Published online Mar 14, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i10.1638

Peer-review started: November 19, 2022

First decision: December 10, 2022

Revised: January 15, 2023

Accepted: February 22, 2023

Article in press: February 22, 2023

Published online: March 14, 2023

Processing time: 110 Days and 21.4 Hours

Endofaster is an innovative technology that can be combined with upper gastro

To assess the diagnostic performance of this technology and its impact on the management of H. pylori in the real-life clinical setting.

Patients undergoing routine UGE were prospectively recruited. Biopsies were taken to assess gastric histology according to the updated Sydney system and for rapid urease test (RUT). Gastric juice sampling and analysis was performed using the Endofaster, and the diagnosis of H. pylori was based on real-time ammonium measurements. Histological detection of H. pylori served as the diagnostic gold standard for comparing Endofaster-based H. pylori diagnosis with RUT-based H. pylori detection.

A total of 198 patients were prospectively enrolled in an H. pylori diagnostic study by Endofaster-based gastric juice analysis (EGJA) during the UGE. Biopsies for RUT and histological assessment were performed on 161 patients (82 men and 79 women, mean age 54.8 ± 19.2 years). H. pylori infection was detected by histology in 47 (29.2%) patients. Overall, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value (NPV) for H. pylori diagnosis by EGJA were 91.5%, 93.0%, 92.6%, 84.3%, and 96.4%, respectively. In patients on treatment with proton pump inhibitors, diagnostic sensitivity was reduced by 27.3%, while specificity and NPV were unaffected. EGJA and RUT were comparable in diagnostic performance and highly concordant in H. pylori detection (κ-value = 0.85).

Endofaster allows for rapid and highly accurate detection of H. pylori during gastroscopy. This may guide taking additional biopsies for antibiotic susceptibility testing during the same procedure and then selecting an individually tailored eradication regimen.

Core Tip: Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection can be rapidly achieved within the framework of gastroscopy by rapid urease test (RUT) or by gastric juice analysis with Endofaster. In this prospective observational study, we compared the accuracy of these two methods. Gastric juice analysis with Endofaster could reliably detect H. pylori with high accuracy, showing a diagnostic performance comparable to that of RUT and a major advantage of an immediate result. Intraprocedural H. pylori detection (or exclusion) is crucial to optimize the diagnostic approach and improve the management of infection. The diagnosis of Endofaster may guide additional sampling for antibiotic susceptibility testing in positive patients or avoid unnecessary biopsies in negative patients.

- Citation: Vasapolli R, Ailloud F, Suerbaum S, Neumann J, Koch N, Macke L, Schirra J, Mayerle J, Malfertheiner P, Schulz C. Intraprocedural gastric juice analysis as compared to rapid urease test for real-time detection of Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(10): 1638-1647

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i10/1638.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i10.1638

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infects nearly half of the world's population, with variable prevalence rates ranging from 20%-30% in Western countries to > 70% in Africa[1]. H. pylori infection causes chronic active gastritis and may lead to severe complications including gastroduodenal ulcers, gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma[2]. The diagnosis of active H. pylori infection is achieved by non-invasive tests such as the urea breath test (UBT) and stool antigen tests (SAT), as well as invasive methods based on endoscopy and gastric biopsies for histological assessment, rapid urease test (RUT), culture and molecular tests.

Current guidelines recommend testing for H. pylori in all patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE)[3]. The Endofaster has been introduced as new diagnostic device, which consents the detection of H. pylori by performing biochemical analysis of gastric juice aspirated during gastroscopy. Previous validation studies have shown that this device has high accuracy for H. pylori detection and reported diagnostic values similar to those of UBT and histology[4,5]. The diagnostic performance of the Endofaster has not been compared with that of the RUT, which shares a similar characteristic in terms of providing results in a short-term temporal context through endoscopic examination. This allows for therapeutic management immediately after the diagnostic procedure.

The aim of this prospective study was to validate the diagnostic performance of the Endofaster for H. pylori detection in patients who underwent UGE compared to conventional RUT.

Consecutive patients undergoing routine UGE to investigate dyspepsia or other alarming symptoms (weight loss, anemia, vomiting, abdominal pain, or dysphagia) were prospectively recruited at the Ludwig Maximilians University Hospital in Munich from January to June 2022.

Subjects were recruited within the ERANET Bavaria and Helicopredict projects (German clinical trials register, DRKS-ID: DRKS00028629), large-scale prospective studies focused on studying different aspects of H. pylori infection, including improving the diagnosis and management of H. pylori, determining local antibiotic resistance spectrum, with the aim of developing a genotypic resistance testing database for predicting antibiotic susceptibility and evaluating the impact of the microbiome of the upper gastrointestinal tract on gastric carcinogenesis.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and government authorities and was conducted in accordance with current Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki[6]. All recruited subjects provided written informed consent for participation. Previous gastric surgery and intake of anticoagulants or any antibiotic therapy within 4 wk prior to endoscopy were exclusion criteria. Regular use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) or previous H. pylori eradication therapy did not represent exclusion criteria, but were recorded in detail. Only patients not taking a PPI or H. pylori treatment-naïve patients were considered to meet the desired minimum sample size.

Enrolled patients underwent a diagnostic UGE using standard video gastroscopes (GIF-HQ190, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). All examinations were performed with sedation using Propofol and/or Midazolam. An analysis of gastric juice was performed at the beginning of the UGE by Endofaster. Special attention was paid during intubation: The stomach was handled first and no fluid was allowed to be sucked during passage through the oral cavity or esophagus. In order to avoid possible dilution of gastric juice prior to collection the administration of endoscopic premedications (i.e. dimethicone, N-acetylcysteine, pronase etc.) before endoscopy were not allowed. Furthermore, washing with water and cleaning the endoscopic lens were avoided until sampling was completed. After endoscopic assessment of the mucosa, gastric biopsies were obtained. Two biopsies - one from antrum and one from corpus (both from the greater curvature) - were taken for the RUT (Pronto Dry® New, Medical Instruments Corporation, Herford, Germany). RUT was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and assessed for positive response during gastroscopy and 1 h after biopsy sampling. The inspection time taken to perform the diagnostic UGE (excluding the time spent on gastric juice aspiration and on biopsy sampling) and the time it took until first detection of H. pylori positivity by RUT were recorded. Further biopsies (2 from antrum, 1 from angulus and 2 from corpus) were subjected to routine histology according to the updated Sydney system[7] and current guidelines[3]. In each biopsy sampling set the following stainings were performed: Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff and a H. pylori specific staining (modified Giemsa staining).

Real-time gastric juice analysis was performed using an Endofaster 21-42 (NISO Biomed, Turin, Italy), which is interposed between the endoscope and the suction system (Figure 1). This innovative device analyzes the first 3.3 mL of gastric juice aspirated at the beginning of the UGE. The Endofaster provides information regarding gastric pH based on hydrogen ion concentration and H. pylori detection based on the measurement of ammonium derived from bacterial urease activity within 60-90 s[4,5]. Considering that approximately 10-20 s (max 30 s) are needed to aspirate the gastric juice through the scope a final H. pylori diagnosis is provided within the first 2 min from the beginning of the endoscopic procedure. Except for the time spent on the initial gastric juice collection no additional time is required for Endofaster use during the endoscopic procedure. In line with previous studies, we used a cut-off value of > 62 ppm/mL to indicate the presence of H. pylori[8].

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0.0 (IBM Corporation, New York, NY, United States). Numerical variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for both Endofaster and RUT using histology as the gold standard. The concordance between Endofaster and RUT results was assessed by using Cohen’s κ-value. The McNemar test was used to compare sensitivities and specificities between the two tests.

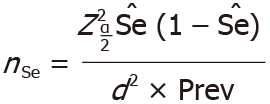

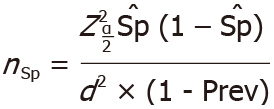

Sample size estimation was based on a 95%CI and the calculation methods of Buderer et al[9] were applied using following formula:

Where Z is the normal distribution value set to 1.96, corresponding to the 95%CI, and d is the maximum acceptable width of the 95%CI, set at 10%. Based on a previous study, Endofaster had a sensitivity (Se) of 97.1% and a specificity (Sp) of 89.7% for H. pylori detection[5]. Recently, the prevalence of H. pylori infection (Prev) in Germany was estimated to be 35.3% (95%CI: 31.2-39.4)[1]. As a result, using the criteria listed above, this study required a minimum of 31 H. pylori-positive patients (nSe) and 55 H. pylori-negative patients (nSp), resulting in a minimum total sample size of 86 subjects. Patients with PPI use or prior H. pylori eradication therapy were not considered to achieve the minimum sample size required. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

A total of 198 patients undergoing elective UGE were enrolled. Of these, 182 underwent gastric juice analysis with the Endofaster. After excluding patients who reported antibiotic intake within the last 4 wk (n = 10, 5.2%), patients who could not undergo biopsy due to anticoagulation therapy (n = 8, 4.1%) and patients with insufficient volume of aspirated gastric juice for Endofaster analysis (n = 13, 6.7%) a total of 161 patients (male: 82, female: 79, mean age 54.8 ± 19.2 years) were included in the analysis. 67 (41.6%) patients were on ongoing PPI therapy and 94 patients (58.4%) did not report any PPI therapy. The demographic, endoscopic, and histopathological characteristics of the study cohort are shown in Table 1. A flow chart of the study's recruitment is shown in Figure 2.

| Characteristics | Value |

| Overall | 161 |

| Male | 82 (50.9) |

| Female | 79 (49.1) |

| Age, mean ± SD (range) yr | 54.8 ± 19.2 (19-90) |

| H. pylori positive | 47 (29.2) |

| H. pylori negative | 114 (70.8) |

| Patients without PPI therapy | 94 (58.4) |

| Male | 46 (48.9) |

| Female | 48 (51.1) |

| Age, mean ± SD (range) yr | 50.3 ± 19.2 (19-86) |

| H. pylori positive | 37 (39.4) |

| H. pylori negative | 57 (60.6) |

| Patients with PPI therapy | 67 (41.6) |

| Male | 36 (53.7) |

| Female | 31 (46.3) |

| Age, mean ± SD (range) yr | 58.9 ± 19.2 (23-90) |

| H. pylori positive | 10 (14.9) |

| H. pylori negative | 57 (85.1) |

| Endoscopic and histopathological findings1 | |

| Normal | 13 (8.1) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 26 (16.1) |

| Chronic gastritis | 84 (52.2) |

| Erosive gastritis | 32 (19.9) |

| Gastric ulcer | 5 (3.1) |

| Duodenal ulcer | 3 (1.9) |

| Gastritis with low-grade PL | 36 (22.4) |

| Gastritis with high-grade PL | 4 (2.5) |

| Others2 | 6 (3.7) |

The average duration of the diagnostic UGE was 8.5 min. H. pylori infection was diagnosed in 47 (29.2%) patients on histopathology. Endofaster results were positive in 51 patients (31.6%), while RUT was positive in 45 (28.0%) cases. A positive RUT reaction was detected during endoscopy in 37 subjects (78.7%), with a mean positive reaction time of 16.4 min. The overall diagnostic performances of Endofaster and RUT for H. pylori detection as compared to histology (gold standard) are shown in Table 2. Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV and NPV were 91.5%, 93.0%, 92.6%, 84.3% and 96.4% for Endofaster, and 93.6%, 99.1%, 97.5%, 97.8% and 97.4% for RUT, respectively. No significant differences were observed in the diagnostic performances of the Endofaster and the RUT (P > 0.05). This was confirmed by an almost perfect agreement of H. pylori detection between the two tests (κ-value = 0.85).

| Endofaster | Rapid urease test | |||||

| Overall | No PPI | Ongoing PPI therapy | Overall | No PPI | Ongoing PPI therapy | |

| Sensitivity | 91.5 (79.6-97.6) | 97.3 (85.8-99.9) | 70.0 (34.8-93.3) | 93.6 (82.5-98.7) | 97.3 (85.8-99.9) | 80.0 (44.4-97.5) |

| Specificity | 93.0 (84.6-96.9) | 96.5 (87.9-99.6) | 89.5 (78.5-96.0) | 99.1 (95.2-100) | 100 (93.7-100) | 98.3 (90.6-100) |

| PPV | 84.3 (73.3-91.3) | 94.7 (82.2-98.6) | 53.9 (33.1-73.4) | 97.8 (86.2-99.7) | 100 (-) | 88.9 (52.8-98.3) |

| NPV | 96.4 (91.2-98.6) | 98.2 (88.8-99.7) | 94.4 (86.8-97.8) | 97.4 (92.7-99.1) | 98.3 (89.2-99.8) | 96.6 (89.0-99.0) |

| Accuracy | 92.6 (87.3-96.1) | 96.8 (91.0-99.3) | 86.6 (76.0-93.7) | 97.5 (93.8-99.3) | 98.9 (94.2-100) | 95.5 (87.5-99.1) |

Both Endofaster and RUT showed excellent diagnostic performances when considering only patients without ongoing PPI therapy (n = 94). In this subgroup, 37 (39.4%) subjects were histopathologically diagnosed as positive for H. pylori.

Among patients treated with PPI (n = 67), the presence of H. pylori was detected by histology in 10 subjects (14.9%). In this subgroup, a reduction in sensitivity, PPV and accuracy was observed for both Endofaster and RUT, whereas specificity and NPV remained almost unchanged (Table 2). Again, in the subgroup analysis, there were no significant differences in diagnostic performances between Endofaster and RUT (P > 0.05).

Several diagnostic methods are performed on biopsies obtained during the UGE to detect H. pylori with high accuracy. They are highly accurate, but have the limitation to delay even a few days in providing diagnostic results, thus not allowing an immediate therapeutic decision. RUT is the only exception in clinical practice that allows relatively rapid detection of H. pylori, usually within 1 h after UGE[10-12].

Here, we report on the diagnostic performance of Endofaster-based gastric juice analysis (EGJA), an innovative technology that allows intraprocedural H. pylori detection compared to RUT. We found that the high accuracy (> 90%) of EGJA was comparable to that of RUT for H. pylori detection, confirming previous reports of the high accuracy of EGJA compared to histology[4,5,8,13]. A previous prospective study of EGJA in 182 patients determined the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of H. pylori to be 97.1%, 89.7% and 92.6%, respectively, compared to histology being used as the gold standard as well as UBT, which was used for reclassification of H. pylori status in case of discordance between EGJA and histology results[5]. A multicenter study of 525 consecutive patients reported an overall sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of 87%, 84% and 85%, respectively, when compared to histology[8].

We have observed impaired diagnostic sensitivity in patients with PPI in EGJA and RUT, which is a common phenomenon for all tests, including non-invasive tests[3,14]. In the context of PPI intake, only histology remains highly sensitive when gastric biopsies are taken from the proximal stomach[15,16]. This is related to the PPI-induced shift from antrum-predominant to corpus-predominant gastritis. We found that 3 out of 4 false negatives and 6 out of 8 false positives (75%) in EGJA were registered in patients on PPI therapy. Two of the three false negatives (66%) diagnosed by the RUT were PPI users. EGJA and RUT rely on the same principles related to ammonium concentration and H. pylori urease activity. Therefore, both tests are influenced by the reduction of bacterial load by PPI, which may lead to false negative results. Furthermore, an elevated pH in the stomach environment may lead to an overgrowth of other non-H. pylori bacteria with urease activity[17]. Several different urease-positive bacterial strains, such as Staphylococcus capitis subsp. urealyticus and Streptococcus salivarium, have been isolated in gastric juice and mucosal samples from patients with gastric hypochloridria[18]. The higher abundance of these strains may interfere with urea metabolism and explain the increased number of false-positive cases among patients on PPI therapy. It is necessary to analyze the gastric microbiota and functionality profiles of PPI patients in order to further address this interesting topic. In our study, the low prevalence of H. pylori-infected subjects (only 14.9%) within the group of patients on PPI therapy is a limitation because of an underpowered statistical analysis. Using histology as the gold standard for H. pylori-diagnosis in a cohort with relatively low-prevalence of H. pylori may represent a further limitation of this study. Histopathological diagnosis of H. pylori may suffer from potential sampling error due to the patchy distribution of the bacterium[19]. However, by using the updated Sydney system based on biopsies from 5 different sites and applying different staining methods for H. pylori detection the accuracy of H. pylori-diagnosis by histology is not inferior to any non-invasive test (13C-UBT/SAT). In support for the validity of histology as gold standard for H. pylori detection, we found also no indirect signs of H. pylori-gastritis (i.e. neutrophils infiltration in the gastric mucosa) in the absence of H. pylori.

EGJA has the advantage of obtaining more rapid diagnostic results when performing endoscopy compared to RUT. During endoscopy (within a time period of approximately 10 min), a positive signal in the RUT for the presence of H. pylori was recorded in 78.7% of those producing H. pylori positivity at the end of the reading time in our study, consistent with the time interval of response reported in previous validation studies[12,20], whereas EGJA resulted in the diagnosis of H. pylori within 2 min after starting with UGE. The intraprocedural detection of H. pylori infection combined with measurement of gastric pH can guide the endoscopist on the most appropriate approach to complete the diagnostic assessment, i.e., whether or not to carry out additional biopsies for gastritis severity staging and antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST). This has become an absolute requirement for the selection of the eradication regimen due to the high antibiotic resistance rates of clarithromycin, metronidazole and fluoroquinolones[21]. Real-time detection of H. pylori suggests carrying out additional biopsies for AST during UGE and selecting an H. pylori eradication regimen accordingly.

Such a strategy would have a substantial impact on cost-effectiveness by reducing the duration of the procedure and lowering costs due to histological or microbiological analysis of negative gastric biopsies, an aspect that has been previously addressed by others[8].

Future studies will explore the possibility of combining EGJA with in situ molecular genetic antibiotic resistance testing. Promising data in this field were revealed by a recent meta-analysis of four studies that evaluated gastric juice-based genotypic detection of H. pylori antibiotic resistance to clarithromycin compared to standard culture-based methods[22].

In conclusion, Endofaster’s gastric juice analysis is a highly accurate method for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, comparable to RUT. EGJA-based H. pylori diagnosis has an advantage in terms of on-site immediacy of diagnosis. In patients on PPI therapy, sensitivity is reduced, but NPV and specificity are not affected. Real-time detection of H. pylori along with the determination of gastric pH during endoscopy adds important information on the need for additional biopsies for more detailed histological assessment and antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection can be rapidly achieved within the framework of gastroscopy by rapid urease test (RUT) or by gastric juice analysis with Endofaster.

The diagnostic performance of the Endofaster has not been compared with that of the RUT, which shares a similar characteristic in terms of providing results in a short-term temporal context through endoscopic examination.

The objective of this prospective study was to validate the diagnostic performance of the Endofaster for H. pylori detection in patients who underwent gastroscopy compared to the diagnostic accuracy of a standard RUT.

Patients undergoing routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy were prospectively recruited. Biopsies were taken to assess gastric histology according to the updated Sydney system and for RUT. Gastric juice sampling and analysis was performed using the Endofaster, and the diagnosis of H. pylori was based on real-time ammonium measurements. Histological detection of H. pylori served as the diagnostic gold standard for comparing Endofaster-based H. pylori diagnosis with RUT-based H. pylori detection.

Gastric juice analysis with Endofaster could reliably detect H. pylori with an overall sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of 91.5%, 93.0%, 92.6%, 84.3%, and 96.4%, respectively. Gastric juice analysis with Endofaster and RUT were comparable in diagnostic performance and highly concordant in H. pylori detection (κ-value = 0.85).

Endofaster’s gastric juice analysis is a highly accurate method for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, comparable to RUT. EGJA-based H. pylori diagnosis has an advantage in terms of on-site immediacy of diagnosis.

Intraprocedural diagnosis of H. pylori-infection by Endofaster may guide additional sampling for antibiotic susceptibility testing in positive patients or avoid unnecessary biopsies in negative patients.

The authors would like to thank Ulrich Lang for organizing the data, Paul Muller, Tanja Nowak, Federico Urzi and the staff of NISO Biomed for technical assistance and for providing the Endofaster device free of charge during the recruitment period. Medical writing assistance was provided by Dr. Philip Benz.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie, Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group; United European Gastroenterology.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Germany

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Noh CK, South Korea; Rocha R, Brazil S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1361] [Cited by in RCA: 2047] [Article Influence: 255.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P; faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1322] [Cited by in RCA: 1180] [Article Influence: 118.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, Gasbarrini A, Hunt RH, Leja M, O'Morain C, Rugge M, Suerbaum S, Tilg H, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2022;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 660] [Article Influence: 220.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tucci A, Tucci P, Bisceglia M, Marchegiani A, Papadopoli G, Fusaroli P, Spada A, Pistoletto MO, Cristino M, Poli L, Villani A, Bucci M, Marinelli M, Caletti G. Real-time detection of Helicobacter Pylori infection and atrophic gastritis: comparison between conventional methods and a novel device for gastric juice analysis during endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:966-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Costamagna G, Zullo A, Bizzotto A, Spada C, Hassan C, Riccioni ME, Marmo C, Strangio G, Di Rienzo TA, Cammarota G, Gasbarrini A, Repici A. Real-time diagnosis of H. pylori infection during endoscopy: Accuracy of an innovative tool (EndoFaster). United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:339-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191-2194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16597] [Cited by in RCA: 18255] [Article Influence: 1521.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3221] [Cited by in RCA: 3550] [Article Influence: 122.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Zullo A, Germanà B, Galliani E, Iori A, de Pretis G, Manfredi G, Buscarini E, Buonocore MR, Monica F. Optimizing the searching for H. pylori in clinical practice with EndoFaster(Ⓡ). Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:772-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Buderer NM. Statistical methodology: I. Incorporating the prevalence of disease into the sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:895-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 537] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pohl D, Keller PM, Bordier V, Wagner K. Review of current diagnostic methods and advances in Helicobacter pylori diagnostics in the era of next generation sequencing. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4629-4660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 11. | McNicholl AG, Ducons J, Barrio J, Bujanda L, Forné-Bardera M, Aparcero R, Ponce J, Rivera R, Dedeu-Cuso JM, Garcia-Iglesias P, Montoro M, Bejerano A, Ber-Nieto Y, Madrigal B, Zapata E, Loras-Alastruey C, Castro M, Nevarez A, Mendez I, Bory-Ros F, Miquel-Planas M, Vera I, Nyssen OP, Gisbert JP; Helicobacter pylori Study Group of the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG). Accuracy of the Ultra-Rapid Urease Test for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:651-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Said RM, Cheah PL, Chin SC, Goh KL. Evaluation of a new biopsy urease test: Pronto Dry, for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sánchez Rodríguez E, Sánchez Aldehuelo R, Ríos León R, Martín Mateos RM, García García de Paredes A, Martín de Argila C, Caminoa A, Albillos A, Vázquez-Sequeiros E. Clinical validation of Endofaster® for a rapid diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2020;112:23-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gatta L, Vakil N, Ricci C, Osborn JF, Tampieri A, Perna F, Miglioli M, Vaira D. Effect of proton pump inhibitors and antacid therapy on 13C urea breath tests and stool test for Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:823-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lan HC, Chen TS, Li AF, Chang FY, Lin HC. Additional corpus biopsy enhances the detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in a background of gastritis with atrophy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Logan RP, Walker MM, Misiewicz JJ, Gummett PA, Karim QN, Baron JH. Changes in the intragastric distribution of Helicobacter pylori during treatment with omeprazole. Gut. 1995;36:12-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sanduleanu S, Jonkers D, De Bruine A, Hameeteman W, Stockbrügger RW. Non-Helicobacter pylori bacterial flora during acid-suppressive therapy: differential findings in gastric juice and gastric mucosa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:379-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Brandi G, Biavati B, Calabrese C, Granata M, Nannetti A, Mattarelli P, Di Febo G, Saccoccio G, Biasco G. Urease-positive bacteria other than Helicobacter pylori in human gastric juice and mucosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1756-1761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Genta RM, Graham DY. Comparison of biopsy sites for the histopathologic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: a topographic study of H. pylori density and distribution. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:342-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Perna F, Ricci C, Gatta L, Bernabucci V, Cavina M, Miglioli M, Vaira D. Diagnostic accuracy of a new rapid urease test (Pronto Dry), before and after treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2005;51:247-254. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Megraud F, Bruyndonckx R, Coenen S, Wittkop L, Huang TD, Hoebeke M, Bénéjat L, Lehours P, Goossens H, Glupczynski Y; European Helicobacter pylori Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Working Group. Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe in 2018 and its relationship to antibiotic consumption in the community. Gut. 2021;70:1815-1822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Si XB, Bi DY, Lan Y, Zhang S, Huo LY. Gastric Juice-Based Genotypic Methods for Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Antibiotic Resistance Testing: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2021;32:53-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rugge M, Meggio A, Pennelli G, Piscioli F, Giacomelli L, De Pretis G, Graham DY. Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut. 2007;56:631-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Capelle LG, de Vries AC, Haringsma J, Ter Borg F, de Vries RA, Bruno MJ, van Dekken H, Meijer J, van Grieken NC, Kuipers EJ. The staging of gastritis with the OLGA system by using intestinal metaplasia as an accurate alternative for atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1150-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |