Published online May 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i17.105281

Revised: March 7, 2025

Accepted: April 17, 2025

Published online: May 7, 2025

Processing time: 102 Days and 17.7 Hours

Reflux hypersensitivity (RH) constitutes roughly 14% of patients with heartburn and 34% of those with refractory heartburn, yet it is inadequately comprehended.

To investigate the clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with RH.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 109 patients with RH and 384 healthy controls from three medical centers between January 2022 and December 2023. Comprehensive data encompassing symptoms, motility, impedance-pH moni

RH patients encountered a greater frequency of weakly acidic reflux (WAR) events compared to acidic reflux or nonacidic reflux (NAR) events. Upright reflux time (1.22%) exceeds supine reflux time (0.54%) (P < 0.05). Extraesophageal symptoms were more prevalent among younger patients and those with elevated NAR (P < 0.05). The acidic reflux, WAR, NAR, and peristaltic contraction break length in male patients exceeded those in female patients (P < 0.05). Age [odds ratio (OR) = 5.633], hiatal hernia (OR = 13.103), and anxiety (OR = 17.342) constituted independent risk factors for RH.

WAR and NAR are pivotal in RH. Patients with increased NAR are more likely to experience extraesophageal symptoms. Age, hiatal hernia, and anxiety are significant independent risk factors for RH.

Core Tip: Reflux hypersensitivity (RH) significantly contributes to heartburn. However, its underlying mechanisms are not fully comprehended. This retrospective study examined data from 92 patients diagnosed with RH and 104 healthy controls to explore clinical characteristics and potential risk factors. The results demonstrate that weakly acidic reflux and nonacidic reflux are integral to the pathophysiology of RH. Furthermore, extraesophageal symptoms were correlated with a younger age and elevated levels of nonacidic reflux. Independent risk factors identified for RH encompass age, the existence of a hiatal hernia, and anxiety. These findings highlight the intricate relationship between reflux subtypes and psychological factors in RH, offering new perspectives for individualized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

- Citation: Wu YP, Zhou JX, Wu HB, Wu DP, Qin LZ, Qin B, Xu XY, Yehya SAA, Cheng Y. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of esophageal reflux hypersensitivity: A multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(17): 105281

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i17/105281.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i17.105281

Reflux hypersensitivity (RH) is a functional esophageal disorder marked by heartburn or chest pain induced by reflux events within normal physiological limits, with no observable abnormalities on endoscopy, as delineated by the Rome IV criteria[1]. Patients with RH exhibit increased esophageal sensitivity, interpreting non-painful stimuli as painful and exhibiting amplified reactions to painful stimuli[2]. RH is a significant yet under-recognized component of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), comprising roughly 14% of all heartburn instances and 34% of refractory heartburn occurrences[3,4].

The pathophysiology of RH is intricate and multifaceted. Central and peripheral sensitization of the nervous system are crucial, with abnormal signal processing leading to an intensified perception of reflux events[5]. Psychological factors, such as anxiety and stress, exacerbate symptom perception and are closely linked to the onset and persistence of RH[6]. In addition, reflux characteristics, including weakly acidic reflux (WAR) and nonacidic reflux (NAR), have been recognized as significant factors in symptom manifestation[7].

Despite its clinical importance, RH is inadequately comprehended, chiefly owing to diagnostic difficulties and res

This study retrospectively examines data from a substantial cohort of RH patients across three medical centers, concentrating on reflux patterns, esophageal motility, extraesophageal symptoms (EES), and psychological factors to address existing gaps. This research is focused on clarifying independent risk factors, such as age, hiatal hernia, and anxiety, to improve the comprehension of RH and establish a basis for more effective diagnostic and management approaches.

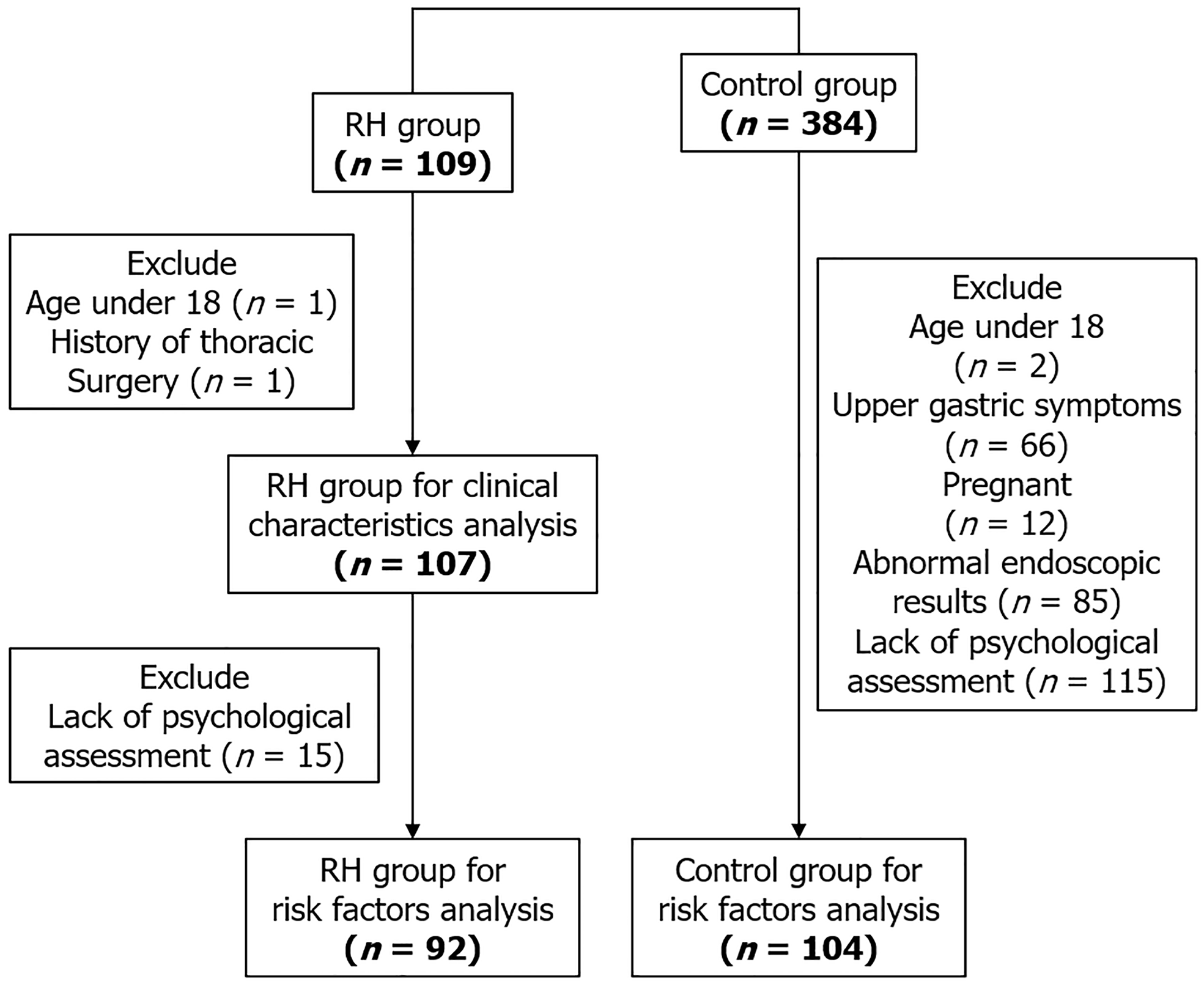

This study conducted a retrospective review of medical records for patients diagnosed with RH based on the Rome IV criteria. Data were gathered from three medical centers in China from January 2022 to December 2023. Clinical data, encompassing gastroscopy findings, 24-hour multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH (MII-pH) monitoring, and esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM), was evaluated. Symptom correlation was evaluated using a symptom index of ≥ 50% and/or a symptom association probability of ≥ 95%[10]. The interpretation of HRM was performed in accordance with the Chicago Classification version 4.0[11]. Figure 1 delineates the participant enrollment and exclusion procedures.

Esophageal HRM and 24-hour MII-pH monitoring were conducted following an overnight fast and cessation of antacid therapy for a minimum duration of one week. Esophageal HRM were conducted utilizing a 22-channel liquid perfusion system (MMS, Netherlands). A 36-channel catheter was transnasally inserted to measure esophageal pressure from the stomach to the upper esophageal sphincter. A 30-second baseline recording was acquired and ten 5-mL water swallows.

MII-pH monitoring was performed using an Ohmega dynamic impedance-pH monitoring system (MMS, Netherlands) for a continuous duration of 24 hours. A pH sensor was situated 5 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), accompanied by six impedance sensors located at 3, 5, 7, 9, 15, and 17 cm above the LES to identify reflux events. Data were systematically recorded, with distinct analyses performed for diurnal (6 AM to 6 PM) and nocturnal (6 PM to 6 AM) intervals. Reflux episodes were categorized as acidic reflux (AR) (pH < 4), WAR: 4 ≤ pH < 7, or NAR: pH ≥ 7.

Demographic and clinical information was obtained from medical records. Psychological evaluations were performed utilizing the 24-item Hamilton Anxiety Scale and the 24-item Hamilton Depression Scale to assess mental health status.

Categorical variables were represented as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were depicted as medians with interquartile ranges. The Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for multiple-group comparisons, and the Mann-Whitney U test was employed for two-group comparisons, owing to the non-normal distribution of the data. Categorical variables were assessed using the χ² test.

A univariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify potential risk factors for RH. Variables with P < 0.1 were incorporated into the multivariate logistic regression model. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were computed to evaluate the strength of associations. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 26.0). The statistical methods used in this study were reviewed by Yuan Shen from the School of Mathematics and Statistics at Xi’an Jiaotong University.

All patients participating in the study provided informed consent. The Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University approved the study (Approval number: 2023262).

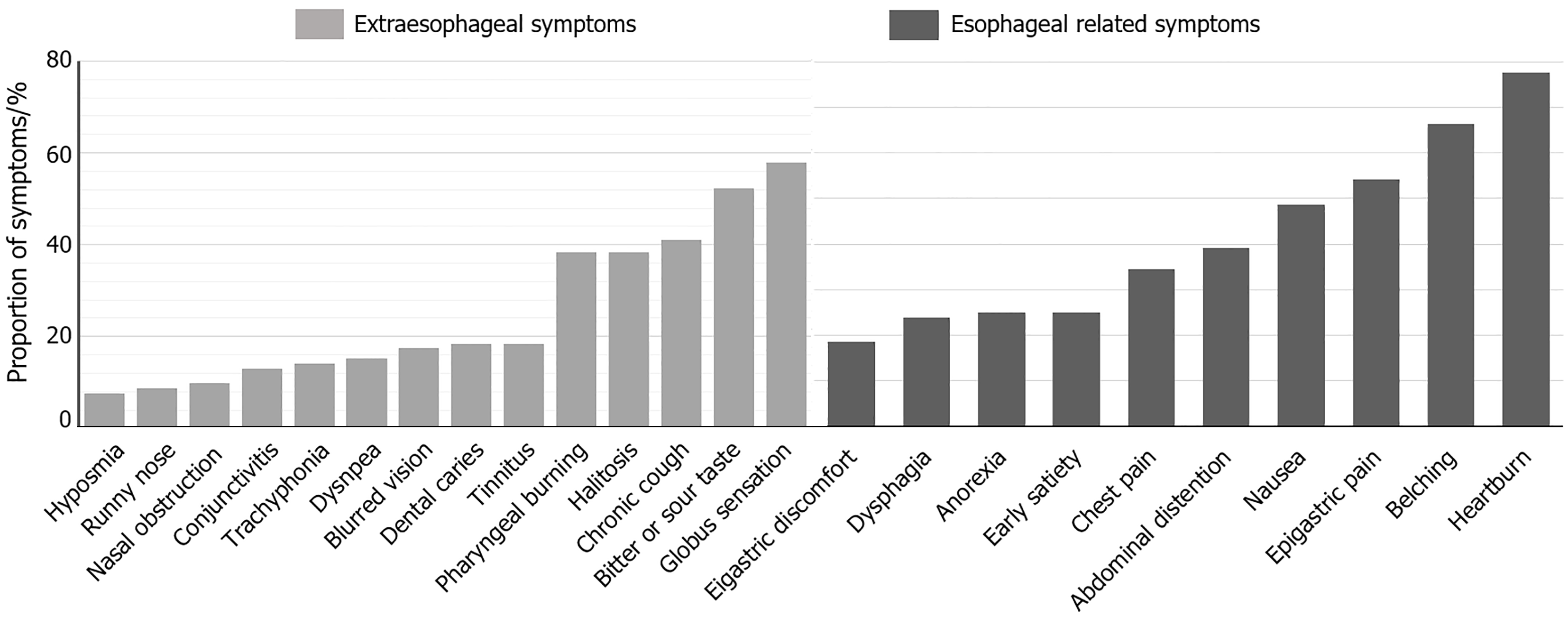

The study included 107 patients (43 males, 64 females; mean age 51.6 ± 13.1 years). The predominant esophageal symptom in RH patients was heartburn, impacting 77.57% of participants, succeeded by belching (66.36%), epigastric pain (54.21%), nausea (48.59%), abdominal distention (39.25%), and chest pain (34.58%). Notably, 94.39% of RH patients exhibited EES, with globus sensation (57.94%) and a bitter or sour taste (52.33%) being the most common manifestations. Additional symptoms comprised chronic cough (41.12%), halitosis (38.31%), and pharyngeal burning (38.31%) (Figure 2).

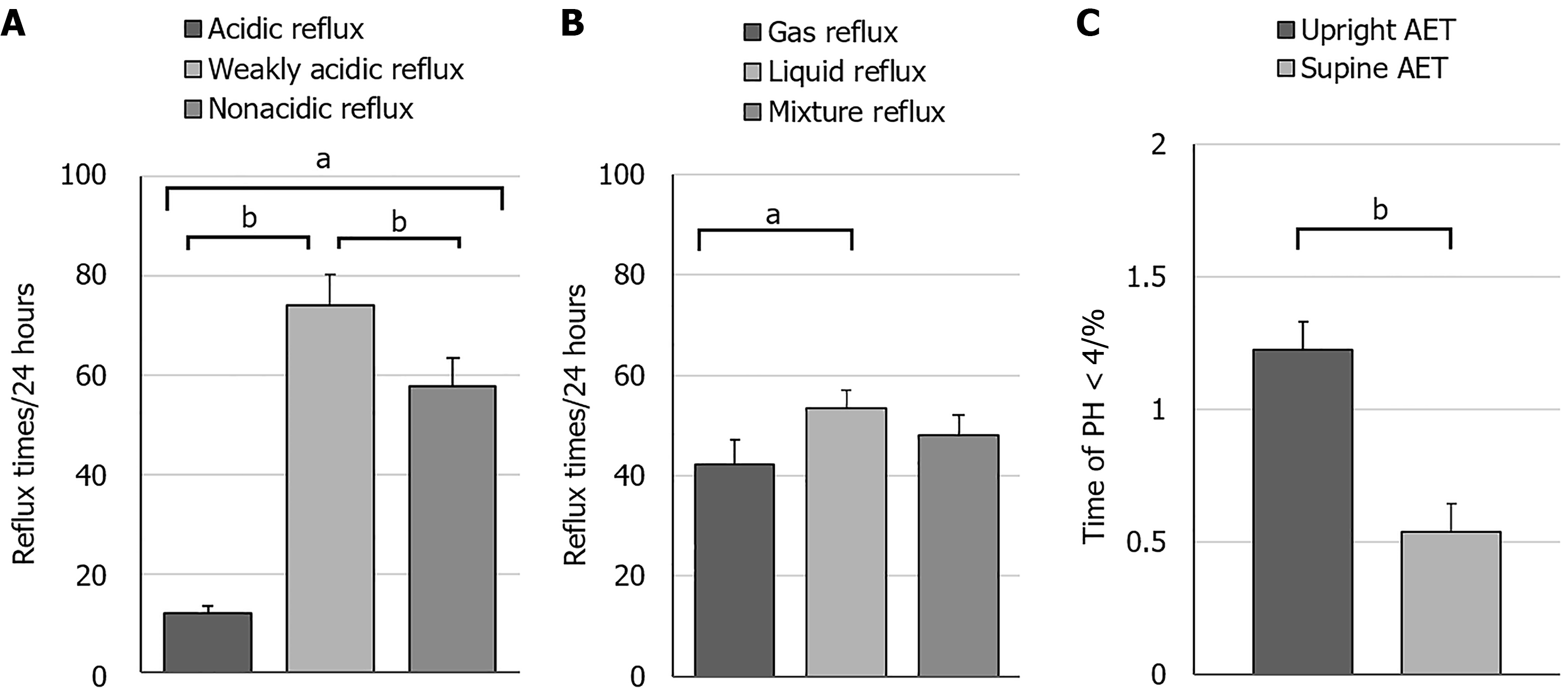

In RH patients, the incidence of WAR (74.10 times/24 hours) was markedly greater than that of AR (11.91 times/24 hours) and NAR (57.79 times/24 hours) (P < 0.0001) (Figure 3A). Liquid reflux events (53.51 times/24 hours) transpired significantly more frequently than pure gas reflux events (42.27 times/24 hours) (P < 0.05) (Figure 3B). The upright reflux time (1.22%) was significantly greater than the supine reflux time (0.54%) (P < 0.0001) (Figure 3C). Supplementary Table 1 presents parameters from 24-hour MII-pH monitoring and HRM in patients with RH.

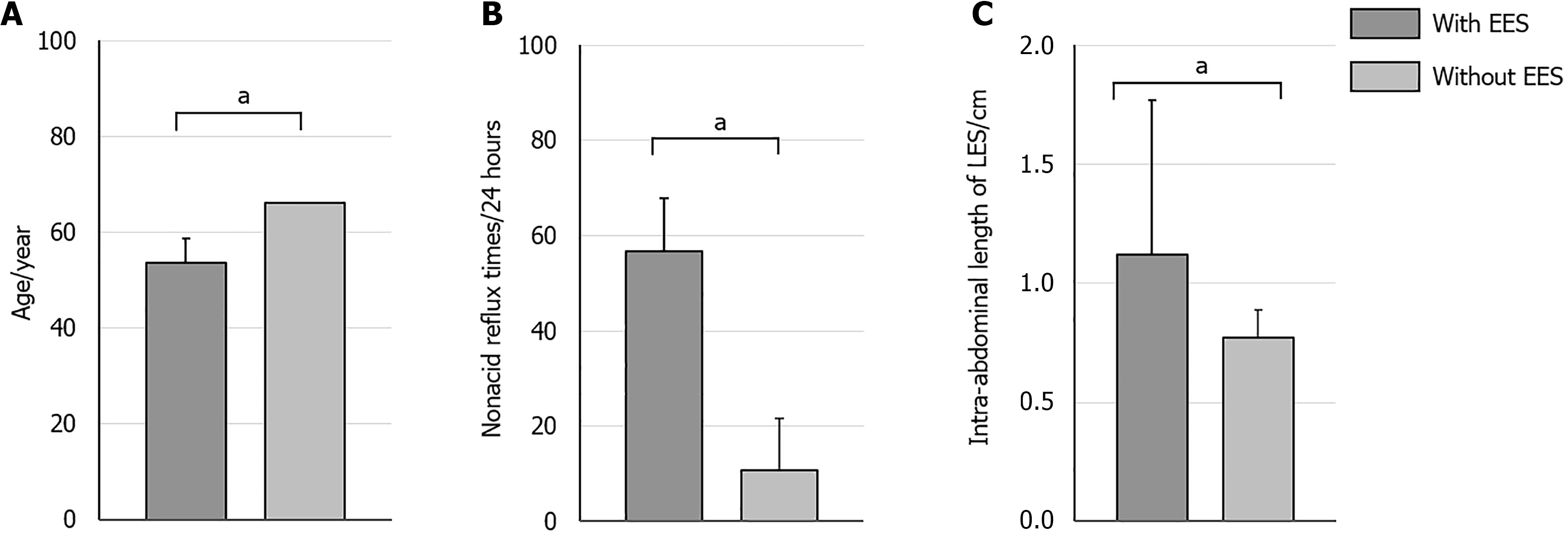

Patients with EES (n = 101) had a mean age of 53.56 years, significantly younger than those without EES (n = 6), whose mean age was 66.00 years (P < 0.05). Furthermore, they exhibited a markedly elevated incidence of NAR episodes (56.83 times/24 hours compared to 10.67 times/24 hours) and possessed a greater intra-abdominal length of the LES (1.12 cm vs 0.77 cm) (P < 0.05) (Figure 4). No significant differences were observed in gender distribution, BMI, and hiatal hernia between the two groups (P > 0.05).

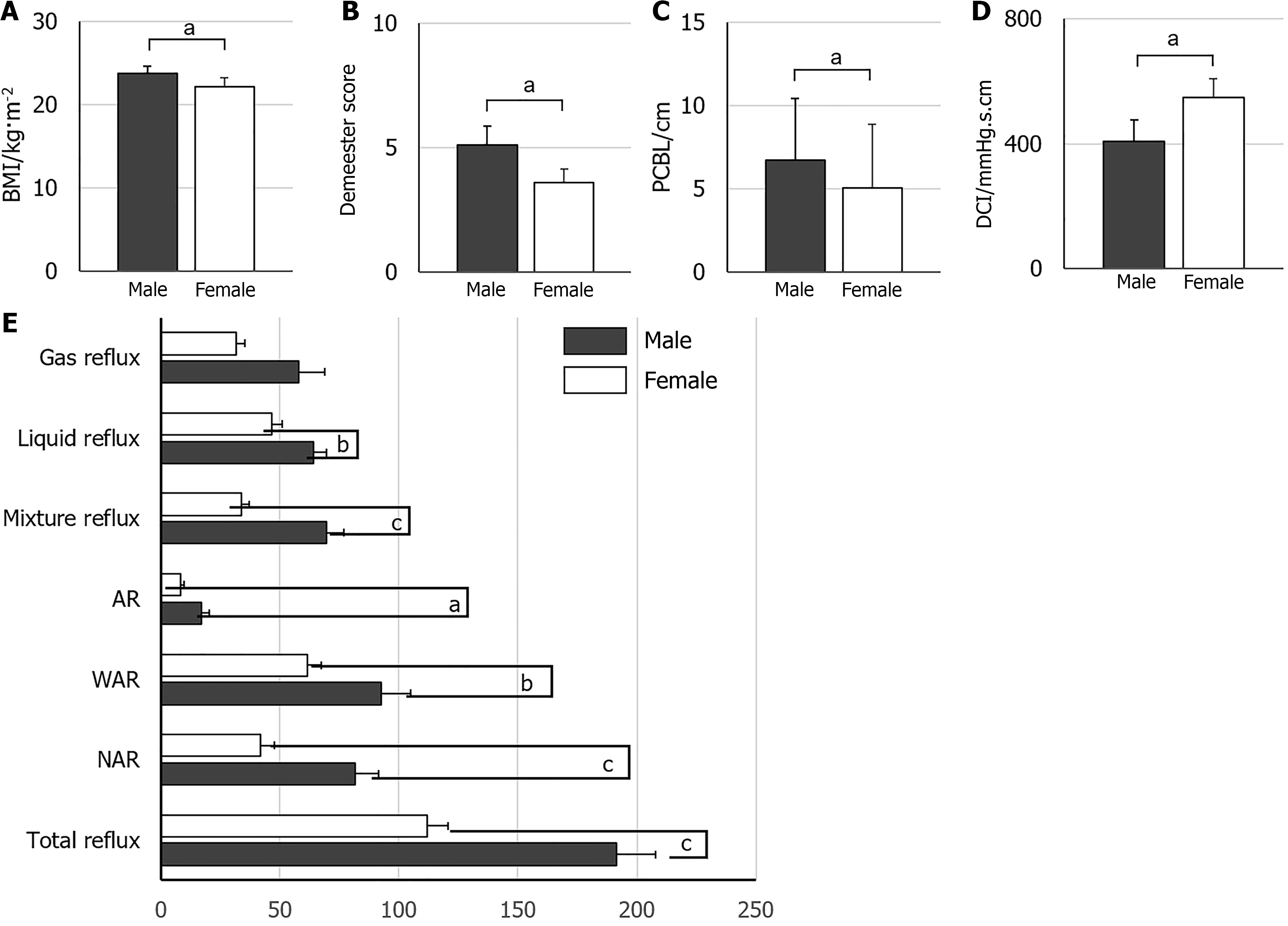

Male patients exhibited significantly increased frequencies of AR, WAR, and NAR compared to females, in addition to higher BMI, DeMeester scores, prolonged peristaltic contraction break length, and reduced distal contractile integral (P < 0.05). Peristaltic contraction break length denotes the mean duration of interruptions or pauses in the transmission of peristaltic waves during esophageal manometry, indicating the coordination and regularity of esophageal peristalsis. Distal contractile integral quantifies the contraction strength of the distal esophagus, extending from the transition zone to the upper boundary of the LES, utilizing an isobaric line of 20 mmHg. It is computed as esophageal contraction pressure multiplied by transit time and the length of the relevant esophageal segment being traversed (Figure 5). No substantial difference was observed between males and females concerning gas reflux frequency, upright reflux duration, or supine reflux duration (Table 1).

| Male (n = 43) | Female (n = 64) | P value | |

| Age, year (mean ± SD) | 51.37 ± 16.05 | 56.44 ± 10.42 | 0.168 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 23.36 ± 2.83 | 22.17 ± 3.02a | 0.041 |

| 24-hour MII-pH monitoring, median (IQR) | |||

| AR, times | 13.0 (17.0) | 6.0 (10.5)b | 0.003 |

| WAR, times | 71.0 (66.0) | 51.5 (54.0)a | 0.011 |

| NAR, times | 71.0 (64.0) | 23.5 (49.5)c | < 0.001 |

| Gas reflux, times | 32.0 (16.0, 65.0) | 23.0 (14.3, 40.0) | 0.054 |

| Liquid reflux, time | 59.0 (54.0) | 38.0 (40.0)b | 0.005 |

| Mixture reflux, times | 59.0 (60.0) | 29.5 (31.5)c | < 0.001 |

| DeMeester score | 3.5 (6.8) | 1.8 (4.6)a | 0.033 |

| High-resolution manometry, median (IQR) | |||

| Length of LES, cm | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.9) | 0.677 |

| IRP, mmHg | 2.88 (6.20) | 2.54 (3.36) | 0.694 |

| DCI, mmHg∙second∙cm | 231.0 (417.0) | 417.0 (619.3)a | 0.033 |

| DL, second | 6.8 (1.8) | 7.10 (1.8) | 0.654 |

| PCBL, cm | 6.9 (5.9) | 4.9 (5.1)a | 0.025 |

Relative to the control group, the RH group exhibited a greater age, a higher percentage of females, married individuals, and individuals with lower educational attainment (P < 0.05). Patients with RH exhibited a higher propensity for hiatal hernia, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), insomnia, anxiety, and depression (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that age (OR = 5.633), hiatal hernia (OR = 13.103), and anxiety (OR = 17.342) are independent risk factors for RH (Table 2).

| Variable | RH group (n = 92) | Control group (n = 104) | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| P value | OR | P value | |||

| Age, year (mean ± SD) | 51.6 ± 13.1 | 41.8 ± 13.6 | < 0.001 | ||

| Youth/middle age/elderly | 21/46/25 | 52/42/10 | < 0.001 | 5.633 | 0.030 |

| Gender (male/female) | 37/55 | 57/47 | 0.041 | 1.492 | 0.296 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 22.6 ± 2.8 | 23.2 ± 3.4 | 0.195 | ||

| Higher education (yes/no) | 27/65 | 62/42 | < 0.001 | 0.647 | 0.335 |

| Marriage (yes/no) | 86/6 | 81/23 | 0.002 | 0.921 | 0.904 |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Coronary disease (yes/no) | 5/87 | 1/103 | 0.162 | ||

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 16/76 | 15/89 | 0.57 | ||

| Diabetes (yes/no) | 2/90 | 3/101 | 0.753 | ||

| Hiatal hernia (yes/no) | 12/80 | 1/103 | 0.001 | 13.103 | 0.020 |

| IBS (yes/no) | 25/67 | 15/89 | 0.027 | 1.539 | 0.384 |

| Insomnia (yes/no) | 70/22 | 53/51 | < 0.001 | 2.572 | 0.053 |

| Anxiety (yes/perhaps/no) | 24/17/51 | 2/3/99 | < 0.001 | 17.342 | 0.000 |

| Depression (yes/perhaps/no) | 2/22/68 | 0/3/101 | < 0.001 | 0.598 | 0.613 |

The EES present in RH patients are as intricate as those linked to GERD. These symptoms may impact the ears, nose, throat, and eyes, indicating a possible involvement of laryngopharyngeal reflux in RH, contributing to a range of nonspecific symptom clusters. While existing evidence does not confirm a direct causal relationship, two potential explanations may elucidate these findings: (1) Although reflux in the RH remains within normal physiological limits, the mucosal barrier of extraesophageal tissues, including the larynx and bronchus, is considerably more susceptible to gastric acid and pepsin than the esophageal mucosa. These tissues may respond to even minimal levels of reflux stimulation[12]; and (2) The phenomenon of “distal reflux, proximal sensitization” warrants attention. Acid perfusion in the distal esophagus can elicit esophageal hypersensitivity, affecting not only the region directly exposed to acid but also the proximal esophagus adjacent to the laryngopharynx[13]. This reaction, possibly facilitated by central sensitization, may elucidate the occurrence of EES in RH patients[10]. RH is predominantly defined by WAR, a result corroborated by previous research[14]. Research conducted by Vela et al[15] in 2001 demonstrated that WAR may cause symptoms akin to those produced by AR. The efficacy of anti-reflux therapies, whether pharmacological or surgical, relies not solely on acid suppression but also on the proficient management of WAR[16].

Additionally, patients with EES demonstrated a greater incidence of NAR relative to those without EES, whereas no notable difference was found in the prevalence of AR or WAR. Prior research has shown that both WAR and NAR contribute to EES, especially those impacting the upper respiratory tract[17,18]. The mechanism of reflux perception may differ based on reflux pH, likely due to the specific pH thresholds necessary to activate acid-sensitive receptors[19]. The induction of EES by WAR or NAR indicates that, amidst the availability of various acid suppression therapies, we must remain attentive to the adverse effects of nonacid substances in reflux.

The duration of reflux in RH patients was markedly prolonged in the upright position compared to the supine position. Clinical studies on laryngopharyngeal reflux have similarly indicated that upright reflux occurs more frequently than supine reflux[20]. Studies on GERD have shown that patients who experience reflux solely in the upright position frequently exhibit normal DeMeester scores[21]. A potential explanation for this phenomenon is that these patients sustain an effective anti-reflux barrier while in the supine position. When adopting an upright posture, gastric air interacts with the LES. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure induces relaxation of the LES via stimulation of gastric stretch receptors, thereby promoting upright reflux events.

Significantly, patients with EES in this study were younger and possessed a longer LES segment within the abdominal cavity compared to those without EES. Prior studies demonstrate that advancing age correlates positively with heigh

Gender-based analyses indicated that male patients encountered a greater incidence of reflux episodes and demonstrated more significant esophageal motility disorders. These abnormalities presented as diminished distal esophageal contractility and uncoordinated esophageal peristalsis, indicating a heightened level of esophageal mucosal microinjury and motility dysfunction in males. Treatment strategies for male patients should emphasize mucosal prote

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that age is a significant risk factor for RH, with elderly individuals exhibiting a 5.633-fold increased risk compared to younger populations. This discovery corresponds with earlier studies on GERD[23], indicating that the onset of RH may be linked to age-related decline in the anti-reflux barrier. Although gender distribution was statistically significant in the univariate analysis, it lost significance in the multivariate model. An Italian study suggested that roughly 66.5% of RH patients were female, a ratio comparable to that found in our study[24]. Nonetheless, the extent to which female sex serves as an independent risk factor for RH necessitates additional research.

Furthermore, 48.2% of RH patients in this study exhibited a concurrent hiatal hernia, a recognized risk factor for GERD[2]. The findings indicate that while RH is categorized as a functional gastrointestinal disorder according to the Rome IV criteria, its pathophysiology may intersect with that of GERD, warranting additional investigation into this correlation[4]. Moreover, hiatal hernia has been recognized as a prognostic indicator of surgical treatment efficacy in RH patients[9].

This study revealed a significant correlation between RH and IBS, in addition to hiatal hernia. The incidence of IBS in the RH group (27.17%) was almost twice that of the control group (14.42%) (P < 0.05), aligning with prior research indicating a RH-IBS overlap rate of up to 48.2%[3]. This corroborates the hypothesis that RH and IBS may signify different manifestations of visceral hypersensitivity in various regions of the gastrointestinal tract[1,25]. The correlation between RH and insomnia necessitates additional scrutiny. While the causal relationship is ambiguous, our study indicated that sleep disturbances in RH approached statistical significance in multivariate analysis (P = 0.053). This discovery aligns with previous studies indicating a bidirectional association between RH and sleep disorders. Sawada et al’s review emphasizes the possible influence of sleep disturbances on increasing esophageal sensitivity, as evidenced by clinical data from GERD patients[26]. Our research offers further evidence through direct analysis of data from RH patients, supporting the hypothesis that RH and sleep disturbances may mutually reinforce each other in a “vicious cycle”, where RH diminishes sleep quality, subsequently intensifying esophageal sensitivity[27].

In addition, anxiety and depression were markedly more common in the RH group compared to the control group, with anxiety recognized as an independent risk factor for RH. This discovery supports previous studies highlighting the significance of psychological factors in functional esophageal disorders[28]. In healthy individuals, excessive stress can provoke temporary upper abdominal symptoms. In individuals with visceral hypersensitivity, these symptoms arise from heightened reactions to minor stressors that would not ordinarily elicit symptoms in healthy individuals. In RH patients, these symptoms are frequently chronic and persistent, likely attributable to brain-gut interactions that facilitate central sensitization and increased esophageal sensitivity[28]. Acute stress has been demonstrated to augment esophageal acid perception and diminish pain thresholds, even in the absence of esophageal inflammation. The magnitude of these responses is associated with a person’s emotional reaction to stress. Moreover, acute stress may result in the enlargement of the subepithelial space, enhancing esophageal mucosal permeability and allowing gastric acid to reach nociceptors[6,29]. Consequently, these findings highlight the significance of neuromodulatory therapies in the management of RH. Nonetheless, despite the increasing acknowledgment of the therapeutic potential of neuromodulators, current clinical practice predominantly relies on empirical evidence, as formal guidelines for their application in RH are still absent.

Our study highlights the intricate nature of RH, defined by the complex interaction of physiological, anatomical, and psychosocial elements. The results underscore the necessity of evaluating both acid and nonacid reflux, along with the influence of visceral hypersensitivity and central sensitization in symptom manifestation. The identified correlations with age, gender, body position, and psychological factors underscore the necessity for tailored and holistic management approaches.

| 1. | Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;S0016-5085(16)00223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1366] [Cited by in RCA: 1374] [Article Influence: 152.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Miwa H, Pandolfino JE, Zerbib F. Functional Esophageal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;S0016-5085(16)00178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yamasaki T, Fass R. Reflux Hypersensitivity: A New Functional Esophageal Disorder. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Bortoli N, Tolone S, Savarino EV. Weight Loss Is Truly Effective in Reducing Symptoms and Proton Pump Inhibitor Use in Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Price DD, Zhou Q, Moshiree B, Robinson ME, Verne GN. Peripheral and central contributions to hyperalgesia in irritable bowel syndrome. J Pain. 2006;7:529-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wong MW, Liu TT, Yi CH, Lei WY, Hung JS, Cock C, Omari T, Gyawali CP, Liang SW, Lin L, Chen CL. Oesophageal hypervigilance and visceral anxiety relate to reflux symptom severity and psychological distress but not to acid reflux parameters. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54:923-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut. 2005;54:449-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aggarwal P, Kamal AN. Reflux Hypersensitivity: How to Approach Diagnosis and Management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Patel A, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Prevalence, characteristics, and treatment outcomes of reflux hypersensitivity detected on pH-impedance monitoring. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1382-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Leech T, Peiris M. Mucosal neuroimmune mechanisms in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) pathogenesis. J Gastroenterol. 2024;59:165-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR, Bredenoord AJ, Prakash Gyawali C, Roman S, Babaei A, Mittal RK, Rommel N, Savarino E, Sifrim D, Smout A, Vaezi MF, Zerbib F, Akiyama J, Bhatia S, Bor S, Carlson DA, Chen JW, Cisternas D, Cock C, Coss-Adame E, de Bortoli N, Defilippi C, Fass R, Ghoshal UC, Gonlachanvit S, Hani A, Hebbard GS, Wook Jung K, Katz P, Katzka DA, Khan A, Kohn GP, Lazarescu A, Lengliner J, Mittal SK, Omari T, Park MI, Penagini R, Pohl D, Richter JE, Serra J, Sweis R, Tack J, Tatum RP, Tutuian R, Vela MF, Wong RK, Wu JC, Xiao Y, Pandolfino JE. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0(©). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33:e14058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 140.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Samuels TL, Handler E, Syring ML, Pajewski NM, Blumin JH, Kerschner JE, Johnston N. Mucin gene expression in human laryngeal epithelia: effect of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:688-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van den Elzen BD, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. Gastric hypersensitivity induced by oesophageal acid infusion in healthy volunteers. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:160-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Savarino E, Zentilin P, Tutuian R, Pohl D, Gemignani L, Malesci A, Savarino V. Impedance-pH reflux patterns can differentiate non-erosive reflux disease from functional heartburn patients. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:159-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vela MF, Camacho-Lobato L, Srinivasan R, Tutuian R, Katz PO, Castell DO. Simultaneous intraesophageal impedance and pH measurement of acid and nonacid gastroesophageal reflux: effect of omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1599-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Frazzoni M, Piccoli M, Conigliaro R, Frazzoni L, Melotti G. Laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14272-14279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 17. | Mims JW. The impact of extra-esophageal reflux upon diseases of the upper respiratory tract. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:242-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Saniasiaya J, Kulasegarah J. The link between airway reflux and non-acid reflux in children: a review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;89:329-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kawami N, Hoshino S, Hoshikawa Y, Tanabe T, Koeda M, Momma E, Takenouchi N, Hanada Y, Kaise M, Iwakiri K. Determinants of reflux perception in patients with non-erosive reflux disease who have reflux-related symptoms on potassium-competitive acid blocker therapy. Esophagus. 2022;19:367-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mesallam TA, Baqays AA. Characteristics of upright versus supine reflux pattern in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;87:200-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hoppo T, Komatsu Y, Nieponice A, Schrenker J, Jobe BA. Toward an improved understanding of isolated upright reflux: positional effects on the lower esophageal sphincter in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. World J Surg. 2012;36:1623-1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Masuda T, Mittal SK, Kovacs B, Csucska M, Bremner RM. Simple Manometric Index for Comprehensive Esophagogastric Junction Barrier Competency Against Gastroesophageal Reflux. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:744-755e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Becher A, Dent J. Systematic review: ageing and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms, oesophageal function and reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:442-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | de Bortoli N, Frazzoni L, Savarino EV, Frazzoni M, Martinucci I, Jania A, Tolone S, Scagliarini M, Bellini M, Marabotto E, Furnari M, Bodini G, Russo S, Bertani L, Natali V, Fuccio L, Savarino V, Blandizzi C, Marchi S. Functional Heartburn Overlaps With Irritable Bowel Syndrome More Often than GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1711-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What Is New in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:151-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sawada A, Sifrim D, Fujiwara Y. Esophageal Reflux Hypersensitivity: A Comprehensive Review. Gut Liver. 2023;17:831-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Elkalawy H, Abosena W, Elnagger M, Allison H. Wake up to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: The interplay between arousal and night-time reflux. J Sleep Res. 2024;33:e14158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Losa M, Manz SM, Schindler V, Savarino E, Pohl D. Increased visceral sensitivity, elevated anxiety, and depression levels in patients with functional esophageal disorders and non-erosive reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33:e14177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Farré R, De Vos R, Geboes K, Verbecke K, Vanden Berghe P, Depoortere I, Blondeau K, Tack J, Sifrim D. Critical role of stress in increased oesophageal mucosa permeability and dilated intercellular spaces. Gut. 2007;56:1191-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |