Published online Apr 7, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i13.1410

Peer-review started: December 6, 2017

First decision: January 18, 2018

Revised: February 21, 2018

Accepted: March 3, 2018

Article in press: March 3, 2018

Published online: April 7, 2018

Processing time: 118 Days and 21.1 Hours

To investigate potential triggering factors leading to acute liver failure (ALF) as the initial presentation of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).

A total of 565 patients treated at our Department between 2005 and 2017 for histologically-proven AIH were retrospectively analyzed. However, 52 patients (9.2%) fulfilled the criteria for ALF defined by the “American Association for the Study of the Liver (AASLD)”. According to this definition, patients with “acute-on-chronic” or “acute-on-cirrhosis” liver failure were excluded. Following parameters with focus on potential triggering factors were evaluated: Patients’ demographics, causation of liver failure, laboratory data (liver enzymes, MELD-score, autoimmune markers, virus serology), liver histology, immunosuppressive regime, and finally, outcome of our patients.

The majority of patients with ALF were female (84.6%) and mean age was 43.6 ± 14.9 years. Interestingly, none of the patients with ALF was positive for anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody (LKM). We could identify potential triggering factors in 26/52 (50.0%) of previously healthy patients presenting ALF as their first manifestation of AIH. These were drug-induced ALF (57.7%), virus-induced ALF (30.8%), and preceding surgery in general anesthesia (11.5%), respectively. Unfortunately, 6 out of 52 patients (11.5%) did not survive ALF and 3 patients (5.7%) underwent liver transplantation (LT). Comparing data of survivors and patients with non-recovery following treatment, MELD-score (P < 0.001), age (P < 0.05), creatinine (P < 0.01), and finally, ALT-values (P < 0.05) reached statistical significance.

Drugs, viral infections, and previous surgery may trigger ALF as the initial presentation of AIH. Advanced age and high MELD-score were associated with lethal outcome.

Core tip: Autoimmune hepatitis is considered to manifest as a chronic disease. In few cases, the clinician is challenged with patients revealing acute liver failure as their first manifestation of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). The aim of our study was to investigate features of especially these patients with focus on potential triggering factors. We identified triggering factors in half of our patients (26 out of 52 patients with acute liver failure within a total cohort of 565 AIH patients). These were drugs, viral infections, and surgery. Advanced age and high MELD-score were associated with lethal outcome. Consequently, the clinician would be well-advised to document these underlying conditions.

- Citation: Buechter M, Manka P, Heinemann FM, Lindemann M, Baba HA, Schlattjan M, Canbay A, Gerken G, Kahraman A. Potential triggering factors of acute liver failure as a first manifestation of autoimmune hepatitis-a single center experience of 52 adult patients. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(13): 1410-1418

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i13/1410.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i13.1410

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a complex disease characterized by immune-mediated destruction of hepatic parenchyma, female gender bias, presence of auto-antibodies, hypergammaglobulinaemia, association with other autoimmune conditions, and excellent response to immunosuppressive therapy[1]. Since its first description by Waldenström in the early 1950’s, AIH was considered to manifest as a chronic liver disease and its fulminant presentation was not commonly reported[2-4]. Over the last decades, it has become apparent that AIH can occur with diverse clinical phenotypes and its classical perception of a chronic inflammatory liver disease that affects mainly young Caucasian women has been expanded[5-8].

However, approximately 20%-30% of the patients reveal an acute presentation which may be induced by a triggering agent such as previous viral infections, toxic injury or treatment with immune-modifying drugs. Infectious triggers are commonly indicated as being involved in the induction of autoimmune diseases, with Epstein-Barr (EBV) or Cytomegalovirus (CMV) being implicated in several autoimmune liver disorders, such as type I autoimmune hepatitis or primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)[9]. A remarkable proportion of patients with acute manifestation can develop acute liver failure (ALF), particularly in case of delayed diagnosis and treatment[4,10,11].

ALF is characterized by a rapid onset of severe hepatocyte injury without prior liver disease that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality[12,13]. The most widely accepted definition of ALF includes evidence of coagulation abnormality, usually an INR ≥ 1.5, and any degree of mental alteration (hepatic encephalopathy) in a patient without pre-existing chronic liver disease with an illness of < 26 wk duration[14].

Patients with AIH-induced ALF are frequently difficult to diagnose due to absence of serological markers including anti-nuclear (ANA), anti-smooth muscle (SMA), anti-liver kidney microsomal (LKM) antibodies, and normal immunoglobulin G (IgG)-levels in numerous cases[15,16]. In this setting, determination of major histocompatibility complex HLA-loci (e.g., HLA-DR3 and -DR4), which are reported to have a strong association with AIH, might be helpful additional diagnostic tools[1,8,17].

In the daily clinical setting, the hepatologist is frequently faced with patients having unknown elevations of their liver enzymes for years or even decades. Most of these asymptomatic patients present only marginal increased liver enzymes with normal liver function. Routine work-up of these cases leads finally to the diagnosis of underlying AIH and - following steroid therapy - transaminases often return to normal ranges. However, in few cases, one is challenged with patients previously being healthy without any signs of hepatopathy but rapidly demonstrating a life-threatening acute liver failure as their first manifestation of AIH with the necessity of urgent organ transplantation. Therefore, the aim of our study was to investigate demographic characteristics and clinical course of especially these patients presented with ALF as their initial presentation of AIH with special focus on potential triggering factors which may activate the “autoimmune machinery” leading to onset of the disease.

In this retrospective study between 01/2005 and 04/2017, a total of 565 patients with histologically-proven AIH were analyzed, from whom 52 previously healthy patients suffered from ALF as their initial presentation of autoimmune hepatitis. According to the criteria defined by the “American Association for the Study of the Liver (AASLD)”, ALF was diagnosed by elevation of liver enzymes in combination with hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and coagulopathy (INR > 1.5) in the absence of a pre-existing chronic liver disease[14]. AIH was diagnosed according to the “Diagnostic Scoring System of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group” including analysis of auto-antibodies, IgG-levels, histological features, and exclusion of viral markers[18,19]. Liver histology was available for the whole study population and was obtained either by percutaneous- or laparoscopy-guided biopsy (Figure 1A and B). Only adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) were included in the study. The University Clinic of Essen ethics committee approved the retrospective, anonymous analysis of the data and the study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their written informed consent prior to study inclusion.

At initial presentation, alanine-aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin, serum creatinine, INR, IgG, IgM, γ-globulins, antibody profile (ANA, AMA, ANCA, SMA, LKM, SLA), and finally, HLA-loci (HLA- A1, -B8, -DR3, and -DR4) were analyzed. Each patient was also tested for viral markers (anti-HAV IgM, HBs-Ag, anti-HBc IgM, HBeAg, anti-HBe, anti-HBs, anti-HCV, anti-HDV-EIA, anti-HEV IgM, and PCR’s for HBV, HCV, HEV, HSV, CMV, EBV), transferrin-saturation, ceruloplasmin, copper in serum, soluble interleukin-II receptor, α1-antitrypsin, and finally, GLDH. In suspected cases of Wilson’s disease, additional examinations were performed (Kayser-Fleischer ring, copper in urine, parameters of hemolysis, and also determination of cupper in the liver biopsy).

The appropriate diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) vs DILI-AIH involves the collection of historical and laboratory data, including the latency in onset, the rate of resolution after discontinuing treatment, and exclusion of other reasonable causes of liver injury. The advantage of the RUCAM instrument is that it is systematic, thorough, and objective. We therefore used this instrument in our study population as - at present - it is considered the best method for assessing causality in DILI.

Liver biopsy was performed in all patients with evidence of typical histopathological features of AIH, namely presence of interface hepatitis, lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltration exceeding the borders of the portal tract, emperipolesis, and rosette formations, respectively. Differentiating between drug-induced ALF and AIH-induced ALF is difficult on the basis of histology alone. In both cases plasma cell rich inflammation with interface hepatitis can be present. In order to differentiate DILI from AIH clinical, historical, and laboratory data have to be considered. If EBV, CMV or HEV infection was suspected, viral detection by means of immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and PCR was also performed.

After diagnosis of AIH-induced ALF, each patient received standard steroid therapy (1 mg per kg body weight/d) intravenously with consecutive down-tapering to a maintenance dose of 7.5 mg daily. Non-recovery was defined as death or liver transplantation (LT) within 28 d despite steroid treatment and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy with azathioprine.

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism, version 6.00 for MacOsX (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States). For descriptive statistics medians and IQR were determined. All variables were tested for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, the Shapiro-Wilk test, and calculation of skew and kurtosis. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare differences between independent groups. Categorical data were tested with the chi-square test and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The whiskers used in the graphs extend down to the 5th percentile and up to the 95th percentile.

Fifty-two out of 565 patients with AIH suffered from ALF as their initial presentation (9.2%) (Figure 1A and B) and were included in the study. Mean age of the study population was 43.6 ± 14.9 (19-76) years while the majority was of female gender (44/52, 84.6%). Laboratory parameters with median values on admission were as follows: ALT: 1391.0 (843.5-2154.5) U/L, total bilirubin: 14.3 (11.7-18.7) mg/dL, serum creatinine: 0.76 (0.55-0.95) mg/dL, INR: 1.78 (1.64-2.00), immunoglobulin G: 17.2 (13.1-22.8) g/L, and finally, γ-globulin-fraction: 24.5% (19.5%-29.3%). Calculated median labMELD-score was 24 (22-26) points. All patients with AIH-induced ALF received a pulse therapy with steroids starting with 1 mg/kg body weight intravenously. A total of 30 patients (57.7%) continued steroids in a daily dose of 7.5 mg to maintain remission. Azathioprine (in 27 patients, 51.9%) and also cyclosporine A (in 7 patients, 13.5%) were also used to maintain remission. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) was classified using the West Haven criteria. We found HE grade I in 46 of our 52 patients (88.4%), HE grade II in 2 patients, HE grade III in 2 patients, and finally, HE grade IV in 2 further patients, respectively. Unfortunately, patients with HE grade IV had poor prognosis and died of acute liver failure. We found no correlation between grade of HE and antibody or HLA-profiles. Moreover, we also did not found a correlation between the triggering factors with severity of HE (data nor shown). Patients’ demographics and laboratory data are summarized in Table 1.

| Study population (n = 52) with AIH-induced ALF | |

| Mean age (yr) | 43.6 ± 14.9 (19-76) |

| Male | 8 (15.4%) |

| Female | 44 (84.6%) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Grade I: 46/52 (88.4%) |

| Grade II: 2/52 (3.8%) | |

| Grade III: 2/52 (3.8%) | |

| Grade IV: 2/52 (3.8%) | |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | Steroid induction: 52/52 (100%) |

| Steroid maintenance: 30/52 (57.7%) | |

| Steroid withdrawal: 20/52 (42.3%) | |

| Azathioprine: 27/52 (51.9%) | |

| Cyclosporine A: 7/52 (13.5%) | |

| ALT (U/L) | 1391.0 (843.5-2154.5) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 14.3 (11.7-18.7) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.76 (0.55-0.95) |

| INR | 1.78 (1.64-2.00) |

| LabMELD-score | 24 (22-26) |

| Immunoglobulin G (g/L) | 17.2(13.1-22.8) |

| γ-globulin-fraction (%) | 24.5 (19.5-29.3) |

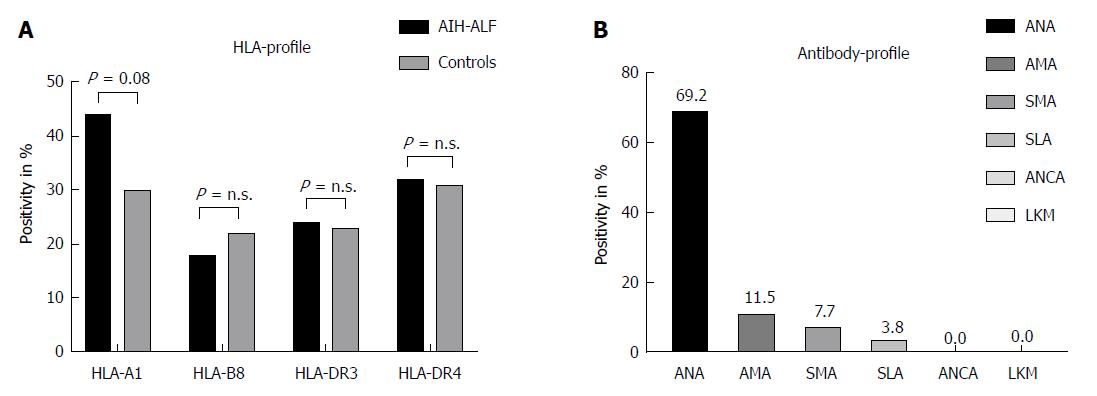

Thirty-six out of 52 patients were positive for ANA (69.2%), 6/52 for AMA (11.5%), 4/52 for SMA (7.7%), and 2/52 for SLA (3.8%), respectively. Interestingly, none of the adult patients with acute liver failure was either positive for ANCA or LKM. Data on HLA-loci were available for 34 patients (65.4%) showing the following results: HLA-A1 positivity in 15/34 (44.1%), HLA-B8 in 6/34 (17.6%), HLA-DR3 in 8/34 (23.5%), and HLA-DR4 in 11/34 patients (32.4%). HLA- and antibody profiles of our study population are demonstrated in Figure 2A and B.

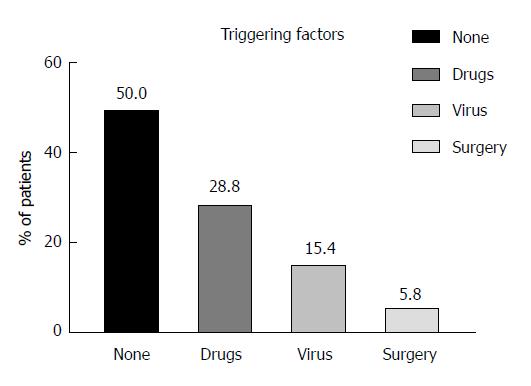

We could identify potential triggering factors for ALF in patients with their first manifestation of AIH in 26/52 patients (50.0%). These triggers were predominantly drugs [15/26 (57.7%), namely non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) (n = 8), antibiotics (n = 5), ipilimumab (n = 1), and rivaroxaban (n = 1)] followed by previous acute viral infections [8/26 (30.8%), namely Epstein-Barr virus (n = 4), Cytomegalovirus (n = 3), and hepatitis E virus (n = 1)]. Finally, the remaining 3 patients underwent previous surgery in general anesthesia (11.5%) (Figure 3).

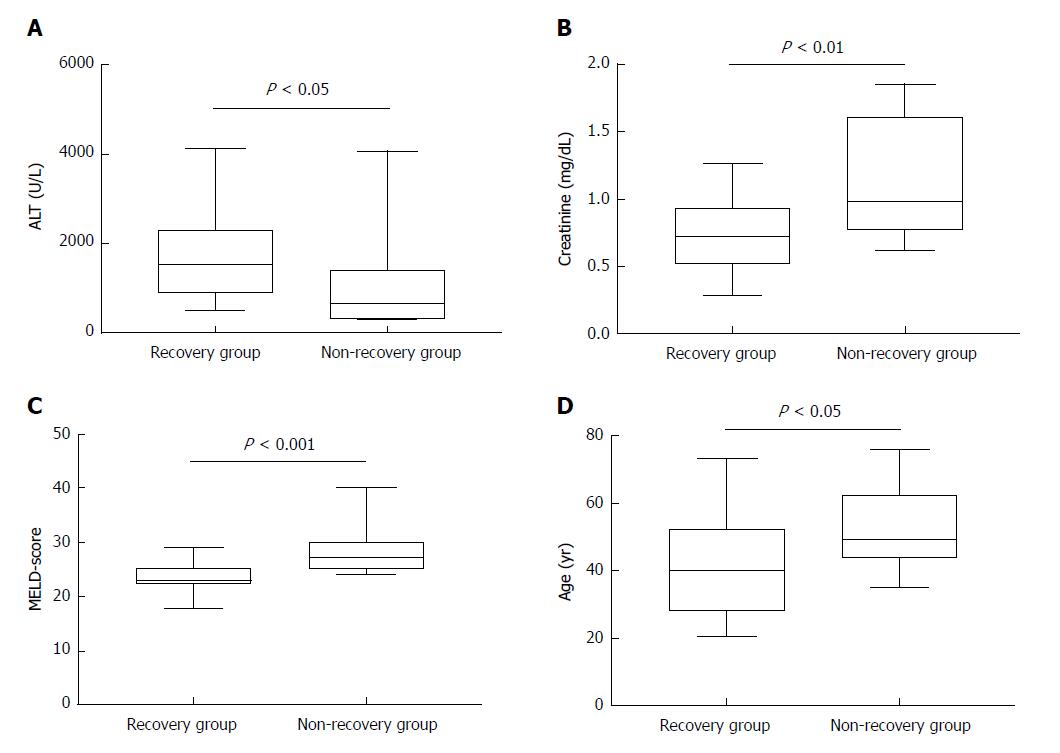

Unfortunately, 6 out of 52 patients did not receive an organ offer and died due to ALF while 3 further patients underwent liver transplantation (non-recovery group). When comparing data of these patients with patients who responded to steroids and survived ALF (recovery group), statistical analysis revealed significant differences in terms of age [median age: 40.0 (28.0-52.0) years for the recovery group vs median age: 49.0 (44.0-62.5) years, for the non-recovery group, P = 0.031], serum creatinine [median for the recovery group: 0.72 (0.51-0.92) mg/dL vs median for the non-recovery group: 0.98 (0.77-1.61) mg/dL, P = 0.0069], labMELD-score [median for the recovery group: 23 (22-25) vs median for the non-recovery group: 27 (25-30), P = 0.0007, and finally, median ALT-values for the recovery group 1512 (904-2276) U/L vs median for the non-recovery group: 711 (324-1391) U/L, P = 0.0157) (Table 2 and Figure 4A-D). None of the remaining AIH patients of our cohort (n = 513 patients) developed acute liver failure under therapy with corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive therapy. However, no significance was found for markedly increased bilirubin levels comparing both groups.

| Recovery (n = 43) | Non-recovery (n = 9) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 40.0 (28.0-52.0) | 49.0 (44.0-62.5) | 0.031 |

| Male/female | 7/36 | 1/8 | NS |

| ALT (U/L) | 1512 (904-2276) | 711 (324-1391) | 0.0157 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 14.0 (11.3-18.7) | 16.1 (11.8-23.6) | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.72 (0.51-0.92) | 0.98 (0.77-1.61) | 0.0069 |

| INR | 1.76 (1.63-1.98) | 1.96 (1.75-2.79) | 0.0644 |

| LabMELD-score | 23 (22-25) | 27 (25-30) | 0.0007 |

The etiology of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is uncertain but - in some cases - the disease can be triggered by external factors such as viruses or drugs. AIH usually develops in individuals with genetic background. Many drugs have been linked to AIH phenotypes, which sometimes persist after drug discontinuation, suggesting that they awaken latent autoimmunity. Growing information on the relationship of drugs and AIH is being available, being drugs and biologic agents more frequently involved in cases allowing to establish a causal relationship[20-23]. According to current literature, the frequency of patients with drug-induced AIH (DILI-AIH) is reported to range from 9%-17% in overall patients diagnosed with AIH[24,25].

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is the most common cause of acute liver failure (ALF) and responsible for approximately 50% of the cases in the United States and Western Europe. DILI may be dose-dependent and predictable (e.g., acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity) or idiosyncratic, unpredictable, and probably independent of dose[12,26]. Autoimmune hepatitis - on the contrary - is a relatively rare cause of ALF in developed countries with an incidence of approximately 5%[27]. According to the “Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG)” registry, including 2436 patients between 1998 and 2016 in the United States, 163 (6.7%) were diagnosed with ALF due to AIH[28]. In our cohort 9.2% of AIH patients presented ALF. DILI is reported to have a phenotype of autoimmunity similar to AIH and distinguishing these entities still remains a challenge[29]. However, immune-mediated DILI nearly always resolves or becomes quiescent when drugs are withdrawn[24,30]. In contrast, in patients with drug-induced AIH, it can be assumed that predisposition for AIH existed before, but the disease was quiescent and remained undiagnosed until this drug triggered the autoimmune process. Recently, Licata and colleagues reported 12 patients from a series of 136 subjects with DILI that were diagnosed as drug-induced AIH (9%)[31]. Accordingly, Kuzu et al[32] described 82 DILI patients from whom five (6%) were diagnosed with DILI-AIH.

AIH - in its classical perception - commonly presents as a chronic hepatopathy. On the one hand, the majority of patients with AIH are diagnosed due to accidentally and repeatedly elevated liver enzymes in routine check-up examinations without having symptoms. On the other hand, AIH can lead to fulminant acute liver failure which is associated with high morbidity and mortality. The most important genetic risk factor is human leukocyte antigen, especially HLA-DR, whereas the role of environmental factors is not completely understood. Immunologically, disruption of the immune tolerance to autologous liver antigens may be a trigger of AIH. According to current data, triggering agents which may lead to this disruption are mainly unknown, but may include viral infections, environmental toxins, drugs, and vaccinations. There is growing evidence for a loss of immune tolerance to self-antigens playing a part in the development of this condition[33-38]. Genetic risk association studies have identified HLA loci for the development of disease and providing prognostic information[38,39]. Interestingly, when compared to published allele frequencies in healthy controls, HLA genotypes of our cohort did not reach statistical significance while only HLA-A1 status revealed a positive trend[40]. Moreover, none of our adult patients included in the analyses was diagnosed with LKM-positive AIH type 2. This observation matches with current literature: Kessler and colleagues, who analyzed 30 patients with fulminant hepatic failure as the initial presentation of acute AIH, found that only 3% were LKM-positive[3]. Likewise, di Giorgio et al[41] described 46 children with fulminant hepatic failure of autoimmune etiology, none was LKM-positive.

In this study, we aimed to check potential triggering factors which may lead to ALF as the initial presentation of AIH. However, in 50% of the patients, triggering factors for ALF as the initial presentation of AIH were suspected. These were predominantly drugs (e.g., NSAID and antibiotics), followed by previous viral infections, and surgery in general anesthesia, respectively. Non-recovery - defined as death or liver transplantation within 28 d - was found among 9/52 patients (17.3%). Reviewing current literature, results of non-recovery in patients with ALF due to AIH differ significantly and range from 10%-60%[3,41,42]. Risk factors for non-recovery among our patients were increase in age, MELD-score, and creatinine levels, while higher liver enzymes (ALT-values) were associated with improved spontaneous recovery. Our center previously demonstrated that high ammonia, low albumin, and low ALT-levels were associated with worse outcome in childhood acute liver failure[43]. From our long-time clinical experience in patients with acute liver failure, we observed that patients with high ALT-values recovered better than their counterparts with low ALT-values indicating that there is still functioning liver parenchyma despite the fact of acute liver injury. On the one hand, extreme inflammation may reflect less grade of already existing hepatic necrosis and higher proportion of vital hepatocytes while on the other hand, inflammation may increase the probability of response to immunosuppressive treatment.

In summary, approximately 9% of our patients were diagnosed with acute liver failure as their initial presentation of autoimmune hepatitis which may be potentially induced by drugs, viral infections, and surgery in general anesthesia. Consequently, the clinician would be well-advised to accurately document these underlying conditions. Increases of age, MELD-score, and creatinine levels may be risk factors for lethal outcome or need for urgent liver transplantation, while higher levels of transaminases come along with improved spontaneous recovery.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is generally considered to manifest as a chronic liver disease. So far, only limited data are available investigating patients presenting a fulminant acute liver failure as a first manifestation of this autoimmune disorder. The significance of our study was therefore to investigate the circumstances leading to acute liver failure and onset of autoimmune hepatitis.

In the daily clinical setting, the hepatologist is frequently faced with patients demonstrating only a mild elevation of their liver enzymes. Routine work-up of these cases leads finally to the diagnosis of underlying AIH. However, in few cases, one is challenged with patients without any signs of hepatopathy but rapidly developing a life-threatening acute liver failure (ALF) as their first manifestation of AIH. We here presented potential triggering factors which may activate the “autoimmune machinery” leading to ALF.

The main objective of the present study was to gather more information with focus on potential triggering factors leading to acute presentation of AIH with consecutive liver failure. The clinician would be well-advised to accurately document these underlying conditions.

In our retrospective cohort study we investigated patients with histologically-proven AIH and further analyzed the patients who presented acute liver failure. Patients’ demographics, laboratory data, immunosuppressive regime, histology, and outcome were documented and studied.

We were able to identify potential triggering factors in 26/52 (50.0%) of our previously healthy patients presenting ALF as their first manifestation of AIH. These were drug-induced (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics) ALF (57.7%), virus-induced (Epstein-Barr, Cytomegalovirus and HEV) ALF (30.8%), and surgery in general anesthesia (11.5%), respectively.

Approximately 9% of our patients were diagnosed with ALF as their initial presentation of AIH which may be potentially induced by drugs, viral infections, and surgery in general anesthesia. Consequently, the clinician would be well-advised to ask his patients for hepato-toxic drugs and accurately document these underlying conditions. Increases of age, MELD-score, and creatinine levels were associated with lethal outcome or need for urgent liver transplantation.

With our study and findings we hope to further attract the physician’s attention especially in cases of acute liver failure induced by autoimmune hepatitis. In some cases, these disorders may be triggered by drugs and hepato-tropic viruses. We hope that more studies investigating acute liver failure as a first manifestation of AIH will be available in future.

We thank Professor Dr. Gregory Gores from the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic Rochester (Minnesota, United States) for his valuable contribution and his permanent support. We also thank the anonymous Reviewers for his/her thoughtful and constructive examination of our manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Eshraghian A, Lei YC, McMillin MA S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Wang Q, Yang F, Miao Q, Krawitt EL, Gershwin ME, Ma X. The clinical phenotypes of autoimmune hepatitis: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2016;66:98-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | WALDENSTROM J. Liver, blood proteins and nutritive protein. Dtsch Z Verdau Stoffwechselkr. 1953;9:113-119. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kessler WR, Cummings OW, Eckert G, Chalasani N, Lumeng L, Kwo PY. Fulminant hepatic failure as the initial presentation of acute autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:625-631. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Mendizabal M, Marciano S, Videla MG, Anders M, Zerega A, Balderramo DC, Tisi Baña MR, Barrabino M, Gil O, Mastai R. Fulminant presentation of autoimmune hepatitis: clinical features and early predictors of corticosteroid treatment failure. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:644-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis: Current Status and Future Directions. Gut Liver. 2016;10:177-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 847] [Article Influence: 84.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lammert C, Loy VM, Oshima K, Gawrieh S. Management of Difficult Cases of Autoimmune Hepatitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Heneghan MA, Yeoman AD, Verma S, Smith AD, Longhi MS. Autoimmune hepatitis. Lancet. 2013;382:1433-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rigopoulou EI, Smyk DS, Matthews CE, Billinis C, Burroughs AK, Lenzi M, Bogdanos DP. Epstein-barr virus as a trigger of autoimmune liver diseases. Adv Virol. 2012;2012:987471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dhawan A. Acute liver failure in children and adolescents. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:278-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sonthalia N, Rathi PM, Jain SS, Surude RG, Mohite AR, Pawar SV, Contractor Q. Natural History and Treatment Outcomes of Severe Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:548-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2525-2534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 736] [Cited by in RCA: 845] [Article Influence: 70.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Reddy KR, Ellerbe C, Schilsky M, Stravitz RT, Fontana RJ, Durkalski V, Lee WM; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Determinants of outcome among patients with acute liver failure listed for liver transplantation in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:505-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Polson J, Lee WM; American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:1179-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 641] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Czaja AJ. Autoantibodies as prognostic markers in autoimmune liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2144-2161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bernal W, Ma Y, Smith HM, Portmann B, Wendon J, Vergani D. The significance of autoantibodies and immunoglobulins in acute liver failure: a cohort study. J Hepatol. 2007;47:664-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zachou K, Muratori P, Koukoulis GK, Granito A, Gatselis N, Fabbri A, Dalekos GN, Muratori L. Review article: autoimmune hepatitis -- current management and challenges. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:887-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Czaja AJ. Performance parameters of the diagnostic scoring systems for autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:1540-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1252] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Castiella A, Zapata E, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Drug-induced autoimmune liver disease: A diagnostic dilemma of an increasingly reported disease. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Watkins PB, Seeff LB. Drug-induced liver injury: summary of a single topic clinical research conference. Hepatology. 2006;43:618-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Alla V, Abraham J, Siddiqui J, Raina D, Wu GY, Chalasani NP, Bonkovsky HL. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by statins. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:757-761. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Grasset L, Guy C, Ollagnier M. Cyclines and acne: pay attention to adverse drug reactions! A recent literature review. Rev Med Interne. 2003;24:305-316. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, Kamath PS, Takahashi N, Sanderson S, Neuhauser M, Lindor K. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2040-2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Castiella A, Lucena MI, Zapata EM, Otazua P, Andrade RJ. Drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis: a diagnostic challenge. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2501-2502; author reply 2502-2503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee WM, Squires RH Jr, Nyberg SL, Doo E, Hoofnagle JH. Acute liver failure: Summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2008;47:1401-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 566] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tujios SR, Lee WM. Acute liver failure induced by idiosyncratic reaction to drugs: Challenges in diagnosis and therapy. Liver Int. 2018;38:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | de Boer YS, Kosinski AS, Urban TJ, Zhao Z, Long N, Chalasani N, Kleiner DE, Hoofnagle JH; Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Features of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Patients With Drug-induced Liver Injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:103-112.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liu ZX, Kaplowitz N. Immune-mediated drug-induced liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:755-774. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Licata A, Maida M, Cabibi D, Butera G, Macaluso FS, Alessi N, Caruso C, Craxì A, Almasio PL. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: a retrospective cohort study. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:1116-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Kuzu UB, Öztaş E, Turhan N, Saygili F, Suna N, Yildiz H, Kaplan M, Akpinar MY, Akdoğan M, Kaçar S. Clinical and histological features of idiosyncratic liver injury: Dilemma in diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:277-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Aizawa Y, Hokari A. Autoimmune hepatitis: current challenges and future prospects. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:9-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Maggiore G, Nastasio S, Sciveres M. Juvenile autoimmune hepatitis: Spectrum of the disease. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:464-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Pischke S, Iking-Konert C. Hepatitis E infections in rheumatology. A previously underestimated infectious disease? Z Rheumatol. 2015;74:731-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lauletta G, Russi S, Pavone F, Marzullo A, Tampoia M, Sansonno D, Dammacco F. Autoimmune Hepatitis: Factors Involved in Initiation and Methods of Diagnosis and Treatment. Crit Rev Immunol. 2016;36:407-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | van Gemeren MA, van Wijngaarden P, Doukas M, de Man RA. Vaccine-related autoimmune hepatitis: the same disease as idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis? Two clinical reports and review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Arndtz K, Hirschfield GM. The Pathogenesis of Autoimmune Liver Disease. Dig Dis. 2016;34:327-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Webb GJ, Hirschfield GM. Using GWAS to identify genetic predisposition in hepatic autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2016;66:25-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Maiers M, Gragert L, Madbouly A, Steiner D, Marsh SG, Gourraud PA, Oudshoorn M, van der Zanden H, Schmidt AH, Pingel J. 16(th) IHIW: global analysis of registry HLA haplotypes from 20 million individuals: report from the IHIW Registry Diversity Group. Int J Immunogenet. 2013;40:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Di Giorgio A, Bravi M, Bonanomi E, Alessio G, Sonzogni A, Zen Y, Colledan M, D’Antiga L. Fulminant hepatic failure of autoimmune aetiology in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Yeoman AD, Westbrook RH, Zen Y, Bernal W, Al-Chalabi T, Wendon JA, O’Grady JG, Heneghan MA. Prognosis of acute severe autoimmune hepatitis (AS-AIH): the role of corticosteroids in modifying outcome. J Hepatol. 2014;61:876-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kathemann S, Bechmann LP, Sowa JP, Manka P, Dechêne A, Gerner P, Lainka E, Hoyer PF, Feldstein AE, Canbay A. Etiology, outcome and prognostic factors of childhood acute liver failure in a German Single Center. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:722-728. [PubMed] |