Published online May 14, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i18.2467

Revised: February 28, 2024

Accepted: April 16, 2024

Published online: May 14, 2024

Processing time: 110 Days and 16.8 Hours

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) may affect the upper digestive tract; up to 20% of population in Western nations are affected by GERD. Antacids, his

To optimize diagnosis and treatment guidelines for GERD through a consensus based on Delphi method.

The availability of clinical studies describing the action of the multicompo

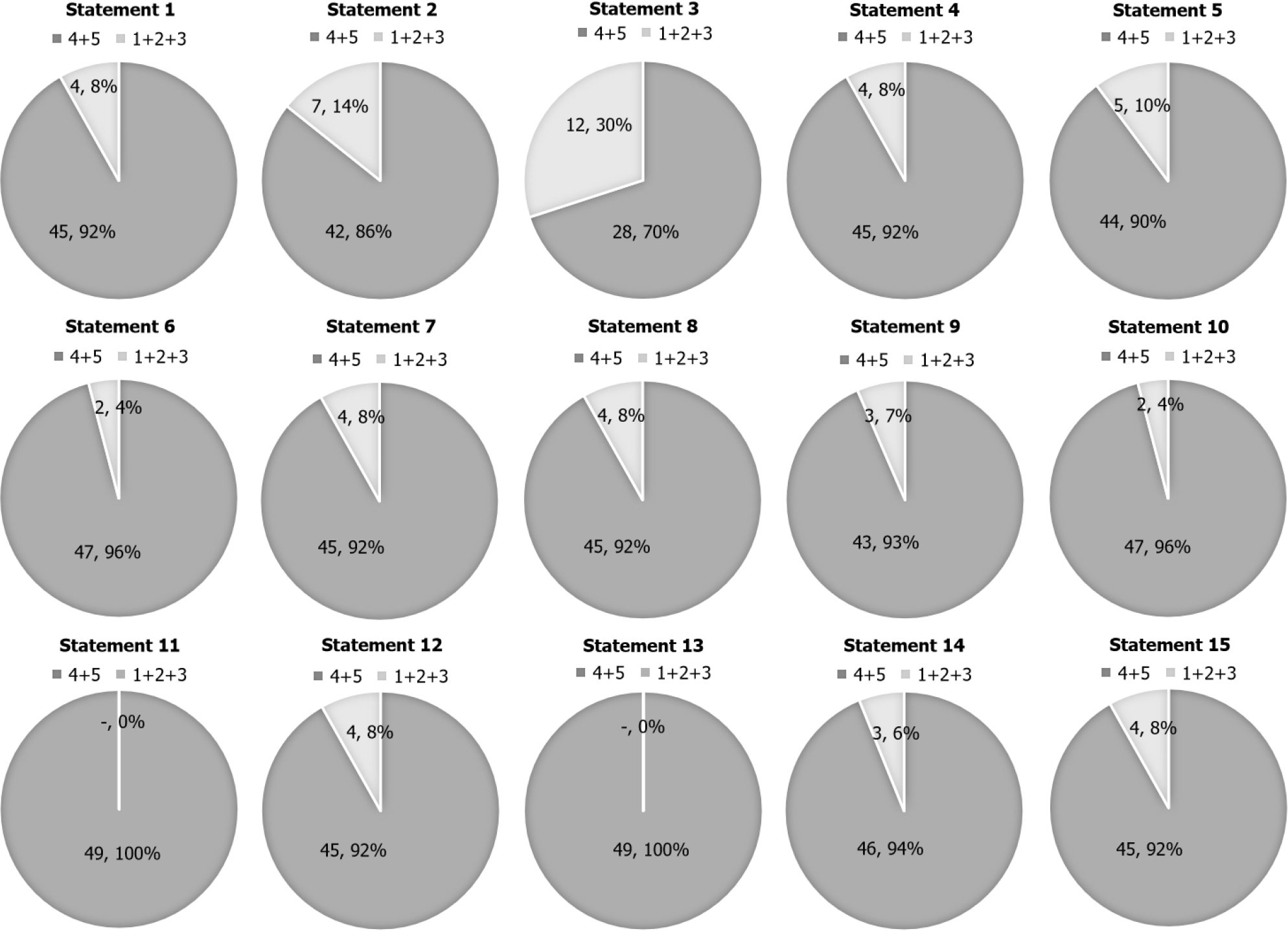

According to their routinary GERD practice and current clinical evidence, the panel members provided feedback to each questionnaire statement. The experts evaluated 15 statements and reached consensus on all 15. The statements regarding the GERD disease showed high levels of agreement, with consensus ranging from 70% to 92%. The statements regarding the GERD treatment also showed very high levels of agreement, with consensus ranging from 90% to 100%. This Delphi process was able to reach consensus among physicians in relevant aspects of GERD management, such as the adoption of a new approach to treat patients with GERD based on the overlapping between PPIs and Nux vomica-Heel. The consensus was unanimous among the physicians with different speciali

Nux vomica-Heel appears to be a valid opportunity for GERD treatment to favor the deprescription of PPIs and to maintain low disease activity together with the symptomatology remission.

Core Tip: This Delphi consensus suggests Nux vomica-Heel as a new therapeutic tool for the medical doctor who daily finds himself diagnosing and treating gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). Nux vomica-Heel is a multicomponent/mul

- Citation: Battaglia E, Bertolusso L, Del Prete M, Monzani M, Astegiano M. Overlapping approach Proton Pump Inhibitors/Nux vomica-Heel as new intervention for gastro-esophageal reflux management: Delphi consensus study. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(18): 2467-2478

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i18/2467.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i18.2467

The upper digestive tract can be affected by a chronic, common, and persistent disease known as gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD)[1,2]. Up to 20% of populations in Western nations are affected by GERD, and its incidence is rising globally[3]. When the distal esophagus is exposed to gastric content reflux, it might cause recurrent symptoms or mucosal injury[4]. Regurgitation, heartburn, and chest pain are the most significant examples of typical GERD symptoms[5]. GERD can also cause some extra-esophageal symptoms such as laryngitis, asthma, tooth erosion, and persistent cough[6].

A multimodal strategy is necessary for the treatment of GERD, taking into account the clinical presentation and, eventually, endoscopic findings[7]. Medical management comprises dietary and lifestyle changes as well as pharmaceutical therapy, primarily using drugs able to decrease stomach acid production. Recommendations for non-pharmacologic lifestyle changes include suggestions for modifying diet (content and timing), body positionings during meals and sleep, and weight control. Medication designed to reduce stomach acid are the backbone of pharmacologic treatment for GERD. Antacids, histamine H2-receptor antagonists (H2RA), and Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) represent the referring medications for GERD. Antacids should only be used as needed for symptom alleviation. Studies on alginic acid point out possible usefulness in symptom alleviation[8].

Based on a wealth of research showing consistently better heartburn and regurgitation control as well as improved healing with PPIs than with H2RAs, PPIs are the most frequently recommended drugs in GERD. At the time, when only two PPIs were marketed, a meta-analysis sheds light on PPI effectiveness: PPIs demonstrated a considerably faster healing rate (12%/wk) compared to H2RAs (6%/wk), as well as a quicker and more thorough relief from heartburn (11.5%/wk) compared to H2RAs (6.4%/wk)[9]. Long-term PPI treatment is advised for GERD complications such as severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles Classification grade C or D) and Barrett’s esophagus[10]. PPIs on demand administration, when PPIs are only taken when symptoms arise and stopped when they are relieved, can be taken under consideration. This method is suitable for patients who do not have Barrett’s esophagus or erosive esophagitis but still experience symptoms when PPI therapy is stopped[11].

Nevertheless, PPIs must be managed carefully, in fact: (1) Pathogens that would normally be killed by gastric acid can persist and cause enteric infections or be inhaled and cause pneumonia when gastric acid is suppressed[12]; and (2) reduced gastric acidity can impair the absorption of some vitamins (like B12) and minerals (like calcium)[13] and, concomitantly, increases gastrin blood level which is linked with an increased risk of carcinogenesis[12]. There are also evidences of the necessity of monitoring magnesium levels in patients receiving long-term PPI therapy[14].

Since socio-economic and epidemiological impact of GERD is worldwide very high.

Since PPIs have revolutionized the treatment of acid-related diseases, but they don’t fully meet all medical needs, such as the long-term treatment of these diseases, and a relevant number of subjects with GERD are non-responder to PPI-based acid-suppressive therapy.

Since the prolonged use of PPIs is often associated to adverse effects such as Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), malabsorption syndrome, osteoporosis, and cancer.

Since the symptomatology rebound is often linked to PPIs withdrawn.

Since in chronic treatment with PPIs the deprescription is advisable.

Because all above-mentioned premises, the need of alternative pharmacological tools for GERD management is nowadays a pharmaceutical challenge[15].

After the identification of potentially new medications to come up beside PPIs, it is essential to define new good clinical practices even through a consensus process.

The availability of clinical studies describing the action of the medication subject to the consensus - in this case Nux vomica-Heel (Tables 1 and 2) - is the basic prerequisite for the consensus itself[16-29].

| Characteristics of Nux vomica-Heel |

| Nux vomica-Heel tablets (also marketed as Gastricumeel®, Biologische Heilmittel Heel GmbH, Baden-Baden - Germany) is a natural, multicomponent low dose medication consisting of six ingredients from the homeopathic tradition useful for the treatment of bloating, acid reflux, and other symptoms as well as for heartburn |

| Each component of Nux vomica-Heel, according to literature (basic research), exerts a cohort of function |

| Nux vomica: Modulation of acid secretion[16-19] |

| Pulsatilla: Modulation of mucosal inflammation; modulation of mucosal secretions[21] |

| Antimonium crudum: Modulation of mucosal inflammation[22,23] |

| Argentum nitricum: Modulation of mucosal inflammation; increased EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor) release[24,25] |

| Arsenicum album: Modulation of mucosal inflammation; reduced VEGF (Vasal Endothelial Growth Factor) release[26,27] |

| Carbo vegetabilis: Chelation of toxins[28,29] |

| According to the composition, three can be the main actions of Nux vomica-Heel: |

| (1) Aetiologic, through a direct modulation of acid secretion |

| (2) Symptomatic, through the modulation of gastric mucosa acute inflammation |

| (3) Preventive, through the modulation of gastric mucosa inflammation progression |

| Keywords | Components of Nux vomica-Heel | |||||

| Nux vomica | Argentum nitricum | Arsenicum album | Pulsatilla | Antimonium crudum | Carbo vegetabilis | |

| Mucosal inflammation | X | X | X | |||

| Gastric pyrosis | X | X | X | X | ||

| Abdominal distension | X | X | X | |||

| Abdominal pain | X | |||||

| Abdominal colic | X | |||||

| Chelating action on toxins | X | |||||

| Alcoholic gastritis | X | X | ||||

| Epigastric pain | X | |||||

| Gastrodynia | X | |||||

To achieve the best clinical outcomes and minimize possible adverse effects linked to PPIs use, a possibility is offered by an overlapping therapeutic strategy, consisting of the protocol below.

In patients with chronic PPI treatment for GERD symptoms (which is the object of this Delphi consensus), the administration of Nux vomica-Heel and PPI in overlapping for PPI decalage is as follows:

First two weeks: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosage schedule plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h) according to the medication’s datasheet.

Third week: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosing schedule on alternate days plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h).

Fourth week: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosing scheme two days a week plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h).

From the fifth week: Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h). PPI as needed.

An alternative overlapping strategy in patients with GERD symptoms, after clinical remission obtained with PPI, for the maintenance of Low Disease Activity (LDA) and the remission of symptomatology, is the long-term use of Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h).

To address these considerations, a Delphi consensus process was undertaken to develop clinically relevant statements that will lay the opportunity to use Nux vomica-Heel as overlapping therapy with PPIs.

A modified Delphi process was used to achieve a consensus among a group of Italian GERD specialists. The Delphi process uses anonymous and interactive feedback and voting to achieve consensus among a panel of independent experts (Consensus Panel) by means of stepwise refinement of responses.

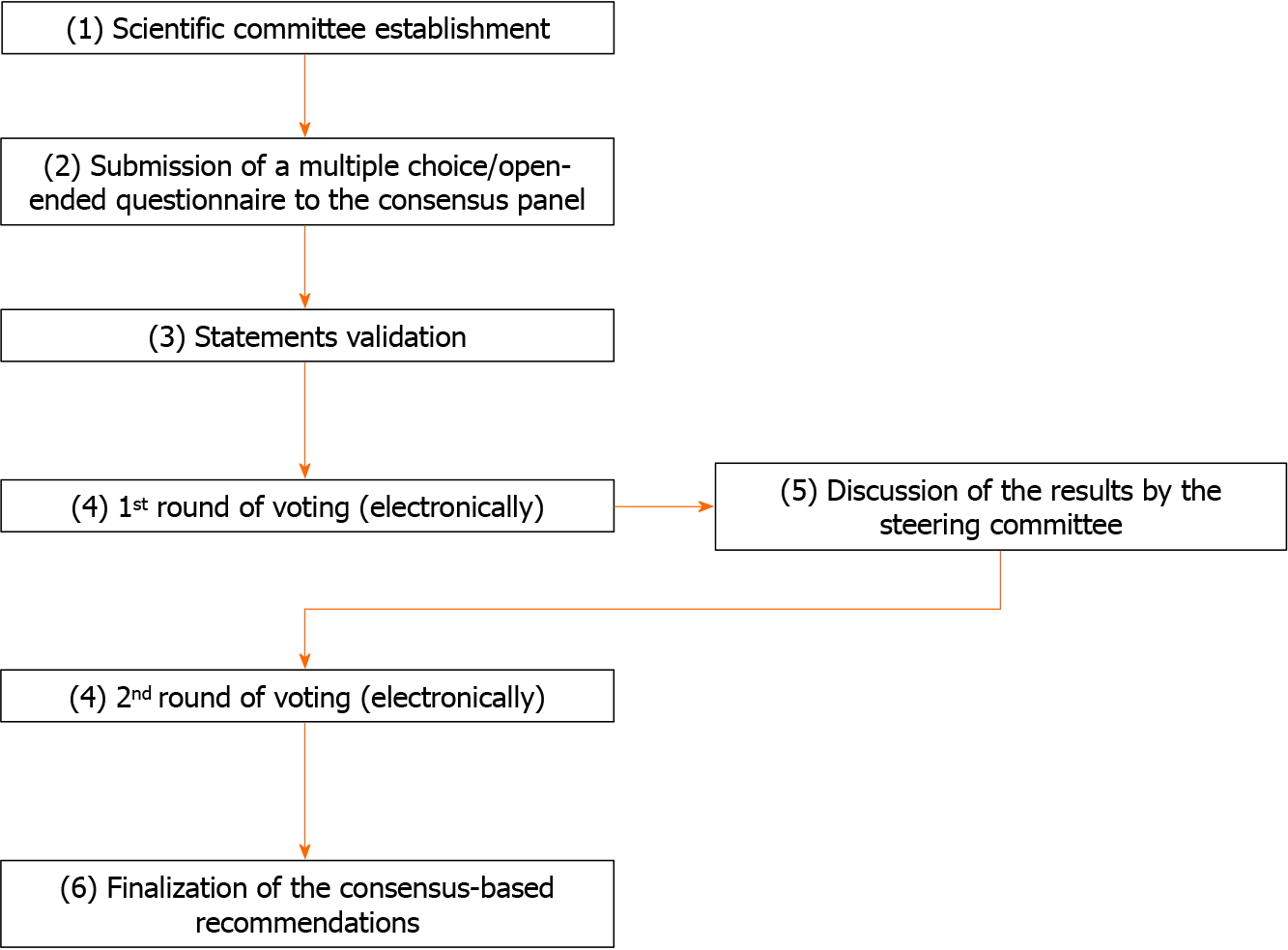

The Delphi consensus process was conducted between March 2023 and May 2023 among Italian physicians involved in GERD care, consisting of the following steps: (1) Establishment of a scientific committee of 5 Italian clinicians, gastroenterologists and general practitioners (GPs), all experts in GERD, to define consensus topics; (2) submission of a multiple choice/open-ended questionnaire to the Consensus Panel; (3) statements validation; (4) submission of the identified statements to the Consensus Panel in two rounds; (5) discussion of the results by the steering committee; and (6) finalization of the consensus-based recommendations (Figure 1).

In a first step a web-based multiple-choice questionnaire was submitted to the Consensus Panel to solicit specific information about the content area of the Delphi process.

The Voting Consensus Panel consisted of 49 Italian physicians with an interest in gastroenterology covering a broad geographical area, with participants from the different Italian Regions and with different specializations: Gastroenterology (19%), otolaryngology (16%), geriatrics (10%), and general medicine (55%).

The scientific committee analyzed the literature, determined areas that required investigation (in agreement with the multiple-choice questionnaire results), and identified two topics of interest: (1) GERD disease; and (2) GERD treatment. Statements for each of these topics were then formulated and validated.

The Delphi process involved two rounds of questioning of panel experts using an online platform. In round 1, Delphi Consensus Panel was asked to rate their level of agreement with each questionnaire statement on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The expert panel individually and anonymously provided feedback to each questionnaire statement based on routine GERD practice and current clinical evidence. The number and percentage of participants who scored each item as 1-2 (disagreement) or as 4-5 (agreement) was calculated.

The first-round results were then discussed by the scientific committee in a virtual meeting. For each questionnaire statement, consensus was considered to have been achieved based on the agreement of at least 66.6% of the expert panel and the acceptance of the scientific committee. In round 2, the updated questionnaire, which included statements that did not reach consensus in the first round, was redistributed for the re-evaluation of these statements. All statements reaching consensus in round 1 were removed. Panelists were asked to rate again statements that had not reached consensus using the same voting method described for round 1.

A total of 49 experts in GERD care evaluated 15 statements (Table 3) and reached consensus on all 15 (Table 4 and Figure 2).

| Topic A: GERD disease |

| (1) The epidemiological and socio-economic impact of GERD is very high |

| (2) GERD is diagnosed in the presence of typical symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation and/or retrosternal pain) |

| (3) The presence of only atypical symptoms (chest pain, cough, asthma, hoarseness, frequent throat clearing) without the co-presence of typical symptoms, would not be suggestive for GERD diagnosis |

| (4) Based on the symptoms, GERD can be diagnosed, and the treatment be prescribed by GPs, Otolaryngologists, and Geriatricians other than Gastroenterologists |

| Topic B: GERD treatment |

| (5) The most common management strategy for GERD targets heartburn reduction and inducing repair of the inflamed mucosa |

| (6) In case of GERD, PPIs are the most prescribed drugs for GERD symptoms resolution |

| (7) The most common adverse effects associated with PPIs are SIBO, gastrointestinal infections, malabsorption, osteoporosis, and neoplasia |

| (8) The main issue in the clinical management of patients affected by GERD is the symptoms rebound when the PPI therapy is discontinued |

| (9) PPIs deprescription is advisable when alternative therapies are available |

| (10) The natural low dose multicomponent medication Nux vomica-Heel is effective in the management of patients affected by acid-related disorders |

| (11) The prescription of Nux vomica-Heel in patients affected by acid-related disorders is desirable also in light of its high safety and tolerability profile |

| (12) In patients under long-term treatment with PPI, to clinically manage GERD symptoms, the administration of Nux vomica-Heel in overlapping with the PPI is recommended to reduce and suspend the use of the PPI |

| (13) In patients presenting GERD symptoms, the use of Nux vomica-Heel can be recommended as maintenance therapy after discontinuing the PPI |

| (14) In patients who presented GERD symptoms, after remission obtained with PPIs, LDA and symptoms remission can be maintained by a long-term administration of Nux vomica-Heel, 1 tablet sublingually 3 times per day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h) |

| (15) In patients under long-term treatment with PPI, the overlapping directions for Nux vomica-Heel and PPI (for the PPI discontinuation) are the following: |

| First two weeks: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosage schedule plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h) |

| Third week: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosing schedule on alternate days plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h) |

| Fourth week: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosing scheme two days a week plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h) |

| From the fifth week: Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h). PPI as needed |

| (1) Strongly disagree | (2) Disagree | (3) Undecided | (4) Agree | (5) Strongly agree | Sum votes 4-5 | 1st round consensus (reached if % greater than 66%) | 2nd round consensus (reached if % greater than 66%) | |

| Topic A: GERD disease | ||||||||

| Statement 1 1st round | 0/49 | 1/49 | 3/49 | 28/49 | 17/49 | 45 | 92 | |

| Statement 2 1st round | 1/49 | 3/49 | 3/49 | 35/49 | 7/49 | 42 | 86 | |

| Statement 3 1st round | 1/49 | 16/49 | 6/49 | 23/49 | 3/49 | 26 | 53 | |

| Statement 3 2nd round | 3/40 | 9/40 | 0/40 | 26/40 | 2/40 | 28 | 70 | |

| Statement 4 1st round | 1/49 | 2/49 | 1/49 | 25/49 | 20/49 | 45 | 92 | |

| Topic B: GERD treatment | ||||||||

| Statement 5 1st round | 0/49 | 2/49 | 3/49 | 36/49 | 8/49 | 44 | 90 | |

| Statement 6 1st round | 0/49 | 1/49 | 1/49 | 39/49 | 8/49 | 47 | 96 | |

| Statement 7 1st round | 0/49 | 2/49 | 2/49 | 30/49 | 15/49 | 45 | 92 | |

| Statement 8 1st round | 0/49 | 1/49 | 3/49 | 32/49 | 13/49 | 45 | 92 | |

| Statement 9 1st round | 1/49 | 1/49 | 1/49 | 30/49 | 16/49 | 46 | 94 | |

| Statement 10 1st round | 0/49 | 0/49 | 2/49 | 36/49 | 11/49 | 47 | 96 | |

| Statement 11 1st round | 0/49 | 0/49 | 0/49 | 30/49 | 19/49 | 49 | 100 | |

| Statement 12 1st round | 0/49 | 1/49 | 3/49 | 33/49 | 12/49 | 45 | 92 | |

| Statement 13 1st round | 0/49 | 0/49 | 0/49 | 33/49 | 16/49 | 49 | 100 | |

| Statement 14 1st round | 0/49 | 1/49 | 2/49 | 32/49 | 14/49 | 46 | 94 | |

| Statement 15 1st round | 0/49 | 2/49 | 2/49 | 35/49 | 10/49 | 45 | 92 | |

The statements regarding the GERD disease showed high levels of agreement, with consensus ranging from 70% to 92% (Table 4).

Statement 1: The epidemiological and socio-economic impact of GERD is very high (92% agreement).

GERD is common worldwide. The stability of our global age-standardized prevalence estimates over time suggests that the epidemiology of the disease has not changed, but the estimates of all-age prevalence and the years lived with disability, which increased between 1990 and 2017, suggest that the burden of GERD is nonetheless increasing because of aging and population growth[30].

Statement 2: GERD is diagnosed in the presence of typical symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation and/or pain in the chest) (86% agreement).

GERD is one of the most frequent gastrointestinal diseases[1]. It is defined when both esophageal and extra-esophageal symptoms, and/or lesions resulting from the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus are present. GERD symptoms can be typical, such as heartburn and regurgitation, and atypical, such as chest pain, chronic cough, laryngeal burn, globus, and hoarseness[31].

Statement 3: The presence of only atypical symptoms (chest pain, cough, asthma, hoarseness, frequent throat clearing) without the co-presence of typical symptoms, would not be suggestive for GERD diagnosis (70% agreement).

Of interest, despite this consensus, not all members of the expert panel agreed with the Statement 3. This may be due to the different specializations of the panel. Throat symptoms are a common reason for referral from primary to secondary care—the sensation of a lump in the throat affects up to half of the general population — at some stage PPIs are widely used in both primary and secondary care as empirical treatment for throat symptoms. Published meta-analyses of PPIs for the treatment of throat symptoms include small scale studies of limited value. This trial found no evidence of benefit for patients with persistent throat symptoms who were treated empirically with a PPI, demonstrating that the co-presence of typical symptoms is decisive for the diagnosis of GERD[32].

Statement 4: Based on the symptoms, GERD can be diagnosed, and the treatment be prescribed by GPs, Otolaryngologists, and Geriatricians other than Gastroenterologists (92% agreement).

The exact nature of reflux disease causing hoarseness continues to be a controversial and vexing diagnosis for otolaryngologists, gastroenterologists, and other practitioners who may be approached by those seeking relief for hoarseness and other voice symptoms[33].

The statements regarding the GERD treatment showed very high levels of agreement, with consensus ranging from 90% to 100% (Table 4).

Statement 5: The most common management strategy for GERD targets heartburn reduction and inducing repair of the inflamed mucosa (90% agreement).

Statement 6: In case of GERD, PPIs are the most prescribed drugs for GERD symptoms resolution (96% agreement).

In patients who continue to have bothersome GERD-related symptoms despite lifestyle modifications, medical therapy is commonly offered or used. Medical therapy includes antacids, sodium alginate, H2RAs, PPIs, Carafate, Transient Lower Esophageal Sphincter Relaxation (TLESR) reducer, and prokinetics. PPIs are considered the most effective medical therapy for GERD, due to their profound and consistent acid suppression[34].

GERD therapy is challenging and suppression of acid secretion or prokinetics do not cure all cases. Some drugs with protective action on the esophageal mucosa have been used alternatively or in association with PPIs and/or prokinetics[35].

Statement 7: The most common adverse effects associated with PPI’s are SIBO, gastrointestinal infections, malabsorption, osteoporosis, and neoplasia (92% agreement).

PPIs represent a milestone in the management of gastric acid-related disorders since their introduction to the market in 1989. However, widespread PPIs use has led to emerging evidence of long-term adverse effects not previously described, creating an increasing concern for their possible side effects such as susceptibility to respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, impaired absorption of nutrients, increased risk of kidney, liver, and cardiovascular diseases, dementia, until rarely enteroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract[36].

Statement 8: The main issue in the clinical management of patients affected by GERD is the symptoms rebound when the PPI therapy is discontinued (92% agreement).

Statement 9: PPIs deprescription is advisable when alternative therapies are available (93% agreement).

Daily PPI exposure for more than 4 wk is likely to trigger a rebound of acid hypersecretion about 15 d after discontinuation, and lasting from a few days to several weeks depending on the duration of the exposure[37].

Abrupt PPI discontinuation may result in short-term rebound acid hypersecretion that can mimic symptom return[38].

Evidence supports a patient-centered approach to PPI deprescription involving stepping down the dose before ceasing or switching to pro-re-nata- (PRN; ‘as needed’) use. Abrupt PPI discontinuation may result in short-term rebound acid hypersecretion that can mimic symptom return. This can be minimized with gradual dose tapering prior to discontinuation and managed with PRN treatment. Prescribers should discuss the rationale for PPI deprescribing and involve patients in developing the deprescribing plan[38].

Because we know that duration and dose of PPI administration increase the likelihood of adverse events, avoiding unnecessary use of this class of drugs should be our first goal. PPIs should be given in the lowest dose that controls the patient’s symptoms. However, in patients who failed once-daily PPI, adding antacids, sodium alginate, sucralfate, H2RAs, TLESR reducers, or prokinetics should be considered, but only after compliance and lifestyle modifications have been implemented[39].

Patients should receive the lowest dose of PPI that control their symptoms; the need for chronic PPI treatment should be evaluated on a regular basis and alternative options to chronic PPI treatment should be sought out in patients with high risk for PPI-related adverse events[34].

Statement 10: The natural low dose multicomponent medication Nux vomica-Heel is effective in the management of patients affected by acid-related disorders (96% agreement).

Statement 11: The prescription of Nux vomica-Heel in patients affected by acid-related disorders is desirable also in light of its high safety and tolerability profile (100% agreement).

A comparative study addressed the use of Nux vomica-Heel in the treatment of suspected gastritis and heartburn in general. The results indicate that Nux vomica-Heel, either as monotherapy or in combination with nonpharmacological treatments such as diets, is noninferior to PPIs. Treatment compliance and tolerability were reported to be better on Nux vomica-Heel. The results suggest that it is worth considering Nux vomica-Heel as a safe and effective treatment option in the management of dyspepsia and heartburn (GERD)[40].

Statement 12: In patients under long-term treatment with PPI, to clinically manage GERD symptoms, the administration of Nux vomica-Heel in overlapping with the PPI is recommended to reduce and suspend the use of the PPI (92% agreement).

Statement 13: In patients presenting GERD symptoms, the use of Nux vomica-Heel can be recommended as maintenance therapy after discontinuing the PPI (100% agreement).

Apart from being a possible alternative to PPIs, Nux vomica-Heel has a potential role to play in supporting patients who find it difficult to withdraw from PPIs[40].

Statement 14: In patients who presented GERD symptoms, after remission obtained with PPIs, LDA and symptoms remission can be maintained by a long-term administration of Nux vomica-Heel, 1 tablet sublingually 3 times per day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h) (94% agreement).

Daily administration of PPIs for more than 4 wk can trigger a rebound acid hypersecretion after their sudden discontinuation which may last from a few days to several weeks, depending on the duration of the administration[37,38].

In patients with GERD symptoms, after clinical remission obtained with PPI, the maintenance of LDA and the remission of symptomatology are possible with long-term use of Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h).

Statement 15: In patients under long-term treatment with PPI, the overlapping directions for Nux vomica-Heel and PPI (for the PPI discontinuation) are the following:

First two weeks: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosage schedule plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h).

Third week: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosing schedule on alternate days plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h).

Fourth week: PPI at the recommended dose according to the dosing scheme two days a week plus Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h).

From the fifth week: Nux vomica-Heel 1 tablet sublingually 3 times a day far from meals (as needed 1 tablet every 15 min for no more than 2 h). PPI as needed (92% agreement).

In addition to being a possible alternative to PPIs (statement 14), Nux vomica-Heel plays a potential role in deprescribing PPIs[40].

Evidence supports that an effective approach to deprescribe PPIs, based on a progressive decalage according to a precise dose reduction timetable before stopping or switching PPIs administration to as-needed use, should be considered[38].

To achieve the progressive decalage of PPIs, the option offered by Nux vomica-Heel administered according to the above deprescription timetable may be considered.

For many years, GERD has been mainly considered as an acid-related disease and, therefore, predominantly treated with PPIs. Unfortunately, about 20%-40% of patients are no-responder to PPI therapy, suggesting that, perhaps, acid hypersecretion does not represent the only etiopathogenetic factor[41].

Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate a different therapeutic strategy aimed to consider the etiopathogenesis of GERD from a systemic point of view, as a dysregulation of one or more networks, in agreement with Systems Medicine interpretation[42].

This possible new therapeutic approach must be grounded on acting upon more than one pathophysiological mechanism, and with multiple outcomes (etiological, symptomatic, preventive) through multicomponent/multitarget medications, especially when recommended in overlapping with PPIs.

Alongside drugs and medical devices able to protect the esophageal mucosa, other pharmacologic interventions can be considered preferably in overlapping with PPIs given the good efficacy of the latter.

The main outcome of the Delphi consensus model discussed in this article was to identify an intervention model that would allow the deprescription of PPIs in chronic patients in order to limit possible adverse effects of these molecules (maintaining at the same time a LDA, a good symptom control, and high clinical safety, compliance, and tolerability).

For this purpose, the medication Nux vomica-Heel was taken into consideration. Nux vomica-Heel was previously evaluated in a prospective controlled observational study which demonstrated its non-inferiority, compared to PPIs, in the treatment of dyspepsia, heartburn, and related symptoms[40].

This Delphi process was able to reach consensus among physicians in relevant aspects of GERD management, particularly focusing on the adoption of a new approach to treat patients with GERD.

Consensus was reached on all statements related to GERD diagnosis and on all statements related to GERD treatment. The consensus was unanimous among the physicians with different specializations underlying the uniqueness of the agreement reached to identify in the overlapping approach between PPIs and Nux vomica-Heel a new intervention model for GERD management.

In conclusion, according to the consensus, Nux vomica-Heel appears to be a valid opportunity for the treatment of GERD to favor the deprescription of PPIs in patients with chronic PPIs treatment and the maintenance of LDA together with the remission of symptomatology. The results of this consensus encourage to perform larger clinical studies on this topic.

The authors sincerely thank all the members of the expert panel that participated in the Delphi consensus: Sergio Albanese - Negrar VR; Margherita Assirati - San Giuliano Milanese MI; Luca Franco Mario Barili - Bellusco MB; Sergio Antonio Barone - Parabita LE; Giovanna Borrone - Firenze; Donatella Brazioli - Torino; Franco Bruni - Verona; Vito Carrozzo - Melendugno LE; Miriam Checcacci - Roma; Giovanni Ciardiello - Barano d'Ischia NA; Simonetta Colasanti - Roma; Carla Cortelloni - Montecreto MO; Carlo De Angelis - San Ferdinando di Puglia BAT; Aurelio de Vicariis - Sangano TO; Valentina Degani - Merlara PD; Francesco Deriva - Afragola NA; Marianna Di Maso - Torremaggiore FG; Marcellino Di Muccio - San Potito Sannitico CE; Bruno Ugo Fiorentino - Valmadrera LC; Maria Floro - Termoli CB; Nicola Gabriele - Larino CB; Pietro Gagliardi - Marano di Napoli NA; Fabio Garibaldi - Lucca; Francesco Gerbino - Gallipoli LE; Valerio Giangrande - Roma; Girolamo Giorlando - Grugliasco TO; Sara Griseri - Alassio SV; Elena Guidi - Rovereto TN; Pietro Lobue - Palermo; Bibiana Lucifora - Catania; Alessandra Magnano - Torino; Assunta Maio - Milano; Guido Marini - Grosseto; Antonio Mastrostefano - Roma; Samanta Mazzocchi - Castel San Giovanni PC; Francesco Messineo - Messina; Rita Monterubbianesi - Roma; Herbert Rainer - Tradate VA; Maurizio Romano - Nocera Inferiore SA; Rosaria Russo - Catania; Gaetano Samperi - Mascalucia CT; Giovanni Scornavacca - Catania; Anna Scorpiniti - Montello BG; Raffaella Scoyni - Roma; Simone Spagliardi - Sedriano MI; Maria Maddalena Squillante - Manfredonia FG; Claudia Stagnoli - Castelnuovo VR; Michele Trevisani - Pianoro BO; Franco Tripodi - Salerno; Maria Vegni - Abbadia San Salvatore SI; Desiree Zahlane - Riccione RN; Laura Zocchi - Roma.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade A, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Lv L, China; Wang D, China S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Fass R, Boeckxstaens GE, El-Serag H, Rosen R, Sifrim D, Vaezi MF. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Davis TA, Gyawali CP. Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Diagnosis and Management. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2024;30:17-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ustaoglu A, Nguyen A, Spechler S, Sifrim D, Souza R, Woodland P. Mucosal pathogenesis in gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32:e14022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2006;367:2086-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Bazzoli F, Ford AC. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2018;67:430-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saber H, Ghanei M. Extra-esophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease: controversies between epidemiology and clicnic. Open Respir Med J. 2012;6:121-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, Yadlapati R, Spechler SJ. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:27-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 155.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Wilkinson J, Wade A, Thomas SJ, Jenner B, Hodgkinson V, Coyle C. Randomized clinical trial: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of alginate-antacid (Gaviscon Double Action) chewable tablets in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khan M, Santana J, Donnellan C, Preston C, Moayyedi P. Medical treatments in the short term management of reflux oesophagitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD003244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Savarino V, Marabotto E, Zentilin P, Furnari M, Bodini G, De Maria C, Tolone S, De Bortoli N, Frazzoni M, Savarino E. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and pharmacological treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13:437-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boghossian TA, Rashid FJ, Thompson W, Welch V, Moayyedi P, Rojas-Fernandez C, Pottie K, Farrell B. Deprescribing versus continuation of chronic proton pump inhibitor use in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD011969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Laine L, Ahnen D, McClain C, Solcia E, Walsh JH. Review article: potential gastrointestinal effects of long-term acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:651-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Losurdo G, Caccavo NLB, Indellicati G, Celiberto F, Ierardi E, Barone M, Di Leo A. Effect of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use on Blood Vitamins and Minerals: A Primary Care Setting Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Souza CC, Rigueto LG, Santiago HC, Seguro AC, Girardi AC, Luchi WM. Multiple electrolyte disorders triggered by proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: Case reports with a mini-review of the literature. Clin Nephrol Case Stud. 2024;12:6-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Heisig J, Bücker B, Schmidt A, Heye AL, Rieckert A, Löscher S, Hirsch O, Donner-Banzhoff N, Wilm S, Barzel A, Becker A, Viniol A. Efficacy of a computer based discontinuation strategy to reduce PPI prescriptions: a multicenter cluster-randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2023;13:21633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yin W, Wang TS, Yin FZ, Cai BC. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of brucine and brucine N-oxide extracted from seeds of Strychnos nux-vomica. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;88:205-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen J, Wang X, Qu YG, Chen ZP, Cai H, Liu X, Xu F, Lu TL, Cai BC. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity and pharmacokinetics of alkaloids from seeds of Strychnos nux-vomica after transdermal administration: effect of changes in alkaloid composition. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:181-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wettergren A, Wøjdemann M, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits gastropancreatic function by inhibiting central parasympathetic outflow. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G984-G992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Varaprasad V, Kumar RB, Podha S. The stimulatory effect of strychnine alkaloid on production of glucagon like peptide-1 hormone (glp-1) in the gut of alloxan induced diabetic rabbits. Int J Pharm Biol Sci. 2018;8:74-81. |

| 20. | Duan H, Zhang Y, Xu J, Qiao J, Suo Z, Hu G, Mu X. Effect of anemonin on NO, ET-1 and ICAM-1 production in rat intestinal microvascular endothelial cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104:362-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hu Y, Chen X, Duan H, Hu Y, Mu X. Pulsatilla decoction and its active ingredients inhibit secretion of NO, ET-1, TNF-alpha, and IL-1 alpha in LPS-induced rat intestinal microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mahesh S, Kozymenko T, Kolomiiets N, Vithoulkas G. Antimonium crudum in pediatric skin conditions: A classical homeopathic case series. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:818-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cincura C, Costa RS, De Lima CMF, Oliveira-Filho J, Rocha PN, Carvalho EM, Lessa MM. Assessment of Immune and Clinical Response in Patients with Mucosal Leishmaniasis Treated with Pentavalent Antimony and Pentoxifylline. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nadworny PL, Wang J, Tredget EE, Burrell RE. Anti-inflammatory activity of nanocrystalline silver-derived solutions in porcine contact dermatitis. J Inflamm (Lond). 2010;7:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Suganya TR, Devasena T. Exploring the mechanism of anti-inflammatory activity of phyto-stabilized silver nanorods. Dig J Nanomater Bios. 2015;10:277-282. |

| 26. | Alex AA, Ganesan S, Palani HK, Balasundaram N, David S, Lakshmi KM, Kulkarni UP, Nisham PN, Korula A, Devasia AJ, Janet NB, Abraham A, Srivastava A, George B, Padua RA, Chomienne C, Balasubramanian P, Mathews V. Arsenic Trioxide Enhances the NK Cell Cytotoxicity Against Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia While Simultaneously Inhibiting Its Bio-Genesis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang J, Li C, Zheng Y, Lin Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Z. Inhibition of angiogenesis by arsenic trioxide via TSP-1-TGF-β1-CTGF-VEGF functional module in rheumatoid arthritis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:73529-73546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zellner T, Prasa D, Färber E, Hoffmann-Walbeck P, Genser D, Eyer F. The Use of Activated Charcoal to Treat Intoxications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:311-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | de Gunzburg J, Ghozlane A, Ducher A, Le Chatelier E, Duval X, Ruppé E, Armand-Lefevre L, Sablier-Gallis F, Burdet C, Alavoine L, Chachaty E, Augustin V, Varastet M, Levenez F, Kennedy S, Pons N, Mentré F, Andremont A. Protection of the Human Gut Microbiome From Antibiotics. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:628-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | GBD 2017 Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:561-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rettura F, Bronzini F, Campigotto M, Lambiase C, Pancetti A, Berti G, Marchi S, de Bortoli N, Zerbib F, Savarino E, Bellini M. Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Management Update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:765061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | O'Hara J, Stocken DD, Watson GC, Fouweather T, McGlashan J, MacKenzie K, Carding P, Karagama Y, Wood R, Wilson JA. Use of proton pump inhibitors to treat persistent throat symptoms: multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;372:m4903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Korsunsky SRA, Camejo L, Nguyen D, Mhaskar R, Chharath K, Gaziano J, Richter J, Velanovich V. Resource utilization and variation among practitioners for evaluating voice hoarseness secondary to suspected reflux disease: A retrospective chart review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e31056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sandhu DS, Fass R. Current Trends in the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gut Liver. 2018;12:7-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Surdea-Blaga T, Băncilă I, Dobru D, Drug V, Frățilă O, Goldiș A, Grad SM, Mureșan C, Nedelcu L, Porr PJ, Sporea I, Dumitrascu DL. Mucosal Protective Compounds in the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. A Position Paper Based on Evidence of the Romanian Society of Neurogastroenterology. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2016;25:537-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yibirin M, De Oliveira D, Valera R, Plitt AE, Lutgen S. Adverse Effects Associated with Proton Pump Inhibitor Use. Cureus. 2021;13:e12759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Rochoy M, Dubois S, Glantenet R, Gautier S, Lambert M. Gastric acid rebound after a proton pump inhibitor: Narrative review of literature. Therapie. 2018;73:237-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Turner JP, Thompson W, Reeve E, Bell JS. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors. Aust J Gen Pract. 2022;51:845-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fass R. Alternative therapeutic approaches to chronic proton pump inhibitor treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:338-45; quiz e39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | van Haselen R, Cesnulevicius K. Treatment of Dyspepsia, Heartburn, and Related Symptoms with Gastricumeel Compared to Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Prospective Reference-Controlled Observational Study. Complement Med Res. 2021;28:234-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | El-Serag H, Becher A, Jones R. Systematic review: persistent reflux symptoms on proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care and community studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:720-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (39)] |

| 42. | Barabási AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:56-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3846] [Cited by in RCA: 3032] [Article Influence: 216.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |