Published online Jan 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i2.99349

Revised: October 25, 2024

Accepted: November 18, 2024

Published online: January 14, 2025

Processing time: 150 Days and 19.9 Hours

Chronic hepatitis B often progresses silently toward hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a leading cause of mortality worldwide. Early detection of HCC is crucial, yet challenging.

To investigate the role of dynamic changes in alkaline phosphatase to prealbumin ratio (APR) in hepatitis B progression to HCC.

Data from 4843 patients with hepatitis B (January 2015 to January 2024) were analyzed. HCC incidence rates in males and females were compared using the log-rank test. Data were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. The Linear Mixed-Effects Model was applied to track the fluctuation of APR levels over time. Furthermore, Joint Modeling of Longitudinal and Survival data was employed to investigate the temporal relationship between APR and HCC risk.

The incidence of HCC was higher in males. To ensure the model’s normality assumption, this study applied a logarithmic transformation to APR, yielding ratio. Ratio levels were higher in females (t = 5.26, P < 0.01). A 1-unit increase in ratio correlated with a 2.005-fold higher risk of HCC in males (95%CI: 1.653-2.431) and a 2.273-fold higher risk in females (95%CI: 1.620-3.190).

Males are more prone to HCC, while females have higher APR levels. Despite no baseline APR link, rising APR indicates a higher HCC risk.

Core Tip: Joint Modeling of Longitudinal and Survival data analysis revealed no association between baseline alkaline phosphatase to prealbumin ratio (APR) levels and Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) risk, yet a significant correlation exists between the increasing trend of APR and heightened HCC risk.

- Citation: Zhen WC, Sun J, Bai XT, Zhang Q, Li ZH, Zhang YX, Xu RX, Wu W, Yao ZH, Pu CW, Li XF. Trends of alkaline phosphatase to prealbumin ratio in patients with hepatitis B linked to hepatocellular carcinoma development. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(2): 99349

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i2/99349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i2.99349

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains an important global public health problem with significant morbidity and mortality[1-3]. About 257 million people worldwide live with chronic HBV infection. HBV causes over 850000 deaths annually and is the most common cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; 44%-55%)[3-7]. In China, hepatitis B-related liver cancer constitutes 90% of liver cancer cases. Despite treatment, the 5-year survival rate of patients with HCC remains low compared to other cancers due to late diagnosis[8]. Growing evidence suggests that the host immune response is crucial in the natural history of HBV infection and HCC development. Among these responses, systemic inflammatory response is a significant component, with its imbalance promoting HCC occurrence[9-12].

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is a hydrolase primarily concentrated in the liver. Cytological studies have shown that high ALP levels may be associated with cancer cell proliferation[13]. Prealbumin (PA), a reliable indicator of inflammatory stress and nutritional status, has a short half-life, rendering it a sensitive biomarker for gauging morbidity, mortality, and tumor progression. Empirical research has demonstrated a significant correlation between PA levels and HCC, suggesting its clinical utility[14,15]. The ALP to PA ratio (APR), introduced by Li et al[16], is a straightforward, accessible, and economical marker of inflammation. High APR can indicate disease outcomes.

In patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), dynamic changes in APR may reflect alterations in the inflammatory and nutritional conditions during disease progression, potentially associated with the risk of HCC development. Previous studies using cross-sectional data have not thoroughly examined APR evolution or its impact on the risk of HCC development. Additionally, traditional survival analysis methods may not accurately identify the complex relationship between APR and HCC risk due to limitations in handling dynamic data.

This study dynamically monitors the APR in patients with CHB using Joint Modeling of Longitudinal and Survival data (JLMS) to analyze the association between APR trends and HCC risk. By collecting multiple follow-up data points, the study constructs a trajectory of APR’s longitudinal changes and assesses their impact on the risk of HCC development using survival analysis models. This research further clarifies the APR mechanism in CHB development and complications and provides new insights and evidence for individualized risk assessment and early intervention.

This study is a single-center retrospective cohort study. Participants were patients diagnosed with CHB who sought medical treatment at a hospital in Dalian City, China, spanning from January 2015 through January 2024. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Dalian Public Health Clinical Center (No. 2024-026KY-001). All data were anonymized.

Inclusion criteria involved the following: (1) CHB diagnosis indicated by positive HBsAg for ≥ 6 months or serum HBV DNA > 2000 IU/mL; (2) Age between 20 and 85 years with complete clinical data; (3) HCC diagnosed via pathological examination or confirmed by liver DSA iodol staining showing tumor staining; (4) Absence of serious complications or organ failure; and (5) Liver cirrhosis diagnosed by imaging or portal hypertension signs.

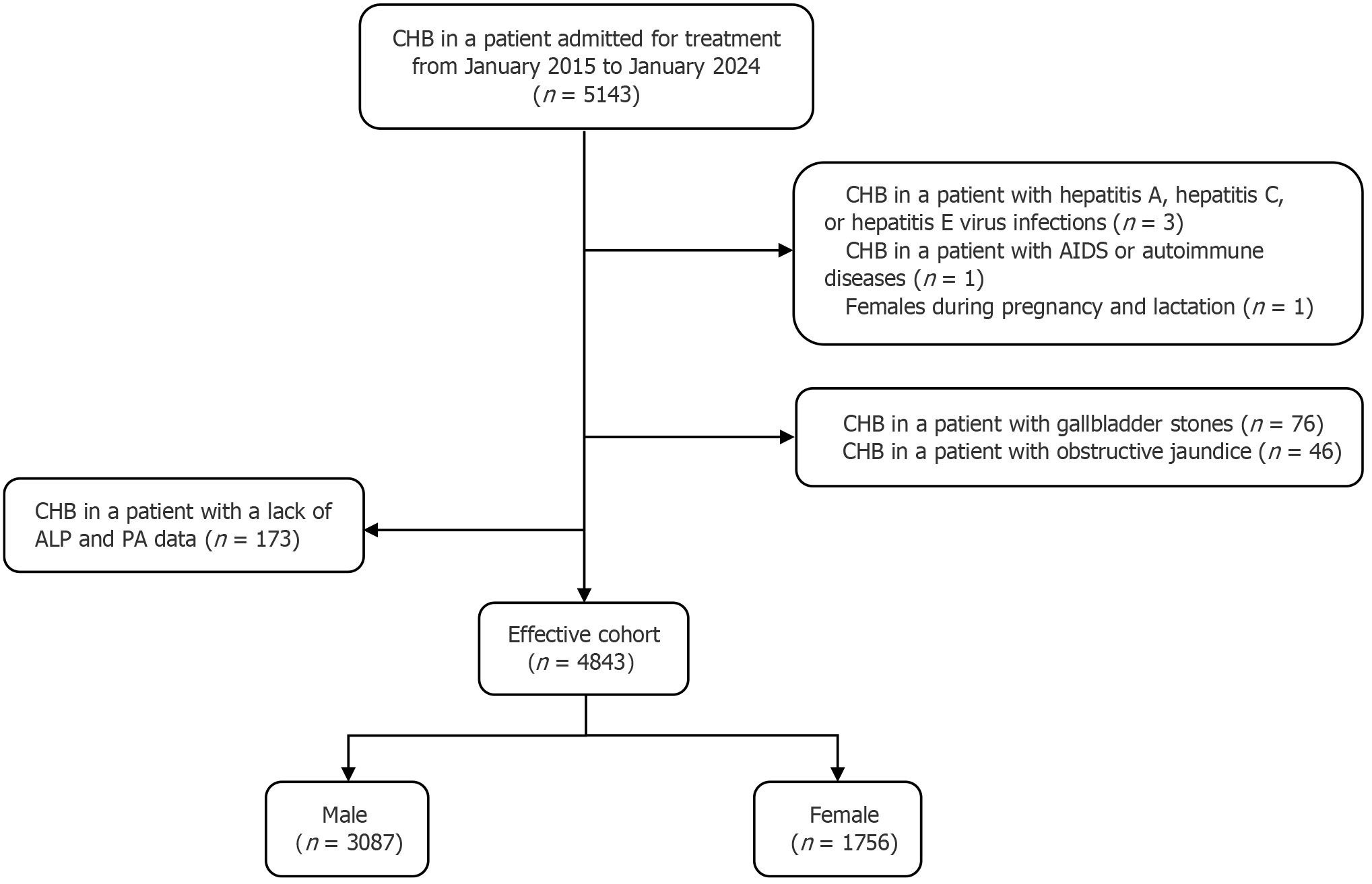

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) CHB in a patient with hepatitis A, hepatitis C, or hepatitis E Virus infections; (2) CHB in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or autoimmune diseases; (3) Pregnancy or lactation; and (4) CHB in a patient with gallbladder stones and obstructive jaundice.

Patients diagnosed with HCC during follow-up or by January 2024 were considered for follow-up termination, with their post-diagnosis data excluded from the study.

From the original cohort of 5143 patients with CHB, 300 were excluded due to missing ALP and PA data or meeting the exclusion criteria (during follow-up). Thus, 4843 patients were included (effective cohort; Figure 1).

Data included age, gender, and results of routine tests (blood-RT, urine-RT, liver function tests, kidney function tests, coagulation function tests), the findings of imaging evaluation (abdominal ultrasound, upper abdominal computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, etc.), and pathological diagnosis.

Normally distributed data are reported as mean ± SD. Non-normally distributed continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables, expressed as frequencies and percentages, are compared utilizing χ2. The analysis was conducted using SPSS 27.0 and R 4.3.3, with P < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. HCC incidence rates in males and females were compared using the log-rank test. Data were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Linear Mixed-Effects Models (LMEs) were employed to assess the temporal dynamics of APR in patients with CHB. JMLS was utilized to evaluate the longitudinal association between APR and HCC. Variable generation (for the models) and model principles[17,18] are outlined in Supplementary material 1.

Baseline reference was established using initial data from participants fulfilling the inclusion criteria, with each contributing at least two data points. The primary outcome was HCC diagnosis during follow-up, denoted by setting their status in the respective year to 1. To meet the model’s assumption of normal distribution, a logarithmic transformation was applied to APR values, particularly ln(10APR), referenced as the ratio.

The fundamental descriptions of the variables are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (Supplementary material 1); the variable setup for the models is detailed in Supplementary material 2. Full model equations for LME and JMLS are included in Supplementary Table 2.

All abbreviations in this study are explained in Supplementary Table 3 (Supplementary material 2).

Study cohort inclusion and follow-up: The study sample comprised 5143 individuals, forming the original cohort. After applying the exclusion criteria, 4843 patients (effective cohort) were analyzed. Supplementary Table 4 (Supplementary material 2) demonstrates that the effective cohort is representative of the original cohort.

The effective cohort consisted of 3087 males (63.74%) and 1756 females (34.51%), with ages at baseline spanning from 20 to 85 years. The overall median baseline age was 49 years, with males averaging 49 years and females 50 years. The median follow-up duration for the entire study population was 4.22 years (IQR: 2.24-6.0), with males at 4.20 years (IQR: 2.23-6.02) and females at 4.23 years (IQR: 2.25-6.11).

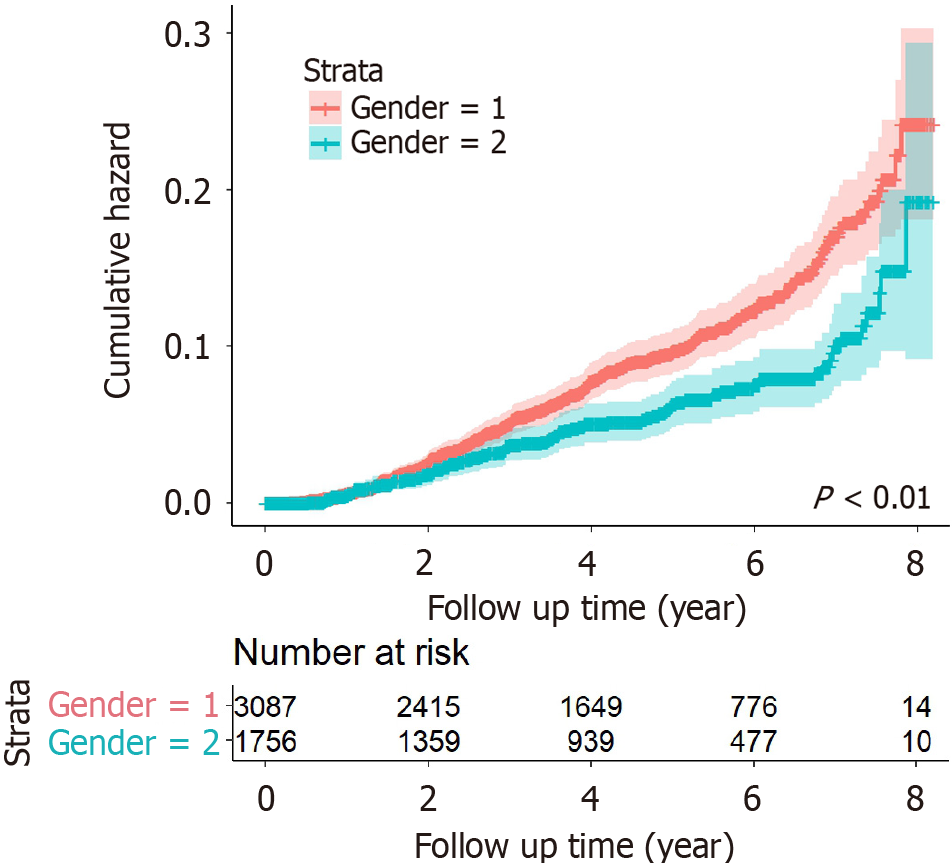

HCC occurrence during follow-up: During follow-up, 355 patients with CHB developed HCC, with a cumulative incidence of 7.33% and an incidence density of 0.81/100 PY. Among them, 261 males had a higher cumulative incidence (8.45%) and density (0.94/100 PY), while 94 females had lower rates (5.35% and 0.59/100 PY). The Log-rank test showed a statistically significant gender difference in HCC incidence (P < 0.01; Figure 2).

Supplementary Table 5 indicates that the average APR levels in the HCC group consistently exceeded those in the non-HCC group across all follow-up years for both genders. APR levels declined over time and were higher in females than males, with significant differences observed between follow-up years (P < 0.01).

LME for the overall population (LME1) shows that the ratio in females was higher than in males by 0.085. For non-HCC patients, the average annual growth rate of the ratio was -0.093. The annual growth rate increased by 0.003 in those who were 1 year older at baseline (Table 1).

| Variable | LME1 (total) | LME2 (males) | LME3 (females) | |||

| β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | |

| Intercept | 1.147 | < 0.01 | 1.234 | < 0.01 | 1.292 | < 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.085 | < 0.01 | - | - | - | - |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.456 | < 0.01 | 0.446 | < 0.01 | 0.458 | < 0.01 |

| Time | -0.093 | < 0.01 | -0.093 | < 0.01 | -0.089 | < 0.01 |

| Cage | -0.002 | < 0.01 | -0.006 | < 0.01 | 0.005 | < 0.01 |

| State | 0.314 | < 0.01 | 0.325 | < 0.01 | 0.317 | < 0.01 |

| Time:Cage | 0.003 | < 0.01 | 0.004 | < 0.01 | 0.002 | < 0.01 |

| Time:State | 0.006 | > 0.05 | 0.006 | > 0.05 | -0.003 | > 0.05 |

The LME for males and LME for females, derived from the LME1 model by incorporating gender as a stratification factor, reveal the following outcomes. At baseline, males with cirrhosis had a ratio 0.446 units higher than those without cirrhosis, while females with cirrhosis exhibited a ratio 0.458 units higher. Additionally, for every year increase in baseline age, the average ratio for males decreased by 0.006, whereas for females, it increased by 0.005. Male patients with HCC showed an average ratio 0.325 higher than their non-HCC counterparts, who averaged 1.234. Conversely, female patients with HCC had an average ratio 0.317 higher than female non-HCC patients, who averaged 1.239. Among male non-HCC patients, the average annual ratio decrease was -0.093; a 1-year increase in baseline age yielded an annual ratio increase of 0.003. Among female non-HCC patients, the average annual growth rate of the ratio was -0.089; an increase of 1 year in baseline age correlated with an annual ratio decrease of 0.002. Statistical analysis is detailed in the Supplementary Tables 6, 7 and 8.

Table 2 illustrates the results from the survival sub-models of JMLS in terms of the HR (95%CI) and P value. All the JMLS are time-dependent relative risk models with a baseline risk function. Thus, HRs can be interpreted similarly to those from a proportional hazard model, such as a Cox PH model. JMLS for the overall population (JMLS1) exhibits an HR of 2.065 (1.749-2.439) suggesting a 2.065-fold increase in the hazard of HCC per unit increase of ratio.

| Variable | JMLS1 (total) | JMLS2 (males) | JMLS3 (females) | |||

| HR | P value | HR | P value | HR | P value | |

| Ratio | 1.069 (0.923–1.216) | > 0.05 | 1.034 (0.882–1.213) | > 0.05 | 1.149 (0.865–1.526) | > 0.05 |

| Cage | 1.069 (1.057–1.081) | < 0.01 | 1.068 (1.055, 1.082) | < 0.01 | 1.071 (1.045–1.098) | < 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.480 (0.377–0.610) | < 0.01 | - | - | - | - |

| Liver cirrhosis | 4.570 (3.376–6.185) | < 0.01 | 4.896 (3.428, 6.994) | < 0.01 | 3.690 (2.075–6.561) | < 0.01 |

| α | 2.065 (1.749-2.439) | < 0.01 | 2.005 (1.653–2.431) | < 0.01 | 2.273 (1.620–3.190) | < 0.01 |

The JMLS for males (JMLS2) and JMLS for females (JMLS3), derived from JMLS1 by incorporating gender as a stratification factor, demonstrate the following outcomes. JMLS2 exhibits an HR of 2.005 (1.653-2.431), suggesting a 2.005-fold increase in the hazard of HCC per unit increase in the ratio. JMLS3 exhibits an HR of 2.273 (1.620-3.190), suggesting a 2.237-fold increase in the hazard of HCC per unit increase in the ratio. Detailed statistical analysis is included in Supplementary Tables 9, 10 and 11.

Notably, all three models suggest that baseline ratio levels are not associated with HCC risk, whereas the longitudinal increase in the ratio elevates HCC risk.

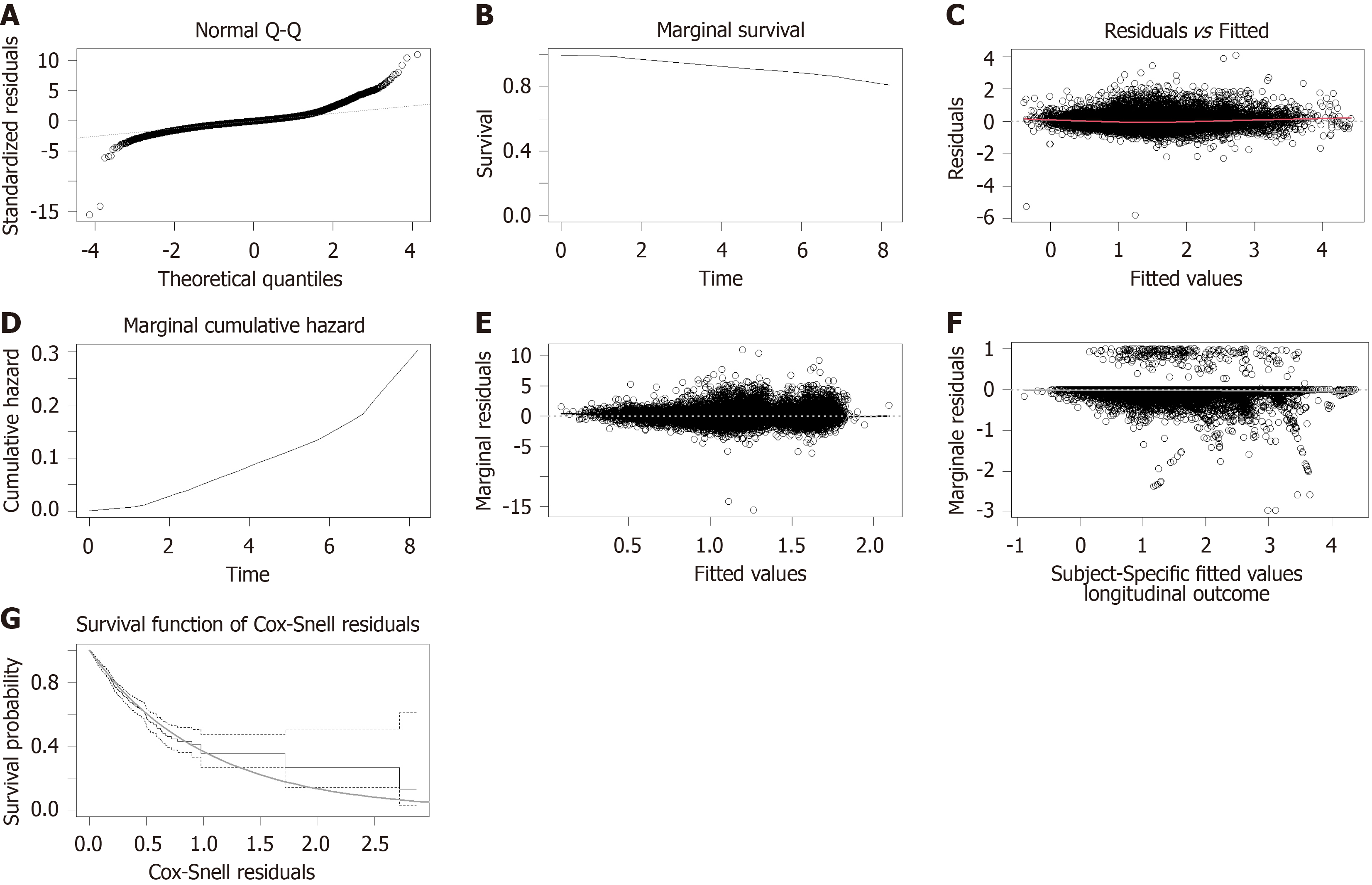

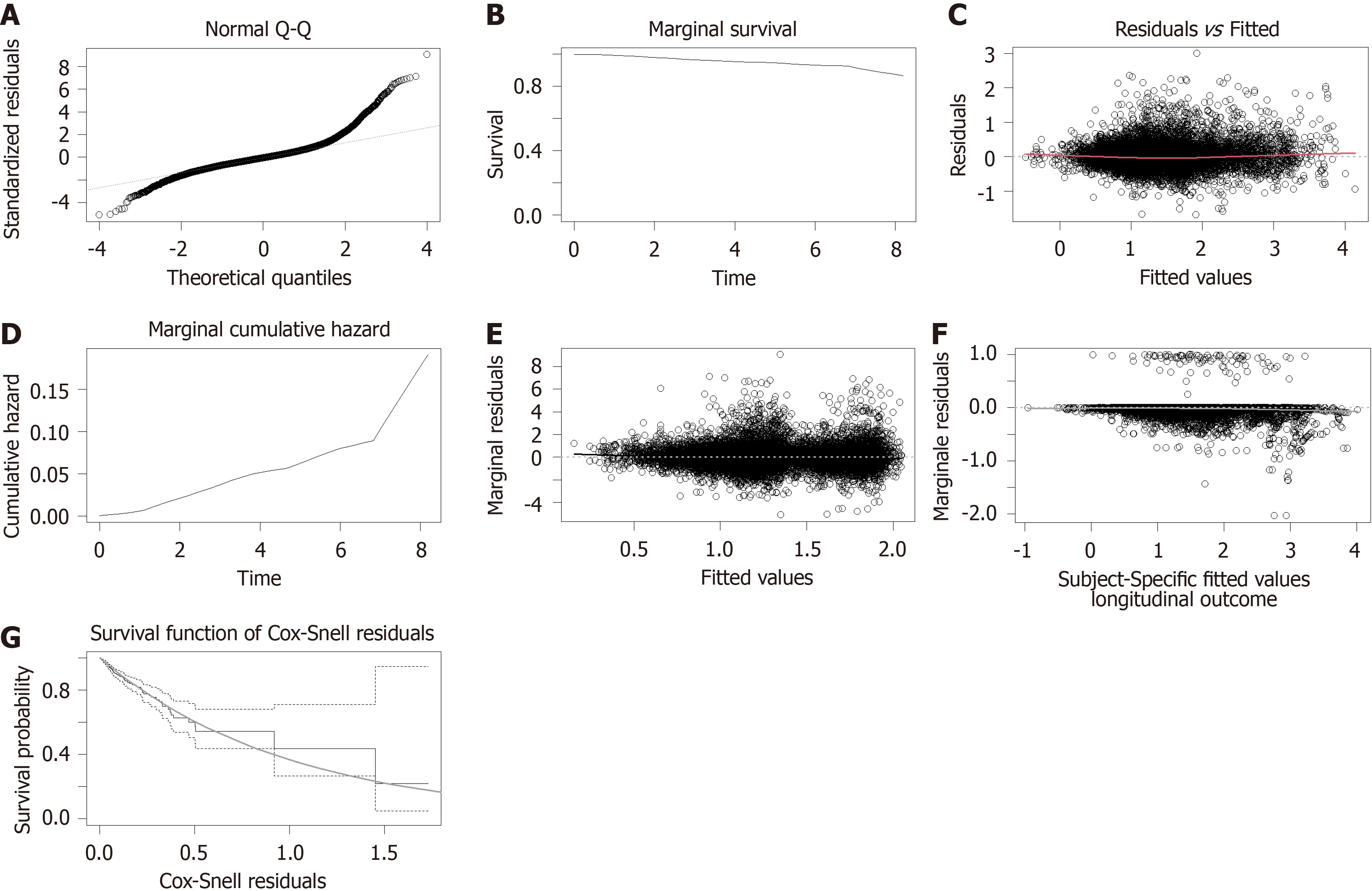

Upon examining the diagnostic outcomes, it became evident that the model fit was satisfactory for both male and female cohorts. This conclusion is supported by the residual Q-Q plots that align with normality, the marginal survival and cumulative hazard function estimation curves that closely match their theoretical values, and the Martingale and Cox-Snell residuals that are appropriately centered around zero. Notably, in E-th sub-figure, the solid black line, which depicts the Loess smoothing curve fitted to the standardized edge residuals, hovers near zero, indicating an excellent fit for both genders. Likewise, in F-th sub-figure, the gray Loess smoothing curve, based on the martingale residuals, stays near the horizontal axis at zero, signifying that the model assumptions regarding the relationship between the time-dependent longitudinal component and the risk function hold true for both genders (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

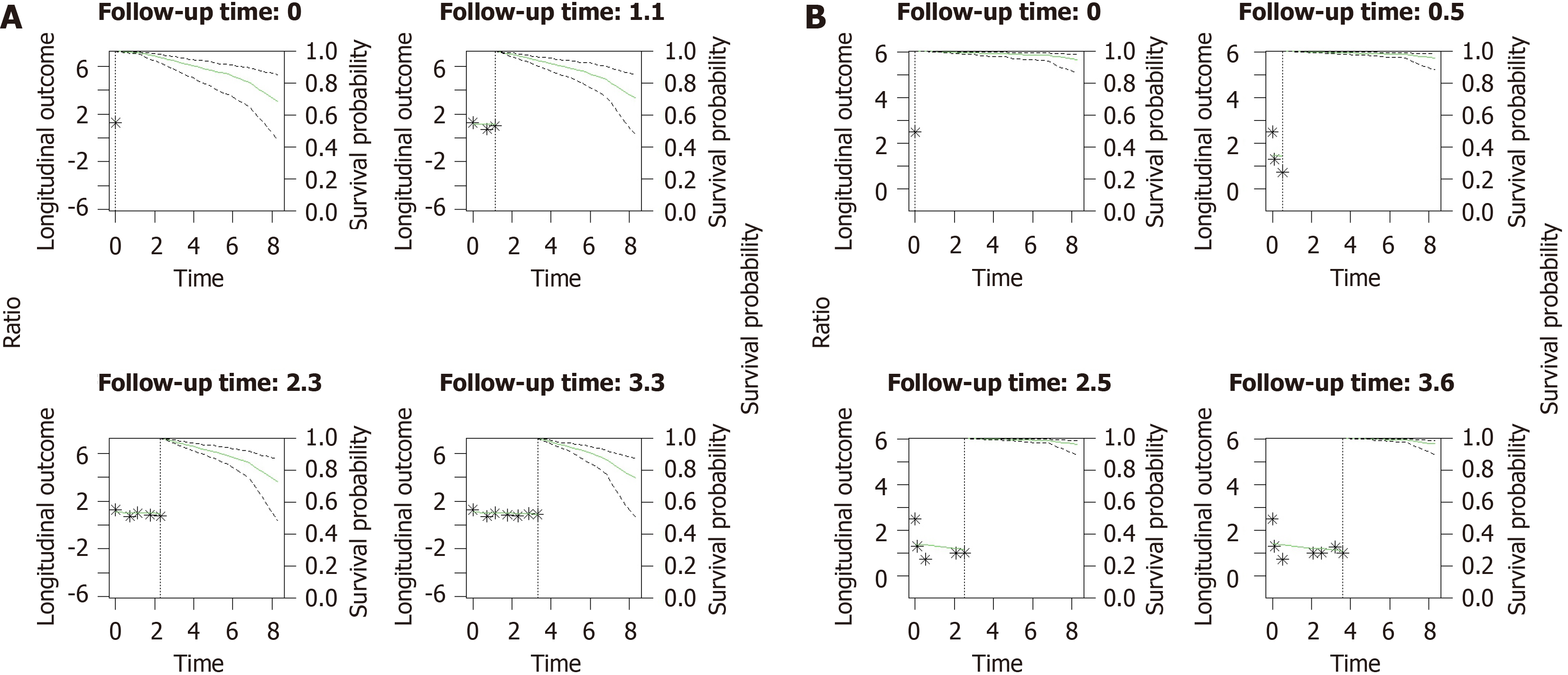

Figure 5 and Supplementary Tables 12 and 13 show predictions of JMLS for survival rates in male and female patients with CHB at median age. The model estimates a 10-year survival probability of 72% (95%CI: 0.54-0.85) for males and 95% (95%CI: 0.87-0.98) for females.

HBV infection accounts for the majority of liver cancer cases in most Asian countries, with prevalence rates reaching 60%-80% in endemic areas[19]. Risk factors for HCC in carriers of HBV include male sex, older age, family history, viral type, and cirrhosis[5]. In sub-Saharan Africa, HBV-related HCC is diagnosed at a median age of 45 years[20], compared to 52, 69, 65, and 62 years in China, Japan, Europe, and North America, respectively[21,22].

This retrospective cohort study shows that the cumulative incidence of HCC in patients with CHB is 7.33%. The incidence was higher in males (8.45%) than females (5.35%). Most studies have found that HCC incidence and mortality vary by sex, with males being 1.2-3.6 times more likely than females to develop HCC[23,24]. A cohort study by Liao et al[25] similarly showed that men are at higher risk of being diagnosed with HCC than women, with an HR of 3.9 (95%CI: 3.6-4.2) for HCC. Similarly, this study found that men have a higher incidence of HCC than women. Gender differences in HCC incidence can be attributed to several factors, such as higher prevalence of intravenous drug use, viral infections, and excessive alcohol consumption in men, as well as differences in sex hormones[26,27]. A clinical trial has shown that testosterone can promote HCC development by reducing the activity of inhibitory enzymes[28]. Additionally, another clinical study has shown that estrogen protects against HCC development through estrogen-mediated inhibition of IL-6 production by Kupffer cells[29].

ALP is an enzyme widely distributed in the liver, bone, intestine, kidney, placenta, and various tumors. ALP is crucial in regulating inflammatory responses and immune functions and can be used to predict liver cancer rupture, assist in tumor imaging, and differentiate bone tumors[30-32]. PA, primarily produced by the liver, is a sensitive biomarker for plasma proteins and reliably indicates a patient’s nutritional status and liver disease severity[33,34]. ALP serves as an independent predictor of significant liver inflammation; preoperative levels can help in monitoring recurrence in patients at high risk for HCC[35]. Additionally, a low PA level independently indicates shorter overall survival[36]. During HCC progression, the APR may undergo dynamic changes. These changes may be associated with tumor growth, treatment efficacy, and the patient’s physiological state. Monitoring these changes can help predict the occurrence and development of HCC more intuitively.

Our LME1 results showed a higher baseline APR level in females than males. The results of the models showed that the average APR level in the baseline HCC group was higher than in the non-HCC group in both sex groups. Mean APR levels were lower in older males at baseline but tended to increase with age. In older females, mean APR levels were higher at baseline but also tended to increase with age.

JMLS is a model that allows for the simultaneous analysis of longitudinal repeated covariates and event time data[37]. JMLS is used to assess the association of a biomarker with the hazard of an event. It serves as a sensitivity analysis to reduce bias due to censoring or mortality. It also enables personalized prognostication by accounting for measurement error, different follow-up times, and efficiency through combining data (i.e., smaller standard error)[38]. In this study, all APR measurements from the past 9 years for each participant were included in the model analysis. The dynamic change of APR was analyzed using the LME; the association between the longitudinal change of APR and HCC was analyzed by combining the COX model. The results show that a longitudinal increase in APR increases HCC risk. Specifically, the longitudinal increase in the ratio was a risk factor for HCC in both males (HR = 2.005, 95%CI: 1.653-2.431) and females (HR = 2.273, 95%CI: 1.620-3.190). JLMS revealed that an increase in APR would increase HCC risk; the HCC risk was not related to baseline APR levels in individual subjects. However, the longitudinal dynamic change in individual APR significantly impacted HCC development. Additionally, this study found that age and baseline cirrhosis were risk factors for HCC in both male and female groups. Males’ HCC risk increased by 1.068-fold annually (95%CI: 1.055-1.082). Patients with baseline cirrhosis had a 4.896 times higher HCC risk (95%CI: 3.428-6.994). Females also had a 1.071-fold annual increase in HCC risk (95%CI: 1.045-1.097); those with baseline cirrhosis have a 3.690 times higher risk (95%CI: 2.075-6.561). An increase in the APR indicates a rise in ALP levels and a decrease in PA levels. Hann et al[18] found that ALP elevation was associated with HCC development. Huo et al[39] and Zhou et al[40] found a close relationship between reduced PA levels and postoperative adverse outcomes in patients with cancers (e.g., in the liver or stomach). These studies align with our results. The physiological effects of ALP and PA are complex and diverse. Although the exact pathophysiological relationship cannot be determined from our data, the current results may help further research clarify the association between APR levels and HCC risk in those with HBV.

Clinicians often rely on biomarker trends for decision-making, making it crucial to understand how these parameters link to clinical practice. This study highlights gender differences in HCC risk factors, facilitating personalized medical strategies. These strategies involve customized prevention and treatment plans based on gender and APR levels. Furthermore, we advocate for additional research, especially into the causes of non-cirrhotic HCC in women, to develop more effective methods of prevention and treatment. Timely identification and treatment of HCC can significantly enhance patient outcomes and survival rates, thereby reducing HCC-related mortality. Supplementary Table 14 concisely summarizes existing studies on the role of inflammatory markers in disease progression in patients with CHB. Thus, our study further consolidates the relationship between inflammatory markers and fibrosis, providing new insights that enrich the current scientific discourse.

This study has several limitations. First, the study’s population composition ratio varies significantly between genders; relying solely on data from one hospital population may introduce selection biases. Selection bias occurs when the study sample differs from the larger population in characteristics or behaviors, potentially yielding inaccurate effect estimates. Despite the steps taken to ensure a representative sample, our sample may not fully reflect the broader population. Future research should consider larger and more diverse samples to mitigate the risk of selection bias and enhance the generalizability of the findings. Second, the follow-up period is insufficient to observe the dynamic changes of APR and its relationship with HCC in patients with CHB. Third, joint modeling assumes that censoring is independent of random effects. Violation of this assumption would bias parameter estimates. However, simulation studies suggest that joint models’ estimates are robust to misspecification of the distribution of random effects[37].

HCC incidence rates were higher in males, with females exhibiting higher APR levels. Baseline APR levels did not predict HCC risk. However, an increasing APR over time correlated with an elevated HCC risk in both genders.

| 1. | Mathkar PP, Chen X, Sulovari A, Li D. Characterization of Hepatitis B Virus Integrations Identified in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Genomes. Viruses. 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Salerno D, Chiodo L, Alfano V, Floriot O, Cottone G, Paturel A, Pallocca M, Plissonnier ML, Jeddari S, Belloni L, Zeisel M, Levrero M, Guerrieri F. Hepatitis B protein HBx binds the DLEU2 lncRNA to sustain cccDNA and host cancer-related gene transcription. Gut. 2020;69:2016-2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. ; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3801] [Article Influence: 475.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Sagnelli E, Macera M, Russo A, Coppola N, Sagnelli C. Epidemiological and etiological variations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Infection. 2020;48:7-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shen C, Jiang X, Li M, Luo Y. Hepatitis Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Recent Advances. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration, Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, Al-Raddadi R, Alvis-Guzman N, Amoako Y, Artaman A, Ayele TA, Barac A, Bensenor I, Berhane A, Bhutta Z, Castillo-Rivas J, Chitheer A, Choi JY, Cowie B, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dey S, Dicker D, Phuc H, Ekwueme DU, Zaki MS, Fischer F, Fürst T, Hancock J, Hay SI, Hotez P, Jee SH, Kasaeian A, Khader Y, Khang YH, Kumar A, Kutz M, Larson H, Lopez A, Lunevicius R, Malekzadeh R, McAlinden C, Meier T, Mendoza W, Mokdad A, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nagel G, Nguyen Q, Nguyen G, Ogbo F, Patton G, Pereira DM, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Radfar A, Roshandel G, Salomon JA, Sanabria J, Sartorius B, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Sepanlou S, Shackelford K, Shore H, Sun J, Mengistu DT, Topór-Mądry R, Tran B, Ukwaja KN, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wakayo T, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Yonemoto N, Younis M, Yu C, Zaidi Z, Zhu L, Murray CJL, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1683-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1459] [Cited by in RCA: 1499] [Article Influence: 187.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C, Vos T, Abubakar I, Abu-Raddad LJ, Assadi R, Bhala N, Cowie B, Forouzanfour MH, Groeger J, Hanafiah KM, Jacobsen KH, James SL, MacLachlan J, Malekzadeh R, Martin NK, Mokdad AA, Mokdad AH, Murray CJL, Plass D, Rana S, Rein DB, Richardus JH, Sanabria J, Saylan M, Shahraz S, So S, Vlassov VV, Weiderpass E, Wiersma ST, Younis M, Yu C, El Sayed Zaki M, Cooke GS. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388:1081-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1042] [Cited by in RCA: 989] [Article Influence: 109.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang W, Wei C. Advances in the early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dis. 2020;7:308-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 58.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Deng Y, Du Y, Zhang Q, Han X, Cao G. Human cytidine deaminases facilitate hepatitis B virus evolution and link inflammation and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2014;343:161-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khanam A, Chua JV, Kottilil S. Immunopathology of Chronic Hepatitis B Infection: Role of Innate and Adaptive Immune Response in Disease Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cho HJ, Cheong JY. Role of Immune Cells in Patients with Hepatitis B Virus-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yu LX, Ling Y, Wang HY. Role of nonresolving inflammation in hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2018;2:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li Q, Lyu Z, Wang L, Li F, Yang Z, Ren W. Albumin-to-Alkaline Phosphatase Ratio Associates with Good Prognosis of Hepatitis B Virus-Positive HCC Patients. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:2377-2384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang F, Wei L, Huo X, Ding Y, Zhou X, Liu D. Effects of early postoperative enteral nutrition versus usual care on serum albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, time to first flatus and postoperative hospital stay for patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Contemp Nurse. 2018;54:561-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li L, Mo F, Hui EP, Chan SL, Koh J, Tang NLS, Yu SCH, Yeo W. The association of liver function and quality of life of patients with liver cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li Y, Wang JS, Guo Y, Zhang T, Li LP. Use of the alkaline phosphatase to prealbumin ratio as an independent predictive factor for the prognosis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:6963-6978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Madathil AK, Ghaskadbi S, Kalamkar S, Goel P. Pune GSH supplementation study: Analyzing longitudinal changes in type 2 diabetic patients using linear mixed-effects models. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1139673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hann HW, Wan S, Myers RE, Hann RS, Xing J, Chen B, Yang H. Comprehensive analysis of common serum liver enzymes as prospective predictors of hepatocellular carcinoma in HBV patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Singal AG, Kanwal F, Llovet JM. Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:864-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 174.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Spearman CW, Dusheiko G, Jonas E, Abdo A, Afihene M, Cunha L, Desalegn H, Kassianides C, Katsidzira L, Kramvis A, Lam P, Lesi OA, Micah EA, Musabeyezu E, Ndow G, Nnabuchi CV, Ocama P, Okeke E, Rwegasha J, Shewaye AB, Some FF, Tzeuton C, Sonderup MW; Gastroenterology and Hepatology Association of sub-Saharan Africa (GHASSA). Hepatocellular carcinoma: measures to improve the outlook in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:1036-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Toh MR, Wong EYT, Wong SH, Ng AWT, Loo LH, Chow PK, Ngeow J. Global Epidemiology and Genetics of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:766-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Duberg AS, Lybeck C, Fält A, Montgomery S, Aleman S. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by age and country of origin in people living in Sweden: A national register study. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:2418-2430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, Laversanne M, McGlynn KA, Soerjomataram I. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1598-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 1068] [Article Influence: 356.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tan DJH, Setiawan VW, Ng CH, Lim WH, Muthiah MD, Tan EX, Dan YY, Roberts LR, Loomba R, Huang DQ. Global burden of liver cancer in males and females: Changing etiological basis and the growing contribution of NASH. Hepatology. 2023;77:1150-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liao W, Coupland CAC, Innes H, Jepsen P, Matthews PC, Campbell C; DeLIVER consortium, Barnes E, Hippisley-Cox J. Disparities in care and outcomes for primary liver cancer in England during 2008-2018: a cohort study of 8.52 million primary care population using the QResearch database. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;59:101969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rich NE, Murphy CC, Yopp AC, Tiro J, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Sex disparities in presentation and prognosis of 1110 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:701-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Ye Z, Yang S, Liu M, Wu Q, Zhou C, He P, Gan X, Qin X. Mobile Phone Use and Risks of Overall and 25 Site-Specific Cancers: A Prospective Study from the UK Biobank Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2024;33:88-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Manieri E, Herrera-Melle L, Mora A, Tomás-Loba A, Leiva-Vega L, Fernández DI, Rodríguez E, Morán L, Hernández-Cosido L, Torres JL, Seoane LM, Cubero FJ, Marcos M, Sabio G. Adiponectin accounts for gender differences in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1108-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nevola R, Tortorella G, Rosato V, Rinaldi L, Imbriani S, Perillo P, Mastrocinque D, La Montagna M, Russo A, Di Lorenzo G, Alfano M, Rocco M, Ricozzi C, Gjeloshi K, Sasso FC, Marfella R, Marrone A, Kondili LA, Esposito N, Claar E, Cozzolino D. Gender Differences in the Pathogenesis and Risk Factors of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology (Basel). 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Haarhaus M, Brandenburg V, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Stenvinkel P, Magnusson P. Alkaline phosphatase: a novel treatment target for cardiovascular disease in CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:429-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Xia F, Ndhlovu E, Liu Z, Chen X, Zhang B, Zhu P. Alpha-Fetoprotein+Alkaline Phosphatase (A-A) Score Can Predict the Prognosis of Patients with Ruptured Hepatocellular Carcinoma Underwent Hepatectomy. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:9934189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yang Y, Zhang M, Zhang W, Chen Y, Zhang T, Chen S, Yuan Y, Liang G, Zhang S. Sensitive sensing of alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyltranspeptidase activity for tumor imaging. Analyst. 2022;147:1544-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dellière S, Cynober L. Is transthyretin a good marker of nutritional status? Clin Nutr. 2017;36:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Young GA, Hill GL. Assessment of protein-calorie malnutrition in surgical patients from plasma proteins and anthropometric measurements. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31:429-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhan J, Wang J, Zhang Z, Xue R, Jiang S, Liu J, Liu Y, Zhu L, Xia J, Yan X, Ding W, Zhu C, Qiu Y, Li J, Huang R, Wu C. Noninvasive diagnosis of significant liver inflammation in patients with chronic hepatitis B in the indeterminate phase. Virulence. 2023;14:2268497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lei K, Wang JG, Li Y, Wang HX, Xu J, You K, Liu ZJ. Prognostic value of preoperative prealbumin levels in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation. Heliyon. 2023;9:e18494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Miller RG, Anderson SJ, Costacou T, Sekikawa A, Orchard TJ. Hemoglobin A1c Level and Cardiovascular Disease Incidence in Persons With Type 1 Diabetes: An Application of Joint Modeling of Longitudinal and Time-to-Event Data in the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:1520-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Field RJ, Adamson C, Jhund P, Lewsey J. Joint modelling of longitudinal processes and time-to-event outcomes in heart failure: systematic review and exemplar examining the relationship between serum digoxin levels and mortality. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2023;23:94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Huo RR, Liu HT, Deng ZJ, Liang XM, Gong WF, Qi LN, You XM, Xiang BD, Li LQ, Ma L, Zhong JH. Dose-Response Between Serum Prealbumin and All-Cause Mortality After Hepatectomy in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:596691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Zhou J, Hiki N, Mine S, Kumagai K, Ida S, Jiang X, Nunobe S, Ohashi M, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Role of Prealbumin as a Powerful and Simple Index for Predicting Postoperative Complications After Gastric Cancer Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:510-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |