Published online Aug 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5798

Peer-review started: February 9, 2017

First decision: May 12, 2017

Revised: June 18, 2017

Accepted: July 12, 2017

Article in press: July 12, 2017

Published online: August 21, 2017

Processing time: 192 Days and 13.2 Hours

To assess the efficacy of a modified approach with transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) using simple customized instruments in male patients with low rectal cancer.

A total of 115 male patients with low rectal cancer from December 2006 to August 2015 were retrospectively studied. All patients had a bulky tumor (tumor diameter ≥ 40 mm). Forty-one patients (group A) underwent a classical approach of transabdominal total mesorectal excision (TME) and transanal intersphincteric resection (ISR), and the other 74 patients (group B) underwent a modified approach with transabdominal TME, transanal ISR, and taTME. Some simple instruments including modified retractors and an anal dilator with a papilionaceous fixture were used to perform taTME. The operative time, quality of mesorectal excision, circumferential resection margin, local recurrence, and postoperative survival were evaluated.

All 115 patients had successful sphincter preservation. The operative time in group B (240 min, range: 160-330 min) was significantly shorter than that in group A (280 min, range: 200-360 min; P = 0.000). Compared with group A, more complete distal mesorectum and total mesorectum were achieved in group B (100% vs 75.6%, P = 0.000; 90.5% vs 70.7%, P = 0.008, respectively). After 46.1 ± 25.6 mo follow-up, group B had a lower local recurrence rate and higher disease-free survival rate compared with group A, but these differences were not statistically significant (5.4% vs 14.6%, P = 0.093; 79.5% vs 65.1%, P = 0.130).

Retrograde taTME with simple customized instruments can achieve high-quality TME, and it might be an effective and economical alternative for male patients with bulky tumors.

Core tip: Distal mesorectal excision is difficult in male patients with low rectal cancers, especially with a bulky tumor. We explored the application of simple instruments including modified retractors and an anal dilator with a papilionaceous fixture to perform transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) in male patients with low rectal cancer. Our results showed that the modified approach with taTME achieved a shorter operative time and better quality of mesorectal excision as compared with the classical approach. This procedure may be an effective and economical alternative for taTME when a giant tumor is encountered in patients with low rectal cancer.

- Citation: Xu C, Song HY, Han SL, Ni SC, Zhang HX, Xing CG. Simple instruments facilitating achievement of transanal total mesorectal excision in male patients. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(31): 5798-5808

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i31/5798.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5798

Rectal cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors that lead to high rates of morbidity and considerable mortality. High-quality surgery is of great importance in curing patients with rectal cancer. Total mesorectal excision (TME), which considers the rectum and mesorectum as one lymphovascular structure and requires its excision within an intact fascia propria[1], has been shown to significantly reduce the rate of local recurrence and increase the survival rate. Therefore, TME is generally accepted as the gold standard for surgical treatment of rectal cancer[2]. However, during the surgical procedure of TME, distal mesorectal excision becomes difficult when the tumor is low and near to the pelvic floor. Williams[3] described the area of the distal rectum that lies within the pelvic floor musculature as “no man’s land” in rectal cancer surgery. The so-called “no man’s land” cannot usually be reached from the abdomen and has been relatively inviolate as far as surgical exploration is concerned. It is particularly difficult to dissect the end of the rectum in some patients with low rectal cancers, such as those with a narrow pelvis and large tumor volume. These conditions may affect the surgical quality and lead to incomplete mesorectal excision and higher local recurrence rates, thus reducing the survival rate[4-6].

Recently, many studies have suggested that a transanal approach may resolve these issues[7,8] by greatly facilitating distal rectal dissection and providing high-quality TME specimens. Most of these studies used a specialized platform, such as a transanal endoscopic operation platform. However, few institutions around the world could perform this surgery. To date, most colorectal surgeons do not have access to the equipment needed for transanal endoscopic operation nor have they had formal training with this device. Moreover, application of transanal endoscopic operation has remained limited due to high costs and the complexity for surgeons.

During the past 10 years, we applied simple customized instruments to perform retrograde transanal TME for male patients with low rectal cancers. With the help of these simple instruments, we have been able to acquire clearer surgical exposure and easily cross the “no man’s land” under direct observation. Here, we introduce this procedure employing simple instruments and present the operative results from our study.

A total of 3497 consecutive patients underwent radical resection for rectal cancer (tumors located within 12 cm of the anal verge) at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (China) between December 2006 and August 2015. Of these, 115 patients were enrolled in this study.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) tumor margin located ≤ 5 cm from the anal verge; (2) palpable resectable primary tumor detectable by digital examination, and no tumor invasion in the external sphincter, levator ani, and puborectalis muscles by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (3) no distant metastasis found before operation; (4) refusal to undergo abdominoperineal resection of the rectal carcinoma and strong desire for sphincter preservation; and (5) huge tumor volume (tumor diameter ≥ 40 mm).

Since 2011, we have recommended temporal stoma to most patients to improve their quality of life in the early period after operation. All of the procedures were performed by three senior colorectal surgeons.

The preoperative clinical stage of rectal cancer was assessed by abdominal computed tomography (CT) and pelvic MRI with 3.0-T system. Patients with stage cTNM II-III were recommended to receive preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy according to Clinical Guideline of Colorectal Cancer in China since 2010, but only 19 patients fulfilled the regimens, which was performed over a 5-wk period. A dose of 45-50 Gy in 25 fractions was administered along with capecitabine (825 mg/m2 per day) to enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy. Surgery was performed in the 6th to 8th weeks after neoradiotherapy.

Step 1: Transabdominal TME. The dissection was started by high ligation of the inferior mesenteric vessels, followed by mobilization of the sigmoid colon, descending colon and splenic flexure of colon. The dissection was performed following the principles of TME working in “the holy plane”, which ensured excision of the whole rectum and mesorectum as one distinct lymphovascular entity.

Step 2: Transanal ISR. The lower margin of the tumor was closed with submucosal purse-string sutures under direct observation, followed by retrograde irrigation of the anal canal with povidone-iodine solution. The rectum and anal canal were circumferentially dissected 2 cm below the tumor. The potential space between the internal and external sphincter was entered and dissected to the superior border of the anorectal ring.

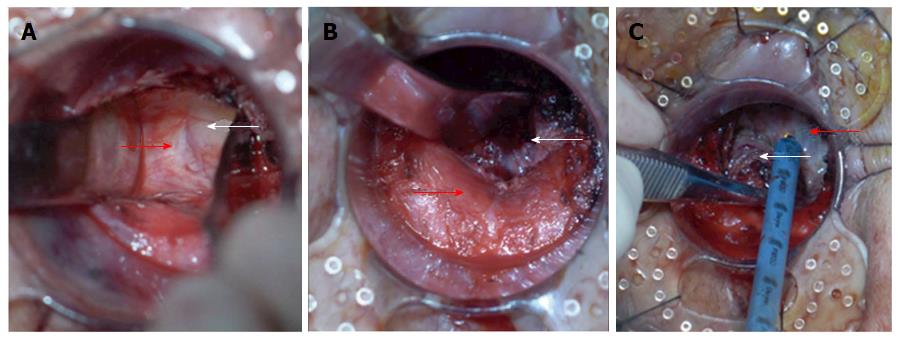

Step 3: Retrograde transanal TME. For preparation of special instruments, two flexible retractors of 25 cm in length were modified from the thyroid retractor and could be adapted to the curvature of the pelvis manually. We also used an anal dilator with a papilionaceous fixture from a stapler device for hemorrhoids (Figure 1).

For retrograde dissection, a circular anal dilator with a diameter of 34 mm was introduced with an obturator device, which replaced the Lone Star Retractor for holding the anal canal open. The dilator was then sutured to the anal margin with four cardinal stitches. After removing the obturator, dissection of the distal mesorectum was pursued by alternating bilateral, posterior and anterior dissection (Figure 2). (1) Bilateral mobilization of the distal rectum (Figure 2A): Dissection was started along the natural boundary between the surface of the levator ani muscle and mesorectum toward the pelvic cavity assisted by two specially designed retractors. After the whole internal sphincter was dissected from the external sphincter, the space between the levator ani muscle and the mesorectum could be detected. The two retractors were inserted into this space and expanded it. The distance of bilateral mobilization toward the pelvic cavity could reach 10 cm according to the length of the retractors; (2) Posterior mobilization of the distal rectum (Figure 2B): The hiatal ligament was cut off after sharp dissection along the natural boundary between the surface of the levator ani muscle and mesorectum with an electrocautery or ultracision harmonic scalpel; and (3) Anterior mobilization of the distal rectum (Figure 2C): The rectourethral muscle was cut off, and the Denonvilliers fascia was sharply dissected between the anterior and posterior lobes. On both sides of the rear of the prostate, the components of the pelvic autonomic nervous plexus (Walsh bundle) were identified and protected. The dissection approached the superior border of the prostate anteriorly and coccygeal posteriorly. Histological evaluation of the invasion of tumor cells was performed on the dissected plane (the external sphincter and/or the levator ani) by microscopic examination of a frozen-section specimen. If any tumor cells were found, the procedure was suspended immediately and converted to abdominoperineal resection.

The tumor specimen was removed when the transanal operation met the gauzes previously placed at the pelvis transabdominally.

Step 4: Abdominal closure. The surgical field was rinsed, and the sigmoid stump was pulled down without tension to the anus. The colon and anal canal were interruptedly sutured using the absorbable 3-0 thread under assistance of an anal ligation device. The drainage tubes of the anal canal were placed across the coloanal anastomotic stoma.

The abdomen was closed, and an ileostomy was performed prophylactically. The classical approach was performed with Step 1 (transabdominal TME), Step 2 (transanal ISR) and Step 4 (abdominal closure), whereas the modified approach included Step 1 but only extending to the superior border of the anterior prostate and posterior coccygeal and then the perineal procedure was performed including Step 2, Step 3 (retrograde transanal TME) and Step 4.

Histopathological reports included TNM staging systems and other tumor prognostic factors, such as the status of circumferential resection margin (CRM) and distal margin. The CRM was considered to be involved when the tumor was within 1 mm of the resected CRM.

Each freshly excised specimen was evaluated by an experienced pathologist before formalin fixation. Macroscopic assessments of the resected specimen were made as follows:

Complete: intact mesorectum with only minor irregularities of a smooth mesorectal surface is observed macroscopically. No defect is deeper than 5 mm, and there is no coning toward the distal margin of the specimen. There is a smooth circumferential resection margin on slicing.

Nearly complete: moderate bulk to the mesorectum, but with irregularity of the mesorectum surface is observed macroscopically. Moderate coning of the specimen is allowed. At no site is the muscularis propria visible, with the exception of the insertion of the levator muscles.

Incomplete: little bulk to the mesorectum, with defects down onto the muscularis propria and/or very irregular circumferential resection margin is observed macroscopically.

Postoperative complications represent all complications that were recorded, and the Clavien-Dindo grade (grades I-V) was used to classify the complications within 30 d postoperatively[9].

The patients were recommended to receive postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy based on pTNM staging 3 wk after surgery. Radiation therapy fields should include the tumor bed, which should be defined by preoperative radiologic imaging and/or surgical clips. Radiation doses should be: 45-50 Gy in 25-28 fractions. 5-FU-based chemotherapy should be delivered concurrently with radiation. The chemotherapy regimen of FOLFOX6, m FOLFOX6 or XELOX was recommended to patients with TNM stage II or III. Six patients received postoperative adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, and 48 patients received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy.

Seven of the 115 patients were lost to follow-up. Patients were followed by serial clinical examination and carcinoembryonic antigen assessment every 3-6 mo for 2 year and then every 6 mo for a total of 5 year. Chest/abdominal/pelvic CT scanning was performed every 6-12 mo for up to 5 year. Colonoscopy was performed every 1 year. Local recurrence was defined as the first clinical, radiologic and/or pathologic evidence of a tumor of the same histological type within the pelvis. Distant recurrence was defined as clinical, radiologic and/or pathologic evidence of systemic disease outside the pelvis, at sites including but not limited to the liver, lungs, and para-aortic region.

Anal sphincter function was evaluated at 1 year after operation. Anorectal manometry was used to estimate anal function, and incontinence status was assessed by Wexner’s score[10] and Kirwan’s classification[11].

All data were analyzed using SPSS statistics software (version 21.0; Chicago, IL, United States). Quantitative data that followed a normal distribution are presented as mean ± SD and were compared by the t-test. Quantitative data that followed a non-normal distribution are presented as median (range) and were compared by Mann-Whitney U test. Comparisons were performed using the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. In addition, the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare the Clavien-Dindo classifications of the two groups. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Overall survival was defined as the time from the date of surgery to the date of death or date of last follow-up for living patients. All of the tests were two-sided with a level of significance set at P < 0.05.

Successful sphincter preservation was achieved for all of the 115 male patients with lower rectal cancer. Among these patients, 41 patients underwent a classical approach (group A) and 74 patients underwent a modified approach with retrograde transanal TME (group B). There were no differences in age, ASA score, BMI, intertuberous diameter, distance of tumors from the anal verge, tumor diameter, rate of laparoscopy for abdominal operation, operators, pT stage or TNM stage between groups A and B (Table 1). We performed more “ostomy” procedures in group B (97.3%, 72/74) compared with group A (43.9%, 18/41; P = 0.000) to reduce the rate of anastomostic leakage. Twenty-four and forty-five patients had stage cTNM II-III cancer in groups A and B, respectively. Clinically, neoadjuvant radiotherapy was applied more frequently in group B (35.6%, 16/45) than in group A (12.5%, 3/24; P = 0.041). Four patients had down-staging. In group A, 26 and 29 patients were suggested to receive adjuvant radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy, respectively. These numbers were 34 and 50 in group B, respectively. However, only some of them actually accepted adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy (Table 1).

| Variable | Group A, n = 41 | Group B, n = 74 | P value |

| Age in yr1 | 62.4 ± 11.2 | 59.0 ± 12.6 | 0.630 |

| ASA score | 0.787 | ||

| 1 | 6 (14.6) | 8 (10.8) | |

| 2 | 24 (58.5) | 43 (58.1) | |

| 3 | 11 (26.8) | 23 (31.1) | |

| BMI1 | 24.8 ± 2.3 | 25.0 ± 2.8 | 0.193 |

| Intertuberous diameter in mm2 | 98 (83-110) | 99 (86-111) | 0.426 |

| Distance of tumors from the anal verge in mm2 | 4 (0.5-5) | 4 (1-5) | 0.160 |

| Tumor diameter in mm2 | 50 (40-70) | 50 (40-70) | 0.679 |

| Laparoscopy for abdominal operation | 17 (41.5) | 43 (58.1) | 0.087 |

| Ostomy | 18 (43.9) | 72 (97.3) | 0.000 |

| Operators | 0.815 | ||

| A | 26 (63.4) | 51 (68.9) | |

| B | 9 (22.0) | 13 (17.6) | |

| C | 6 (14.6) | 10 (13.5) | |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 3 (12.5) | 16 (35.6) | 0.041 |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 2 (7.7) | 4 (11.8) | 0.602 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 16 (55.2) | 32 (64.0) | 0.439 |

| pT | 0.458 | ||

| pT1 | 2 (4.9) | 4 (5.4) | |

| pT2 | 12 (29.3) | 30 (40.5) | |

| pT3 | 27 (65.9) | 40 (54.1) | |

| TNM stage | 0.189 | ||

| Stage I | 12 (29.3) | 28 (37.8) | |

| Stage II | 13 (31.7) | 29 (39.2) | |

| Stage III | 16 (39.0) | 17 (23.0) |

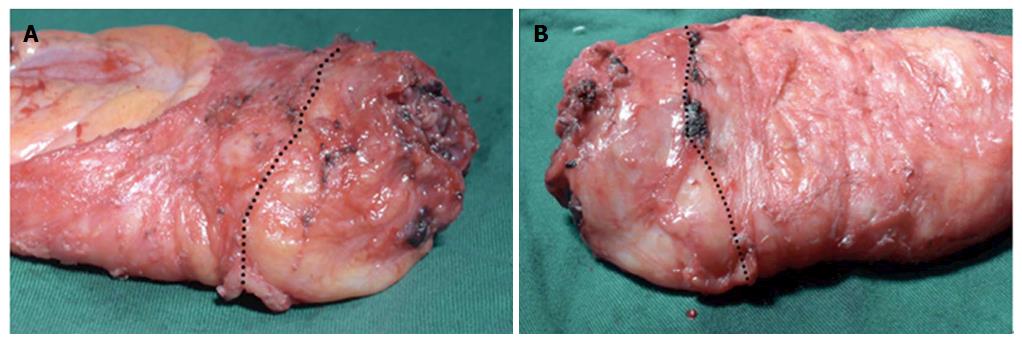

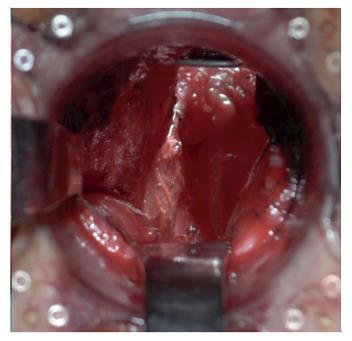

In this study, we assessed the surgery quality in the two groups by evaluating the operative time, the completeness of distal mesorectum and total mesorectum, circumferential resection margin, and distal margin. The operative time in group B (240 min, range: 160-330 min) was significantly shorter than that in group A (280 min, range: 200-360 min; P = 0.000). Moreover, compared with group A, the resected specimen in group B had a superior TME quality (Figure 3). The rates of complete distal mesorectum and complete total mesorectum were 100.0% and 90.5% in group B, and these were significantly higher than those in group A (75.6%, P = 0.000 and 70.7%, P = 0.008, respectively). There were no differences in the involvement of the circumferential resection margin and distal margin between the two groups (Table 2). The completion status of the surgery on the pelvic floor (the location of the distal rectum) could be clearly observed via the anus after removal of the specimen (Figure 4).

| Variable | Group A, n = 41 | Group B, n = 74 | P value |

| Total operating time in min2 | 280 (200-360) | 240 (160-330) | 0.000 |

| Blood loss in mL2 | 80 (20-500) | 60 (20-300) | 0.184 |

| Hospital stays after operation2 | 8 (7-23) | 8 (6-19) | 0.341 |

| Distance of tumors from distal margin in mm1 | 16.9 ± 5.3 | 17.9 ± 4.9 | 0.466 |

| Distal mesorectum | 0.000 | ||

| Complete | 31 (75.6) | 74 (100) | |

| Nearly complete | 7 (17.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Incomplete | 3 (7.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Total mesorectum | 0.008 | ||

| Complete | 29 (70.7) | 67 (90.5) | |

| Nearly complete | 9 (22.0) | 7 (9.5) | |

| Incomplete | 3 (7.3) | 0 | |

| Distal involvement | 1.000 | ||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Negative | 41 (100) | 74 (100) | |

| Circumferential resection margin | 0.543 | ||

| Positive | 2 (4.9) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Negative | 39 (95.1) | 72 (97.3) |

There were no perioperative deaths in this study, but 41 cases experienced postoperative complications, including anastomotic leakage in 4 cases, anastomotic stricture in 18 cases, early postoperative inflammatory intestinal obstruction in 6 cases, urinary tract infection in 5 cases, wound infection in 7 cases, and urinary retention in 8 cases. There were no differences in the incidence of postoperative complications between group A and group B (P > 0.05; Table 3).

| Variable | Group A, n = 41 | Group B, n = 74 | P value |

| Anastomotic leakage | 2 (4.9) | 2 (2.7) | 0.542 |

| Anastomotic stricture | 6 (14.6) | 12 (16.2) | 0.823 |

| Postoperative inflammatory intestinal obstruction | 2 (4.9) | 4 (5.4) | 0.903 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (2.4) | 4 (5.4) | 0.455 |

| Wound infection | 3 (7.3) | 4 (5.4) | 0.681 |

| Urinary retention | 3 (7.3) | 5 (6.8) | 0.91 |

| Clavien-Dindo classification | 0.85 | ||

| I | 5 (12.2) | 7 (9.5) | |

| II | 3 (7.3) | 10 (13.5) | |

| III | 2 (4.9) | 0 |

Functional results were recorded for 115 patients during follow-up (Table 4), and no differences were found in the values of the maximum resting pressure, maximum squeeze pressure and high-pressure zone length between the two groups preoperatively or at 1 year after operation. Similar results were observed for the Wexner continence score and Kirwan classification.

| Items | Pre-operation | 1 yr after operation | ||||

| Group A | Group B | P value | Group A | Group B | P value | |

| MRP in kPa | 12.2 ± 2.2 | 13.1 ± 3.5 | 0.126 | 8.8 ± 2.3 | 9.0 ± 2.8 | 0.087 |

| MSP in kPa | 18.0 ± 3.6 | 17.3 ± 3.0 | 0.054 | 16.3 ± 3.3 | 17.6 ± 2.8 | 0.201 |

| HZL in mm | 32.2 ± 5.1 | 34.7 ± 5.5 | 0.7 | 24.9 ± 4.5 | 24.2 ± 5.9 | 0.080 |

| Wexner score | 0.4 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.112 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | 3.6 ± 3.8 | 0.099 |

| Kirwan classification | 0.591 | 0.617 | ||||

| I | 34 (82.9) | 64 (86.5) | 15 (36.6) | 22 (29.7) | ||

| II | 7 (17.1) | 9 (12.2) | 16 (39.0) | 25 (33.8) | ||

| III | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 7 (17.1) | 19 (25.7) | ||

| IV | 0 | 0 | 3 (7.3) | 8 (10.8) | ||

| V | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

The mean duration of follow-up was 46.1 ± 25.6 mo (range: 12-122 mo), and 7 cases were lost to follow-up. Overall, 94 patients (91.3%) were followed up for more than 24 mo. No anastomotic recurrence was found in this study.

Twenty-one cases (18.3%, 21/115) experienced recurrence and metastasis. Among them, local recurrence was found in 10 cases (8.7%, 6 in group A and 4 in group B), which included pelvic lateral lymph node recurrence in 3 cases (1 underwent lateral lymph node dissection), sacrum recurrence in 4 cases, and pelvic muscles recurrence in 3 cases. Of the 115 patients, 14 patients (10.7%) experienced distant metastasis. Of these, 2 patients presented with liver metastases, 5 with lung metastases, and 7 with metastases to lymph nodes at the para-aortic region.

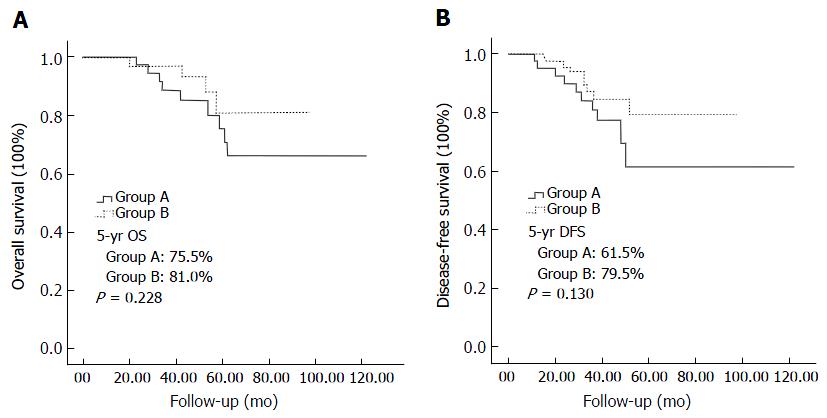

The 5-year survival rate for the study population was 78.9%, with rates of 75.5% in group A and 81.0% in group B, with no difference between the groups (P = 0.228). Group B had a lower local recurrence rate (5.4%) and higher disease-free survival rate (79.5%) comparing with group A (14.6% and 61.5%, respectively), but these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.093 and P = 0.130, respectively; Figure 5).

Numerous studies have revealed a strong relationship between a low tumor level and poor TME quality, higher positive circumferential resection margin and recurrence[4,6,12]. Leonard et al[4] reported that the incomplete TME rate was only 15.4% (2/15) when the inferior margin of the tumor above the anal verge was > 10 cm, and the rate was 28.2% (35/124) for tumors between 5 to 10 cm from the anal verge. If it was < 5 cm, the incomplete TME rate increased to 39.3% (42/107). The positive rate at the circumferential resection margin of incomplete TME was twice that of complete TME[4]. Therefore, as the low rectal cancer is closer to the anus, TME is more difficult to perform. Narrow pelvises and giant tumors have been proven to lead to surgical difficulties and increase the risk of non-curative resection[13-15]. Approaching the pelvic floor, the failure of surgical exposure may be the cause of misunderstanding the anatomic plane and inaccurate surgical dissection.

Based on these considerations, the concept of the “down-to-up” procedure has been proposed in cases where transabdominal TME is difficult[16]. This procedure reduces the effects of pelvis factors on pelvic surgery, and the operating space is expanded from the anus towards the pelvic cavity. The end of the rectum and its mesentery could be excised precisely under direct observation by retrograde transanal TME. In the 1980s, Gerald Marks developed transabdominal transanal resection (TATA) to perform TME from below to upward, but this technique required specialized instruments with limited exposure, and thus, few were able to replicate this approach[17,18]. Recently, some researchers have tried to perform TME using a transanal endoscopic operation device[19-24]. This approach has great potential value for further applications. However, it still has the disadvantages of technical difficulties associated with limited maneuverability, which means an increased learning curve for surgeons. Because of the smaller operating space under an endoscopic device, this type of surgical procedure is not suitable if the tumor is relatively large and the mesorectum is relatively thick[19]. In addition, the device is still expensive.

For better exposure of the pelvic floor from down to up and to obtain a larger operating space, we inserted a circular anal dilator into the anal canal instead of the Lone Star Retractor or transanal endoscopic operation device. We have used an anal dilator with a round-shape fixture from a classical stapler device for hemorrhoids and found that it was blocked by ischial tuberosities when the patient had a short intertuberous diameter. Now we apply an anal dilator with a papilionaceous fixture for deeper insertion into the anal canal to keep the external sphincter of the upper anal canal out of the anal dilator. This step prevents the contracting muscle from the anorectal ring from blocking the view, which facilitates observation of the pelvic floor and the accurate surgical dissection of the distal mesorectum transanally. Meanwhile, we use specially designed retractors to further extend the exposure of the operative field. This ensures the dissection is performed along the accurate anatomic plane under direct observation.

In this study, 74 patients underwent a modified approach with retrograde transanal TME (group B), and the results revealed that the operative time with the modified approach (240 min, range: 160-330 min) was significantly shorter than that with the classical approach (280 min, range: 200-360 min; P = 0.000). Moreover, the resected specimens in group B showed optimal TME quality. Compared with group A, a complete distal mesorectum and complete total mesorectum were achieved in group B (100% vs 75.6%, P = 0.000; 90.5% vs 70.7%, P = 0.008, respectively). The shorter procedure and better quality specimens observed in group B indicate that retrograde transanal TME with simple instruments facilitated the mobilization of the low rectum for male patients. Actually, several transanal surgery studies have already demonstrated that transanal TME can be performed safely with a promising amount of intact specimens and low rates of involved CRM[16,25-28]. Perdawood et al[29] reported a prospective study including 50 patients on the surgical results of transanal TME compared with laparoscopic TME (laTME) for rectal cancer. The circumferential resection margin was positive in 1 patient in their transanal TME group and 4 patients in their laTME group (P = 0.349). All patients in their transanal TME group had either complete or nearly complete specimen quality, while 4 patients in their laTME group had incomplete specimen quality (P = 0.113). Less blood loss, shorter operating time, and shorter hospital stay were observed in their transanal TME group. A meta-analysis including seven studies (transanal TME group, n = 270; laTME group, n = 303) indicated that the complete grade for the quality of the mesorectum was significantly higher for transanal TME than for laTME (OR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.02-3.01, P = 0.04) and significantly fewer patients in the transanal TME group had a positive CRM (OR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.17-0.86, P = 0.02)[30].

However, research studies on oncologic outcomes of transanal TME are still few. Rouanet et al[23] reported oncologic outcomes for a series of 30 transanal TME operations with locally advanced tumors. Overall survival rates after 12 and 24 mo were 96.6% and 80.5%, respectively. In the present study, our results revealed that group B had a lower local recurrence rate and higher 5-yr disease-free survival rate compared with group A (5.4% vs 14.6% and 79.5% vs 61.5%, respectively). However, these differences were not statistically significant, possibly due to the small number of patients in this study.

Furthermore, we also observed the anal sphincter function and incontinence status 1 year after operation. No differences were found between the two groups, and the mean Wexner score in group B (retrograde transanal TME) was 3.6, which was also close to that in other transanal TME studies[31,32]. This modified approach with retrograde transanal TME does not compromise anal function compared with the conventional approach for patients with low rectal cancer.

Taken together, the results of this study indicated that the modified approach is better than the classical approach for sphincter-preserving surgery in male patients with low rectal cancers, especially in those with bulky tumors. However, this study is limited mainly in its retrospective design, and a larger number of patients would be ideal. Additionally, only a few of the patients received neoadjuvant chemoradiation in this study because of rejections. In conclusion, our results indicate that the procedure of retrograde transanal TME with simple instruments can overcome the so-called the “no man’s area” in rectal surgery to ensure TME completion at the distal rectum and can achieve a better quality specimen without lowering anorectal function.

We would like to thank Xiu-Ling Wu and Zhong-Min Lin, Department of Pathology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University for their assistance in pathologic assessment, and Xin-Jun Yang, Department of Preventive Medicine, the School of Public Health and Management, Wenzhou Medical University, for her assistance in statistical analysis.

High-quality total mesorectal excision (TME) is of great importance in curing patients with rectal cancer. However, distal mesorectal excision is difficult when the tumor is low, especially with a narrow pelvis and large tumor volume.

Many studies have suggested that a transanal approach may resolve the issues derived from a narrow pelvis and large tumor volume. This procedure provides several advantages over conventional excision by offering much improved visualization and exposure. It greatly facilitates distal rectal dissection and provides high-quality TME specimens.

Most studies about the transanal approach used a specialized platform, such as a transanal endoscopic operation platform. However, the application of transanal endoscopic operation has remained limited due to the high costs of such platforms and the complexity for surgeons. The authors explored the application of simple instruments including modified retractors and an anal dilator with a papilionaceous fixture to perform transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME). These simple instruments facilitate observation of the pelvic floor and accurate surgical dissection of the distal mesorectum transanally.

The study results suggest that the modified approach with simple instruments achieved a shorter operative time and better quality of mesorectal excision, as compared with the classical approach. It is a better approach for sphincter-preserving surgery in male patients with low rectal cancers, especially in those with bulky tumors. This procedure may be a safe, effective and economical alternative for taTME.

The intersphincteric resection technique allows a sphincter-saving resection for ultralow rectal cancer, mainly excluding cases with infiltration of the external sphincter. This technique consists of removing part of or the whole internal anal sphincter to obtain free distal margin. TME, which considers the rectum and mesorectum as one lymphovascular structure, requires its excision within an intact fascia propria. TaTME is a procedure in which the rectum is mobilized transanally in a retrograde fashion. It reduces the effects of pelvis factors on pelvic surgery, and the end of the rectum and its mesentery could be excised precisely under direct observation.

The authors have developed a unique surgical method for transanal TME using simple instruments. The reviewer considers that their procedure is potentially good and the manuscript is well written. This is a very interesting study about a surgical technique that although described several decades ago, is only now being widely adopted by colorectal surgeons around the world.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Allaix ME, Elpek GO, Horesh N, Kai K, Wani IA S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Heald RJ. The ‘Holy Plane’ of rectal surgery. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:503-508. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yang Q, Xiu P, Qi X, Yi G, Xu L. Surgical margins and short-term results of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for low rectal cancer. JSLS. 2013;17:212-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Williams NS. The rectal ‘no man’s land’ and sphincter preservation during rectal excision. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1749-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leonard D, Penninckx F, Fieuws S, Jouret-Mourin A, Sempoux C, Jehaes C, Van Eycken E; PROCARE, a multidisciplinary Belgian Project on Cancer of the Rectum. Factors predicting the quality of total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2010;252:982-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hiranyakas A, da Silva G, Wexner SD, Ho YH, Allende D, Berho M. Factors influencing circumferential resection margin in rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:298-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Garlipp B, Ptok H, Schmidt U, Stübs P, Scheidbach H, Meyer F, Gastinger I, Lippert H. Factors influencing the quality of total mesorectal excision. Br J Surg. 2012;99:714-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nicholson G, Knol J, Houben B, Cunningham C, Ashraf S, Hompes R. Optimal dissection for transanal total mesorectal excision using modified CO2 insufflation and smoke extraction. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:O265-O267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Araujo SE, Crawshaw B, Mendes CR, Delaney CP. Transanal total mesorectal excision: a systematic review of the experimental and clinical evidence. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:69-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24829] [Article Influence: 1182.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77-97. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kirwan WO, Turnbull RB Jr, Fazio VW, Weakley FL. Pullthrough operation with delayed anastomosis for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1978;65:695-698. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Oh SY, Kim YB, Paek OJ, Suh KW. Does total mesorectal excision require a learning curve? Analysis from the database of a single surgeon’s experience. World J Surg. 2011;35:1130-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | García-Granero E, Faiz O, Flor-Lorente B, García-Botello S, Esclápez P, Cervantes A. Prognostic implications of circumferential location of distal rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:650-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Targarona EM, Balague C, Pernas JC, Martinez C, Berindoague R, Gich I, Trias M. Can we predict immediate outcome after laparoscopic rectal surgery? Multivariate analysis of clinical, anatomic, and pathologic features after 3-dimensional reconstruction of the pelvic anatomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:642-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | You JF, Tang R, Changchien CR, Chen JS, You YT, Chiang JM, Yeh CY, Hsieh PS, Tsai WS, Fan CW. Effect of body mass index on the outcome of patients with rectal cancer receiving curative anterior resection: disparity between the upper and lower rectum. Ann Surg. 2009;249:783-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de Lacy AM, Rattner DW, Adelsdorfer C, Tasende MM, Fernández M, Delgado S, Sylla P, Martínez-Palli G. Transanal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) rectal resection: “down-to-up” total mesorectal excision (TME)--short-term outcomes in the first 20 cases. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3165-3172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Marks G, Mohiuddin M, Rakinic J. New hope and promise for sphincter preservation in the management of cancer of the rectum. Semin Oncol. 1991;18:388-398. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Atallah S. Transanal total mesorectal excision: full steam ahead. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang H, Zhang YS, Jin XW, Li MZ, Fan JS, Yang ZH. Transanal single-port laparoscopic total mesorectal excision in the treatment of rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Atallah S, Albert M, DeBeche-Adams T, Nassif G, Polavarapu H, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery for total mesorectal excision (TAMIS-TME): a stepwise description of the surgical technique with video demonstration. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:321-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lacy AM, Adelsdorfer C. Totally transrectal endoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME). Colorectal Dis. 2011;13 Suppl 7:43-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Velthuis S, van den Boezem PB, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA, Sietses C. Feasibility study of transanal total mesorectal excision. Br J Surg. 2013;100:828-831; discussion 831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rouanet P, Mourregot A, Azar CC, Carrere S, Gutowski M, Quenet F, Saint-Aubert B, Colombo PE. Transanal endoscopic proctectomy: an innovative procedure for difficult resection of rectal tumors in men with narrow pelvis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:408-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Meng W, Lau K. Synchronous laparoscopic low anterior and transanal endoscopic microsurgery total mesorectal resection. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2014;23:70-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Marks JH, Montenegro GA, Salem JF, Shields MV, Marks GJ. Transanal TATA/TME: a case-matched study of taTME versus laparoscopic TME surgery for rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20:467-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Veltcamp Helbach M, Deijen CL, Velthuis S, Bonjer HJ, Tuynman JB, Sietses C. Transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal carcinoma: short-term outcomes and experience after 80 cases. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tuech JJ, Karoui M, Lelong B, De Chaisemartin C, Bridoux V, Manceau G, Delpero JR, Hanoun L, Michot F. A step toward NOTES total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: endoscopic transanal proctectomy. Ann Surg. 2015;261:228-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lacy AM, Tasende MM, Delgado S, Fernandez-Hevia M, Jimenez M, De Lacy B, Castells A, Bravo R, Wexner SD, Heald RJ. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: Outcomes after 140 Patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:415-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Perdawood SK, Al Khefagie GA. Transanal vs laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: initial experience from Denmark. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ma B, Gao P, Song Y, Zhang C, Zhang C, Wang L, Liu H, Wang Z. Transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of oncological and perioperative outcomes compared with laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Elmore U, Fumagalli Romario U, Vignali A, Sosa MF, Angiolini MR, Rosati R. Laparoscopic anterior resection with transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: preliminary experience and impact on postoperative bowel function. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:364-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dumont F, Goéré D, Honoré C, Elias D. Transanal endoscopic total mesorectal excision combined with single-port laparoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:996-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |