Published online Jun 14, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i22.3109

Peer-review started: March 5, 2021

First decision: March 27, 2021

Revised: April 11, 2021

Accepted: May 22, 2021

Article in press: May 22, 2021

Published online: June 14, 2021

Processing time: 94 Days and 17.2 Hours

Oral tacrolimus is a therapeutic agent for moderate to severe steroid-dependent or resistant ulcerative colitis (UC), but remission induction is difficult, and it is necessary to treat the patient while considering the next treatment.

To examine serum albumin (Alb) level as a prognostic factor for the therapeutic effect of tacrolimus in clinical practice.

Forty-seven patients with UC treated with tacrolimus at our institution were divided into remission and failure groups (colectomy or switch to biologics), and the biological data at the start of observation and at weeks 1 and 2 were retrospectively examined. Kaplan-Meier and multivariate analyses were performed using Alb as a prognostic factor in UC treatment.

During the three months observed, 17 (36.2%) patients failed treatment with tacrolimus. A comparison between the failure and remission groups showed a significant difference only in Alb in week 2, and in the week 2/week 0 Alb ratio, which showed the rate of change in Alb. The cut-off value of the week 2/week 0 Alb ratio that predicted failure was 1, and its area under the curve was 0.751 (95%CI: 0.604-0.898). In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, a week 2/week 0 Alb ratio ≤ 1 had a significantly higher failure rate than that of > 1; Cox proportional hazard regression analysis also showed that a week 2/week 0 Alb ratio ≤ 1 was an independent prognostic factor for failure within 3 mo after the start of tacrolimus treatment.

A week 2/week 0 Alb ratio ≤ 1 predicts failure within 3 mo of tacrolimus administration for UC. High failure risk exists with week 2 Alb values ≤ 1 on admission.

Core Tip: The usefulness of serum albumin as a predictor of the therapeutic effect of oral tacrolimus for ulcerative colitis was investigated. Lower albumin levels in week 2 than in week 0 after achieving trough levels of tacrolimus were shown to increase risk for failure, including colectomy and switch to biologics, within 3 mo. In these cases, changes to other treatment options, including surgical total colectomy, should be considered as soon as possible.

- Citation: Ishida N, Miyazu T, Tamura S, Tani S, Yamade M, Iwaizumi M, Hamaya Y, Osawa S, Furuta T, Sugimoto K. Early serum albumin changes in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with tacrolimus will predict clinical outcome. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(22): 3109-3120

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i22/3109.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i22.3109

The incidence of ulcerative colitis (UC) is increasing worldwide[1]. Although corticosteroid treatment is the highest priority treatment option for patients with moderate to severe UC, there are patients with steroid dependence or resistance, and approximately 20%-30% of them do not improve following steroid treatment[2,3]. Although therapeutic agents such as biologics and calcineurin inhibitors are used as medical treatments to replace steroids, if none of these advanced treatments are successful, colectomy must be performed for these patients.

Treatment with oral tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, has been reported to be effective in patients with steroid-dependent and steroid-resistant UC[4,5]. Recently, in addition to studies on short-term results of tacrolimus for UC, studies on medium-to-long-term treatment results have also been reported[6-9]. Although the efficacy of tacrolimus has been demonstrated in these reports, there are patients who have failed to respond to this treatment and are forced to switch to other treatments, such as biologic therapy and colectomy. Continuing refractory treatment unnecessarily prolongs hospital stay and increases the risk of immunosuppressive and perioperative complications due to poor nutritional status[10,11]. When oral tacrolimus initially became available as a therapeutic agent for UC, only anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α antibody agents were indicated for UC as biologics; however, various advanced treatments, including small-molecule Janus kinase inhibitors, anti-interleukin 12/23 antibodies, and anti-integrin antibodies are now available[12-14]. This means that we now have many alternative treatment options for tacrolimus refractory cases. Hence, the decision to switch to another treatment must be made as soon as possible and accurately in refractory cases.

Several studies have validated the therapeutic response to tacrolimus in UC. Nishida et al[15] proved that the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio was an independent prognostic factor after the induction of tacrolimus therapy. Ban et al[16] reported that the factors predicting colectomy after the induction of calcineurin inhibitor were cytomegalovirus antigenemia (C7HRP) positivity, a cumulative prednisolone dose of 10000 mg or more before the start of treatment, and a combination of hematocrit and the Onodera-prognostic nutritional index[16]. This study also demonstrated that the serum albumin (Alb) level before the induction of tacrolimus was useful as a predictor of early colectomy. Further, Herrlinger et al[17] reported that ABCB1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms predict the therapeutic response to tacrolimus.

In this study, we retrospectively examined the clinical course after the induction of remission by tacrolimus and the factors involved in its clinical outcome. As a prognostic factor that can be easily measured in clinical practice, changes in serum Alb levels before and after the induction of remission with tacrolimus were evaluated.

Patients with UC who were treated with tacrolimus and had a medical record at the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine between August 2010 and January 2020 were enrolled in this study. The diagnosis of UC was made based on typical medical history and clinical features, as well as endoscopic and histological evaluation, in line with recent guidelines. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who were not diagnosed with UC, such as indeterminate colitis or unclassified IBD, were excluded. Patients were diagnosed with moderate to severe UC based on clinical activity index, biological data, and endoscopic findings.

This was a retrospective observational study conducted in a single center. The purpose of this study was to identify prognostic factors that may lead to clinical failure in patients with UC treated with tacrolimus. The primary outcome measure of this study was clinical failure in which a switch to colectomy or biologics was performed within 3 mo after tacrolimus induction. Secondary endpoints were comparison of biological data and clinical findings between the remission and failure groups.

Enrolled patients were evaluated for clinical disease activity using the Rachmilewitz index[18]. The values of serum C-reactive protein (CRP), Alb, hemoglobin (Hb), and white blood cell (WBC) count and differential were measured in our facility on admission and more than twice per week.

Colonoscopy was performed on all enrolled patients before tacrolimus induction. UC mucosal status was assessed using the Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES)[19]. MES was assessed according to the following criteria: 0, normal or inactive disease; 1, mild disease with erythema, decreased vascular pattern, mild friability; 2, moderate disease with marked erythema, absence of vascular patterns, friability, and erosions; and 3, severe disease with spontaneous bleeding and ulceration. Mucosal healing was defined as MES 0 or 1.

The initial tacrolimus dose was started at 0.05 mg/kg twice daily. The blood trough levels of tacrolimus were measured 2 to 3 times a week, and tacrolimus doses were adjusted. The dose of tacrolimus was increased until a high trough level of 10-15 mg/mL was achieved. In this study, we defined day 1 as the day when a high trough level was reached after the start of oral tacrolimus administration. Oral administration of tacrolimus at a dose capable of maintaining a high trough level was continued for 2 wk, and then the dose was reduced to a low trough level (5-10 ng/mL). In this study, patients who underwent colectomy or switched to biologics within 3 mo after day 1 were defined as having clinical failure.

Statistical analyses of the data were performed using SPSS version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) software. Differences between median values were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted to determine the optimal Alb cut-off value (week 2/week 0) for predicting failure within 3 mo. The accuracy of the predicted failure ratio was evaluated using the area under the ROC curve. The cumulative remission rate was analyzed using Cox proportional hazard regression and Kaplan-Meier analysis, and was compared using the log-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

This retrospective study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (number 20-356). This study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice principles in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki.

The characteristics of forty-seven UC patients enrolled in this study are shown in Table 1. The mean patient age was 44.9 years, and the mean disease duration was 3.2 years. Patients with extensive colitis and left sided colitis numbered 42 and 5, respectively. On colonoscopy, 38 patients (80.9%) had MES 3, and nine patients (19.1%) had MES 2. Twelve patients (25.5%) had a history of treatment with biologics. The mean time to high-level trough with tacrolimus was 8.1 d.

| Characteristics | n = 47 |

| Age (yr), mean (range) ± SD | 44.9 (16-78) ± 18.7 |

| Male/female, n (%) | 38/9 (80.9/10.6) |

| Disease duration (yr), mean (range) ± SD | 3.2 (0.1-42) ± 7.0 |

| Disease extent, n (%) | |

| Extensive colitis | 42 (89.4) |

| Left sided colitis | 5 (10.6) |

| CAI (Rachmilewitz index) mean (range) ± SD | 11.0 (7-17) ± 2.7 |

| MES | |

| MES 2 | 9 (19.1) |

| MES 3 | 38 (80.9) |

| Medication at study, n (%) | |

| Oral 5-ASA | 21 (44.7) |

| Suppository 5-ASA | 7 (14.9) |

| Systemic steroids | 28 (59.6) |

| Immunomodulators | 10 (21.3) |

| Biologics | 11 (23.4) |

| History of biologics, n (%) | 12 (25.5) |

| Time to high trough level (d), mean (range) ± SD | 8.1 (0-46) ± 7.5 |

During the 3-mo follow-up from the start of the study, 17 of 47 patients (36.2%) experienced clinical failure. On comparison of the remission and failure groups, as shown in Table 2, the failure group was older and tended to have a longer disease duration than the remission group, but this finding was not statistically significant. In addition, a history of treatment with biologics did not show a significant difference between the two groups.

| Characteristics | Remission (n = 30) | Failure (n = 17) | P value |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 41.33 ± 16.8 | 51.1 ± 20.7 | 0.084 |

| Male/female, n (%) | 23/7 (76.7 / 23.3) | 15/2 (88.2/11.8) | 0.455 |

| Disease duration (yr), mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 2.8 | 5.46 ± 10.9 | 0.098 |

| Disease extent, n (%) | |||

| Extensive colitis | 27 (90.0) | 15 (88.2) | 1 |

| Left sided colitis | 3 (10.0) | 2 (11.8) | |

| CAI (Rachmilewitz index), mean ± SD | 10.7 ± 2.4 | 11.7 ± 2.9 | 0.221 |

| MES | |||

| MES 2 | 6 (20.0) | 3 (17.6) | 1 |

| MES 3 | 24 (80.0) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Medication at study, n (%) | |||

| Oral 5-ASA | 16 (53.3) | 5 (29.4) | 0.138 |

| Suppository 5-ASA | 5 (16.7) | 2 (11.8) | 1 |

| Systemic steroids | 19 (63.3) | 9 (52.9) | 0.546 |

| Immunomodulators | 6 (20.0) | 4 (23.5) | 1 |

| Biologics | 6 (20.0) | 5 (29.4) | 0.493 |

| History of biologics, n (%) | 6 (20.0) | 6 (35.3) | 0.306 |

| Time to high trough level (d), mean ± SD | 7.9 ± 8.1 | 8.5 ± 6.4 | 0.773 |

We compared biological data between the remission and failure groups before the start of treatment (week 0), 1 wk after the start of observation (week 1), and 2 wk after the start of observation (week 2) (Table 3). No significant difference was observed regarding the biological data before the start of treatment (week 0) between the two groups. There was no significant difference in biological data in week 1, and only serum Alb level in week 2 showed a significant difference between the remission and failure groups (P = 0.015).

| Biological data | Remission (n = 30) | Failure (n = 17) | P value |

| Serum Alb at week 0 (g/dL) | 2.83 ± 0.68 | 2.81 ± 0.72 | 0.897 |

| Serum Alb at week 1 (g/dL) | 2.94 ± 0.61 | 2.85 ± 0.78 | 0.651 |

| Serum Alb at week 2 (g/dL) | 3.29 ± 0.57 | 2.81 ± 0.73 | 0.015 |

| Serum CRP at week 0 (mg/dL) | 5.58 ± 5.75 | 5.44 ± 5.45) | 0.933 |

| Serum CRP at week 1 (mg/dL) | 0.88 ± 2.29 | 1.12 ± 1.51 | 0.696 |

| Serum CRP at week 2 (mg/dL) | 0.54 ± 1.50 | 1.17 ± 1.63 | 0.191 |

| Hb at week 0 (g/dL) | 11.2 ± 1.90 | 11.32 ± 2.06 | 0.871 |

| Hb at week 1 (g/dL) | 10.65 ± 1.60 | 11.15 ± 1.77 | 0.326 |

| Hb at week 2 (g/dL) | 10.78 ± 1.71 | 10.89 ± 1.88 | 0.837 |

| WBC at week 0 (/μL) | 8660.00 ± 4498.65 | 8846.47 ± 3876.21 | 0.887 |

| WBC at week 1 (/μL) | 5958.00 ± 2444.20 | 6618.24 ± 2201.22 | 0.362 |

| WBC at week 2 (/μL) | 5473.00 ± 2095.78 | 6672.35 ± 2154.37 | 0.069 |

In order to compare the changes in biological data before and after the start of treatment between the remission group and the failure group, the percentage of each value based on week 0 was calculated (Table 4). The week 1/week 0 ratio showed no significant difference in Alb, CRP, Hb, and WBC values. The week 2/week 0 ratio was significantly different only for Alb values between the remission and failure groups (P = 0.003).

| Rate of biological data | Remission (n = 30) | Failure (n = 17) | P value |

| Week 1/week 0 Alb ratio | 1.05 ± 0.14 | 1.02 ± 0.13 | 0.429 |

| Week 2/week 0 Alb ratio | 1.19 ± 0.20 | 1.02 ± 0.16 | 0.003 |

| Week 1/week 0 CRP ratio | 0.28 ± 0.49 | 1.28 ± 3.80 | 0.159 |

| Week 2/week 0 CRP ratio | 0.16 ± 0.23 | 1.42 ± 4.28 | 0.112 |

| Week 1/week 0 Hb ratio | 0.96 ± 0.13 | 1.01 ± 0.18 | 0.315 |

| Week 2/week 0 Hb ratio | 0.97 ± 0.13 | 0.98 ± 0.14 | 0.892 |

| Week 1/week 0 WBC ratio | 0.77 ± 0.32 | 0.84 ± 0.33 | 0.520 |

| Week 2/week 0 WBC ratio | 0.72 ± 0.30 | 0.86 ± 0.40 | 0.194 |

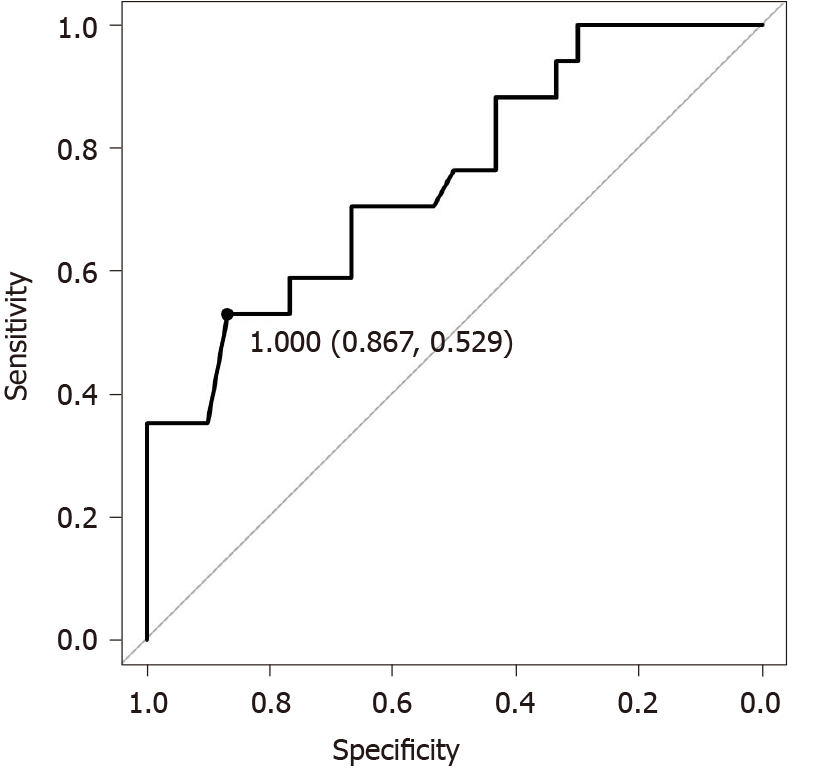

Since it was shown that the week 2/week 0 Alb ratio may be a factor predicting clinical failure for 3 mo, ROC analysis was performed using this ratio (Figure 1). The cut-off Alb ratio for week 2/week 0 was 1, and its sensitivity and specificity were 0.539 and 0.867, respectively. The AUC was 0.751 (95%CI: 0.604-0.898).

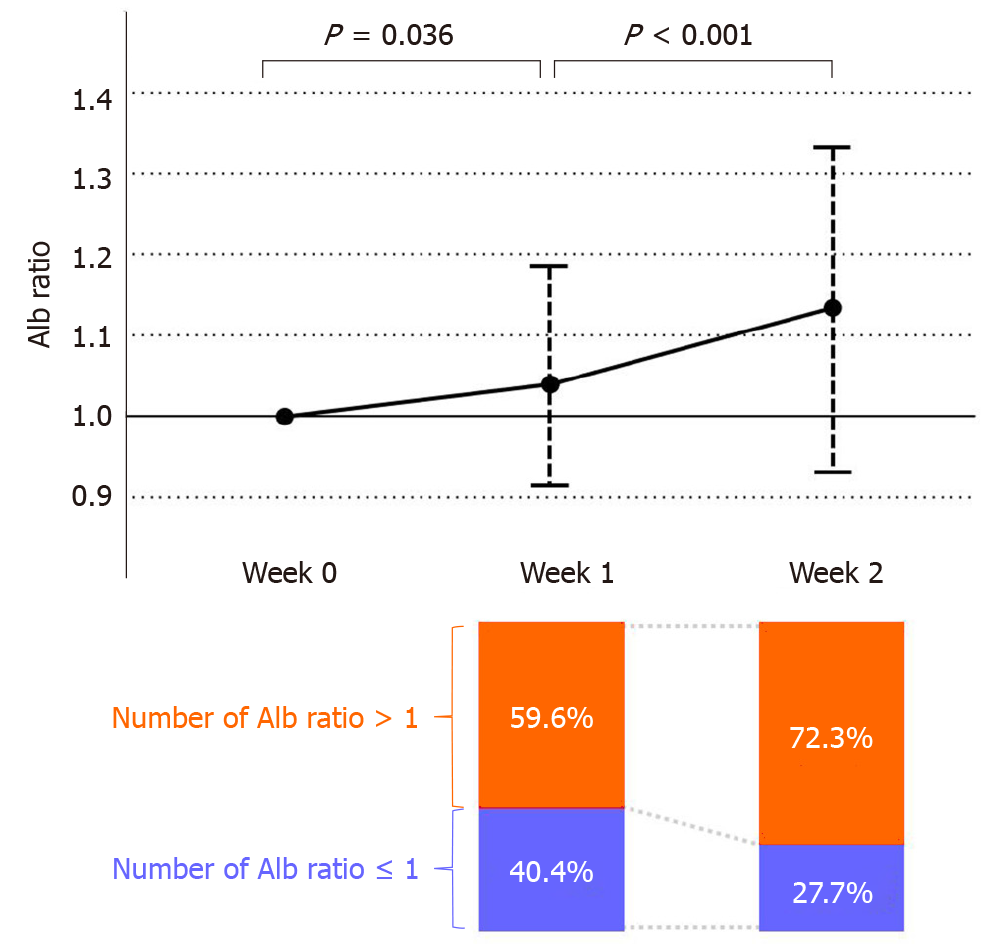

Furthermore, in order to investigate the reason for the cut-off value of 1 by week 2, we investigated the change in the Alb ratio (Figure 2). The Alb ratio increased significantly from week 0 to week 1 and showed a further increase from week 1 to week 2 (P = 0.036 and P < 0.001, respectively). In addition, when the Alb ratio was examined from the viewpoint of whether it was more or less than 1 in value, 40.4% of the patients in week 1 had an Alb ratio ≤ 1 (Figure 2). In contrast, at week 2, the number of patients with Alb ratio ≤ 1 decreased to 27.2%, and the number of patients with an Alb ratio > 1 increased to 72.8%.

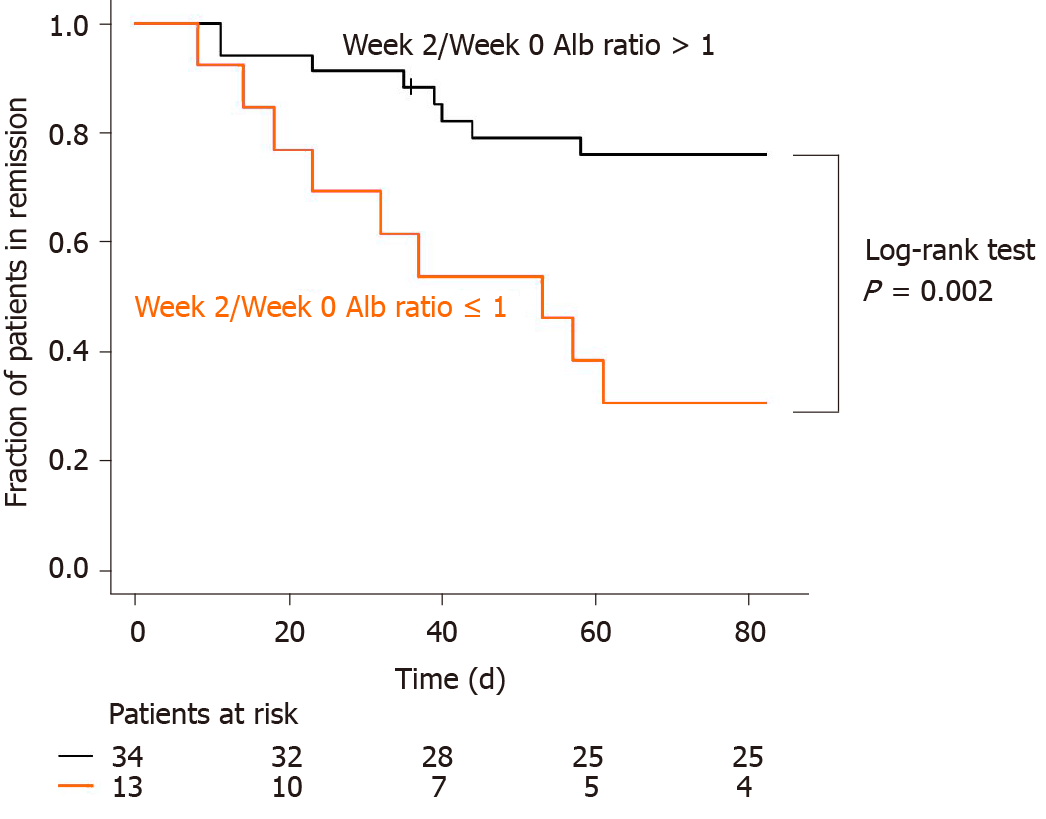

We compared the fractions of patients in remission between the week 2/week 0 Alb ratio > 1 group and week 2/week 0 Alb ratio ≤ 1 group using the Kaplan-Meier curve (Figure 3). There were 34 and 14 patients with week 2/week 0 Alb ratio > 1 and week 2/week 0 Alb ratio ≤ 1, respectively. Nine patients in both groups had clinical failures during the 3-mo follow-up. Patients with week 2/week 0 Alb ratio ≤ 1 had a significantly higher rate of clinical failure than patients with week 2/week 0 Alb ratio > 1 (log-rank test: P = 0.002). In addition, Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed for week 2/week 0 Alb ratio > 1 (Table 5). Week 2/week 0 Alb ratio ≤ 1 was shown by univariate and multivariate analyses to be an independent prognostic factor that resulted in increased rates of clinical failure within 3 mo of induction of tacrolimus treatment.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Week 2/week 0 Alb ratio ≤ 1 | 3.632 | 1.396-9.445 | 0.008 | 7.195 | 2.011-25.74 | 0.002 |

| Age | 1.026 | 0.998-1.055 | 0.072 | 1.009 | 0.976-1.042 | 0.599 |

| Sex (male) | 2.139 | 0.489-9.362 | 0.313 | 2.420 | 0.435-13.45 | 0.313 |

| Disease extent (extensive colitis) | 1.062 | 0.243-4.640 | 0.937 | 4.665 | 0.554-39.30 | 0.157 |

| MES 3 | 1.188 | 0.341-4.137 | 0.787 | 0.462 | 0.142-1.503 | 0.200 |

| Medication | ||||||

| Oral 5-ASA | 0.450 | 0.158-1.277 | 0.133 | 0.578 | 0.191-1.744 | 0.331 |

| Suppository 5-ASA | 0.652 | 0.149-2.853 | 0.570 | 0.247 | 0.035-1.744 | 0.161 |

| Systemic steroids | 0.729 | 0.281-1.890 | 0.515 | 0.636 | 0.193-2.094 | 0.457 |

| Immunomodulators | 1.152 | 0.375-3.543 | 0.805 | 1.516 | 0.391-5.885 | 0.548 |

| Biologics | 1.400 | 0.493-3.978 | 0.527 | 0.924 | 0.173-4.920 | 0.926 |

This study aimed to explore factors that could predict the prognosis of oral tacrolimus for UC. In particular, the analysis focused on biological data, which is a marker widely used in clinical practice. Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor used in patients with steroid-dependent or refractory UC and is indicated for moderate to severe cases. However, there are some cases in which colectomy is unavoidable due to ineffective treatment with tacrolimus. Approximately 6.1%-66.7% patients who were treated with tacrolimus underwent colectomy[6-8,20-26]. Therefore, the possibility of performing colectomy in the future should be considered, especially when starting treatment with tacrolimus for patients with very severe UC.

Conventionally, surgical treatment for IBD has many potential perioperative complications, and poor nutrition further increases the risk of postoperative complications[11,27]. Unnecessarily prolonging preoperative medical treatment will worsen the nutritional status of patients with UC, and surgical treatment in that malnourished state will further increase the risk of postoperative complications. It is extremely important to judge the effectiveness of treatment for UC at an early stage and to consider the next treatment before the general condition worsens. In this study, we searched for prognostic factors that could predict the efficacy of tacrolimus based on clinical laboratory data.

In this study, we investigated the values of Alb, CRP, Hb, and WBC before the induction of tacrolimus (week 0) and at 1- and 2 wk after achieving high trough levels (week 1 and week 2, respectively). There was a significant difference in serum Alb levels at week 2 between the remission and failure groups, but there was no significant difference in CRP, a biomarker that reflects systemic or local inflammation. Since each Alb value before the start of treatment varies with each patient, the ratio of week 1 Alb value or week 2 Alb value divided by week 0 Alb value was calculated in this study. As a result, the week 2/week 0 Alb ratio showed a significant difference between the remission and failure groups. In the treatment of ulcerative colitis with tacrolimus, a sufficient therapeutic effect is exhibited, and mucosal healing is induced, by promptly reaching the effective range of blood concentration after the start of tacrolimus treatment. Therefore, in cases in which tacrolimus is effective, albumin is elevated because leakage of albumin from the intestinal tract is limited by mucosal healing. However, mucosal healing is not achieved in patients in whom tacrolimus is ineffective; therefore, it is thought that albumin loss from the intestinal tract persists and hypoalbuminemia does not improve. Although not shown in the data, the clinical activity index, which evaluated bloody stools and diarrhea, showed a greater improvement from week 0 to week 2 in the non-failure group than in the failure group.

We considered the factors leading to the significant difference in the Alb value by week 2 between groups; however, no significant difference was shown in Week 1. As shown in Figure 2, a significant increase in the Alb ratio was observed from Week 0 to Week 1, and a further significant increase was observed from Week 1 to Week 2 overall. Furthermore, as a result of examining the proportion of patients with an Alb ratio of 1 as the cut-off value in weeks 1 and 2, patients with an Alb ratio ≤ 1 (patients whose Alb value did not change or decrease in week 1 compared to week 0) comprised 40.4%, which was close to half. The reason for this may be that frequent diarrhea and bloody stools before the administration of tacrolimus may cause intravascular dehydration, resulting in higher Alb levels in blood. However, it was considered that after starting treatment, blood might have been diluted due to intravenous hydration in many patients, resulting in a temporary decrease in Alb levels. For this reason, the Alb level tends to decrease temporarily after the start of treatment, so it is too early to evaluate the Alb level by week 1, and judgment at week 2 was considered to be appropriate.

Lee et al[28] reported that determination of Alb levels at week 2 was important for anti-TNF treatment in UC, which is similar to our analysis. This report showed that the Alb value 2 wk after the start of anti-TNF treatment was associated with primary nonresponse, endoscopic outcomes, time-to-colectomy, and anti-TNF failure.

Several reports have attempted to predict the effect of tacrolimus on UC. Miyoshi et al[7] reported that colonoscopy evaluation 3 mo after remission induction with tacrolimus showed that groups with MES 0 and 1 had a better subsequent clinical course than the groups with MES 2 and 3. In addition to this report, there have been several other reports on the treatment responsiveness and prognosis of tacrolimus on UC. In the report by Ban et al[16], an analysis focusing on Alb was performed similar to that in our study. Their study also examined patients with UC who received calcineurin inhibitors, including cyclosporine and tacrolimus, and who underwent colectomy within 60 d of their remission induction. The study reported that the mean Alb levels of the early colectomy group and the non-early colectomy group before tacrolimus treatment were 2.95 and 3.41, respectively, and that low Alb levels were a risk for early colectomy (P = 0.0256). However, in our study, the mean Alb levels before the start of tacrolimus in the failure and remission groups were 2.81 and 2.83, respectively, showing no significant difference. The mean Alb levels before the induction of tacrolimus in all cases were 3.3 and 2.82 in the study by Ban et al[16] and the present study, respectively; however, more patients had hypoalbuminemia before the start of treatment in our institution. This seems to be the reason for the difference in the results between the two clinical studies. In our study, 17 of 47 patients had clinical failure during a 3-mo follow-up, and the remission rate was 63.8%. Although there are differences in the observation period and the severity of enrolled patients, previous reports of the effects of tacrolimus on UC have reported a remission rate ranging from 9.4-75.6%[4-8,21-26,29].

In this study, even if the Alb level at week 0 was low, we could predict an effective remission if the albumin ratio was high in our study. Specifically, in the sub-group of Alb < 3 (n = 25), the week 2/week 0 Alb ratio of the failure group was significantly higher than that of the remission group (P = 0.003). In addition, a ROC analysis of the Alb < 3 sub-group showed a cut-off value of 1.235 and AUC of 0.853 with a 95%CI of 0.705-1.000. We considered that the AUC of Alb < 3 was higher than the AUC of all cases because low Alb levels at Week 0 could be slightly increased after treatment improved the condition of UC.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a single-center retrospective study with few enrolled patients. Second, we did not evaluate certain fecal biomarkers that have recently become widely used. Fecal biomarkers used in UC not only reflect endoscopic scores, but can also predict clinical relapse. There have been several recent reports on the usefulness of fecal calprotectin and fecal immunochemical occult blood test [30-35]. However, it has not been verified whether these biomarkers are useful for evaluating the therapeutic effect and predicting prognosis in treatment using tacrolimus for UC, which is a subject for future research. In addition, this study evaluated Alb levels 2 wk after achieving high trough levels of tacrolimus as it is not beneficial for patients to postpone the decision to convert to surgical treatment beyond this time point. Indeed, early conversion to surgical treatment in steroid-refractory acute severe UC has been reported to improve postoperative prognosis[36,37]. Conversely, prolongation of preoperative medical treatment for refractory cases has been reported to worsen the postoperative prognosis of UC[38,39]. Alternatively, switching to other biologics may not improve the condition of UC patients, but rather increase the risk of complications. Therefore, we thought that the prediction of the prognosis in moderate to severe UC via the Alb ratio, as shown in this study, could be a supportive factor in determining the next treatment.

In conclusion, a lower Alb value in week 2 than in week 0 after achieving trough level of tacrolimus predicts clinical failure in patients with UC. In these cases, changes to other treatment options, including surgical total colectomy, should be considered as soon as possible.

There are cases of refractory ulcerative colitis in which tacrolimus does not induce remission.

A biomarker capable of predicting the induction effect of tacrolimus is desired.

The usefulness of serum albumin as a predictor of the therapeutic effect of oral tacrolimus for ulcerative colitis was investigated.

Patients treated with tacrolimus at our hospital were divided into a remission group and a failure group, and data including serum albumin at the start of observation and at the first and second weeks were retrospectively examined.

Lower albumin levels in week 2 than in week 0 after achieving trough levels of tacrolimus were shown to increase risk for failure, including colectomy and switch to biologics, within 3 mo.

Early serum albumin changes in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with tacrolimus predict clinical outcome.

In cases where albumin levels in week 2 are lower than week 0, changes to other treatment options, including surgical total colectomy, should be considered as soon as possible.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Stein J, Zhang H S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2199] [Cited by in RCA: 2485] [Article Influence: 310.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Faubion WA Jr, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 833] [Cited by in RCA: 792] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:103-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ogata H, Matsui T, Nakamura M, Iida M, Takazoe M, Suzuki Y, Hibi T. A randomised dose finding study of oral tacrolimus (FK506) therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2006;55:1255-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ogata H, Kato J, Hirai F, Hida N, Matsui T, Matsumoto T, Koyanagi K, Hibi T. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral tacrolimus (FK506) in the management of hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:803-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yamamoto S, Nakase H, Mikami S, Inoue S, Yoshino T, Takeda Y, Kasahara K, Ueno S, Uza N, Kitamura H, Tamaki H, Matsuura M, Inui K, Chiba T. Long-term effect of tacrolimus therapy in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:589-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miyoshi J, Matsuoka K, Inoue N, Hisamatsu T, Ichikawa R, Yajima T, Okamoto S, Naganuma M, Sato T, Kanai T, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Hibi T. Mucosal healing with oral tacrolimus is associated with favorable medium- and long-term prognosis in steroid-refractory/dependent ulcerative colitis patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e609-e614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ikeya K, Sugimoto K, Kawasaki S, Iida T, Maruyama Y, Watanabe F, Hanai H. Tacrolimus for remission induction in ulcerative colitis: Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 and 1 predict long-term prognosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:365-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Endo K, Onodera M, Shiga H, Kuroha M, Kimura T, Hiramoto K, Kakuta Y, Kinouchi Y, Shimosegawa T. A Comparison of Short- and Long-Term Therapeutic Outcomes of Infliximab- versus Tacrolimus-Based Strategies for Steroid-Refractory Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3162595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Markel TA, Lou DC, Pfefferkorn M, Scherer LR 3rd, West K, Rouse T, Engum S, Ladd A, Rescorla FJ, Billmire DF. Steroids and poor nutrition are associated with infectious wound complications in children undergoing first stage procedures for ulcerative colitis. Surgery. 2008;144:540-5; discussion 545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Okita Y, Araki T, Okugawa Y, Kondo S, Fujikawa H, Hiro J, Inoue M, Toiyama Y, Ohi M, Uchida K, Kusunoki M. The prognostic nutritional index for postoperative infectious complication in patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing proctectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis following subtotal colectomy. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2019;3:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, D'Haens GR, Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Danese S, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Niezychowski W, Friedman G, Lawendy N, Yu D, Woodworth D, Mukherjee A, Zhang H, Healey P, Panés J; OCTAVE Induction 1; OCTAVE Induction 2, and OCTAVE Sustain Investigators. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 1189] [Article Influence: 148.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, O'Brien CD, Zhang H, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Li K, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Van Assche G, Danese S, Targan S, Abreu MT, Hisamatsu T, Szapary P, Marano C; UNIFI Study Group. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 828] [Article Influence: 138.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, Danese S, Colombel JF, Törüner M, Jonaitis L, Abhyankar B, Chen J, Rogers R, Lirio RA, Bornstein JD, Schreiber S; VARSITY Study Group. Vedolizumab versus Adalimumab for Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 560] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 83.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nishida Y, Hosomi S, Yamagami H, Sugita N, Itani S, Yukawa T, Otani K, Nagami Y, Tanaka F, Taira K, Kamata N, Tanigawa T, Watanabe T, Fujiwara Y. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts clinical relapse of ulcerative colitis after tacrolimus induction. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ban H, Bamba S, Nishida A, Inatomi O, Shioya M, Takahashi KI, Imaeda H, Murata M, Sasaki M, Tsujikawa T, Andoh A. Prognostic factors affecting early colectomy in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis treated with calcineurin inhibitors. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:829-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Herrlinger KR, Koc H, Winter S, Teml A, Stange EF, Fellermann K, Fritz P, Schwab M, Schaeffeler E. ABCB1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms determine tacrolimus response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:422-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1958] [Cited by in RCA: 2251] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. BMJ. 1989;298:82-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 771] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Högenauer C, Wenzl HH, Hinterleitner TA, Petritsch W. Effect of oral tacrolimus (FK 506) on steroid-refractory moderate/severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:415-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Benson A, Barrett T, Sparberg M, Buchman AL. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus in refractory ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: a single-center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:7-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thin LW, Murray K, Lawrance IC. Oral tacrolimus for the treatment of refractory inflammatory bowel disease in the biologic era. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1490-1498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schmidt KJ, Herrlinger KR, Emmrich J, Barthel D, Koc H, Lehnert H, Stange EF, Fellermann K, Büning J. Short-term efficacy of tacrolimus in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis - experience in 130 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:129-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Landy J, Wahed M, Peake ST, Hussein M, Ng SC, Lindsay JO, Hart AL. Oral tacrolimus as maintenance therapy for refractory ulcerative colitis--an analysis of outcomes in two London tertiary centres. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e516-e521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kawakami K, Inoue T, Murano M, Narabayashi K, Nouda S, Ishida K, Abe Y, Nogami K, Hida N, Yamagami H, Watanabe K, Umegaki E, Nakamura S, Arakawa T, Higuchi K. Effects of oral tacrolimus as a rapid induction therapy in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1880-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Saifuddin A, Harris A. Tacrolimus therapy in moderate to subacute ulcerative proctocolitis: a large single-centre cohort study. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2018;9:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gu J, Stocchi L, Remzi F, Kiran RP. Factors associated with postoperative morbidity, reoperation and readmission rates after laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1123-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lee SH, Walshe M, Oh EH, Hwang SW, Park SH, Yang DH, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Greener T, Weizman AV, Silverberg MS, Ye BD. Early Changes in Serum Albumin Predict Clinical and Endoscopic Outcomes in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Starting Anti-TNF Treatment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hiraoka S, Kato J, Moritou Y, Takei D, Inokuchi T, Nakarai A, Takahashi S, Harada K, Okada H, Yamamoto K. The earliest trough concentration predicts the dose of tacrolimus required for remission induction therapy in ulcerative colitis patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hiraoka S, Kato J, Nakarai A, Takashima S, Inokuchi T, Takei D, Sugihara Y, Takahara M, Harada K, Okada H. Consecutive Measurements by Faecal Immunochemical Test in Quiescent Ulcerative Colitis Patients Can Detect Clinical Relapse. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:687-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Naganuma M, Kobayashi T, Nasuno M, Motoya S, Kato S, Matsuoka K, Hokari R, Watanabe C, Sakamoto H, Yamamoto H, Sasaki M, Watanabe K, Iijima H, Endo Y, Ichikawa H, Ozeki K, Tanida S, Ueno N, Fujiya M, Sako M, Takeuchi K, Sugimoto S, Abe T, Hibi T, Suzuki Y, Kanai T. Significance of Conducting 2 Types of Fecal Tests in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 1102-1111. e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nakarai A, Hiraoka S, Takahashi S, Inaba T, Higashi R, Mizuno M, Takashima S, Inokuchi T, Sugihara Y, Takahara M, Harada K, Kato J, Okada H. Simultaneous Measurements of Faecal Calprotectin and the Faecal Immunochemical Test in Quiescent Ulcerative Colitis Patients Can Stratify Risk of Relapse. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yamamoto T, Shimoyama T, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Endoscopic score vs. fecal biomarkers for predicting relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis after clinical remission and mucosal healing. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018;9:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Urushikubo J, Yanai S, Nakamura S, Kawasaki K, Akasaka R, Sato K, Toya Y, Asakura K, Gonai T, Sugai T, Matsumoto T. Practical fecal calprotectin cut-off value for Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4384-4392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Buisson A, Mak WY, Andersen MJ, Lei D, Kahn SA, Pekow J, Cohen RD, Zmeter N, Pereira B, Rubin DT. Faecal Calprotectin Is a Very Reliable Tool to Predict and Monitor the Risk of Relapse After Therapeutic De-escalation in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:1012-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Leeds IL, Truta B, Parian AM, Chen SY, Efron JE, Gearhart SL, Safar B, Fang SH. Early Surgical Intervention for Acute Ulcerative Colitis Is Associated with Improved Postoperative Outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1675-1682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Saha SK, Panwar R, Kumar A, Pal S, Ahuja V, Dash NR, Makharia G, Sahni P. Early colectomy in steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis improves operative outcome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:79-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Coakley BA, Telem D, Nguyen S, Dallas K, Divino CM. Prolonged preoperative hospitalization correlates with worse outcomes after colectomy for acute fulminant ulcerative colitis. Surgery. 2013;153:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kim IK, Park KJ, Kang GH, Im JP, Kim SG, Jung HC, Song IS, Kim JS. Risk factors for complications after total colectomy in ulcerative colitis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012;23:515-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |