Published online Mar 14, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i10.1080

Peer-review started: December 4, 2019

First decision: December 30, 2019

Revised: January 10, 2020

Accepted: February 15, 2020

Article in press: February 15, 2020

Published online: March 14, 2020

Processing time: 101 Days and 13.8 Hours

Endoscopic balloon dilatation (EBD) has become the first line of therapy for benign esophageal strictures (ESs); however, there are few publications about the predictive factors for the outcomes of this treatment.

To assess the predictive factors for the outcomes of EBD treatment for strictures after esophageal atresia (EA) repair.

Children with anastomotic ES after thoracoscopic esophageal atresia repair treated by EBD from January 2012 to December 2016 were included. All procedures were performed under tracheal intubation and intravenous anesthesia using a three-grade controlled radial expansion balloon with gastroscopy. Outcomes were recorded and predictors of the outcomes were analyzed.

A total of 64 patients were included in this analysis. The rates of response, complications, and recurrence were 96.77%, 8.06%, and 2.33%, respectively. The number of dilatation sessions and complications were significantly higher in patients with a smaller stricture diameter (P = 0.013 and 0.023, respectively) and with more than one stricture (P = 0.014 and 0.004, respectively). The length of the stricture was significantly associated with complications of EBD (P = 0.001). A longer interval between surgery and the first dilatation was related to more sessions and a poorer response (P = 0.017 and 0.024, respectively).

The diameter, length, and number of strictures are the most important predictive factors for the clinical outcomes of endoscopic balloon dilatation in pediatric ES. The interval between surgery and the first EBD is another factor affecting response and the number of sessions of dilatation.

Core tip: In this study, we evaluated the safety, efficacy, and predictors of the outcome of endoscopic balloon dilatation treatment for strictures after esophageal atresia repair. We found that the diameter, length, and number of strictures were the most important predictive factors for successful endoscopic balloon dilatation treatment for anastomotic esophageal strictures. An earlier dilation after 4 wk of surgery contributed to a better response and fewer dilation sessions.

- Citation: Dai DL, Zhang CX, Zou YG, Yang QH, Zou Y, Wen FQ. Predictors of outcomes of endoscopic balloon dilatation in strictures after esophageal atresia repair: A retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(10): 1080-1087

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i10/1080.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i10.1080

Benign esophageal stricture (ES) is a problem that pediatric gastroenterologists often encounter. ESs in children may develop from esophageal surgery and congenital constriction or as a result of caustic injury and esophagitis caused by gastro-esophageal reflux[1-3]. This condition can result in the clinical syndromes of persistent nonbilious vomiting and dysphagia, and the most common clinical consequences are malnutrition and failure to thrive in children[4].

Treatment for this condition is critical since it may cause high morbidity associated with failure to thrive and high aspiration risks. The aim of treatment is to ease the symptoms, improve the patient’s nutritional status, and prevent complications. Recently, some studies reported the advantages and safety of balloon dilatation in the treatment of benign ES in children[5,6]. Balloon dilatation has been the first line of therapy in the majority of patients[7,8] due to the high rate of success and low complication and mortality rates[9]. With advances in endoscopic techniques, endoscopic balloon dilatation (EBD) has recently become the first line of therapy for benign ESs. The present study aimed to evaluate the response, safety, and factors predicting the outcome of EBD treatment for ESs, by retrospectively examining the records of pediatric patients who underwent the procedure.

We had access to identifying information during and after data collection. The Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Children’s Hospital approved the analysis (Register number: SZCH [article] 2019(012)) and waived the need for informed consent. The study was carried out in accordance with principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The medical records of 64 pediatric patients under 18 years of age who were treated by EBD for anastomotic stricture after thoracoscopic esophageal atresia repair in Shenzhen Children's Hospital from January 2012 to December 2016 were investigated retrospectively.

All the patients were diagnosed with benign ES based on their detailed histories as obtained from their parents, clinical presentation, physical examination, upper gastrointestinal radiography, and endoscopic appearance. The diameter and length of the strictures were determined according to an esophagogram. A dysphagia scoring system was applied to assess the dysphagia and the scores scaled from 0 to 4: 0, no dysphagia; 1, unable to swallow certain solids; 2, able to swallow soft foods; 3, able to swallow only liquids; and 4, unable to swallow even liquids. Complete remission and relief of symptoms or dysphagia score ≤ 1 were considered effective responses. The follow-up time ranged from 36 mo to 60 mo. The demographic features, features of the strictures, and outcomes were recorded. The response, complication, and recurrence rates were comparatively evaluated, and the risk factors were analyzed.

After written consent was obtained from the children’s parents, endoscopy and dilatation were performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. First, a controlled radial expansion wire-guided balloon dilator (Boston Scientific, Cork, Ireland) was introduced and positioned across the stricture under the direct guidance of an endoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Then, the balloon was inflated with saline to achieve the desired pressure, which was maintained for 1 min. Two to three three-minute multistep inflations with incremental size balloons were used in each dilatation session. The length of the balloon is 5.5 cm, and the diameters range from 6 mm to 18 mm. The balloon (Boston Scientific, Cork, Ireland. REF: M0058390, M0058400, M0058410, M0058420) was chosen according to the clinical condition of the patient and endoscopic appearance of the stricture. A balloon with a minimum inflated diameter 2 mm more than the stricture diameter was determined by clinical assessment.

All patients were followed as outpatients after successful dilatation. The interval between EBD sessions was 4-8 wk if symptoms of obstruction were present and thereafter was decided mainly according to radiology or endoscopy evaluation.

The treatment effect was evaluated based on improvement of symptoms or dysphagia score before the first dilation and after the final dilation. We defined failure as no alteration of the diameter of the stricture to dilation. Non-effectiveness was determined if the clinical symptom of dysphagia persisted until the tenth dilation. Recurrence was considered if a relapse of symptoms occurred within 1 year after the last procedure.

Statistical presentation and analyses were conducted using means, standard deviations, Student’s t-test, and the chi-squared test by SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Student’s t-test was used for comparisons between groups; the chi-square test was used to study the association between two variables or the comparison between two independent groups with regard to the categorized data; if there were two or more groups, the analysis of variance was applied. Spearman rank order correlation analysis for nonparametric correlations was applied to test correlations between variables. A probability of error (P value) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sixty-four children were diagnosed with ES in this study (median age, 5.45 mo; female/male ratio, 30/34). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 64), n (%) | |

| Sex | Male | 34 (53.1) |

| Female | 30 (46.9) | |

| Age at surgery (h) | Median 3.15 (2.89-6.17) | |

| Body weight at operation (kg) | Median 2.73 (1.62-3.55) | |

| Post-repair complications | Gastroesophageal reflux | 31 (48.4) |

| Anastomotic leakage | 8 (12.5) | |

| Recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula | 3 (4.7) | |

| Tracheomalacia | 2 (3.1) | |

| Vocal cord paralysis | 0 (0) | |

| Stricture length | ≤ 2 cm | 14 (21.9) |

| 2-5 cm | 42 (65.6) | |

| ≥ 5 cm | 8 (12.5) | |

| Number of strictures | Single | 58 (90.6) |

| Multiple | 6 (9.4) | |

| Location of stricture | Upper third esophageal | 10 (15.6) |

| Middle third esophageal | 24 (37.5) | |

| Lower third esophageal | 30 (46.9) | |

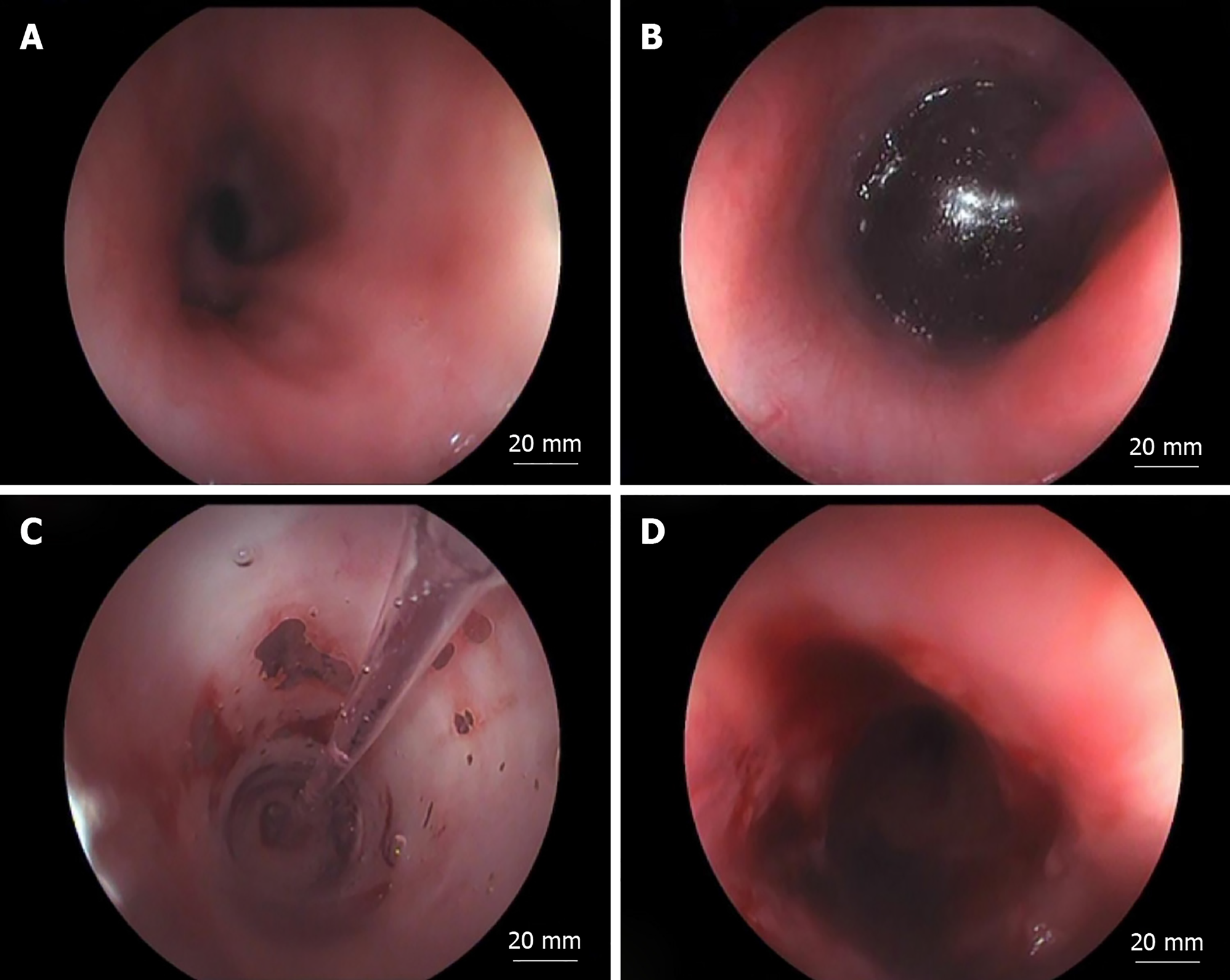

As shown in Table 1, most patients had a single stricture with a length of 2-5 cm. The most frequently involved site was the lower third of the esophagus. Compared to the diameter before the initial dilation, the diameter of the stricture was significantly greater after the final session of EBD (P = 0.014). Figure 1 shows an esophageal stricture in endoscopic view before and after dilation.

A total of 132 sessions were performed for the 64 patients, ranging from one to six sessions per patient. Two cases failed and underwent surgery. Of the patients with successful management, 96.77% had symptom remission. All the children with effective treatment were fed a solid or semiliquid diet. Improvement in nutrition and in failure to thrive was achieved. Relapse of symptoms occurred in two patients who received additional treatment by renewed EBD and are currently under follow-up. None of the patients died during the follow-up period after EBD. The outcomes of the EBD procedure are presented in Table 2.

| Outcome | Results (n = 64) | ||

| Age at first EBD (mo) | 5.45 ± 0.31 | ||

| Interval1 (mo) | 5.43 ± 0.29 | ||

| Sessions | 2.19 ± 0.24 | ||

| Follow-up (mo) | 42.88 ± 14.30 | ||

| Diameter (mm) | Before first EBD | 2.93 ± 0.37 | |

| After final EBD | 10.05 ± 0.34 | ||

| P value | 0.014 | ||

| Success | Success | 62 (96.9%) | |

| Failure | 2 (3.1%) | ||

| Complications | Perforation | 4 (6.45%) | |

| Bleeding | 2 (3.23%) | ||

| Reflux esophagitis | 1 (1.61%) | ||

| Infection | 1 (1.61%) | ||

| Multiple | 2 (3.23%) | ||

| Total | 5 (8.06%) | ||

| No complications | 57 (91.9%) | ||

| Response | Effective | Remission | 54 (87.10%) |

| Relief | 6 (9.68%) | ||

| Total | 60 (96.77%) | ||

| Ineffective | 2 (3.23%) | ||

| Recurrence | No relapse | 58 (96.67%) | |

| Relapse | 2 (3.33%) | ||

The most common complications in this study included esophageal perforation, bleeding, infection, and severe gastroesophageal reflux. Multiple complications occurred in two patients. One suffered perforation, aspiration, severe reflux esophagitis, and infection, and the other suffered perforation and infection. All the patients with complications healed under conservative treatment as follows: Pharyngeal suction, parenteral nutrition, systematic intravenous antibiotherapy, and antireflux medications. The patients suffered severe gastroesophageal reflux requiring treatment with omeprazole for antireflux and with domperidone as a dynamic drug for 2 wk to 2 mo.

The predictive factors for the outcomes of EBD are summarized in Table 3. More complications and sessions were seen in the patients with more than one stricture site (P = 0.010 and 0.003, respectively) and in patients with a smaller diameter of strictures (P = 0.010 and 0.013, respectively). The length of the stricture was significantly associated with complications of EBD (P = 0.001). Moreover, a longer interval between surgery and the first EBD was related to more EBD sessions and a poorer response (P = 0.000 and 0.019). The factors predicting outcomes of endoscopic balloon dilatation treatment is shown in Table 4. The correlations between risk factors and outcomes in patients with anastomotic esophageal strictures is shown in Table 5.

| Out-comes | Length | Number of strictures | Sessions | ||||||||||

| ≤ 2 cm, n = 42 | 2-5 cm, n = 14 | ≥ 5 cm, n = 8 | Statistic value | P value | Single, n = 58 | Multiple, n = 6 | Statistic value | P value | ≤ 2, n = 46 | > 2, n = 18 | Statistic value | P value | |

| Complications (n) | 0 | 2 | 3 | χ2 = 13.025 | 0.001 | 2 | 3 | OR = 14.5 | 0.004 | 3 | 2 | OR = 0.587 | 0.615 |

| Respon-se (score) | -2.21 ± 0.51 | -2.17 ± 0.39 | -2.17 ± 0.43 | F = 1.431 | 0.313 | -2.18 ± 0.41 | -2.15 ± 0.65 | F = 2.178 | 0.180 | -2.21 ± 0.52 | -2.19 ± 0.47 | F = 3.211 | 0.487 |

| Recurr-ence (n) | 0 | 0 | 2 | χ2 = 8.802 | 0.012 | 1 | 1 | OR = 9.667 | 0.180 | 1 | 1 | OR = 0.391 | 0.487 |

| Sessions (mean ± SD) | 1.95 ± 0.28 | 2.57 ± 0.43 | 2.75 ± 0.62 | F = 1.729 | 0.416 | 2.04 ± 0.22 | 4.12 ± 0.67 | F = 6.797 | 0.014 | ||||

| Outcome | Interval1 (mo) | Sessions | Length (cm) | Diameter before EBD (cm) | ||||

| Coefficient | P value | Coefficient | P value | Coefficient | P value | Coefficient | P value | |

| Complications | 0.324 | 0.587 | 0.006 | 0.858 | 0.616 | 0.031 | 0.724 | 0.012 |

| Response | -0.527 | 0.024 | -0.019 | 0.672 | -0.324 | 0.437 | -0.319 | 0.346 |

| Recurrence | 0.162 | 0.453 | 0.135 | 0.446 | 0.255 | 0.615 | 0.151 | 0.627 |

| Sessions | 0.338 | 0.017 | -0.312 | 0.411 | 0.612 | 0.031 | ||

In this study, the majority of the 64 patients had one stricture. The success rate of EBD (96.9%) in this study is higher than that reported in the literature[10]. The number of EBDs ranged from one to six sessions per patient (median: 2.19), which was much lower than the median five sessions per patient reported by Cakmak[5]. We speculated that our overall high success rate and relatively fewer median EBD sessions were partially due to the sufficient assessment and preparation before EBD, technical considerations, and the optimal choice of balloon size.

The complication rate associated with EBD treatment of benign ES is approximately 13.2%[5]. The response rates have been reported to be between 16% and 80%[11,12]. Recurrence was previously reported in 31.6% of patients after EBD treatment[5]. In our study, the complication rate was 8.06%. The effective response rate was 96.77%. Only two patients developed recurrence and required renewed EBD. The results of this study indicated that EBD was an effective alternative treatment with a low restenosis rate for ES in children.

The success rate of EBD is reduced in cases of long-segment stenoses[13,14]. The greater the length of the stricture, the more times of EBD is needed[6]. The complication rate was as high as 37.5% in cases that had strictures longer than 5 cm[5]. We found a significant impact of stricture length on complications in this study, but it had no impact on success rate or the number of EBD sessions. The diameter and number of strictures significantly affected the complications and the number of EBD sessions, but did not affect the success rate, efficacy, or recurrence rate. More complications and more sessions were seen in patients with multiple strictures and/or small strictures. It was considered that the lumen tortuosity, deformation, and diverticulisation contributed to the adverse impact on endoscopic procedures and resulted in more complications. Moreover, a substantially higher shear force was necessary to achieve the same expected diameter using a small balloon than a larger balloon, for example, a 10 atm force was needed to obtain a same diameter of 8 mm when using a 6-7-8 mm balloon while only a 3 atm force was needed when using an 8-9-10 mm balloon. More shearing force was exerted on the esophagus in patients with small diameter strictures.

We further found that the key predictor of EBD sessions was the interval between surgery and the first EBD. An early EBD was related to fewer EBD sessions. Similar to the findings from some published studies on patients with caustic ESs, early EBD has a positive impact on treatment success[15].

EBD was suggested not to be performed more than twice in view of the failure of treatment[16,17], increased risk of complications, and loss of time[18]. When the patients were divided into two groups according to the number of EBD sessions (≤ 2 and > 2), patients with more than two EBD sessions did not have a significantly higher risk of failure or complications compared to patients with two or fewer sessions in this study (P > 0.05). Gender was not a risk factor for outcomes of EBD in patients with ES in this study.

The shortcomings of our study include the relatively short follow-up period and the small sample sizes of the subgroups.

In conclusion, this study indicated that the diameter and number of strictures are the most crucial predictive factors for complications and the number of dilatation sessions. Stricture length is the main risk factor for complications of EBD. An early EBD after surgery is related to a better response and fewer EBD sessions.

Endoscopic balloon dilatation (EBD) has become the first line of therapy for benign esophageal strictures (ESs); however, there are few studies on the predictive factors for outcomes of EBD treatment for anastomotic strictures after esophageal atresia (EA) repair in pediatric patients.

We aimed to perform a retrospective cohort analysis to help choose the optimal time for EBD treatment for anastomotic strictures after EA repair in pediatric patients.

Our analysis aimed to evaluate the response, safety, and predictive factors for the outcome of EBD treatment for ESs.

This is a monocentric retrospective cohort analysis. Patients treated by EBD for benign stricture after thoracoscopic EA repair in Shenzhen Children's Hospital from January 2012 to December 2016 were included. The demographic features, characteristics of the strictures, and outcomes were recorded. The response, complications, and recurrence rates were comparatively evaluated, and the risk factors were analyzed.

The number of dilatation sessions and complications were significantly greater in patients with smaller diameter strictures and with more than one stricture. The length of the stricture was significantly associated with complications of EBD. A longer interval between surgery and the first dilatation was related to more sessions and a poorer response.

The diameter, length, and number of strictures are the most important factors for the clinical outcomes of EBD in strictures after EA repair. The interval between surgery and the first EBD is a key factor for response and the number of sessions of dilatation.

Future studies analyzing safety and factors for the outcome of EBD treatment should focus on a comparison between strictures of different etiologies.

The authors wish to thank the patients and their families for allowing us to use the medical documentation and information leading to the present article, and we wish to thank Dr. Wei-Guo Cao (MD, Radiologist, Radiology Department of Shenzhen Children's Hospital) for technical assistance with the imaging.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aydin M, Ciccone MM, Gallo G, Kasirga E S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Broor SL, Lahoti D, Bose PP, Ramesh GN, Raju GS, Kumar A. Benign esophageal strictures in children and adolescents: etiology, clinical profile, and results of endoscopic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:474-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shah MD, Berman WF. Endoscopic balloon dilation of esophageal strictures in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Allmendinger N, Hallisey MJ, Markowitz SK, Hight D, Weiss R, McGowan G. Balloon dilation of esophageal strictures in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:334-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Baird R, Laberge JM, Lévesque D. Anastomotic stricture after esophageal atresia repair: a critical review of recent literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:204-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cakmak M, Boybeyi O, Gollu G, Kucuk G, Bingol-Kologlu M, Yagmurlu A, Aktug T, Dindar H. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of benign esophageal strictures in childhood: a 15-year experience. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chang CF, Kuo SP, Lin HC, Chuang CC, Tsai TK, Wu SF, Chen AC, Chen W, Peng CT. Endoscopic balloon dilatation for esophageal strictures in children younger than 6 years: experience in a medical center. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011;52:196-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Antoniou D, Soutis M, Christopoulos-Geroulanos G. Anastomotic strictures following esophageal atresia repair: a 20-year experience with endoscopic balloon dilatation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:464-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yusuf TE, Brugge WR. Endoscopic therapy of benign pyloric stenosis and gastric outlet obstruction. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:570-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akarsu C, Unsal MG, Dural AC, Kones O, Kocatas A, Karabulut M, Kankaya B, Ates M, Alis H. Endoscopic balloon dilatation as an effective treatment for lower and upper benign gastrointestinal system anastomotic stenosis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:138-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alshammari J, Quesnel S, Pierrot S, Couloigner V. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of esophageal strictures in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75:1376-1379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuwada SK, Alexander GL. Long-term outcome of endoscopic dilation of nonmalignant pyloric stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:15-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hamzaoui L, Bouassida M, Ben Mansour I, Medhioub M, Ezzine H, Touinsi H, Azouz MM. Balloon dilatation in patients with gastric outlet obstruction related to peptic ulcer disease. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2015;16:121-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schlegel RD, Dehni N, Parc R, Caplin S, Tiret E. Results of reoperations in colorectal anastomotic strictures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1464-1468. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Stienecker K, Gleichmann D, Neumayer U, Glaser HJ, Tonus C. Long-term results of endoscopic balloon dilatation of lower gastrointestinal tract strictures in Crohn's disease: a prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2623-2627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Uygun I, Aydogdu B, Okur MH, Arayici Y, Celik Y, Ozturk H, Otcu S. Clinico-epidemiological study of caustic substance ingestion accidents in children in Anatolia: the DROOL score as a new prognostic tool. Acta Chir Belg. 2012;112:346-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Perng CL, Lin HJ, Lo WC, Lai CR, Guo WS, Lee SD. Characteristics of patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction requiring surgery after endoscopic balloon dilation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:987-990. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Boylan JJ, Gradzka MI. Long-term results of endoscopic balloon dilatation for gastric outlet obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1883-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Boybeyi O, Karnak I, Ekinci S, Ciftci AO, Akçören Z, Tanyel FC, Senocak ME. Late-onset hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: definition of diagnostic criteria and algorithm for the management. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1777-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |