Published online Dec 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i47.8426

Peer-review started: September 23, 2017

First decision: October 11, 2017

Revised: October 20, 2017

Accepted: November 1, 2017

Article in press: November 1, 2017

Published online: December 21, 2017

Processing time: 88 Days and 10.6 Hours

Hepatic encephalopathy is suspected in non-cirrhotic cases of encephalopathy because the symptoms are accompanied by hyperammonaemia. Some cases have been misdiagnosed as psychiatric diseases and consequently patients hospitalized in psychiatric institutions or geriatric facilities. Therefore, the importance of accurate diagnosis of this disease should be strongly emphasized. A 68-year-old female patient presented to the Emergency Room with confusion, lethargy, nausea and vomiting. Examination disclosed normal vital signs. Neurological examination revealed a minimally responsive woman without apparent focal deficits and normal reflexes. She had no history of hematologic disorders or alcohol abuse. Her brain TC did not demonstrate any intracranial abnormalities and electroencephalography did not reveal any subclinical epileptiform discharges. Her ammonia level was > 400 mg/dL (reference range < 75 mg/dL) while hepatitis viral markers were negative. The patient was started on lactulose, rifaximin and low-protein diet. On the basis of the doppler ultrasound and abdomen computed tomography angiography findings, the decision was made to attempt portal venography which confirmed the presence of a giant portal-systemic venous shunt. Therefore, mechanic obliteration of shunt by interventional radiology was performed. As a consequence, mesenteric venous blood returned to hepatopetally flow into the liver, metabolic detoxification of ammonia increased and hepatic encephalopathy subsided. It is crucial that physicians immediately recognize the presence of non-cirrhotic encephalopathy, in view of the potential therapeutic resolution after accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatments.

Core tip: We present the case of a non-cirrhotic female patient who first presented to the Emergency Room with acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy causing massive relapsing neurological symptoms due to a huge inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the left internal iliac vein which was successfully cured by interventional radiology procedure. Therefore, the importance of accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment of this disease should be strongly emphasized.

- Citation: de Martinis L, Groppelli G, Corti R, Moramarco LP, Quaretti P, De Cata P, Rotondi M, Chiovato L. Disabling portosystemic encephalopathy in a non-cirrhotic patient: Successful endovascular treatment of a giant inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the left internal iliac vein. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(47): 8426-8431

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i47/8426.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i47.8426

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) most commonly occurs in patients with cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease. Non cirrhosis-related HE is, by far, less frequently encountered[1]. The development of HE in the absence of liver disease is mainly dependent upon the presence of spontaneous portal vein thrombosis or portosystemic shunts which ultimately lead to hyperammonaemia[1]. At difference with HE associated with end-stage liver disease, in these latter cases interventional radiology procedures provide a chance of complete remission[1-3]. Abdominal trauma, prior surgery, post-natal viral or hepatotoxic injuries could potentially induce the occurrence of portosystemic shunts without liver disease. There are, however, shunts retaining the onphalomensenteric venous system which have in most cases a congenital origin[1,4-9]. Owing to overlapping neurological symptoms due to hyperammonaemia, at least some patients with HE have been misdiagnosed as harbouring psychiatric diseases (such as dementia, depression and others) with subsequent hospitalization in psychiatric institutions or geriatric facilities[9,10]. The above cited evidences highlight the need for an accurate differential diagnosis between the spectrum of neurologic conditions and the, by far less frequent, non cirrhosis related HE, especially in view of the potential therapeutic resolution of the latter condition[1]. We hereby report the case of a non-cirrhotic patient who first presented with acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy causing massive relapsing neurological symptoms due to a huge inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the left internal iliac vein which was successfully cured by interventional radiology procedure.

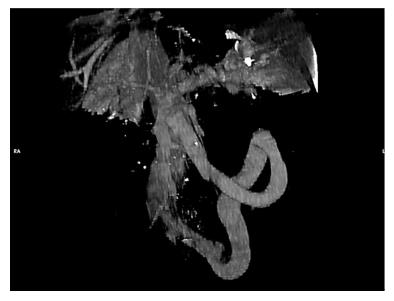

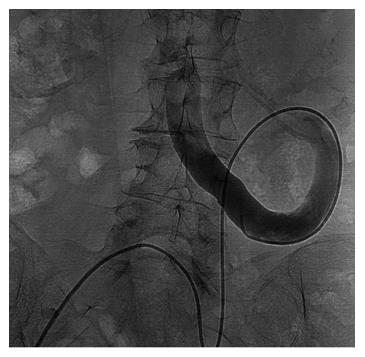

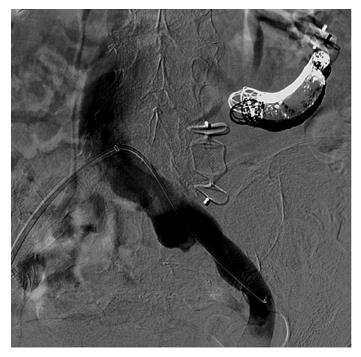

A 68-year-old female patient presented three times to the Emergency Room with confusion, lethargy, dysarthria, nausea and vomiting. Each time the first evaluation disclosed normal vital signs where neurological examination always revealed a minimally responsive woman without apparent focal deficits but with asterixis and increased tendon reflexes. The crisis resolved after conservative therapy. Brain computed tomography (CT) showed chronic cerebral vascular disease, absence of any acute intracranial lesions and electroencephalography did not reveal any subclinical epileptiform sign. Chest X-ray did not reveal any insurgent abnormalities, except for outcome signs of fractures of the IV, V and VI ribs that patients reported two months before because of an accidental fall. Normal levels of hemoglobin, leukocytes, platelets, glucose, electrolytes and creatinine were found. In the last admission serum ammonia level was finally measured and found to be far above the normal value (nv < 75 mg/dL): > 400 mg/dL. Based on these findings, the patient was eventually transferred to our Internal Medicine department and started on lactulose, rifaximin, low-protein diet. The past medical history revealed: normal growth and pubertal development with no history of congenital malformation, left quadrantectomy plus lymphadenectomy followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy with tamoxifen for breast carcinoma in 2003 (at that time patient was declared free of disease and was not taking any anti-cancer therapy); hypertension in treatment with beta-blockers and ace-inhibitors; mechanic aortic valve replacement due to severe aortic stenosis for which was taking oral anticoagulants and pacemaker implantation in 2007; depression and migraine self-treated. She had no history of alcohol abuse, hematologic disorder or liver disease. The biochemical assessment showed: normal thyroid function, euglycemia, normal levels of ACTH and cortisol, normal GH with low IGF-1 for age (37 ng/mL 116-353 ng/mL), INR in range (between 2.5 and 3.5 for mechanic valve), normal renal function and sodium/potassium levels. Slightly elevated transaminases (GOT 59 U/L, nv < 32 U/L; GPT 56 U/L , nv < 33 U/L) and direct/indirect bilirubin (1.3 mg/dL, nv < 1.2 mg/dL; 0.7 mg/dL, nv < 0.3 mg/dL) were also found. Viral Hepatitis markers (HAV/HBV/HCV/HEV) were negative as well as HIV1-2 serology, tumor markers (CEA/CA19.9/CA15.3/CA125/alpha-fetoprotein/NSE/CYFRA21-1) and humoral autoimmunity (ANA/ENA/pANCA/cANCA/AMA/ASMA/LKM1/SLA-LP) markers. There was not a history of hepatotoxic drugs assumption or alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Hemochromatosis and Wilson’s disease were ruled out based upon normal circulating levels of iron, ferritin, transferrin, copper and ceruloplasmin. The persistent presence of variable floating degree of hyperammonaemia, unresponsive to conventional treatment, prompted us to take into account more rare causes sustaining high levels of circulating ammonia in the absence of liver disease. Gastroscopy and colonscopy did not identify any bleeding or macroscopic alteration (in particular absence of gastroesophageal varices) of the gastrointestinal tract and obstinate constipation did not affect our patient. She was not taking any drug potentially producing hyperammonemia and had not performed a high-protein diet. Coproculture was negative and excluded bacterial colonization, urine culture was positive for E. coli and the asymptomatic infection was easily treated. Lastly, plasmatic and urinary amino acids chromatography excluded the rare condition of urea cycle disorders. Abdominal ultrasound revealed normal liver volume and echogenicity without focal lesions and no ascites. EcoColor Doppler ruled out thrombosis of portal vein and its intrahepatic branches with hepatopetal flow. Main portal trunk diameter was within normal values (< 1.5 cm) with enlarged appearance of splenoportal confluence. Brain MRI examination was not performed because of the presence of mechanic aortic valve. Abdomen computed tomography angiography revealed the patency of portal vein trunk with an enlarged superior mesenteric vein and a giant portosystemic shunt. The shunt presented a maximum caliber of 20 mm and showed a large retroperitoneal loop emerging from the spleno-mesenteric confluence with discharge in the left hypogastric vein (Figure 1). No collateral gastroesophageal pathways of portal circulation, normal spleen volume and no ascites were found. Then, hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) measurement of portal vein pressure was performed. From right internal jugular vein the right hepatic vein was catheterized. HVPG of 1 mmHg (free flow 13 mmHg; wedge 14 mmHg) was recorded thrice with repeated occlusion balloon (Occluder, Boston Sc., United States) inflations and deflations. To test the hypothesis of a possible pre-hepatic portal hypertension, causing a misleading low HVPG, a 5 French (Fr) diagnostic catheter was negotiated through the inferior vena cava and the shunt directly in portal vein. Hepatopetal portal flow was opacified and direct portal pressure was 14 mmHg, confirming the HVPG value. Fibroscan examination revealed liver elastance of 10 KPA compatible with a low probability of clinically significant liver cirrhosis. Thus, it was not worth the risk to perform a liver biopsy taking into account that the patient was on anticoagulant therapy. Three days later transfemoral embolization of the shunt was performed. Thus, by right groin access the contralateral shunt outflow in left hypogastric vein was catheterized (Figure 2). A 45 cm long 8 Fr introducer was engaged deeply inside the left hypogastric vein and a 5 Fr catheter (Glidecath, Terumo) was advanced over a 0.035”inch glide guidewire through the loop of the shunt up to the main trunk of portal vein. Then a high flow microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo) was inserted through a side-valve into the 5 Fr catheter. Thereafter multiple coils (Ruby Coils, Penumbra INC, United States), for a total length of 974 cm, were released. Due to apparent instability of the cast of coils, the 8 Fr introducer was advanced over the 5 Fr catheter, the last was eventually removed. More proximally two large nitinol plugs were deployed near the shunt confluence in the internal iliac vein (Figure 3). Mechanical embolization was preferred to sclerosis with chemical agents to avoid the risk of reflux in the portal system with potential catastrophic complications. A control CT at 1 mo confirmed the complete shunt exclusion (Figure 4). As a consequence, mesenteric venous blood restarted to fully hepatopetally flow into the liver. The venous blood containing a high level of ammonium reached once again the liver where metabolic ammonia detoxification increased and encephalopathy subsided. After that, we observed a complete remission of symptoms, normalization of transaminases (GOT 26 U/L, nv < 32 U/L; GPT 22 U/L, nv < 33 U/L), direct/indirect bilirubin (1.1 mg/dL, nv < 1.2 mg/dL; 0.2 mg/dL, nv < 0.3 mg/dL) and ammonia level 35 mg/dL (nv < 75 mg/dL), in the absence of any specific therapy, and stable conditions after a two years follow up.

Hepatic encephalopathy is in most cases a direct consequence of cirrhosis, which generates portal-systemic venous shunts ultimately resulting in by-pass of the liver. This latter aspect accounts for the fact that neurotoxic substances, such as ammonia, are not effectively detoxified by the liver and flow in high concentrations into the systemic circulation affecting the brain[1]. However, even if, by far less frequent, cases of hyperammonemia not associated with cirrhosis were previously described. Indeed, elevated concentrations of circulating ammonia in patients with normal liver function were reported in a wide spectra of conditions which include high protein diet, severe constipation, gastrointestinal bleeding, several drugs, gastric Helicobacter pylori infection and urinary tract infection with high urease-producing bacteria (Pseudomonas, Proteus), haemodialysis and enzyme deficit of urea cycle[1-4,6-9]. In our case, the diagnostic evaluation was started by excluding common causes of cirrhosis such as chronic viral, metabolic or autoimmune hepatitis, alcohol abuse, sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, hepatotoxic drugs assumption. Subsequently, the previously mentioned conditions, potentially causing hyperammonemia in the absence of liver impairment, were ruled out. Finally, the presence of a porto-systemic shunt was established on the basis of clinical setting and CT findings. Indeed Multi-detector Computed Tomography clearly depicted the shunt characteristics and allowed the planning for subsequent diagnostic work up. As a first step, HVPG was measured and direct portal pressure was recorded to definitely exclude portal hypertension. In consideration of the clinical setting, including virus markers negativity, as well as of the endoscopic and imaging findings and the low value of liver impedance and elastography, transjugular biopsy was considered unnecessary according to the most recent expert positions[11]. MRI can provide an accurate tool for studying in a non-invasive way the acute/chronic damage on brain[1]. However, as mentioned before, MRI was not executable in our patient because of the mechanic aortic valve. In (Table 1) are shown the cases of non cirrhosis-related HE reported in the literature as compared to the present case[2,3,12] and the peculiarities of each one. Although in cirrhotic patients, He et al[13,14], reported a case of inferior mesenteric vein-left gonadal vein shunt aggravating HE and a case of large paraesophageal varices causing recurrent HE. In both cases disabling encephalopathy occurred even after relief of severe portal hypertension by means of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and coil embolization was necessary to achieve full clinical recovery[13,14]. Furthermore, there are some aspects of the present case report that need to be stressed and discussed. First of all, the relapsing and massive neurological presentation really impressed the clinicians, especially because the patient did not have previous history of similar episodes and never suffered from a neurological or hepatic disease. Although it is well known that chronic hyperammonaemia causing encephalopathy could be frequently misdiagnosed with psychiatric disorders[10], acute presentations can be even more difficult to be rapidly identified, hence we believe that measurement of serum ammonia level should be always considered at the first clinical assessment in Emergency Unit. Secondly, the first clinical presentation occurred not only in an acute expression but also very late at 68 year-old age. This does not represent a common finding although it was reported in some cases[12,15-18]. The causal mechanism involves spontaneous formation of a porto-systemic shunt, in this case an inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the left internal iliac vein, that might be provoked by several trigger factors[1]. Our patient reported multiple rib fractures, due to an accidental fall, just two months before the explosion of neurological symptoms and trauma is one of the several causes reported to be a possible source of spontaneous vascular shunts in human body[1]. However shunt was too big in size to be justified by the recent trauma, supporting the hypothesis of a preexisting vessel progressively increased in size over the years, which acquired major vascular relevance. On the contrary, it seemed more likely that the trauma was the consequence of the hyperammoniemia-related impairment of cerebral function. Relationship between the size of portal and shunt diameters and time of symptoms occurrence have already been reported[19]. Lastly, the Fibroscan showed a low degree of fibrosis for a virus negative patient, not proportional to the degree of hyperammonaemia[20]. These data, together with the mild hypertransaminasemia, suggest a minor liver impairment. Indeed, the hyperammonaemia correlates with liver damage severity in cirrhotic patients and represents a clue for the presence of portosystemic collateral veins[21]. Moreover, mild hepatic fibrosis, fatty degeneration, infiltration of lymphocytes or intrahepatic vascular abnormalities have all been observed as consequences of portosystemic shunts[1]. The most likely explanation for these minimal liver involvement would be that when blood flow to the liver reduces, and it leads to lack of nutrition and fatty degeneration of hepatic cells, hepatic disfunction, cellular death and then liver atrophy/fibrosis occurs[1]. However, there is a chance of complete biochemical, histological and clinical remission after interventional radiology procedures achieving shunt exclusion[3]. For this reason, it is crucial that physicians initially recognize the presence of hyperammonemic encephalopaty and then, consider the rare case in which the condition is not related to cirrhosis, and can therefore be fully healed. Accurate diagnosis and subsequent appropriate treatments are able to fully revert the symptoms in most patients. However, future studies aimed at evaluating the long-term prognosis after therapy are necessary.

| Ref. | Patient | Presentation | Type of shunt | Treatment |

| Otake et al[2], 2001 | 37 yr, Female, no relevant past medical history | Disturbed consciousness | Inferior mesenteric-caval shunt (left internal iliac vein) | Percutaneous transcatheter embolization (Coils) |

| Rogal et al[3], 2014 | 58 yr, Male, gastric by-pass surgery | 4 mo of confusion and violent behavior | Spontaneous splenorenal shunt (18 mm) | Percutaneous closure (Amplatzer plug) |

| Ali et al[12], 2010 | 57 yr, Female, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus | 2 wk of confusion, new onset melena | Superior mesenteric-caval shunt (left internal iliac vein) (10-20 mm) | Surgical closure |

| Present case | 68 yr, Female, breast cancer, rib fractures | Relapsing confusion, lethargy, dysarthria | Inferior mesenteric-caval shunt (left internal iliac vein) (20 mm) | Percutaneous transcatheter embolization (Amplatzer plug and coils) |

A 68-year-old female patient presented three times to the Emergency Room with confusion, lethargy, dysarthria, nausea and vomiting.

Disabling portosystemic encephalopathy due to a giant inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the left internal iliac vein.

Elevated concentrations of circulating ammonia in patients with normal liver function were reported in a wide spectra of conditions which include high protein diet, severe constipation, gastrointestinal bleeding, several drugs, gastric Helicobacter pylori infection and urinary tract infection with high urease-producing bacteria (Pseudomonas, Proteus), haemodialysis and enzyme deficit of urea cycle.

Serum ammonia level was found far above the normal value > 400 mg/dL (nv < 75 mg/dL). Euthyroidism, euglycemia, normal levels of ACTH and cortisol, normal GH with low IGF-1 for age INR in range, normal renal function and sodium/potassium levels were observed. Slightly elevated transaminases and direct/indirect bilirubin were detected. Viral Hepatitis markers were negative as well as HIV1-2 serology, tumor markers and humoral autoimmunity markers.

Abdomen computed tomography angiography revealed the patency of portal vein trunk with an enlarged superior mesenteric vein and a giant portosystemic shunt. The shunt presented a maximum caliber of 20 mm and showed a large retroperitoneal loop emerging from the spleno-mesenteric confluence with discharge in the left hypogastric vein.

Giant inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the left internal iliac vein.

Percutaneous transcatheter embolization using Amplatzer plug and coils.

Mechanical embolization of an inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the left internal iliac vein was described in a similar case by Otake et al[2], Intern Med 2001.

Mechanical embolization was preferred to sclerosis with chemical agents to avoid the risk of reflux in the portal system with potential catastrophic complications. A control CT confirmed the complete shunt exclusion. As a consequence, mesenteric venous blood restarted to fully hepatopetally flow into the liver, metabolic detoxification of ammonia increased and encephalopathy subsided.

It is crucial that physicians initially recognize the presence of hyperammonemic encephalopaty and then, even if rare, consider those case not related to cirrhosis that can therefore be fully healed. Accurate diagnosis and subsequent appropriate treatments are able to fully revert the symptoms in most patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cao WK, Qi X, Tarantino G, Watanabe T S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Watanabe A. Portal-systemic encephalopathy in non-cirrhotic patients: classification of clinical types, diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:969-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Otake M, Kobayashi Y, Hashimoto D, Igarashi T, Takahashi M, Kumaoka H, Takagi M, Kawamura K, Koide S, Sasada Y. An inferior mesenteric-caval shunt via the internal iliac vein with portosystemic encephalopathy. Intern Med. 2001;40:887-890. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Rogal SS, Hu A, Bandi R, Shaikh O. Novel therapy for non-cirrhotic hyperammonemia due to a spontaneous splenorenal shunt. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8288-8291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cacciapaglia F, Vadacca M, Coppolino G, Buzzulini F, Rigon A, Zennaro D, Zardi E, Afeltra A. Spontaneous splenorenal shunt in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome: the first case reported. Lupus. 2007;16:56-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Achiron R, Kivilevitch Z. Fetal umbilical-portal-systemic venous shunt: in-utero classification and clinical significance. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:739-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zaret BS, Beckner RR, Marini AM, Wagle W, Passarelli C. Sodium valproate-induced hyperammonemia without clinical hepatic dysfunction. Neurology. 1982;32:206-208. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ohtani Y, Ohyanagi K, Yamamoto S, Matsuda I. Secondary carnitine deficiency in hyperammonemic attacks of ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. J Pediatr. 1988;112:409-414. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ito S, Miyaji H, Azuma T, Li Y, Ito Y, Kato T, Kohli Y, Kuriyama M. Hyperammonaemia and Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1995;346:124-125. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Canzanello VJ, Rasmussen RT, McGoldrick MD. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy during hemodialysis. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:190-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Takatama M. Hepatic encephalopathy in aged patients and its differential diagnosis from dementia. Med Trib 21 September. 1989;. |

| 11. | Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of Liver Imaging and Biopsy in Clinical Practice. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:756-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ali S, Stolpen AH, Schmidt WN. Portosystemic encephalopathy due to mesoiliac shunt in a patient without cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:381-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | He C, Qi X, Guo W, Yin Z, Han G. Education and Imaging. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: inferior mesenteric vein-left gonadal vein shunt aggravating hepatic encephalopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | He C, Qi X, Han G. Large paraesophageal varices causing recurrent hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Med Sci. 2014;348:512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Matthews TJ, Trochsler MI, Bridgewater FH, Maddern GJ. Systematic review of congenital and acquired portal-systemic shunts in otherwise normal livers. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1509-1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ohnishi K, Hatano H, Nakayama T, Kohno K, Okuda K. An unusual portal-systemic shunt, most likely through a patent ductus venosus. A case report. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:962-965. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yamashita S, Nakata K, Muro T, Furukawa R, Kusumoto Y, Munehisa T, Miyake S, Nagataki S, Ishii N, Koji T. [A case of hepatic encephalopathy due to diffuse intrahepatic porto-systemic shunts]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 1982;71:844-850. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Matsuura B, Akamatsu K, Kitai K, Kimura H, Ohta Y. [A case report of portal-systemic encephalopathy with normal portal vein pressure and non-cirrhosis of the liver]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1987;84:1684-1689. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Uchino T, Matsuda I, Endo F. The long-term prognosis of congenital portosystemic venous shunt. J Pediatr. 1999;135:254-256. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Roulot D, Czernichow S, Le Clésiau H, Costes JL, Vergnaud AC, Beaugrand M. Liver stiffness values in apparently healthy subjects: influence of gender and metabolic syndrome. J Hepatol. 2008;48:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tarantino G, Citro V, Esposito P, Giaquinto S, de Leone A, Milan G, Tripodi FS, Cirillo M, Lobello R. Blood ammonia levels in liver cirrhosis: a clue for the presence of portosystemic collateral veins. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |