Published online Jan 7, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i1.129

Peer-review started: October 11, 2020

First decision: November 23, 2020

Revised: November 28, 2020

Accepted: December 16, 2020

Article in press: December 16, 2020

Published online: January 7, 2021

Processing time: 80 Days and 13.3 Hours

Gastric gastrinoma and spontaneous tumor regression are both very rarely encountered. We report the first case of spontaneous regression of gastric gastrinoma.

A 37-year-old man with a 9-year history of chronic abdominal pain was referred for evaluation of an 8 cm mass in the lesser omentum discovered incidentally on abdominal computed tomography. The tumor was diagnosed as grade 2 neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN) on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a 7 mm red polypoid lesion with central depression in the gastric antrum, also confirmed to be a grade 2 NEN. Laparoscopic removal of the abdominal mass confirmed it to be a metastatic gastrinoma lesion. The gastric lesion was subsequently diagnosed as primary gastric gastrinoma. Three months later, the gastric lesion had disappeared without treatment. The patient remains symptom-free with normal fasting serum gastrin and no recurrence of gastrinoma during 36 mo of follow-up.

Gastric gastrinoma may arise as a polypoid lesion in the gastric antrum. Spontaneous regression can rarely occur after biopsy.

Core Tip: Gastrinoma is a functional neuroendocrine tumor which can cause refractory gastrointestinal symptoms. We present a rare case of gastrinoma originating in the stomach, with metastasis to the lesser omentum. Tumors including neuroendocrine tumors are rarely known to regress spontaneously following biopsy or surgical insult. This is the first report of spontaneous regression of a gastric gastrinoma. We also review the literature on gastric gastrinoma, gastrinoma arising in the lesser omentum, and spontaneous regression of gastrinomas and other neuroendocrine tumors.

- Citation: Okamoto T, Yoshimoto T, Ohike N, Fujikawa A, Kanie T, Fukuda K. Spontaneous regression of gastric gastrinoma after resection of metastases to the lesser omentum: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(1): 129-142

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i1/129.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i1.129

Gastrinoma is a type of neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN) with high malignant potential. It is known to cause Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES), a state of gastrin hypersecretion causing peptic ulcers in over 90% of affected cases[1]. The annual incidence has been reported at 0.5-2 per million. About 25% are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 1, while the remainder are sporadic[2]. Most arise in the gastrinoma triangle, an area with borders formed by the porta hepatis, duodenum, and pancreatic head[1]. Duodenal and pancreatic gastrinomas make up over 80% of all gastrinomas; other potential sites for primary lesions include the liver, biliary tree, ovary, kidney, jejunum, greater and lesser omentum, heart, and stomach[2-4].

Gastric NENs have an annual incidence of 2-5 per 100000 persons and account for 0.3%-1.8% of all gastric tumors, 5.6%-7.4% of NENs, and 6.9%-8.7% of all digestive NENs[5-8]. A large majority arise from enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells which are stimulated by gastrin and secrete histamines[9-11]. As ECL cells are distributed in the gastric fundus and corpus, antral NENs are rare and originate from G-cells (which produce gastrin), D-cells (somatostatin) and enterochromaffin cells (serotonin).

NENs arising from ECL cells (ECLomas) are classified into 3 types based on etiology[5,6]. Type 1 is the most common and often presents with small, multiple polypoid lesions in the setting of autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Type 2 is the rarest type, accounting for 5%-6% of gastric NENs. It also commonly presents with small, multiple polypoid lesions in the fundus or body, but arises in the setting of gastrinoma or MEN type 1. Both type 1 and type 2 have high fasting serum gastrin (FSG) but type 2 has lower gastric pH and higher rates of metastasis (10%-30%). Type 3 commonly presents with large neuroendocrine carcinoma, has normal FSG, and metastatic disease is observed in a majority of cases. More recently, a fourth type involving multiple lesions associated with hypergastrinemia, endocrine cell hyperplasia, and parietal cell hypertrophy has been reported[12]. Gastric NENs originate in the deep mucosa and invade the submucosa, creating dome-like protrusions with or without central depressions when observed endoscopically[13].

Gastric gastrinomas do not fit into this framework, as they are not ECLomas. To the extent of our search, there are only 12 reports of gastric gastrinoma in the English literature[4,5,14-23]. While gastrinomas can occur sporadically or in connection with MEN type 1, all reported gastric cases in the English language are sporadic gastrinomas. There is one French report of a gastric gastrinoma associated with the latter[24].

Spontaneous regression is defined as the complete or partial disappearance of a tumor with no or inadequate treatment[25]. It is not equivalent to cure; the tumor may reappear in the same location or elsewhere in the body. While initially estimated to occur once in every 60000-100000 cases, recent studies suggest that at least partial regression may be much more common[26-28]. The frequency of spontaneous regression varies widely depending on the tumor, with a large number of reports in renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and neuroblastoma[25,26,28]. Reports in gastric NENs are scarce[29-31]. Immunological response by tumor infiltrating leukocytes such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes has been implicated as a possible explanation, while the impact of hormones, infection, diet and nutrition, toxins, genetics, and invasive procedures such as biopsies and surgery have also been suggested[26,28,32,33].

Here, we present a case of gastric gastrinoma with large metastases to the lesser omentum. The primary gastric lesion regressed spontaneously following biopsy of the gastric lesion and surgical resection of the metastatic lesion. We also review the existing literature on gastric gastrinomas, gastrinomas of the lesser omentum, and spontaneous regression of NENs.

A 37-year-old man presented to the emergency department after sudden cardio-pulmonary arrest while outdoors.

Return of spontaneous circulation was achieved due to bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and 2 electric shocks from an automated external defibrillator.

His medical history was only significant for gastric mucosal erosions diagnosed 9 years prior to admission. The patient had chronic abdominal pain and occasional reflux symptoms despite continued treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

He had never consumed alcohol or smoked cigarettes. He had no known food or drug allergies. He had also never experienced syncope or palpitations in the past.

Body temperature of 36.2 degrees Celsius, blood pressure of 139/111 mmHg, sinus tachycardia with a heart rate of 130 beats/min, and respiratory rate of 32 times/min were noted upon arrival. The patient’s eyes were open but he could not speak (Glasgow Coma Scale: E4V1M4). Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Laboratory values were significant for leukocytosis, mild increase in liver enzymes and creatinine, lactic acidosis (pH of 7.118 and lactate of 8.1 mmol/L on arterial blood gas analysis), and a severely elevated D-dimer of over 100 mcg/mL. Electrolytes were within their normal ranges. Rapid improvement was observed on serial follow-up examinations.

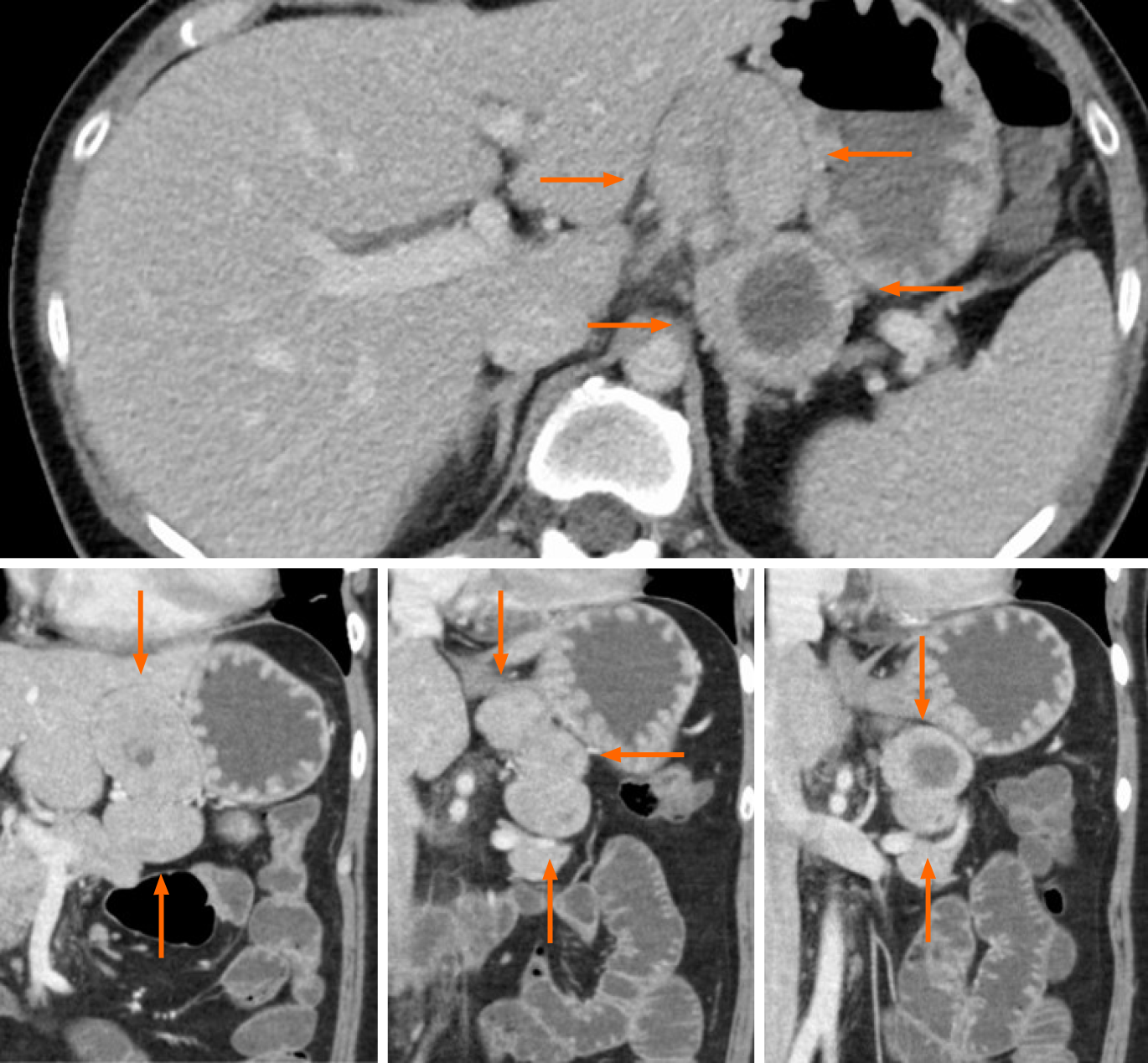

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast at admission revealed an incidental 8 cm mass in the lesser omentum (Figure 1). The mass appeared to result from the fusion of 3 similar solid tumors, of which 1 contained a non-enhancing, low-density area suggestive of necrosis or hematoma.

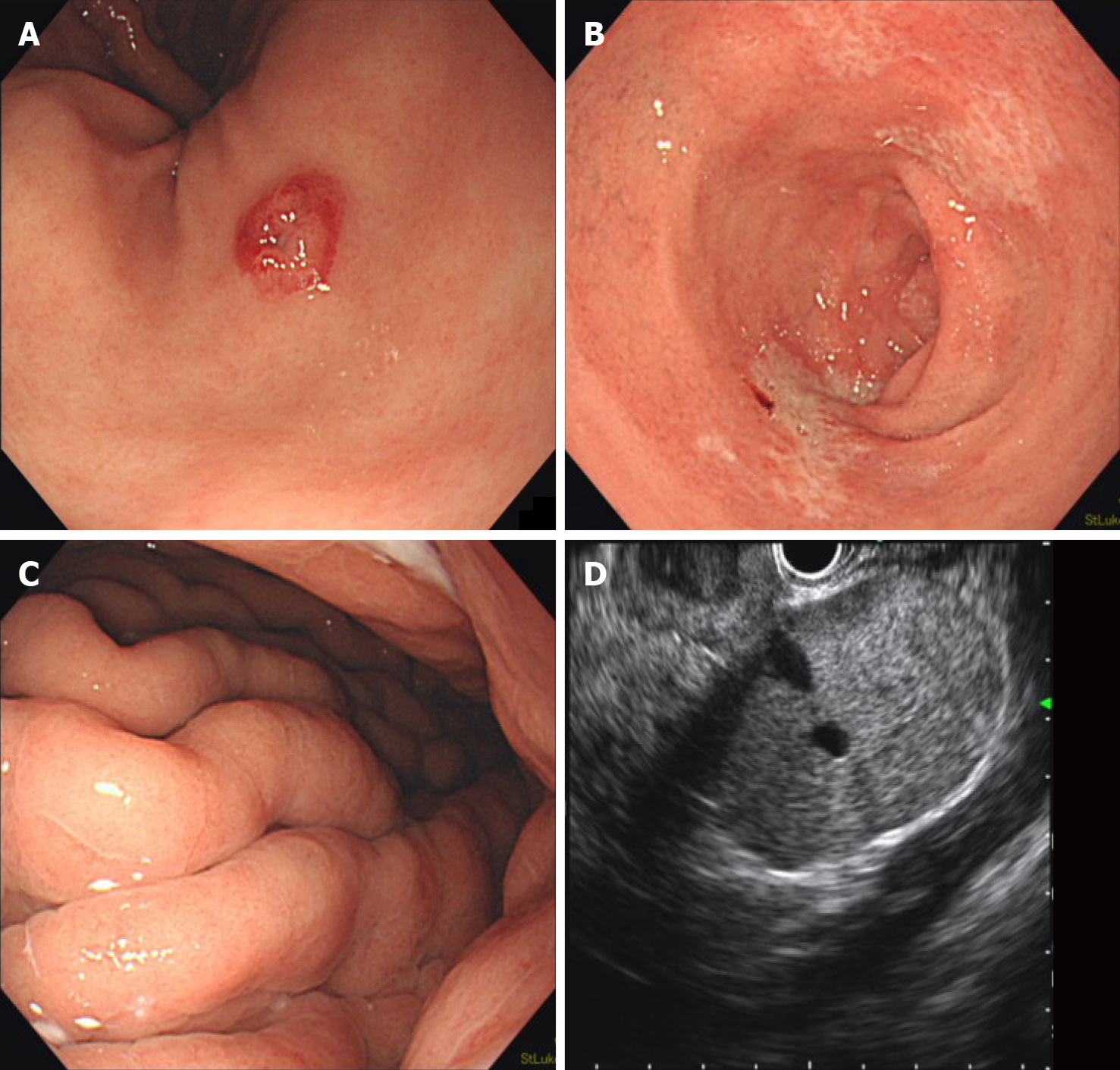

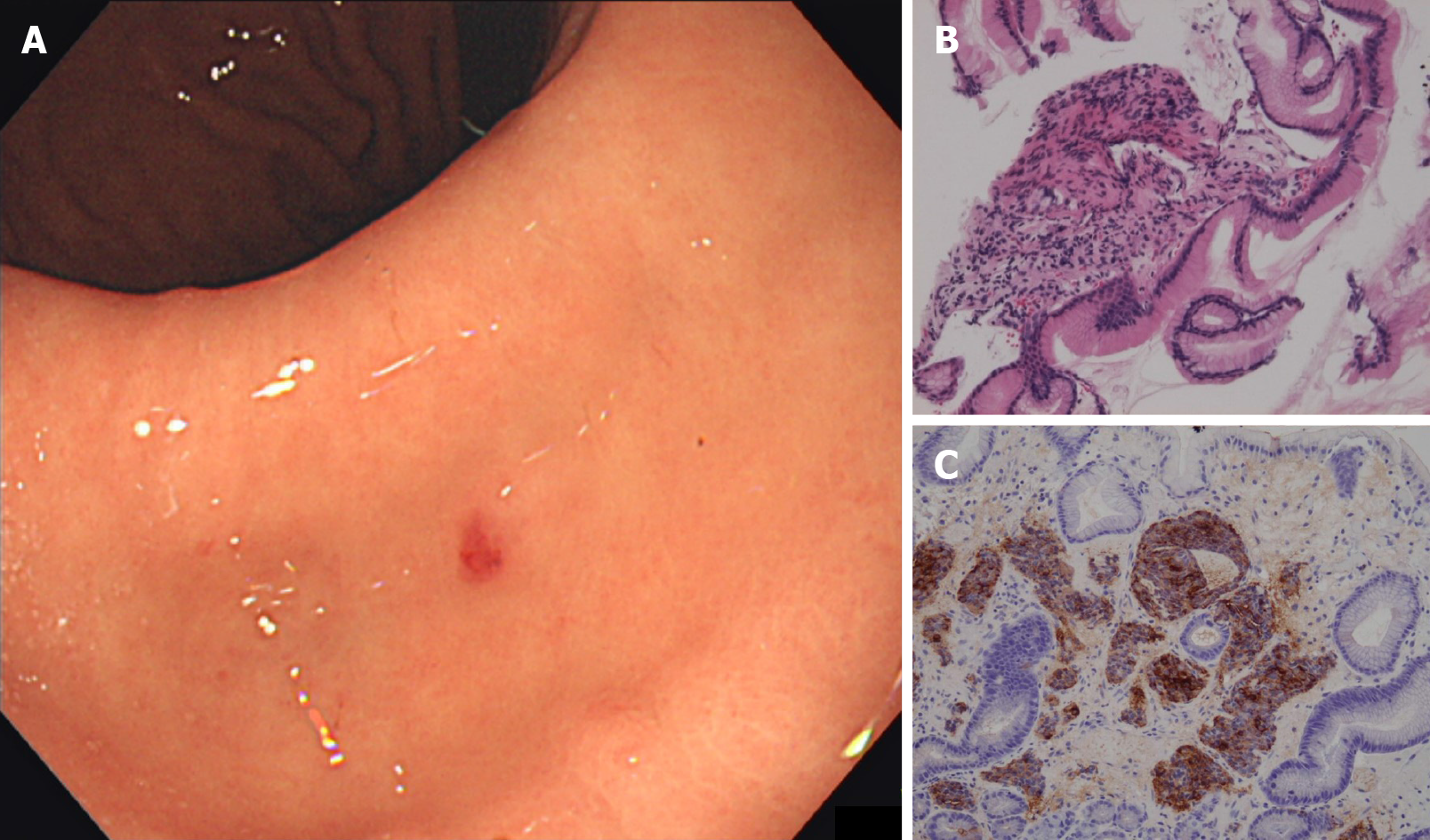

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) incidentally revealed a red, 7 mm submucosal tumor with central depression, which was biopsied (Figure 2A). Prominent gastric folds and shallow duodenal ulcers were also noted despite prolonged intravenous PPI treatment during admission (Figure 2B and C). No signs of gastroesophageal reflux disease or duodenal submucosal tumors were observed. Endoscopic ultrasound revealed 3 clearly delineated, hyperechoic masses with uniform texture, of which 1 had a hypoechoic center (Figure 2D). No pancreatic tumors were noted. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was performed. Pathology of both the gastric and lesser omentum specimens stained positive for chromogranin A and synapto-physin and were diagnosed as grade 2 NENs.

After admission, targeted temperature management was performed under total anesthesia. The patient recovered completely after 2 d, with no neurological sequelae. While coronary angiogram including various stress tests was unremarkable, electrocardiogram findings were suggestive of Brugada’s syndrome. An implantable cardiac defibrillator (EMBLEM MRI S-ICD System, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, United States) was implanted during admission.

As the gastric and omental lesions were initially assumed to be independent lesions, laparoscopic omental tumor resection with possible gastrectomy was planned. The intention was to perform endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) to treat the gastric lesion once post-operative recovery was confirmed. The patient provided informed consent for the surgery and the overall treatment plan based on an adequate understanding of the risks involved in each procedure, particularly given his post-resuscitation status.

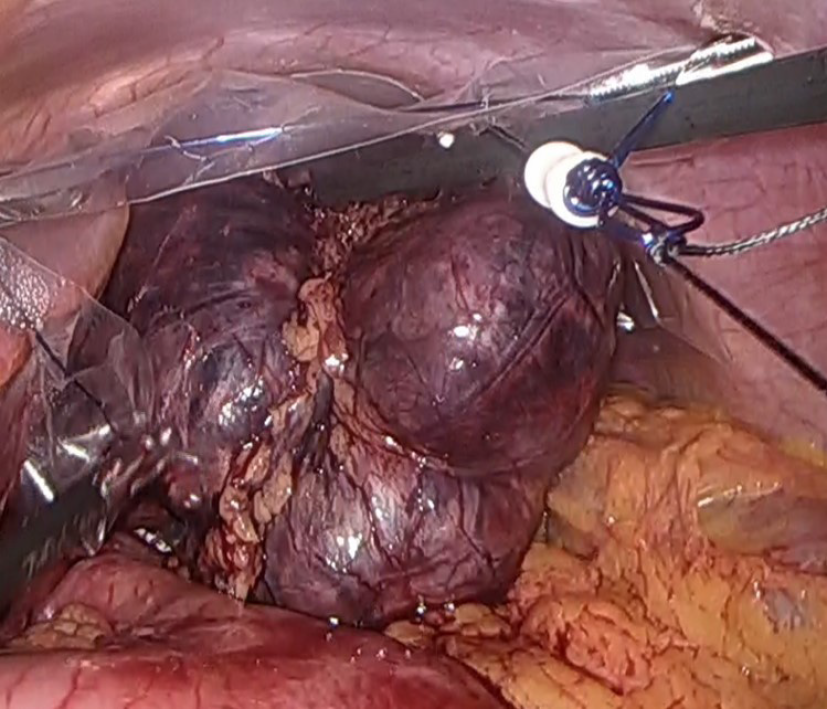

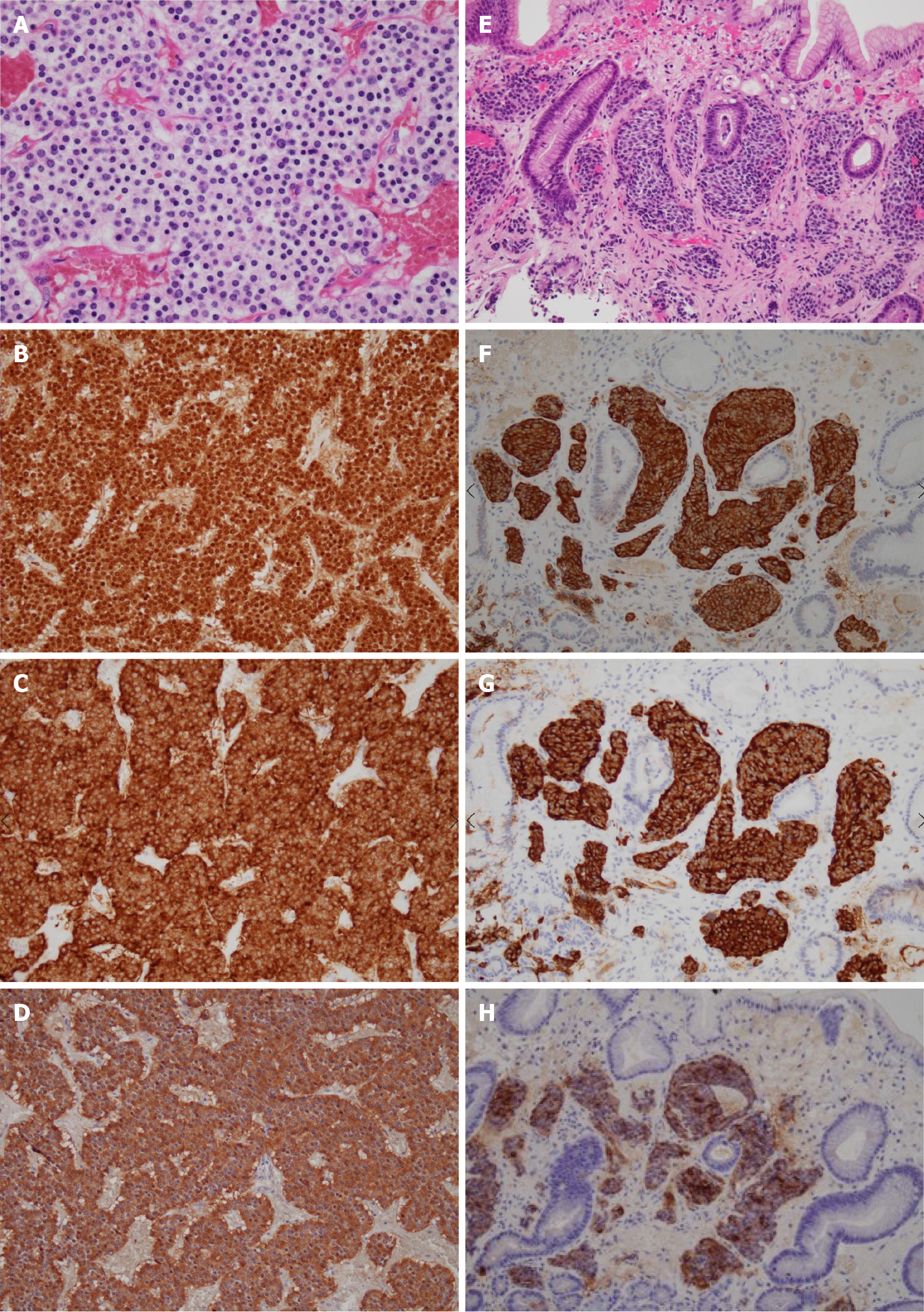

Laparoscopic surgery revealed an 83 mm × 80 mm × 37 mm mass in the lesser omentum which appeared to be formed from the fusion of 3 spherical tumors (Figure 3). No adhesion to the stomach was observed, enabling en bloc resection without partial gastrectomy. A macroscopic examination of the resected specimen revealed a brown, well-defined, encapsulated 75 mm × 40 mm solid tumor inside adipose tissue of the lesser omentum with a central hematoma. Pathology revealed nests of tumor cells characterized by small ovoid nuclei and mildly eosinophilic cytoplasms with intervening dilated capillary networks (Figure 4A). The tumor was positive for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and gastrin (Figure 4B-D). Mitotic count was less than 2 per 2 mm2 and the Ki67 index was 6%. No lymphatic or vascular invasion was noted. While initially suspected to be lymph nodes, the fused tumor was completely composed on uniform tumor cells with almost no lymphocytes except outside the encapsulated tumor. The differential at the time included primary gastrinoma of lesser omentum lymph node, lymph node metastasis from primary gastric or undetected duodenal gastrinoma, and tumor-forming hematogenous spread of gastrinoma. While the gastric lesion had not been resected, the Tumor-Node-Metastasis staging was clinically considered to be T1N1M0, stage III (Union for International Cancer Control, 8th edition) assuming the lesion was a locoregional lymph node metastasis from a gastric NEN primary.

After the surgery, results of the pre-operative FSG test returned and showed marked elevation (41100 pg/mL without discontinuation of PPIs; reference range: 37-172 pg/mL). Pathology of the stomach biopsy was re-evaluated by an expert pathologist specializing in gastrointestinal tumors and was found to have a striking resemblance to the resected lesser omentum mass (Figure 4E-G). Strong immunoreactivity with gastrin was also confirmed for the first time (Figure 4H).

The patient denied a family history of MEN type 1, of pituitary, parathyroid, or pancreatic tumors, or of peptic ulcers. Gastric pH was not evaluated as the primary cardiology team believed PPIs should not be withheld for testing. Calcium, parathyroid hormone, vitamin B12, and thyroid function tests were within their normal ranges. Parietal cell and intrinsic factor antibodies and Helicobacter pylori antibodies were negative. Brain, neck, and abdominal imaging showed no pituitary, parathyroid, or pancreatic tumors.

As a result, the patient was diagnosed with sporadic gastric gastrinoma with metastases to the lesser omentum.

In part due to stress from a long hospital stay, the patient left the hospital against medical advice after surgery.

He voluntarily returned for follow-up EGD 3 mo later to be re-evaluated before a possible distal gastrectomy. However, the gastric gastrinoma had reduced to a red dot with no visible elevation and was barely identifiable (Figure 5A). Biopsy of the lesion was negative for tumor, with only regenerative and fibrous changes (Figure 5B). Chromogranin A and synaptophysin stains were also negative (Figure 5C). In addition, duodenal ulcers had healed completely, allowing the patient to discontinue PPIs for the first time in 9 years. The prominent gastric folds observed in the gastric corpus had also normalized. FSG decreased dramatically to the normal range (167 pg/mL) and somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy (Octreoscan) showed no focal uptake throughout the body, including the stomach and lesser omentum. Based on a careful discussion of the risks involved, the patient decided to forgo surgery and opted for close observation.

Subsequent endoscopic findings have remained unchanged, FSG has remained within the normal range, and CT and scintigraphy have shown no recurrence of gastrinoma during 36 mo of follow-up. The patient remains asymptomatic without PPIs. No shocks from his implantable cardiac defibrillator have been triggered to date.

G-cells are neuroendocrine cells which secrete gastrin. G-cells are stimulated by vagal stimulation via gastrin-releasing peptide, producing gastrin which in turn stimulate ECL cells to produce histamines. While G-cell NENs are strongly positive for the gastrin stain, they are not considered gastrinomas unless they present with symptoms consistent with ZES; gastrinoma is a clinical diagnosis[4-6]. Primary gastric gastrinoma is a rare clinical entity, even though most G-cells in the human body residing in the gastric antrum. La Rosa et al[11] found only 1 case of gastric gastrinoma among 8 antral G-cell NENs and among 209 gastric NENs.

Huang et al[14] reported an exceptionally high rate of gastrinomas among NENs at their institution: 20 cases of gastrinoma, of which 9 were gastric gastrinomas, out of 109 upper gastrointestinal NENs studied. However, they state in their discussion that type 1 and type 2 gastric NENs were considered gastrinomas. Their report appears to be focused on NENs (ECLomas) induced by hypergastrinemia instead of gastrin-producing primary NENs, which is our topic of discussion.

We conducted a PubMed search using the search terms “gastrinoma AND (stomach OR gastric)” and investigated all sources cited in each relevant report. We found 12 reports in the English language (excluding abstracts), mostly from the twentieth century (Table 1)[4,5,15-23]. Among the 13 reports including our case, there was a male preponderance (83%). Ages varied broadly, from 11 to 91 years of age. Most had a long history of abdominal symptoms and all lesions with specified locations were found in the distal half of the stomach, mainly in the antrum. Surgery was generally the treatment of choice, after which FSG normalized in a majority of cases. Lymph nodes and the liver were the most common sites for metastases.

| Case | Ref. | Year | Age | Gender | Symptoms | Symptom duration (yr) | History of peptic ulcer | Location | Size (mm) | Metastases | Gastrin before surgery (pg/mL) | Gastrin after surgery (pg/mL) | Treatment | Follow-up (mo) | Recurrence |

| 1 | Royston et al[16] | 1972 | 65 | M | Abdominal pain | 14 | + | Whole stomach | Large | - | > 1000 | Undetectable | Total gastrectomy | 15 | - |

| 2 | Larsson et al[17] | 1973 | 65 | M | Abdominal pain, hematemesis | 10 | + | Antro-pylorus | 10 | - | NA | NA | Gastrectomy | 12 | - |

| 3 | Bhagavan et al[18] | 1974 | 11 | M | Acute peritonitis | 0 | - | Antrum (multiple) | Micro-scopic | - | > 1000 | 11000 | Total gastrectomy | 12 | NA |

| 4 | Russo et al[19] | 1980 | 51 | F | Dyspepsia | 7 | - | Antrum-body junction | 10 | - | 265 | < 100 | Polypectomy, antrectomy + splenectomy | 36 | - |

| 5 | Thompson et al[20] | 1985 | 19 | M | NA | 3 | + | Antrum | 20 | Liver | 3000-4000 | Normal | Total gastrectomy + segmental hepatectomy | NA | - |

| 6 | Liu et al[21] | 1989 | 50 | M | Pain, diarrhea, vomiting, weight loss | 1.5 | + | Antrum | < 10 | Lymph node | 1100-3000 | 153 | Total gastrectomy | 36 | + |

| 7 | Liu et al[21] | 1989 | 36 | F | Pain, diarrhea, vomiting, weight loss | 3.5 | + | Lower body/antrum-body junction (multiple) | 60 | Lymph node, liver | 518 | 4900 | Subtotal gastrectomy | 29 (dead) | NA |

| 8 | Werbel et al[22] | 1989 | 72 | M | Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss | 8 | + | Antrum | 15 | - | 340 | 40 | Antrectomy + vagotomy | 12 | - |

| 9 | Rindi et al[5] | 1993 | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | Pylorus | 20 | - | Elevated | Normal | Distal gastrectomy | NA | - |

| 10 | Wu et al[4] | 1997 | 40 | M | NA | NA | NA | Pylorus | NA | - | 373 | 250 | Enucleation | 140 | + |

| 11 | de Leval et al[23] | 2002 | 91 | M | Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss | 4 | + | Antrum | 55 | Lymph node, liver | 3500 | NA | None | 0 (dead) | NA |

| 12 | Tartaglia et al[15] | 2005 | 37 | M | Abdominal pain, nausea | 8 | + | Angulus | 7 | Hepatogastric ligament | 420 | 95 | Endoscopic resection, subtotal gastrectomy + left hepatic lobectomy, lanreotide | 72 | + |

| 13 | Our case | 2020 | 37 | M | Abdominal pain | 9 | + | Antrum | 7 | Lesser omentum | 41100 | 167 | Tumor resection | 30 | - |

Treatment for gastric gastrinoma has not been elucidated due to its rarity. Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) both recommend radical resection with lymph node sampling for duodenal and pancreatic gastrinomas[7,34]. While both NCCN and ENETS guidelines permit endoscopic resection for certain types of small gastric NENs, radical resection with lymph node sampling should be performed for gastric gastrinomas due to the potential for metastases. Although some authors suggest a role for endoscopic resection of gastric gastrinomas[35], our preferred approach is open surgery with intraoperative digital and ultrasound exploration to investigate undetected duodenal primaries. In the present case, laparoscopy was performed instead of open surgery as the diagnosis of gastrinoma was not reached before surgery.

A gastrinoma work-up is generally considered when encountering NENs in the gastric fundus or corpus. We propose that gastric gastrinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis for a NEN in the gastric antrum, particularly when accompanied by peptic ulcers and prominent gastric folds.

Before reaching the final diagnosis of primary gastric gastrinoma with metastasis to the lesser omentum, we considered several other possibilities for the relationship between the gastric and lesser omentum lesions.

Primary omental gastrinoma with gastric NEN from ectopic ECL cells: While ECL cells generally do not exist in the gastric antrum, type 2 antral NENs arising from ectopic ECL cells were observed in at least 2 of 4 antral NEN cases in one report[36]. However, the positive gastrin stain in our case supports a G-cell origin.

Primary gastrinoma of the lesser omentum with gastric metastasis: We initially entertained the possibility that the large lesser omentum lesion was the primary site. Primary tumors of the lesser omentum are rare. Most are benign tumors such as lymphangiomas and hemangiomas, with isolated reports of gastrointestinal stroma tumors and malignancies such as soft tissue sarcoma, lymphoma, and small cell carcinoma[37-40]. There are 5 reports of primary gastrinoma of the lesser omentum (Table 2)[41-44]. Four cases were relatively young males (average age: 26.3 years) including 2 teenagers, while the fifth was an elderly woman. All had solitary tumors and none had any evidence of MEN type 1. Tumors in most cases exceeded 4 cm but had no metastases. Normalization of serum gastrin and recurrence-free status was achieved in all cases. Tumor resection without gastrectomy was possible in 3 cases, while total gastrectomy was performed in 2 cases. These is also one report of primary gastrinoma of the greater omentum in which serum gastrin similarly normalized after surgery and no recurrence was observed[45].

| Case | Ref. | Year | Age | Gender | Symptoms | Size (mm) | Gastrin before surgery (pg/mL) | Gastrin after surgery (pg/mL) | Treatment | Follow-up (mo) | Recurrence |

| 1 | Wolfe et al[41] | 1982 | 51 | M | Recurrent duodenal ulcer | NA | 753 | 112 | Total gastrectomy | 60 | - |

| 2 | Wolfe et al[41] | 1982 | 15 | M | Hematemesis, abdominal pain, diarrhea | 25 | 455 | 41 | Tumor resection | 12 | - |

| 3 | Kohyama et al[42] | 2007 | 74 | F | Abdominal pain | 40 | 1850 | 118 | Resection of remnant stomach with tumor | 24 | - |

| 4 | Chang et al[43] | 2010 | 13 | M | Abdominal pain, diarrhea | 45 × 37 | 1263 | Normal | Tumor resection | 36 | - |

| 5 | Labidi et al[44] | 2018 | 26 | M | Melena, abdominal pain | 50 × 40 | 306 | Normal | Tumor resection | 6 | - |

There is no known method of determining whether the gastric lesion or the omental lesion was the primary gastrinoma. However, both sub-centimeter duodenal gastrinomas and sub-centimeter gastric NENs have been reported to metastasize[11,15]. To the extent of our search, there are no reports of gastrinomas metastasizing to the stomach. It therefore appears natural to consider the gastric lesion as the primary site.

Primary lymph node gastrinoma with gastric metastasis: The existence of primary lymph node gastrinoma remains in dispute among experts. Sub-centimeter duodenal primaries commonly exhibit distant metastases and may be undetected despite careful evaluation, including autopsy. In a study of 176 ZES patients, lymph nodes were the only lesions discovered initially in 45 cases[46]. While small duodenal gastrinomas had been missed in several cases, 26 appeared to be completely cured after surgical resection of the involved lymph node. None of these cases arose in the omentum.

Furthermore, primary lymph node gastrinoma is currently diagnosed when diagnostic criteria for gastrinoma are met without any confirmed lesions other than lymph nodes and their resection leads to normalization of FSG and other laboratory or radiological findings suggestive of gastrinoma. This definition fails to account for spontaneous regression of an undetected primary after surgery, discussed below.

Gastric and omental metastases from undiscovered primary duodenal tumor: Most gastrinomas arise in the duodenum and small duodenal gastrinomas undetected by endoscopic or imaging studies are known to metastasize. As surgery was not performed in our patient, this possibility is the most difficult to rule out. There is no way to confirm whether or not spontaneous regression, which occurred in the stomach, also occurred in the duodenum. However, as stated previously, we found no reports of gastrinoma metastasizing to the stomach.

Gastric NEN triggered by chronic PPI use: Chronic PPI use is widely known to cause ECL cell hyperplasia as well as hypergastrinemia, albeit at mild levels of approximately 1-3 times the upper limit of normal which generally plateaus after 1-2 years. A systematic review of 1920 patients on PPIs found no found gastric NENs[47]. On the other hand, a single center study reported that 3 of 31 gastric NENs arose in patients with long-term PPI use in the absence of autoimmune atrophic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, or ZES. ECL hyperplasia was not observed in 1 of the 3 cases, while another was a 6 mm, grade 2 NEN with normal FSG[48]. A study of 66 gastric NENs in long-term PPI users reported that 9% of NENs arose in the antrum or pylorus, but did not specify whether these were ECL-cell NENs[49]. In any event, the strongly positive gastrin stain and strong resemblance to the omental lesion makes this an unlikely explanation in our case.

Multicentric or incidental simultaneous occurrence of gastric and omental NENs: Simultaneous multicentric occurrence of NENs is another possibility. The negative tests for MEN type 1 and the strong pathological resemblance between the gastric primary and omental metastasis does not allow us to rule this out completely. Additional molecular genetic testing, not available at our institution, may shed light on this possibility[50].

It is also possible for sporadic NENs in 2 separate organs to be discovered incidentally at the same time. This premature assumption led to a delay in the diagnosis in our patient. There are no reports on this phenomenon and other possibilities should be considered first, particularly in young patients with no apparent risk factors for NEN development. Had gastrinoma been suspected in advance, open laparotomy with digital and ultrasound exploration would have been selected over laparoscopy. The pathological resemblance between the 2 lesions was too strong for them to be considered unrelated lesions.

Complete and partial spontaneous regressions of NENs have been observed in various organs. Most reports involve Merkel cell carcinomas and neuroblastomas, which are neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin and sympathetic nervous system, respectively[51,52]. Isolated cases of spontaneous regression of NENs in the pancreas, lung, bile duct, thymus, and pelvis have been reported, as well as in metastatic disease[53-58]. Biopsy, surgery for another condition, and pregnancy have been suggested as possible triggers[54-56].

Focusing on this placebo arms of randomized controlled trials conducted from 1980 to 2014, Ghatalia et al[27] investigated spontaneous regression in various solid tumors including 2 trials relating to pancreatic NENs. Partial spontaneous regression was observed in 4 of 252 patients receiving placebo, for an overall response ratio (ORR) of 1.6%. Amoroso expanded this idea to include 5 trials on NENs and found an ORR of 1.52% among 531 patients receiving placebo[53]. The authors also found minor response, defined as a 10%-30% reduction in tumor size from baseline, in almost 6% of NEN patients receiving placebo. While no complete spontaneous regressions were observed in these studies, partial spontaneous regressions may not be as rare as once believed.

Spontaneous regression of metastatic gastrinomas after biopsy and/or surgery was reported as far back as the 1960s. Disappearance of biopsy-proven liver and/or lung metastases on imaging or during second-look operations were observed in 2 out of 44 gastrinoma patients in one study and 4 out of 267 metastatic reports in another, all following total gastrectomy[59,60]. There are also sparse reports of spontaneous regression of gastric NENs. An Indian report detailed the complete spontaneous regression of an 11 cm gastric NEN after exploratory laparotomy[29]. Another report from Hong Kong found no residual tumor in the gastrectomy specimen after biopsy revealed a 4 cm high-grade large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma in the gastric cardia[30]. Complete spontaneous regression was observed in both cases after either biopsy or surgical insult. Three cases of autoimmune atrophic gastritis in which multiple small gastric carcinoids regressed spontaneously during follow-up have also been reported[31].

In our case, we believe that complete spontaneous regression was achieved based on normalized FSG, cure of peptic ulcers, no signs of recurrence on imaging, and the negative biopsy of the gastric lesion. However, the biopsy was limited to the mucosal layer and remnants of tumor in the submucosal layer cannot be completely ruled out without surgery or ESD. While the patient did not consent to such additional treatment, at least a partial spontaneous regression was clearly achieved. We speculate biopsy of the primary lesion and subsequent surgery triggered the spontaneous regression.

To the extent of our search, we could not find any relationship between ZES and Brugada’s syndrome, which was the cause of our patient’s cardiopulmonary arrest. While cardiopulmonary arrest due to carcinoid syndrome has been reported, there were no clinical manifestations to raise any suspicion of this rare event[61]. We suspect that the gastrinoma was unrelated to the cardiopulmonary arrest.

In conclusion, we report a case of gastric gastrinoma which regressed spontaneously after biopsy and resection of a metastatic lesion in the lesser omentum. ZES can be left undetected for years and should be suspected in longstanding reflux disease or abdominal pain refractory to PPIs. NENs in the antrum should alert the physician for possible gastrinoma as well as NENs of other non-ECL cell origins. Further research is required to further clarify the mechanisms behind spontaneous regression and to determine the characteristics of lesions or patients who may experience this extraordinary phenomenon. Such research may contribute to the discovery of new immunotherapies and to the reduction of unnecessary surgeries.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Japanese Society of Gastroenterology, No. 055165; Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society, No. 36153140.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sun Q S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Brandi ML, de Herder WW, Kaltsas G, Komminoth P, Scoazec JY, Salazar R, Sauvanet A, Kianmanesh R; Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: functional pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:98-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 465] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83:43-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jensen RT, Niederle B, Mitry E, Ramage JK, Steinmuller T, Lewington V, Scarpa A, Sundin A, Perren A, Gross D, O'Connor JM, Pauwels S, Kloppel G; Frascati Consensus Conference; European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Gastrinoma (duodenal and pancreatic). Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu PC, Alexander HR, Bartlett DL, Doppman JL, Fraker DL, Norton JA, Gibril F, Fogt F, Jensen RT. A prospective analysis of the frequency, location, and curability of ectopic (nonpancreaticoduodenal, nonnodal) gastrinoma. Surgery. 1997;122:1176-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rindi G, Luinetti O, Cornaggia M, Capella C, Solcia E. Three subtypes of gastric argyrophil carcinoid and the gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:994-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rindi G, Klimstra DS, Abedi-Ardekani B, Asa SL, Bosman FT, Brambilla E, Busam KJ, de Krijger RR, Dietel M, El-Naggar AK, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Klöppel G, McCluggage WG, Moch H, Ohgaki H, Rakha EA, Reed NS, Rous BA, Sasano H, Scarpa A, Scoazec JY, Travis WD, Tallini G, Trouillas J, van Krieken JH, Cree IA. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1770-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 706] [Article Influence: 100.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Delle Fave G, O'Toole D, Sundin A, Taal B, Ferolla P, Ramage JK, Ferone D, Ito T, Weber W, Zheng-Pei Z, De Herder WW, Pascher A, Ruszniewski P; Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Gastroduodenal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Alexandraki KI, Angelousi A, Chatzellis E, Sougioultzis S, Kaltsas G. Gastric Carcinoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018;47:645-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | WHO of Tumours Editorial Board. Digestive system tumors. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 5th ed. 2019; 1: 104-109. Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/Digestive-System-Tumours-2019. |

| 10. | La Rosa S, Vanoli A. Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms and related precursor lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:938-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | La Rosa S, Inzani F, Vanoli A, Klersy C, Dainese L, Rindi G, Capella C, Bordi C, Solcia E. Histologic characterization and improved prognostic evaluation of 209 gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1373-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Ooi A, Ota M, Katsuda S, Nakanishi I, Sugawara H, Takahashi I. An Unusual Case of Multiple Gastric Carcinoids Associated with Diffuse Endocrine Cell Hyperplasia and Parietal Cell Hypertrophy. Endocr Pathol. 1995;6:229-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sato Y, Hashimoto S, Mizuno K, Takeuchi M, Terai S. Management of gastric and duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6817-6828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 14. | Huang SF, Kuo IM, Lee CW, Pan KT, Chen TC, Lin CJ, Hwang TL, Yu MC. Comparison study of gastrinomas between gastric and non-gastric origins. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tartaglia A, Vezzadini C, Bianchini S, Vezzadini P. Gastrinoma of the stomach: a case report. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;35:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Royston CM, Brew DS, Garnham JR, Stagg BH, Polak J. The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome due to an infiltrating tumour of the stomach. Gut. 1972;13:638-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Larsson LI, Ljungberg O, Sundler F, Håkanson R, Svensson SO, Rehfeld J, Stadil R, Holst J. Antor-pyloric gastrinoma associated with pancreatic nesidioblastosis and proliferation of islets. Virchows Arch A Pathol Pathol Anat. 1973;360:305-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bhagavan BS, Hofkin GA, Woel GM, Koss LG. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ultrastructural and histochemical observations in a child with endocrine tumorlets of gastric antrum. Arch Pathol. 1974;98:217-222. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Russo A, Buffa R, Grasso G, Giannone G, Sanfilippo G, Sessa F, Solcia E. Gastric gastrinoma and diffuse G cell hyperplasia associated with chronic atrophic gastritis. Endoscopic detection and removal. Digestion. 1980;20:416-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thompson NW, Vinik AI, Eckhauser FE, Strodel WE. Extrapancreatic gastrinomas. Surgery. 1985;98:1113-1120. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Liu TH, Zhong SX, Chen YF, Lin Y, Chen J, Li DC, Wang DT, Gu CF, Yie SF. Gastric gastrinoma. Chin Med J (Engl). 1989;102:774-782. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Werbel GB, Nelson SP, Robinson PG, Anastasi J, Joehl RJ, Rege RV. A foregut carcinoid tumor causing Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Arch Surg. 1989;124:381-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | de Leval L, Hardy N, Deprez M, Delwaide J, Belaïche J, Boniver J. Gastric collision between a papillotubular adenocarcinoma and a gastrinoma in a patient with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:462-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Buyse S, Charachon A, Petit T, Marmuse JP, Mignon M, Soule JC. [The gastric antrum: a rare primitive location of a gastrinoma within a type I multiple endocrine neoplasia]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:625-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | COLE WH, EVERSON TC. Spontaneous regression of cancer: preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1956;144:366-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ghatalia P, Morgan CJ, Sonpavde G. Meta-analysis of regression of advanced solid tumors in patients receiving placebo or no anti-cancer therapy in prospective trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;98:122-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Challis GB, Stam HJ. The spontaneous regression of cancer. A review of cases from 1900 to 1987. Acta Oncol. 1990;29:545-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sawant PD, Nanivadekar SA, Shroff CP, Srinivas A, Dewoolkar VV. Spontaneous regression of large gastric carcinoid. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1989;8:289-290. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Ip YT, Pong WM, Kao SS, Chan JK. Spontaneous complete regression of gastric large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: mediated by cytomegalovirus-induced cross-autoimmunity? Int J Surg Pathol. 2011;19:355-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Harvey RF. Spontaneous resolution of multifocal gastric enterochromaffin-like cell carcinoid tumours. Lancet. 1988;1:821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bodey B. Spontaneous regression of neoplasms: new possibilities for immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2002;2:459-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Abdelrazeq AS. Spontaneous regression of colorectal cancer: a review of cases from 1900 to 2005. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:727-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors Version 2.2020 – July 24, 2020. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/. |

| 35. | Shao QQ, Zhao BB, Dong LB, Cao HT, Wang WB. Surgical management of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Classical considerations and current controversies. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4673-4681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bordi C, Corleto VD, Azzoni C, Pizzi S, Ferraro G, Gibril F, Delle Fave G, Jensen RT. The antral mucosa as a new site for endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndromes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2236-2242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ninomiya S, Hiroishi K, Shiromizu A, Ueda Y, Shiraishi N, Inomata M, Arita T. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the lesser omentum: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjz035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Feng JF, Guo YH, Chen WY, Chen DF, Liu J. Primary small cell carcinoma of the lesser omentum. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2012;28:115-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wang B, Ren KW, Yang YC, Wan DL, Li XJ, Zhai ZL, Zhang LL, Zheng SS. Carcinosarcoma of the Lesser Omentum: A Unique Case Report and Literature Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Onodera H, Maetani S, Imamura M, Hayashi K, Nakayama T, Aoki T. [A case of a huge malignant lymphoma in the lesser omentum showing a long-term survival after combined treatment of surgery and VEP-THP chemotherapy]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1994;21:689-692. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Wolfe MM, Alexander RW, McGuigan JE. Extrapancreatic, extraintestinal gastrinoma: effective treatment by surgery. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1533-1536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kohyama A, Shibata C, Funayama Y, Fukushima K, Takahashi K, Ueno T, Kobayashi T, Kinouchi M, Sasaki I, Moriya T. Primary Gastrinoma in the Lesser Omentum: A Case Report. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2007;40:1582-1586. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Chang FY, Liao KY, Wu L, Lin SP, Lai YT, Liu CS, Tsay SH, Wu TC. An uncommon cause of abdominal pain and diarrhea-gastrinoma in an adolescent. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:355-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Labidi A, Hamdi S, Ben Othman A, Chelly B, Daghfous A, Fekih M. A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Primary gastrinoma of the lesser omentum. Presse Med. 2018;47:913-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Pisegna JR, Norton JA, Slimak GG, Metz DC, Maton PN, Gardner JD, Jensen RT. Effects of curative gastrinoma resection on gastric secretory function and antisecretory drug requirement in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:767-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Norton JA, Alexander HR, Fraker DL, Venzon DJ, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Possible primary lymph node gastrinoma: occurrence, natural history, and predictive factors: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2003;237:650-7; discussion 657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Lundell L, Vieth M, Gibson F, Nagy P, Kahrilas PJ. Systematic review: the effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor use on serum gastrin levels and gastric histology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:649-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cavalcoli F, Zilli A, Conte D, Ciafardini C, Massironi S. Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms and proton pump inhibitors: fact or coincidence? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1397-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 49. | Trinh VQ, Shi C, Ma C. Gastric neuroendocrine tumours from long-term proton pump inhibitor users are indolent tumours with good prognosis. Histopathology. 2020;77:865-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ahmadi Moghaddam P, Cornejo KM, Hutchinson L, Tomaszewicz K, Dresser K, Deng A, OʼDonnell P. Complete Spontaneous Regression of Merkel Cell Carcinoma After Biopsy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:e154-e158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Wang B, Xia CY, Lau WY, Lu XY, Dong H, Yu WL, Jin GZ, Cong WM, Wu MC. Determination of clonal origin of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma for personalized therapy and outcomes evaluation: a new strategy for hepatic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:1054-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | De Bernardi B, Gerrard M, Boni L, Rubie H, Cañete A, Di Cataldo A, Castel V, Forjaz de Lacerda A, Ladenstein R, Ruud E, Brichard B, Couturier J, Ellershaw C, Munzer C, Bruzzi P, Michon J, Pearson AD. Excellent outcome with reduced treatment for infants with disseminated neuroblastoma without MYCN gene amplification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1034-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Amoroso V, Agazzi GM, Roca E, Fazio N, Mosca A, Ravanelli M, Spada F, Maroldi R, Berruti A. Regression of advanced neuroendocrine tumors among patients receiving placebo. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24:L13-L16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Venkatram S, Sinha N, Hashmi H, Niazi M, Diaz-Fuentes G. Spontaneous Regression of Endobronchial Carcinoid Tumor. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2017;24:70-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Sewpaul A, Bargiela D, James A, Johnson SJ, French JJ. Spontaneous Regression of a Carcinoid Tumor following Pregnancy. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2014;2014:481823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Rayson D, Pitot HC, Kvols LK. Regression of metastatic carcinoid tumor after valvular surgery for carcinoid heart disease. Cancer. 1997;79:605-611. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Sano I, Kuwatani M, Sugiura R, Kato S, Kawakubo K, Ueno T, Nakanishi Y, Mitsuhashi T, Hirata H, Haba S, Hirano S, Sakamoto N. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: A rare case of a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor in the bile duct with spontaneous regression diagnosed by EUS-FNA. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Kawaguchi K, Usami N, Okasaka T, Yokoi K. Multiple thymic carcinoids. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1973-1975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Delcore R, Friesen SR. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. A new look at regression of gastrinomas. Arch Surg. 1991;126:556-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Fox PS, Hofmann JW, Decosse JJ, Wilson SD. The influence of total gastrectomy on survival in malignant Zollinger-Ellison tumors. Ann Surg. 1974;180:558-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Magabe PC, Bloom AL. Sudden death from carcinoid crisis during image-guided biopsy of a lung mass. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:484-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |