Published online Mar 7, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i9.854

Peer-review started: November 28, 2020

First decision: January 17, 2021

Revised: January 23, 2021

Accepted: February 11, 2021

Article in press: February 11, 2021

Published online: March 7, 2021

Processing time: 94 Days and 23.9 Hours

Various surgical procedures have been described for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) at the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) close to the Z-line. However, surgery for EGJ-GIST involving Z-line has been rarely reported.

To introduce a novel technique called conformal resection (CR) for open resection of EGJ-GIST involving Z-line.

In this retrospective study, 43 patients having GISTs involving Z-line were included. The perioperative outcomes of patients receiving CR (n = 18) was compared with that of proximal gastrectomy (PG) (n = 25).

CR was successfully performed in all the patients with negative microscopic margins. The mean operative time, time to first passage of flatus, and postoperative hospital stay was significantly shorter in the CR group (P < 0.05), while the intraoperative blood loss was similar in the two groups. The postoperative gastroesophageal reflux as diagnosed by esophageal 24-h pH monitoring and quality of life at 3 mo were significantly in favor of CR compared to PG (both P < 0.001). The 5-year disease-free survival between the two groups was similar (P = 0.163). The cut- off value for the determination of CR or PG was 7.0 mm above the Z-line (83.33% sensitivity, 84.00% specificity, 83.72% accuracy).

CR is safe and feasible for EGJ-GIST located within 7.0 mm above the Z-line.

Core Tip: We retrospectively enrolled 43 cases of esophagogastric junction-gastrointestinal stromal tumor (EGJ-GIST) involving Z-line, including 25 cases in the proximal gastrectomy (PG) group and 18 cases in the conformal resection (CR) group. The operation CR was introduced, and the following indicators were analyzed: Clinicopathological characteristics, perioperative outcomes, postoperative esophageal 24-h pH, postoperative quality of life, and 5-year disease-free survival. Finally, the cut-off value above the Z-line for the determination of CR or PG was determined. Our results confirm that CR is safe and feasible for EGJ-GIST located within 7.0 mm above the Z-line. CR was associated with lower incidence of postoperative gastroesophageal reflux and better quality of life with similar oncological outcomes compared to PG.

- Citation: Zheng GL, Zhang B, Wang Y, Liu Y, Zhu HT, Zhao Y, Zheng ZC. Surgical resection of esophagogastric junction stromal tumor: How to protect the cardiac function. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(9): 854-865

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i9/854.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i9.854

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) contribute to 1%-3% of all gastrointestinal malignancies. They originate primarily from the interstitial cells of Cajal or from their stem cell precursors[1]. The most common sites of GIST are the stomach and small intestine. Rarely, they can arise in the esophagus, appendix, gallbladder, pancreas, and the retroperitoneum[2]. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for localized and resectable GIST. The main principles of the surgical procedure are complete excision with tumor-free resection margins and preservation of the organ functions as much as possible[3].

The esophagogastric junction (EGJ) is an uncommon site of GIST. Surgery in such cases is often difficult due to the anatomical location of these tumors with the need to perform proximal gastrectomy (PG). Resection of the EGJ with cardia results in severe postoperative gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and poor quality of life. The main hurdle to understanding and treating these tumors is their relative rarity and the subsequent shortage of literature. Recently, many different surgical procedures have been described to resect EGJ-GIST near the Z-line called type B lesions (Figure 1)[4-10]. However, there are limited studies on resection of type A lesions (when the tumor is located at the EGJ and the upper edge of the tumor is invading the Z-line) (Figure 1). For type A GIST, surgical approach is technically challenging because of the complex anatomical factors and the difficulty of functional preservation of lower esophageal sphincter[11,12].

In this article we have described a novel technique for EGJ-GIST involving Z-line (type A) called conformal resection (CR). The main purpose of this surgical technique was to achieve R0 resection of GIST with preservation of the sphincter function. We have also compared the outcomes of CR with PG.

This study is a retrospective analysis of the prospectively maintained database of sarcoma patients at Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute. In this study, we included patients undergoing resection of primary localized EGJ-GIST involving Z-line from January 2009 to December 2017. All cases were diagnosed as GIST after preoperative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration or core needle biopsy. Patients were excluded if they underwent concomitant resection for other malignancies, e.g., patients with incidentally discovered GISTs in specimens resected for gastric, esophageal, or pancreatic carcinomas. The data of the patients collected were as follows: Clinical and pathologic findings, intra-operative and postoperative outcomes, esophageal 24-h pH parameters, the 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), and disease-free survival (DFS). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Cancer Hospital of China Medical University (Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute) (ethics number: 20190461). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient at our center. The decision to perform CR or PG was taken by the treating surgeon based on the preoperative endoscopy and intraoperative findings.

The patient was placed in the supine position. The median upper abdominal incision of 15-20 cm was taken from the xiphoid process after induction of general anesthesia. The abdominal wall was retracted by a self-retaining retractor. To facilitate subsequent dissection, the triangular ligament of the left lobe of the liver was taken down with electrocautery to expose the esophageal hiatus and the gastric cardia. We made a precise and irregular excision according to the shape of the type A GIST and preserved the Z-line as much as possible and then performed manual suturing. We used the concept of conformal radiotherapy for reference and named the operation CR. This procedure is different from previous simple wedge resection or PG.

The surgical technique of CR of the type A GIST lesions located on the anterior wall and posterior wall of EGJ has been described below.

The tumor location was confirmed by visualization and palpation (Figure 2A and B). The lesser omentum at the EGJ was separated, and the cardia was clearly exposed on the right side. According to the size and shape of the tumor, wide local excision was performed in a caudo-cranial fashion from the gastric side of the tumor along the edge of the tumor to the esophageal side of the tumor. The resected specimen included part of the anterior wall of the stomach and part of the anterior wall of the esophagus (Figure 2C). The esophageal resection margin was kept as small as possible so as to preserve the cardiac function. Esophageal margin was examined by intraoperative frozen section to ensure a negative margin. After the complete removal of the tumor, the defect was sutured with 3-0 absorbable interrupted full thickness sutures. The esophageal wall was sutured to the gastric wall beginning from the gastric greater curvature and progressed towards the lesser curvature so as to prevent the risk of cardiac stenosis (Figure 2D and E).

The tumor location on the posterior wall of EGJ was confirmed by palpation (Figure 3A). The anterior gastrotomy was made close to the EGJ of about 10 cm (Figure 3B). After entering the gastric cavity, the tumor was visualized and excised along the edge of the tumor, including the part of the posterior wall of the stomach and the left lateral wall of the esophagus (Figure 3C). The defect was sutured accordingly to the above-mentioned principles for the anterior wall tumors (Figure 3D). Finally, the anterior gastrotomy was sutured.

Follow-up of the patients was conducted by telephone or in the outpatient department. Gastroduodenal endoscopic examination was done to look for deformity or stenosis of the EGJ at 2 mo postoperatively (Figure 4). All patients received esophageal 24-h pH monitoring and SF-36 at the third month after surgery, and regular abdominal enhanced computed tomography every 3-4 mo within 2 years, and every 6 mo in 2-5 years. Medium-risk and high-risk GIST patients received imatinib targeted therapy after surgery for 1 year and 3-5 years, respectively.

Esophageal 24-h pH monitoring: Esophageal 24-h pH monitoring was measured with an antimony electrode (Medtronic Functional Diagnostics A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark). Data were digitized with a Macintosh computer (Apple Computer Inc, Cupertino, CA, United States) and the digitized signals were displayed and analyzed using AcqKnowledge software (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA, United States). The patients were advised not to consume any food or drink below pH 4 during the week before monitoring. All patients were studied after an overnight fast. The pH electrode was positioned 5 cm above the cardia. Ambulatory pH recordings were then undertaken for 24 h. Monitoring indicators included mean of 24-h pH, total time for pH < 4, number of acid reflux events in 24 h (standing, lying), and number of regurgitations (> 5 min)[13].

SF-36: The SF-36 is an extensively used generic questionnaire for the assessment of health-related quality of life (QoL), which contained eight dimensions [physical function (PF), role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role-emotional (RE), and mental health (MH)]. The score ranges from 0 to 100; the higher score indicating a better health related QoL[14].

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, United States). In this study, continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The χ2-test and Fisher exact test were applied to compare categorical data of CR and PG groups. The statistical analysis of intra-operative and postoperative correlation coefficients, the esophageal 24-h pH parameters, and the SF-36 parameters were performed by t-test. The cut-off value to discriminate surgical method was analyzed by the Youden index from the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Estimations for DFS were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between Kaplan-Meier curves were investigated by log-rank test. Statistical significance was set at P value < 0.05.

A total of 43 patients were included in this study. Eighteen patients underwent CR, and 25 patients underwent PG including gastric cardia (PG).

The clinical and pathologic variables of patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age of all patients was 59.4 years, and 24 were males. There was no significant difference in the mean age and gender between the CR and PG groups. The median tumor size in the CR and PG groups was 6.4 cm (1.8-12.5 cm) and 8.3 cm (2.5-14 cm), respectively. Most tumors were of spindle histologic subtype in both groups (13/18 in the CR and 18/25 in the PG groups), had Ki67 index ≤ 5% (15/18 in the CR and 16/25 in the PG groups), and had mitotic rate < 5/50 HPF (high-power field, 30/43 in both the CR and PG groups). Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for CD117, CD34, and DOG-1 in 38 (88.37%), 39 (90.70%), and 36 (83.72%) cases, respectively. The two groups were comparable with respect to the modified National Institutes of Health risk classification[15].

| Variables | CR group | PG group | P value |

| Age, median (range), in yr | 58 (32-73) | 61 (28-75) | 0.532 |

| Sex | 0.168 | ||

| Male | 8 | 16 | |

| Female | 10 | 9 | |

| Size in cm | 0.549 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2.1-5.0 | 6 | 6 | |

| 5.1-10 | 7 | 13 | |

| > 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Histologic type | 0.71 | ||

| Spindle | 13 | 18 | |

| Epitheloid | 1 | 3 | |

| Mixed | 4 | 4 | |

| Mitotic index, per 50 HPF | 0.766 | ||

| ≤ 5 | 13 | 17 | |

| > 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| Ki-67 | 0.163 | ||

| ≤ 5% | 15 | 16 | |

| > 5% | 3 | 9 | |

| CD117 | 0.929 | ||

| Positive | 16 | 22 | |

| Negative | 2 | 3 | |

| CD34 | 0.159 | ||

| Positive | 15 | 24 | |

| Negative | 3 | 1 | |

| DOG-1 | 0.083 | ||

| Positive | 13 | 23 | |

| Negative | 5 | 2 | |

| NIH risk category | 0.476 | ||

| Very low risk | 1 | 0 | |

| Low risk | 5 | 4 | |

| Intermediate risk | 7 | 12 | |

| High risk | 5 | 9 | |

| Length of the upper edge of the GIST crossing the Z-line, mean ± SD (cm) | 0.639 (0.29) | 1.024 (0.395) | 0.193 |

| Circumference of the EGJ involvement | 0.716 | ||

| T ≤ 1/4 | 10 | 13 | |

| 1/4 < T ≤ 2/4 | 7 | 8 | |

| 2/4 < T ≤ 3/4 | 1 | 3 | |

| T > 3/4 | 0 | 1 | |

| Heartburn, postoperative | |||

| Yes | 3 | 16 | 0.004 |

| No | 15 | 9 | |

| Oral antacids, postoperative | |||

| Yes | 4 | 18 | 0.002 |

| No | 14 | 7 |

Table 2 compares the intra-operative and postoperative outcomes of the two surgical procedures for type A GISTs. The results showed that except for intraoperative blood loss (59.44 ± 23.08 vs 90.60 ± 35.62, P = 0.069), the other indicators were significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.05), suggesting that CR group was significantly superior to the PG group. The negative rate of surgical margin was 100% in both groups.

| CR group, n = 18 | PG group, n = 25 | P value | 95%CI | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Operating time in min | 108.61 ± 30.13 | 137.80 ± 51.04 | 0.029 | -56.41 | -0.97 |

| Intraoperative blood loss in mL | 59.44 ± 23.08 | 90.60 ± 35.62 | 0.069 | -53.53 | -11.78 |

| First passage of flatus time in h | 29.11 ± 15.35 | 74.24 ± 40.39 | 0.013 | -65.389 | -24.87 |

| Days to oral intake | 3.56 ± 1.65 | 8.68 ± 3.88 | 0.006 | -7.09 | -3.16 |

| Postoperative hospital stay in d | 6.00 ± 2.40 | 10.96 ± 4.15 | 0.049 | -7.17 | -2.75 |

| Negative margin, % | 100 | 100 | |||

Table 3 summarizes the postoperative esophageal 24-h pH parameters such as the mean 24-h pH, total time for pH < 4, acid reflux number of 24 h, and regurgitation times (> 5 min) after both surgical procedures for type A GISTs. The results of the two groups were compared, and it was found that the postoperative reflux of CR group was significantly less than that of PG group (all P < 0.001).

| Mean 24-h pH | Total time for pH < 4 (min) | Acid reflux number of 24 h | Regurgitation events, > 5 min | ||

| Standing | Lying | ||||

| CR group, n = 18 | 4.97 ± 1.44 | 31.83 ± 22.65 | 17.83 ± 11.25 | 35.62 ± 15.71 | 1.44 ± 1.68 |

| PG group, n = 25 | 3.41 ± 1.15 | 184.48 ± 118.74 | 32.68 ± 15.89 | 58.81 ± 19.13 | 6.04 ± 1.92 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

On comparison of the postoperative health-related quality of life, it was found that CR group had higher PF, RP, BP, GH, VT, SF, RE, and MH scores compared with PG group (all P < 0.01) (Table 4).

| PF | RP | BP | GH | VT | SF | RE | MH | |

| CR group, n = 18 | 53.72 ± 2.13 | 54.61 ± 1.61 | 60.94 ± 1.86 | 61.56 ± 1.75 | 61.72 ± 3.49 | 55.11 ± 2.24 | 50.61 ± 2.93 | 55.00 ± 2.27 |

| PG group, n = 25 | 48.00 ± 3.64 | 48.36 ± 2.89 | 49.80 ± 4.12 | 50.72 ± 5.15 | 52.20 ± 4.06 | 44.60 ± 2.63 | 37.16 ± 4.08 | 46.12 ± 3.95 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

We generated ROC curves to find best the Youden index to detect the cut-off value for predicting the surgical method. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.907, indicating that the cut-off value of the length of the upper edge of the GIST crossing the Z-line (or invading the esophagus) was 7.0 mm. It can also be understood that when the invasion of the esophagus is greater than 0.7 cm, it is not suitable for CR. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy rates were 83.33%, 84.00%, 78.90%, 87.51%, and 83.72%, respectively (Figure 5).

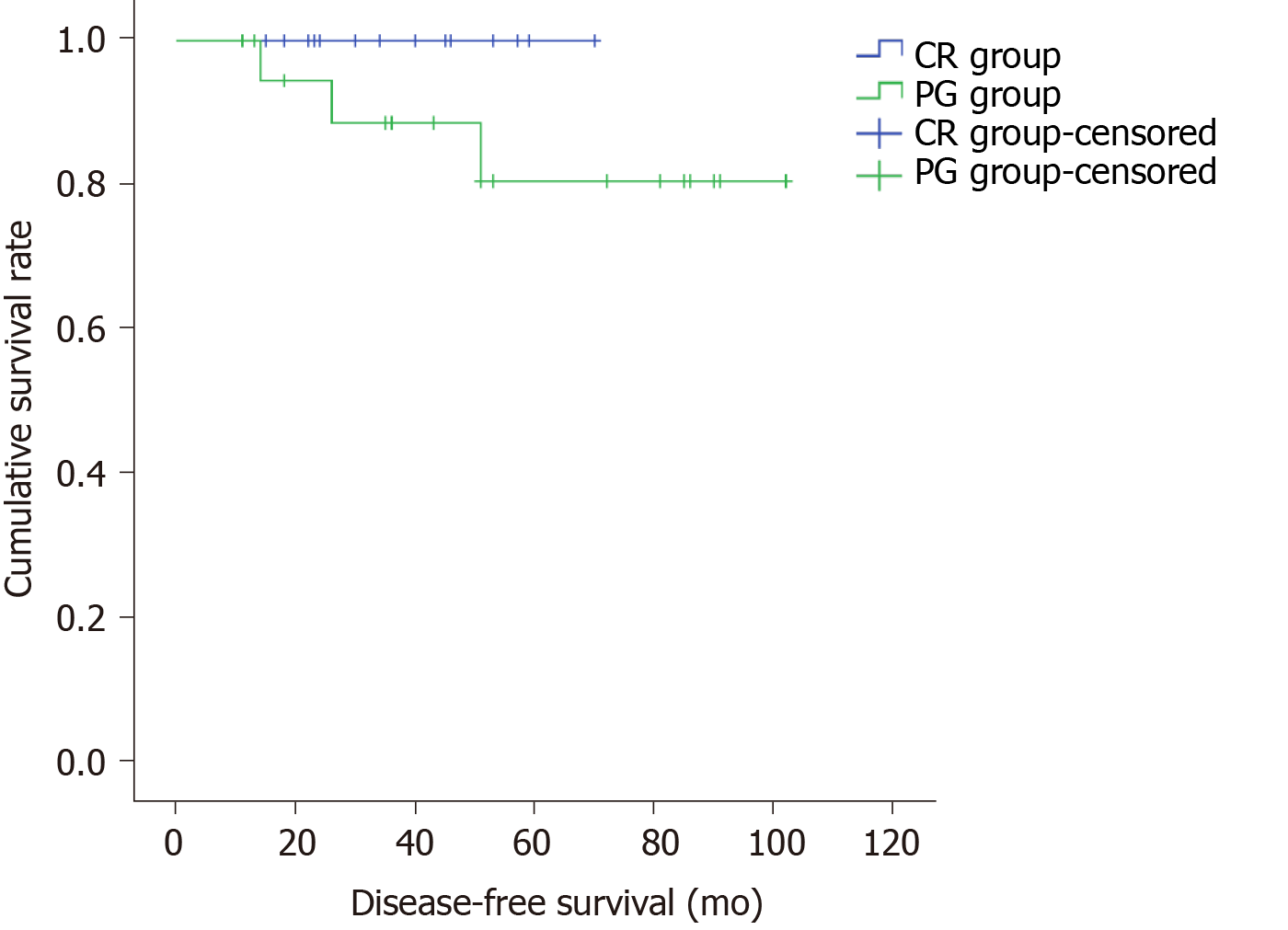

A total of 37 patients were included for the analysis of DFS (CR group: 17, PG group: 20) after excluding one case of preoperative liver metastasis from the CR group and 3, 1, and 1 case of liver metastasis, peritoneal metastasis, and diaphragm invasion from the PG group, respectively. Median follow up was 46.2 mo (range, 11-102 mo). The 5-year DFS was 100% in the CR group and 85% in the PG group, and the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.163, Figure 6).

In this study, we described a novel surgical technique of CR for type A EGJ-GIST in order to retain the gastric cardia function as much as possible and prevent postoperative GER. We found that the perioperative outcomes of CR were superior to PG including 24-h pH monitoring and SF-36. The results showed that CR was safe and feasible.

PG has been the only recommended operation in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines[3] and related studies on EGJ-GIST[8,16]. PG is associated, however, with high risk of postoperative GER. The incidence of reflux esophagitis after PG is high and usually accompanied by symptoms such as acid reflux and retrosternal burning[17]. Besides, GER seriously affects the quality of life of patients and requires them to take drugs such as omeprazole for a long time. In the present study, the symptoms of heartburn (3/18 vs 16/25, P < 0.05) and need for acid-suppressive drugs (4 /18 vs 18/25, P < 0.05) were significantly less in the CR group compared to the PG group suggesting that CR was significantly superior to the traditional PG in controlling GER.

The gold standard for evaluating GER is 24-h pH monitoring[18]. It objectively measures the change of pH value in the esophagus under physiological state. pH < 4 total time percentage and the number of consecutive > 5 min are the main parameters used to diagnose and assess the severity of acid reflux[13]. In the current study, the CR group was significantly superior to the PG group based on the 24-h pH study findings including the mean 24-h pH, total time for pH < 4, acid reflux number of 24 h (standing), acid reflux number of 24 h (lying), and regurgitation times (> 5 min). These findings provide objective evidence for the reduction in GER by CR.

Impairments of health-related QoL in patients with heartburn have been reported previously[14,19]. We adopted the SF-36 questionnaire, which is an extensively used generic questionnaire for assessing physical and mental related QoL[14]. We found that the patients in PG group displayed a much poorer QoL (both mental and physical) in comparison with those in CR group. This difference might be partly because of the high incidence of heartburn in PG group, which contributed to the high levels of psychological burden[20].

CR was performed according to the shape of the tumor and the extent of invasion of the cardiac muscle, so as to minimize the damage to the anatomical structure of the gastric cardia. In our experience, we found that the distance of the tumor across the Z-line was the key determinant of whether CR can be performed. The cut-off value calculated by ROC curve was 7.0 mm, which was the maximum adaptive distance of CR. If it exceeds 7.0 mm, then it will inevitably result in excessive resection of esophageal tissue, which is not suitable for this operation. Also, if the tumor is involving the EGJ circumferentially, then CR is not possible. However, none of the patients in our study had circumferentially involvement of the EGJ by the tumor. At the same time, it is important to limit the resection of esophagus and cardiac muscles as much as possible by using intraoperative frozen section and preserve the cardiac function to the maximum extent. With this technique we achieved negative margins in all the cases operated in this study. Another important aspect of CR is the suturing of the defect after resection. In order to prevent stenosis, we sutured the esophageal wall to the gastric wall and not to the esophageal wall. All these goals of CR can be best achieved by open surgery. Laparoscopic resection and suturing for CR can be technically very challenging. Previous studies have shown that the ratio of conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy was high for EGJ-GIST that did not involve Z-line[21-23]. Laparoscopic surgery has not been recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines[3]. Future studies by experienced laparoscopic surgeons will help to determine whether CR can be safely performed by laparoscopy.

In this study, the operative time, time for first passage of flatus, and postoperative hospital stay were significantly less in the CR group suggesting that the CR group induced less surgical damage and faster recovery of patients. Moreover, the long-term outcomes such as DFS was similar between CR and PG, indicating that CR helped in preserving gastric cardiac function without compromising the oncological outcomes.

There are some limitations of this study. First, it was a retrospective study with potential for selection bias. Second, the sample size of this study was small. Third, this study was a single center study. Future larger prospective multicenter studies are needed to validate the findings of this study.

CR is a safe and feasible alternative to PG for non-circumferential localized EGJ-GIST within 7.0 mm above the Z-line. CR is associated with lower risk of postoperative GER and better quality of life compared to PG.

For gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) at the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) involving the Z-line, previous proximal gastrectomy (PG) results in serious postoperative reflux and poor quality of life.

To explore and improve the surgical methods of GIST in this part, so as to preserve the cardiac sphincter as much as possible and reduce the incidence of postoperative reflux esophagitis.

We aimed to describe a novel technique to achieve R0 resection of EGJ-GIST involving Z-line with preservation of the sphincter function. We have also compared the outcomes of conformal resection with PG.

In this study, 43 patients having GISTs involving Z-line were included. The perioperative outcomes of patients receiving conformal resection (CR) (n = 18) was compared with that of PG (n = 25). The data of the patients collected were as follows: Clinical and pathologic findings, intra-operative and postoperative outcomes, esophageal 24-h pH parameters, the 36-item short-form health survey, and disease-free survival.

CR was successfully performed in all the patients with negative microscopic margins. The mean operative time, time to first passage of flatus, and postoperative hospital stay was significantly shorter in CR group (P < 0.05), while the intraoperative blood loss was similar in the two groups. The postoperative gastroesophageal reflux as diagnosed by esophageal 24-h pH monitoring and quality of life at 3 mo were significantly in favor of CR compared to PG (both P < 0.001). The 5-year disease-free survival between the two groups were similar (P = 0.163). The cut- off value for the determination of CR or PG was 7.0 mm above the Z-line (83.33% sensitivity, 84.00% specificity, 83.72% accuracy).

CR is safe and feasible for EGJ-GIST located within 7.0 mm above the Z-line. CR was associated with lower incidence of postoperative GER and better quality of life with similar oncological outcomes compared to PG.

Our surgical team will continue to conduct survival follow-up for enrolled patients and cooperate with multiple centers to explore further the advantages and disadvantages of this surgical approach.

We wish to thank Yu HH for help with statistics.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cho JY S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, Meis-Kindblom JM. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1259-1269. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Medeiros F, Corless CL, Duensing A, Hornick JL, Oliveira AM, Heinrich MC, Fletcher JA, Fletcher CD. KIT-negative gastrointestinal stromal tumors: proof of concept and therapeutic implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:889-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, Kane JM, Keedy V, Kim E, Koon H, Mayerson J, McCarter M, McGarry SV, Meyer C, Morris ZS, O'Donnell RJ, Pappo AS, Paz IB, Petersen IA, Pfeifer JD, Riedel RF, Ruo B, Schuetze S, Tap WD, Wayne JD, Bergman MA, Scavone JL. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:536-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 76.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Privette A, McCahill L, Borrazzo E, Single RM, Zubarik R. Laparoscopic approaches to resection of suspected gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on tumor location. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:487-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Nguyen NT, Shapiro C, Massomi H, Laugenour K, Elliott C, Stamos MJ. Laparoscopic enucleation or wedge resection of benign gastric pathology: analysis of 44 consecutive cases. Am Surg. 2011;77:1390-1394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hara J, Nakajima K, Takahashi T, Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Kurokawa Y, Takiguchi S, Mori M, Doki Y. Laparoscopic intragastric surgery revisited: its role for submucosal tumors adjacent to the esophagogastric junction. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:251-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Conrad C, Nedelcu M, Ogiso S, Aloia TA, Vauthey JN, Gayet B. Laparoscopic intragastric surgery for early gastric cancer and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xiong W, Zhu J, Zheng Y, Luo L, He Y, Li H, Diao D, Zou L, Wan J, Wang W. Laparoscopic resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors in esophagogastric junction (EGJ): how to protect the EGJ. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:983-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xu X, Chen K, Zhou W, Zhang R, Wang J, Wu D, Mou Y. Laparoscopic transgastric resection of gastric submucosal tumors located near the esophagogastric junction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1570-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Lyu Z, Yang Z, Wang J, Hu W, Li Y. Totally Laparoscopic Transluminal Resection for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Located at the Cardiac Region. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:2218-2219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Coccolini F, Catena F, Ansaloni L, Lazzareschi D, Pinna AD. Esophagogastric junction gastrointestinal stromal tumor: resection vs enucleation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4374-4376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Peparini N, Carbotta G, Chirletti P. Enucleation for gastrointestinal stromal tumors at the esophagogastric junction: is this an adequate solution? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2159-2160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adhami T, Richter JE. Twenty-four hour pH monitoring in the assessment of esophageal function. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;13:241-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ortiz-Garrido O, Ortiz-Olvera NX, González-Martínez M, Morán-Villota S, Vargas-López G, Dehesa-Violante M, Ruiz-de León A. Clinical assessment and health-related quality of life in patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2015;80:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 866] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ke CW, Cai JL, Chen DL, Zheng CZ. Extraluminal laparoscopic wedge resection of gastric submucosal tumors: a retrospective review of 84 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1962-1968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hao LL, Lei M, Lai XY, Zheng MW, Yang L. Clinical observation of digestive tract reconstruction in the treatment of gastric proximal gastrectomy. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2011;91:961-964. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Ahmad M. Omeprazole test and 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring in diagnosing GERD. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1012-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee SW, Lien HC, Lee TY, Yang SS, Yeh HJ, Chang CS. Heartburn and regurgitation have different impacts on life quality of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12277-12282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Heidelbaugh JJ, Gill AS, Van Harrison R, Nostrant TT. Atypical presentations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:483-488. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Amin AT, Kono Y, Shiraishi N, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Kitano S. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic wedge resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach of less than 5 cm in diameter. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:260-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Karakousis GC, Singer S, Zheng J, Gonen M, Coit D, DeMatteo RP, Strong VE. Laparoscopic versus open gastric resections for primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a size-matched comparison. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1599-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Poškus E, Petrik P, Petrik E, Lipnickas V, Stanaitis J, Strupas K. Surgical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a single center experience. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2014;9:71-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |