Published online Jul 28, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i28.3682

Peer-review started: January 9, 2022

First decision: March 8, 2022

Revised: April 2, 2022

Accepted: June 21, 2022

Article in press: June 21, 2022

Published online: July 28, 2022

Processing time: 198 Days and 10.7 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infects about 50% of the world population and is the major cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer. Chronic H. pylori infection induces gastric mucosal precancerous lesions mostly in adulthood, and it is debatable whether these pathological conditions can occur in childhood and adolescents as well. Since this is a critical issue to determine if intervention should be offered for this population group, we investigated the gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in pediatric patients in an area in central China with a high prevalence of H. pylori and gastric cancer.

To investigate the relationship of H. pylori infection and gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in children and adolescents in central China.

We screened 4258 ward-admitted children and adolescent patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms, and finally enrolled 1015 pediatric patients with H. pylori infection and endoscopic and histological data. H. pylori infection status was determined by rapid urease test and histopathological examination. Both clinical and pathological data were collected and analyzed retrospectively. Occurrence of gastric mucosal precancerous lesions, inflammatory activity and degree of inflammatory cell infiltration between H. pylori-positive and -negative groups were compared.

Among the 1015 eligible children and adolescents, the overall H. pylori infection rate was 84.14% (854/1015). The infection rate increased with age. The incidence of gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in H. pylori-infected children was 4.33% (37/854), which included atrophic gastritis (17 cases), intestinal metaplasia (11 cases) and dysplasia (9 cases). In H. pylori-negative patients, only 1 atrophic gastritis case [0.62%, (1/161)] was found (P < 0.05). Active inflammation in H. pylori-infected patients was significantly higher than that in non-infected patients, and the H. pylori-infected group showed more severe lymphocyte and neutrophil granulocyte infiltration (P < 0.001). In addition, endoscopy revealed that the most common findings in H. pylori-positive patients were antral nodularity, but in H. pylori-negative patients only superficial gastritis was observed.

In children and adolescents, gastric mucosal precancerous lesions occurred in 4.33% of H. pylori-infected patients in central China. These cases included atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia. The data revealed an obvious critical issue requiring future investigation and intervention for this population group.

Core Tip: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection induces gastric mucosal precancerous lesions mostly in adulthood. Whether these lesions can also occur in children and adolescents remains controversial. Our study showed that in a region in central China with a high prevalence of H. pylori and gastric cancer, the incidence of gastric mucosal precancerous lesions was 4.33% among H. pylori-infected children and adolescents, which is significantly higher than the non-infected pediatric patients. The precancerous lesions included atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia. These data provide an alarming alert and call for further investigation and intervention for this population group.

- Citation: Yu M, Ma J, Song XX, Shao QQ, Yu XC, Khan MN, Qi YB, Hu RB, Wei PR, Xiao W, Jia BL, Cheng YB, Kong LF, Chen CL, Ding SZ. Gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in Helicobacter pylori-infected pediatric patients in central China: A single-center, retrospective investigation. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(28): 3682-3694

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i28/3682.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i28.3682

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has infected about 50% of the Chinese population and is responsible for 90% of non-cardia gastric cancer incidences. It is reported that one-third of asymptomatic or healthy children have serologically-confirmed H. pylori infection worldwide[1-3]. Although most H. pylori-infected children do not have obvious clinical symptoms, studies have shown that children with gastrointestinal symptoms have a higher rate of H. pylori infection, and the infection rates are affected by socioeconomic status, living habit, sanitary conditions, geographic region, etc.[4,5]. Despite the overall infection rate has slowly declined in China, the infection rate in rural areas is still much higher over that of city residents[6,7].

A recent meta-analysis in China in 2022 has indicated that H. pylori prevalence in children and adolescents is 28%[7]. Infection by H. pylori is closely associated with gastric mucosal inflammation and extra-gastrointestinal diseases[8-10]. A small portion of infected patients will follow Correa’s cascade and develop severe gastric mucosal lesions, such as atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), and gastric cancer[11]. H. pylori CagA has been shown to be associated with gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in several epidemiological studies[5,12].

One 2006 review summarized the prevalence of gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in children and adolescents, ranging from 0% to 72% in H. pylori-infected patients[13]. Prevalence of gastric atrophy in different populations may also vary depending on different geographic/genetic origins or environmental factors in the pediatric population. For example, one Tunisian study in 2009 found that atrophic gastritis accounted for 9.3% (32/354) of enrolled children; of the 32 children with atrophic gastritis, 30 were infected with H. pylori[14]. In 2014, a Mexican study of 82 children with chronic gastritis found that 8.5% (7/82) children had antral atrophy and 6.1% (5/82) had IM; among the 7 children with atrophy, 6 had H. pylori infection[15]. Other studies carried out in different countries reported gastric atrophy was present in 4.4% to 10.7% of H. pylori-positive children[16,17]. However, large-scale investigation is lacking in this area.

H. pylori has the characteristics of family cluster infection and is transmissible among family members, including spouses and siblings[8,9,18]. The infected parents, especially mothers, play a major role in its transmission[19-21]. Most H. pylori infection is acquired during childhood and adolescents, and the infection will persist for decades unless proper treatment is offered. Because H. pylori infection usually does not cause or only causes mild gastric mucosal lesions in children and adolescents[22-24], the consequences were thought not to be as important as they were in adulthood. Hence, very few studies have focused on the relationships between H. pylori infection and gastric mucosa precancerous lesions in children and adolescents. Recent reports have begun to show that gastric mucosal atrophy and IM are also found in children and even in very young children, as mentioned above[13-15].

In this work, we retrospectively investigated a cohort of H. pylori-infected symptomatic pediatric inpatients on gastric mucosal inflammation status, incidence and pattern of gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in a major hospital in central China, which is an area with a high prevalence of H. pylori and gastric cancer (H. pylori infection rate is 49.6%[6], and gastric cancer incidence is 42.52/100000[25]). Studies in this area will be helpful to understand the pattern and prevalence of gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in pediatric patients and provide evidence for future H. pylori eradication recommendation and related disease prevention.

From August 1, 2018 to July 31, 2021, 4258 pediatric patients with an age less than 18-years-old who had upper gastrointestinal symptoms were admitted to the Department of Pediatrics, People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University; among them, 1852 underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy examination due to disease complaints, such as abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, hiccups, heartburn, etc. Patients who had taken biopsy specimens from the gastric mucosa for histopathological examination and rapid urease test were enrolled into the study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Use of antibiotics, bismuth salts, proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor blockers, immunosuppressants and steroids over the past 1 mo; (2) History of gastrointestinal surgery; (3) Active upper gastrointestinal bleeding; and (4) Idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease.

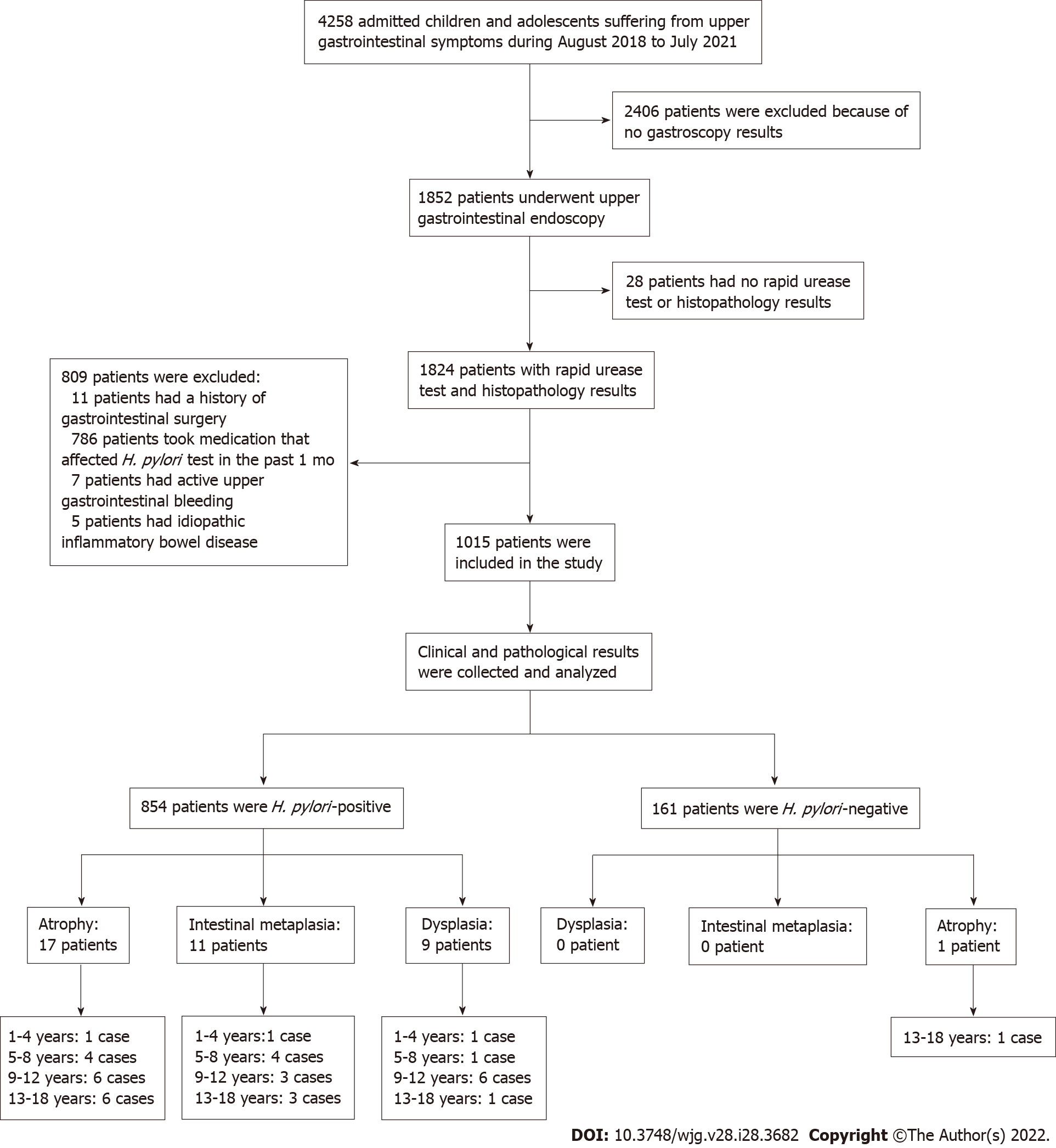

The study finally enrolled 1015 eligible children and adolescents. Patient information was collected only for the purpose of disease analysis and were kept confidential. As this is a retrospective study, no informed consent was required. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University (2019-KY-No. 10). The flow chart of study design and patients’ enrollment is shown in Figure 1. Patients were classified into four groups according to age: (1) 1-4 years; (2) 5-8 years; (3) 9-12 years; and (4) 13-18 years.

At least two biopsy specimens were collected from the antrum or angulus during endoscopic examination. One biopsy sample was used for immediate rapid urease test. The other was oriented, fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin blocks. After samples were sectioned, hematoxylin and eosin staining was applied for histological analysis. H. pylori infection was detected by immunohistochemical staining. Due to technique limitations, all patients were not given 13C-urea breath test, serological H. pylori antibody test or stool antigen test to determine H. pylori infection status at the time of their tests. Therefore, a patient was considered H. pylori-infected if either histological staining or rapid urease test was positive or if both were positive. Conversely, a patient was considered to be H. pylori-uninfected if either histological staining or rapid urease test was negative or if both were negative.

Histological variables (the activity of inflammation, lymphocyte and neutrophil granulocyte infiltration, glandular atrophy, IM and hyperplasia) were analyzed according to visual analog scale of the updated Sydney system[26]. Gastric mucosa changes were classified into absent, mild, moderate and severe levels according to the histological situation of each sample. Severity of lesions was determined by the most severe lesion in each patient. Atrophy of gastric mucosa was indicated by the destruction and reduction in gastric glands of the stomach. IM is a condition in which cells that create the lining of the stomach are changed or replaced by intestinal cells. In many cases, when gastric atrophy and IM coexist, they were allocated into either the atrophy or IM category based on the major pathological presentations of the specific patients. Dysplasia refers to a proliferative lesion, abnormal hyperplasia of the gastric gland basement membrane epithelium and abnormal changes in morphology and structure. These specimens were evaluated by two pathologists in a blinded fashion.

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables were described as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range), while categorical variables were described as percentages or frequencies. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare pathological changes of gastric mucosa, including activity of inflammation, presence of precancerous lesions and endoscopic pattern of gastric mucosa between patients with H. pylori infection and those without H. pylori infection. Grade data were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test, including degrees of inflammatory cell infiltration. A P value less than 0.05 (derived from two-tailed tests) was considered statistically significant.

A total of 1852 selected patients were further examined from a pool of 4258 pediatric ward patients (Figure 1). Then, 809 patients were excluded due to surgery, medication, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease or bleeding, and 28 more patients were excluded because of no rapid urease test or histopathological test. The remaining 1015 eligible patients were enrolled and analyzed. Patient demographic data were summarized in Table 1. Among the 1015 enrolled patients, 604 were males and 411 were females, with median age of 11-years-old, and 854 patients were infected by H. pylori, while 161 patients were not infected. The mean age of H. pylori-infected patients was significantly older than those of non-infected subjects (11 years vs 9 years, P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in sex distribution between the H pylori-infected and non-infected groups.

| Variables | Total | H. pylori+ | H. pylori- | P value |

| Patients, n | 1015 | 854 | 161 | |

| Age in year, median (IQR) | 11 (9-13) | 11 (9-13) | 9 (6-12) | < 0.001a |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 411 (40.49) | 346 (40.52) | 65 (40.37) | |

| Male | 604 (59.51) | 508 (59.48) | 96 (59.63) | 0.973 |

| Endoscopic pattern, n (%) | ||||

| Esophagitis | 28 (2.76) | 23 (2.69) | 5 (3.11) | 0.975 |

| Superficial gastritis | 331 (32.61) | 255 (29.86) | 76 (47.20) | < 0.001b |

| Superficial gastritis with erosion | 236 (23.25) | 200 (23.42) | 36 (22.36) | 0.77 |

| Superficial gastritis with bile reflux | 295 (29.06) | 251 (29.39) | 44 (27.33) | 0.597 |

| Antral nodularity | 135 (13.30) | 131 (15.34) | 4 (2.48) | < 0.001b |

| Peptic ulcer | 90 (8.87) | 80 (9.37) | 10 (6.21) | 0.196 |

| Atrophic gastritis | 18 (1.77) | 17 (1.99) | 1 (0.62) | 0.378 |

| Clinical diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Esophagitis | 28 (2.76) | 23 (2.69) | 5 (3.11) | 0.975 |

| Non atrophic gastritis | 997 (98.23) | 837 (98.01) | 160 (99.38) | 0.378 |

| Atrophic gastritis | 18 (1.77) | 17 (1.99) | 1 (0.62) | 0.378 |

| Gastric ulcer | 18 (1.77) | 16 (1.87) | 2 (1.24) | 0.817 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 72 (7.09) | 64 (7.49) | 8 (4.97) | 0.252 |

The clinical characteristics of patients are also presented in Table 1. For endoscopic manifestations, superficial gastritis was observed in 255 (29.86%) cases among the H. pylori-positive patients and 76 (47.20%) cases among the H. pylori-negative patients (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the proportion of superficial gastritis with erosion, superficial gastritis with bile reflux and esophagitis regardless of the status of H. pylori infection (P > 0.05). Antral nodularity was observed in 131 (15.34%) H. pylori-positive patients and 4 (2.48%) H. pylori-negative patients (P < 0.05). In both H. pylori-infected and non-infected patients, most patients were clinically diagnosed with non-atrophic gastritis, and only a small percentage of patients developed atrophic gastritis or peptic ulcers.

In the 1-4 years, 5-8 years, 9-12 years and 13-18 years age groups (Table 2), the H. pylori infection rates were 40.74%, 78.39%, 88.05% and 89.60%, respectively. The trend of infection rate increasing as age increased was noted. Patient infection rates of the 5-8 years, 9-12 years and 13-18 years age groups were significantly higher than that of the 1-4 years age group. Infection rates of the 9-12 years and 13-18 years age groups were also significantly higher than that of the 5-8 years age group, but the infection rates had no significant difference between the 9-12 and 13-18 years age groups.

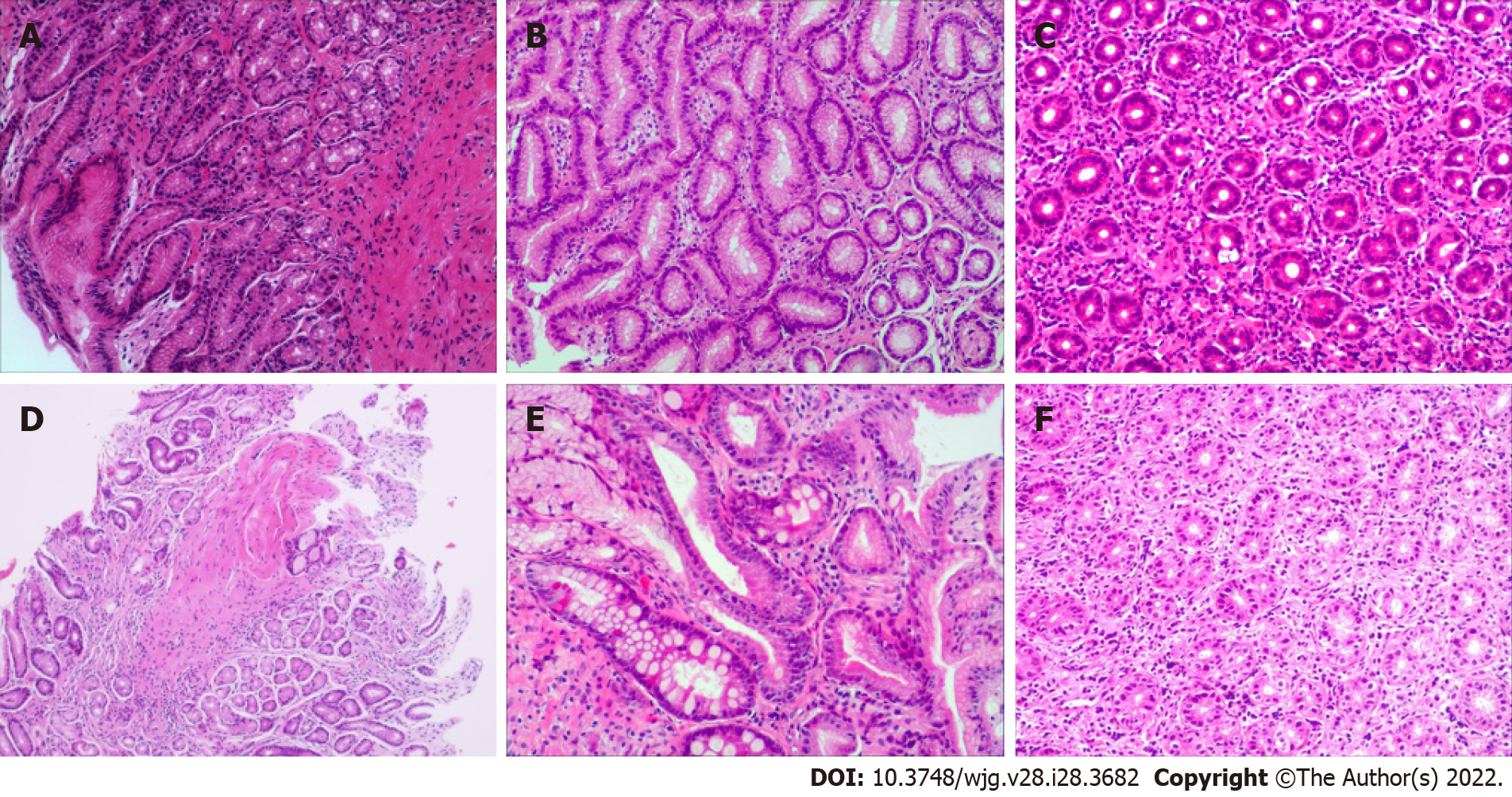

Patient gastric mucosal precancerous lesions are shown in Table 3. Among the 854 H. pylori-infected patients, 4.33% (37/854) had gastric mucosa precancerous lesions; among which, 17 patients had atrophy, 11 patients had IM, and 9 patients had dysplasia. Only 1 of the 161 H. pylori-uninfected patients (0.62%) had atrophic gastritis. The incidence of precancerous lesions of gastric mucosa in H. pylori-infected patients was significantly more than those uninfected patients (χ2= 5.178, P = 0.023). Among the H. pylori-positive patients, there were gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in each age group, whereas among the H. pylori-negative patients, only 1 patient with atrophic gastritis was found in the 13-18 years age group. Representative pictures of normal, gastritis, and gastric mucosal precancerous lesions are shown in Figure 2.

As described in Table 4, active inflammation was observed in 16.04% (137/854) of the H. pylori-infected patients and only 3.73% (6/161) of the -uninfected patients. A significant difference was noticed between these two groups (χ2= 16.975, P < 0.001). But in the 1-4 years age group, there was no significant difference in inflammatory activity between the H. pylori-infected and -uninfected patients (13.64% vs 6.25%, χ2= 0.196, P = 0.658). Whereas in the 5-8 years, 9-12 years and 13-18 years age groups, the proportion of active inflammation in the H. pylori-positive patients was significantly higher than that in the H. pylori-negative patients (χ2= 4.901, P = 0.027; χ2= 3.987, P = 0.046; χ2= 6.012, P = 0.014).

| Age group | H. pylori+ | H. pylori- | ||||

| n | Active inflammation | Non-active inflammation | n | Active inflammation | Non-active inflammation | |

| 1-4 | 22 | 3 (13.64) | 19 (86.36) | 32 | 2 (6.25) | 30 (93.75) |

| 5-8 | 156 | 23 (14.74)a | 133 (85.26) | 43 | 1 (2.33) | 42 (97.67) |

| 9-12 | 383 | 52 (13.58)b | 331 (86.42) | 52 | 2 (3.85) | 50 (96.15) |

| 13-18 | 293 | 59 (20.14)c | 234 (79.86) | 34 | 1 (2.94) | 33 (97.06) |

| Total | 854 | 137 (16.04)d | 717 (83.96) | 161 | 6 (3.73) | 155 (96.27) |

The degree of neutrophil granulocyte infiltration with different H. pylori infection status is shown in Table 5. For the 854 infected patients, the proportions of absent, mild and moderate neutrophil granulocyte infiltration were 83.96%, 13.58% and 2.46%, respectively. While for the -uninfected patients, they were 96.27%, 3.73% and 0%, respectively. Compared with H. pylori-infected patients, the prevalence of neutrophil granulocyte infiltration in gastric mucosa was significantly higher than that in uninfected patients (Z = 4.319, P < 0.001). This difference between H. pylori-positive and -negative patients was also indicated in different age groups, with the exception of the 1-4 years age group.

| Age group | H. pylori+ | H. pylori+ | Z | P value | ||||||

| n | Absent | Mild | Moderate | n | Absent | Mild | Moderate | |||

| 1-4 | 22 | 19 (86.36) | 3 (13.64) | 0 (0) | 32 | 30 (93.75) | 2 (6.25) | 0 (0) | 0.912 | 0.362 |

| 5-8 | 156 | 133 (85.26) | 21 (13.46) | 2 (1.28) | 43 | 42 (97.67) | 1 (2.33) | 0 (0) | 2.212 | 0.027a |

| 9-12 | 383 | 331 (86.42) | 44 (11.49) | 8 (2.09) | 52 | 50 (96.15) | 2 (3.85) | 0 (0) | 2.009 | 0.045b |

| 13-18 | 293 | 234 (79.86) | 48 (16.38) | 11 (3.76) | 34 | 33 (97.06) | 1 (2.94) | 0 (0) | 2.456 | 0.014c |

| Total | 854 | 717 (83.96) | 116 (13.58) | 21 (2.46) | 161 | 155 (96.27) | 6 (3.73) | 0 (0) | 4.319 | < 0.001d |

As for lymphocyte infiltration, patients with H. pylori infection had more severe lymphocyte infiltration than uninfected patients (Z = 3.997, P < 0.001). In the H. pylori-positive group, 40.98%, 50.59% and 8.43% of mild, moderate and marked lymphocyte infiltration, respectively, were found, while in the H. pylori-negative group, the rates were 56.52%, 40.99% and 2.48%, respectively. In H. pylori-infected patients, the 9-12 years and 13-18 years age groups also showed more severe lymphocyte infiltration compared to the uninfected patients (Z = 2.539, P = 0.011; Z = 2.164, P = 0.030), but this difference was not significant between the 1-4 years and 5-8 years age groups (Z = 0.570, P = 0.569; Z = 1.737, P = 0.082) (Table 6). Representative pictures of gastric mucosal inflammatory cell infiltration are shown in Figure 2.

| Age group | H. pylori+ | H. pylori- | Z | P value | ||||||

| n | Mild | Moderate | Marked | n | Mild | Moderate | Marked | |||

| 1-4 | 22 | 10 (45.45) | 11 (50) | 1 (4.55) | 32 | 17 (53.12) | 14 (43.75) | 1 ( 3.13) | 0.57 | 0.569 |

| 5-8 | 156 | 67 (42.95) | 75 (48.08) | 14 (8.97) | 43 | 24 (55.81) | 18 (41.86) | 1 (2.33) | 1.737 | 0.082 |

| 9-12 | 383 | 161 (42.04) | 195 (50.91) | 27 (7.05) | 52 | 31 (59.62) | 20 (38.46) | 1 (1.92) | 2.539 | 0.01a |

| 13-18 | 293 | 112 (38.23) | 151 (51.54) | 30 (10.24) | 34 | 19 (55.88) | 14 (41.18) | 1 (2.94) | 2.164 | 0.03b |

| Total | 854 | 350 (40.98) | 432 (50.59) | 72 (8.43) | 161 | 91 (56.52) | 66 (40.99) | 4 (2.48) | 3.997 | < 0.00c |

In the current study, we investigated gastric mucosal inflammation and precancerous lesions in pediatric patients who were hospitalized for gastrointestinal symptoms. Among the 1015 children in our study who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, gastric mucosa precancerous lesions occurred in 4.33% of H. pylori-infected children, in which the proportions of atrophy, IM and dysplasia were 1.99%, 1.29%, 1.05%, respectively, significantly higher than findings from H. pylori-negative patients.

Under endoscopy evaluation, H. pylori-positive children presented more nodular gastritis, which is an important feature of H. pylori infection in children. But, the proportions of esophagitis, chronic superficial gastritis with erosions, chronic superficial gastritis with bile reflux and esophagitis were not significantly different between the infected and non-infected groups. The results also showed that children with H. pylori infection had a significantly higher incidence of gastric mucosal inflammation, and the degrees of neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltration were also much more serious than in H. pylori-negative children. These results are in line with previous studies that showed various degrees of inflammation in H. pylori-infected pediatric patients. For example, in 2017, Broide et al[27] showed that monocyte and neutrophil infiltration was more severe in the infected children group with chronic gastritis in Israel. One retrospective study of 196 children in Japan in 2006 also reached a similar conclusion[17].

The above results indicate that H. pylori infection is closely related to gastric mucosal inflammation, which might be the basis for development of gastric precancerous lesions, as both basic experiments and clinical investigations have confirmed that certain bacterial components, such as CagA and VacA, have detrimental effects on gastric epithelial cells. In addition, CagA is a bacterial oncoprotein, which can cause epithelial cell oncogenic transformation in vivo[28-30]. Therefore, future experiments for more detailed analysis of the H. pylori component on the pathogenesis of gastric precancerous lesions in children will be very helpful to understand the carcinogenesis and provide more rational for precise intervention and prevention.

The significance of this study is that it provides evidence to demonstrate that H. pylori infection is associated with the occurrence of precancerous lesions in pediatric patients, and these lesions increase with increase in age. Furthermore, the pediatric population might present in a similar way to adults with H. pylori infection, suggesting a healthcare threat to the pediatric patients. As eradication of H. pylori has been shown to prevent the development of atrophic gastritis, IM and gastric malignancy in adults[31,32], it is expected that proper intervention in pediatric patients could prevent the development of future diseases. Future investigation on the rationale and health economic evaluation would be required to provide more supporting evidence.

These results are also in line with previous reports. For example, in 2006, a study of 131 H. pylori-infected children in Japan showed that the proportion of gastric antrum atrophy was 10.7%[17]. In a 2020 study in Romania, the H. pylori infection rate was 33.06% (82/248); among 82 infected children, 9 (11%) had atrophic gastritis and 2 (2.4%) had IM[33]. A survey of 1634 children in China in 2014 found that atrophic gastritis accounted for 4.4% (23/524 cases) of the H. pylori-infected children[16]. However, one Austrian study in 2011 found gastric atrophy was rare (1/84) in children infected with H. pylori[34]. In addition, no gastric atrophy was found in 66 French children infected with H. pylori in 2009[35], and no precancerous lesions were found in 132 gastric biopsies from 22 symptomatic H. pylori-infected children in a 2009 study in Brazil[36].

As H. pylori-induced disease presentations are mostly present in adulthood, the presence of precancerous lesions in children unveiled a critical issue that was largely neglected previously[13,15,37]. Although there are still controversies on the significance and consequence of H. pylori-induced serious gastric mucosal lesions in children[13], current consensus reports from the Asia-Pacific region[38], China[8,39] and Japan[18] have indicated that H. pylori should be eradicated when such conditions are present, and their family members should also receive screening and treatment if confirmed positive. It is hypothesized that gastric mucosal atrophy and IM in children and adolescents might be present in a similar way to adult H. pylori infection and is probably more common in areas with high H. pylori infection rates than previously thought.

One of the major shortfalls of this retrospective study is that the rapid urease test was the primary test used to detect H. pylori infection because 13C-urea breath test, serological H. pylori antibody tests and stool antigen tests were not available for more accurate diagnosis. This could result in the underestimation of H. pylori infection rates or have false negative results in the uninfected children group. Two perplexing results might be attributed to these drawbacks as there are 8 duodenal ulcer patients (Table 1) and few patients had active gastric inflammation (Tables 4 and 5) in the H. pylori-negative group. Due to the strong relationship of H. pylori in causing these diseases, it is unlikely these patients were not infected by H. pylori. Furthermore, it is likely because of the limitation of the rapid urease test, which is unable to detect patchy distribution of H. pylori in the stomach. Therefore, future studies will be required to confirm these discrepancies. Even with these drawbacks, the overall conclusions and significance of the investigation were not affected.

Although the current work provides novel points on H. pylori-induced gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in children, due to its retrospective nature, the investigation has limitations. First, this study only discussed the relationship between H. pylori infection and gastric mucosa precancerous lesions and was unable to analyze the effects of different genotypes of infected H. pylori strains. Therefore, more detailed information on H. pylori strains are not available. Nonetheless, our previous work demonstrated that type I H. pylori (CagA- and VacA-positive) is the primary type of H. pylori infection in this region[40]. It is expected that the pediatric population is similar to the adult population. Second, not all cases had biopsy specimens from both the gastric antrum and body. Some of the precancerous lesions and H. pylori infection may have been missed due to histopathological presentation of the stomach, and patchy H. pylori infection status in other places of the stomach were unable to be examined. In the future, multiple biopsies might be helpful to overcome these drawbacks. Third, this was a single-center, retrospective analysis, and all the children were hospitalized due to gastrointestinal symptoms, which may be the reason why the infection rate was much higher than among the general population. In the future, large-scale investigations in the general public and multi-center, prospective and randomized control analyses are needed to comprehensively assess the risk of H. pylori infection and precancerous lesions in children and adolescents in order to understand the overall precancerous lesions of H. pylori-infected pediatric patients.

Our results show that H. pylori-infected children have more active inflammation and inflammatory cell infiltration in the gastric mucosa, and infection rate increases with patient age. The incidence of precancerous lesions in H. pylori-infected patients is also significantly higher compared to that in -uninfected patients. Although the percentage is only 4.33%, it provides an alarming alert and call for further investigation and intervention for this population group.

Chronic Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection causes gastric mucosal precancerous lesions and gastric cancer in adult patients. It remains to be determined, however, whether gastric mucosal precancerous lesions may also occur in children and adolescents, as this remains an important issue for clinical intervention.

Investigating the relationship between H. pylori infection and gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in pediatric patients will provide important evidence on whether intervention should be offered to prevent related disease development in this population group.

H. pylori infection status, gastric mucosal inflammation and gastric precancerous lesions in hospitalized pediatric patients were investigated in central China.

We retrospectively enrolled 1015 symptomatic pediatric patients to analyze their clinical and path-ological data. The endoscopic and histological findings, occurrence of gastric mucosal precancerous lesions, inflammatory activity and degree of inflammatory cell infiltration were analyzed between H. pylori-positive and -negative patient groups.

The overall H. pylori infection rate was 84.14% for the 1015 enrolled pediatric patients, and infection rate increased with age. The incidence of gastric mucosal precancerous lesions in H. pylori-infected children was 4.33%, which was significantly higher than that in H. pylori-negative children. Infected patients showed more active inflammation as well as more severe inflammatory cell infiltration compared to the non-infected patients. Additionally, endoscopy revealed that the most common presentation was antral nodularity in H. pylori-positive patients, whereas superficial gastritis was a marked feature for H. pylori-negative patients.

In children and adolescents, gastric mucosal precancerous lesions occurred in 4.33% of H. pylori-infected patients in central China. The data revealed an obvious critical issue that requires future investigation and intervention for this population group.

The results provide insights on H. pylori infection status and its relationship with gastric mucosal precancerous in symptomatic pediatric patients in central China. Further investigation and intervention for related disease prevention are required in this population group.

The authors are grateful to the staff of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University for their valuable assistance in this work.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kirkik D, Turkey; Miftahussurur M, Indonesia S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Yuan C, Adeloye D, Luk TT, Huang L, He Y, Xu Y, Ye X, Yi Q, Song P, Rudan I; Global Health Epidemiology Research Group. The global prevalence of and factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Park JS, Jun JS, Seo JH, Youn HS, Rhee KH. Changing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021;64:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li XC, Wang HD, Zhang N, Wang YP, Zhou YN. Systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological investigation of Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents in China. Linchuang Erke Zazhi. 2017;35:782-787. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Seo JH, Bortolin K, Jones NL. Review: Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Helicobacter. 2020;25 Suppl 1:e12742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Subsomwong P, Miftahussurur M, Uchida T, Vilaichone RK, Ratanachu-Ek T, Mahachai V, Yamaoka Y. Prevalence, risk factors, and virulence genes of Helicobacter pylori among dyspeptic patients in two different gastric cancer risk regions of Thailand. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0187113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li M, Sun Y, Yang J, de Martel C, Charvat H, Clifford GM, Vaccarella S, Wang L. Time trends and other sources of variation in Helicobacter pylori infection in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2020;25:e12729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ren S, Cai P, Liu Y, Wang T, Zhang Y, Li Q, Gu Y, Wei L, Yan C, Jin G. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 8. | Liu WZ, Xie Y, Lu H, Cheng H, Zeng ZR, Zhou LY, Chen Y, Wang JB, Du YQ, Lu NH; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Study Group on Helicobacter pylori and Peptic Ulcer. Fifth Chinese National Consensus Report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2220] [Cited by in RCA: 1973] [Article Influence: 246.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Jones NL, Koletzko S, Goodman K, Bontems P, Cadranel S, Casswall T, Czinn S, Gold BD, Guarner J, Elitsur Y, Homan M, Kalach N, Kori M, Madrazo A, Megraud F, Papadopoulou A, Rowland M; ESPGHAN, NASPGHAN. Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Management of Helicobacter pylori in Children and Adolescents (Update 2016). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:991-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Correa P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3554-3560. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Miftahussurur M, Sharma RP, Shrestha PK, Maharjan RK, Shiota S, Uchida T, Sato H, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Gastric Mucosal Atrophy in Two Ethnic Groups in Nepal. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:7911-7916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dimitrov G, Gottrand F. Does gastric atrophy exist in children? World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6274-6279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Boukthir S, Mrad SM, Kalach N, Sammoud A. Gastric atrophy and Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009;30:107-109. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Villarreal-Calderon R, Luévano-González A, Aragón-Flores M, Zhu H, Yuan Y, Xiang Q, Yan B, Stoll KA, Cross JV, Iczkowski KA, Mackinnon AC Jr. Antral atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and preneoplastic markers in Mexican children with Helicobacter pylori-positive and Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18:129-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yu Y, Su L, Wang X, Xu C. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and pathological changes in the gastric mucosa in Chinese children. Intern Med. 2014;53:83-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kato S, Nakajima S, Nishino Y, Ozawa K, Minoura T, Konno M, Maisawa S, Toyoda S, Yoshimura N, Vaid A, Genta RM. Association between gastric atrophy and Helicobacter pylori infection in Japanese children: a retrospective multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P; faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1322] [Cited by in RCA: 1173] [Article Influence: 117.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Osaki T, Konno M, Yonezawa H, Hojo F, Zaman C, Takahashi M, Fujiwara S, Kamiya S. Analysis of intra-familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese families. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rothenbacher D, Winkler M, Gonser T, Adler G, Brenner H. Role of infected parents in transmission of Helicobacter pylori to their children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:674-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kienesberger S, Perez-Perez GI, Olivares AZ, Bardhan P, Sarker SA, Hasan KZ, Sack RB, Blaser MJ. When is Helicobacter pylori acquired in populations in developing countries? Gut Microbes. 2018;9:252-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jaramillo-Rodríguez Y, Nares-Cisneros J, Martínez-Ordaz VA, Velasco-Rodríguez VM, Márquez FC, Manríquez-Covarrubias LE. Chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori in Mexican children: histopathological patterns. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2011;14:93-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Okuda M, Lin Y, Kikuchi S. Helicobacter pylori Infection in Children and Adolescents. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1149:107-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Whitney AE, Guarner J, Hutwagner L, Gold BD. Helicobacter pylori gastritis in children and adults: comparative histopathologic study. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liu S, Chen Q, Quan P, Zhang M, Zhang S, Guo L, Sun X, Wang C. Cancer incidence and mortality in Henan province, 2012. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016;28:275-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3221] [Cited by in RCA: 3545] [Article Influence: 122.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 27. | Broide E, Richter V, Mendlovic S, Shalem T, Eindor-Abarbanel A, Moss SF, Shirin H. Lymphoid follicles in children with Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:239-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Myint T, Miftahussurur M, Vilaichone RK, Ni N, Aye TT, Subsomwong P, Uchida T, Mahachai V, Yamaoka Y. Characterizing Helicobacter pylori cagA in Myanmar. Gut Liver. 2018;12:51-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hatakeyama M. Linking epithelial polarity and carcinogenesis by multitasking Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA. Oncogene. 2008;27:7047-7054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kong YJ, Yi HG, Dai JC, Wei MX. Histological changes of gastric mucosa after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5903-5911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 441] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Domșa AT, Lupușoru R, Gheban D, Șerban R, Borzan CM. Helicobacter pylori Gastritis in Children-The Link between Endoscopy and Histology. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hoepler W, Hammer K, Hammer J. Gastric phenotype in children with Helicobacter pylori infection undergoing upper endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kalach N, Papadopoulos S, Asmar E, Spyckerelle C, Gosset P, Raymond J, Dehecq E, Decoster A, Creusy C, Dupont C. In French children, primary gastritis is more frequent than Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1958-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Langner M, Machado RS, Patrício FR, Kawakami E. Evaluation of gastric histology in children and adolescents with Helicobacter pylori gastritis using the Update Sydney System. Arq Gastroenterol. 2009;46:328-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kara N, Urganci N, Kalyoncu D, Yilmaz B. The association between Helicobacter pylori gastritis and lymphoid aggregates, lymphoid follicles and intestinal metaplasia in gastric mucosa of children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50:605-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Mahachai V, Vilaichone RK, Pittayanon R, Rojborwonwitaya J, Leelakusolvong S, Maneerattanaporn M, Chotivitayatarakorn P, Treeprasertsuk S, Kositchaiwat C, Pisespongsa P, Mairiang P, Rani A, Leow A, Mya SM, Lee YC, Vannarath S, Rasachak B, Chakravuth O, Aung MM, Ang TL, Sollano JD, Trong Quach D, Sansak I, Wiwattanachang O, Harnsomburana P, Syam AF, Yamaoka Y, Fock KM, Goh KL, Sugano K, Graham D. Helicobacter pylori management in ASEAN: The Bangkok consensus report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:37-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ding SZ, Du YQ, Lu H, Wang WH, Cheng H, Chen SY, Chen MH, Chen WC, Chen Y, Fang JY, Gao HJ, Guo MZ, Han Y, Hou XH, Hu FL, Jiang B, Jiang HX, Lan CH, Li JN, Li Y, Li YQ, Liu J, Li YM, Lyu B, Lu YY, Miao YL, Nie YZ, Qian JM, Sheng JQ, Tang CW, Wang F, Wang HH, Wang JB, Wang JT, Wang JP, Wang XH, Wu KC, Xia XZ, Xie WF, Xie Y, Xu JM, Yang CQ, Yang GB, Yuan Y, Zeng ZR, Zhang BY, Zhang GY, Zhang GX, Zhang JZ, Zhang ZY, Zheng PY, Zhu Y, Zuo XL, Zhou LY, Lyu NH, Yang YS, Li ZS; National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (Shanghai), Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention & Treatment Alliance of China (GECA), Helicobacter pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, and Chinese Alliance for Helicobacter pylori Study. Chinese Consensus Report on Family-Based Helicobacter pylori Infection Control and Management (2021 Edition). Gut. 2022;71:238-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yuan L, Zhao JB, Zhou YL, Qi YB, Guo QY, Zhang HH, Khan MN, Lan L, Jia CH, Zhang YR, Ding SZ. Type I and type II Helicobacter pylori infection status and their impact on gastrin and pepsinogen level in a gastric cancer prevalent area. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:3673-3685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |