Published online Jan 14, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i2.188

Peer-review started: March 26, 2021

First decision: June 14, 2021

Revised: June 25, 2021

Accepted: December 31, 2021

Article in press: December 31, 2021

Published online: January 14, 2022

Processing time: 291 Days and 0.3 Hours

Protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) is a member of the PKC family, and its implications have been reported in various biological and cancerous processes, including cell proliferation, cell death, tumor suppression, and tumor progression. In liver cancer cells, accumulating reports show the bi-functional regulation of PKCδ in cell death and survival. PKCδ function is defined by various factors, such as phosphorylation, catalytic domain cleavage, and subcellular localization. PKCδ has multiple intracellular distribution patterns, ranging from the cytosol to the nucleus. We recently found a unique extracellular localization of PKCδ in liver cancer and its growth factor-like function in liver cancer cells. In this review, we first discuss the structural features of PKCδ and then focus on the functional diversity of PKCδ based on its subcellular localization, such as the nucleus, cell surface, and extracellular space. These findings improve our knowledge of PKCδ involvement in the progression of liver cancer.

Core Tip: Protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) plays multifunctional roles in various cancers, including liver cancer. PKCδ has been shown to exert pleiotropic functions through various stimuli responsiveness, post-translational modifications, and subcellular localization. Recently, we found that PKCδ is secreted extracellularly and resides on the cell surface of liver cancer cells, which contributes to tumorigenesis. In this review, we focus on the localization of PKCδ to discuss its characteristic localization patterns and functions in liver cancer, and outline the involvement of PKCδ localized intra- and extracellularly with distinct functions in the progression of liver cancer.

- Citation: Yamada K, Yoshida K. Multiple subcellular localizations and functions of protein kinase Cδ in liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(2): 188-198

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i2/188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i2.188

The protein kinase C (PKC) family of serine/threonine kinase proteins in mammals, comprising the classical PKC (cPKC), novel PKC (nPKC), and atypical PKC (aPKC) subfamilies, is one of the defining families of AGC kinases[1,2]. To date, 10 isoforms of PKC have been identified in humans, including four cPKCs (PKCα, -βI, -βII, and -γ), four nPKCs (PKCδ, -ε, -η, and -θ), and two aPKCs (PKCζ and -λ/ι)[2,3]. PKC activation depends on the conformational activation of certain intracellular factors. Notably, PCK activation is regulated not only by binding to lipid factors, such as diacylglycerol (DAG) and phorbol esters, but also by protein phosphorylation[4]. PKCδ is often phosphorylated at several Tyr residues by various types of stimulations, including DNA-damaging reagents and oxidative stress[5,6]. Kinases that phosphorylate PKCδ at Tyr include the Src family of tyrosine kinases (e.g., Src, Fyn, Lyn, and Lck) and c-Abl[6].

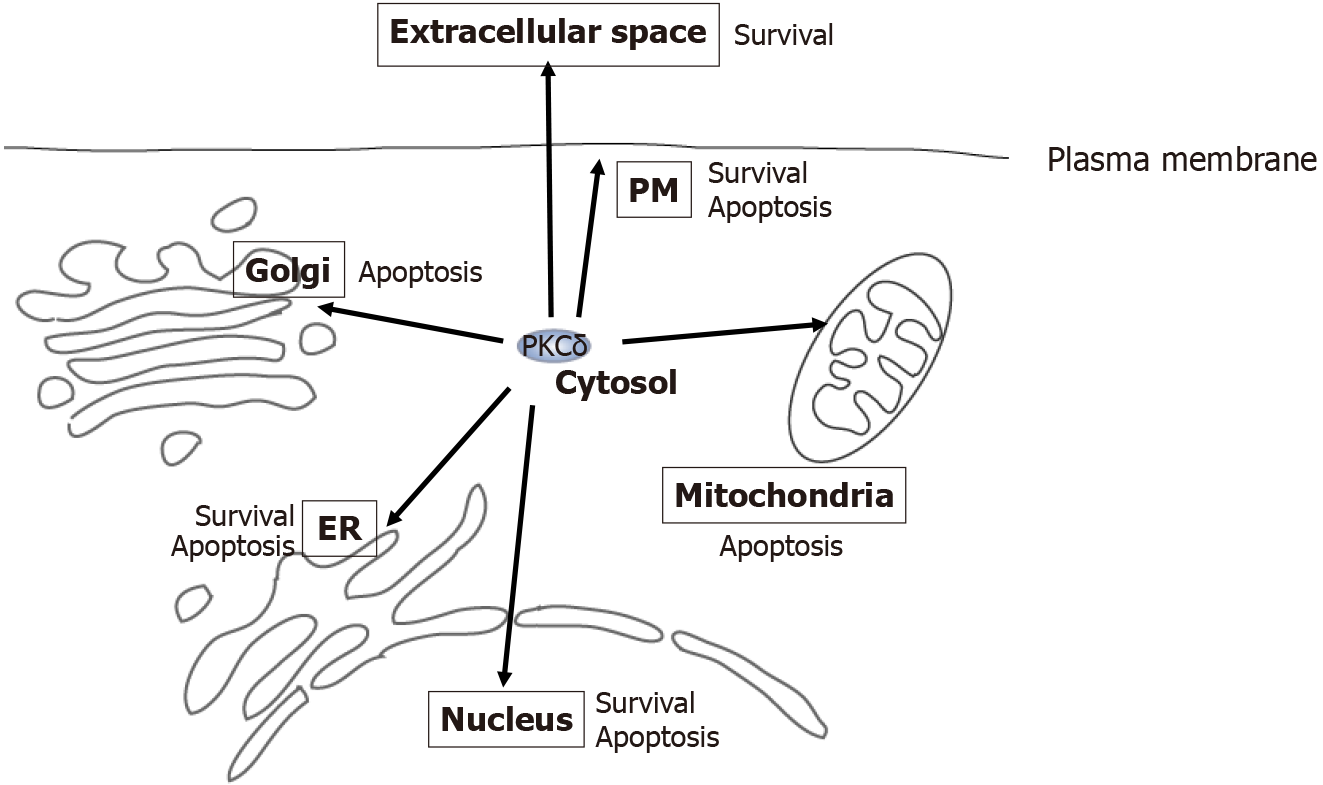

Among PKC families, PKCδ is a unique non-signal peptide-containing intracellular protein that has been reported to translocate to a diverse range of distributions, including the cytosol, nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi, mitochondria, and plasma membrane, in response to different stimuli and cell types[8]. For example, a nuclear localization signal (NLS) was identified in the catalytic domain of PKCδ, which is necessary for the transport of PKCδ across the nuclear pore. Nuclear localization of PKCδ is associated with pro-apoptotic functions. Phosphorylation also affects the subcellular localization of PKCδ and its activation. Our recent study revealed that cytosolic PKCδ translocates to the extracellular space and acts as a growth factor for liver cancer cells or tumors[9]. In this review, we summarize studies reported to date regarding the intracellular function of PKCδ in cancerous phenotypes of liver cancer. We then focus on and discuss the relationship with subcellular localizations, which exist in extracellular and intracellular locations, and the functions of PKCδ. Increased knowledge on where PKCδ protein is localized and how it functions in living cells allows a more profound understanding of the functional diversity of PKCδ.

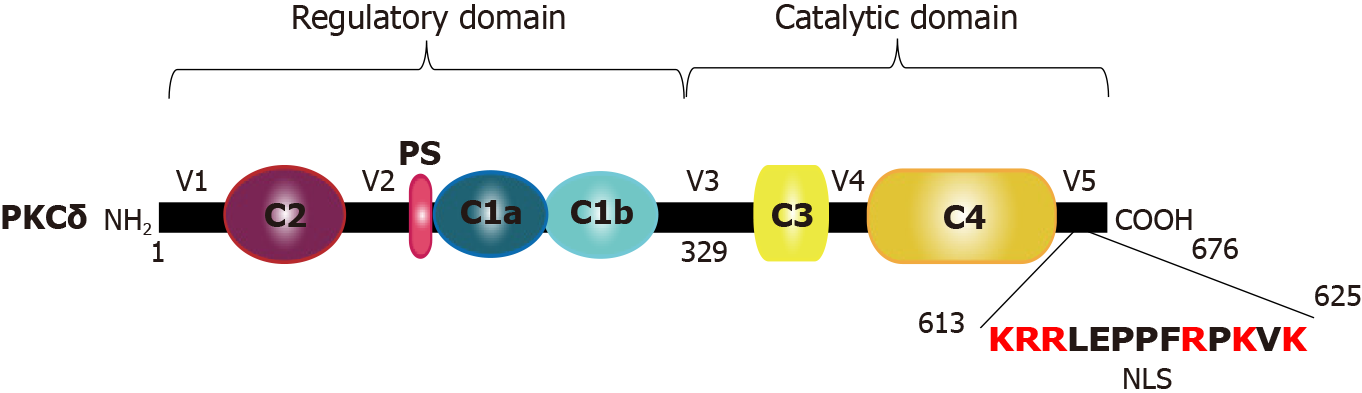

PKCδ comprises an N-terminal regulatory domain and a C-terminal kinase core domain[5]. The C-terminal catalytic domain of PKC is conserved between isoforms and includes ATP- and substrate-binding sites and a kinase core[10,11]. The N-terminal regulatory domain is much less conserved and contains specific motifs for each isoform that are activated in response to unique signals. The regulatory modules in this N-terminal domain include the pseudosubstrate motif and C1 and C2 domains, which bind to Ca2+ and DAG. The affinity of the C1 and C2 domains for Ca2+ and DAG determines the cofactor requirements for the activation of specific PKC isoforms. cPKCs have functional C1 and C2 domains that bind to both Ca2+ and DAG[12-14], whereas nPKCs have a functional C1 domain that binds to DAG alone and a non-functional C2 domain, rendering these kinases independent of Ca2+ for activation[15].

Generally, upon PKC activation, growth factors and G protein-coupled receptors trigger the hydrolysis of membrane lipids by recruiting phospholipase C[16,17]. Phospholipase C generates DAG and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate through the hydrolysis of membrane phosphoinositol. In response to DAG, PKC is translocated to the lipid membrane via the C1 domain, enabling interaction with its substrates and the phosphorylation response[18].

PKCδ confers distinct allosteric regulation via protein binding to the C1, C2, and V5 domains, tyrosine phosphorylation, and the removal of the regulatory domain by caspase cleavage (Figure 1). In particular, various reports have identified that a variety of tyrosine phosphorylation sites affect cellular functions. For example, many studies have demonstrated that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ plays a critical role in cell death in response to apoptotic stimuli. Tyrosine residues important in the context of apoptosis include Tyr64, Tyr155, Tyr187, Tyr311, Tyr332, and Tyr512[18-20]. Furt

Studies on PKCδ-/- mice have confirmed the pro-apoptotic role of this molecule in response to several stimuli, such as DNA damage. Although these mice developed normally and were fertile, increased B cell proliferation was observed[21]. Smooth muscle cells derived from PKCδ-/- mouse aortas were also shown to be resistant to cell death in response to several stimuli. Hence, these studies with PKCδ-/- mice dem

PKC also binds to and is activated by tumor-promoting phorbol esters[4]. Therefore, PKC is considered a tumor-promoting protein. However, it has been reported that persistent treatment with phorbol esters causes degradation or downregulation of PKC[3,22-24]. In particular, PKCδ has been reported to enhance ubiquitin proteasomal degradation upon activation of PKCδ by lipids. Furthermore, accumulating evidence on PKCδ in cancer has shown that downregulation, rather than activation, of PKCδ is associated with tumor progression. Therefore, PKCδ is believed to act as a tumor suppressor because its downregulation facilitates tumor promotion and causes cell cycle arrest or induces apoptosis in response to various stimuli, such as H2O2, ceramide, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), ultraviolet radiation, cisplatin, and etoposide[22,25-27]. In fact, the PKCδ gene is deleted in many cancers[28]. Ectopic expression of PKCδ has been shown to decrease the anchorage-independent growth of NIH3T3 cells and reverse the transformation of rat fibroblasts and colonic epithelial cells by Src. Low levels of PKCδ have been reported in colon cancer, and overexpression of PKCδ suppresses the neoplastic phenotype of colon cancer cells[25]. A recent report suggested that PKCδ is lost in human squamous cell carcinoma due to transcriptional repression[29]. PKCδ has also been reported to decrease cell migration in breast cancer cells, whereas knockout of the PKCδ gene increases cell migration in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. These studies strongly support the role of PKCδ in tumor suppression.

Multiple reports suggest that PKCδ is responsible for apoptotic signaling in liver cancer cells (Table 1). In sorafenib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, PKCδ activation was shown to induce cellular apoptosis via p38 activation[30]. Annexin A3 (ANXA3) interacts with PKCδ and thereafter suppresses PKCδ/p38-associated apoptosis and activates autophagy for cell survival. Thus, inhibition of ANXA3 by a monoclonal antibody is likely to impair cell survival and tumor growth. Although FTY720, a synthetic sphingosine immunosuppressor, has been known to have antitumor effects on HCC cells, PKCδ activation occurs in FYT720-treated HCC cells. FTY720 is thought to activate PKCδ via the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent caspase 3-dependent cleavage to induce apoptosis. The relationship between intracellular activation of PKCδ and apoptosis in HCC cells has also been reported in the antitumor mechanism of an antagonist of FZD7, which is a membrane receptor overexpressed in HCC[31]. These lines of evidence suggest that PKCδ activation is not favorable for malignant transformation in liver cancer and may be inactivated in these cells.

| Response | Localization | Function | Mechanisms | Ref. |

| ANXA3 expression | Cytosol/plasma membrane | Interacts with PKCδ and inhibits apoptosis | p38MAPK activation | [30] |

| ROS | Nucleus | Activates PKCδ and induces apoptosis | Activates caspase 3 and induces cleavage of PKCδ | [31] |

| Claudin-1 | Cytosol/plasma membrane | Enhances the ability of cell migration/invasion | Induces c-Abl-PKCδ signaling | [33] |

| mtROS | Plasma membrane | Induces gene expression for cell migration | Triggers oxidation of HSP60 and then induces MAPK activation | [34] |

| HIF-2α expression | Cytosol/plasma membrane | Induces cell migration | Phosphorylates PKCδ at Tyr311 | [35] |

| HSP27 expression | Cytosol/plasma membrane | Inversely correlates with tumor malignancy | p38MAPK activation by PKCδ induces phosphorylation of HSP27 | [36] |

| No response | Extracellular space/cell surface | Enhances cell proliferation | Activates MAPK signaling | [9] |

Many studies have shown that PKCδ promotes the survival of multiple types of cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and liver cancer.

PKCδ has been reported to induce signal survival. In fact, PKCδ promotes cell survival via several well-known pro-survival pathways, including NF-κB, Akt, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). It has been reported that PKCδ inhibits apoptosis by inhibiting apoptosis protein-2 and FLICE-like inhibitory protein via NF-κB[32].

Numerous publications have reported that PKCδ is actively involved in the promotion of liver cancer, including cell migration, invasion, and tumor stage (Table 1). For example, claudin-1, a member of the tetraspanin family, plays a critical role in the acquisition of invasive capacity in human liver cells, and c-Abl-PKCδ signaling is important for malignant progression induced by claudin-1[33]. This c-Abl-PKCδ signaling pathway was shown to activate MMP-2, a key factor in cell migration and invasion. The cross talk between PKC and ROS may induce mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation for cell migration and progression. Mandal et al[34] found that activation of PKCδ generated mitochondrial ROS triggers the oxidation of heat shock protein 60 (HSP60), a chaperone protein in the mitochondria, which induces the activation of ERK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in the cytosol, resulting in gene expression leading to migration in liver cancer. PKCδ and hypoxia have also been reported to be associated with cell migration in liver cancer. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2α expression regulates CUB domain-containing protein 1, which stimulates the phosphorylation of PKCδ at Tyr311 to induce malignant migration in various cancer cells, such as liver cancer cells[35]. Furthermore, the levels of HSP27 are inversely correlated with tumor stage, as per the tumor, node and metastasis classification, in patients with HCC. Takai et al[36] showed that PKCδ activation regulates the phosphorylation of HSP27 via p38 MAPK.

There is supportive evidence that PKCδ acts as a tumor promoter in many types of cancers. For example, the mRNA levels of PKCδ were higher in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive tumors than in ER-negative tumors, and an increase in PKCδ mRNA was associated with reduced overall survival[37]. PKCδ knockdown decreased the survival of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells[38]. Overexpression of PKCδ was also observed in human ductal pancreatic carcinomas compared to its normal counterparts. PKCδ has been reported to be associated with melanoma cell metastasis[39]. A recent study demonstrated that integrin αvβ3-mediated invasion of melanoma cells is mediated via PKCα and PKCδ.

PKCδ is translated on the ribosome in the cytosol and generates its inactive cytosolic form. Similar to other PKC families, in response to DAG, PKCδ is also translocated to the plasma membrane via the C1 domain, which exerts a subsequent phosphorylation response. PKCδ activation is also required for Akt activation by Ras[40] (1-98). Activating mutations with Ras or PI3K increases PKCδ levels and induces Akt activation. PKCδ also induces ERK1/2 activation[41,42]. Akt and ERK1/2 activation have been implicated in the PKCδ-mediated increase in anchorage-independent growth and resistance of pancreatic ductal cancer cells to apoptotic stimuli[43]. Conversely, cytosolic PKCδ reportedly triggers apoptosis by activating p38 MAPK to inhibit Akt[8], indicating that PKCδ activation can behave as both a prosurvival and pro-apoptotic factor. Liver damage has been reported to induce inflammation and PKCδ translocation to the plasma membrane[44,45]. PKCδ activation has been observed in the tissues of patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and in a mouse model of hepatic cirrhosis[46-49].

Importantly, PKCδ is a PKC isoform that has been identified as a substrate for caspase-3[50]. Cleavage of PKCδ by caspase-3 separates the regulatory domain and catalytic fragment to allow constitutive activation of PKCδ even in the absence of any co-factors[22] and then translocates to the nucleus, where the catalytic fragment of PKCδ induces apoptosis[22]. Others and we have shown that full-length or fragmented PKCδ is translocated to the nucleus by transiting the nuclear pore[6,51]. Nuclear PKCδ interacts with and phosphorylates its substrates such as α-Abl, p53, p73, lamin B, Rad9, topoisomerase II, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP-K), and DNA-dependent protein kinase[22,52-54]. Moreover, nuclear PKCδ regulates the tran

Upon oxidative stress, we previously showed that PKCδ associates with and activates IKKα in the nucleus[55]. Although IKKα activates NF-κB by phosphorylating IκB in the cytoplasm, which leads to prosurvival signaling, PKCδ-mediated IKKα activation at the nucleus causes phosphorylation of p53 at Ser20; however, it does not affect NF-κB activation.

The tumor suppressor p53 is a master regulator of cellular processes, such as cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, or apoptosis[56,57]. Several studies have suggested that p53 is located downstream of PKCδ. In response to genotoxic stress, PKCδ phosphorylates p53 at Ser46 to trigger p53-mediated apoptosis.

In the nucleus, PKCδ also regulates p53 expression by increasing p53 transcription. We previously reported that PKCδ interacts with the death-promoting transcription factor Btf to induce Btf-mediated p53 gene transcription and apoptosis[58]. In addition, TNF-α treatment induces translocation of PKCδ into the nucleus[59]. PKCδ can bind to the NF-κB RelA subunit and subsequently induce the transactivation of p65/RelA[59]. These findings demonstrate that NF-κB is involved in PKCδ-mediated TNF/TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) resistance. PKCδ inhibition or knockdown decreased NF-κB expression and sensitized MCF7 cells to TNF/TRAIL-induced cell death[60].

Bax and Bak are pro-apoptotic factors, and the Bcl-2 family regulates mitochondrial membrane permeability to induce apoptosis[61]. Upon exposure to ionizing radiation, Bax and Bak are activated via the c-Abl-PKCδ-p38 pathway to trigger mitochondrial cell death[30,62]. Mcl-1, an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, is a direct target of PKCδ. The catalytic fragment of PKCδ phosphorylates Mcl-1 and degrades it, leading to cell death. During the early stages of hypoxic stress, PKCδ induces autophagy via JNK-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 to dissociate the Bcl-2/beclin-1 complex, and prolonged hypoxic stress induces PKCδ cleavage[63].

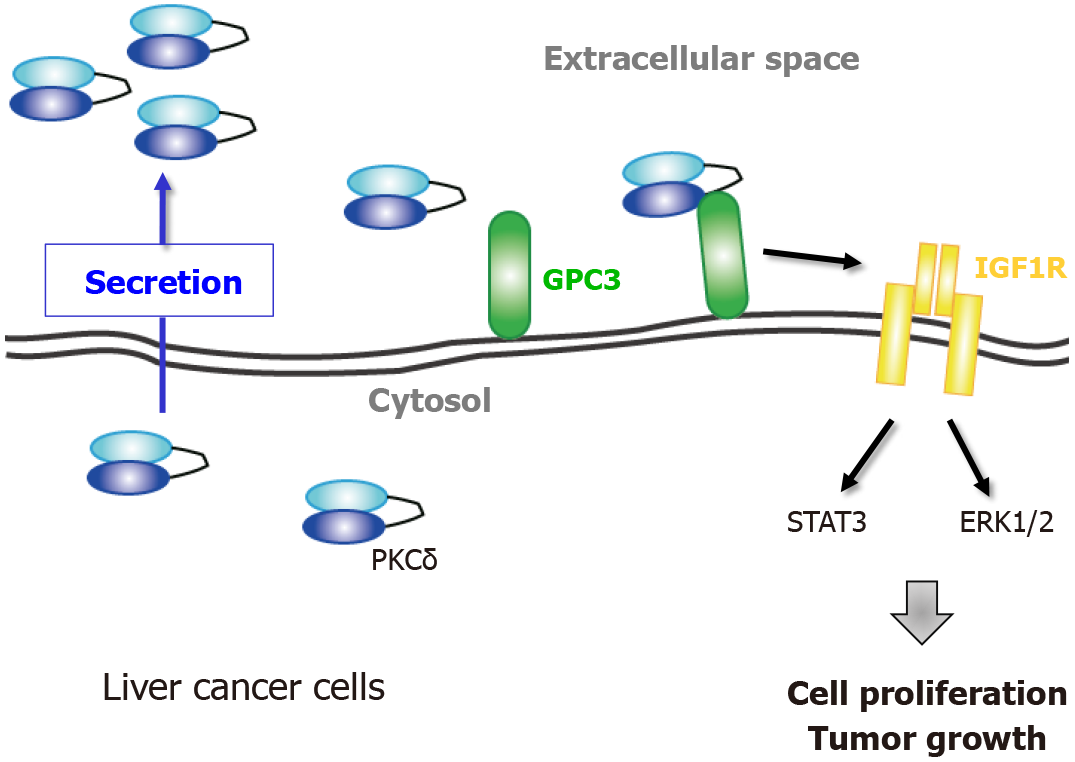

We recently showed that PKCδ is localized at the cell surface of liver cancer cell lines (Figure 2). Cell surface PKCδ was found to be anchored by other cell surface proteins, such as heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). Some growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factors, vascular endothelial growth factor, and hepatocyte growth factor[64,65] have cationic amino acid clusters that can interact with heparan sulfate, which is composed of one or more unbranched anionic polysaccharide(s) known as glycosaminoglycans[65-67]. The cationic amino acid clusters closely resemble the NLS of intracellular proteins[68]. In fact, extracellular NLS-containing proteins, such as importin α1, huRNP-K, and PKCδ are detected at the cell surface of human cells[9,69,70]. These extracellular NLS-containing proteins are more likely to be located at the cell surface by binding to HSPGs.

Furthermore, glypican3, a liver cancer-specific HSPG, was identified as a receptor for cell surface PKCδ[71]. Both Cheng et al[72,73] and we showed that GPC3 regulates the activation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R)[9]. In fact, we found that extracellular PKCδ induces activation of IGF1R via association with GPC3 and its downstream signaling molecules, such as ERK1/2 and STAT3. Thus, these lines of evidence strongly suggest that cell surface PKCδ acts as a growth factor. In addition, we showed that anti-PKCδ monoclonal antibody (mAb) inhibits the proliferation and tumorigenesis of liver cancer cells, but not PKCδ-CRISPR knockout cells. Thus, cell surface PKCδ may be a potential therapeutic target for liver cancer.

We also found that PKCδ is secreted into the extracellular space in liver cancer[9]. Extracellular accumulation of PKCδ was detected in different liver cancer cell lines but not in hepatocytes, suggesting that PKCδ secretion may be specific to liver cancer cells. Interestingly, our proteomics study showed that PKC, rather than PKCδ, was not detected in the culture medium of liver cancer cell lines. This means that PKCδ is a unique isoform of the PKC superfamily that is secreted extracellularly. Furthermore, higher levels of PKCδ were detected in the serum of patients with liver cancer, but not in patients with chronic hepatitis, hepatic cirrhosis, or healthy donors. This increase in serum PKCδ levels was also noted in a limited number of AFP- and PIVKA-II-negative liver cancer patients. Based on these clinical data, we propose that serum PKCδ may be a novel biomarker for liver cancer.

Recently, we and other groups have reported the extracellular localization of proteins with no signal peptide-containing proteins, such as FGF1, FGF2, HMGB1, hnRNP-K, importin α1, and IL-1β[69,70,74-77]. Secretion of these proteins is referred to as unconventional secretion[74,78]. Since the PKCδ gene does not encode a signal peptide, the extracellular secretion of PKCδ is also categorized as unconventional secretion. PKCδ has been shown to be full-length in the extracellular space and continues to be released from growing cells[9]. Many studies have reported that IL-1β secretion often occurs in immune cells after induction of inflammatory stimulation[77,79,80]. There are some differences in the secretion modes between immune and cancer cells. Unlike immune cells (IL-1β), liver cancer cells constitutively secrete importin α1 and PKCδ even under physiological culture conditions (using 10% FBS medium)[9,69]. Conversely, some features were common between immune and liver cells, including the induction of unconventional secretion by ATP treatment[81] and independent of brefeldin A, an inhibitor in the “conventional” secretion pathway of signal peptide-containing proteins[82].

We found that PKCδ secretion was initiated in the cytosol. Phorbol ester treatment inhibited PKCδ secretion, and the NLS active mutant was not secreted into the extracellular space. In fact, secreted PKCδ showed a lower level of phosphorylation (Tyr311 and Thr505). These lines of evidence support the possibility that cytosolic PKCδ, as a starting point for extracellular localization, could contribute to tumor progression in liver cancer.

A previous study has shown that PKCδ is translocated to the ER in response to ER stress and interacts with ER-bound c-Abl[83]. This PKCδ-c-Abl complex consequently moves to the mitochondria to trigger apoptosis[83]. It has been reported that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ is associated with this interaction with c-Abl[84]. The chemical inhibitor rottlerin blocks the translocation of the PKCδ-c-Abl complex from the ER to the mitochondria, which confers protection against apoptosis[83]. Another ER protein, p23 (Tmp21), interacts with PKCδ, which enables the retention of PKCδ in the ER[85]. Translocation of PKCδ to the ER has also been reported in cells with Sindbis virus and in glioma cells treated with TRAIL, where PKCδ exerts an anti-apoptotic effect. Furthermore, a small amount of PKCδ has been observed in the Golgi apparatus. Ceramide or IFN-γ stimulation has been shown to translocate PKCδ to the Golgi apparatus, which is associated with ceramide-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells.

The apoptotic and survival functions of PKCδ are defined by cell and tissue types and their cellular conditions (Figure 3). In response to cellular stresses, PKCδ may be translocated to different organelles (including the cytosol and extracellular space), where PKCδ executes distinct functions in each location. Among the many types of tissues and cells, liver cancer cells have the most patterns of localization of PKCδ, including conventional intracellular and extracellular localization. Notably, extracellular PKCδ is involved in the tumorigenesis of liver cancer; therefore, it is a promising novel diagnostic and therapeutic target for liver cancer. Additional studies are required to elucidate further the various roles of PKCδ in liver cancer cells, which are dependent on the expression, subcellular distribution, and tumor microenvironment.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Japan Cancer Association, 38447.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Huang T, Yao D S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5931] [Cited by in RCA: 5962] [Article Influence: 259.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Newton AC. Protein kinase C: structural and spatial regulation by phosphorylation, cofactors, and macromolecular interactions. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2353-2364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 740] [Cited by in RCA: 759] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ohno S, Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C isotypes and their specific functions: prologue. J Biochem. 2002;132:509-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:281-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 754] [Cited by in RCA: 756] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Steinberg SF. Structural basis of protein kinase C isoform function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1341-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 711] [Cited by in RCA: 679] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yoshida K. PKCdelta signaling: mechanisms of DNA damage response and apoptosis. Cell Signal. 2007;19:892-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lu W, Finnis S, Xiang C, Lee HK, Markowitz Y, Okhrimenko H, Brodie C. Tyrosine 311 is phosphorylated by c-Abl and promotes the apoptotic effect of PKCdelta in glioma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gomel R, Xiang C, Finniss S, Lee HK, Lu W, Okhrimenko H, Brodie C. The localization of protein kinase Cdelta in different subcellular sites affects its proapoptotic and antiapoptotic functions and the activation of distinct downstream signaling pathways. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:627-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamada K, Oikawa T, Kizawa R, Motohashi S, Yoshida S, Kumamoto T, Saeki C, Nakagawa C, Shimoyama Y, Aoki K, Tachibana T, Saruta M, Ono M, Yoshida K. Unconventional Secretion of PKCδ Exerts Tumorigenic Function via Stimulation of ERK1/2 Signaling in Liver Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021;81:414-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gold MG, Barford D, Komander D. Lining the pockets of kinases and phosphatases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:693-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mellor H, Parker PJ. The extended protein kinase C superfamily. Biochem J. 1998;332 (Pt 2):281-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1163] [Cited by in RCA: 1179] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Johnson JE, Giorgione J, Newton AC. The C1 and C2 domains of protein kinase C are independent membrane targeting modules, with specificity for phosphatidylserine conferred by the C1 domain. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11360-11369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nalefski EA, Falke JJ. The C2 domain calcium-binding motif: structural and functional diversity. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2375-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 609] [Cited by in RCA: 640] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Orr JW, Newton AC. Interaction of protein kinase C with phosphatidylserine. 2. Specificity and regulation. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4667-4673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ohno S, Akita Y, Konno Y, Imajoh S, Suzuki K. A novel phorbol ester receptor/protein kinase, nPKC, distantly related to the protein kinase C family. Cell. 1988;53:731-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kharait S, Dhir R, Lauffenburger D, Wells A. Protein kinase Cdelta signaling downstream of the EGF receptor mediates migration and invasiveness of prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:848-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parker PJ, Brown SJ, Calleja V, Chakravarty P, Cobbaut M, Linch M, Marshall JJT, Martini S, McDonald NQ, Soliman T, Watson L. Equivocal, explicit and emergent actions of PKC isoforms in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:51-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Newton AC. Regulation of the ABC kinases by phosphorylation: protein kinase C as a paradigm. Biochem J. 2003;370:361-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 611] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Konishi H, Yamauchi E, Taniguchi H, Yamamoto T, Matsuzaki H, Takemura Y, Ohmae K, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y. Phosphorylation sites of protein kinase C delta in H2O2-treated cells and its activation by tyrosine kinase in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6587-6592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gridling M, Ficarro SB, Breitwieser FP, Song L, Parapatics K, Colinge J, Haura EB, Marto JA, Superti-Furga G, Bennett KL, Rix U. Identification of kinase inhibitor targets in the lung cancer microenvironment by chemical and phosphoproteomics. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2751-2762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Miyamoto A, Nakayama K, Imaki H, Hirose S, Jiang Y, Abe M, Tsukiyama T, Nagahama H, Ohno S, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama KI. Increased proliferation of B cells and auto-immunity in mice lacking protein kinase Cdelta. Nature. 2002;416:865-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Basu A. Involvement of protein kinase C-delta in DNA damage-induced apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2003;7:341-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Roffey J, Rosse C, Linch M, Hibbert A, McDonald NQ, Parker PJ. Protein kinase C intervention: the state of play. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:268-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gould CM, Newton AC. The life and death of protein kinase C. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9:614-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Perletti G, Terrian DM. Distinctive cellular roles for novel protein kinase C isoenzymes. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3117-3133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Reyland ME. Protein kinase Cdelta and apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1001-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Emoto Y, Manome Y, Meinhardt G, Kisaki H, Kharbanda S, Robertson M, Ghayur T, Wong WW, Kamen R, Weichselbaum R. Proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta by an ICE-like protease in apoptotic cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:6148-6156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jackson DN, Foster DA. The enigmatic protein kinase Cdelta: complex roles in cell proliferation and survival. FASEB J. 2004;18:627-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yadav V, Yanez NC, Fenton SE, Denning MF. Loss of protein kinase C delta gene expression in human squamous cell carcinomas: a laser capture microdissection study. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1091-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Omar HA, Chou CC, Berman-Booty LD, Ma Y, Hung JH, Wang D, Kogure T, Patel T, Terracciano L, Muthusamy N, Byrd JC, Kulp SK, Chen CS. Antitumor effects of OSU-2S, a nonimmunosuppressive analogue of FTY720, in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;53:1943-1958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nambotin SB, Lefrancois L, Sainsily X, Berthillon P, Kim M, Wands JR, Chevallier M, Jalinot P, Scoazec JY, Trepo C, Zoulim F, Merle P. Pharmacological inhibition of Frizzled-7 displays anti-tumor properties in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2011;54:288-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tong M, Che N, Zhou L, Luk ST, Kau PW, Chai S, Ngan ES, Lo CM, Man K, Ding J, Lee TK, Ma S. Efficacy of annexin A3 blockade in sensitizing hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib and regorafenib. J Hepatol. 2018;69:826-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wang Q, Wang X, Evers BM. Induction of cIAP-2 in human colon cancer cells through PKC delta/NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51091-51099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mandal JP, Shiue CN, Chen YC, Lee MC, Yang HH, Chang HH, Hu CT, Liao PC, Hui LC, You RI, Wu WS. PKCδ mediates mitochondrial ROS generation and oxidation of HSP60 to relieve RKIP inhibition on MAPK pathway for HCC progression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;163:69-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Cao M, Gao J, Zhou H, Huang J, You A, Guo Z, Fang F, Zhang W, Song T, Zhang T. HIF-2α regulates CDCP1 to promote PKCδ-mediated migration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:1651-1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Takai S, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Tokuda H, Yasuda E, Toyoda H, Kaneoka Y, Yamaguchi A, Kumada T, Kozawa O. Protein kinase C delta regulates the phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Life Sci. 2007;81:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | McKiernan E, O'Brien K, Grebenchtchikov N, Geurts-Moespot A, Sieuwerts AM, Martens JW, Magdolen V, Evoy D, McDermott E, Crown J, Sweep FC, Duffy MJ. Protein kinase Cdelta expression in breast cancer as measured by real-time PCR, western blotting and ELISA. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1644-1650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | McCracken MA, Miraglia LJ, McKay RA, Strobl JS. Protein kinase C delta is a prosurvival factor in human breast tumor cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:273-281. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Savoia P, Fava P, Osella-Abate S, Nardò T, Comessatti A, Quaglino P, Bernengo MG. Melanoma of unknown primary site: a 33-year experience at the Turin Melanoma Centre. Melanoma Res. 2010;20:227-232. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Xia S, Chen Z, Forman LW, Faller DV. PKCdelta survival signaling in cells containing an activated p21Ras protein requires PDK1. Cell Signal. 2009;21:502-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | He P, Shen N, Gao G, Jiang X, Sun H, Zhou D, Xu N, Nong L, Ren K. Periodic Mechanical Stress Activates PKCδ-Dependent EGFR Mitogenic Signals in Rat Chondrocytes via PI3K-Akt and ERK1/2. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:1281-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Yan D, Chen D, Im HJ. Fibroblast growth factor-2 promotes catabolism via FGFR1-Ras-Raf-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 axis that coordinates with the PKCδ pathway in human articular chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:2856-2865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Mauro LV, Grossoni VC, Urtreger AJ, Yang C, Colombo LL, Morandi A, Pallotta MG, Kazanietz MG, Bal de Kier Joffé ED, Puricelli LL. PKC Delta (PKCdelta) promotes tumoral progression of human ductal pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2010;39:e31-e41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Huynh DTN, Baek N, Sim S, Myung CS, Heo KS. Minor Ginsenoside Rg2 and Rh1 Attenuates LPS-Induced Acute Liver and Kidney Damages via Downregulating Activation of TLR4-STAT1 and Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Macrophages. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Renu K, Saravanan A, Elangovan A, Ramesh S, Annamalai S, Namachivayam A, Abel P, Madhyastha H, Madhyastha R, Maruyama M, Balachandar V, Valsala Gopalakrishnan A. An appraisal on molecular and biochemical signalling cascades during arsenic-induced hepatotoxicity. Life Sci. 2020;260:118438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Dzierlenga AL, Cherrington NJ. Misregulation of membrane trafficking processes in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2018;32:e22035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Yang M, Chen Z, Xiang S, Xia F, Tang W, Yao X, Zhou B. Hugan Qingzhi medication ameliorates free fatty acid-induced L02 hepatocyte endoplasmic reticulum stress by regulating the activation of PKC-δ. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20:377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Koh EH, Yoon JE, Ko MS, Leem J, Yun JY, Hong CH, Cho YK, Lee SE, Jang JE, Baek JY, Yoo HJ, Kim SJ, Sung CO, Lim JS, Jeong WI, Back SH, Baek IJ, Torres S, Solsona-Vilarrasa E, Conde de la Rosa L, Garcia-Ruiz C, Feldstein AE, Fernandez-Checa JC, Lee KU. Sphingomyelin synthase 1 mediates hepatocyte pyroptosis to trigger non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2021;70:1954-1964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lee SJ, Kim SJ, Lee HS, Kwon OS. PKCδ Mediates NF-κB Inflammatory Response and Downregulates SIRT1 Expression in Liver Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ghayur T, Hugunin M, Talanian RV, Ratnofsky S, Quinlan C, Emoto Y, Pandey P, Datta R, Huang Y, Kharbanda S, Allen H, Kamen R, Wong W, Kufe D. Proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta by an ICE/CED 3-like protease induces characteristics of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2399-2404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | DeVries TA, Neville MC, Reyland ME. Nuclear import of PKCdelta is required for apoptosis: identification of a novel nuclear import sequence. EMBO J. 2002;21:6050-6060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Yoshida K. Nuclear trafficking of pro-apoptotic kinases in response to DNA damage. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:305-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Cross T, Griffiths G, Deacon E, Sallis R, Gough M, Watters D, Lord JM. PKC-delta is an apoptotic lamin kinase. Oncogene. 2000;19:2331-2337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Gao FH, Wu YL, Zhao M, Liu CX, Wang LS, Chen GQ. Protein kinase C-delta mediates down-regulation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K protein: involvement in apoptosis induction. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:3250-3258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Yamaguchi T, Miki Y, Yoshida K. Protein kinase C delta activates IkappaB-kinase alpha to induce the p53 tumor suppressor in response to oxidative stress. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2088-2097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lane DP. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature. 1992;358:15-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3502] [Cited by in RCA: 3564] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Reinhardt HC, Schumacher B. The p53 network: cellular and systemic DNA damage responses in aging and cancer. Trends Genet. 2012;28:128-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Liu H, Lu ZG, Miki Y, Yoshida K. Protein kinase C delta induces transcription of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene by controlling death-promoting factor Btf in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8480-8491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Lu ZG, Liu H, Yamaguchi T, Miki Y, Yoshida K. Protein kinase Cdelta activates RelA/p65 and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling in response to tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5927-5935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zhang J, Liu N, Zhang J, Liu S, Liu Y, Zheng D. PKCdelta protects human breast tumor MCF-7 cells against tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 2005;96:522-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Yamada K, Yoshida K. Mechanical insights into the regulation of programmed cell death by p53 via mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2019;1866:839-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Owens TW, Valentijn AJ, Upton JP, Keeble J, Zhang L, Lindsay J, Zouq NK, Gilmore AP. Apoptosis commitment and activation of mitochondrial Bax during anoikis is regulated by p38MAPK. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1551-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Chen JL, Lin HH, Kim KJ, Lin A, Ou JH, Ann DK. PKC delta signaling: a dual role in regulating hypoxic stress-induced autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy. 2009;5:244-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Wesche J, Małecki J, Wiedłocha A, Ehsani M, Marcinkowska E, Nilsen T, Olsnes S. Two nuclear localization signals required for transport from the cytosol to the nucleus of externally added FGF-1 translocated into cells. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6071-6080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Chiodelli P, Bugatti A, Urbinati C, Rusnati M. Heparin/Heparan sulfate proteoglycans glycomic interactome in angiogenesis: biological implications and therapeutical use. Molecules. 2015;20:6342-6388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Lin X. Functions of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cell signaling during development. Development. 2004;131:6009-6021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 503] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Matsuo I, Kimura-Yoshida C. Extracellular modulation of Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling through heparan sulfate proteoglycans in mammalian development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:399-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Miyamoto Y, Yamada K, Yoneda Y. Importin α: a key molecule in nuclear transport and non-transport functions. J Biochem. 2016;160:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Yamada K, Miyamoto Y, Tsujii A, Moriyama T, Ikuno Y, Shiromizu T, Serada S, Fujimoto M, Tomonaga T, Naka T, Yoneda Y, Oka M. Cell surface localization of importin α1/KPNA2 affects cancer cell proliferation by regulating FGF1 signalling. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Yang L, Fujimoto M, Murota H, Serada S, Honda H, Yamada K, Suzuki K, Nishikawa A, Hosono Y, Yoneda Y, Takehara K, Imura Y, Mimori T, Takeuchi T, Katayama I, Naka T. Proteomic identification of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K as a novel cold-associated autoantigen in patients with secondary Raynaud's phenomenon. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:349-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Ghouri YA, Mian I, Rowe JH. Review of hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, etiology, and carcinogenesis. J Carcinog. 2017;16:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 532] [Article Influence: 66.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Cheng W, Huang PC, Chao HM, Jeng YM, Hsu HC, Pan HW, Hwu WL, Lee YM. Glypican-3 induces oncogenicity by preventing IGF-1R degradation, a process that can be blocked by Grb10. Oncotarget. 2017;8:80429-80442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Cheng W, Tseng CJ, Lin TT, Cheng I, Pan HW, Hsu HC, Lee YM. Glypican-3-mediated oncogenesis involves the Insulin-like growth factor-signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1319-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Nickel W, Rabouille C. Mechanisms of regulated unconventional protein secretion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:148-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Giuliani F, Grieve A, Rabouille C. Unconventional secretion: a stress on GRASP. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:498-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Gardella S, Andrei C, Ferrera D, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Bianchi ME, Rubartelli A. The nuclear protein HMGB1 is secreted by monocytes via a non-classical, vesicle-mediated secretory pathway. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:995-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 682] [Cited by in RCA: 741] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Man SM, Karki R, Kanneganti TD. Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis, inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes in infectious diseases. Immunol Rev. 2017;277:61-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1103] [Cited by in RCA: 1223] [Article Influence: 152.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Rabouille C. Pathways of Unconventional Protein Secretion. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:230-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Kimura T, Jain A, Choi SW, Mandell MA, Johansen T, Deretic V. TRIM-directed selective autophagy regulates immune activation. Autophagy. 2017;13:989-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Zhang M, Kenny SJ, Ge L, Xu K, Schekman R. Translocation of interleukin-1β into a vesicle intermediate in autophagy-mediated secretion. Elife. 2015;4:e11205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Andrei C, Dazzi C, Lotti L, Torrisi MR, Chimini G, Rubartelli A. The secretory route of the leaderless protein interleukin 1beta involves exocytosis of endolysosome-related vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1463-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Frye BC, Halfter S, Djudjaj S, Muehlenberg P, Weber S, Raffetseder U, En-Nia A, Knott H, Baron JM, Dooley S, Bernhagen J, Mertens PR. Y-box protein-1 is actively secreted through a non-classical pathway and acts as an extracellular mitogen. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:783-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Qi X, Mochly-Rosen D. The PKCdelta -Abl complex communicates ER stress to the mitochondria - an essential step in subsequent apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:804-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Kajimoto T, Ohmori S, Shirai Y, Sakai N, Saito N. Subtype-specific translocation of the delta subtype of protein kinase C and its activation by tyrosine phosphorylation induced by ceramide in HeLa cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1769-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Wang H, Xiao L, Kazanietz MG. p23/Tmp21 associates with protein kinase Cdelta (PKCdelta) and modulates its apoptotic function. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15821-15831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |