Published online Nov 7, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i41.5944

Peer-review started: July 9, 2022

First decision: September 2, 2022

Revised: September 15, 2022

Accepted: October 19, 2022

Article in press: October 19, 2022

Published online: November 7, 2022

Processing time: 117 Days and 11 Hours

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement is an effective intervention for recurrent tense ascites. Some studies show an increased risk of acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) associated with TIPS placement. It is not clear whether ACLF in this context is a consequence of TIPS or of the pre-existing liver disease.

To better understand the risks of TIPS in this challenging setting and to compare them with those of conservative therapy.

Two hundred and fourteen patients undergoing their first TIPS placement for recurrent tense ascites at our tertiary-care center between 2007 and 2017 were identified (TIPS group). Three hundred and ninety-eight patients of the same time interval with liver cirrhosis and recurrent tense ascites not undergoing TIPS placement (No TIPS group) were analyzed as a control group. TIPS indication, diagnosis of recurrent ascites, further diagnoses and clinical findings were obtained from a database search and patient records. The in-hospital mortality and ACLF incidence of both groups were compared using 1:1 propensity score matching and multivariate logistic regressions.

After propensity score matching, the TIPS and No TIPS groups were comparable in terms of laboratory values and ACLF incidence at hospital admission. There was no detectable difference in mortality (TIPS: 11/214, No TIPS 13/214). During the hospital stay, ACLF occurred more frequently in the TIPS group than in the No TIPS group (TIPS: 70/214, No TIPS: 57/214, P = 0.04). This effect was confined to patients with severely impaired liver function at hospital admission as indicated by a significant interaction term of Child score and TIPS placement in multivariate logistic regression. The TIPS group had a lower ACLF incidence at Child scores < 8 points and a higher ACLF incidence at ≥ 11 points. No significant difference was found between groups in patients with Child scores of 8 to 10 points.

TIPS placement for recurrent tense ascites is associated with an increased rate of ACLF in patients with severely impaired liver function but does not result in higher in-hospital mortality.

Core Tip: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is an effective therapy for recurrent tense ascites, but there are concerns about further deterioration of liver function in patients with advanced cirrhosis. We retrospectively analyzed 214 patients receiving TIPS for ascites and compared their outcomes to matched conservatively treated patients. We found that TIPS can trigger acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) in patients with severely impaired liver function. However, no increased mortality was found compared to conservatively treated patients. Despite an increased risk of ACLF, TIPS is a viable option for patients with ascites and hepatic impairment.

- Citation: Philipp M, Blattmann T, Bienert J, Fischer K, Hausberg L, Kröger JC, Heller T, Weber MA, Lamprecht G. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt vs conservative treatment for recurrent ascites: A propensity score matched comparison. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(41): 5944-5956

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i41/5944.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i41.5944

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is an effective therapy for complications of portal hypertension, such as ascites or esophageal variceal bleeding. Although TIPS placement is effective against ascites, early studies showed no survival benefit after TIPS placement compared to repeated paracentesis and albumin substitution[1-3]. More recent studies have shown more promising results, such as survival benefit[4-7], improved renal function[8,9] and better quality of life[10,11]. TIPS placement is therefore recommended as the treatment of choice[12,13].

Nevertheless, TIPS placement is an invasive procedure with considerable risks. In addition to hepatic encephalopathy and bleeding complications due to the placement procedure, sudden worsening of liver function is a serious complication. It has been observed after 5% to 10% of TIPS procedures and has a serious prognosis[14,15]. Such an acute deterioration of liver function accompanied by single- or multi-organ-failure is a common complication of advanced liver cirrhosis. This clinical syndrome has been described as acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF)[16]. Due to the risk of liver failure, TIPS placement for ascites is often limited to patients with good liver function and most randomized controlled trials have been conducted in patients with good liver function. It is still unclear how often ACLF occurs after TIPS placement and whether it is due to the TIPS procedure or rather to the severity of the underlying liver disease[17]. Recent recommendations argue against strict cut-off values for MELD, Child or other scoring systems. Instead, they recommend individual decision-making[18]. To better address the risk of ACLF in this challenging clinical situation the aim of this study was: (1) To determine whether ACLF occurs more often in patients with recurrent tense ascites treated with TIPS than in patients receiving conservative therapy; (2) to compare the outcome of ACLF associated with TIPS placement with the outcome of ACLF in patients receiving conservative therapy; and (3) to evaluate whether the risk of ACLF and death associated with TIPS placement increases disproportionately in patients with marginal liver function.

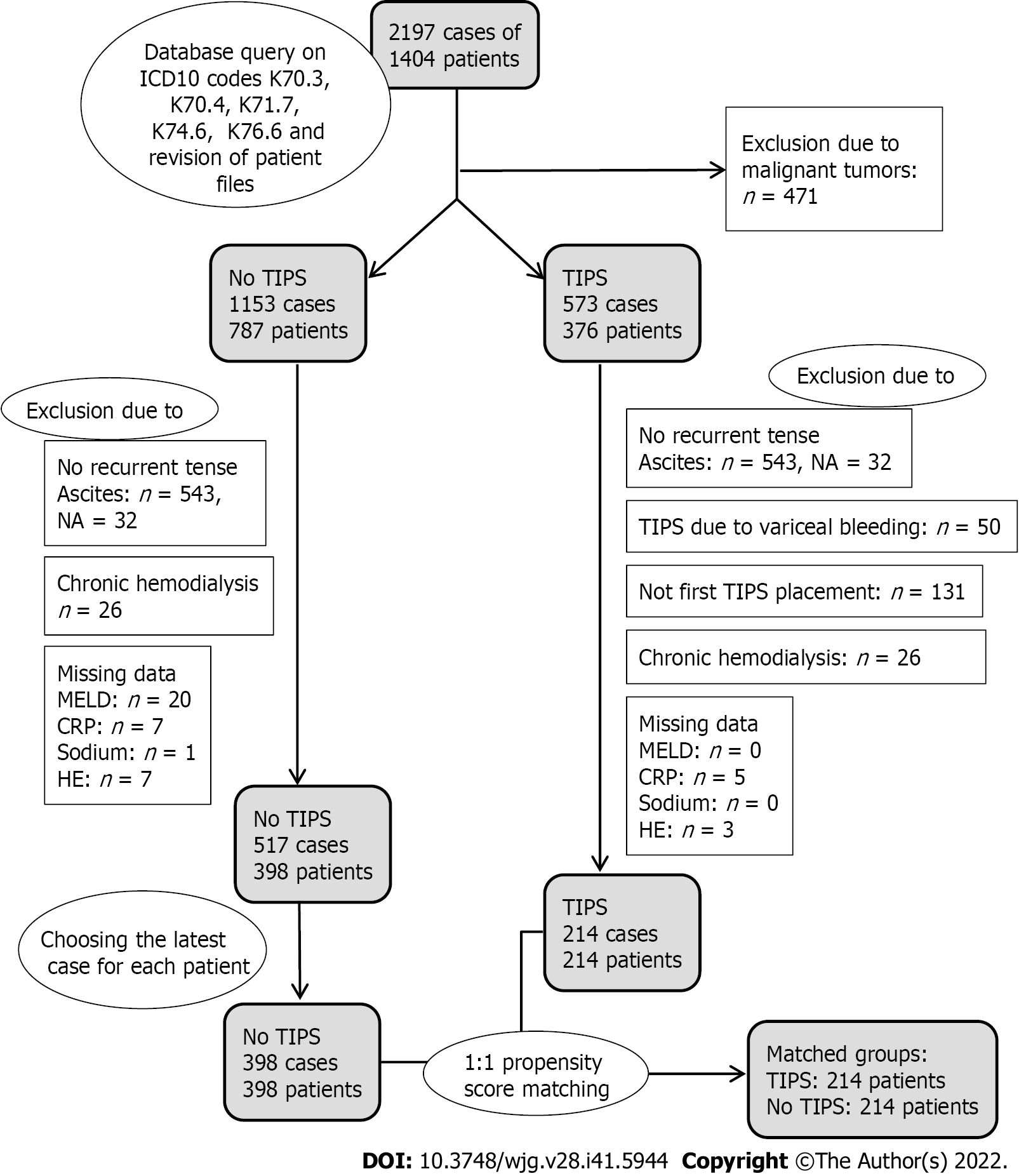

A database was constructed containing ICD and OPS codes as well as laboratory values of all inpatients of the Division of Gastroenterology of the Rostock University Medical Center. Patients who were treated for liver cirrhosis between 2007 and 2017 were identified based on their discharge diagnosis using ICD10 codes K70.3, K70.4, K71.7, K74.6 and K76.6 (2197 cases of 1404 patients). Patients who received TIPS were identified using OPS codes 8-839*. Only cases of patients receiving their first TIPS for recurrent tense ascites were selected. Therefore there was only one case per patient in the TIPS group. Cases of patients who had liver cirrhosis and tense ascites requiring paracentesis, but did not undergo TIPS placement were selected for comparison (No TIPS group). If several cases were available for the same patient in the No TIPS group (e.g., because of multiple hospital admissions), the latest case was selected. TIPS indication, diagnosis of recurrent tense ascites, further diagnoses and clinical findings were obtained from ICD codes and from patient files. Laboratory values were obtained from the data base. Cases with missing data on relevant clinical or laboratory findings were removed (43 cases). Cases with pre-existing renal insufficiency requiring dialysis (30 cases) or with malignant tumors (471 cases) were also excluded. Patient selection resulted in 398 patients in the No TIPS group and 214 patients in the TIPS group. After data collection was completed, all patient data were pseudonymized. Patient selection criteria and reasons for exclusion from data analysis are depicted in Figure 1. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Rostock University Medical Center (A2018-0127).

The MELD-score and ACLF grade as defined by Moreau et al[16] at hospital admission and the highest ACLF grade achieved during hospital stay were determined for each patient. Furthermore, the in-hospital mortality of both groups was determined. Multivariate logistic regressions revealed that bilirubin, creatinine, INR, CRP, sodium, white blood cell count, albumin and age were predictive either for survival or for group membership in TIPS vs No TIPS group or for both. Therefore these covariates were chosen for the propensity score matching procedure. The matching (1:1 greedy matching, nearest neighbor, without replacement) resulted in a matched sample of 428 patients (214 patients in the No TIPS and 214 in the TIPS group).

Statistical evaluation and matching were carried out using R (R version 3.6.3[19] and the R Package MatchIt, Version 4.1.0[20]). The distribution of most of the continuous data had significant positive skew, therefore non-parametric test methods were used. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and categorical variables using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Data on an ordinal scale (ACLF, hepatic encephalopathy) were treated as continuous. To account for the loss of statistical independence due to the matching procedure[21,22], comparisons between the matched groups were carried out using the Wilcoxon signed rank test or McNemar test. Additional multivariate logistic regressions were performed as sensitivity analysis and for further insights into effects of liver function, TIPS placement and their interaction on ACLF incidence and in-hospital mortality. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Henrik Rudolf from Rostock University Medical Center, Institute for Biostatistics and Informatics in Medicine and Ageing Research.

Patient demographics and liver disease characteristics of the unmatched cohort are summarized in Table 1. Continuous values are given as median and range, categorical values as total number and percentage. Patients receiving TIPS had better liver function as assessed by MELD and Child score, bilirubin, INR, albumin and severity of hepatic encephalopathy. In addition, CRP, platelets and leukocytes differed significantly. Creatinine did not differ significantly. After propensity score matching all covariates were balanced in both groups (Table 2) and all variables used for matching did no longer predict group membership in the matched patients.

| Characteristics | No TIPS | TIPS | P value |

| Patients | 398 | 214 | |

| Male | 269 (68%) | 153 (71%) | 0.320 |

| Age (yr) | 59.5 (26.4-93.4) | 59.1 (29.9-80.7) | 0.190 |

| Cause of cirrhosis | 0.130 | ||

| -Alcohol | 305 (77%) | 179 (84%) | |

| -Viral hepatitis | 11 (3%) | 4 (2%) | |

| -Other | 82 (21%) | 31 (14%) | |

| Child points (min-max) | 10 (7-15) | 9 (7-14) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (West-Haven) | 0.040 | ||

| -None | 276 (69%) | 165 (77%) | |

| -Grade 1-2 | 73 (18%) | 30 (14%) | |

| -Grade 3-4 | 49 (12%) | 19 (9%) | |

| ACLF grade at hospital admission | 0.020 | ||

| -No ACLF | 294 (74%) | 173 (81%) | |

| -ACLF grade 1 | 64 (16%) | 39 (18%) | |

| -ACLF grade 2 | 32 (8%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| -ACLF grade 3 | 8 (2%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| -Meld | 18 (7-40) | 14 (7-40) | < 0.001 |

| -Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 49.7 (5.9-668.0) | 28.1 (6.1-688.5) | < 0.001 |

| -Creatinine (μmol/L) | 100.5 (23.1-781.0) | 107.0 (42.3-783.5) | 0.180 |

| -INR | 1.45 (0.92-9.2) | 1.28 (0.97-2.5) | < 0.001 |

| -Sodium (μmol/L) | 134 (106-149) | 133 (115-146) | 0.760 |

| -Albumin (g/L) | 22.6 (7.9-48.7); NA: 55 | 26.1 (11.0-39.6); NA: 23 | < 0.001 |

| -CRP (mg/L) | 25.6 (1.0-283.0) | 18.0 (2.0-181.0) | < 0.001 |

| -Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | 6.8 (2.0-9.8) | 6.7 (3.4-10.0) | 0.310 |

| -Platelets (Gpt/L) | 134.5 (22.0-715.0) | 153.5 (13.0-668.0) | 0.002 |

| -Leucocytes (Gpt/L) | 8.76 (1.34-44.90) | 7.34 (2.72-33.20) | < 0.001 |

| Characteristics | No TIPS | TIPS | P value |

| Patients | 214 | 214 | |

| Male | 142 (66%) | 153 (71%) | 0.30 |

| Age (yr) | 59.4 (26.4-93.4) | 59.1 (29.9-80.7) | 0.14 |

| Cause of cirrhosis | 0.26 | ||

| -Alcohol | 163 (76%) | 179 (84%) | |

| -Viral hepatitis | 8 (4%) | 4 (2%) | |

| -Other | 43 (20%) | 31 (14%) | |

| Child points (min-max) | 9 (7-14) | 9 (7-14) | 0.76 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (west-haven) | 0.65 | ||

| -None | 173 (81%) | 165 (77%) | |

| -Grade 1-2 | 22 (10%) | 30 (14%) | |

| -Grade 3-4 | 19 (9%) | 19 (9%) | |

| ACLF grade at hospital admission | 0.37 | ||

| -No ACLF | 176 (82%) | 173 (81%) | |

| -AACLF 1 | 36 (17%) | 39 (18%) | |

| -ACLF 2 | 2 (1%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| -ACLF 3 | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| -Meld | 14 (7-36) | 14 (7-40) | 0.97 |

| -Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 29.7 (5.9-261.0) | 28.1 (6.1-688.5) | 0.10 |

| -Creatinine (μmol/L) | 90.9 (23.1-781.0) | 107.0 (42.3-783.5) | 0.08 |

| -INR | 1.32 (0.92-2.41) | 1.28 (0.97-2.50) | 0.28 |

| -Sodium (mmol/L) | 135 (106-144) | 133 (115-146) | 0.10 |

| -Albumin (g/L) | 24.3 (7.9-48.7); NA: 27 | 26.1 (11.0-39.6); NA: 23 | 0.61 |

| -CRP (mg/L) | 18.7 (1.0-283.0) | 18.0 (2.0-181.0) | 0.10 |

| -Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | 6.8 (2.1-9.8) | 6.7 (3.4-10.0) | 0.43 |

| -Platelets (Gpt/L) | 141.0 (23.0-715.0) | 154.0 (13.0-668.0) | 0.08 |

| -Leucocytes (Gpt/L) | 7.58 (1.34-44.90) | 7.34 (2.72-33.20) | 0.98 |

From 2007 to 2017, both covered and uncovered stents were used for TIPS at our institution. Uncovered stents were placed in 42% and covered stents in 58% of cases. Stents were mostly dilated to 7-8 mm. Smaller or larger diameters were rarely chosen (6mm in 2 patients, 9 or 10 mm in 15 patients). No effect of stent type or stent diameter on any of our endpoints was found in either univariate or multivariate analyses (data not shown).

Table 3 shows the incidence of ACLF as well as the in-hospital mortality of the matched patients. Patients receiving TIPS more often had ACLF of any grade (TIPS: 70/214 patients vs No TIPS 57/214 patients) and achieved higher ACLF grades (P = 0.04). An increase in ACLF grade (as compared to the ACLF grade at hospital admission) was more common in the TIPS group than in the No TIPS group (in 38/214 patients vs 23/214 patients). The hospital stay was longer in the TIPS group. The majority of patients in both groups had ACLF 1, which was due to renal failure. Organ systems affected in patients with ACLF > 1 were brain (hepatic encephalopathy grade 3-4) and/or liver function based on bilirubin in addition to renal failure. ACLF > 1 was mostly due to acute infections.

| Event | No TIPS | TIPS | P value/OR (95%CI) |

| Hospital stay (d) | 10 (1-78) | 14 (3-64) | P < 0.001 |

| Highest ACLF grade | P = 0.041 | ||

| -No ACLF | 157 (73%) | 144 (67%) | |

| -ACLF 1 | 47 (22%) | 50 (23%) | |

| -ACLF 2 | 8 (4%) | 15 (7%) | |

| -ACLF 3 | 2 (1%) | 5 (2%) | |

| -Any ACLF | 57 (27%) | 70 (33%) | |

| Mortality by ACLF | |||

| -Over all | 13/214 (6.1%) | 11/214 (5.1%) | OR: 0.84 (0.33 -2.08) |

| -No ACLF | 3/157 (1.9%) | 0/144 (0%) | OR: 0 (0.00 -2.63) |

| -ACLF 1 | 3/47 (6.4%) | 4/50 (8%) | OR: 1.27 (0.20 -9.18) |

| -ACLF 2 | 6/8 (75%) | 3/15 (20%) | OR: 0.09 (0.01 -0.87) |

| -ACLF 3 | 1/2 (50%) | 4/5 (80%) | OR: 3.16 (0.03 -389.17) |

| -Any ACLF | 10/57 (17.5%) | 11/70 (15.7%) | OR: 0.88 (0.31-2.52) |

| Increase in ACLF grade | P = 0.03 | ||

| -No increase | 191 (89.3%) | 176 (82.2%) | |

| -1 grade | 18 (8.4%) | 28 (13.1%) | |

| -2 grades | 4 (1.9%) | 7 (3.3%) | |

| -3 grades | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.4%) | |

| Mortality by ACLF increase | |||

| -No increase | 5/191 (2.6%) | 2/176 (1.1%) | OR: 0.43 (0.04-2.66) |

| -1 grade | 4/18 (22.2%) | 5/28 (17.9%) | OR: 0.77 (0.14-4.55) |

| -2 grades | 3/4 (75.0%) | 2/7 (20.0%) | OR: 0.16 (0.003-3.50) |

| -3 grades | 1/1 (100%) | 2/3 (66.7%) | OR: 0 (0.00-116.8) |

| -Any increase | 8/23 (34.8%) | 9/38 (23.7%) | OR: 0.58 (0.16-2.14) |

There was no difference in terms of in-hospital mortality. In the TIPS group 11 of 214 patients died, in the No TIPS group 13 of 214 patients died. The mortality increased with the ACLF grade in both groups. Multivariate logistic regressions were performed as a sensitivity analysis and confirmed that TIPS was a risk factor for ACLF but not for in-hospital mortality (Table 4). Mortality in any ACLF stratum except ACLF 2 was comparable in both groups. For patients with ACLF 2, we found a lower mortality in the TIPS group compared to the No TIPS group (OR 0.09, 95%CI 0.01-0.87). The mortality of TIPS patients who increased in ACLF by 2 or 3 grades after TIPS placement was high (4/10 died). This also applies to the No TIPS group with an even higher mortality (4/5 patients with an increase of 2 or 3 ACLF grades compared to ACLF grade at hospital admission died).

| Variable | Estimate | SE | P value | Estimate | SE | P value |

| Complete model | Best model | |||||

| Mortality | ||||||

| Intercept | 3.63 | 3.27 | 0.268 | 4.39 | 3.22 | 0.173 |

| Creatinine | 1.59 × 10-3 | 1.37 × 10-3 | 0.246 | 1.99 × 10-3 | 1.32 × 10-3 | 0.132 |

| Bilirubin | 7.26 × 10-4 | 1.10 × 10-3 | 0.505 | - | - | - |

| INR | 3.49 × 10-1 | 2.15 × 10-1 | 0.104 | 3.47 × 10-1 | 2.12 × 10-1 | 0.101 |

| CRP | 3.27 × 10-3 | 3.10 × 10-3 | 0.292 | - | - | - |

| Leucocytes | 7.01 × 10-2 | 2.64 × 10-2 | 0.008 | 7.84 × 10-2 | 2.53 × 10-2 | 0.002 |

| HE 1-2 | -2.88 × 10-1 | 4.28 × 10-1 | 0.500 | -2.67 × 10-1 | 4.1 × 10-1 | 0.523 |

| HE 3-4 | 2.24 | 3.56 × 10-1 | < 0.001 | 2.26 | 3.50 × 10-1 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin | -9.61 × 10-2 | 2.76 × 10-2 | < 0.001 | -1.02 × 10-1 | 2.72 × 10-2 | < 0.001 |

| Sodium | -6.21 × 10-2 | 2.45 × 10-2 | 0.011 | -6.51 × 10-2 | 2.45 × 10-2 | 0.004 |

| Age | 1.22 × 10-4 | 4.24 × 10-5 | 0.004 | 1.16 × 10-4 | 4.04 × 10-5 | 0.004 |

| TIPS | -7.29 × 10-1 | 4.12 × 10-1 | 0.077 | -8.22 × 10-1 | 4.01 × 10-1 | 0.040 |

| ACLF | ||||||

| Intercept | -1.822 | 2.713 | 0.502 | -2.70 | 8.51 × 10-1 | 0.002 |

| Creatinine | -1.06 × 10-3 | 1.21 × 10-3 | 0.384 | - | - | - |

| Bilirubin | 2.81 × 10-3 | 9.50 × 10-4 | 0.003 | 2.99 × 10-3 | 8.69 × 10-4 | 0.001 |

| INR | 2.16 × 10-1 | 2.01 × 10-1 | 0.281 | - | - | - |

| CRP | 5.21 × 10-3 | 2.58 × 10-3 | 0.043 | 4.67 × 10-3 | 2.39 × 10-3 | 0.050 |

| Leucocytes | 6.28 × 10-3 | 2.43 × 10-2 | 0.780 | - | - | - |

| HE 1-2 | 1.22 × 10-1 | 3.06 × 10-1 | 0.690 | 1.47 × 10-1 | 3.02 × 10-1 | 0.627 |

| HE 3-4 | 1.62 | 3.01 × 10-1 | < 0.001 | 1.63 | 2.94 × 10-1 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin | -3.80 × 10-2 | 2.00 × 10-2 | 0.058 | -3.98 × 10-2 | 1.99 × 10-2 | 0.046 |

| Sodium | -1.03 × 10-2 | 1.98 × 10-2 | 0.603 | - | - | - |

| Age | 6.39 × 10-5 | 3.11 × 10-5 | 0.039 | 5.63 × 10-5 | 2.96 × 10-5 | 0.057 |

| TIPS | 5.17 × 10-1 | 2.64 × 10-1 | 0.050 | 4.39 × 10-1 | 2.55 × 10-1 | 0.085 |

Most patients in both groups (No TIPS 89%, TIPS 82%) without ACLF at admission did not develop any ACLF during hospital stay. Many patients who developed an ACLF grade 2 or 3 already had ACLF at hospital admission (5/10 patients in the No TIPS group and 11/20 patients in the TIPS group). Three patients in the TIPS group developed ACLF during the period between hospital admission and TIPS placement, i.e. before TIPS was implanted. Many of the pre-TIPS ACLFs resolved after TIPS placement. When comparing the highest ACLF grade before TIPS to the ACLF grade at hospital discharge (assuming ACLF 3 for patients who died), 32 patients (15%) improved their ACLF grade after TIPS placement while only 21 patients (10%) had a worse ACLF grade at discharge than at the time of TIPS placement.

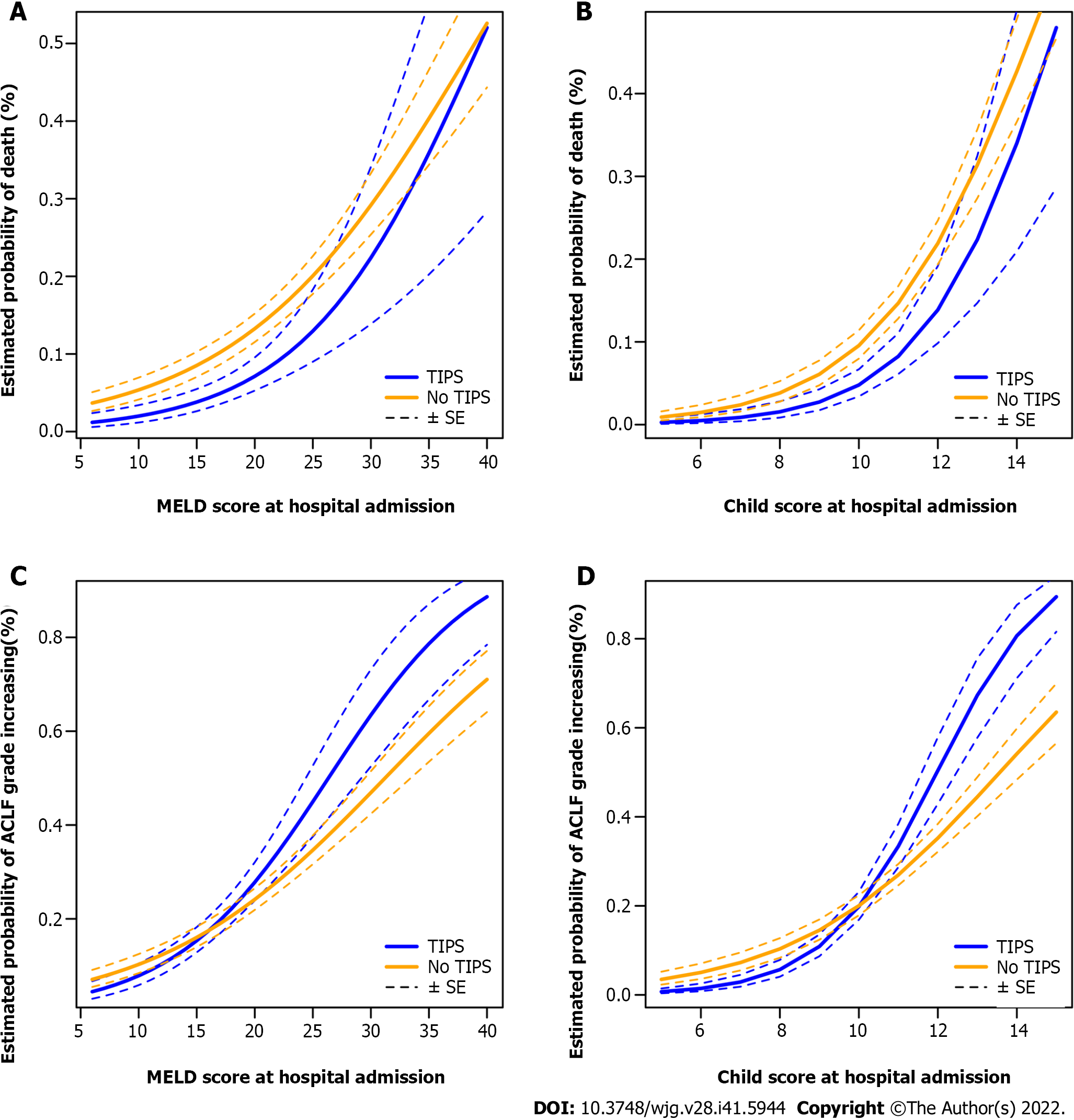

Using multivariate logistic regression models based on the MELD or Child scores at admission, the probabilities of death in-hospital and of an increase in ACLF grade were estimated for the TIPS and the No TIPS group (Figure 2). The likelihood of death increases with the severity of the disease at admission; independent of whether this is assessed by MELD or by Child scores (Figure 2A and B). The regression curves for mortality are almost parallel, indicating that mortality depends only on liver function, but not on TIPS placement or an interaction between TIPS placement and the liver function. However, the regression curves for an increase in ACLF grade differ clearly between TIPS and No TIPS (Figure 2C and D). The probability of an ACLF in the TIPS group is lower than in the No TIPS group at low to moderate MELD-and Child-levels, but it is higher than in the No TIPS group at high MELD and Child scores. The intersection of the regression curves suggests an interaction between MELD/Child score and TIPS placement. In fact, the multivariate logistic regression shows a statistically significant interaction term for Child-score and TIPS (P = 0.03; Table 5). In our model the TIPS group has a lower ACLF incidence at Child scores lower than 8 points and a higher ACLF incidence at 11 points and higher. Between 8 and 11 points the standard errors of both groups overlap, indicating that there is no relevant difference between both groups. The same effect can be observed when using the MELD score instead of the Child score. However, the interaction is weaker and not statistically significant (P = 0.19).

| Model | Dependent variable | Parameters | Estimate | SE | z value | P value |

| A | Intercept | -3.8600 | 0.4340 | -8.887 | < 2 × 10-16 | |

| In-hospital | MELD-Score | 0.0990 | 0.0180 | 5.628 | 1.82 × 10-8 | |

| Mortality (y/n) | TIPS | -1.3570 | 1.0590 | -1.281 | 0.200 | |

| MELD: TIPS | 0.0330 | 0.0500 | 0.668 | 0.504 | ||

| B | Intercept | -7.1320 | 0.9810 | -7.271 | 3.56 × 10-13 | |

| In-hospital | Child (points) | 0.4880 | 0.0840 | 5.814 | 6.09 × 10-9 | |

| Mortality (y/n) | TIPS | -1.6760 | 2.2350 | -0.750 | 0.453 | |

| Child: TIPS | 0.0934 | 0.2020 | 0.463 | 0.643 | ||

| C | Intercept | -3.1860 | 0.3610 | -8.824 | < 2 × 10-16 | |

| Increase in | MELD | 0.1020 | 0.0160 | 6.461 | 1.04 × 10-10 | |

| ACLF grade | TIPS | -0.7780 | 0.7120 | -1.092 | 0.275 | |

| (y/n) | MELD: TIPS | 0.0480 | 0.0368 | 1.318 | 0.187 | |

| D | Intercept | -5.2640 | 0.7480 | -7.040 | 1.93 × 10-12 | |

| Increase in | Child (points) | 0.3880 | 0.0670 | 5.807 | 6.37 × 10-9 | |

| ACLF grade | TIPS | -3.1980 | 1.5300 | -2.090 | 0.0366 | |

| (y/n) | Child: TIPS | 0.3190 | 0.1145 | 2.191 | 0.0285 |

Most of the randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been performed in patients with good liver function. This applies in particular to the RCTs that showed a survival benefit. In these studies the mean MELD was 9.6[6] to 12.1[7]). Therefore many patients with refractory ascites receive no TIPS due to impaired liver function. Others have considered MELD scores ≥ 18[13,23,24] to ≥ 24[25,26] and bilirubin levels ≥ 51.3 to ≥ 85.5 μmol/L[13,27] as contraindications for TIPS. Our TIPS patients had a comparatively poor liver function at hospital admission (MELD median 14, mean 15.2), allowing to describe mortality and morbidity in this high-risk group.

In our cohort of patients with significantly impaired liver function ACLF incidence and in-hospital mortality was within the range observed in other studies on ACLF[16,28,29]. The in-hospital mortality was neither positively nor negatively influenced by TIPS placement despite the comparatively poor liver function of our patients. In the matched cohorts ACLF occurred more frequently in the TIPS group than in conservatively treated patients. The results of the multivariate logistic regressions suggest that this effect depends on the extent of the pre-existing liver damage. In patients with good liver function (Child ≤ 8) an ACLF occurs less frequently in the TIPS group. However, at higher scores (Child ≥ 11), the probability of developing an ACLF is higher in the TIPS group than in the No TIPS group. This interaction blurs the effect of TIPS on ACLF incidence in univariate analyses.

Not all ACLFs in the TIPS group can be attributed to TIPS. The majority of the ACLFs occurred already before TIPS placement and many patients already had at least an ACLF grade 1 on hospital admission. ACLFs grade 1 were almost exclusively due to renal failure. This was to be expected in patients with recurrent tense ascites. Patients whose ACLF increased by 2 or 3 grades during hospital stay had a particularly poor outcome in both groups. A serious deterioration of liver function after TIPS placement is often attributed to TIPS placement. In our patients such events occurred in both groups when we considered the entire hospital stay (No TIPS group 5/214 patients, TIPS group 10/214 patients). Some of the ACLFs after TIPS placement are likely due to other causes than TIPS, such as bacterial infections or gastrointestinal bleeding. Such events precede most ACLFs and can occur with and without TIPS placement[29]. In line with that, TIPS was not a precipitant of ACLF in a recently published study on acute decompensation and ACLF[28]. Furthermore, the majority of pre-TIPS ACLFs resolved after TIPS placement, suggesting that TIPS is more capable to overcome an ACLF than causing it. We have studied patients with recurrent tense ascites. The most common cause of ACLF within this group was kidney failure. It is plausible that a TIPS can improve such an ACLF, e.g., since dose of diuretics can be lowered or diuretics can be discontinued altogether.

We did not include an analysis of the effect of TIPS on ascites resolution since it typically takes up to several months after TIPS placement for the underlying circulatory, renal and neurohumoral dysfunction to normalize[27]. Therefore, the effect of TIPS placement on ascites cannot be reliably assessed during hospital stay.

When interpreting these results, the limitations of a retrospective analysis have to be considered. Since this is a retrospective study, many patients in the No TIPS group lack data on the further course after hospital discharge. For the selected endpoints (highest ACLF during inpatient stay, death during inpatient stay), complete data are available in both groups. Therefore, we had to limit the analysis to inpatient stay. In this study propensity score matching was used prior to comparing the TIPS and No TIPS group. However, even with propensity score matching, a similar distribution of unknown confounders cannot be guaranteed. We only evaluated the short-term outcome during hospital stay. It is well known that the positive impact of a TIPS only takes effect after a few weeks to months[23,27]. In fact, some studies have observed an increased mortality after TIPS placement during the first few weeks[24,30]. Therefore, positive effects of TIPS on survival might be underestimated. On the other hand, our results were confirmed and extended by the multivariate logistic regressions (Table 5). The multivariate logistic regression also provided insight into the complex interactions between liver function and TIPS as seen in Figure 2.

Some ACLFs were already present on admission, some occurred before TIPS, and some ACLFs improved after TIPS. The fact that some patients already had ACLF prior to TIPS complicates the interpretation of the relationship between TIPS and ACLF. As in all retrospective studies, conclusions about the causal relationship between ACLF and TIPS are impossible. Furthermore, we cannot analyze systematically why TIPS was chosen in some patients and not in others. We can only compare the clinical outcome of both groups after very careful propensity score matching.

Our TIPS patients had a comparatively poor liver function, but a bilirubin of 85.5 μmol/L or a MELD of 24 points was rarely exceeded (approx. 8% and 6% of patients). In addition, in patients with very high MELD scores on hospital admission, TIPS placement was performed only after initial stabilization and after MELD had improved. Since the number of observations in our study is limited for this situation, a decision for TIPS placement should be made with caution in such patients. Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 2 and in accordance with other studies the mortality in the TIPS group is not higher than in the No TIPS group even at the highest MELD and Child scores[17,31-33].

Our data show an increased risk of ACLF in the TIPS group in patients with severely impaired liver function (Child ≥ 11 points), but not in patients with good or moderately impaired liver function. These findings may explain why TIPS is often considered a risky intervention with potentially unfavorable outcomes in patients with high MELD or Child scores. Nevertheless, we did not find such a negative effect of TIPS placement on in-hospital mortality in patients with high to very high MELD and Child scores. We found that many ACLFs in the TIPS group occurred before TIPS placement and often resolved after TIPS placement. Unlike several previous RCTs we did not find a positive effect of TIPS on mortality. Possible reasons are the comparatively short follow-up and the significantly worse liver function of our TIPS patients compared to the patients in the RCTs. In the presence of moderately to severely impair liver function recurrent tense ascites may be a dominant symptom. TIPS is the most effective therapy for recurrent tense ascites. Therefore, we conclude that TIPS is a viable option not only for patients with good liver function but also for patients with high Child scores after carefully weighing the increased risk of ACLF against the expected benefits.

TIPS placement for recurrent tense ascites is associated with an increased incidence of ACLF. This effect occurs only in patients with severely impaired liver function (Child score ≥ 11) and does not lead to a higher in-hospital mortality compared with conservative treatment.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is an effective treatment for recurrent tense ascites. Acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) of various severities is a serious complication usually causally attributed to TIPS placement. But the potential of TIPS to improve ACLF grade 1 and 2, which is mostly related to acute kidney injury in these patients, may be underestimated.

TIPS placement for recurrent tense ascites may be beneficial even in patients with severely impaired liver and kidney function. But the exact medical limits need further clarification.

To retrospectively evaluate the in-hospital mortality of patients with recurrent tense ascites and reduced liver function-including severely reduced liver function-undergoing TIPS placement (TIPS group) and to compare these data to a carefully matched cohort with recurrent tense ascites receiving conservative treatment (No TIPS group). To better address the clinical scenario not only the time after TIPS placement but the entire hospital stays was analyzed.

Two hundred and twenty-four patients undergoing TIPS placement for recurrent tense ascites were retrospectively compared to an equal number of propensity score matched, conservatively treated patients. Primary objectives were in-hospital mortality and the development or worsening or improvement of ACLF. Additional multivariate logistic regressions were performed as sensitivity analysis and for further insights into effects of liver function, TIPS placement and their interaction on ACLF incidence and in-hospital mortality.

TIPS placement did not result in an increased in-hospital mortality compared to the matched cohort. ACLF incidence in the TIPS group depended on liver function: At Child-Pugh-Scores < 8 TIPS reduced the risk of ALCF development, at scores of 8 to 10 ACLF risk did not differ between TIPS and No TIPS, and at scores ≥ 11 TIPS increased the risk of ALCF. Many preexisting ACLFs grade 1 resolved after TIPS placement. The relevant prognostic parameters for this need further elucidation. The data point to a biologic interaction of liver function and TIPS placement with regard to the development of ACLF, which needs further evaluation.

In selected patients with severely impaired liver function TIPS placement does not result in an increased in-hospital mortality compared to conservatively treated patients. TIPS was associated with ALCF only in patients with severely impaired liver function (Child > 11 points).

The medical limits of TIPS placement for recurrent tense ascites should be evaluated in prospective studies which need to address the indications, contraindications and the associated complex decision making.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Germany

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferrarese A, Italy; Luo FX, China; Mucenic M, Brazil; Zaghloul MS, Egypt; Zhu YY, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Lebrec D, Giuily N, Hadengue A, Vilgrain V, Moreau R, Poynard T, Gadano A, Lassen C, Benhamou JP, Erlinger S. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: comparison with paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites: a randomized trial. French Group of Clinicians and a Group of Biologists. J Hepatol. 1996;25:135-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ginès P, Uriz J, Calahorra B, Garcia-Tsao G, Kamath PS, Del Arbol LR, Planas R, Bosch J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting versus paracentesis plus albumin for refractory ascites in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1839-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sanyal AJ, Genning C, Reddy KR, Wong F, Kowdley KV, Benner K, McCashland T; North American Study for the Treatment of Refractory Ascites Group. The North American Study for the Treatment of Refractory Ascites. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:634-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rössle M, Ochs A, Gülberg V, Siegerstetter V, Holl J, Deibert P, Olschewski M, Reiser M, Gerbes AL. A comparison of paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1701-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Salerno F, Merli M, Riggio O, Cazzaniga M, Valeriano V, Pozzi M, Nicolini A, Salvatori F. Randomized controlled study of TIPS versus paracentesis plus albumin in cirrhosis with severe ascites. Hepatology. 2004;40:629-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Narahara Y, Kanazawa H, Fukuda T, Matsushita Y, Harimoto H, Kidokoro H, Katakura T, Atsukawa M, Taki Y, Kimura Y, Nakatsuka K, Sakamoto C. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus paracentesis plus albumin in patients with refractory ascites who have good hepatic and renal function: a prospective randomized trial. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:78-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bureau C, Thabut D, Oberti F, Dharancy S, Carbonell N, Bouvier A, Mathurin P, Otal P, Cabarrou P, Péron JM, Vinel JP. Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunts With Covered Stents Increase Transplant-Free Survival of Patients With Cirrhosis and Recurrent Ascites. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Allegretti AS, Ortiz G, Cui J, Wenger J, Bhan I, Chung RT, Thadhani RI, Irani Z. Changes in Kidney Function After Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunts Versus Large-Volume Paracentesis in Cirrhosis: A Matched Cohort Analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:381-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Busk TM, Bendtsen F, Poulsen JH, Clemmesen JO, Larsen FS, Goetze JP, Iversen JS, Jensen MT, Møgelvang R, Pedersen EB, Bech JN, Møller S. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: impact on systemic hemodynamics and renal and cardiac function in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;314:G275-G286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Campbell MS, Brensinger CM, Sanyal AJ, Gennings C, Wong F, Kowdley KV, McCashland T, Reddy KR. Quality of life in refractory ascites: transjugular intrahepatic portal-systemic shunting versus medical therapy. Hepatology. 2005;42:635-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gülberg V, Liss I, Bilzer M, Waggershauser T, Reiser M, Gerbes AL. Improved quality of life in patients with refractory or recidivant ascites after insertion of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Digestion. 2002;66:127-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1777] [Cited by in RCA: 1803] [Article Influence: 257.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, China L, Härmälä S, Macken L, Ryan JM, Wilkes EA, Moore K, Leithead JA, Hayes PC, O'Brien AJ, Verma S. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut. 2021;70:9-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bettinger D, Schultheiss M, Boettler T, Muljono M, Thimme R, Rössle M. Procedural and shunt-related complications and mortality of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1051-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Luca A, Miraglia R, Maruzzelli L, D'Amico M, Tuzzolino F. Early Liver Failure after Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt in Patients with Cirrhosis with Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Score of 12 or Less: Incidence, Outcome, and Prognostic Factors. Radiology. 2016;280:622-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, Durand F, Gustot T, Saliba F, Domenicali M, Gerbes A, Wendon J, Alessandria C, Laleman W, Zeuzem S, Trebicka J, Bernardi M, Arroyo V; CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426-1437, 1437.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1720] [Cited by in RCA: 2162] [Article Influence: 180.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 17. | Ronald J, Rao R, Choi SS, Kappus M, Martin JG, Sag AA, Pabon-Ramos WM, Suhocki PV, Smith TP, Kim CY. No Increased Mortality After TIPS Compared with Serial Large Volume Paracenteses in Patients with Higher Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Score and Refractory Ascites. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:720-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Boike JR, Thornburg BG, Asrani SK, Fallon MB, Fortune BE, Izzy MJ, Verna EC, Abraldes JG, Allegretti AS, Bajaj JS, Biggins SW, Darcy MD, Farr MA, Farsad K, Garcia-Tsao G, Hall SA, Jadlowiec CC, Krowka MJ, Laberge J, Lee EW, Mulligan DC, Nadim MK, Northup PG, Salem R, Shatzel JJ, Shaw CJ, Simonetto DA, Susman J, Kolli KP, VanWagner LB; Advancing Liver Therapeutic Approaches (ALTA) Consortium. North American Practice-Based Recommendations for Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunts in Portal Hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1636-1662.e36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dean CB, Nielsen JD. Generalized linear mixed models: a review and some extensions. Lifetime Data Anal. 2007;13:497-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. MatchIt: Nonparametric Preprocessing for Parametric Causal Inference. J Stat Softw. 2011;42. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1461] [Cited by in RCA: 1462] [Article Influence: 104.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6382] [Cited by in RCA: 7449] [Article Influence: 532.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 6th ed. Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education 2014: 516. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Rössle M. TIPS: 25 years later. J Hepatol. 2013;59:1081-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gaba RC, Parvinian A, Casadaban LC, Couture PM, Zivin SP, Lakhoo J, Minocha J, Ray CE Jr, Knuttinen MG, Bui JT. Survival benefit of TIPS versus serial paracentesis in patients with refractory ascites: a single institution case-control propensity score analysis. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:e51-e57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Montgomery A, Ferral H, Vasan R, Postoak DW. MELD score as a predictor of early death in patients undergoing elective transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:307-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Burgos AC, Thornburg B. Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Placement for Refractory Ascites: Review and Update of the Literature. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018;35:165-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rössle M, Gerbes AL. TIPS for the treatment of refractory ascites, hepatorenal syndrome and hepatic hydrothorax: a critical update. Gut. 2010;59:988-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Trebicka J, Fernandez J, Papp M, Caraceni P, Laleman W, Gambino C, Giovo I, Uschner FE, Jansen C, Jimenez C, Mookerjee R, Gustot T, Albillos A, Bañares R, Jarcuska P, Steib C, Reiberger T, Acevedo J, Gatti P, Shawcross DL, Zeuzem S, Zipprich A, Piano S, Berg T, Bruns T, Danielsen KV, Coenraad M, Merli M, Stauber R, Zoller H, Ramos JP, Solé C, Soriano G, de Gottardi A, Gronbaek H, Saliba F, Trautwein C, Kani HT, Francque S, Ryder S, Nahon P, Romero-Gomez M, Van Vlierberghe H, Francoz C, Manns M, Garcia-Lopez E, Tufoni M, Amoros A, Pavesi M, Sanchez C, Praktiknjo M, Curto A, Pitarch C, Putignano A, Moreno E, Bernal W, Aguilar F, Clària J, Ponzo P, Vitalis Z, Zaccherini G, Balogh B, Gerbes A, Vargas V, Alessandria C, Bernardi M, Ginès P, Moreau R, Angeli P, Jalan R, Arroyo V; PREDICT STUDY group of the EASL-CLIF CONSORTIUM. PREDICT identifies precipitating events associated with the clinical course of acutely decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;74:1097-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Arroyo V, Angeli P, Moreau R, Jalan R, Clària J, Trebicka J, Fernández J, Gustot T, Caraceni P, Bernardi M; investigators from the EASL-CLIF Consortium, Grifols Chair and European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure (EF-Clif). The systemic inflammation hypothesis: Towards a new paradigm of acute decompensation and multiorgan failure in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;74:670-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 70.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ascha M, Hanouneh M, S Ascha M, Zein NN, Sands M, Lopez R, Hanouneh IA. Transjugular Intrahepatic Porto-Systemic Shunt in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease ≥15. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:534-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Salerno F, Cammà C, Enea M, Rössle M, Wong F. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:825-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Spengler EK, Hunsicker LG, Zarei S, Zimmerman MB, Voigt MD. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt does not independently increase risk of death in high model for end stage liver disease patients. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1:460-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Alessandria C, Gaia S, Marzano A, Venon WD, Fadda M, Rizzetto M. Application of the model for end-stage liver disease score for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites and renal impairment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:607-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |