Published online Aug 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5817

Peer-review started: February 12, 2017

First decision: March 16, 2017

Revised: April 3, 2017

Accepted: May 4, 2017

Article in press: May 4, 2017

Published online: August 21, 2017

Processing time: 190 Days and 6 Hours

Plexiform fibromyxoma is a very rare mesenchymal tumor of the stomach, found almost exclusively in the antrum/pylorus region. The most common presenting symptoms are anemia, hematemesis, nausea and unintentional weight loss, without sex or age predilection. We describe here two cases of plexiform fibromyxoma, involving a 16-year-old female and a 34-year-old male. Both patients underwent complete resection (R0) by distal gastrectomy and retrocolic gastrojejunostomy (according to Billroth 2); for both, the postoperative course was uneventful. Histology showed multiple intramural and subserosal nodules with characteristic plexiform growth, featuring bland spindle cells situated in an abundant myxoid stroma with low mitotic activity. Immunohistochemistry showed α-smooth muscle actin-positive spindle cells, focal positivity for CD10, and negative staining for KIT, DOG1, CD34, S100, β-catenin, STAT-6 and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. One of the cases showed focal positivity for h-caldesmon and desmin. Upon follow-up, no sign of disease was found. In the differential diagnosis of plexiform fibromyxoma, it is important to exclude the more common gastrointestinal stromal tumors as they have greater potential for aggressive behavior. Other lesions, like neuronal and vascular tumors, inflammatory fibroid polyps, abdominal desmoid-type fibromatosis, solitary fibrous tumors and smooth muscle tumors, must also be excluded.

Core tip: Plexiform fibromyxoma is a very rare benign mesenchymal tumor of the stomach. Here, we describe two cases of plexiform fibromyxoma, resolved with complete resection. The macroscopic, microscopic, immunohistochemical and molecular findings are reviewed. In the differential diagnosis of plexiform fibromyxoma, it is important to exclude the more common gastrointestinal stromal tumors as they have potentially more aggressive behavior.

- Citation: Szurian K, Till H, Amerstorfer E, Hinteregger N, Mischinger HJ, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Brcic I. Rarity among benign gastric tumors: Plexiform fibromyxoma - Report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(31): 5817-5822

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i31/5817.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5817

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common gastric mesenchymal tumors[1]. Immunohistologically, they show positive staining for KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase [KIT, cluster of differentiation (CD)117] and DOG1 (discovered on GIST-1), and the vast majority of cases harbor mutations in the KIT or PDGFRα (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha) genes. Plexiform fibromyxoma (PFM), also known as the plexiform angiomyxoid myofibroblastic tumor (PAMT), is a very rare benign mesenchymal gastric tumor, arising almost exclusively in the antrum/pylorus region. It was first described by Takahashi et al[2] in 2007. The cases reported to date have indicated no sex predilection and with a wide age range[3-5]. Clinical symptoms include anemia and hematemesis, which are consequent to tumor ulceration, nausea and weight loss.

Herein, we describe the specific histopathological features of two cases of PFM in regard to the current literature and discuss misleading differential diagnoses.

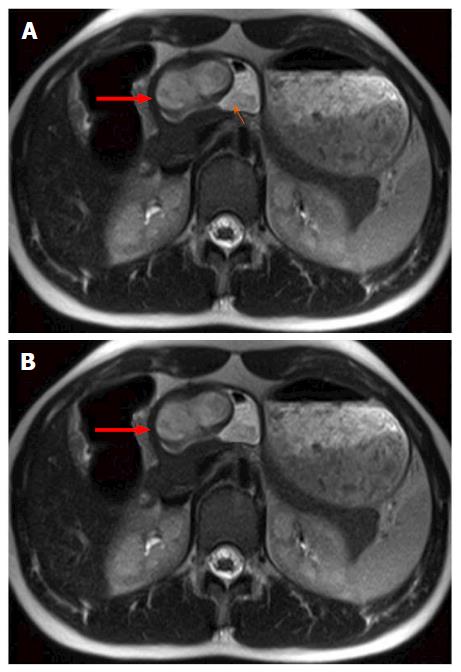

A 16-year-old Caucasian female patient presented with refractory anemia, first detected following a skiing accident. She was treated in an outpatient setting, with iron, vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation. In history taking, the patient reported recurrent nausea; otherwise, the medical history and physical examination were unremarkable. Laboratory findings showed no significantly altered values, except for a moderate, normochromic, normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL; normal range: 12.1-15.1 g/dL). During work-up, ultrasound examination detected a hypoechoic lesion in the gastric wall. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a heterogeneously enhancing, lobulated, exophytic mass, situated intramural within the submucosa of the anterior wall of the gastric antrum (Figure 1). Positron emission tomography-computed tomography further revealed a hypermetabolic lesion in the dorsal part of the mass. Endoscopy confirmed a subepithelial lesion with partially ulcerated mucosa in the gastric antrum, necessitating a distal gastrectomy for complete resection.

A 34-year-old obese male patient with unremarkable medical history presented with complaint of discomfort in the epigastric region accompanied by flatulence. Laboratory findings were within normal limits, except for slightly higher creatine kinase (227 U/L; normal range: 52-336 U/L) and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (377 U/L; normal range: 105-333 U/L). Gastroscopy revealed a pyloric submucosal lesion, suspicious of GIST. Biopsy showed foveolar hyperplasia of antral mucosa, with no submucosa.

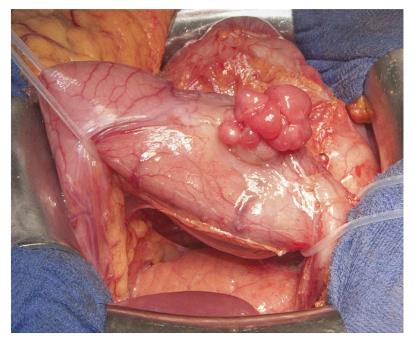

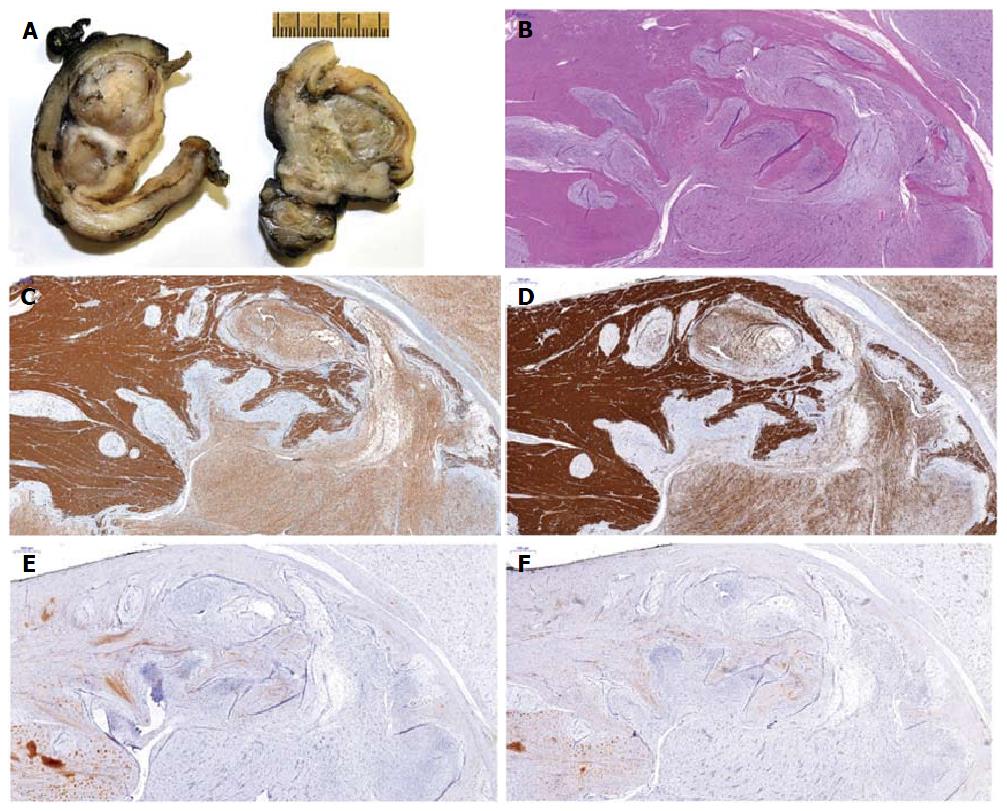

Both patients underwent distal gastrectomy for complete resection (R0) and retrocolic gastrojejunostomy (according to Billroth 2) (Figure 2). Gross examination of the specimens from both cases showed well-circumscribed lobulated tumors, with the largest diameter measuring 6.5 cm in case 1 and 1.6 cm in case 2. Examination of the cut surface showed both tumors to be well demarcated and solid, with mucoid consistency. A multinodular growth pattern was apparent, mostly involving the submucosa, muscularis propria and subserosal adipose tissue (Figure 3A). Overlying mucosa was focally ulcerated.

For both cases, histological analysis showed multiple intramural and subserosal nodules of characteristic plexiform growth, with cytological bland spindle cells situated in an abundant myxoid stroma having prominent capillary network and scattered inflammatory and mast cells (Figure 3B). Mitotic activity was low (up to 3/50 high power fields, HPF). Mucosal involvement with ulceration was observed; however, there was no necrosis and all resection margins were free of tumor.

Immunohistochemically, both cases showed positive reaction for alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Figure 3C) and focal positivity for CD10. Furthermore, the case 1 tumor cells showed focal positivity for h-caldesmon (Figure 3D) and desmin, while case 2 tumor cells showed negativity for h-caldesmon and desmin. In both cases, the tumor cells were negative for KIT (Figure 3E), DOG1 (Figure 3F), hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen CD34 (CD34), S100, β-catenin, signal transducer and activator of transcription 6, interleukin-4 induced (STAT-6) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Neither tumor was succinate dehydrogenase complex iron sulfur subunit B (SDHB)-deficient. Mutational status analysis was performed for case 1, and no mutations were found in KIT (exons 9, 11, 13, 17, 18 or 20) or PDGFRA (exons 12, 14 or 18) by direct sequencing using paraffin-embedded tissue samples (Custom Ion Torrent AmpliSeq Panel; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States).

In both cases, these findings led to the final diagnosis of PFM. Postoperatively, case 1 developed pulmonary embolism, which was treated by administration of anticoagulants. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 9. The postoperative course of case 2 was uneventful and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 11. At the last follow-up (6 and 16 mo postoperative respectively), neither patient showed evidence of residual or recurrent disease, nor complained of symptoms of dumping syndrome, afferent loop syndrome or gastroesophageal reflux.

PFMs are very rare gastric mesenchymal tumors. To date, various names have been proposed to describe this benign spindle cell tumor, including fibromyxoma, plexiform angiomyxoid tumor, and PAMT[2,6]. In 2009, Miettinen et al[4] described 12 cases of benign gastric antral fibromyxoid tumors, designating them as PFM. In 2010, this term was accepted and these tumors became recognized as a distinct entity, according to World Health Organization’s classification of tumors of the digestive system[7].

Cases of PMFs reported show no trend in age (range: 7-75 years) but indicate an almost exclusive location in the gastric antrum and pyloric region, with up to 20% of cases spreading to the duodenal bulb[4]. Like in our patients, extension to the exterior surface of the stomach and proximal duodenum has been described. The size can range from 1.5 to 15 cm[5]. Two-thirds of the tumors are ulcerated, putting these patients at risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and secondary anemia. Other clinical features include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and unintentional weight loss. These symptoms can also be found in patients with GIST, a mesenchymal tumor that is common in the stomach and more aggressive, and which must always be considered as a differential diagnosis for PMF. PMFs are asymptomatic, and thus primarily discovered incidentally. Our first patient presented with refractory anemia, and the tumor was detected by ultrasound examination. The second patient complained of discomfort in the epigastric region.

On gross examination, these tumors are not encapsulated and present as (multi)nodular lesions, variably involving the intramucosal to subserosal and serosal parts of the stomach. In fact, tumor projection toward the serosal surface is commonly encountered in this entity. Histological features are quite typical and show a plexiform growth pattern with multiple nodules composed of abundant paucicellular to moderately cellular myxoid or fibromyxoid stroma, and having prominent small vessels and bland-looking monomorphic tumor cells within the gastric wall and subserosa. In some cases, more collagenous stroma is observed-feature most commonly seen in the extramural extension. The tumor cells range from oval to spindle in shape, and show no atypia. Mitoses are rare (up to 7/50 HPF)[4,5,8]. Ulceration and invasion of the mucosa can be found. Miettinen et al[4] reported vascular invasion in 4 patients, suggesting possible intravascular tumor spread within the gastric wall and subserosa. In our cases, multiple tumor nodules were displayed in all gastric layers. Serosa was intact and no intravascular component was noted. Tumor cells were bland-looking, embedded in mildly cellular stroma that was more collagenous in the extramural parts of the tumors. Up to 3 mitotic figures were found on 50 HPF. In addition, an extensive capillary network and scattered inflammatory and mast cells were found within the stroma.

Immunohistochemically, tumor cells usually show focal to diffuse positive reaction with vimentin, α-SMA and CD10, and sometimes with desmin and/or h-caldesmon or calponin[2,4-6,9,10]. This immunoprofile indicates that these tumors contain cells with myofibroblastic and fibroblastic and/or smooth muscle cell characteristics, all of which were observed as present in one of our cases. However, the predominant cell type is myofibroblastic in the majority of the reported cases. Quero et al[6] compiled the clinicopathologic characteristics of all cases published up to March 2016. We present in Table 1 the collective immunohistochemical findings for desmin and h-caldesmon/calponin, as well as the findings for the two newest cases presented herein. The expression of myogenic markers in some of the tumors suggests that a subset of these tumors contain not only tumor cells with myofibroblastic-fibroblastic phenotype but also tumor cells with true smooth muscle differentiation[9]. For those tumors, some authors prefer to use the term “PAMT”; this would suggest that PMFs, plexiform myofibroblastic tumors and PAMTs are slightly different entities in the spectrum of benign plexiform myxoid (myo)fibroblastic lesions of the stomach.

| Desmin | h-Caldesmon/Calponin | |

| (-) | 23 (37.7) | 15 (24.6) |

| f (+) | 14 (22.9) | 10 (16.4) |

| (+) | 4 (6.4) | 4 (6.6) |

| NA | 20 (33.0) | 32 (52.4) |

| Total | 61 (100.0) | 61 (100.0) |

In all of these tumor types, negativity for immunohistochemical staining with KIT, DOG1, CD34, epithelial membrane antigen, beta-catenin and S100 has been reported[2,4-6,9,10]. A negative finding for KIT and DOG1 excludes GIST, especially for the plexiform myxoid type, while a negative finding for S100 excludes neuronal tumors (i.e., schwannoma and neurofibroma). Vascular lesions should show positivity for CD34, CD31 and ETS-related gene, which is a distinguishing feature from PMF. Other differential diagnoses include fibroblastic tumors [i.e., inflammatory fibroid polyp, abdominal desmoid-type fibromatosis (nuclear β-catenin staining) and solitary fibrous tumor (CD34 and nuclear STAT6 expression)] and smooth muscle tumors (i.e., leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma). Quero et al[6] reported that only four of the published cases showed positive expression for h-caldesmon or calponin, albeit diffuse.

The tumor from one of our patients showed focal positivity for h-caldesmon. These cases can be diagnostically challenging and difficult to differentiate from myxoid leiomyomas. They more commonly arise in the gastric cardia or fundus, have plexiform architecture and contain, at least, focal fascicles of tumor cells with typical eosinophil cytoplasm (i.e., morphological features compatible with smooth muscle differentiation)[1,11]. The discontinuous plexiform multinodular pattern is more of a characteristic of PFM. In female patients, metastatic low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) should be ruled out by testing for status of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression, positivity for both of which is characteristic of low-grade ESS. Furthermore, in low-grade ESS, the following translocations have been described: JAZF1-SUZ12 and MEAF6-PHF1. On the other hand, high-grade ESSs are ER- and PR-negative, and can have YWHAE-FAM22 translocation.

Mutational analysis has been performed in some of the cases published, but none reported detection of KIT or PDGFRα mutations[4-6]. The same results were found in one of our cases (the other was not tested). In contrast, GIST typically bear KIT or PDGFRα activating mutations; however, approximately 10% of GISTs in adults and more than 90% in children lack these mutations, and are then classified as wild-type GISTs[12], being either succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-deficient or non-SDH-deficient[13,14]. The SDH-deficient type encompasses cases of Carney triad and Carney Stratakis syndrome, as well as some sporadic cases. These tumors are usually found in young women, typically occur in the antrum and show a characteristic multifocal/multinodular and plexiform growth pattern. However, the tumors are more cellular, composed of epithelioid cells that are immunohistochemically positive for KIT and DOG1. Further, PDGFRα mutations have also been described in inflammatory fibroid polyps. Recently, Spans et al[15] described a recurrent translocation-t(11;12)(q11;q13), involving the long non-coding gene metastases-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 and the gene glioma-associated oncogene homologue 1 (GLI1)-in a subgroup of PMTs.

Surgery with negative resection margins is the treatment of choice. This tumor is considered to be a benign lesion, and to date no cases of recurrence or distant metastases after complete surgical resection have been reported[4]. Upon follow-up of our 2 patients, no sign of disease was found.

In summary, different terms have been used to describe the benign gastric tumor with prominent plexiform and myxoid pattern. Current histomorphological and immunohistochemical findings suggest that PMFs, plexiform myofibroblastic tumors and PAMTs are slightly different entities in the spectrum of benign plexiform myxoid (myo)fibroblastic (spindle cell) lesions of the stomach. Most importantly, it is crucial to differentiate these tumors from the more common GISTs, as the latter have greater potential for aggressive behavior. GISTs and other gastric myxoid tumors are distinguishable upon investigation of a wide panel of immunohistochemical markers and mutational status analysis of both the KIT and PDGFRα genes.

Two cases of plexiform fibromyxoma presented with discrete symptoms. The first was a 16-year-old female, with incidentally found refractory anemia, and the second was a 34-year-old male, who presented with discomfort in the epigastric region accompanied by flatulence.

Physical examination of both patients was unremarkable. On gastroscopy, however, submucosal tumor was observed, situated in the antral region.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), inflammatory fibroid polyp, abdominal desmoid-type fibromatosis, solitary fibrous tumor, leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma.

In the first case, laboratory findings showed moderate, normochromic, normocytic anemia (hemoglobin of 9.5 g/L). The second case showed a slight increase in creatine kinase (227 U/L) and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (377 U/L).

In the first case, ultrasound examination of the abdomen displayed a hypoechoic lesion in the gastric wall, magnetic resonance imaging revealed a heterogeneously enhancing, lobulated, exophytic mass, situated intramural within the submucosa of the anterior wall of the gastric antrum, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography showed a hypermetabolic lesion. In the second case, only gastroscopy was performed, and it revealed a 3-cm large submucosal lesion.

For both cases, histology showed multiple intramural and subserosal nodules with characteristic plexiform growth featuring bland spindle cells situated in an abundant myxoid stroma with a prominent capillary network.

Both patients underwent distal gastrectomy and retrocolic gastrojejunostomy (according to Billroth 2).

Reports of cases of plexiform fibromyxoma in the literature are rare. Macroscopic, microscopic, immunohistochemical and molecular findings are crucial for exclusion of the more common gastrointestinal stromal tumors, which have potentially more aggressive behavior.

Plexiform fibromyxoma, also known as a plexiform angiomyxoid myofibroblastic tumor, is a very rare mesenchymal tumor of the stomach, found almost exclusively in the antrum/pylorus region.

This report presents the characteristic findings of plexiform fibromyxoma. Gastric GIST should be excluded in the differential diagnosis.

The authors have described two cases of very rare gastric plexiform fibromyxoma that were successfully resected. The article highlights the macroscopic, histologic, immunohistochemical and molecular findings typical of theses tumors and provides insights into the correct diagnosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Austria

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lee JI, Park WS, Tovey FI S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Lee HH, Hur H, Jung H, Jeon HM, Park CH, Song KY. Analysis of 151 consecutive gastric submucosal tumors according to tumor location. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:72-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Takahashi Y, Shimizu S, Ishida T, Aita K, Toida S, Fukusato T, Mori S. Plexiform angiomyxoid myofibroblastic tumor of the stomach. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:724-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang LM, Chetty R. Selected unusual tumors of the stomach: a review. Int J Surg Pathol. 2012;20:5-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Miettinen M, Makhlouf HR, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Plexiform fibromyxoma: a distinctive benign gastric antral neoplasm not to be confused with a myxoid GIST. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1624-1632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Takahashi Y, Suzuki M, Fukusato T. Plexiform angiomyxoid myofibroblastic tumor of the stomach. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2835-2840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Quero G, Musarra T, Carrato A, Fici M, Martini M, Dei Tos AP, Alfieri S, Ricci R. Unusual focal keratin expression in plexiform angiomyxoid myofibroblastic tumor: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miettinen M, Fletcher CD, Kindblom LG, Tsui WM. Mesenchymal tumors of the stomach. WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2010; 74-79. |

| 8. | Kane JR, Lewis N, Lin R, Villa C, Larson A, Wayne JD, Yeldandi AV, Laskin WB. Plexiform fibromyxoma with cotyledon-like serosal growth: A case report of a rare gastric tumor and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2189-2194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li P, Yang S, Wang C, Li Y, Geng M. Presence of smooth muscle cell differentiation in plexiform angiomyxoid myofibroblastic tumor of the stomach: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:823-827. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Duckworth LV, Gonzalez RS, Martelli M, Liu C, Coffin CM, Reith JD. Plexiform fibromyxoma: report of two pediatric cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2014;17:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Miettinen MM, Quade B. Leiomyoma of deep soft tissue. WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2013; 110-111. |

| 12. | Joensuu H, Hohenberger P, Corless CL. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet. 2013;382:973-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wada R, Arai H, Kure S, Peng WX, Naito Z. “Wild type” GIST: Clinicopathological features and clinical practice. Pathol Int. 2016;66:431-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Janeway KA, Kim SY, Lodish M, Nosé V, Rustin P, Gaal J, Dahia PL, Liegl B, Ball ER, Raygada M. Defects in succinate dehydrogenase in gastrointestinal stromal tumors lacking KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:314-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 462] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Spans L, Fletcher CD, Antonescu CR, Rouquette A, Coindre JM, Sciot R, Debiec-Rychter M. Recurrent MALAT1-GLI1 oncogenic fusion and GLI1 up-regulation define a subset of plexiform fibromyxoma. J Pathol. 2016;239:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |