carry a risk of malignant transformation, necessitating regular follow-up and careful observation[10,24].

The gold standard for diagnosing GIS combines pathological evaluation with immunohistochemical analysis. Pathological features of GIS typically include spindle-shaped tumor cells, positive expression of S100 and/or SOX-10 proteins, and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration around the tumor[2]. In this study, the expression rates of S100 and SOX-10 were 99.0% and 100%, respectively, establishing them as critical biomarkers for GIS diagnosis[1,2,10]. Conversely, the expression of CD117, DOG-1, SMA, Desmin, and HMB45 was generally negative in GIS[1-3]. The focal positivity of CD117 and DOG-1 observed in two to three cases may be linked to residual Cajal cell proliferation. Similarly, the positive rates of SMA and Desmin are mostly associated with vascular and stromal components within the tumor.

Differentiating GIS from other mesenchymal tumors, including the more common GIST, requires a combination of immunohistochemical markers. For instance, GIST typically expresses CD117 and DOG-1 positively, while S-100 is negative[2]. Additionally, the Ki-67 index is another crucial marker for evaluating the malignant potential of GIS. A Ki-67 index above 10% is generally considered indicative of a higher malignancy risk[1]. In this study, 99.4% of patients (182/183) had Ki-67 indices below 10%, with two-thirds (121/182) having indices under 5%. However, one patient had a Ki-67 index exceeding this threshold, suggesting the potential for malignant schwannoma. This patient is currently under close follow-up.

Treatment selection for GIS primarily depends on the tumor size and location. Although the use of endoscopic resection has significantly increased in recent years, our study supports endoscopic therapies, including EFR, ESD, STER, and snare polypectomy, as effective approaches for treating GIS[5,8,25]. Endoscopic resection is particularly vital for tumors smaller than 3 cm[9,26], offering a minimally invasive nature with a lower risk of complications[27,28]. However, for larger tumors or those in anatomically complex locations, conventional surgical procedures may still be required[29]. Therefore, the choice of surgical approach should be personalized, taking into account the characteristics of the tumor and the overall health of the patient to optimize treatment outcomes.

This study has some limitations. First, as a single-center retrospective study, we could not control for all potential confounders, which may have influenced our findings. Additionally, although this study included a relatively large number of GIS cases compared to that of similar research, the patient population was limited due to the selection criteria. For example, since this study was conducted in a tertiary hospital, the incidence and severity of comorbidities may be higher, as such institutions often treat patients with more complex conditions. These selection biases may restrict the generalizability of our findings to all patients with GIS. Moreover, the follow-up period, ranging from 5-30 months, may have been insufficient to capture late recurrence or long-term complications, potentially underestimating the true risks associated with GIS. Finally, incomplete imaging or endoscopic data and missing immunohistochemical analyses in some patients limited a comprehensive understanding of the disease characteristics. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights for clinicians in diagnosing and treating GIS. Advances in preoperative diagnostic techniques can further reduce unnecessary surgeries, while innovations in endoscopic technology are likely to position endoscopic therapy as the preferred treatment for GIS. Future studies should focus on multi-center studies across diverse regions, incorporating longer follow-up periods to assess outcomes and recurrence rates. Additionally, prospective studies comparing the efficacy and safety of surgical and endoscopic treatments are warranted. Finally, genetic testing and fundamental research are crucial to further explore the mechanisms underlying GIS, its associations with other tumors, and its potential malignant transformation process.

This study examines the clinicopathological characteristics of 229 cases of GIS, highlighting key diagnostic and treatment challenges. The findings indicate that GIS predominantly affects middle-aged and elderly women, with the stomach being the most commonly involved site. Additionally, GIS frequently co-occurs with other malignant tumors. Preope

The authors thank all the patients who provided their data and the doctors and nurses at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University who contributed to this study.

| 1. | Peng H, Han L, Tan Y, Chu Y, Lv L, Liu D, Zhu H. Clinicopathological characteristics of gastrointestinal schwannomas: A retrospective analysis of 78 cases. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1003895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Qi Z, Yang N, Pi M, Yu W. Current status of the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal schwannoma. Oncol Lett. 2021;21:384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Zhong Z, Xu Y, Liu J, Zhang C, Xiao Z, Xia Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Xu Q, Lu Y. Clinicopathological study of gastric schwannoma and review of related literature. BMC Surg. 2022;22:159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Deprez PH, Moons LMG, OʼToole D, Gincul R, Seicean A, Pimentel-Nunes P, Fernández-Esparrach G, Polkowski M, Vieth M, Borbath I, Moreels TG, Nieveen van Dijkum E, Blay JY, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic management of subepithelial lesions including neuroendocrine neoplasms: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022;54:412-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Zhou Y, Zheng S, Ullah S, Zhao L, Liu B. Endoscopic Resection for Gastric Schwannoma: Our Clinical Experience of 28 Cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:2135-2136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Shu Z, Li C, Sun M, Li Z. Intestinal Schwannoma: A Clinicopathological, Immunohistochemical, and Prognostic Study of 9 Cases. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:3414678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Wu CX, Yu QQ, Shou WZ, Zhang K, Zhang ZQ, Bao Q. Benign esophageal schwannoma: A case report and brief overview. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e21527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Zhai YQ, Chai NL, Li HK, Lu ZS, Feng XX, Zhang WG, Liu SZ, Linghu EQ. Endoscopic submucosal excavation and endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastric schwannoma: five-year experience from a large tertiary center in China. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4943-4949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Zhai YQ, Chai NL, Zhang WG, Li HK, Lu ZS, Feng XX, Liu SZ, Linghu EQ. Endoscopic versus surgical resection in the management of gastric schwannomas. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:6132-6138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Morales-Maza J, Pastor-Sifuentes FU, Sánchez-Morales GE, Ramos ES, Santes O, Clemente-Gutiérrez U, Pimienta-Ibarra AS, Medina-Franco H. Clinical characteristics and surgical treatment of schwannomas of the esophagus and stomach: A case series and systematic review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11:750-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Zhang X, Siegelman ES, Lee MK 4th, Tondon R. Pancreatic schwannoma, an extremely rare and challenging entity: Report of two cases and review of literature. Pancreatology. 2019;19:729-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Zhao L, Cao G, Shi Z, Xu J, Yu H, Weng Z, Mao S, Chen Y. Preoperative differentiation of gastric schwannomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on computed tomography: a retrospective multicenter observational study. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1344150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen Z, Yang J, Sun J, Wang P. Gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumours (2-5 cm): Correlation of CT features with malignancy and differential diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2020;123:108783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoo J, Kim SH, Han JK. Multiparametric MRI and (18)F-FDG PET features for differentiating gastrointestinal stromal tumors from benign gastric subepithelial lesions. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:1634-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Lee MW, Kim GH, Kim KB, Kim YH, Park DY, Choi CI, Kim DH, Jeon TY. Digital image analysis-based scoring system for endoscopic ultrasonography is useful in predicting gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:980-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Wang L, Wang Q, Yang L, Ma C, Shi G. Computed tomographic imaging features to differentiate gastric schwannomas from gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a matched case-control study. Sci Rep. 2023;13:17568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kang JH, Kim SH, Kim YH, Rha SE, Hur BY, Han JK. CT Features of Colorectal Schwannomas: Differentiation from Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang J, Xie Z, Zhu X, Niu Z, Ji H, He L, Hu Q, Zhang C. Differentiation of gastric schwannomas from gastrointestinal stromal tumors by CT using machine learning. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46:1773-1782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sekine M, Asano T, Mashima H. The Diagnosis of Small Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Lesions by Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration and Biopsy. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim GH, Ahn JY, Gong CS, Kim M, Na HK, Lee JH, Jung KW, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY. Efficacy of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy in Gastric Subepithelial Tumors Located in the Cardia. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Okuwaki K, Masutani H, Kida M, Yamauchi H, Iwai T, Miyata E, Hasegawa R, Kaneko T, Imaizumi H, Watanabe M, Kurosu T, Tadehara M, Adachi K, Tamaki A, Koizumi W. Diagnostic efficacy of white core cutoff lengths obtained by EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy using a novel 22G franseen biopsy needle and sample isolation processing by stereomicroscopy for subepithelial lesions. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Varshney VK, Yadav T, Elhence P, Sureka B. Preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic schwannoma - Myth or reality. J Cancer Res Ther. 2020;16:S222-S226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hanaoka T, Okuwaki K, Imaizumi H, Imawari Y, Iwai T, Yamauchi H, Hasegawa R, Adachi K, Tadehara M, Kurosu T, Watanabe M, Tamaki A, Kida M, Koizumi W. Pancreatic Schwannoma Diagnosed by Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Aspiration. Intern Med. 2021;60:1389-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yang B, Lu X. The malignancy among gastric submucosal tumor. Transl Cancer Res. 2019;8:2654-2666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lu ZY, Zhao DY. Gastric schwannoma treated by endoscopic full-thickness resection and endoscopic purse-string suture: A case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:3940-3947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Onimaru M, Inoue H, Bechara R, Tanabe M, Abad MRA, Ueno A, Shimamura Y, Sumi K, Ikeda H, Ito H. Clinical outcomes of per-oral endoscopic tumor resection for submucosal tumors in the esophagus and gastric cardia. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:328-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li B, Chen T, Qi ZP, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Shi Q, Cai SL, Sun D, Zhou PH, Zhong YS. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection for small submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer in the gastric fundus. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:2553-2561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang GX, Yu G, Xiang YL, Miu YD, Wang HG, Xu MD. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for large symptomatic submucosal tumors of the esophagus: A clinical analysis of 24 cases. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2020;31:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |