Published online Apr 28, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i16.1841

Peer-review started: December 21, 2020

First decision: January 23, 2021

Revised: February 5, 2021

Accepted: March 16, 2021

Article in press: March 16, 2021

Published online: April 28, 2021

Processing time: 114 Days and 11.2 Hours

Gastric pull-up (GPU) procedures may be complicated by leaks, fistulas, or stenoses. These complications are usually managed by endoscopy, but in extreme cases multidisciplinary management including reoperation may be necessary. Here, we report a combined endoscopic and surgical approach to manage a failed secondary GPU procedure.

A 70-year-old male with treatment-refractory cervical esophagocutaneous fistula with stenotic remnant esophagus after secondary GPU was transferred to our tertiary hospital. Local and systemic infection originating from the infected fistula was resolved by endoscopy. Hence, elective esophageal reconstruction with free-jejunal interposition was performed with no subsequent adverse events.

A multidisciplinary approach involving interventional endoscopists and surgeons successfully managed severe complications arising from a cervical esophago-cutaneous fistula after GPU. Endoscopic treatment may have lowered the perioperative risk to promote primary wound healing after free-jejunal graft interposition.

Core Tip: Gastric pull-up (GPU) reconstruction after esophagectomy may be complicated by leaks, fistulas, and stenoses. In such cases, endoscopic interventions, including endoscopic vacuum therapy, stenting, or dilatation, are the corrective treatments of choice, but surgery is preferred when esophageal reconstruction becomes necessary. Here, we report a case of esophageal reconstruction after a secondary GPU procedure by combining endoscopic and surgical techniques to perform subtotal esophageal resection and reconstruction using a free-jejunal graft interposition.

- Citation: Lock JF, Reimer S, Pietryga S, Jakubietz R, Flemming S, Meining A, Germer CT, Seyfried F. Managing esophagocutaneous fistula after secondary gastric pull-up: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(16): 1841-1846

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i16/1841.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i16.1841

Gastric pull-up (GPU) procedures may be complicated by leaks, fistulas, and stenoses. In such cases, restoration of the esophagus and adequate recovery of alimentation becomes challenging[1]. Endoscopic interventions, including endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT), stenting, or dilatation, are the corrective treatments of choice[2], but surgery is preferred when esophageal reconstruction becomes necessary[3]. Here, we report a case of esophageal reconstruction after a secondary GPU procedure by combining endoscopic and surgical techniques.

A 70-year-old male patient underwent emergency esophageal diversion after injury to the cervical esophagus during spinal surgery.

Six months later, retrosternal GPU procedure was performed but postoperative anastomotic leakage occurred. The leakage was successfully managed by endoscopy and the patient was discharged with a fully covered esophageal stent in place. Three weeks later, local cervical infection and sepsis developed. At this time, our tertiary university hospital was contacted for patient transfer.

Notable previous illnesses were arterial hypertonus, non-active smoking status and an ischemic stroke with incomplete senso-motoric hemiparesis. Furthermore, the patient had a thyroidectomy in the past and open prostatectomy due to prostate cancer.

The patient had no family history that was related to the present illness.

On admission, the patient showed clear signs of malnutrition and systemic inflammation with jugular and cervical phlegmon.

Initial laboratory data revealed a hemoglobin level of 6.7 g/dL, white blood cell count of 6400 cells/μL, and platelet count of 210 × 103/μL. The creatinine level was 0.76 mg/dL, unremarkable liver and cholestasis parameters, and albumin level was 2.8 g/dL.

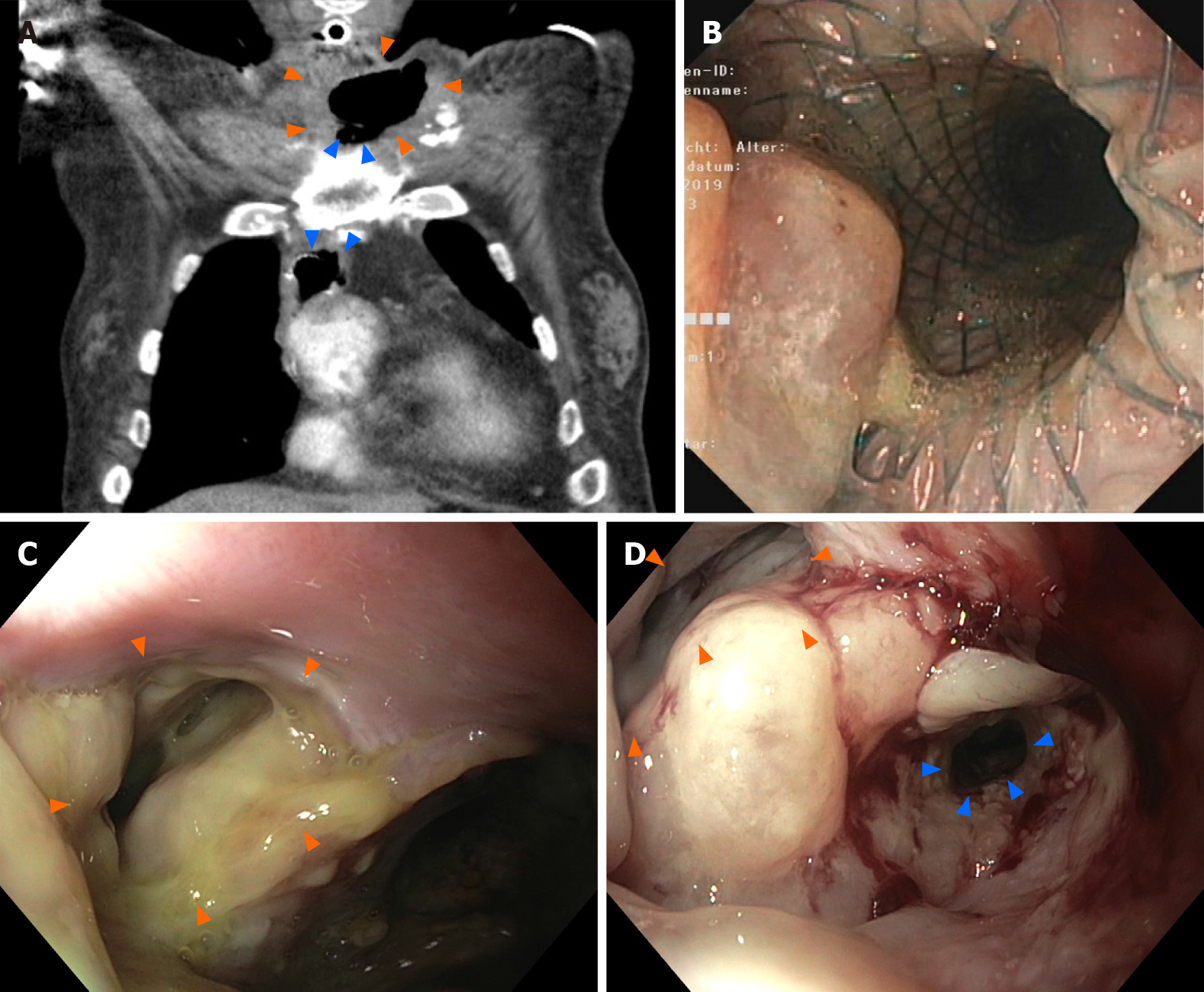

A chest computed tomography (CT) scan and endoscopy revealed a dislodged esophageal stent, with the proximal flare abutting an extraesophageal air and fluid-filled cavity (Figure 1). During stent removal, a partially epithelialized esophageal perforation 2 cm distal to the pharynx with an infected cavity (Figure 1B and C) as well as a 5 cm-long stenosis of the remaining esophagus were detected.

Diagnosis of cervical esophagocutaneous fistula and anastomotic stenosis after GPU with signs of chronic malnutrition and systemic inflammation.

The patient received calculated antibiotic treatment and was transferred to the intensive care unit. An immediate endoscopy was carried out, and the dislocated stent (partially covered metal stent, length 80 mm, diameter 18 mm) was removed. Endoscopy showed an old, partially epithelialized and wide esophageal perforation 2 cm distal of the pharynx with an infected cavity behind it. Distal of the fistula, a long-segment (5 cm) stenosis of the esophagus ranging up to the esophago-gastrostomy was confirmed. Notably, the perforation and the fistula cavity were likely to be a secondary injury due to the dislocated cervical stent tulip (diameter 24 mm). After pus evacuation and debridement of the fistula, a fully covered self-expanding metal stent (length 100 mm, diameter 20 mm) was inserted in order to cover the fistula and to treat the stenosis. Due to an expected long-term course, a percutaneous jejunal feeding catheter was surgically inserted to ensure sufficient enteral nutrition. The first re-endoscopy revealed a slippage of the stent so that the cranial fistula ostium was not sufficiently covered. The stent position was successfully corrected but dislocated again during follow-up.

Thus, endoscopic management was switched to EVT. An EsoSponge system (B. Braun Melsungen, Germany) was placed into the esophagocutaneous fistula ostium (cavity). The jugular and cervical phlegmon resolved during EVT within two weeks and repeated endoscopic balloon dilatation was performed to resolve the esophageal stenosis. However, it became obvious that endoscopic management could not resolve the broad and rigid fistula with the concomitant partially obliterated esophagus. The issue was discussed interdisciplinarily and the therapeutic aim of endoscopy was redefined: Profound consolidation of the cervical infection and cleaning of the fistula cavity until salvage surgery (Figure 1D).

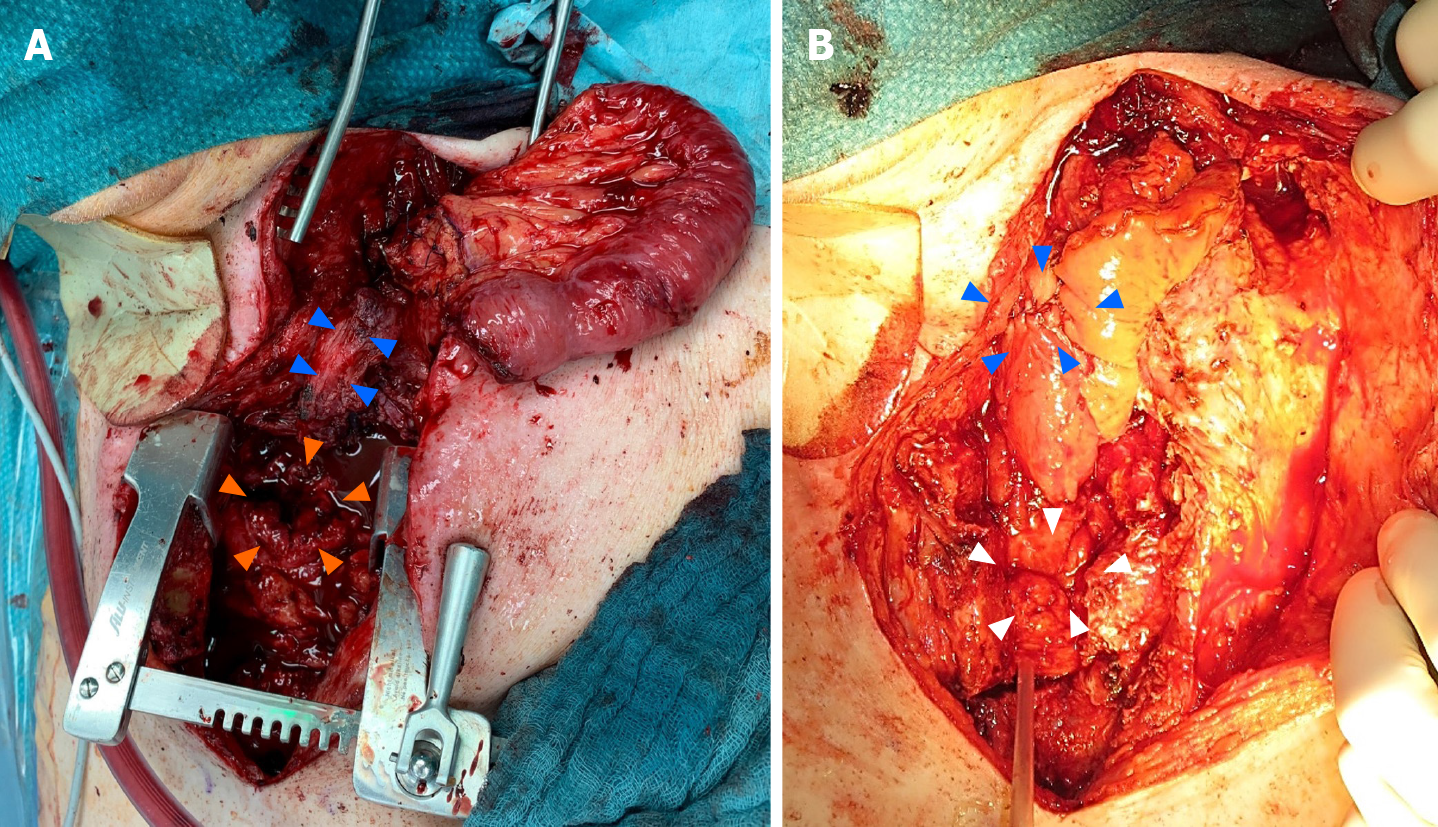

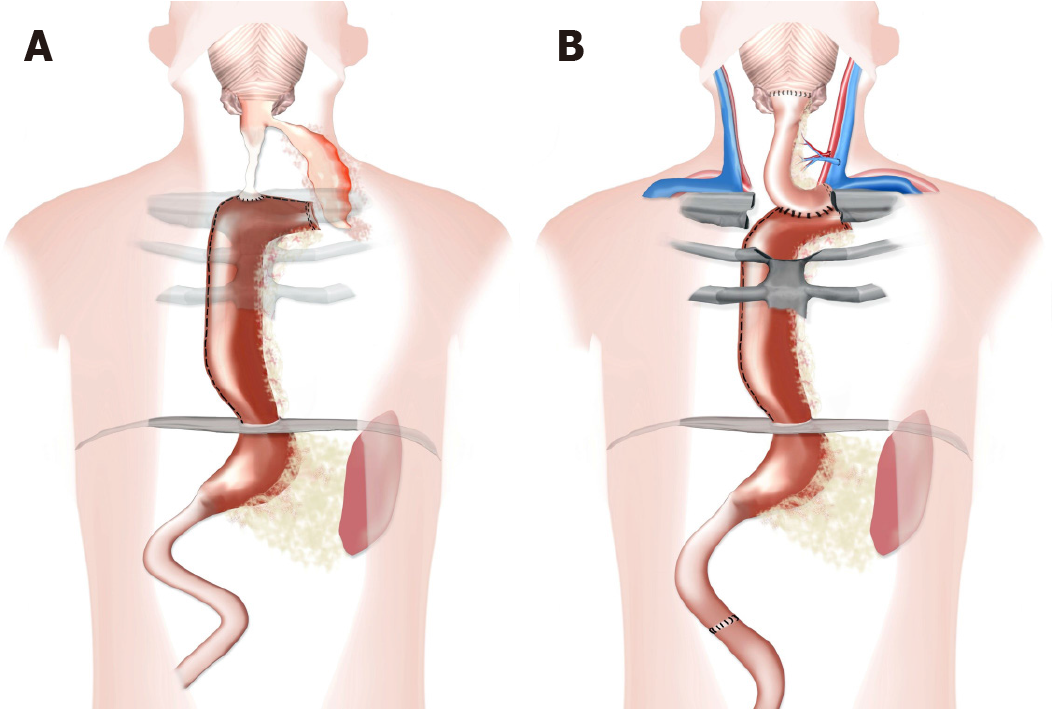

The cervical phlegmon resolved within two weeks, allowing subtotal esophageal resection and reconstruction using a free-jejunal graft interposition according to Ott et al[4]. Pre-operative work up included CT angiography to establish the feasibility of vascular reconstruction. Partial sternotomy was necessary to provide access to the esophagus and the stomach (Figure 2A). After resection of the cervical esophagus and fistula, the exploration confirmed that the GPU could not be mobilized up to the pharynx. Thus, laparotomy was performed and a suitable jejunal segment was harvested. The left carotid artery and the left jugular vein were used as recipient vessels. The graft was implanted in an isoperistaltic position. The cervical anastomosis was performed in an end-to-end fashion and the upper mediastinal gastro-jejunostomy in a side-to-side fashion (Figure 2B). A part of the upper sternum was resected to avoid any pressure on the graft and gastrojejunostomy. The soft tissue defect was covered with a sternocleidomastoid muscle flap. Abdominal reconstruction was achieved by an end-to-end jejunojejunostomy.

The postoperative course was uneventful. Oral alimentation was reestablished accompanied with daily speech therapy. Anastomotic healing was confirmed radiologically and endoscopically and the patient was transferred to a rehabilitation clinic in good clinical condition.

Esophagectomy with diversion and later reconstruction of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract is reserved for complex esophageal disease[5]. Despite numerous advantages over alternative reconstruction techniques, anastomotic complications following GPU procedures occur in up to 12% of cases[6].

Managing anastomotic leakage or stricture of GPU can be extremely challenging because of local tissue damage from previous surgery or chronic infection[1,7]. Endoscopic management of leaks, fistulas and stenosis in the upper GI tract has therefore not only become a valuable tool, but the standard approach for successful management even in complex situations[8,9]. Here, it is extremely important to carefully consider and constantly evaluate the local tissue and wound conditions. In our case, the constant pressure caused by the stent itself may have further deteriorated the esophageal wall and, thus, may have caused perforation and fistula with abscess formation since no external drainage had been established.

The surgical options available for the management of a complicated GPU procedure are limited and usually contain a high risk of morbidity and mortality[5]. Esophageal reconstruction with a free jejunal graft was introduced by Seidenberg and colleagues in 1959 and later modified by Siewert and colleagues in 2008 for treating cancer of the cervical esophagus[4,10]. The use of a salvage option after failed GPU has also been described[12]. Recent data regarding follow-up results in esophageal reconstruction strongly suggest the superiority of intestinal flaps over other reconstructions such as skin flaps.

High failure rates for secondary attempts after failed esophageal reconstruction have been described[1], with a complication rate in excess of 70%[11]. However, free jejunal grafts have considerable advantages. They are usually easy to harvest, provide low donor-site morbidity, have good size approximation to the cervical esophagus, tolerate reflux well, and have a low rate of peptic ulceration incidence[12]. Dis-advantages include the need for transient ischemia that requires advanced microsurgical skills for swift revascularization and a challenging surgical site environment because of previous surgery and infection.

A multidisciplinary approach involving interventional endoscopists and surgeons was necessary to enable successful salvage management. Despite prior complications, operations and chronic infection, restoration and reconstruction of the esophagus was ultimately achieved (Figure 3). Thus, patients with chronic postoperative fistulas or stenoses of the esophagus should be referred to specialized centers in a timely manner.

We would like to thank Mrs. Anna Maria Kellersmann for preparation of Figure 3 and Dr. Mohammed Hankir for proofreading the manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Germany

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Couto-Worner I, Eysselein VE S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Okazaki M, Asato H, Takushima A, Nakatsuka T, Ueda K, Harii K. Secondary reconstruction of failed esophageal reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54:530-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Scognamiglio P, Reeh M, Karstens K, Bellon E, Kantowski M, Schön G, Zapf A, Chon SH, Izbicki JR, Tachezy M. Endoscopic vacuum therapy vs stenting for postoperative esophago-enteric anastomotic leakage: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2020;52:632-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Moore JM, Hooker CM, Molena D, Mungo B, Brock MV, Battafarano RJ, Yang SC. Complex Esophageal Reconstruction Procedures Have Acceptable Outcomes Compared With Routine Esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:215-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ott K, Lordick F, Molls M, Bartels H, Biemer E, Siewert JR. Limited resection and free jejunal graft interposition for squamous cell carcinoma of the cervical oesophagus. Br J Surg. 2009;96:258-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | DiPierro FV, Rice TW, DeCamp MM, Rybicki LA, Blackstone EH. Esophagectomy and staged reconstruction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17:702-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Butskiy O, Rahmanian R, White RA, Durham S, Anderson DW, Prisman E. Revisiting the gastric pull-up for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality and morbidity. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:907-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Suga H, Okazaki M, Sarukawa S, Takushima A, Asato H. Free jejunal transfer for patients with a history of esophagectomy and gastric pull-up. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:182-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Neumann PA, Dhayat S, Horst G, Palmes D, Senninger N, Vowinkel T. Successful closure of defects in the upper gastrointestinal tract by endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT): a prospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2687-2696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Seyfried F, Reimer S, Miras AD, Kenn W, Germer CT, Scheurlen M, Jurowich C. Successful treatment of a gastric leak after bariatric surgery using endoluminal vacuum therapy. Endoscopy. 2013;45 Suppl 2:E267-E268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Seidenberg B, Rosenak SS, Hurwitt ES, Som ML. Immediate reconstruction of the cervical esophagus by a revascularized isolated jejunal segment. Ann Surg. 1959;149:162-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sacak B, Orfaniotis G, Nicoli F, Liu EW, Ciudad P, Chen SH, Chen HC. Back-up procedures following complicated gastric pull-up procedure for esophageal reconstruction: Salvage with intestinal flaps. Microsurgery. 2016;36:567-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gaur P, Blackmon SH. Jejunal graft conduits after esophagectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6 Suppl 3:S333-S340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |