Published online Jul 28, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i28.3706

Peer-review started: April 18, 2022

First decision: May 29, 2022

Revised: June 9, 2022

Accepted: June 24, 2022

Article in press: June 24, 2022

Published online: July 28, 2022

Processing time: 99 Days and 13.4 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has characteristics of family cluster infection; however, its family-based infection status, related factors, and transmission pattern in central China, a high-risk area for H. pylori infection and gastric cancer, have not been evaluated. We investigated family-based H. pylori infection in healthy households to understand its infection status, related factors, and patterns of transmission for related disease prevention.

To investigate family-based H. pylori infection status, related factors, and patterns of transmission in healthy households for related disease prevention.

Blood samples and survey questionnaires were collected from 282 families including 772 individuals. The recruited families were from 10 selected communities in the greater Zhengzhou area with different living standards, and the family members’ general data, H. pylori infection status, related factors, and transmission pattern were analyzed. H. pylori infection was confirmed primarily by serum H. pylori antibody arrays; if patients previously underwent H. pylori eradication therapy, an additional 13C-urea breath test was performed to obtain their current infection status. Serum gastrin and pepsinogens (PGs) were also analyzed.

Among the 772 individuals examined, H. pylori infection rate was 54.27%. These infected individuals were from 246 families, accounting for 87.23% of all 282 families examined, and 34.55% of these families were infected by the same strains. In 27.24% of infected families, all members were infected, and 68.66% of them were infected with type I strains. Among the 244 families that included both husband and wife, spouse co-infection rate was 34.84%, and in only 17.21% of these spouses, none were infected. The infection rate increased with duration of marriage, but annual household income, history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption, dining location, presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, and family history of gastric disease or GC did not affect infection rates; however, individuals who had a higher education level showed lower infection rates. The levels of gastrin-17, PGI, and PGII were significantly higher, and PGI/II ratio was significantly lower in H. pylori-infected groups than in H. pylori-negative groups.

In our study sample from the general public of central China, H. pylori infection rate was 54.27%, but in 87.23% of healthy households, there was at least 1 H. pylori-infected person; in 27.24% of these infected families, all members were infected. Type I H. pylori was the dominant strain in this area. Individuals with a higher education level showed significantly lower infection rates; no other variables affected infection rates.

Core Tip: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has characteristics of family cluster infection. However, few studies have investigated family-based infection status and pattern of intrafamilial transmission in the general public of central China. In our study, H. pylori infection rate was 54.27%, but in 87.23% of healthy households, there was at least 1 H. pylori-infected person; in 27.24% of these infected families, all members were infected. Type I H. pylori was the dominant strain in this area. Intrafamilial infection status and patterns of transmission represent one important source of H. pylori spread, indicating the urgent need for family-based infection control and related disease prevention.

- Citation: Yu XC, Shao QQ, Ma J, Yu M, Zhang C, Lei L, Zhou Y, Chen WC, Zhang W, Fang XH, Zhu YZ, Wu G, Wang XM, Han SY, Sun PC, Ding SZ. Family-based Helicobacter pylori infection status and transmission pattern in central China, and its clinical implications for related disease prevention. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(28): 3706-3719

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i28/3706.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i28.3706

Chronic Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is the major cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer (GC), and is also closely associated with a number of extra-gastrointestinal (GI) diseases[1-3]. H. pylori infection rate in China is about 50%, but the infection rate varies widely in different regions due to economic development, age, lifestyle habit, and sanitary conditions[4-6]. H. pylori has characteristics of family cluster infection[7]. Most H. pylori infections are acquired during childhood and adolescence, and infection will persist for decades unless proper treatment is offered.

Mounting evidence has demonstrated that transmission of H. pylori is mainly by oral-oral and fecal-oral routes, and water sources[8,9], and intra-familial spread is the major source of H. pylori trans

Type I [cytotoxin-associated protein-positive (CagA+), vacuolating cytotoxin-positive (VacA+)] H. pylori infection causes severe gastric inflammation and is prone to induce carcinogenesis[19,20]. Our previous study of 3572 patients admitted to the hospital showed that the H. pylori infection rate was 75.9% in this area of central China. The infection rate was further confirmed by investigation of 523 endoscopy-confirmed patients (76.9%), of whom 72.4% (291/402) had type I H. pylori infection and 27.5% had type II H. pylori infection. Importantly, 88.4% of GC patients were H. pylori-positive, of whom 84.2% had type I infection; only 11.6% of GC patients were H. pylori-negative[21]. At present, the genotype of family based-H. pylori infection in the healthy household is unclear, as well as its relationship with GC epidemiological markers such as gastrin-17 (G-17), pepsinogen (PG) level, and PG I/II ratio (PGR).

Henan province in central China is one of the high-risk areas for H. pylori and GC, with an H. pylori infection rate of 49.6%[22] and GC incidence of 42.52/100000[23]. The capital city, Zhengzhou, has a population of 12 million, but there has been no large-scale family-based H. pylori intrafamilial transmission survey, and the factors that affect H. pylori spread and cause disease are also unclear.

Therefore, we investigated family-based H. pylori infection status, factors related to bacteria spread, bacteria genotype, and patterns of transmission for the residents in this area, and analyzed their impact on GC epidemiological markers including G-17, PGI, PGII, and PGR. The results of this study will provide information on H. pylori infection status in the household and help to refine eradication strategies for the prevention of related diseases.

From September 2020 to April 2021, blood samples and questionnaires were collected from family members of 10 selected communities in greater Zhengzhou area; each community enrolled 20-30 families, with all members participating. The 10 communities were selected based on high, middle, and low living standards to prevent biased selection of the population; these included two high-income communities, six middle-class communities, and two communities originating from rural areas. Spe

A total of 282 families (family size ≥ 2 persons) including 772 individuals participated in the survey. Inclusion criteria were: Family members being long-term residents living in Zhengzhou area, with no age limit; all family members being willing to participate by providing blood samples and filling out the questionnaire; at least 2 people composing the family unit, but with no limitation on how many people are living in the same household; and all family members being willing to provide written informed consent. An infected family was defined as a household with various family members infected with H. pylori, ranging from only 1 person to all family members being infected, and a family could be composed of only a couple, with or without children. Exclusion criteria were: Pregnant and breastfeeding females; people with mental illness; or people who refused to fill out the questionnaire or sign the consent form.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University (No. 53, 2021). All subjects provided written informed consent; for minor subjects, written informed consent was given by their legal guardian. This study was registered in the China Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org.cn; No. ChiCTR2100052950), and the protocol is freely available from the website after registration.

Before and during enrollment, an introduction brochure or information booklet for the study was distributed to the community center staff, who were responsible for distributing and helping recruit community family members for onsite registration. A registration website was also open to community members for whole family-based registration; registration for only a single individual was declined. A questionnaire was filled out either online or onsite by each of the participating family members. Blood samples were collected from each participating member for H. pylori, gastrin, and PG analyses; if necessary, 13C-urea breath test (UBT) was subsequently performed by appointment.

Based on the purpose of this study, questionnaire included the following 17 items: Age; sex; family ethic; number of family members; professions; marriage status; socioeconomic data; dining history; living habits; lifestyle; disease history; medication history; presence of GI symptoms; H. pylori eradication history; history of gastroscopy; infection history of other family members; and treatment history (Table 1).

| Variables items, n | H. pylori positive | H. pylori negative, n | Infection rate (%) | P value | ||

| Sub total, n | Type I, n | Type II, n | ||||

| Total (772) | 419 | 328 | 91 | 353 | 54.27 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (330) | 173 | 130 | 43 | 157 | 52.42 | |

| Female (442) | 246 | 198 | 48 | 196 | 55.66 | 0.373 |

| Age (yr) (mean ± SD)1 | ||||||

| Total (45.36 ± 19.38) | 49.38 ± 16.92 | 49.59 ± 17.04 | 48.65 ± 16.47 | 40.58 ± 20.97 | 0.000a | |

| Male (44.56 ± 20.19) | 49.62 ± 18.06 | 49.21 ± 18.53 | 50.86 ± 16.50 | 38.98 ± 20.93 | ||

| Female (45.95 ± 18.74) | 49.22 ± 16.06 | 49.83 ± 15.97 | 46.67 ± 16.20 | 41.86 ± 20.92 | 0.240b | |

| Family annual income2 (10000 RMB) | ||||||

| < 10 (287) | 171 | 142 | 29 | 116 | 59.58 | |

| 10-20 (209) | 119 | 86 | 33 | 90 | 56.94 | 0.555c |

| 20-30 (84) | 47 | 36 | 11 | 37 | 55.95 | 0.552c |

| > 30 (59) | 34 | 27 | 7 | 25 | 57.63 | 0.781c |

| Unknown (47) | 28 | 20 | 8 | 19 | 59.57 | |

| Cigarette smoking2 | ||||||

| Yes (158) | 91 | 64 | 27 | 67 | 57.59 | |

| No (520) | 302 | 242 | 60 | 218 | 58.08 | 0.914 |

| Unknown (8) | 6 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 75.00 | |

| Alcohol drinking2 | ||||||

| Yes (149) | 86 | 64 | 22 | 63 | 57.72 | |

| No (511) | 297 | 233 | 64 | 214 | 58.12 | 0.930 |

| Unknown (26) | 16 | 14 | 2 | 10 | 61.54 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms2 | ||||||

| Yes (311) | 183 | 145 | 38 | 128 | 58.84 | |

| No (339) | 193 | 148 | 45 | 146 | 56.93 | 0.622 |

| Unknown (36) | 23 | 18 | 5 | 13 | 63.89 | |

| Dining location2 | ||||||

| Home (472) | 276 | 215 | 61 | 196 | 58.47 | |

| Restaurant (186) | 106 | 83 | 23 | 80 | 56.99 | 0.728 |

| Unknown (28) | 17 | 13 | 4 | 11 | 60.71 | |

| Family history of stomach disease3 | ||||||

| Yes (167) | 92 | 65 | 27 | 75 | 55.09 | |

| No (430) | 256 | 205 | 51 | 174 | 59.53 | 0.323 |

| Unknown (89) | 51 | 41 | 10 | 38 | 57.30 | |

| Family history of gastric cancer3 | ||||||

| Yes (41) | 23 | 20 | 3 | 18 | 56.10 | |

| No (576) | 335 | 260 | 75 | 241 | 58.16 | 0.796 |

| Unknown (69) | 41 | 31 | 10 | 28 | 59.42 | |

| Education level2 | ||||||

| Senior and below (286) | 180 | 142 | 38 | 106 | 62.94 | |

| University or above (376) | 199 | 155 | 44 | 177 | 52.93 | 0.010a |

| Unknown (24) | 20 | 14 | 6 | 4 | 83.33 | |

Three milliliters of fasting venous blood were collected from all subjects in the morning. Blood samples were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min, (80-2 centrifuge; Jiangsu Zhongda Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China), and samples were either analyzed on ice on the same day or stored at -80 °C for subsequent analyses. Serum anti-H. pylori antibodies [detecting CagA, VacA, UreA, UreB via H. pylori enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Blot Biotech Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China)] and G-17, PGI, PGII levels, as well as PGR (via PGI, PGII, G-17 ELISA kits; Biohit Biotechnology, Helsinki, Finland) were measured by an ELISA kit following manufacturer’s instructions as previously reported[22]. If patients had previously undergone H. pylori eradication therapy, an additional 13C-UBT was performed to obtain their current infection status (13C-UBT Diagnostic Kit; Beijing Boran Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD, whereas categorical variables are described as percentages or frequencies. The measurement data were compared by t-test, and the enumeration data were compared by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

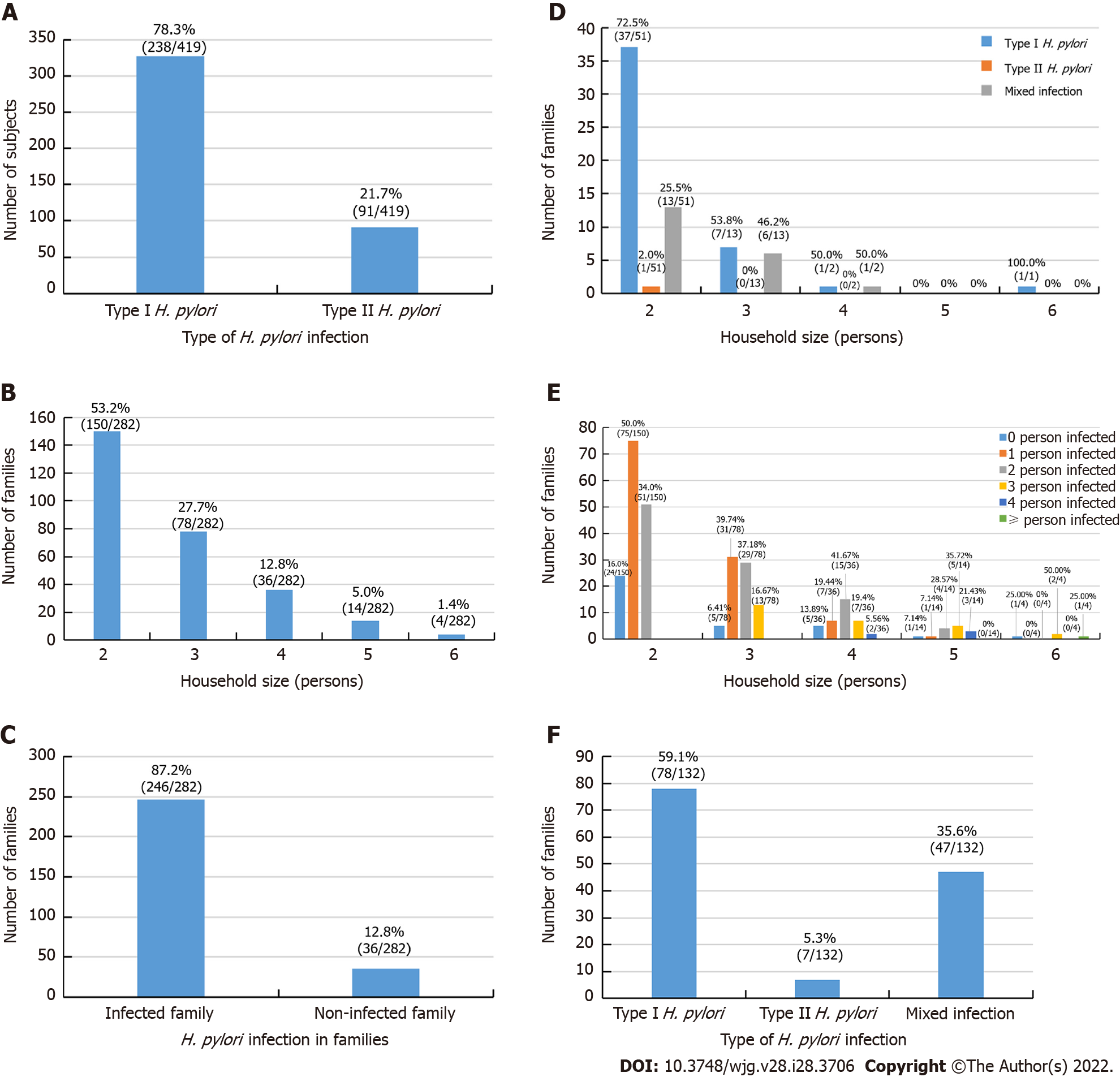

As shown in Table 1, a total of 282 families including 772 members participated in this study. Among them, 419 had H. pylori infection, giving an overall infection rate of 54.27% (419/772); among the infected individuals, 328 (42.49%, 328/772) were infected with type I strains and 91 (11.79%, 91/772) were infected with type II strains. Type I strains accounted for 78.28% (328/419) of cases, and type II strains accounted for 21.7% (91/419) of infected individuals (Figure 1A).

In total, 330 (42.75%) of the study participants were male, with an average age of 44.56 ± 20.19 years, and 442 (57.25%) were female, with an average age of 45.95 ± 18.74 years (P > 0.05). The age range of the enrolled individuals was 3 years to 90 years, with the youngest and oldest infected individuals aged 5 years and 87 years, respectively.

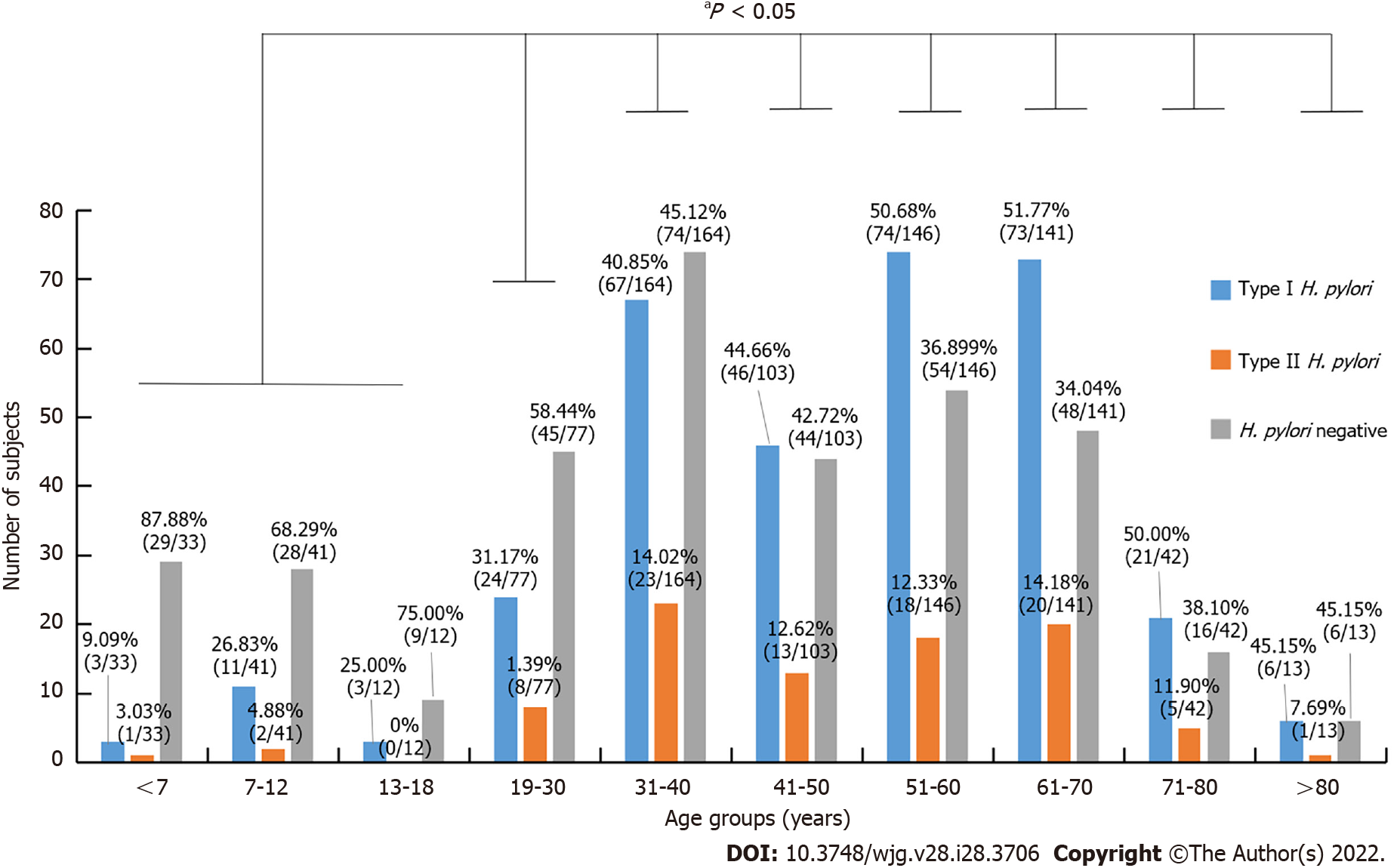

As shown in Figure 2, stratified age and H. pylori genotype infection were further analyzed, type I strains was the dominant strains for all age groups. The infection rates of individuals under the age of 18 were 23.26% (20/86), and the age groups of 51-60 and 61-70 years had the highest infection rates of 63.01% (92/146) and 65.95% (93/141), respectively. Compared with age groups under 18-years-old, the infection rate was significantly higher in groups above 18-years-old (P < 0.05), but there was no difference in infection rates among groups above 18-years-old (P > 0.05).

Among questionnaire variables (Table 1), annual household income, history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption, dining location, presence of GI symptoms, and family history of gastric disease and GC did not affect infection rates (P > 0.05), but individuals with a higher education level showed significantly lower infection rates (P < 0.05).

The average family size of the study cohort was 2.74 persons per households, and family size ranged from as few as 2 persons per family to as many as 6 per family (Figure 1B). In this survey, 2- and 3-person households accounted for 80.85% (228/282) of the families enrolled.

As shown in Figure 1C-F, H. pylori-infected individuals were distributed in 246 of the 282 families with varying numbers of members infected, ranging from only 1 person to all family members infected. The family infection rate was 87.23% with at least 1 person infected in a family unit (246/282), in 12.77% of the 282 households, no family members were infected (36/282) (Figure 1C). In 67 of the 246 infected families, all members were infected (27.24%, 67/246), among these 67 all member-infected households, 46 households were infected with the same type I strains (68.66%, 46/67), 1 household was infected with type II strains (1.49%, 1/67), and 20 households had mixed type I and II strain infection (29.85%, 20/67) (Figure 1D). The data of the stratified family member infection rate of 282 households were shown in Figure 1E. In 53.66% (132/246) of families with at least 2 members infected, 59.09% (78/132) of these families were infected with type I strains, 5.30% (7/132) were infected with type II strains, and 35.61% (47/132) were infected with mixed type I and II strains (Figure 1F).

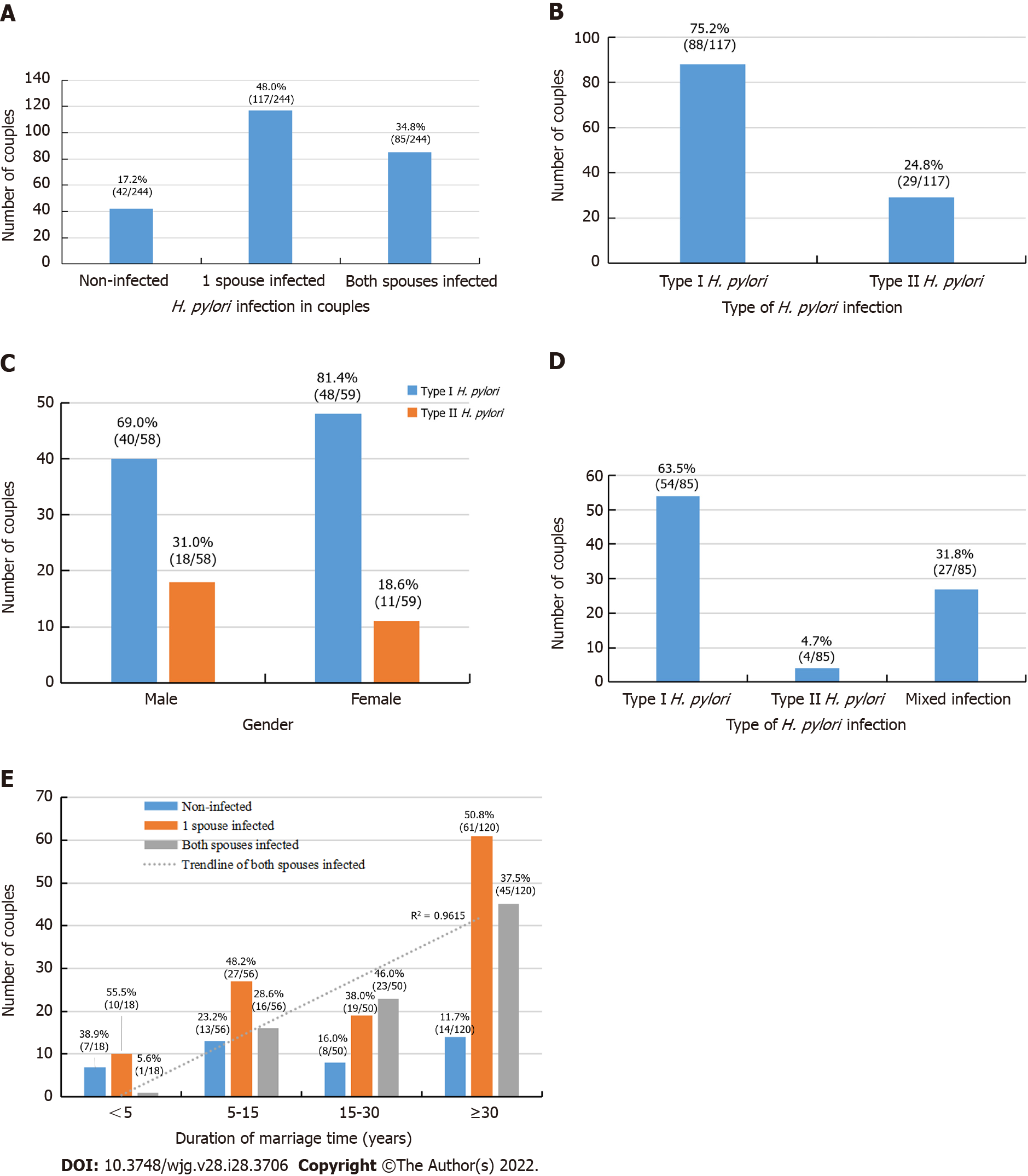

H. pylori infection status between couples is shown in Figure 3. In all, 244 of the 282 families had both spouses, and infection rate of both spouses was 34.84% (85/244); further, 17.21% (42/244) couples were not infected, and 47.95% (117/244) had only a single spouse infection (Figure 3A). Among 117 families with infection of only 1 spouse, 75.21% (88/117) were infected with type I strains and 24.79% (29/117) were infected with type II strains (Figure 3B). Of these spouses, the husband was infected in 49.57% (58/117) of cases and the wife was infected in 50.53% (59/117) of cases (P > 0.05), they were further stratified into type I and type II strains infections (Figure 3C). Furthermore, among the 85 families with both husband and wife co-infected with H. pylori, 68.24% (58/85) were infected with the same type of strain, of whom 63.53% (54/85) were infected with type I strains, 4.71% (4/85) were infected with type II strains, and 31.76% (27/85) had mixed type I and type II infection (Figure 3D). Significantly more couples were infected with the same type of strain than with mixed strains (P < 0.05). In addition, with the increase in marriage duration, infection rate of both husband and wife was significantly increased (r = 0.98, P < 0.05; Figure 3E).

In 51 families with both parents and children younger than 18 years of age, as shown in Table 2, the infection rate of children was 23.08% (6/26) when both parents were H. pylori-infected; however, when both parents were not infected, the infection rate of children was 18.18% (2/11) (P > 0.05). When only mother was infected, the infection rate of children was 45.45% (5/11); no child was infected (0/9) when only father was infected (P > 0.05).

| Parental infection (Household numbers) | Children infection (57) | Infection rate (%) | P value | |

| H. pylori+ (n) | H. pylori- (n) | |||

| Neither parent infected (11) | 2 | 9 | 18.18 | |

| Both parent infected (21) | 6 | 20 | 23.08 | 0.109a |

| Only father infected (9) | 0 | 9 | 0 | |

| Only mother infected (10) | 5 | 6 | 45.45 | |

| Total (51) | 13 | 44 | 22.81 | |

Table 3 shows infection status of the 51 families comprising both parents and children, for a total of 190 individuals. Among these family members, the infection rates were as follows: Father, 62.75% (32/51); mother, 62.75% (32/51); grandfather, 50.00% (2/4); grandmother, 66.67% (8/12); maternal grandfather, 25.00% (1/4); maternal grandmother, 37.50% (3/8); and other relatives, 66.67% (2/3).

| Family members (N) | H. pylori positive | H. pylori negative, n | Infection rate (%) | ||

| Sub total, n | Type I H. pylori, n | Type II H. pylori, n | |||

| Total (190) | 93 | 66 | 27 | 97 | 48.95 |

| Father (51) | 32 | 23 | 9 | 19 | 62.75 |

| Mother (51) | 32 | 22 | 10 | 19 | 62.75 |

| Grandfather (4) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 50.00 |

| Grandmother (12) | 8 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 66.67 |

| Maternal grandfather (4) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 25.00 |

| Maternal grandmother (8) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 37.50 |

| Other relatives (3) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 66.67 |

| Child (57) | 13 | 10 | 3 | 45 | 22.81 |

To determine the impact of H. pylori infection on common GC epidemiological markers (e.g., G-17, PGI, PGII, and PGR) in healthy households, we assayed their levels during H. pylori infection. As shown in Table 4, compared to H. pylori-negative groups, PGI levels were significantly higher and PGR was significantly lower in H. pylori type I infections compared with H. pylori-negative groups (P < 0.05). However, there were no differences in G-17, PGII level, and PGR between type II H. pylori infection and H. pylori-negative groups (P > 0.05). The levels of G-17, PGI, and PGII were significantly higher, and PGR was significantly lower in H. pylori-infected groups than in H. pylori-negative groups (P < 0.05).

| H. pylori+ | Type I H. pylori | Type II H. pylori | H. pylori- | |

| G-17 (pmol/L) | 8.95 ± 14.53 | 9.87 ± 15.60 | 5.62 ± 9.10c | 4.90 ± 9.21a,d |

| PGI (μg/L) | 117.90 ± 55.99 | 123.12 ± 57.11 | 99.10 ± 47.45 | 91.13 ± 38.29a,b,d |

| PGII (μg/L) | 12.66 ± 10.41 | 13.83 ± 11.07 | 8.43 ± 5.91c | 7.39 ± 6.82a,d |

| PGR | 12.16 ± 6.39 | 11.64 ± 6.40 | 14.05 ± 6.04c | 15.58 ± 7.97a,d |

H. pylori infection rates vary greatly among different countries and regions[24]. Although numerous studies have demonstrated that intrafamilial transmission is one of the most important sources of H. pylori spread[2,18,24], there are few studies on the characteristics and pattern of family-based H. pylori infection for disease prevention and control[9,25,26]. Therefore, focusing on family-based H. pylori infection control and management would be a novel approach to reduce the related diseases and GC burden in a society.

In this work, we analyzed H. pylori infection status in a total of 772 individuals from 282 families in the Zhengzhou area. The results showed that despite an overall infection rate of only 54.27%, in as high as 87.23% of the surveyed families (246/282), there was at least 1 person infected, and in 27.07% (67/246) of these infected families, all family members were infected; further, 34.55% (85/246) of these families were infected with the same type of strain. Therefore, this study provides new evidence showing the importance of family-based H. pylori infection control, which has substantive public health implications, and suggests that intrafamilial infection is a major source of H. pylori transmission. Thus, preventing intrafamilial spread is critical to eliminate the source of infection in order to prevent the related diseases.

Over the past several decades, the social and family structure in China has changed dramatically. The latest national statistics[27] (2020) revealed that the nation has a population of 1.41 billion and 492 million families with an average family size of 2.62 persons/family, which is much smaller than it was in 1990, when China had 1.13 billion citizens and 278.6 million families, with an average family size of 4.05 persons/family[27]. Due to the previous nationwide “one-children-per-family policy” (between 1982 and 2016), most families in China only have 1 child and two generations. As these children do not have siblings, transmission among siblings within a family unit did not appear to be the major route of transmission in the current analysis. H. pylori spread from parent or grandparent to children is probably more important for bacteria transmission. Although the current results provide a snapshot of H. pylori infection status in the general public, a nationwide large-scale investigation is needed to explore the nationwide infection status and develop policies for related disease prevention.

In single factor analysis, we noted that the highly infected age groups were between 31 years and 70 years, and infection rates increased along with age and duration of marriage. Annual household income, history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption, dining location, and family history of gastric disease or GC were not different between the infected and non-infected groups, but individuals with a higher education level showed a lower infection rate. A 2020 all-ages population-based cross-sectional study[28] in Wuwei county in northwestern China showed that the prevalence of H. pylori infection was closely associated with socioeconomic conditions, sanitary situations, dietary habits of the participants in the city. Boarding, eating at school, and drinking untreated water were main factors explaining the rising infection rate in junior-senior high school students. The results indicated that close contact is associated with increased infection risk. In addition, differences in geographic location, study population, lifestyle habit, and sanitary conditions are important factors that greatly contribute to H. pylori infection[22,29,30].

Similar results were obtained from other regions, such as one community-based study[31] in Vietnam in 2017 on familial clustering in a multiple-generation population. The study showed that high monthly income, not regularly being fed chewed food, and being breastfed were protective factors against H. pylori infection. Risk factors for H. pylori infection in children were not regularly handwashing after defecation, H. pylori-infected mother and grandfather, father’s occupation, mother’s education, and household size. Other factors such as number of siblings, infected fathers, regularly sharing a bed, group living, and antibiotic use were not found to be significant risk factors for infection.

H. pylori-infected family members are a possible source of continued transmission, which is an important health threat for uninfected family members[7,32,33]. A 2003 study[9] in the Stockholm area of Sweden using bacterial isolates for family-based DNA fingerprinting technique demonstrated a high proportion of shared strains among siblings, and between spouses, but also showed different strains in a portion of subjects (8%). Similar results were also reported by a 2009 study in Bangladesh[26]. In the current analysis, we found that among the 67 all member-infected households (Figure 1F), 68.66% (46/67) were infected with H. pylori type I strains, 1.49% (1/67) were infected with type II strains, and 29.85% (20/67) had mixed type I and II strain infection. These data support the notion that intrafamilial transmission is the primary transmission route, but exogenous infection outside the family can occur, indicating that there may be multiple sources of transmission. In 244 couples comprising both husband and wife, 34.84% (85/244) of them were co-infected, and 68.24% (58/85) of households were infected with the same strain. With an increase of marriage duration, the infection rate of both husband and wife was significantly increased, suggesting that there was also cross-infection between husband and wife.

One unexpected result was that when both parents were infected, the infection rate of children was 23.08% (6/21), whereas when both parents were not infected, the infection rate of children was 18.18% (2/11), and the difference did not reach statistical significance. This result was slightly different from our previous concept that parental H. pylori infection is an independent factor for infection in young children, and that mothers play an important role in H. pylori transmission to their descendent[13-15,26]. However, the current results likely reflect the current infection status in this region, as the gradually improved living standard, sanitary condition, use of tap water, and avoiding chewing food to feed children over the past several decades in China’s urban family have resulted in a reduced infection rate. This is in line with the fact that the overall H. pylori infection rate is declining in most of China’s urban areas[3,22]. Another possibility is that the current cohort had relatively small numbers of children and adolescents, which may not have generated enough power for statistical significance. In addition, we were unable to perform bacterial DNA fingerprinting to confirm if the strains were identical, so the genotype that precise bacterial strains transmit within a family unit has yet to be determined. Future large-scale investigations are needed to confirm the current conclusion.

Type I H. pylori strain accounted for 78.28% of the infected population in this survey, similar to the results of our previous study in patients admitted to the hospital, which showed that type I H. pylori infection accounted for 72.4% (291/402) of the infected patients, and type II was 27.6%[21]. When compared to H. pylori-negative groups, G-17, PGI, and PGII levels were higher in H. pylori-infected groups. G-17, PGI, and PGII levels were significantly higher and PGR was significantly lower in the type I H. pylori-infected groups than in H. pylori-negative groups. The levels of G-17 and PG II were significantly higher, and PGR was significantly lower in type I H. pylori-infected groups than in type II-infected groups. These results are in line with our previous endoscopy results from inpatients, and indicate that both type I and type II H. pylori strains increase G-17 Level, whereas only type I H. pylori infection affects PGI and PGII levels and the PGR in this geographic area[21].

Type I infection and reduced PGR are risk factors for gastric mucosal precancerous lesions and GC[19,21]. Therefore, these results have important clinical implications, as the abnormal expression of gastric markers was noted in a portion of individuals in healthy households infected with H. pylori before they sought medical examinations. It was unclear if this group of individuals had gastric mucosal precancerous lesions; thus, further examinations by endoscopy may be required for confirmation. The results of this study also provide another line of support showing that family-based H. pylori infection control and management would be an important strategy for infection control and related disease prevention[3,18,34,35].

Although this pilot work provides novel information regarding family-based H. pylori infection status, it had some limitations. First, the investigation was performed with a relatively small number of families, and in some groups, especially children and adolescents, the number of samples was not large enough to reach statistical significance; thus, future large-scale, multiple region sampling would provide more convincing data. Second, this was a cross-sectional study without data from endoscopy to confirm H. pylori infection-related disease status and pathological changes in gastric mucosa; therefore, some in-depth information was missing, and the work was performed in a Chinese setting, which may not be suitable to other areas. Third, type I and II H. pylori genotype concordance through antibody array analysis only provided a very general evaluation. As we did not obtain bacteria strain culture and DNA fingerprinting data, H. pylori intrafamilial transmission was unable to be evaluated precisely to assess the heterogeneity of H. pylori strains within families. Thus, future studies are needed to evaluate the H. pylori DNA fingerprinting pattern for more precise evaluation. Even with these limitations, this study provides novel points and information on family-based H. pylori infection characteristics, which merit further large-scale exploration.

The current results provide snapshots of family-based H. pylori infection status in central China. The high infection rate and coincidence of people infected with H. pylori within a family unit indicate the status and pattern of intrafamilial transmission, which provide a novel option for family-based H. pylori infection control and related disease prevention. The concept is applicable not only to Chinese residents but also to other communities with high infection rates.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has characteristics of family cluster infection; however, its family-based infection status, related factors, and transmission pattern in central China have not been evaluated.

We evaluated family-based H. pylori infection status, related factors, and interfamilial transmission pattern in healthy households in central China, a high-risk area for H. pylori and gastric cancer (GC).

To investigate family-based H. pylori infection and identify a better approach for H. pylori infection control and related disease prevention.

H. pylori infection was confirmed primarily by serum antibody arrays in 282 enrolled families, including a total of 772 family members. If patients previously underwent H. pylori eradication therapy, an additional 13C-urea breath test was performed to obtain their current infection status. Serum levels of gastrin and pepsinogens (PGs) were also analyzed.

In our study sample from the general public of central China, H. pylori infection rate was 54.27%. In 87.23% of healthy households, there was at least 1 H. pylori-infected person, and in 27.24% of these infected families, all members were infected. Type I H. pylori was the dominant strain in this geographic area. Among many variables, only individuals with a higher education level showed lower infection rates. H. pylori infection was also correlated with abnormal gastrin-17, PGI, and PGII levels and PGI/PGII ratio.

H. pylori infection in healthy households is very common in central China, and poses an important health threat to uninfected family members. The intrafamilial infection status and patterns of transmission represent one important source of H. pylori spread, and indicate the urgent need for family-based infection control and related disease prevention.

The results of this study provide new information on family-based H. pylori infection status in central China, and support the novel concept of family-based H. pylori infection control and management. This notion is also likely to benefit other H. pylori and GC prevalent areas.

The authors are grateful to the staff of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University, for their valuable assistance in this work.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kotelevets SM, Russia; Tilahun M, Ethiopia S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2220] [Cited by in RCA: 1983] [Article Influence: 247.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Fallone CA, Chiba N, van Zanten SV, Fischbach L, Gisbert JP, Hunt RH, Jones NL, Render C, Leontiadis GI, Moayyedi P, Marshall JK. The Toronto Consensus for the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Adults. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:51-69.e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 695] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 70.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ding SZ, Du YQ, Lu H, Wang WH, Cheng H, Chen SY, Chen MH, Chen WC, Chen Y, Fang JY, Gao HJ, Guo MZ, Han Y, Hou XH, Hu FL, Jiang B, Jiang HX, Lan CH, Li JN, Li Y, Li YQ, Liu J, Li YM, Lyu B, Lu YY, Miao YL, Nie YZ, Qian JM, Sheng JQ, Tang CW, Wang F, Wang HH, Wang JB, Wang JT, Wang JP, Wang XH, Wu KC, Xia XZ, Xie WF, Xie Y, Xu JM, Yang CQ, Yang GB, Yuan Y, Zeng ZR, Zhang BY, Zhang GY, Zhang GX, Zhang JZ, Zhang ZY, Zheng PY, Zhu Y, Zuo XL, Zhou LY, Lyu NH, Yang YS, Li ZS; National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (Shanghai), Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention & Treatment Alliance of China (GECA), Helicobacter pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, and Chinese Alliance for Helicobacter pylori Study. Chinese Consensus Report on Family-Based Helicobacter pylori Infection Control and Management (2021 Edition). Gut. 2022;71:238-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu WZ, Xie Y, Lu H, Cheng H, Zeng ZR, Zhou LY, Chen Y, Wang JB, Du YQ, Lu NH; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Study Group on Helicobacter pylori and Peptic Ulcer. Fifth Chinese National Consensus Report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 47.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P; faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1322] [Cited by in RCA: 1183] [Article Influence: 118.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brown LM, Thomas TL, Ma JL, Chang YS, You WC, Liu WD, Zhang L, Pee D, Gail MH. Helicobacter pylori infection in rural China: demographic, lifestyle and environmental factors. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:638-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Drumm B, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, Sherman PM. Intrafamilial clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:359-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kato M, Ota H, Okuda M, Kikuchi S, Satoh K, Shimoyama T, Suzuki H, Handa O, Furuta T, Mabe K, Murakami K, Sugiyama T, Uemura N, Takahashi S. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: 2016 Revised Edition. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kivi M, Tindberg Y, Sörberg M, Casswall TH, Befrits R, Hellström PM, Bengtsson C, Engstrand L, Granström M. Concordance of Helicobacter pylori strains within families. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5604-5608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Georgopoulos SD, Mentis AF, Spiliadis CA, Tzouvelekis LS, Tzelepi E, Moshopoulos A, Skandalis N. Helicobacter pylori infection in spouses of patients with duodenal ulcers and comparison of ribosomal RNA gene patterns. Gut. 1996;39:634-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rothenbacher D, Winkler M, Gonser T, Adler G, Brenner H. Role of infected parents in transmission of helicobacter pylori to their children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:674-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Perry S, de la Luz Sanchez M, Yang S, Haggerty TD, Hurst P, Perez-Perez G, Parsonnet J. Gastroenteritis and transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in households. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1701-1708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Silva LD, Santos A, Bocewicz AC, Queiroz Rd Rde M, Bethony J, Gazzinelli A, Corrêa-Oliveira R, Queiroz DM. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in families of preschool-aged children from Minas Gerais, Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:987-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang YJ, Sheu BS, Lee SC, Yang HB, Wu JJ. Children of Helicobacter pylori-infected dyspeptic mothers are predisposed to H. pylori acquisition with subsequent iron deficiency and growth retardation. Helicobacter. 2005;10:249-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Konno M, Yokota S, Suga T, Takahashi M, Sato K, Fujii N. Predominance of mother-to-child transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection detected by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting analysis in Japanese families. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:999-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nguyen VB, Nguyen GK, Phung DC, Okrainec K, Raymond J, Dupond C, Kremp O, Kalach N, Vidal-Trecan G. Intra-familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in children of households with multiple generations in Vietnam. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:459-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen XX, Ou BY, Shang SQ, Wu XY, Zhang XP, Chen LQ, Qu YP. The correlation between family aggregation and eradication therapy in children with Helicobacter pylori infection. Zhongguo Shiyong Erke. 2003;18:475-477. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Sari YS, Can D, Tunali V, Sahin O, Koc O, Bender O. H pylori: Treatment for the patient only or the whole family? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1244-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Matos JI, de Sousa HA, Marcos-Pinto R, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Helicobacter pylori CagA and VacA genotypes and gastric phenotype: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1431-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ding SZ, Goldberg JB, Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori infection, oncogenic pathways and epigenetic mechanisms in gastric carcinogenesis. Future Oncol. 2010;6:851-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yuan L, Zhao JB, Zhou YL, Qi YB, Guo QY, Zhang HH, Khan MN, Lan L, Jia CH, Zhang YR, Ding SZ. Type I and type II Helicobacter pylori infection status and their impact on gastrin and pepsinogen level in a gastric cancer prevalent area. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:3673-3685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li M, Sun Y, Yang J, de Martel C, Charvat H, Clifford GM, Vaccarella S, Wang L. Time trends and other sources of variation in Helicobacter pylori infection in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2020;25:e12729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu S, Chen Q, Quan P, Zhang M, Zhang S, Guo L, Sun X, Wang C. Cancer incidence and mortality in Henan province, 2012. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016;28:275-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, Miller WH, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Shokri-Shirvani J, Derakhshan MH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:868-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 494] [Article Influence: 70.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Nahar S, Kibria KM, Hossain ME, Sultana J, Sarker SA, Engstrand L, Bardhan PK, Rahman M, Endtz HP. Evidence of intra-familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori by PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting in Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:767-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kivi M, Johansson AL, Reilly M, Tindberg Y. Helicobacter pylori status in family members as risk factors for infection in children. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:645-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | National Bureau of Statistics of China. China statistical Yearbook 2020. China Statistical Press, 2020. |

| 28. | Wang X, Shu X, Li Q, Li Y, Chen Z, Wang Y, Pu K, Zheng Y, Ye Y, Liu M, Ma L, Zhang Z, Wu Z, Zhang F, Guo Q, Ji R, Zhou Y. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Wuwei, a high-risk area for gastric cancer in northwest China: An all-ages population-based cross-sectional study. Helicobacter. 2021;26:e12810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ding Z, Zhao S, Gong S, Li Z, Mao M, Xu X, Zhou L. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic Chinese children: a prospective, cross-sectional, population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:1019-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ito LS, Oba-Shinjo SM, Shinjo SK, Uno M, Marie SK, Hamajima N. Community-based familial study of Helicobacter pylori infection among healthy Japanese Brazilians. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:208-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nguyen TV, Phan TT, Nguyen VB, Hoang TT, Le TL, Nguyen TT, Vu SN. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Muong children in Vietnam. Ann Clin Lab Res. 2017;5:1-9. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Garg PK, Perry S, Sanchez L, Parsonnet J. Concordance of Helicobacter pylori infection among children in extended-family homes. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:450-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Osaki T, Konno M, Yonezawa H, Hojo F, Zaman C, Takahashi M, Fujiwara S, Kamiya S. Analysis of intra-familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese families. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhao JB, Yuan L, Yu XC, Shao QQ, Ma J, Yu M, Wu Y, Qi YB, Hu RB, Wei PR, Jia BL, Zhang LZ, Zhang YR, Ding SZ. Whole family-based Helicobacter pylori eradication is a superior strategy to single-infected patient treatment approach: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2021;26:e12793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhou G. Helicobacter pylori Recurrence after Eradication Therapy in Jiangjin District, Chongqing, China. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:7510872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |