Published online Mar 21, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i11.1221

Peer-review started: December 5, 2019

First decision: January 16, 2020

Revised: February 10, 2020

Accepted: March 5, 2020

Article in press: March 5, 2020

Published online: March 21, 2020

Processing time: 106 Days and 9.4 Hours

System based practice (SBP) milestones require trainees to effectively navigate the larger health care system for optimal patient care. In gastroenterology training programs, the assessment of SBP is difficult due to high volume, high acuity inpatient care, as well as inconsistent direct supervision. Nevertheless, structured assessment is required for training programs. We hypothesized that objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) would be an effective tool for assessment of SBP.

To develop a novel method for SBP milestone assessment of gastroenterology fellows using the OSCE.

For this observational study, we created 4 OSCE stations: Counseling an impaired colleague, handoff after overnight call, a feeding tube placement discussion, and giving feedback to a medical student on a progress note. Twenty-six first year fellows from 7 programs participated. All fellows encountered identical case presentations. Checklists were completed by trained standardized patients who interacted with each fellow participant. A report with individual and composite scores was generated and forwarded to program directors to utilize in formative assessment. Fellows also received immediate feedback from a faculty observer and completed a post-session program evaluation survey.

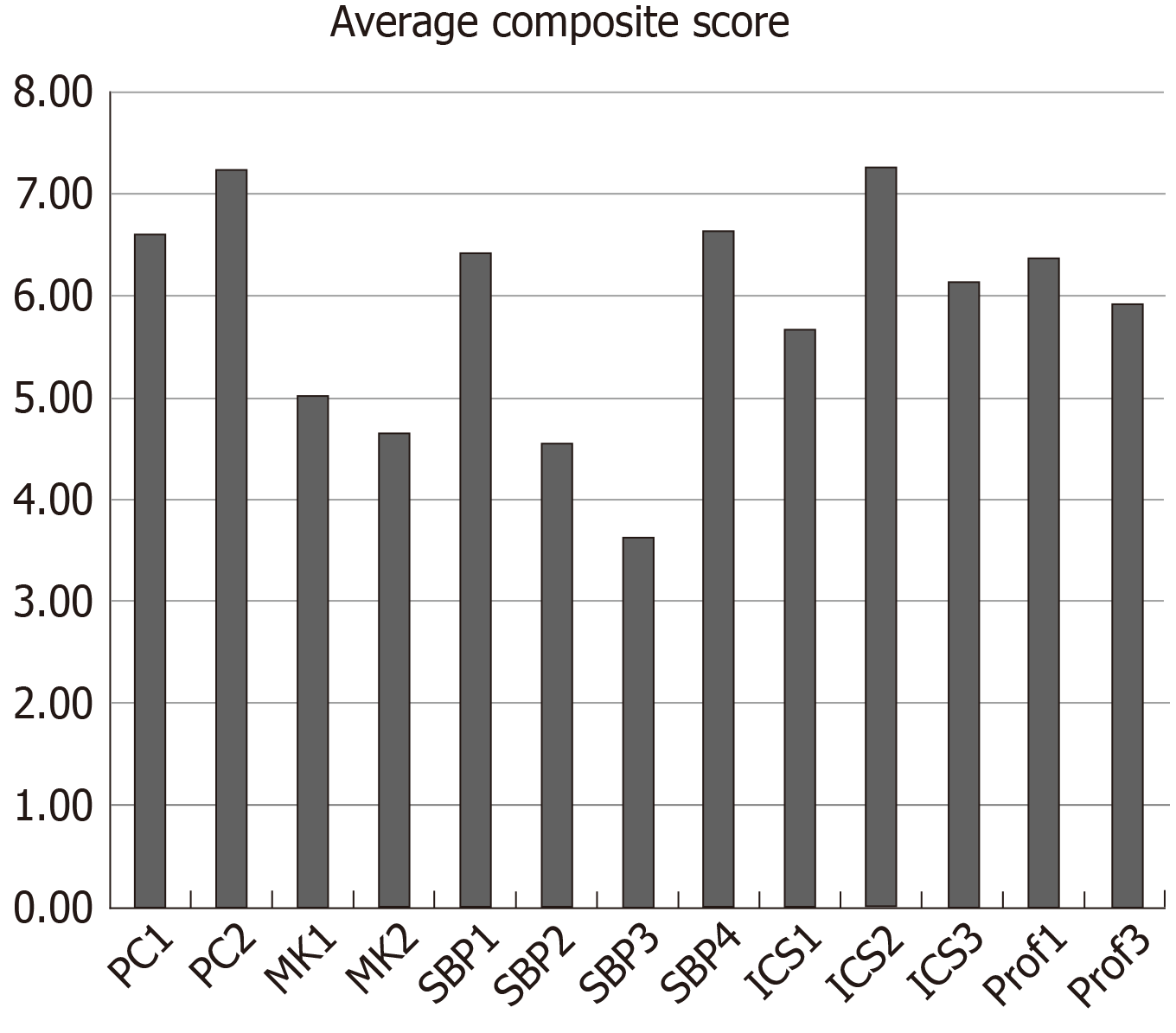

Survey response rate was 100%. The average composite score across SBP milestones for all cases were 6.22 (SBP1), 4.34 (SBP2), 3.35 (SBP3), and 6.42 (SBP4) out of 9. The lowest composite score was in SBP 3, which asks fellows to advocate for cost effective care. This highest score was in patient care 2, which asks fellows to develop comprehensive management plans. Discrepancies were identified between the fellows’ perceived performance in their self-assessments and Standardized Patient checklist evaluations for each case. Eighty-seven percent of fellows agreed that OSCEs are an important component of their clinical training, and 83% stated that the cases were similar to actual clinical encounters. All participating fellows stated that the immediate feedback was “very useful.” One hundred percent of the fellows stated they would incorporate OSCE learning into their clinical practice.

OSCEs may be used for standardized evaluation of SBP milestones. Trainees scored lower on SBP milestones than other more concrete milestones. Training programs should consider OSCEs for assessment of SBP.

Core tip: In United States medical training, system based practice (SBP) milestones are often considered the most difficult to both teach and assess. While the objective standardized clinical examination is a well validated method for assessment in medical education, its use for assessment of specific SBP milestones has not been well studied. In this observational study, we created and implemented objective standardized clinical examinations geared towards assessment of SBP milestones in gastroenterology fellows in scenarios engineered to provide opportunity for medical error. We show that this method provides objective assessment of trainees for program use and may help trainees feel more prepared for real world situations.

- Citation: Papademetriou M, Perrault G, Pitman M, Gillespie C, Zabar S, Weinshel E, Williams R. Subtle skills: Using objective structured clinical examinations to assess gastroenterology fellow performance in system based practice milestones. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(11): 1221-1230

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i11/1221.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i11.1221

Medical education assessment in the United States is currently based on six competencies as defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 1999: Patient care (PC), medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills(ICS), and system based practice (SBP)[1].

The SBP competencies require trainees to effectively recognize and navigate the larger healthcare system for optimal PC. While these are important skills to build, they are difficult to define and assess in a standardized way in daily clinical encounters. For gastroenterology (GI) fellowships in the United States, the high acuity of inpatient consultations with little time for complete direct observation necessitates focus on tools to evaluate all milestones in addition to SBP[2-5]. Simulation based medical education such as the objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) are now a standard methodology for assessing clinical skill and knowledge in medical education[1]. OSCEs are the foundation of Step 2 CS of the United States Medical Licensing Examination. They have the advantage of assessing large groups of learners across a range of skills by recreating situations where there is limited opportunity for supervision and feedback with high validity and reliability[6]. While many studies have corroborated the effectiveness of OSCEs for learner assessment, there are few papers that have evaluated this setting as an effective teaching tool as well[2,7].

Furthermore, SBP milestones are particularly difficult to evaluate objectively and reproducibly in everyday clinical encounters and may be even more difficult to teach in the course of typical clinical encounters[8].

The purpose of our program was to assess first year GI fellows’ skills in SBP milestones utilizing OSCEs that created opportunity for medical errors. We hypothesized that the OSCE would be an effective tool for assessment of SBP.

This is the first paper to our knowledge to focus on these milestones in GI trainees.

Four cases were developed to assess several ACGME milestones (PC, medical knowledge, ICS, SBP, professionalism). Medical education and GI content experts reviewed all 4 cases prior to implementation.

Impaired colleague: The fellows were asked to give sign out to a co-fellow demonstrating emotional and substance-related impairment. Participants were not forewarned of the impaired colleague, but were expected to screen for depression, life stressors, and substance use based on verbal and behavioral cues. This case was adapted from prior use for assessment with faculty and internal medicine residents.

Overnight handoff: The fellows were asked to give handoff to a senior fellow on an acutely ill patient and were in part evaluated on use of best practices from Illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness, synthesis (I-PASS), a validated handoff tool mnemonic that stands for Illness Severity, Patient Summary, Action List, Situation Awareness, and Synthesis by the Receiver[9]. Fellows were given I-PASS resources in the days prior to the OSCE but were not required to review them. We adapted this case's checklist from a previously utilized scenario[10].

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement: The fellows were asked to discuss percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement with the health care proxy of a patient in a persistent vegetative state. The proxy was aware that the patient had expressed wishes not to have a feeding tube placed prior to becoming ill. This case was newly developed for this OSCE.

Note feedback: The fellows were asked to meet with a medical student and give feedback on a consult note which contained multiple documentation errors. This case was redesigned from a previously validated case for internal medicine residents.

Actors with prior OSCE experience performed the roles of the impaired colleague and the patient’s health care proxy in the PEG case. A senior GI fellow and a medical student performed the necessary roles in the overnight handoff case and in the note feedback case, respectively. Collectively these individuals were referred to as standardized persons (SPs). The SPs underwent a 2-hour training session with scripts and role-play to ensure standardization of case portrayals and assessment. The program was held in 3 sessions with different fellows participating in one of each of the three sessions over a 2-year period. The OSCEs were run during the late fall or winter period both years in order to ensure all fellows had spent similar time in fellowship training at time of participation. First year GI fellows were recruited via email to their program directors, and participation was voluntary. All participating fellows encountered identical case presentations with the same SPs and faculty observers and had 12 min to perform each scenario, followed by a 3-minute feedback session. The exception was the senior fellow SP, where two different fellows played this role based on availability. The SPs completed OSCE checklists scoring each fellow immediately after each encounter.

We utilized validated checklists completed by the faculty observers and SPs and a post-session program evaluation tool completed by participants[11]. The checklists also included case specific questions that highlighted milestones of SBP and were reviewed by content experts prior to implementation[3,4,12,13].

The checklist items were correlated with specific ACGME milestones and were rated on a 3-point scale of “not done” (the fellow did not attempt the task), “partly done” (the fellow attempted the task, but did not perform it correctly), and “well done” (the fellow performed the task correctly). The score for each milestone was converted from this three-point scale to a composite milestone score across all the cases. For example, a participant’s score for that milestone (ex. PC 1) across all the cases was divided by the total possible score which yielded a number less than 1. This number was then multiplied by 9 to get the composite score for each milestone. This allowed us to compare score between different milestones.

A report with individual and composite scores was generated and forwarded to program directors to utilize in formative assessment (Supplemental Figure 1). Following each session, fellows had a debriefing session to review the teaching points, discuss the experience and provide open-ended feedback. They also completed an exit survey assessing pre- and post-OSCE perceptions and beliefs about competencies, educational value of the experience, and case difficulty. We collected and managed the data using Research Electronic Data Capture, a secure, web-based application[14].

This program was considered an educational performance improvement project by the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and was not considered for IRB approval.

Twenty-six first year fellows from seven GI training programs in New York City participated. Survey response rate was 100%, however, 2 surveys contained missing data and responses for those questions were not included in the calculation.

The average composite milestone scores for all 26 learners across all four OSCE cases are reported in Figure 1. A wide variation in performance was noted across the evaluated milestone metrics. The lowest composite score was in SBP 3 (identifies forces that impact the cost of health care, and advocates for, and practices cost-effective care), where the mean score was 3.64 out of 9 points. In comparison, the highest composite score was seen in PC2 (develops and achieves comprehensive management plan for each patient), with a mean score of 7.25.

We evaluated how participants felt they performed in each case (Tables 1 and 2). This can be contrasted with the scores given by the SPs. SPs documented whether particular course objectives were met, which were individualized for each case. Fellows were provided each case objective during the debriefing. In the PEG case, 88% of the fellows felt they were well prepared for the case and 66% felt they did well achieving the case objectives. Conversely, only 11% of fellows were rated by the SP to have engaged in shared decision making and no fellows were noted to have assessed the SP’s basic understanding of risks, two points which were identified as case objectives. No fellow fully evaluated for depression, suicidal ideation or alcohol use in the Impaired Colleague case. Only 33% screened for depression and collaborated on identifying next steps. Participants indicated they felt more prepared for these scenarios after the OSCE than before. This difference was most striking for the PEG case and Impaired Colleague case.

| How would you rate your overall performance in this case? | Could have been better | Fine | Pretty good |

| Impaired colleague | 9 (34.6) | 9 (34.6) | 8 (30.8) |

| Hand off with I-PASS | 2 (7.7) | 15 (57.7) | 9 (34.6) |

| PEG tube discussion | 9 (34.6) | 9 (34.6) | 8 (30.8) |

| Note-writing and feedback | 2 (7.7) | 13 (50) | 11 (42.3) |

Participants were asked about their preparedness and performance on the cases in an exit survey. These results are summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. The fellows rated their performance highly in the Handoff and note feedback cases, with 92.3% of respondents stating their performance was either “fine” or “pretty good.” Self-assessment scores were lower for the PEG discussion and Impaired Colleague case, with 34.6% of respondents stating their performance “could have been better,” in both cases (Tables 1 and 2). The participants’ overall views of the OSCE are reported in Table 4. In general, the participants responded favorably: Eighty-seven percent agreed that OSCEs are an important component of their clinical training, and 83% stated that the cases were similar to actual clinical encounters. All of the respondents stated that the immediate feedback was “very useful,” and 100% of respondents stated they would incorporate OSCE learning into their clinical practice. For each case, a majority of respondents stated they would feel more comfortable in a similar situation after the OSCE than they did before.

| Items | Strongly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Somewhat agree | Strongly agree |

| Before today’s OSCE, I felt comfortable discussing the utility of PEG placement in a patient with neurologic compromise | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 16 (67) | 5 (21) |

| After today’s OSCE, I feel more comfortable discussing the utility of PEG placement in a patient with neurologic compromise | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (42) | 14 (58) |

| Before today’s OSCE, I felt comfortable during hand-off discussions with my co-fellows | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 10 (42) | 13 (54) |

| After today’s OSCE, I feel more comfortable during hand-off discussions with my co-fellows | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 8 (33) | 15 (63) |

| Before today’s OSCE, I felt comfortable that I would be able to recognize signs of substance abuse and depression in a colleague and referring them to the appropriate resources | 2 (8) | 5 (21) | 12 (50) | 5 (21) |

| After today’s OSCE, I feel comfortable that I would be able to recognize signs of substance abuse and depression in a colleague and referring them to the appropriate resources | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (42) | 14 (58) |

| Before today’s OSCE, I felt very comfortable giving constructive criticism and feedback to my learners | 0 (0) | 2 (9) | 13 (57) | 8 (35) |

| After today’s OSCE, I feel more comfortable giving constructive criticism and feedback to my learners | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 6 (26) | 16 (70) |

| Items | Strongly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Somewhat agree | Strongly agree |

| OSCEs are an important part of my clinical training | 0 (0) | 3 (13) | 11 (48) | 9 (39) |

| My performance on this OSCE accurately reflects my performance in clinical practice | 1 (4) | 5 (21) | 13 (54) | 5 (21) |

| These OSCE cases are similar to actual encounters | 0 (0) | 4 (17) | 13 (54) | 7 (29) |

| The immediate feedback that I received is very useful | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (17) | 20 (83) |

| I generally perform better on the OSCE than in clinical practice | 8 (33) | 14 (58) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) |

| I generally do better in clinical practice than I do in an OSCE | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 12 (50) | 9 (38) |

| OSCEs makes me feel anxious | 3 (13) | 4 (17) | 12 (50) | 5 (21) |

| OSCEs are an effective means of demonstrating my interpersonal skills | 0 (0) | 3 (13) | 16 (67) | 5 (21) |

| OSCEs are an effective means of demonstrating my ability to demonstrate a shared decision-making approach to patient care | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 15 (63) | 7 (29) |

| My clinical training fully prepared me for this OSCE | 1 (4) | 3 (13) | 14 (58) | 6 (25) |

| After I receive feedback on the OSCE, I will develop a plan to improve my clinical skills | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (50) | 12 (50) |

| I will incorporate what I have learned from this OSCE into my clinical practice | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (38) | 15 (63) |

| If you have participated in this OSCE before: Did your prior OSCE experience affect your participation today? | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (31) | 9 (69) |

Our main objective was to assess SBP milestones using novel OSCE cases. We were also interested to see if participants felt the experience was helpful as a teaching tool, although we could not assess teaching utility in this observational study.

We highlighted the following SBP milestones in our handoff and feedback cases: SBP1 “works effectively within an inter-professional team”; SBP3 “Recognized system error and advocated for system improvement”; and SBP4, “Transitions patients effectively within and across health delivery systems.”

A recent report calculated medical errors as the third leading cause of death within the United States[15]. Handoffs are vulnerable to communication failures that can compromise quality and safety[16-18]. A 2007 analysis of malpractice claims involving trainees found that 70% of the errors involved the lack of supervision and hand-off errors. These types of errors were disproportionately more common amongst trainees vs faculty[19]. Studies have demonstrated that standardizing handoffs leads to better communication between physicians and, ultimately, to safer PC[20,21]. Specifically, the mnemonic I-PASS has been shown prospectively to reduce medical errors[9]. In this OSCE, participants were given learning materials explaining the I-PASS format and were provided immediate feedback about critical communication. More fellows agreed with feeling prepared to give adequate hand off after the OSCE than did beforehand.

Graduate medical trainees also have important responsibilities to supervise and teach junior learners, yet rarely receive formal instruction on how to deliver feedback effectively. A survey of 50 graduate medical education programs found that trainees had a lower perception than staff in the “communication and feedback about error” domain, indicating trainees do not feel they obtain regular feedback when an error occurs[22]. After our feedback case, the number of fellows who strongly agreed they felt comfortable giving constructive criticism doubled from 35% to 70%.

We found discrepancies between how fellows felt they met case objectives vs how they were scored, most apparent in the PEG and the impaired colleague scenarios. These cases highlight complex situations, which we believe early trainees have not often experienced. Our PEG discussion case allowed participants to demonstrate SBP3: Competency advocating cost effective care. The case focused on sensitive issues of end of life counseling and discussing risks and benefits of a procedure - skills which fellows were least likely to demonstrate when compared to other PC skills[13]. Similarly, in this OSCE, fellows scored the lowest on the PEG case and the lowest average composite score in SBP3.

The case involving sign out to an impaired colleague is especially relevant with the current focus on physician depression, burnout and suicide. Fellows had to recognize that having an impaired colleague care for patients would directly compromise patient safety. While this situation is rare, the risks are high and the issues are complex. Singh et al[19] also found that 72% of medical errors involved an error in judgment and 58% a lack of competence, both of which would be present in an impaired physician. Twenty four percent of fellows felt they were not prepared for this case, the most of any of the four cases. The number of fellows who strongly agreed they could recognize signs of substance abuse and depression in a colleague more than doubled after the OSCE.

SBP milestones are difficult to assess objectively during GI training programs, as fellows may not be directly observed in situations where these competencies are required. Importantly, fellows’ self-reported comfort levels increased after every OSCE case. Fellows reflected positively on the experience in the post participation survey. They universally felt that the immediate feedback was useful and would improve their clinical skills. All participants stated they would recommend this OSCE as an assessment and training tool. At the conclusion of our study, each fellow was provided a comprehensive report card documenting their performance, which could be utilized by the training program (Supplemental Figure 1). SBP milestone was shown in Supplemental Table 1.

The limitations of our OSCE study are inherent to studies involving subjective assessment, although our instructors and standardized patients were trained prior to the OSCE on scoring and the same individuals scored all 26 participants. Secondly, our study was small, as each OSCE was resource intensive. Lastly, as this was not a longitudinal study, we could not assess whether participation in and feedback from the OSCE improved performance in SBP. An interesting future direction could include the repeat assessment of the participating fellows at the end of their training to assess change in performance over time and to compare them to fellows who did not participate in the OSCE in their first year. In conclusion, OSCEs can be utilized to assess SBP milestones in high risk scenarios linked to medical errors.

Medical education assessment in the United States is currently based on six competencies as defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Gastroenterology (GI) training programs must assess trainees according in all six competencies as part of formative feedback. The system based practice (SBP) competencies require trainees to effectively recognize and navigate the larger healthcare system for optimal patient care. These milestones may be considered more subtle skills to master than other concrete milestones such as patient care and medical knowledge.

SBP milestones are difficult to observe and assess in daily clinical encounters between patients and trainees. Therefore, alterative objective activities may be necessary to adequately assess achievement in SBP. Simulation based medical education such as the Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) are now a standard methodology for assessing clinical skill and knowledge in medical education. OSCEs have not been previously used to assess SBP milestones specifically.

The main objective of this research study was to create and then evaluate OSCEs as an effective assessment tool for the evaluation of SBP milestones. We aimed to see if new clinical scenarios commonly encountered by GI trainees would be useful in this assessment. We also sought to evaluate how trainees felt about the experience.

We developed four cases to help assess the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones with a focus on SBP. Trainees went through these four simulations with standardized patients and were evaluated by faculty experts using standardized checklists. Their performance from the checklists were aggregated and used to produce a scorecard which was sent to program directors at the conclusion of the OSCE. The trainees were then given direct feedback from the standardized patients and the faculty observer. Finally, the trainees were asked to complete a survey on the experience.

We ran three OSCE sessions involving 26 GI trainees. Scorecards indicated that, on average, trainees scored lower on SBP milestones than on other milestones categories. We identified and reported discrepancies between how well trainees believed they achieved objectives, and how they were rated by the standardized patients and faculty observers. Overall, trainees reflected positively on the experience in the post participation survey. They universally felt that the immediate feedback was useful and would improve their clinical skills. All participants stated they would recommend this OSCE as an assessment and training tool.

In this study we demonstrated that OSCEs may be utilized to assess SBP milestones in an objective manner. Since SBP milestones may be difficult to assess in day-to-day activities in the hospital or clinic setting, training programs may want to utilize this type of standardized case-based simulation for assessment. Likewise, trainees reflected positively on the experience and felt they would incorporate feedback into their daily practice.

Future studies are needed to assess if OSCEs may be useful teaching tools for SBP milestones. This would require repeat assessment with the same OSCE at the GI fellows’ completion of training and comparison of this group to a group who did not participate in the initial OSCE in their first year.

Manuscript source: Invited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Caboclo JF S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | The Accrediting Council of Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Internal Medicine Subspecialties. 2015 Jul [cited 20 January 2020]. Available from: URL: https://acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineSubspecialtyMilestones.pdf?ver=2015-11-06-120527-673. |

| 2. | Chander B, Kule R, Baiocco P, Chokhavatia S, Kotler D, Poles M, Zabar S, Gillespie C, Ark T, Weinshel E. Teaching the competencies: using objective structured clinical encounters for gastroenterology fellows. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:509-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Holmboe ES, Hawkins RE. Methods for evaluating the clinical competence of residents in internal medicine: a review. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jain SS, DeLisa JA, Nadler S, Kirshblum S, Banerjee SN, Eyles M, Johnston M, Smith AC. One program's experience of OSCE vs. written board certification results: a pilot study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79:462-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sedlack RE. The Mayo Colonoscopy Skills Assessment Tool: validation of a unique instrument to assess colonoscopy skills in trainees. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1125-1133, 1133.e1-1133.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Papadakis MA. The Step 2 clinical-skills examination. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1703-1705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alevi D, Baiocco PJ, Chokhavatia S, Kotler DP, Poles M, Zabar S, Gillespie C, Ark T, Weinshel E. Teaching the competencies: using observed structured clinical examinations for faculty development. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:973-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Johnson JK, Miller SH, Horowitz SD. Systems-Based Practice: Improving the Safety and Quality of Patient Care by Recognizing and Improving the Systems in Which We Work. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2008. |

| 9. | Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, West DC, Rosenbluth G, Allen AD, Noble EL, Tse LL, Dalal AK, Keohane CA, Lipsitz SR, Rothschild JM, Wien MF, Yoon CS, Zigmont KR, Wilson KM, O'Toole JK, Solan LG, Aylor M, Bismilla Z, Coffey M, Mahant S, Blankenburg RL, Destino LA, Everhart JL, Patel SJ, Bale JF, Spackman JB, Stevenson AT, Calaman S, Cole FS, Balmer DF, Hepps JH, Lopreiato JO, Yu CE, Sectish TC, Landrigan CP; I-PASS Study Group. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1803-1812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 539] [Cited by in RCA: 607] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Williams R, Miler R, Shah B, Chokhavatia S, Poles M, Zabar S, Gillespie C, Weinshel E. Observing handoffs and telephone management in GI fellowship training. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1410-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zabar S. Objective structured clinical examinations: 10 steps to planning and implementing OSCEs and other standardized patient exercises. 1st ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 2013. |

| 12. | Farnan JM, Paro JA, Rodriguez RM, Reddy ST, Horwitz LI, Johnson JK, Arora VM. Hand-off education and evaluation: piloting the observed simulated hand-off experience (OSHE). J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shah B, Miler R, Poles M, Zabar S, Gillespie C, Weinshel E, Chokhavatia S. Informed consent in the older adult: OSCEs for assessing fellows' ACGME and geriatric gastroenterology competencies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1575-1579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38562] [Cited by in RCA: 36531] [Article Influence: 2283.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1419] [Cited by in RCA: 1414] [Article Influence: 157.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Arora V, Johnson J, Lovinger D, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer DO. Communication failures in patient sign-out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. Consequences of inadequate sign-out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1755-1760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79:186-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 656] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Singh H, Thomas EJ, Petersen LA, Studdert DM. Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2030-2036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sinha M, Shriki J, Salness R, Blackburn PA. Need for standardized sign-out in the emergency department: a survey of emergency medicine residency and pediatric emergency medicine fellowship program directors. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:192-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, Jaeger J, Rosenfeld JC, Patow C, Padmore JS, Karpovich KP. Residents' and attending physicians' handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775-1787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bump GM, Coots N, Liberi CA, Minnier TE, Phrampus PE, Gosman G, Metro DG, McCausland JB, Buchert A. Comparing Trainee and Staff Perceptions of Patient Safety Culture. Acad Med. 2017;92:116-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |