Published online May 14, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i18.2232

Peer-review started: March 8, 2020

First decision: March 27, 2020

Revised: April 13, 2020

Accepted: April 29, 2020

Article in press: April 29, 2020

Published online: May 14, 2020

Processing time: 66 Days and 22.2 Hours

The conventional guidelines to obtain a safe proximal resection margin (PRM) of 5-6 cm during advanced gastric cancer (AGC) surgery are still applied by many surgeons across the world. Several recent studies have raised questions regarding the need for such extensive resection, but without reaching consensus. This study was designed to prove that the PRM distance does not affect the prognosis of patients who undergo gastrectomy for AGC.

To investigate the influence of the PRM distance on the prognosis of patients who underwent gastrectomy for AGC.

Electronic medical records of 1518 patients who underwent curative gastrectomy for AGC between June 2004 and December 2007 at Asan Medical Center, a tertiary care center in Korea, were reviewed retrospectively for the study. The demographics and clinicopathologic outcomes were compared between patients who underwent surgery with different PRM distances using one-way ANOVA and Fisher’s exact test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The influence of PRM on recurrence-free survival and overall survival were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazard analysis.

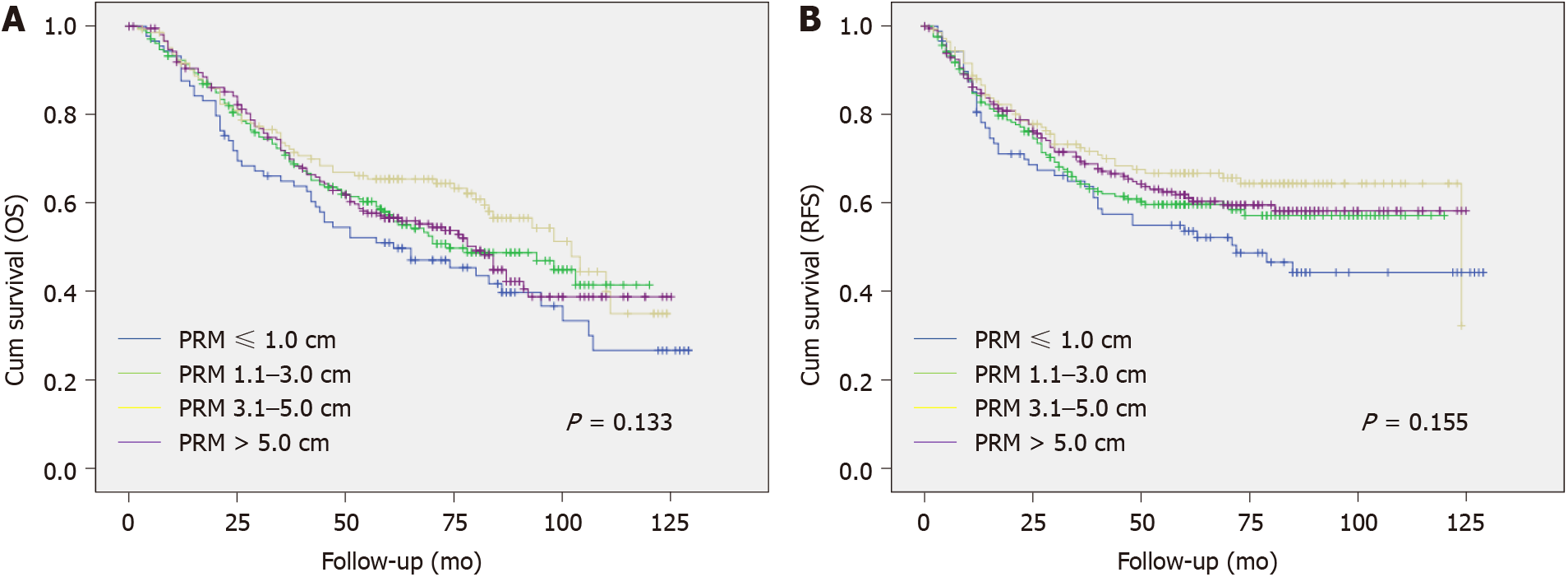

The median PRM distance was 4.8 cm and 3.5 cm in the distal gastrectomy (DG) and total gastrectomy (TG) groups, respectively. Patient cohorts in the DG and TG groups were subdivided into different groups according to the PRM distance; ≤ 1.0 cm, 1.1-3.0 cm, 3.1-5.0 cm and > 5.0 cm. The DG and TG groups showed no statistical difference in recurrence rate (23.5% vs 30.6% vs 24.0% vs 24.7%, P = 0.765) or local recurrence rate (5.9% vs 6.5% vs 8.4% vs 6.2%, P = 0.727) according to the distance of PRM. In both groups, Kalpan-Meier analysis showed no statistical difference in recurrence-free survival (P = 0.467 in DG group; P = 0.155 in TG group) or overall survival (P = 0.503 in DG group; P = 0.155 in TG group) according to the PRM distance. Multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazard model revealed that in both groups, there was no significant difference in recurrence-free survival according to the PRM distance.

The distance of PRM is not a prognostic factor for patients who undergo curative gastrectomy for AGC.

Core tip: The conventional guidelines suggest the surgeons to obtain an extensive resection margin during surgery for gastric cancer. The objective of this study was to investigate the influence of the proximal resection margin (PRM) distance on the oncologic outcomes of advanced gastric cancer patients, thus to prove the safety of the PRM distance shorter than the conventional literatures suggest. The length of the PRM did not affect the prognosis of patients who underwent a curative gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer.

- Citation: Kim A, Kim BS, Yook JH, Kim BS. Optimal proximal resection margin distance for gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(18): 2232-2246

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i18/2232.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i18.2232

Although the worldwide gastric cancer incidence has been declining over the past few decades, gastric cancer remains the third leading cause of cancer mortality[1-3] and surgery is still the mainstay curative treatment for gastric cancer patients[4]. While radical surgery with adequate resection of the stomach and lymph nodes is the prime focus of treatment, quality of life after surgery has been receiving increased attention due to improvements in the postoperative survival of gastric cancer patients. Several studies have revealed that subtotal gastrectomy leads to better nutrition and quality of life after surgery than total gastrectomy (TG)[5,6], and a recent report showed the relationship between the remnant volume of the stomach and nutritional status after surgery[7]. Thus, surgeons should consider these factors when determining the optimal extent of resection.

Bozzetti et al[8] reported that a proximal resection margin (PRM) of at least 6 cm should be obtained for tumors invading the serosa to ensure an infiltration-free margin. However, this was published back in 1982 and may not accurately reflect the current state of gastric cancer treatment where values such as function preservation, nutrition, and quality of life are emphasized. The 2014 Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines (Version 4) suggest that a gross margin of at least 3 cm should be obtained for T2 or deeper tumors with Bormann type 1 or 2, and 5 cm should be obtained for Bormann type 3 or 4 tumors[9]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends a PRM of > 4 cm for a safe microscopic margin[10]. These guidelines do not specify the clinical studies, making it difficult to assess the reliability of the suggested PRMs.

In 2014, it was reported that as long as negative margins were obtained by intraoperative frozen-section examination, PRM is not related to patient survival or local recurrence[11]. However, a 2017 study revealed that PRM is an independent prognostic factor for the overall survival (OS) of gastric cancer patients and a PRM of at least 2.1 cm should be obtained[12]. Several other studies have examined the relationship between the PRM and the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer, but the results were inconsistent[13-18], particularly for patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC).

This study is based on extensive retrospectively collected data and aims to investigate the relationship between PRM and the recurrence-free survival (RFS) or OS after surgery and thus determine the optimal PRM for patients with AGC.

Between June 2004 and December 2007, 1518 patients in total underwent total or distal gastrectomy (DG) with curative intent for AGC at the Division of Stomach Surgery in Asan Medical Center. Patients with stage IV AGC or evident gross residual tumor were observed intraoperatively and those who underwent palliative gastrectomy were not included in the study. We excluded gastroesophageal junction cancer (Siewert I or II) patients, patients with a history of previous stomach surgery, patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy and patients whose pathologic report confirmed fewer than 15 lymph nodes retrieved. Cases in which grossly positive resection margins were observed, and those where the final biopsy reports confirmed a positive resection margin were excluded. We also excluded cases without data for PRM.

To evaluate patient characteristics, we collected data on the sex, age, preoperative body mass index (BMI), history of previous operations on the stomach, medical history of hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, history of smoking, preoperative value of CEA, CA 19-9 and CA 72-4, tumor location, type of surgery (TG or DG), and type of recon-struction. Clinicopathologic outcomes included the Borrmann classification of the tumor, the number of synchronous tumors in the stomach, tumor size, depth of invasion, number of lymph nodes collected (CLN), number of positive lymph nodes (PLN), histology according to differentiation, status of lymphovascular invasion (LVi) and Perineural invasion (PNi), distance of the tumor from the PRM and distal resection margin (DRM), TNM stage based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging Manual 7th edition, recurrence status, and survival.

The extent of resection was determined according to the surgeon’s preference, primarily based on the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines. The tumor location was defined according to equally divided sections for the upper-third, middle-third, and lower-third of the stomach. For multiple cancers, the location was defined based on the most proximal tumor. The distances of the PRM and DRM were defined as the shortest distance from the most proximal or distal end to each resection line, measured on formalin-fixed surgical specimens by pathologists. Recurrence was classified as locoregional (anastomosis site, remnant stomach, gastric bed, regional lymph nodes, adjacent organ, or paraaortic lymph node), hematogenous (distant organs), peritoneal (peritoneal seeding or Krukenberg’s tumor), distant lymph nodes (extra-abdominal lymph nodes), and mixed. The main patterns of recurrence were determined based on the site at the time of diagnosis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center and the University of Ulsan College of Medicine (No. 2019-1036).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). To analyze the demographics and clinicopathologic features depending on different PRM categories, one-way ANOVA and Fisher’s exact test were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazard analysis were performed to assess the impact of PRM on RFS and OS. Any P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was reviewed by a biomedical statistician from Department of medical statistics, University of Ulsan College of Medicine.

Table 1 summarizes the patients’ baseline demographics and clinicopathologic characteristics. There were 859 patients who underwent DG and 659 patients who underwent TG. The median age at the time of operation was 60 and 57 in the two groups, respectively. In the DG group, there were 626 patients (72.9%) with tumors located in the lower third of the stomach. In the TG group, 586 (88.9%) had cancer in the upper or middle third of the stomach. After DG, anastomosis was performed using the Billroth I reconstruction method for 71.0% of patients, Billroth II for 15.9% and Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy (RYGJ) for 13.0%.

| Variables | Distal gastrectomy (n = 859) | Total gastrectomy (n = 659) |

| Age (yr; median) at operation | 60 (23-87) | 57 (22-86) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 603 (70.2) | 441 (66.9) |

| Female | 256 (29.8) | 218 (33.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2, median) | 23.2 (16.0-36.2) | 23.4 (13.4-36.0) |

| ASA | ||

| 1 | 246 (28.6) | 213 (32.3) |

| 2 | 571 (66.5) | 427 (64.8) |

| 3 | 39 (4.5) | 17 (2.6) |

| 4 | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Tumor location | ||

| Upper 1/3 | 8 (0.9) | 266 (40.4) |

| Middle 1/3 | 225 (26.2) | 320 (48.6) |

| Lower 1/3 | 626 (72.9) | 73 (11.1) |

| Reconstruction | ||

| Billroth I | 610 (71.0) | |

| Billroth II | 137 (15.9) | |

| RYGJ | 112 (13.0) | |

| RY | 659 (100.0) | |

| Bormann classification | ||

| I | 14 (1.6) | 14 (2.1) |

| II | 162 (18.9) | 66 (10.0) |

| III | 660 (76.8) | 499 (75.7) |

| IV | 23 (2.7) | 80 (12.1) |

| Tumor size (cm, median) | 5.0 (0.8-18) | 6.0 (0.7-24) |

| CLN | 27 (15-75) | 30 (15-106) |

| PLN | 2 (0-49) | 3 (0-101) |

| T stage | ||

| T2 | 288 (33.5) | 110 (16.7) |

| T3 | 370 (43.1) | 310 (47.0) |

| T4a | 195 (22.7) | 226 (34.3) |

| T4b | 6 (0.7) | 13 (2.0) |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 308 (35.9) | 203 (30.8) |

| N1 | 181 (21.1) | 110 (16.7) |

| N2 | 173 (20.1) | 128 (19.4) |

| N3a | 159 (18.5) | 133 (20.2) |

| N3b | 38 (4.4) | 85 (12.9) |

| AJCC stage | ||

| Stage I | 155 (18.0) | 66 (10.0) |

| Stage II | 336 (39.1) | 235 (35.7) |

| Stage III | 368 (42.8) | 358 (54.3) |

| PRM (cm; median) | 4.8 (0.3-17) | 3.5 (0.1-18.5) |

| DRM (cm; median) | 3.2 (0.2-19) | 9.4 (0.3-27) |

| Histology | ||

| Differentiated | 351 (40.9) | 192 (29.1) |

| Undifferentiated | 508 (59.1) | 467 (70.9) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 413 (48.1) | 360 (54.6) |

| Perineural invasion | 368 (42.8) | 344 (52.2) |

| Recurrence | 220 (25.6) | 251 (38.1) |

| Locoregional recurrence | 60 | 41 |

| Hematogenous metastasis | 74 | 83 |

| Extra-abdominal LN metastasis | 2 | 1 |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 74 | 1 |

| Mixed | 10 | 17 |

The median PRM distance was 4.8 cm and 3.5 cm in the DG and TG groups, respectively. There were 220 (25.6%) and 251 (38.1%) cases of recurrence during the follow-up period of 59 (0-127) and 58 (0-129) months in each group.

Patient cohorts in the DG and TG groups were subdivided into different groups according to the length of the PRM: ≤ 1.0 cm, 1.1-3.0 cm, 3.1-5.0 cm and > 5.0 cm. Tables 2 and 3 present the clinicopathologic factors in the different PRM subgroups. In both the DG and TG groups, there were no significant differences in age, sex, T stage, or N stage according to the PRM distance. Among patients who underwent DG, the tumor location (P < 0.001), reconstruction type (P = 0.004) and tumor size (P = 0.004) differed between the PRM subgroups. Additionally, there were more undifferentiated tumors (P = 0.023) and perineural invasion (P = 0.010) in the PRM ≤ 1 cm subgroup. In the TG group, there were statistical differences in the tumor location (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001), proportion of linitis plastica (P < 0.001), and perineural invasion (P = 0.002) between the PRM subgroups. There were no significant differences in the recurrence rate or local recurrence rate according to the PRM distance in either the DG or TG group.

| Variables | PRM (cm) | P value | |||||

| ≤ 1.0 (n = 17) | 1.1-3.0 (n = 170) | 3.1-5.0 (n = 287) | > 5.0 (n = 385) | ||||

| Age (yr)1 at operation | 59.7 ± 3.4 | 57.2 ± 1.0 | 58.2 ± 0.7 | 59.0 ± 0.6 | 0.416 | ||

| Sex | 0.279 | ||||||

| Male | 9 (52.9) | 116 (68.2) | 199 (69.3) | 279 (72.5) | |||

| Female | 8 (47.1) | 54 (31.8) | 88 (30.7) | 106 (27.5) | |||

| Tumor location | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Upper 1/3 | 1 (5.9) | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| Middle 1/3 | 9 (52.9) | 74 (43.5) | 86 (30.0) | 56 (14.5) | |||

| Lower 1/3 | 7 (41.2) | 93 (54.7) | 198 (69.0) | 328 (85.2) | |||

| Reconstruction | 0.004 | ||||||

| Billroth I | 12 (70.6) | 101 (59.4) | 218 (76.0) | 279 (72.5) | |||

| Billroth II | 3 (17.6) | 32 (18.8) | 38 (13.2) | 64 (16.6) | |||

| RYGJ | 2 (11.8) | 37 (21.8) | 31 (10.8) | 42 (10.9) | |||

| Borrmann type IV | 1 (5.9) | 6 (3.5) | 7 (2.4) | 9 (2.3) | 0.461 | ||

| Tumor size (cm)1 | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 0.004 | ||

| T stage | 0.768 | ||||||

| T2 | 5 (29.4) | 56 (32.9) | 89 (31.0) | 138 (35.8) | |||

| T3 | 7 (41.2) | 75 (44.1) | 123 (42.9) | 165 (42.9) | |||

| T4 | 5 (29.4) | 39 (22.9) | 75 (26.1) | 82 (21.3) | |||

| CLN1 | 26.6 ± 2.0 | 29.3 ± 0.8 | 29.4 ± 0.6 | 28.8 ± 0.5 | 0.612 | ||

| N stage | 0.971 | ||||||

| N0 | 5 (29.4) | 61 (35.9) | 101 (35.2) | 141 (36.6) | |||

| N1 | 2 (11.8) | 36 (21.2) | 63 (22.0) | 80 (20.8) | |||

| N2 | 4 (23.5) | 36 (21.2) | 55 (19.2) | 78 (20.3) | |||

| N3 | 6 (35.3) | 37 (21.8) | 68 (23.7) | 86 (22.3) | |||

| AJCC stage | 0.551 | ||||||

| Stage I | 4 (23.5) | 31 (18.2) | 52 (18.1) | 68 (17.7) | |||

| Stage II | 3 (17.6) | 65 (38.2) | 108 (37.6) | 160 (41.6) | |||

| Stage III | 10 (58.8) | 74 (43.5) | 127 (44.3) | 157 (40.8) | |||

| Differentiation | 0.023 | ||||||

| Differentiated | 4 (23.5) | 64 (37.6) | 105 (36.6) | 178 (46.2) | |||

| Undifferentiated | 13 (76.5) | 106 (62.4) | 182 (63.4) | 207 (53.8) | |||

| LVi | 8 (47.1) | 75 (44.1) | 142 (49.5) | 188 (48.8) | 0.706 | ||

| PNi | 9 (52.9) | 80 (47.1) | 138 (48.1) | 141 (36.6) | 0.010 | ||

| Recurrence | 4 (23.5) | 52 (30.6) | 69 (24.0) | 95 (24.7) | 0.765 | ||

| Local recurrence | 1 (5.9) | 11 (6.5) | 24 (8.4) | 24 (6.2) | 0.727 | ||

| Variables | PRM (cm) | P value | |||

| ≤ 1.0 (n = 90) | 1.1-3.0 (n = 209) | 3.1-5.0 (n = 146) | > 5.0 (n = 214) | ||

| Age (yr)1 at operation | 57.1 ± 1.2 | 55.0 ± 0.9 | 54.6 ± 0.9 | 56.3 ± 0.9 | 0.330 |

| Sex | 0.364 | ||||

| Male | 64 (71.1) | 135 (64.6) | 92 (63.0) | 150 (70.1) | |

| Female | 26 (38.9) | 74 (35.4) | 54 (37.0) | 64 (29.9) | |

| Tumor location | < 0.001 | ||||

| Upper 1/3 | 81 (90.0) | 127 (60.8) | 32 (21.9) | 26 (12.1) | |

| Middle 1/3 | 8 (8.9) | 75 (35.9) | 103 (70.5) | 134 (62.6) | |

| Lower 1/3 | 1 (1.1) | 7 (3.3) | 11 (7.5) | 54 (25.2) | |

| Borrmann type IV | 17 (18.9) | 37 (17.7) | 14 (9.6) | 12 (5.6) | < 0.001 |

| Tumor size (cm)1 | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | < 0.001 |

| T stage | 0.873 | ||||

| T2 | 14 (15.6) | 30 (14.4) | 24 (16.4) | 42 (19.6) | |

| T3 | 44 (48.9) | 100 (47.8) | 67 (45.9) | 99 (46.3) | |

| T4 | 32 (35.6) | 79 (37.8) | 55 (37.7) | 73 (34.1) | |

| CLN1 | 30.7 ± 1.1 | 33.1 ± 1.0 | 32.2 ± 1.0 | 31.0 ± 0.7 | 0.216 |

| N stage | 0.495 | ||||

| N0 | 23 (25.6) | 74 (35.4) | 47 (32.2) | 59 (27.6) | |

| N1 | 14 (15.6) | 35 (16.7) | 21 (14.4) | 40 (18.7) | |

| N2 | 15 (16.7) | 41 (19.6) | 30 (20.5) | 42 (19.6) | |

| N3 | 38 (42.2) | 59 (28.2) | 48 (32.9) | 73 (34.1) | |

| AJCC stage | 0.587 | ||||

| Stage I | 8 (8.9) | 19 (9.1) | 14 (9.6) | 25 (11.7) | |

| Stage II | 29 (32.2) | 85 (40.7) | 53 (35.3) | 68 (31.8) | |

| Stage III | 53 (58.9) | 105 (50.2) | 79 (54.1) | 121 (56.5) | |

| Differentiation | 0.082 | ||||

| Differentiated | 29 (32.2) | 55 (26.3) | 34 (23.3) | 74 (34.6) | |

| Undifferentiated | 61 (67.8) | 154 (73.7) | 112 (76.7) | 140 (65.4) | |

| LVi | 57 (63.3) | 108 (51.7) | 75 (51.4) | 120 (56.1) | 0.231 |

| PNi | 54 (60.0) | 101 (48.3) | 92 (63.0) | 97 (45.3) | 0.002 |

| Recurrence | 44 (48.9) | 80 (38.3) | 48 (32.9) | 79 (36.9) | 0.648 |

| Local recurrence | 8 (8.9) | 10 (4.6) | 11 (6.9) | 14 (6.2) | 0.637 |

Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to assess the impact of PRM distance on RFS and OS. In the DG group, the mean RFS was 83.8, 90.9, 96.0, and 94.9 mo with a five-year RFS of 35.3%, 41.8%, 47.0%, and 41.0% in the PRM ≤ 1 cm, 1.1-3.0 cm, 3.1-5.0 cm, and > 5 cm subgroups, respectively. In the TG group, the mean RFS was 73.8, 78.5, 88.3, and 83.7 mo with a five-year RFS of 42.2%, 33.0%, 45.9%, and 39.3%, respectively. Neither the DG nor TG group showed statistical differences in either RFS or OS according to the PRM distances (Figures 1 and 2).

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to investigate the impact of the PRM distance and other factors on OS (Tables 4 and 5) and RFS (Tables 6 and 7) using the Cox proportional hazard model. Variable selection for multivariate analysis was done using the backward elimination method with a likelihood ratio test. This revealed that among patients who underwent DG, a higher T stage (T3; P = 0.003, T4; P < 0.001) and N stage (N2, N3; P < 0.001) were associated with worse RFS. Other risk factors included older age (P = 0.012) and reconstruction type; Billroth II (P = 0.016) and RYGJ (P = 0.003) reconstructions resulted in worse RFS than Billroth I reconstruction (Table 6). In the TG group, higher T stage (T4; P = 0.014) and N stage (N2; P = 0.001, N3; P < 0.001) were risk factors associated with RFS. Older age (P = 0.032), linitis plastica (P < 0.001) and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (P = 0.013) were also associated with worse RFS (Table 7). However, neither group showed a significant difference in either RFS or OS according to the distance of the PRM.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | < 0.001 |

| Female sex | 0.89 (0.69-1.15) | 0.367 | ||

| BMI | 0.94 (0.90-0.98) | 0.002 | ||

| Tumor location | ||||

| Upper 1/3 | Ref. | |||

| Mid 1/3 | 3.11 (0.43-22.4) | 0.260 | ||

| Lower 1/3 | 3.54 (0.50-25.2) | 0.208 | ||

| Reconstruction | ||||

| Billroth I | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Billroth II | 1.66 (1.26-2.20) | < 0.001 | 1.40 (1.04-1.87) | 0.025 |

| RYGJ | 1.34 (0.96-1.86) | 0.083 | 1.45 (1.04-2.03) | 0.030 |

| Tumor size | 1.11 (1.06-1.16) | < 0.001 | ||

| Borrmann type IV | 0.96 (0.48-1.94) | 0.914 | ||

| CLN | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.045 | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.034 |

| T stage | ||||

| T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| T3 | 1.36 (1.01-1.83) | 0.044 | 1.08 (0.79-1.48) | 0.612 |

| T4 | 3.02 (2.24-4.06) | < 0.001 | 1.90 (1.38-2.62) | < 0.001 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| N1 | 1.07 (0.73-1.56) | 0.739 | 0.92 (0.63-1.36) | 0.686 |

| N2 | 2.33 (1.67-3.25) | < 0.001 | 2.06 (1.46-2.90) | < 0.001 |

| N3 | 3.74 (2.77-5.05) | < 0.001 | 3.10 (2.25-4.28) | < 0.001 |

| Diffuse type histology | 1.00 (0.79-1.25) | 0.967 | ||

| LVi | 1.82 (1.44-2.29) | < 0.001 | ||

| PNi | 1.32 (1.06-1.66) | 0.015 | ||

| PRM (cm) | ||||

| 0-1.0 | Ref. | |||

| 1.1-3.0 | 0.57 (0.27-1.19) | 0.134 | ||

| 3.1-5.0 | 0.59 (0.29-1.23) | 0.162 | ||

| > 5.0 | 0.61 (0.30-1.25) | 0.175 | ||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | < 0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.03 (0.81-1.30) | 0.834 | ||

| BMI | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) | 0.009 | ||

| Tumor location | ||||

| Upper 1/3 | Ref. | |||

| Mid 1/3 | 0.76 (0.60-0.95) | 0.018 | ||

| Lower 1/3 | 0.94 (0.65-1.35) | 0.723 | ||

| Tumor size | 1.09 (1.07-1.12) | < 0.001 | ||

| Borrmann type IV | 2.21 (1.66-2.94) | < 0.001 | 1.93 (1.43-2.60) | < 0.001 |

| CLN | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.548 | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.035 |

| T stage | ||||

| T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| T3 | 1.67 (1.14-2.45) | 0.008 | 1.21 (0.81-1.81) | 0.352 |

| T4 | 3.24 (2.22-4.72) | < 0.001 | 1.85 (1.22-2.79) | 0.004 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| N1 | 1.11 (0.74-1.68) | 0.617 | 1.03 (0.67-1.57) | 0.900 |

| N2 | 1.73 (1.21-2.46) | 0.003 | 1.48 (1.01-2.18) | 0.045 |

| N3 | 3.87 (2.88-5.19) | < 0.001 | 2.81 (1.98-3.98) | < 0.001 |

| Diffuse type histology | 1.23 (0.96-1.58) | 0.103 | ||

| LVi | 2.09 (1.65-2.64) | < 0.001 | 1.43 (1.10-1.86) | 0.008 |

| PNi | 1.60 (1.27-2.00) | < 0.001 | ||

| PRM (cm) | ||||

| 0-1.0 | Ref. | |||

| 1.1-3.0 | 0.80 (0.57-1.10) | 0.164 | ||

| 3.1-5.0 | 0.65 (0.45-0.93) | 0.019 | ||

| > 5.0 | 0.81 (0.58-1.12) | 0.202 | ||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) | 0.011 | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) | 0.012 |

| Female sex | 0.93 (0.69-1.25) | 0.636 | ||

| BMI | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.068 | ||

| Tumor location | ||||

| Upper 1/3 | Ref. | |||

| Mid 1/3 | 2.32 (0.32-16.77) | 0.403 | ||

| Lower 1/3 | 2.35 (0.33-16.76) | 0.395 | ||

| Reconstruction | ||||

| Billroth I | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Billroth II | 1.90 (1.37-2.64) | < 0.001 | 1.50 (1.08-2.10) | 0.016 |

| RYGJ | 1.87 (1.31-2.67) | 0.001 | 1.72 (1.20-2.47) | 0.003 |

| Tumor size | 1.16 (1.10-1.21) | < 0.001 | ||

| Borrmann type IV | 1.04 (0.46-2.33) | 0.931 | ||

| CLN | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.91 | ||

| T stage | ||||

| T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| T3 | 2.61 (1.72-3.96) | < 0.001 | 1.92 (1.25-2.95) | 0.003 |

| T4 | 6.17 (4.08-9.34) | < 0.001 | 3.42 (2.21-5.31) | < 0.001 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| N1 | 1.23 (0.75-2.03) | 0.415 | 1.03 (0.62-1.70) | 0.92 |

| N2 | 3.42 (2.26-5.19) | < 0.001 | 2.55 (1.67-3.89) | < 0.001 |

| N3 | 5.75 (3.92-8.42) | < 0.001 | 3.88 (2.59-5.80) | < 0.001 |

| Diffuse type histology | 1.19 (0.91-1.57) | 0.206 | 1.05 (0.79-1.39) | 0.758 |

| LVi | 2.29 (1.73-3.02) | < 0.001 | ||

| PNi | 1.63 (1.25-2.12) | < 0.001 | ||

| PRM (cm) | ||||

| 0-1.0 | Ref. | |||

| 1.1-3.0 | 1.03 (0.37-2.86) | 0.949 | ||

| 3.1-5.0 | 0.78 (0.29-2.15) | 0.633 | ||

| > 5.0 | 0.84 (0.31-2.29) | 0.734 | ||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.071 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.032 |

| Female sex | 1.23 (0.95-1.56) | 0.118 | ||

| BMI | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.067 | ||

| Tumor location | ||||

| Upper 1/3 | Ref. | |||

| Mid 1/3 | 0.67 (0.51-0.87) | 0.002 | ||

| Lower 1/3 | 0.86 (0.57-1.30) | 0.859 | ||

| Tumor size | 1.11 (1.08-1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.00-1.07) | 0.075 |

| Borrmann type IV | 2.84 (2.10-3.83) | < 0.001 | 1.91 (1.32-2.76) | 0.001 |

| CLN | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.612 | ||

| T stage | ||||

| T2 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| T3 | 2.20 (1.36-3.54) | 0.001 | 1.31 (0.90-2.16) | 0.289 |

| T4 | 4.18 (2.60-6.72) | < 0.001 | 1.90 (1.14-3.18) | 0.014 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| N1 | 1.43 (0.89-2.31) | 0.139 | 1.27 (0.77-2.07) | 0.348 |

| N2 | 2.35 (1.55-3.56) | < 0.001 | 1.68 (1.06-2.65) | 0.026 |

| N3 | 4.90 (3.43-6.99) | < 0.001 | 2.84 (1.87-4.32) | < 0.001 |

| Diffuse type histology | 1.14 (0.86-1.50) | 0.357 | ||

| LVi | 2.41 (1.84-3.15) | < 0.001 | 1.44 (1.08-1.91) | 0.013 |

| PNi | 1.71 (1.33-2.21) | < 0.001 | ||

| PRM (cm) | ||||

| 0-1.0 | Ref. | |||

| 1.1-3.0 | 0.80 (0.55-1.15) | 0.225 | ||

| 3.1-5.0 | 0.63 (0.42-0.95) | 0.028 | ||

| > 5.0 | 0.74 (0.51-1.07) | 0.104 | ||

It is widely accepted that sufficient resection margins should be achieved for curative resection of gastric cancer. The optimal length for the proximal margin is often suggested to be at least 4-6 cm[8-10]. Over the years, surgical skills and technologies have developed and fields of minimal, less invasive approaches are quickly growing. Guidelines suggest laparoscopic gastrectomy should be performed for early gastric cancer (EGC) in the distal third of the stomach[9] and laparoscopic TG was recently demonstrated to be safe and feasible for EGC. Moreover, there are ongoing trials and studies for laparoscopic approaches in advanced cancer, particularly in eastern countries. However, surgeons still abide by conventional rules and try to achieve the recommended margin length, even in difficult conditions.

Several studies are rooted in this discrepancy in the appropriate PRM distance. In 2006, Ha et al[19] reported that PRM had no significant influence on the prognosis of EGC patients; however, a PRM length of > 3 cm improved the survival rates in AGC patients. Squires et al[15] reported their findings from a 2015 study based on 465 patients who underwent curative-intent gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer. Their results indicated that a proximal margin distance > 3 cm is associated with better OS and RFS in stage I disease, whereas the proximal margin distance did not significantly improve prognosis in either stage II or III disease. The authors concluded that a proximal margin of > 3 cm is optimal for distal gastric cancer. Wang et al[12] reported that a proximal margin of 2.1-4.0 cm and 4.1-6.0 cm should be obtained for patients with solitary- and infiltrative-type tumors, respectively, for better prognoses. In 2017, based on 974 patients with gastric and esophago-gastric junction cancer, Bissolati et al[17] reported that a resection margin, either proximal or distal, that is < 2 cm for T1 cancer and < 3 cm for T2-4 cancer is associated with resection margin involvement, which was demonstrated in previous literature to have a negative prognostic impact[20-24]. However, Kim et al[13] reported in 2014 that the length of the proximal margin did not affect the OS or local recurrence and several subsequent studies have arrived at similar conclusions[11,14,18].

The conclusions regarding the safe length of PRM, particularly for AGC patients, are not consistent even among recent papers. Thus, we designed a large-scale study to determine the optimal length of the PRM for patients with AGC. Cross-tabulation analysis with our data showed that the incidence of recurrence or local recurrence according to the distance of the PRM did not differ (P > 0.05) in patients who underwent DG or TG for AGC. We performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to assess the effect of the PRM distance on RFS and our results showed no statistical difference in RFS between the PRM subgroups. Multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model revealed consistent results. Although previous reports do not agree on the safety of short resection margins, particularly in AGC, our results demonstrate that the distance of the PRM did not affect the prognosis of AGC patients who underwent curative gastrectomy.

Our multivariate analysis of influential factors in RFS and OS for patients who underwent DG showed significant differences between different reconstruction methods; this is inconsistent with previous literature. Billroth I was the most preferred reconstruction method after gastrectomy for gastric cancer patients at our institution. When a tumor involved pylorus or the stomach stump was too short for gastroduodenostomy, Billroth II or RYGJ was applied. Therefore, there is a chance that cases with B-II and RYGJ anastomosis were associated with larger and more progressed tumors. Another possible reason is that because Billroth I is the most preferred method in our institution, surgeons were more comfortable with the procedure, resulting in better outcomes. Although there is no consensus, a number of studies reveal more gastric stump cancer in patients who underwent Billroth II reconstruction rather than Billroth I after gastrectomy either due to carcinoma or benign lesions[25-27]. There is also an RCT from Japan that shows more hematogenous recurrence in B-II compared to B-I[28]. This is an important result that warrants further investigation with a careful design, taking many factors such as recurrence patterns, recurred time after surgery, histology of the initial tumor, and many other factors into consideration.

There is a limitation in the retrospective design of this study. Another limitation is that the length of the resection margin used in the study may not accurately portray the gross distance we observe intraoperatively. We used the PRM as described on the pathologic report, which was measured under formalin fixation. We chose to use the pathologic report because measurements from the operation room are expected to be less consistent depending on the measured time after resection or in cases with indistinctive tumor margins such as linitis plastica. Additionally, for TG, we used circular staplers that produce doughnut specimens that are not added to the length of PRM, so the actual PRM may be few millimeters longer than measured.

In conclusion, the distance of PRM is not a prognostic factor for AGC patients; it does not affect the incidence of recurrence or local recurrence. A greater PRM distance was not associated with better survival outcomes and a distance of < 1 cm did not correlate with worse OS or RFS.

The conventional guidelines suggest the surgeons to obtain an extensive resection margin during surgery for gastric cancer. Several recent studies have raised questions regarding the need for such extensive resection and necessity of total gastrectomy for tumors located on middle-third of stomach, while the consensus has not been reached. There are some studies those demonstrate the unnecessity of longer proximal resection margin (PRM) distance in early gastric cancer. However, there are very few regarding the PRM distance for advanced gastric cancer (AGC).

We would like to discover the optimal PRM distance for patients who undergo gastrectomy for AGC.

The objective of this study was to investigate the influence of the PRM distance on the oncologic outcomes of patients who underwent gastrectomy for AGC, thus to prove the safety of the PRM distance shorter than the conventional literatures suggest.

We retrospectively collected data from 1518 patients who underwent total gastrectomy (TG) or distal gastrectomy (DG) for AGC between June 2004 and December 2007. The distances of the PRM and DRM were defined as the shortest distance from the most proximal or distal end to each resection line, measured on formalin-fixed surgical specimens by pathologists. The demographics and clinicopathologic outcomes were compared according to the different PRM categories and an analysis on the influence of PRM on recurrence-free survival and overall survival was performed.

The DG and TG groups showed no statistical difference in RFS or OS according to the distance of PRM. Multivariate analysis also revealed that in both groups, there was no significant difference in RFS or OS according to the PRM distance.

The distance of PRM did not affect the incidence of recurrence or local recurrence. A greater PRM distance was not associated with better survival outcomes and a distance as short as < 1 cm did not correlate with worse OS or RFS. Therefore, the PRM distance shorter than conventional literatures suggest may be accepted.

Further research would be essential to set a guideline for the optimal PRM distance for AGC. A long-term prospective study with detailed data on PRM including measurements done during operation by the surgeons and after fixation by the pathologists should give better answers.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alimoğlu O, Ilhan E, Tian YT, Xiao JW S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Fock KM. Review article: the epidemiology and prevention of gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:250-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferro A, Peleteiro B, Malvezzi M, Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Levi F, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Lunet N. Worldwide trends in gastric cancer mortality (1980-2011), with predictions to 2015, and incidence by subtype. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1330-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 502] [Article Influence: 45.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Levi F, Praud D, Ferlay J, Negri E, Malvezzi M, La Vecchia C. Recent patterns in gastric cancer: a global overview. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:666-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 484] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Coccolini F, Montori G, Ceresoli M, Cima S, Valli MC, Nita GE, Heyer A, Catena F, Ansaloni L. Advanced gastric cancer: What we know and what we still have to learn. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1139-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Davies J, Johnston D, Sue-Ling H, Young S, May J, Griffith J, Miller G, Martin I. Total or subtotal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma? A study of quality of life. World J Surg. 1998;22:1048-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Svedlund J, Sullivan M, Liedman B, Lundell L, Sjödin I. Quality of life after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma: controlled study of reconstructive procedures. World J Surg. 1997;21:422-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee K, Won Kim K, Lee JB, Shin Y, Kyoo Jang J, Yook JH, Kim B, Lee IS. Effect of the Remnant Stomach Volume on the Nutritional and Body Composition in Stage 1 Gastric Cancer Patients. Surg Metab Nutr. 2018;9:41-50. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bozzetti F, Bonfanti G, Bufalino R, Menotti V, Persano S, Andreola S, Doci R, Gennari L. Adequacy of margins of resection in gastrectomy for cancer. Ann Surg. 1982;196:685-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1915] [Article Influence: 239.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Ajani JA, Barthel JS, Bekaii-Saab T, Bentrem DJ, D'Amico TA, Das P, Denlinger C, Fuchs CS, Gerdes H, Hayman JA, Hazard L, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Keswani RN, Kleinberg LR, Korn M, Meredith K, Mulcahy MF, Orringer MB, Osarogiagbon RU, Posey JA, Sasson AR, Scott WJ, Shibata S, Strong VE, Washington MK, Willett C, Wood DE, Wright CD, Yang G; NCCN Gastric Cancer Panel. Gastric cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:378-409. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lee CM, Jee YS, Lee JH, Son SY, Ahn SH, Park DJ, Kim HH. Length of negative resection margin does not affect local recurrence and survival in the patients with gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10518-10524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang J, Liu J, Zhang G, Kong D. Individualized proximal margin correlates with outcomes in gastric cancers with radical gastrectomy. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317711032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim MG, Lee JH, Ha TK, Kwon SJ. The distance of proximal resection margin dose not significantly influence on the prognosis of gastric cancer patients after curative resection. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;87:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ohe H, Lee WY, Hong SW, Chang YG, Lee B. Prognostic value of the distance of proximal resection margin in patients who have undergone curative gastric cancer surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Squires MH, Kooby DA, Poultsides GA, Pawlik TM, Weber SM, Schmidt CR, Votanopoulos KI, Fields RC, Ejaz A, Acher AW, Worhunsky DJ, Saunders N, Levine EA, Jin LX, Cho CS, Bloomston M, Winslow ER, Russell MC, Cardona K, Staley CA, Maithel SK. Is it time to abandon the 5-cm margin rule during resection of distal gastric adenocarcinoma? A multi-institution study of the U.S. Gastric Cancer Collaborative. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1243-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim JH, Park SS, Kim J, Boo YJ, Kim SJ, Mok YJ, Kim CS. Surgical outcomes for gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. World J Surg. 2006;30:1870-1876; discussion 1877-1878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bissolati M, Desio M, Rosa F, Rausei S, Marrelli D, Baiocchi GL, De Manzoni G, Chiari D, Guarneri G, Pacelli F, De Franco L, Molfino S, Cipollari C, Orsenigo E. Risk factor analysis for involvement of resection margins in gastric and esophagogastric junction cancer: an Italian multicenter study. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:70-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jang YJ, Park MS, Kim JH, Park SS, Park SH, Kim SJ, Kim CS, Mok YJ. Advanced gastric cancer in the middle one-third of the stomach: Should surgeons perform total gastrectomy? J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:451-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ha TK, Kwon SJ. Clinical Importance of the Resection Margin Distance in Gastric Cancer Patients. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2006;6:277. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim SH, Karpeh MS, Klimstra DS, Leung D, Brennan MF. Effect of microscopic resection line disease on gastric cancer survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:24-33. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Cho BC, Jeung HC, Choi HJ, Rha SY, Hyung WJ, Cheong JH, Noh SH, Chung HC. Prognostic impact of resection margin involvement after extended (D2/D3) gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a 15-year experience at a single institute. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:461-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sun Z, Li DM, Wang ZN, Huang BJ, Xu Y, Li K, Xu HM. Prognostic significance of microscopic positive margins for gastric cancer patients with potentially curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3028-3037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nagata T, Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Inoue K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Sakakura C, Otsuji E. Prognostic impact of microscopic positive margin in gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:592-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sano T, Mudan SS. No advantage of reoperation for positive resection margins in node positive gastric cancer patients? Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29:283-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Păduraru DN, Nica A, Ion D, Handaric M, Andronic O. Considerations on risk factors correlated to the occurrence of gastric stump cancer. J Med Life. 2016;9:130-136. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kwon TG, Kim KH, Seo SH, Jeong IS, Park YH, An MS, Ha TK, Bae KB, Choi CS, Oh SH. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of remnant gastric cancer. Korean J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:83-91. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tanigawa N, Nomura E, Lee SW, Kaminishi M, Sugiyama M, Aikou T, Kitajima M; Society for the Study of Postoperative Morbidity after Gastrectomy. Current state of gastric stump carcinoma in Japan: based on the results of a nationwide survey. World J Surg. 2010;34:1540-1547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Morita M, Nabeshima K, Nakamura K, Kondoh Y, Ogoshi K. Which is better long-term survival of gastric cancer patients with Billroth I or Billroth II reconstruction after distal gastrectomy? -Impact on 20-year survival rate. Ann Cancer Res Ther. 2013;21:20-25. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |