Published online Jan 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i1.98479

Revised: October 26, 2024

Accepted: November 11, 2024

Published online: January 7, 2025

Processing time: 165 Days and 6.8 Hours

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) poses a substantial global health challenge, with prevalence rates exhibiting geographical variation. Despite its widespread recognition, the exact prevalence and associated risk factors remain elusive. This article comprehensively analyzed the global burden of GERD, shed

Core Tip: To enhance physicians' understanding of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), it is crucial to comprehensively examine its risk factors, underlying pathophy

- Citation: Wickramasinghe N, Devanarayana NM. Unveiling the intricacies: Insight into gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(1): 98479

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i1/98479.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i1.98479

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is defined as the effortless passage of gastric contents into the esophagus, and it is a normal physiological process. According to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines, when GER leads to troublesome symptoms such as frequent heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, burping, cough, dysphagia, or complications such as esophagitis or stricture formation, it is referred to as GER disease (GERD)[1,2].

The global prevalence of GERD, despite its widespread discussion, remains uncertain due to several factors. Chief among these is the absence of a universally accepted definition of GERD. The gold standard for diagnosing GERD is combined pH impedance testing, which is invasive and often not widely available, posing challenges for widespread use in epidemiological studies. Procedures like endoscopy and multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH monitoring are labor-intensive and impractical for determining community prevalence. Although endoscopy is more commonly used than ambulatory pH tests, it cannot detect non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), further complicating accurate prevalence estimation. Consequently, various symptom questionnaires and definitions have been utilized as screening tools in much of the research on GERD epidemiology, leading to wide variation in prevalence estimates.

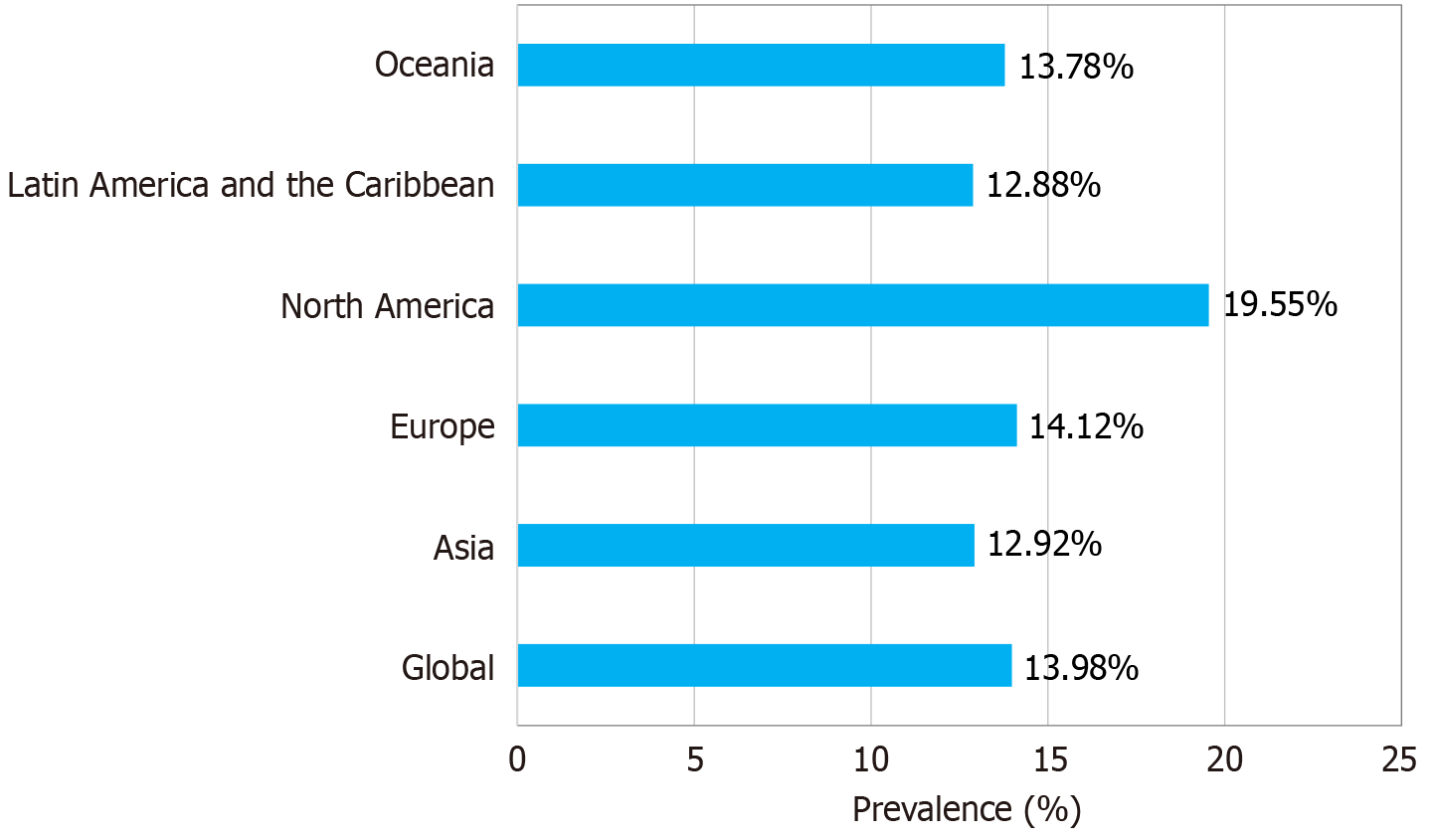

After reviewing research around the globe, many experts have employed heartburn and/or regurgitation occurring at least once a week as a threshold for GERD[3,4]. Nirwan et al[3] conducted the most recent systematic review and meta-analysis on GERD in 2020[3]. “Having heartburn and/or regurgitation at least once weekly” was the definition that was applied. However, this definition overlooks a significant portion of patients with GERD who may be asymptomatic or present with symptoms other than reflux or heartburn. It also fails to distinguish between gastrointestinal disorders like reflux hypersensitivity and functional heartburn, which can manifest with similar symptoms. Figure 1 looks at the pooled prevalence of GERD according to geographical location based on data from Nirwan et al[3].

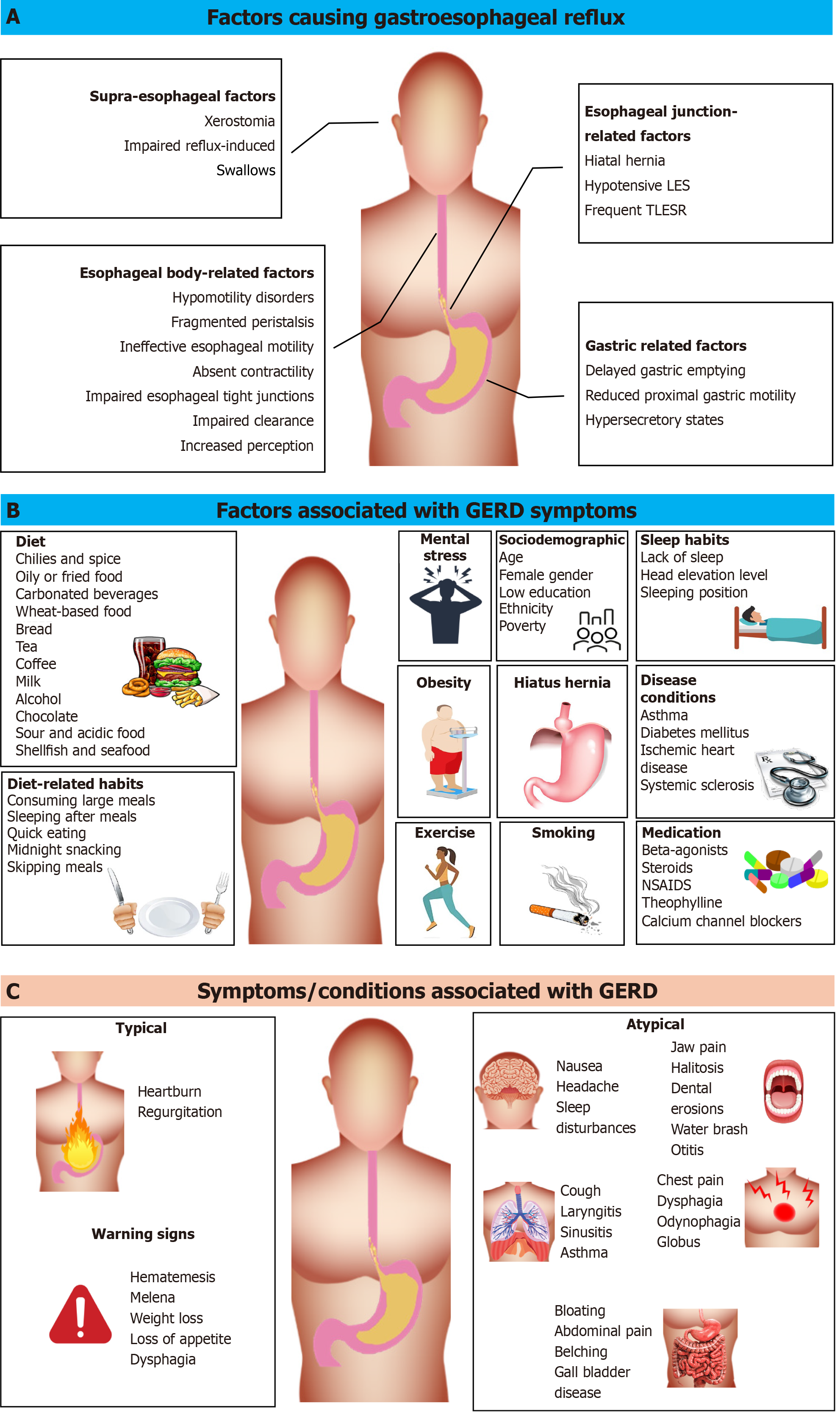

The pathophysiology of GERD is complex as it is a multifactorial disease condition with many genetic and environmental risk factors[5]. Underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of GERD are many[6]. According to Herregods et al[7], certain factors can either cause or worsen GER, while other factors may amplify the severity of GERD symptoms[7]. According to Miller et al[8] and Nandurkar and Talley[9], the main causes of increased GER include transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) and other irregularities in lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure[8,9]. Figure 2A summarizes the pathophysiological factors causing GERD.

Motor abnormalities and anatomical factors implicated in the pathogenesis of GERD are believed to have a genetic basis, supported by studies showing approximately 31% heritability of GERD. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes such as FOXF1, CCND1, MHC, DNA repair genes, and specific genetic loci on chromosomes 3, 15, and 19, among others, have been identified[10]. Additionally, genes like CRTC1, BARX1, and FOXP1, are identified as susceptibility loci associated with the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus (BE)[10-12].

Overall, GERD is said to be caused by a malfunctioning LES triggered by risk factors such as obesity, smoking, family history, pregnancy, hiatus hernia, reduced gastric motility, and medications[12-17]. Figure 2B summarizes the recognized risk factors/associated factors of GERD.

GERD can result in erosive reflux disease or NERD. When reflux induces inflammation or ulceration of the esophagus, it is defined as erosive reflux disease. Meanwhile, patients whose endoscopy does not show erosive changes but still produces abnormal acid reflux on 24-hour pH monitoring recordings are labeled as having NERD. NERD is the most common presentation of GERD, with around 78%-93% of all reflux diseases being labelled as NERD in the Asia-Pacific region[18]. There is another subset of patients with reflux sensitivity who have GER within the normal range but in whom esophageal hypersensitivity results in the generation of symptoms[19]. The main differential diagnosis for GERD is functional heartburn, which presents with similar symptoms, but there is no evidence of either increased GER on ambulatory pH monitoring or esophageal mucosal damage on endoscopy[20].

GERD is among the most prevalent gastrointestinal motility disorders affecting individuals of all ages and is characterized by a range of uncomfortable symptoms, including chest pain, heartburn, sour taste in the mouth, bad breath (halitosis), vomiting, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), and respiratory issues[1]. The common GERD symptoms are shown in Figure 2C.

GERD leads to a range of complications such as reflux esophagitis, BE, strictures, and extra-esophageal manifestations, such as asthma, chronic cough, and laryngitis[21,22].

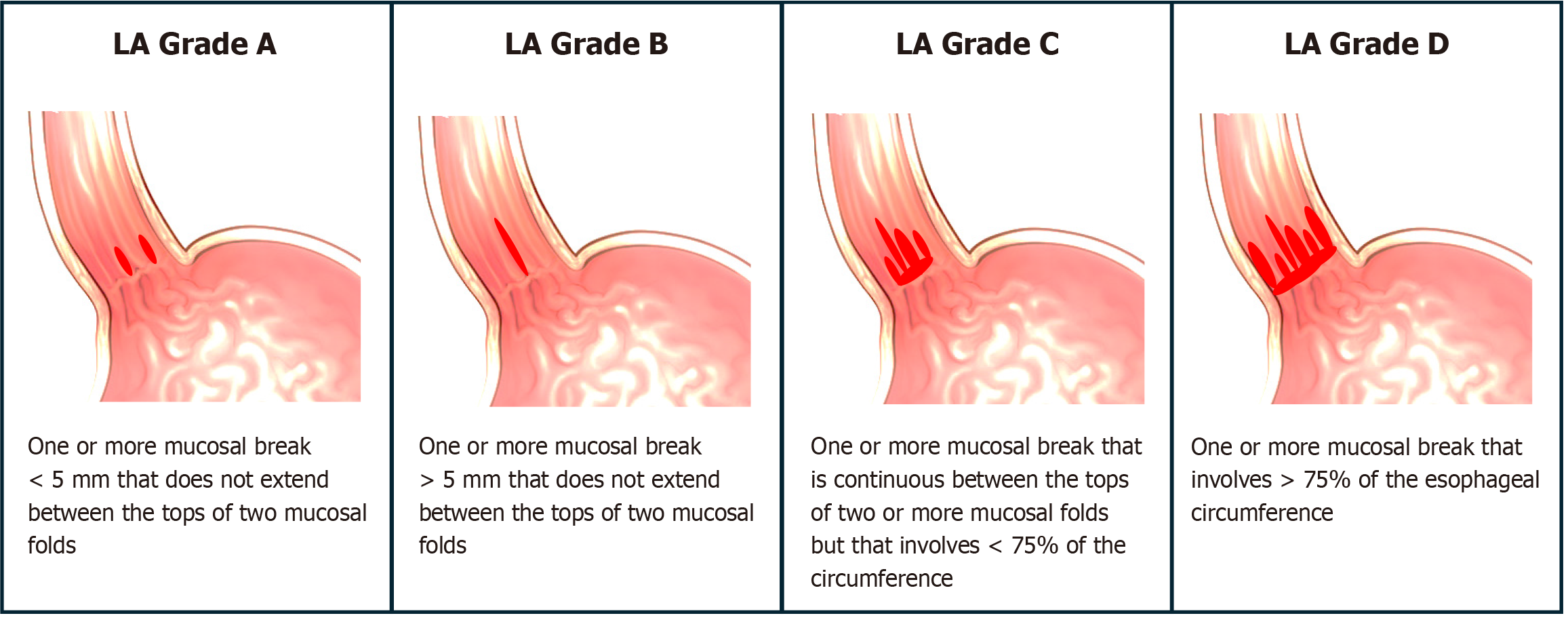

Reflux esophagitis, characterized by inflammation of the esophageal mucosa and encountered by gastroenterologists during endoscopy, is the most common complication of GERD[23]. According to the Los Angeles classification system as seen in Figure 3, reflux esophagitis is graded into Grades A, B, C, and D based on endoscopic findings[24]. Of them, only Grades C and D are considered diagnostic of GERD[25].

BE is characterized by the transformation of the normal stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus into a metaplastic columnar epithelium. Diagnosis of BE requires the presence of columnar epithelium extending more than 1 cm proximal to the gastroesophageal junction, confirmed by biopsy[26]. BE is of concern because it can progress from metaplastic epithelium to dysplasia and potentially to carcinoma[26].

An esophageal stricture or narrowing of the esophageal lumen can occur in GERD due to acid-induced mucosal damage, chronic inflammatory changes, fibrosis, scarring, and loss of distensibility. Patients with esophageal strictures commonly present with dysphagia[27].

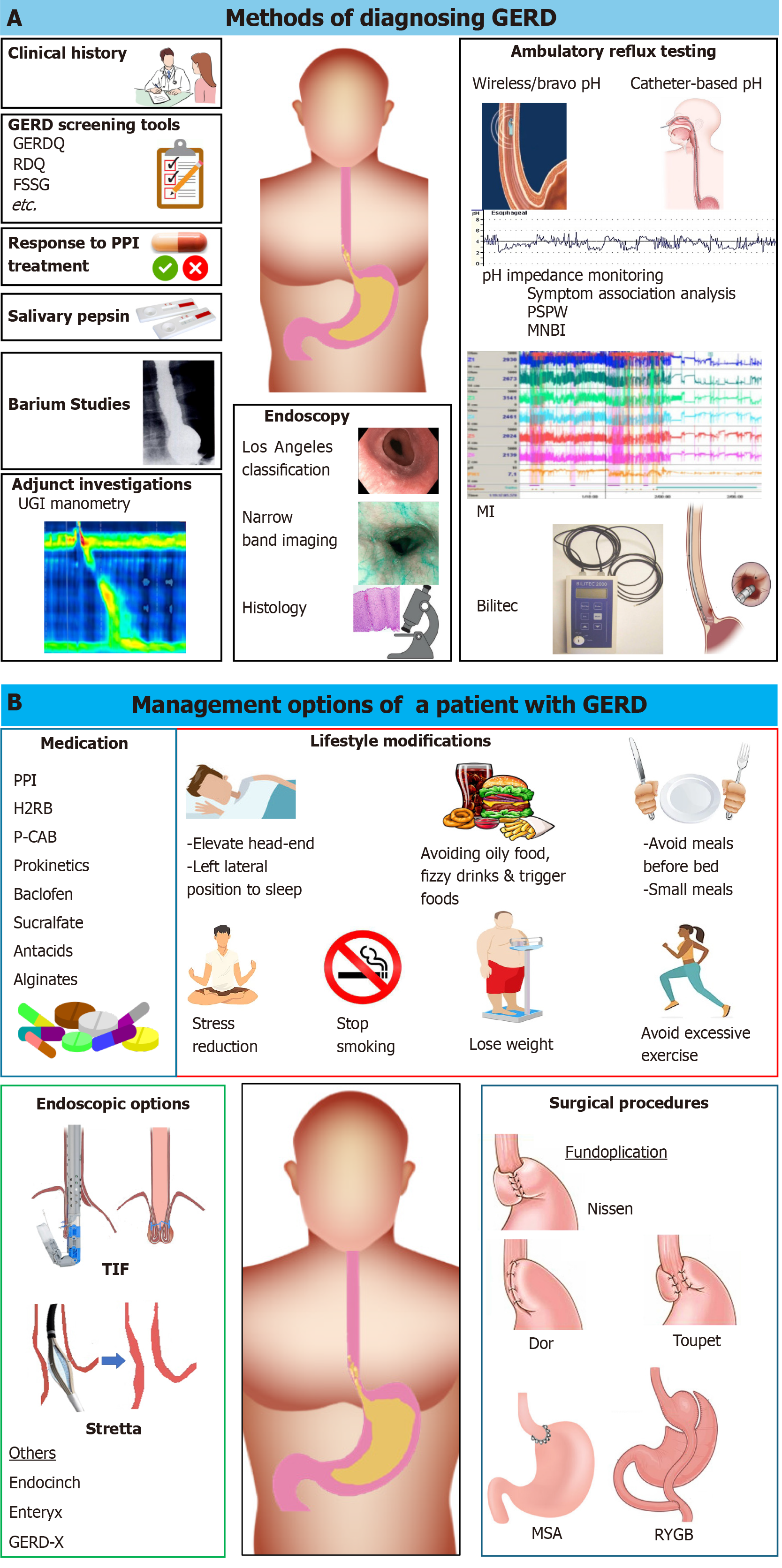

The diagnosis of GERD is usually symptom-based, but certain investigations, such as esophageal-gastro-duodenoscopy and ambulatory esophageal pH impedance monitoring, are useful in confirming the diagnosis[2]. Figure 4A summarizes the various diagnostic methods used in the management of GERD.

Symptom-based diagnosis can be optimized by using validated, country-specific GERD screening tools with credible sensitivities and specificities. Many countries have validated country-specific symptom-based screening tools with high sensitivity and specificity, which can be applied to diagnose GERD in community settings[28].

The investigations most useful to confirm the diagnosis of GERD are upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy and 24-h ambulatory combined pH impedance studies. Twenty-four-hour pH-metry and pH capsules have not shown significant diagnostic value in GERD. Other investigations performed to exclude common differential diagnoses include barium contrast studies, high-resolution manometry, endoluminal functional lumen imaging probe and gastric scintigraphy[29].

UGI endoscopy is useful in identifying erosive esophagitis and its complications[24]. Endoscopy has a limitation since patients with NERD do not have visible lesions. If there are visible mucosal lesions, a biopsy can help differentiate erosive esophagitis and BE from eosinophilic esophagitis and carcinoma, which are not directly related to GERD[30].

Intraluminal impedance, combined with pH monitoring, enables the identification of retrograde bolus movement and provides detailed information about reflux events, including their frequency, duration, acidic nature, and relationship with symptoms. Thus, when recorded for 24 h, it is helpful to quantify the GER and detect its association with symptoms. Therefore, pH impedance is more sensitive and specific in confirming the diagnosis of GERD[31]. It is also useful in differentiating NERD from functional heartburn and reflux hypersensitivity. Without the combination of impedance, isolated pH monitoring is not useful in diagnosing GERD, especially in the pediatric age group and those on regular acid-lowering drugs[30,32].

Gastrointestinal motility studies are not commonly performed as first-line investigations in patients with GERD. However, high-resolution manometry is useful in diagnosing hiatus hernia and ruling out esophageal motor disorders such as achalasia[33]. This technology utilizes multiple closely spaced sensors to measure intraluminal pressure along the entire length of the esophagus.

Delayed gastric emptying is a recognized pathophysiological mechanism of GERD. Gastric emptying studies are sometimes recommended in treatment-refractory GERD to identify gastroparesis, which may benefit from prokinetic medications[34].

Management of GERD includes lifestyle modifications/non-pharmacological treatment, medical treatment, and surgical/endoscopic interventions[35]. Figure 4B summarizes these arms.

Habit modifications: As large meals[36], sleeping soon after eating a meal[37], eating a meal fast[38], midnight snacking[39], irregular mealtimes[39], and smoking[40] are recognized risk factors for GERD, it might be prudent to modify these or avoid these habits[41].

Positioning: Many trials have been done demonstrating that elevation of the head end of the bed improves GERD symptoms[42,43]. A systematic review done in 2006 showed the same[44]. However, a recent systematic review conduc

Sleeping in the left lateral position is recommended for patients with GERD because it reduces acid reflux. This position is believed to be effective because it positions the esophagogastric junction above the level of gastric juice[46]. The right lateral position, meanwhile, predisposes to reflux, as shown by experiments with prolonged acid exposure times and acid clearance durations[46,47].

A study conducted by Kapur et al[48] on 15 patients with GERD revealed no significant difference in TLESRs and LES pressure between the left and right lateral sleeping positions. However, they observed that postprandial reflux occurred twice as frequently in the right lateral position[48]. In a trial led by Allampati et al[49], a positional therapy device designed to position subjects in a left lateral sleeping position with head elevation was found to improve nocturnal GERD symptoms[49].

Dietary interventions: (1) Avoidance of the trigger food: While patients often avoid foods that trigger GERD symptoms and receive advice from medical professionals to do so, further studies are needed to better understand the role of dietary modifications in managing GERD[50,51]. Common trigger foods of GERD are listed in Figure 2B, and they include common culprits such as spices[52], fried food[53], carbonated beverages[54], bread[55], tea[56], coffee[57], acidic food[58], alcohol[59], and chocolate[60];

(2) Low-fat diet: Oily food is a common culprit for heartburn, with a significant association found between high fat intake and symptoms of GERD[53]. Of 32.8% of Sri Lankans were found to suffer from heartburn following the consum

A randomized control study not included in the review, which analyzed the symptoms of GERD in patients with metabolic syndrome, comparing a diet of low-fat vs full-fat dairy food, did not note a difference[66]. Meanwhile, another cross-sectional study not included in the systematic review analysis showed that it was not the amount of fat, but the type (higher saturated-to-unsaturated fat intake) that was associated with higher acid exposure time (AET) and number of reflux episodes[67];

(3) Low carbohydrate diet: The same systematic review in 2024 also analyzed the findings of studies on the effect of three studies[67-69] that demonstrated reduced GERD symptoms and distal esophageal acid exposure following low-carbohydrate diets[64]. One of these studies, a cross-sectional study analyzing objective and subjective GERD testing, noted that it is the type and not the amount of carbohydrate e.g., simple sugars, that was associated with GERD[67];

(4) Low fermentable, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet: A randomized controlled trial involving 8 patients with GERD symptoms compared the acute effects of a low FODMAP diet vs a high FODMAP diet, revealing reduced symptoms of regurgitation after meals with the low FODMAP diet. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to explore this area more comprehensively[70]; and

(5) Probiotics and prebiotics: Probiotics or live microorganisms administered for health benefits for humans are also thought to alleviate GERD symptoms. Analyzing 14 studies assessing the health effects of probiotics in patients with GERD, a systematic review (2020) reported that 11 (79%) of the studies had positive benefits. However, due to significant heterogeneity among the studies and the fact that only five of them were of good quality, quantitative evaluation of the results was not feasible[71].

Meanwhile, studies on prebiotics are quite rare, with only a case series suggesting that a soluble fiber named maltosyl-isomaltooligosaccharide might have an improvement of GERD symptoms[72].

Weight loss: Obesity is one of the strongest predictors of GERD. A significant association has been reported between body mass index, waist circumference, weight gain, and GERD symptoms and complications[73-76].

The underlying pathophysiology mechanisms of obesity-induced GERD are multifactorial and include increased intragastric pressure, increased TLESRs, esophageal dysmotility, hiatal hernia, and reduced LES tone[76]. Weight loss has been consistently shown to be a beneficial lifestyle modification across multiple studies[77,78].

Since the association between obesity and GERD is so strong, ACG guidelines recommend weight loss as part of the management of GERD[35]. The HUNT study also showed that a decrease in body mass index had a dose-dependent effect on reducing GERD symptoms[77].

Mental stress and other psychological/psychiatric conditions are important and well-recognized risk factors for developing symptoms of GERD[13,79]. These conditions could also lower the effectiveness of pharmacological and surgical therapies[80]. Mental stress is a recognized etiological factor for functional disorders such as functional dyspepsia and functional heartburn, which are major differential diagnoses of GERD as well as potential sources for treatment resistance[81]. Thus, stress relief could play an important role in the management of GERD[82].

Some interventions such as hypnotherapy, mindfulness training, relaxation techniques, biofeedback, breathing exercises, cognitive behavior therapy, and drugs such as anxiolytics can be considered in the treatment of GERD despite varying levels of evidence[83-86].

Hypnotherapy: Hypnotherapy is an established intervention for symptoms of functional gastrointestinal disorders[87,88]. This can be helpful in the management of GERD symptoms as functional heartburn is one of the main differential diagnoses of GERD and can coexist with GERD[20]. Hypnotherapy promotes a state of relaxation with focused attention targeted at reducing visceral hypersensitivity and symptom hypervigilance[88].

Mindfulness training: Psychological comorbidities increase GERD symptoms[89]. Interventional studies on patients with GERD symptoms have shown that anxiety, depression, and associated GERD symptoms reduce with mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques[85].

Relaxation: Similarly, a controlled study showed that patients who received relaxation training had significantly lower reflux symptom numbers and a reduced AET than those receiving a placebo[90].

Breathing exercises: The main goal of breathing exercises/respiratory physiotherapy is to improve diaphragmatic function and change the breathing pattern from thoracic to abdominal breathing pattern, which is ideal[91].

A systematic review was done in 2023 on 11 studies conducting breathing training. While the results were inconclusive due to the heterogenicity of different studies, the review noted that breathing does have a potential benefit and needs to be studied further[92]. A similar sentiment was expressed in a review conducted in 2020[93].

Cognitive behavior therapy: Cognitive behavior therapy focuses on recognizing GERD symptoms and warning signs and conducting behavioral exercises to prevent them. It is more in line with belching-associated reflux and is shown to reduce esophageal acid exposure in patients with GERD symptoms associated with supra gastric belching[94].

Biofeedback: Reflux and its symptoms are said to occur due to abdominal muscle contractions during gastroesophageal pressure equilibration. Biofeedback therapy involves relaxing these abdominal muscles and thus decreasing reflux[95]. A case-control study investigating the effectiveness of diaphragm biofeedback training in patients noted that crural diaphragm tension and gastroesophageal junction pressure, but not LES pressure, were significantly elevated following treatment. Acid suppression usage decreased significantly compared to controls[96]. Meanwhile, yet another study analyzing esophageal manometry testing following biofeedback sessions in a single subject showed that even LES pressure increased after the sessions, reducing symptomatic reflux episodes[97].

Anxiolytics: Anxiety and depression are psychological factors found at higher levels in subjects with GERD symptoms than in controls[98]. A systematic review conducted in 2015 showed that antidepressants help modulate esophageal sensation and can reduce functional chest pain[86].

Pain modulators such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in low doses are used for the management of functional heartburn, though some may have limited data regarding efficacy[86,99]. While patients with reflux hypersensitivity might benefit from medical treatment given for GERD due to esophageal hypersensitivity, the functional nature of the disease warrants the use of tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as the cornerstones of treatment[81].

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the most prescribed first-line drug for GERD. Other drugs prescribed are histamine receptor antagonists, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonists (e.g., baclofen), and potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CAB) (e.g., soraprazan, linaprazan)[35,100,101].

PPIs: PPIs irreversibly inhibit the H+/K+ adenosine triphosphatase pump (proton pump) of the parietal cell and are superior in reducing the secretion of gastric acid compared to H2 receptor blockers[102,103]. PPIs are not only the most prescribed drug for GERD but are also frequently overused[104]. While there are several types of PPIs available with varying degrees of acid suppression potency[105], meta-analyses have indicated that their effectiveness in healing and relieving symptoms differs only marginally[106].

Patients are advised to take PPIs 30 to 60 minutes before a meal because these medications bind specifically to active acid-secreting proton pumps[35]. PPIs, which cause significant acid suppression, are noted to be better at controlling typical GERD symptoms, such as heartburn, than other symptoms[107]. Previously, it was thought that patients with ERD responded better to PPIs than patients with NERD, but a new meta-analysis has shown that they are equally effective in both ERD and well-defined NERD[108]. A full-dose PPI therapy of 4 weeks to 8 weeks is recommended in patients with GERD symptoms[109]. If the response is not satisfactory with once-daily dosing, PPIs can be taken twice daily[110]. Patients not responding to PPIs should be investigated further[110]. If the symptoms recur after a satisfactory initial treatment, PPIs should be restarted at the lowest possible dose to control symptoms and can also be used on a need-to-use basis if there is no endoscopic evidence of GERD[35,109].

Those with endoscopic evidence of GERD, such as esophagitis, BE, and strictures, are advised to be on long-term PPI therapy to promote healing[35,109]. PPIs can be switched or a higher dose can be given if esophagitis is not healing satisfactorily[109]. While there are side effects of PPIs, experts agree that the benefits outweigh the risks[35]. Switching between classes of PPIs can be considered for those who experience minor side effects[35].

Long-term use of PPI is reported to be associated with multiple rare and devastating complications. They include nutritional deficiencies (e.g., calcium deficiency and risk of fracture and vitamin B12 deficiency)[111,112], increased risk of infection (e.g., Clostridioides difficile and respiratory infections)[113,114], kidney disease (e.g., acute intestinal nephritis and chronic kidney disease)[115,116], gastrointestinal problems (e.g., small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, rebound acid hypersecretion on discontinuation, increased risk of gastric cancer)[117-119], cardiovascular problems (e.g., impairing effectiveness of certain cardiovascular medications)[120], and cognitive decline (e.g., increased risk of dementia)[121]. However, despite theoretical concerns regarding the potential consequences, there is no current recommendation to initiate long-term PPI therapy with calcium, vitamin D, or vitamin B12 supplementation or routine monitoring of mineral density, serum B12 levels, magnesium levels, or creatinine levels[35].

Histamine 2 receptor blockers: Though histamine 2 receptor blockers (H2RB) are less potent at blocking gastric acid secretion[122], they are recommended in controlling nocturnal GERD symptoms[35]. While the NICE guidelines recommend administering H2RBs if the PPI response is inadequate[109], the ACG guidelines have no such recommen

P-CAB: P-CABs, like vonoprazan, are a relatively new class of drugs used in some Asian countries for GERD treatment[125]. They reversibly bind to the H+/K+ adenosine triphosphatase pumps and offer several advantages over PPIs, including rapid onset of action, longer half-life, and the ability to be taken independently of meals[100]. In a preliminary trial, P-CAB has shown a higher therapeutic benefit than PPIs in the management of GERD[125]. Given these advantages over PPIs, P-CABs are likely to become more commonly used for GERD treatment globally once they are established.

Prokinetics: Prokinetics that increase gastric motility reduce GER by improving gastric emptying and reducing intragastric pressure. Several systematic reviews on the role of prokinetic drugs in the treatment of GERD revealed that the pooled estimates of symptom resolution and endoscopic healing are better in patients on prokinetic agents[126,127]. However, they did not give conclusive evidence on which oral prokinetic agent is superior. Due to their central nervous system side effects, prokinetics such as metoclopramide and domperidone are not recommended solely for the use of GERD, except when delayed gastric emptying has been proven[35].

Baclofen: GABA class B receptors are found in the neurons of the motor nucleus of the vagus and nucleus tract solitarious and play an important role in TLESRs[101]. Thus, baclofen, a GABA-B agonist, is efficacious in reducing TLESRs, reflux episodes, and related symptoms. It can be used as a treatment for PPI-refractory, proven GERD. However, caution should be used due to side effects such as drowsiness and dizziness[35,128].

Sucralfate: Sucralfate binds to both normal and eroded mucosa by forming polyvalent bridges between positively charged proteins found in the mucosa (present in high concentrations in mucosal lesions) and the negatively charged sucralfate polyanions[129]. However, due to its limited documented efficacy in GERD, it is not recommended for the use of treatment for GERD except when pregnant[35].

Antacids: Antacids, composed of magnesium, calcium, aluminum, sodium, or combinations thereof, are generally well tolerated and can alleviate heartburn symptoms effectively. However, their efficacy in treating non-acid reflux and regurgitation is limited, making them primarily useful for symptom relief. Antacids are used exclusively for on-demand symptom relief, with little evidence to favor one type over another[35,110].

Alginates: Alginates or alginic acid derivatives precipitate into a gel-raft-like layer in the presence of gastric acid, creating a mechanical barrier and displacing the postprandial acid pockets[130]. According to a recent meta-analysis, alginates show higher effectiveness than antacids and placebos[131].

Criteria for those who warrant anti-reflux surgery are listed in Table 1[110]. The surgical options are discussed below.

| Criteria[110] |

| Having typical GERD symptoms; at least a year-long history |

| Response to PPI; need for PPI dosage to increase |

| Hiatal hernia |

| Documented esophagitis |

| Documented acid reflux |

| Documented symptom reflux correlation |

| Proven LES incompetence |

Anti-reflux surgery is intended to create a functional anti-reflux barrier. The fundoplication strengthens the LES, regains the normal anatomy through a crural repair, and reinstates the needed intra-abdominal esophagus length[110]. Fundoplication can be performed via open surgery, laparoscopy, or robotic-assisted surgery. Since its introduction in 1991, laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery has almost replaced open surgery and is now the standard approach for fundoplication[132]. Fundoplication can be “complete”, or it can have various stages of “partial fundoplication”, as subsequently demonstrated by Toupet, Belsey, Dor, Hill, and Collis[133].

Fundoplication, which creates a comprehensive barrier against both acidic and non-acidic reflux, demonstrates superior efficacy compared to PPIs in terms of reducing acid exposure time and improving symptoms. However, the procedure can be associated with surgical complications and occasional recurrence of symptoms in some patients[134,135]. Though a considerable number of patients require pharmacotherapy even after anti-reflux surgery, the patient satisfaction rates are significantly higher, and heartburn and regurgitation are lower compared to those under PPI treatment only[136]. When compared, both complete and partial fundoplication have similar efficacy, though each can give rise to complications such as dysphagia, bloating, and vomiting. The inability to belch is a complication of complete fundoplication, while a higher incidence of GERD recurrence is seen in partial fundoplication[137,138].

The decision to undergo anti-reflux surgery should be carefully considered, weighing the potential benefits of symptom relief and freedom from medication against the risks of surgery and the potential for symptom recurrence. This evaluation should take account of the variability in surgical outcomes, an individual’s overall health, and preferences[35].

Magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) (LINX reflux management system) is a procedure where an interlinked, flexible ring of magnetic beads coated with titanium is inserted laparoscopically around the LES to prevent reflux[139]. The ring allows the LES to open during swallows and keeps it closed at other times preventing reflux[139]. Manometric investigations have shown that this procedure restores loose LES pressures to normal pressures[140].

This procedure has rare complications, such as post-surgical dysphagia and erosion of the ring into the esophagus[141]. A follow-up study of post-MSA patients for 5 years showed good symptom improvement and long-term acid reduction[142]. Compared with fundoplication, patients undergoing MSA showed no significant difference in control of GERD symptoms but had shorter surgery times, shorter hospital stays, less bloating, and a better ability to belch[35,143].

The outcomes of anti-reflux surgery, including fundoplication, are often poorer in patients with obesity. This may be attributed to increased intra-abdominal pressure, which can lead to disruptions of the fundoplication and other surgical complications[144]. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), meanwhile, is a surgical option in patients with GERD with obesity to reduce gastric acid and prevent bile reflux[35]. Studies have shown that RYGB and fundoplication have comparable results[145]. RYGB should be considered for its combined effect of weight reduction and acid control. The patients being considered for it should be counselled about the risks and lifestyle modifications needed to make the surgery a success[35].

Despite the development of various endoscopic anti-reflux procedures such as Endocinch suturing, Stretta, Enteryx injection, and endoscopic full-thickness plication (GERD-X), their adoption remains limited due to factors like sparse clinical studies, modest effectiveness, high costs, and associated complications. As a result, these procedures are only available at a few specialized centers[110]. Of the endoscopic procedures, transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF), GERD-X, and Stretta have shown more promising results, and they are discussed below.

TIF, using the EsophyX device and T-fasteners, creates a flap valve covering 180° to 270° of the circumferences of the esophagogastric junction by plicating portions of the proximal stomach wall[146]. Meta-analyses showed a satisfactory reduction in symptoms and AET, and TIF is shown to be a safe and effective option for patients with GERD[147,148] ACG guidelines recommend TIF as well as fundoplication surgery for patients with refractory, proven GERD. TIF can be recommended if the patient is unwilling to undergo open surgery, has a small hiatus hernia of less than 2 cm, or has no severe erosive esophagitis[35].

This is a newer endoscopic plication device. Compared to EsophyX devices, it is a simpler and quicker surgical procedure with proven efficacy[149].

Stretta involves the application of thermal heat in the form of radiofrequency energy using a flexible transoral catheter and needle electrodes[150]. The mechanism of action of Stretta is not exactly clear, and the postulated mechanism includes the radiofrequency energy causing structural rearrangements of smooth muscles and interstitial cells of Cajal in the LES[150]. Stretta is considered a treatment option for patients with PPI-refractory GERD who are unwilling or not suitable for surgery[151]. However, according to the latest ACG guidelines, Stretta is not recommended as an alternative for medical or surgical treatment due to controversial data regarding its efficacy[35].

Neuromodulation therapies present newer avenues for the treatment of GERD. Examples of neuromodulation therapies for GERD, include transcutaneous electrical acustimulation (TEA), implantable LES electrical stimulation (LES-ES), electroacupuncture, and manual acupuncture. Systematic reviews have provided evidence supporting LES-ES and TEA as effective therapeutic options[85].

In TEA, bipolar electrical stimulation is delivered transcutaneously through two skin surface electrodes at acupuncture sites at the leg and wrist. A small study of 30 subjects showed an improvement in reflux-related symptoms and esopha

Electroacupuncture and manual acupuncture have somewhat similar methodologies involving electrical stimulation and manual stimulation at acupuncture sites in the body. The evidence related to these is poor[153,154]. The physiological basis of how these interventions work is unclear and could involve a placebo effect or even pain gaiting or modulation.

LES-ES meanwhile involves delivering bipolar electrical stimulation via two electrodes implanted in the LES submucosa approximately 1 cm apart. These leads are connected to a pulse generator implanted in the subcutaneous layer in the anterior abdominal wall. The electrical pulses were delivered at intervals in 12 sessions of 30-min durations per day. A study following 25 patients implanted with this device for over 2 years showed significant improvement in symptom scores and pH impedance metrics[155].

GERD left untreated can give rise to complications such as BE and esophageal cancer, though the estimated number is unclear[156].

If correctly identified as GERD through objective diagnostic tests and treated appropriately, the prognosis related to symptoms and complications with pharmacological treatment is positive[108]. However, most patients require long-term therapy as stopping medical treatment can bring about a symptom relapse[2].

Meanwhile, in a considerable number of patients, pharmacological treatment might prove fruitless due to many reasons. Such cases are called refractory GERD[157,158]. In these patients and those with complications, surgical options can offer a better prognosis[136].

Refractory GERD is defined as the failure of GERD symptoms to respond to 8 weeks of double doses of PPIs. This definition has some controversy as to whether it should be the standard once-daily dose or twice-daily PPI dose[159]. Common causes of refractory GERD include misdiagnosis, poor patient compliance, non-adherence to prescribed timing, hypersensitivity, rumination syndrome, supra-gastric belching, altered esophageal motility, and delayed gastric emptying[157,158]. The phenotype is also important, as systematic reviews showed that patients with NERD have less symptom relief than patients with erosive esophagitis on the same dose of PPI, are more likely to be treatment-resistant, and thus require further investigations[160]. Misdiagnosis is a cause of concern as symptoms of non-GERD disorders such as reflux like dyspepsia, gastroparesis, achalasia, and eosinophilic esophagitis overlap with GERD symptoms and reduce the odds of responding to PPIs.

As per ACG guidelines, the first step in the management of treatment refractive GERD is to improve treatment compliance and proper timing[157]. Doubling the dose of PPIs is also practiced, but studies have shown mixed results[161]. Typical GERD symptoms, obesity, and male sex were found to be positive predictors of increased relief when the PPI dose was increased[162]. One can switch to another PPI in the case of failure of treatment, but older PPIs, such as omeprazole, were found to have similar efficacy compared to the newer PPIs[163].

One of the main concerns regarding the treatment of refractory GERD is that it severely affects the quality of life of patients, leading to sleep disturbances, decreased work performance, and emotional stress[157].

Globally, GERD is a highly prevalent disorder, yet its true impact remains unclear due to a lack of comprehensive research and variations in diagnostic procedures and screening tools across different regions. GERD significantly diminishes quality of life, increases healthcare costs, and leads to several complications. It presents with a spectrum of symptoms other than the typical symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain and can progress to more severe conditions like BE and carcinoma. Early diagnosis and effective treatment strategies are essential to mitigate the burden of the disease on healthcare systems and improve patient outcomes. This underscores the need for standardized diagnostic criteria and more extensive epidemiological studies to determine the exact disease burden. Additionally, therapeutic trials are essential to evaluate emerging treatment options, ultimately enhancing healthcare outcomes for patients with GERD.

| 1. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2455] [Article Influence: 129.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-328; quiz 329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1136] [Cited by in RCA: 1120] [Article Influence: 93.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nirwan JS, Hasan SS, Babar ZU, Conway BR, Ghori MU. Global Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD): Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1057] [Cited by in RCA: 1265] [Article Influence: 115.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Belhocine K, Galmiche JP. Epidemiology of the complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2009;27:7-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Lee YY, McColl KE. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:339-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Herregods TV, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJ. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: new understanding in a new era. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1202-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miller LS, Vegesna AK, Brasseur JG, Braverman AS, Ruggieri MR. The esophagogastric junction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1232:323-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nandurkar S, Talley NJ. Epidemiology and natural history of reflux disease. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;14:743-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Levine DM, Ek WE, Zhang R, Liu X, Onstad L, Sather C, Lao-Sirieix P, Gammon MD, Corley DA, Shaheen NJ, Bird NC, Hardie LJ, Murray LJ, Reid BJ, Chow WH, Risch HA, Nyrén O, Ye W, Liu G, Romero Y, Bernstein L, Wu AH, Casson AG, Chanock SJ, Harrington P, Caldas I, Debiram-Beecham I, Caldas C, Hayward NK, Pharoah PD, Fitzgerald RC, Macgregor S, Whiteman DC, Vaughan TL. A genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett's esophagus. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1487-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Becker J, May A, Gerges C, Anders M, Veits L, Weise K, Czamara D, Lyros O, Manner H, Terheggen G, Venerito M, Noder T, Mayershofer R, Hofer JH, Karch HW, Ahlbrand CJ, Arras M, Hofer S, Mangold E, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Heinrichs SK, Hess T, Kiesslich R, Izbicki JR, Hölscher AH, Bollschweiler E, Malfertheiner P, Lang H, Moehler M, Lorenz D, Müller-Myhsok B, Ott K, Schmidt T, Whiteman DC, Vaughan TL, Nöthen MM, Hackelsberger A, Schumacher B, Pech O, Vashist Y, Vieth M, Weismüller J, Neuhaus H, Rösch T, Ell C, Gockel I, Schumacher J. Supportive evidence for FOXP1, BARX1, and FOXF1 as genetic risk loci for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1700-1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Argyrou A, Legaki E, Koutserimpas C, Gazouli M, Papaconstantinou I, Gkiokas G, Karamanolis G. Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease and analysis of genetic contributors. World J Clin Cases. 2018;6:176-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Wickramasinghe N, Thuraisingham A, Jayalath A, Wickramasinghe D, Samarasekara N, Yazaki E, Devanarayana NM. The association between symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease and perceived stress: A countrywide study of Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0294135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sontag SJ. Defining GERD. Yale J Biol Med. 1999;72:69-80. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Moraes-Filho JP, Chinzon D, Eisig JN, Hashimoto CL, Zaterka S. Prevalence of heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux disease in the urban Brazilian population. Arq Gastroenterol. 2005;42:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1256] [Cited by in RCA: 1262] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ayazi S, Hagen JA, Chan LS, DeMeester SR, Lin MW, Ayazi A, Leers JM, Oezcelik A, Banki F, Lipham JC, DeMeester TR, Crookes PF. Obesity and gastroesophageal reflux: quantifying the association between body mass index, esophageal acid exposure, and lower esophageal sphincter status in a large series of patients with reflux symptoms. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1440-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Goh KL. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: A historical perspective and present challenges. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 1:2-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sawada A, Sifrim D, Fujiwara Y. Esophageal Reflux Hypersensitivity: A Comprehensive Review. Gut Liver. 2023;17:831-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yamasaki T, O'Neil J, Fass R. Update on Functional Heartburn. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13:725-734. [PubMed] |

| 21. | De Giorgi F, Palmiero M, Esposito I, Mosca F, Cuomo R. Pathophysiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2006;26:241-246. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Shaheen N, Provenzale D. The epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326:264-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Behar J. Reflux esophagitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Arch Intern Med. 1976;136:560-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, Tytgat GN, Wallin L. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1518] [Cited by in RCA: 1653] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, Zerbib F, Mion F, Smout AJPM, Vaezi M, Sifrim D, Fox MR, Vela MF, Tutuian R, Tack J, Bredenoord AJ, Pandolfino J, Roman S. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut. 2018;67:1351-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 945] [Article Influence: 135.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Eluri S, Shaheen NJ. Barrett's esophagus: diagnosis and management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:889-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Triggs JR, Pandolfino JE. Esophageal Strictures. In: Kuipers EJ, editor. Encyclopedia of Gastroenterology. Amsterdam: Academic Press, 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Amarasiri LD, Pathmeswaran A, de Silva HJ, Ranasinha CD. Prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms and reflux-associated respiratory symptoms in asthma. BMC Pulm Med. 2010;10:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hirano I, Richter JE; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. ACG practice guidelines: esophageal reflux testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:668-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, Cabana M, DiLorenzo C, Gottrand F, Gupta S, Langendam M, Staiano A, Thapar N, Tipnis N, Tabbers M. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:516-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 610] [Cited by in RCA: 530] [Article Influence: 75.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Timmer R, Conchillo JM, Smout AJ. Addition of esophageal impedance monitoring to pH monitoring increases the yield of symptom association analysis in patients off PPI therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:453-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rossi P, Isoldi S, Mallardo S, Papoff P, Rossetti D, Dilillo A, Oliva S. Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring is helpful in managing children with suspected gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:910-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gyawali CP, Roman S, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Keller J, Pandolfino JE, Sifrim D, Tatum R, Yadlapati R, Savarino E; International GERD Consensus Working Group. Classification of esophageal motor findings in gastro-esophageal reflux disease: Conclusions from an international consensus group. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ambartsumyan L, Rodriguez L. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in children. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2014;10:16-26. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, Yadlapati R, Spechler SJ. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:27-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 156.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Iwakiri K, Kobayashi M, Kotoyori M, Yamada H, Sugiura T, Nakagawa Y. Relationship between postprandial esophageal acid exposure and meal volume and fat content. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:926-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Koul RK, Parveen S, Lahdol P, Rasheed PS, Shah NA. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) In Adult Kashmiri Population. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;10:62. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Song JH, Chung SJ, Lee JH, Kim YH, Chang DK, Son HJ, Kim JJ, Rhee JC, Rhee PL. Relationship between gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and dietary factors in Korea. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yamamichi N, Mochizuki S, Asada-Hirayama I, Mikami-Matsuda R, Shimamoto T, Konno-Shimizu M, Takahashi Y, Takeuchi C, Niimi K, Ono S, Kodashima S, Minatsuki C, Fujishiro M, Mitsushima T, Koike K. Lifestyle factors affecting gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a cross-sectional study of healthy 19864 adults using FSSG scores. BMC Med. 2012;10:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Lifestyle related risk factors in the aetiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1730-1735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yuan LZ, Yi P, Wang GS, Tan SY, Huang GM, Qi LZ, Jia Y, Wang F. Lifestyle intervention for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a national multicenter survey of lifestyle factor effects on gastroesophageal reflux disease in China. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819877788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Khan BA, Sodhi JS, Zargar SA, Javid G, Yattoo GN, Shah A, Gulzar GM, Khan MA. Effect of bed head elevation during sleep in symptomatic patients of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1078-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Hamilton JW, Boisen RJ, Yamamoto DT, Wagner JL, Reichelderfer M. Sleeping on a wedge diminishes exposure of the esophagus to refluxed acid. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:518-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:965-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Albarqouni L, Moynihan R, Clark J, Scott AM, Duggan A, Del Mar C. Head of bed elevation to relieve gastroesophageal reflux symptoms: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Shay SS, Conwell DL, Mehindru V, Hertz B. The effect of posture on gastroesophageal reflux event frequency and composition during fasting. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:54-60. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Khoury RM, Camacho-Lobato L, Katz PO, Mohiuddin MA, Castell DO. Influence of spontaneous sleep positions on nighttime recumbent reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2069-2073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kapur KC, Trudgill NJ, Riley SA. Mechanisms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in the lateral decubitus positions. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1998;10:517-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Allampati S, Lopez R, Thota PN, Ray M, Birgisson S, Gabbard SL. Use of a positional therapy device significantly improves nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Heidarzadeh-Esfahani N, Soleimani D, Hajiahmadi S, Moradi S, Heidarzadeh N, Nachvak SM. Dietary Intake in Relation to the Risk of Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2021;26:367-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kubo A, Block G, Quesenberry CP Jr, Buffler P, Corley DA. Dietary guideline adherence for gastroesophageal reflux disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Nebel OT, Fornes MF, Castell DO. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux: incidence and precipitating factors. Am J Dig Dis. 1976;21:953-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 590] [Cited by in RCA: 540] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Fan WJ, Hou YT, Sun XH, Li XQ, Wang ZF, Guo M, Zhu LM, Wang N, Yu K, Li JN, Ke MY, Fang XC. Effect of high-fat, standard, and functional food meals on esophageal and gastric pH in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and healthy subjects. J Dig Dis. 2018;19:664-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Hamoui N, Lord RV, Hagen JA, Theisen J, Demeester TR, Crookes PF. Response of the lower esophageal sphincter to gastric distention by carbonated beverages. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:870-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Wickramasinghe N, Thuraisingham A, Jayalath A, Wickramasinghe D, Samarasekera DN, Yazaki E, Devanarayana NM. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Sri Lanka: An island-wide epidemiological survey assessing the prevalence and associated factors. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024;4:e0003162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Chang CH, Wu CP, Wang JD, Lee SW, Chang CS, Yeh HZ, Ko CW, Lien HC. Alcohol and tea consumption are associated with asymptomatic erosive esophagitis in Taiwanese men. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Thomas FB, Steinbaugh JT, Fromkes JJ, Mekhjian HS, Caldwell JH. Inhibitory effect of coffee on lower esophageal sphincter pressure. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:1262-1266. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Price SF, Smithson KW, Castell DO. Food sensitivity in reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:240-243. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Chen SH, Wang JW, Li YM. Is alcohol consumption associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease? J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010;11:423-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Murphy DW, Castell DO. Chocolate and heartburn: evidence of increased esophageal acid exposure after chocolate ingestion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:633-636. [PubMed] |

| 61. | v Schönfeld J, Evans DF. [Fat, spices and gastro-oesophageal reflux]. Z Gastroenterol. 2007;45:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Holloway RH, Lyrenas E, Ireland A, Dent J. Effect of intraduodenal fat on lower oesophageal sphincter function and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 1997;40:449-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Ledeboer M, Masclee AA, Biemond I, Lamers CB. Effect of medium- and long-chain triglycerides on lower esophageal sphincter pressure: role of CCK. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G1160-G1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Lakananurak N, Pitisuttithum P, Susantitaphong P, Patcharatrakul T, Gonlachanvit S. The Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients. 2024;16:464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Penagini R, Mangano M, Bianchi PA. Effect of increasing the fat content but not the energy load of a meal on gastro-oesophageal reflux and lower oesophageal sphincter motor function. Gut. 1998;42:330-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Fernando I, Schmidt KA, Cromer G, Burhans MS, Kuzma JN, Hagman DK, Utzschneider KM, Holte S, Kraft J, Vaughan TL, Kratz M. The impact of low-fat and full-fat dairy foods on symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease: an exploratory analysis based on a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61:2815-2823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Gu C, Olszewski T, Vaezi MF, Niswender KD, Silver HJ. Objective ambulatory pH monitoring and subjective symptom assessment of gastroesophageal reflux disease show type of carbohydrate and type of fat matter. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221101289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Pointer SD, Rickstrew J, Slaughter JC, Vaezi MF, Silver HJ. Dietary carbohydrate intake, insulin resistance and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a pilot study in European- and African-American obese women. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:976-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Austin GL, Thiny MT, Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Shaheen NJ. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves gastroesophageal reflux and its symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1307-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Plaidum S, Patcharatrakul T, Promjampa W, Gonlachanvit S. The Effect of Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (FODMAP) Meals on Transient Lower Esophageal Relaxations (TLESR) in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Patients with Overlapping Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Nutrients. 2022;14:1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Cheng J, Ouwehand AC. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Probiotics: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2020;12:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Selling J, Swann P, Madsen LR 2nd, Oswald J. Improvement in Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms From a Food-grade Maltosyl-isomaltooligosaccharide Soluble Fiber Supplement: A Case Series. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018;17:40-42. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Corley DA, Kubo A. Body mass index and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2619-2628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:199-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 828] [Cited by in RCA: 798] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Hallan A, Bomme M, Hveem K, Møller-Hansen J, Ness-Jensen E. Risk factors on the development of new-onset gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. A population-based prospective cohort study: the HUNT study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:393-400; quiz 401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Chang P, Friedenberg F. Obesity and GERD. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:161-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Ness-Jensen E, Lindam A, Lagergren J, Hveem K. Weight loss and reduction in gastroesophageal reflux. A prospective population-based cohort study: the HUNT study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:376-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Singh M, Lee J, Gupta N, Gaddam S, Smith BK, Wani SB, Sullivan DK, Rastogi A, Bansal A, Donnelly JE, Sharma P. Weight loss can lead to resolution of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a prospective intervention trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Sanna L, Stuart AL, Berk M, Pasco JA, Girardi P, Williams LJ. Gastro oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)-related symptoms and its association with mood and anxiety disorders and psychological symptomology: a population-based study in women. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Naliboff BD, Mayer M, Fass R, Fitzgerald LZ, Chang L, Bolus R, Mayer EA. The effect of life stress on symptoms of heartburn. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:426-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Yamasaki T, Fass R. Reflux Hypersensitivity: A New Functional Esophageal Disorder. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Söderholm JD. Stress-related changes in oesophageal permeability: filling the gaps of GORD? Gut. 2007;56:1177-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Kamolz T. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Psychological Perspective of Interaction and Therapeutic Implications. In: Granderath FA, Kamolz T, Pointner R, editors. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Vienna: Springer, 2006. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 84. | Chandran S, Raman R, Kishor M, Nandeesh H. A randomized control trial of mindfulness-based intervention in relief of symptoms of anxiety and quality of life in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Indian Psychiatry. 2023;7:107. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 85. | Woo JY, Pikov V, Chen JDZ. Neuromodulation for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. J Transl Gastroenterol. 2023;1:47-56. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Weijenborg PW, de Schepper HS, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Effects of antidepressants in patients with functional esophageal disorders or gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:251-259.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Riehl ME, Keefer L. Hypnotherapy for Esophageal Disorders. Am J Clin Hypn. 2015;58:22-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Riehl ME, Pandolfino JE, Palsson OS, Keefer L. Feasibility and acceptability of esophageal-directed hypnotherapy for functional heartburn. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:490-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Kimura Y, Kamiya T, Senoo K, Tsuchida K, Hirano A, Kojima H, Yamashita H, Yamakawa Y, Nishigaki N, Ozeki T, Endo M, Nakanishi K, Sando M, Inagaki Y, Shikano M, Mizoshita T, Kubota E, Tanida S, Kataoka H, Katsumi K, Joh T. Persistent reflux symptoms cause anxiety, depression, and mental health and sleep disorders in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2016;59:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | McDonald-Haile J, Bradley LA, Bailey MA, Schan CA, Richter JE. Relaxation training reduces symptom reports and acid exposure in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:61-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Bitnar P, Hlava Š, Štovíček J, Kobesová A. Diaphragm in the role of esophageal sphincter and possibilities of treatment of esophageal reflux disease using physiotherapeutic procedures. Eur Respir J. 2018;52 (suppl 62):PA2446. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 92. | Zdrhova L, Bitnar P, Balihar K, Kolar P, Madle K, Martinek M, Pandolfino JE, Martinek J. Breathing Exercises in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia. 2023;38:609-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Qiu K, Wang J, Chen B, Wang H, Ma C. The effect of breathing exercises on patients with GERD: a meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:405-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Glasinovic E, Wynter E, Arguero J, Ooi J, Nakagawa K, Yazaki E, Hajek P, Psych CC, Woodland P, Sifrim D. Treatment of supragastric belching with cognitive behavioral therapy improves quality of life and reduces acid gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:539-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Shay SS, Johnson LF, Wong RK, Curtis DJ, Rosenthal R, Lamott JR, Owensby LC. Rumination, heartburn, and daytime gastroesophageal reflux. A case study with mechanisms defined and successfully treated with biofeedback therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:115-126. [PubMed] |

| 96. | Sun X, Shang W, Wang Z, Liu X, Fang X, Ke M. Short-term and long-term effect of diaphragm biofeedback training in gastroesophageal reflux disease: an open-label, pilot, randomized trial. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:829-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Gordon A, Gordon E, Berelowitz M, Bremner CH, Bremner CG. Biofeedback improvement of lower esophageal sphincter pressures and reflux symptoms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1983;5:235-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Choi JM, Yang JI, Kang SJ, Han YM, Lee J, Lee C, Chung SJ, Yoon DH, Park B, Kim YS. Association Between Anxiety and Depression and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Results From a Large Cross-sectional Study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:593-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Viazis N, Keyoglou A, Kanellopoulos AK, Karamanolis G, Vlachogiannakos J, Triantafyllou K, Ladas SD, Karamanolis DG. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of hypersensitive esophagus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1662-1667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Abdel-Aziz Y, Metz DC, Howden CW. Review article: potassium-competitive acid blockers for the treatment of acid-related disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:794-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Cossentino MJ, Mann K, Armbruster SP, Lake JM, Maydonovitch C, Wong RK. Randomised clinical trial: the effect of baclofen in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux--a randomised prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1036-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Xia HH, Wong WM, Lam SK, Wong BC. Head-to-head comparison of H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors in the treatment of erosive esophagitis: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4067-4077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 103. | Robinson M, Horn J. Clinical pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors: what the practising physician needs to know. Drugs. 2003;63:2739-2754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Liu Y, Zhu X, Li R, Zhang J, Zhang F. Proton pump inhibitor utilisation and potentially inappropriate prescribing analysis: insights from a single-centred retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e040473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Kirchheiner J, Glatt S, Fuhr U, Klotz U, Meineke I, Seufferlein T, Brockmöller J. Relative potency of proton-pump inhibitors-comparison of effects on intragastric pH. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Gralnek IM, Dulai GS, Fennerty MB, Spiegel BM. Esomeprazole versus other proton pump inhibitors in erosive esophagitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1452-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G, Smout AJ. Management of the patient with incomplete response to PPI therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:401-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Weijenborg PW, Cremonini F, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. PPI therapy is equally effective in well-defined non-erosive reflux disease and in reflux esophagitis: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:747-757, e350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019 Oct- . [PubMed] |

| 110. | Fuchs KH, Babic B, Breithaupt W, Dallemagne B, Fingerhut A, Furnee E, Granderath F, Horvath P, Kardos P, Pointner R, Savarino E, Van Herwaarden-Lindeboom M, Zaninotto G; European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). EAES recommendations for the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1753-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006;296:2947-2953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 845] [Cited by in RCA: 822] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310:2435-2442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Linsky A, Gupta K, Lawler EV, Fonda JR, Hermos JA. Proton pump inhibitors and risk for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:772-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Eom CS, Jeon CY, Lim JW, Cho EG, Park SM, Lee KS. Use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2011;183:310-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 115. | Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, Herbison P. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86:837-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, Sang Y, Chang AR, Coresh J, Grams ME. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and the Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:238-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 55.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Lo WK, Chan WW. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:483-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 118. | Reimer C, Søndergaard B, Hilsted L, Bytzer P. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:80-87, 87.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Cheung KS, Chan EW, Wong AYS, Chen L, Wong ICK, Leung WK. Long-term proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer development after treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a population-based study. Gut. 2018;67:28-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 120. | Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, Fihn SD, Jesse RL, Peterson ED, Rumsfeld JS. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009;301:937-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 739] [Cited by in RCA: 709] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, Broich K, Maier W, Fink A, Doblhammer G, Haenisch B. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitors With Risk of Dementia: A Pharmacoepidemiological Claims Data Analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:410-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Alhazzani W, Alenezi F, Jaeschke RZ, Moayyedi P, Cook DJ. Proton pump inhibitors versus histamine 2 receptor antagonists for stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:693-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 123. | Inadomi JM, Jamal R, Murata GH, Hoffman RM, Lavezo LA, Vigil JM, Swanson KM, Sonnenberg A. Step-down management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1095-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Furuta K, Adachi K, Komazawa Y, Mihara T, Miki M, Azumi T, Fujisawa T, Katsube T, Kinoshita Y. Tolerance to H2 receptor antagonist correlates well with the decline in efficacy against gastroesophageal reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1581-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |