Published online Jul 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4823

Peer-review started: February 14, 2017

First decision: March 16, 2017

Revised: April 3, 2017

Accepted: May 4, 2017

Article in press: May 4, 2017

Published online: July 14, 2017

Processing time: 150 Days and 17.7 Hours

To determine the predictive factors and impact of body weight loss on postgastrectomy quality of life (QOL).

We applied the newly developed integrated questionnaire postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale-45, which consists of 45 items including those from the Short Form-8 and Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale instruments, in addition to 22 newly selected items. Between July 2009 and December 2010, completed questionnaires were received from 2520 patients with curative resection at 1 year or more after having undergone one of six types of gastrectomy for Stage I gastric cancer at one of 52 participating institutions. Of those, we analyzed 1777 eligible questionnaires from patients who underwent total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y procedure (TGRY) or distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I (DGBI) or Roux-en-Y (DGRY) procedures.

A total of 393, 475 and 909 patients underwent TGRY, DGRY, and DGBI, respectively. The mean age of patients was 62.1 ± 9.2 years. The mean time interval between surgery and retrieval of the questionnaires was 37.0 ± 26.8 mo. On multiple regression analysis, higher preoperative body mass index, total gastrectomy, and female sex, in that order, were independent predictors of greater body weight loss after gastrectomy. There was a significant difference in the degree of weight loss (P < 0.001) among groups stratified according to preoperative body mass index (< 18.5, 18.5-25 and > 25 kg/m2). Multiple linear regression analysis identified lower postoperative body mass index, rather than greater body weight loss postoperatively, as a certain factor for worse QOL (P < 0.0001) after gastrectomy, but the influence of both such factors on QOL was relatively small (R2, 0.028-0.080).

While it is certainly important to maintain adequate body weight after gastrectomy, the impact of body weight loss on QOL is unexpectedly small.

Core tip: Our study of almost 1800 gastrectomy patients revealed that higher preoperative body mass index, total gastrectomy, and female sex were independent predictors of greater body weight loss after gastrectomy. Moreover, we determined lower postoperative body mass index, rather than greater postoperative weight loss, as a certain factor of worse quality of life (QOL), although the effect was not substantial. We believe that this contribution is theoretically and practically relevant in the current context of gastric cancer treatment and recovery because early diagnosis and improved treatments have led to increased long-term survival postgastrectomy, highlighting the need for better QOL.

- Citation: Tanabe K, Takahashi M, Urushihara T, Nakamura Y, Yamada M, Lee SW, Tanaka S, Miki A, Ikeda M, Nakada K. Predictive factors for body weight loss and its impact on quality of life following gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(26): 4823-4830

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i26/4823.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4823

Despite its gradually decreasing incidence, gastric cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer death in the world[1]. Surgical resection and regional lymphadenectomy are the only curative options for patients with localized gastric tumors[2-4]. As early diagnosis and improved treatment have led to longer-term survival, patients are now more aware of the morbidities associated with gastrectomy, which is called postgastrectomy syndrome. Indeed, the gastrectomized patients may experience various nutritional and functional problems that interfere with their quality of life (QOL)[5-7]. Loss of body weight is a common complaint after gastrectomy, and is thought as one of few objective indices to measure the well-being of postgastrectomy patients. Some reports suggest that the type of gastrectomy is a certain predictor of postoperative weight loss[6,8,9], however, other predictive factors for postoperative weight loss has yet not been determined. Though the low body mass index (BMI) as well as body weight loss is often identified after gastrectomy and may affects the QOL after gastrectomy[10], their detail implication on the QOL has not been clarified.

The aim of the present study was to determine the predictive factors for postoperative weight loss and to investigate the impact of body weight loss and low BMI on the QOL in patients after gastrectomy using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45, which was established specifically to assess symptoms, living status and QOL among patients after gastrectomy[11].

The PGSAS study, a surveillance study involving 52 institutions, was conducted by the Japanese Postgastrectomy Syndrome Working Party (JPGSWP) and approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions. After completion of the informed consent process, patients were enrolled in this study if they met the following eligibility criteria: 20-75 years of age, histologically proven Stage I gastric cancer based on the 13th edition of the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma[12], curative resection at least 1 year after surgery, no signs of recurrence at the point of assessment, and no other active malignancy.

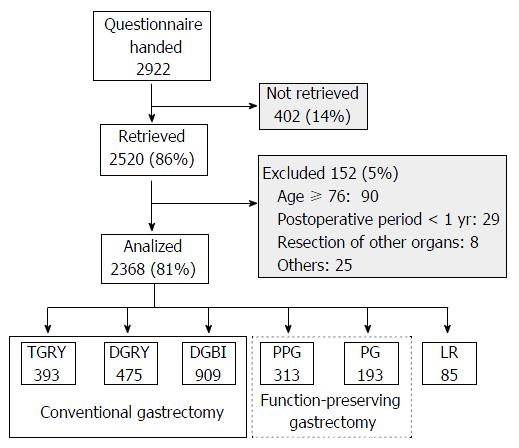

The PGSAS-45 questionnaire consists of 45 questions, with 8 items from the Short Form-8 (SF-8)[13], 15 items from the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale[14], and 22 clinically important items determined by the JPGSWP. Patients were given the questionnaire together with a stamped and addressed envelope in the outpatient clinic and were asked to complete questionnaire and return it by post to the data center. Of the 2922 patients to whom questionnaires were given during July 2009 to December 2010, 2520 (86%) responded and 2368 (81%) were confirmed to be eligible for the original study. Of these, the data from 1777 patients who underwent total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y (TGRY) and distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I (DGBI) or Roux-en-Y (DGRY) were analyzed in this study.

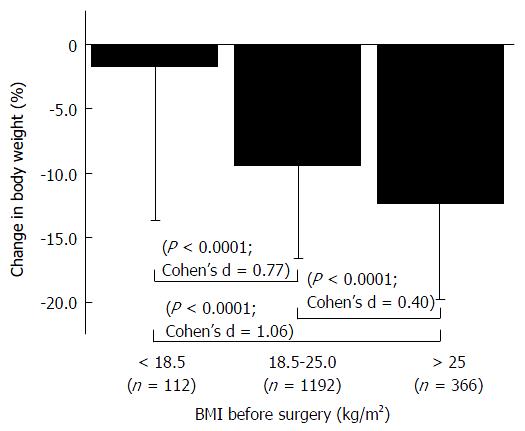

The degree of body weight loss was compared among the three relevant preoperative BMI groups (BMI, < 18.5, 18.5-25 and > 25 kg/m2) by multiple comparisons. Multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the factors affecting body weight loss after surgery, and to study the impact of the change in body weight and postoperative BMI on QOL. A P value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. To evaluate effect sizes, Cohen’s d, standardization coefficient of regression (β) and coefficient of determination (R2) were used. Interpretation of effect sizes were ≥ 0.2 small, ≥ 0.5 medium, and ≥ 0.8 large in Cohen’s d; ≥ 0.1 small, ≥ 0.3 medium, and ≥ 0.5 large in β; ≥ 0.02 small, ≥ 0.13 medium, and ≥ 0.26 large in R2. All statistical analyses were performed by biostatisticians who primarily used Stat View for Windows Ver. 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

A CONSORT flowchart of the PGSAS study is shown in Figure 1. A total of 1777 patients (1188 men; 66.9%) who underwent conventional gastrectomy were enrolled in this study. The mean age of patients was 62.1 ± 9.2 years. The numbers of patients undergoing each operative procedure were as follows: TGRY, 393; DGRY, 475; and DGBI, 909. The mean time interval between surgery and retrieval of the questionnaires was 37.0 ± 26.8 mo, and the mean body weight loss among postgastrectomy patients was 9.5% ± 8.0% at that time (Table 1).

| Sex [male: n (%)] | 1188 (66.9) |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 62.1 ± 9.2 |

| Type of gastrectomy (n: TGRY/DGBI/DGRY) | 393/909/475 |

| Period after gastrectomy (mo: mean ± SD) | 37.0 ± 26.8 |

| Change in body weight (%, mean ± SD) | -9.5 ± 8.0 |

| Preoperative BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 22.8 ± 3.1 |

| Postoperative BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 20.6 ± 2.8 |

| Approach (n, open/laparoscopic) | 1102 ± 664 |

| Preservation of celiac branch of vagus (Y/N) | 173/1567 |

The PGSAS-45 is an integrated questionnaire for assessing the symptoms, the living status and the QOL in patients after gastrectomy, as described previously[11]. The structure of the PGSAS-45 is shown in Table 2. QOL scores in the PGSAS-45 were obtained for two subdomains: dissatisfaction and the SF-8 items. The dissatisfaction subdomain consists of four outcome measures based on symptoms (item 43), meals (item 44), working (item 45), and daily life subscale (mean of the item 43-45). The SF-8 consists of eight items and generates two summary measures, the physical component summary and the mental component summary. The mean values of main outcome measures are shown in Table 3.

| Domains | Subdomains | Items | Subscales | |

| QOL | SF-8 (QOL) | 1 | Physical functioning1 | Physical component summary1 (item 1-8) |

| 2 | Role physical1 | Mental component summary1 (item 1-8) | ||

| 3 | Bodily pain1 | |||

| 4 | General health1 | |||

| 5 | Vitality1 | |||

| 6 | Social functioning1 | |||

| 7 | Role emotional1 | |||

| 8 | Mental health1 | |||

| Symptoms | GSRS (Symptoms) | 9 | Abdominal pains | Esophageal reflux subscale (item 10, 11, 13, 24) |

| 10 | Heartburn | Abdominal pain subscale (item 9, 12, 28) | ||

| 11 | Acid regurgitation | Meal-related distress subscale (item 25-27) | ||

| 12 | Sucking sensations in the epigastrium | Indigestion subscale (item 14-17) | ||

| 13 | Nausea and vomiting | Diarrhea subscale (item 19, 20, 22) | ||

| 14 | Borborygmus | Constipation subscale (item 18, 21, 23) | ||

| 15 | Abdominal distension | Dumping subscale (item 30, 31, 33) | ||

| 16 | Nausea and vomiting | |||

| 17 | Increased flatus | Total symptom scale (above seven subscales) | ||

| 18 | Decreased passage of stools | |||

| 19 | Increased passage of stools | |||

| 20 | Loose stools | |||

| 21 | Hard stools | |||

| 22 | Urgent need for defecation | |||

| 23 | Feeling of incomplete evacuation | |||

| Symptoms | 24 | Bile regurgitation | ||

| 25 | Sense of foods sticking | |||

| 26 | Postprandial fullness | |||

| 27 | Early satiation | |||

| 28 | Lower abdominal pains | |||

| 29 | Number and type of early dumping symptoms | |||

| 30 | Early dumping general symptoms | |||

| 31 | Early dumping abdominal symptoms | |||

| 32 | Number and type of late dumping symptoms | |||

| 33 | Late dumping symptoms | |||

| Living status | Meals (amount) 1 | 34 | Ingested amount of food per meal1 | |

| 35 | Ingested amount of food per day1 | |||

| 36 | Frequency of main meals | |||

| 37 | Frequency of additional meals | |||

| Meals (quality) | 38 | Appetite1 | Quality of ingestion subscale1 (item 38-40) | |

| 39 | Hunger feeling1 | |||

| 40 | Satiety feeling1 | |||

| Meals (amount) 2 | 41 | Necessity for additional meals | ||

| Social activity | 42 | Ability for working | ||

| QOL | Dissatisfaction (QOL) | 43 | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | Dissatisfaction for daily life subscale (item 43-45) |

| 44 | Dissatisfaction at the meals | |||

| 45 | Dissatisfaction at working |

| Subdomains | Item in PGSAS-45 | Main outcomes measures | Scale | mean ±SD |

| Dissatisfaction | 43 | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | Five-point Likert scale | 1.87 ± 0.95 |

| 44 | Dissatisfaction at the meals | 1.13 | ||

| 45 | Dissatisfaction at working | 1.79 ± 0.97 | ||

| 43-45 | Dissatisfaction for daily life subscale | 0.87 | ||

| SF-8 | 1-8 | Physical component summary1 | Five or six-point Likert scale | 50.4 ± 5.6 |

| 1-8 | Mental component summary1 | 49.7 ± 5.8 |

To clarify the predictive factors affecting change in body weight after surgery, multiple regression analysis was performed. In order of significance, higher preoperative BMI, type of gastrectomy (TGRY) and female sex were the independent predictors for postoperative weight loss (Table 4).

| Variables | Change in body weight | |

| β | P value | |

| Type of gastrectomy (DGBI) | 0.204 | < 0.0001 |

| Type of gastrectomy (DGRY) | 0.116 | < 0.0001 |

| Postoperative period (mo) | (-0.02) | NS |

| Age (yr) | (-0.04) | 0.0746 |

| Gender (male) | 0.120 | < 0.0001 |

| Preoperative BMI (kg/m2) | -0.3561 | < 0.0001 |

| Approach (Laparoscopic) | (0.01) | NS |

| Celiac branch of vagus (Preserved) | (0.074) | 0.0010 |

| R2 (P value) | 0.216 | < 0.0001 |

| The interpretation of effect size | β | R2 |

| None-very small | < (0.100) | < (0.020) |

| Small | > 0.100 | > 0.020 |

| Medium | > 0.3001 | > 0.1301 |

| Large | > 0.500 | > 0.260 |

Considering that preoperative BMI was the most influential factor affecting weight loss postoperatively, we compared the degree of weight loss among three relevant preoperative BMI groups: < 18.5; 18.5-25; and 25 < (kg/m2) (Figure 2). There was a significant difference between each group (P < 0.0001) with a certain effect size in terms of Cohen’s d. The patients with higher BMI (> 25 kg/m2) exhibited the greatest weight loss (12.3%) among the groups, while the degree of weight loss in patients with lower BMI < (18.5) was spare (2%).

Finally, we performed multiple regression analysis to compare the influence on postoperative QOL between body weight loss and low postoperative BMI (Tables 5 and 6). The low postoperative BMI significantly affected on all QOL outcome measures with small but clinically meaningful effect size in terms of standardized partial regression coefficient (β), while the body weight loss only affected on some of QOL outcome measures with smaller effect size in β (approximately of half value compared to that of postoperative BMI). In addition, coefficient of determination R2, which indicates the aggregated impact of body weight loss and low postoperative BMI on the QOL, were relatively small for each QOL outcome measures.

| Variables | Ability for working | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | Dissatisfaction at the meals | Dissatisfaction at working | Dissatisfaction for daily life subscale | PCS | MCS | |||||||

| β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | |

| Postoperative BMI (kg/m2) | -0.134 | < 0.0001 | -0.189 | < 0.0001 | 0.216 | < 0.0001 | -0.185 | < 0.0001 | -0.231 | < 0.0001 | 0.148 | < 0.0001 | 0.109 | < 0.0001 |

| Change in body weight (%) | (-0.081) | 0.0018 | (-0.073) | 0.0040 | -0.112 | < 0.001 | (-0.097) | <0.0001 | -0.109 | < 0.0001 | (0.047) | 0.066 | (0.025) | NS |

| R2 (P value) | 0.031 | < 0.0001 | 0.048 | < 0.0001 | 0.073 | < 0.001 | 0.054 | < 0.0001 | 0.080 | < 0.0001 | 0.028 | < 0.0001 | (0.014) | < 0.0001 |

| The interpretation of effect size | β | R2 |

| None-very small | < (0.100) | < (0.020) |

| Small | > 0.100 | > 0.020 |

| Medium | > 0.300 | > 0.130 |

| Large | > 0.500 | > 0.260 |

This study identified the causal factors affecting body weight loss after gastrectomy and investigated the impact of body weight loss on the postoperative QOL using the PGSAS-45 questionnaire, which was recently developed to assess the QOL following gastrectomy. Our results identified higher preoperative BMI as the most influential factor affecting postoperative weight loss, followed by the type of gastrectomy performed (TGRY) and female sex, in order of significance. Moreover, the patients with higher BMI (> 25 kg/m2) preoperatively exhibited the largest postoperative weight loss among three relevant preoperative BMI groups. The patients with low postoperative BMI experienced worse QOL than those with greater body weight loss, though the aggregated impact of low BMI and excess body weight loss on the QOL postoperatively was relatively smaller than generally considered.

Loss of body weight after gastrectomy is thought to be caused by multiple factors, including decreased serum ghrelin[15], reduced food intake due to various abdominal symptoms, and disorder of digestive and absorptive function due to pancreatic exocrine insufficiency or postcibal pancreaticobilliary asynchrony. The degree of weight loss was also affected by the type of gastrectomy employed[15-19]. Additionally, body weight loss is also related to tumor progression or chemotherapy after surgery. In this study, we focused on Stage I patients in order to exclude the influence of other factors that may influence the postoperative body weight, and to isolate the effect of the surgical procedures. The findings of present study that patients undergoing TGRY had a greater body weight loss compared to those undergoing DGBI or DGRY were compatible with the previous reports[19,20]. However, the influence of the other surgical procedures such as laparoscopic approach or preservation of celiac branch of vagus, which maintains the postprandial motility of the duodenum and jejunum[21] and attenuates a dumping syndrome[22], were insignificant as for effect size, β.

Recent analyzes of specific disease processes, including sarcopenia and metabolic diseases, have identified the importance of evaluating not only BMI but also body component composition, such as body fat and skeletal muscle[23-26]. Siervo et al[27] also reported that body composition varies with BMI, age and sex. Although a significant reduction in body fat has been reported after gastrectomy, several studies indicated that the reduction in skeletal muscle mass was smaller than reductions in the volume of body fat[28-31]. These previous findings may, in part, explain the smaller body weight loss in patients with low BMI (< 18.5), in which, the proportion of the skeletal muscle supposed to be larger than those of the other relevant preoperative BMI groups.

Body weight loss is considered to be one of the objective index which resulting in worse QOL after gastrectomy[5,8,32,33], and also loss of body weight is associated with intolerance to adjuvant chemotherapy[34]. However, in clinical setting, excess body weight loss is not always accompanied with worse QOL, therefore, precise features of the impact of body weight loss on the postoperative QOL should be investigated. For this purpose, we studied the impact of body weight loss as well as postoperative BMI on the postgastrectomy QOL using the PGSAS-45 questionnaire, which is the first questionnaire developed to specifically measure QOL in gastrectomized patients[11,35-38], by multiple regression analysis. The results of our study demonstrated that the preoperative BMI rather than the degree of body weight loss was the most influential predictor of worse QOL after gastrectomy. The low postoperative BMI significantly affected on all QOL outcome measures, though the body weight loss only affected few QOL outcome measures with smaller effect size in terms of β. The aggregated impact of low BMI and body weight loss was unexpectedly small for each QOL outcome measures in terms of R2. There may be other factors influencing worse QOL postgastrectomy, and future work should focus on investigation of other possible factors.

Despite above mentioned results, both to maintain postoperative body weight and to avoid low BMI seem yet important for better QOL after gastrectomy, therefore, enhanced perioperative nutritional management should be required particularly in patients with low preoperative BMI.

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. This study was not a prospective study and the investigation was performed at a single point in time postoperatively. We focused on long-term QOL, more than 1 year after gastrectomy based on previous findings that most QOL measures are stable at > 1 year postoperatively[39]. However, such QOL measurements at a single point in time may be insufficient to reflect the true impact of body weight loss. Further prospective and chronological studies assessing QOL over short- and longer-term periods after gastrectomy are required.

The authors thank all of the physicians who participated in this study and the patients whose cooperation made it possible.

Body weight loss, a common complaint after gastrectomy, is likely associated with various factors such as tumor progression and chemotherapy. While several reports indicated that the type of gastrectomy may be a determinant of postoperative weight loss, other risk factors have yet to be determined. In the present study, they focused only on patients with Stage I gastric cancer, so as to evaluate the impact of the surgical procedure without the confounding effect of other factors.

Previous reports indicated that the type of gastrectomy is a certain postoperative weight loss, suggesting that total gastrectomy resulted in greater weight loss. Additionally, patients with excess weight loss after gastrectomy were shown to have lower performance status and difficulty in continuing chemotherapy. However, few reports have analyzed the relationship between postgastrectomy body weight loss and quality of life (QOL).

The authors aimed to determine the predictive factors and clarify the quality-of-life impact of postgastrectomy body weight loss and low body mass index. For this purpose, the authors used the postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale-45, which was established specifically to evaluate QOL following gastrectomy. Interestingly, the authors found that postoperative body mass index, rather than the degree of weight loss, was a predictor of worse QOL after gastrectomy, but the effect was relatively mild.

To minimize the negative effects on QOL after gastrectomy, it is better to maintain the postoperative body weight and avoid low body mass index. Postgastrectomy syndrome is a group of disorders and complications following gastrectomy. It includes early/late dumping syndrome, reflux gastritis, diarrhea, anemia, malabsorption, reflux gastritis, and weight loss.

The authors have conducted a well-written observational study. The case enrollment and variable choices were appropriate. Despite this study has the limit that QOL measures are conducted only at a single point after surgery, it has some new insights.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kirshtein B, Song WC S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25533] [Article Influence: 1823.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Mine M, Majima S, Harada M, Etani S. End results of gastrectomy for gastric cancer: effect of extensive lymph node dissection. Surgery. 1970;68:753-758. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Maruyama K, Okabayashi K, Kinoshita T. Progress in gastric cancer surgery in Japan and its limits of radicality. World J Surg. 1987;11:418-425. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1140] [Cited by in RCA: 1304] [Article Influence: 86.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Katsube T, Konnno S, Murayama M, Kuhara K, Sagawa M, Yoshimatsu K, Shiozawa S, Shimakawa T, Naritaka Y, Ogawa K. Changes of nutritional status after distal gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1864-1867. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kim AR, Cho J, Hsu YJ, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Yun YH, Kim S. Changes of quality of life in gastric cancer patients after curative resection: a longitudinal cohort study in Korea. Ann Surg. 2012;256:1008-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Karanicolas PJ, Graham D, Gönen M, Strong VE, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee J, Hur H, Kim W. Improved long-term quality of life in patients with laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with jejunal pouch interposition for early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2024-2030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Courneya KS, Karvinen KH, Campbell KL, Pearcey RG, Dundas G, Capstick V, Tonkin KS. Associations among exercise, body weight, and quality of life in a population-based sample of endometrial cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:422-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lin LL, Brown JC, Segal S, Schmitz KH. Quality of life, body mass index, and physical activity among uterine cancer patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1027-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nakada K, Ikeda M, Takahashi M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M. Characteristics and clinical relevance of postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS)-45: newly developed integrated questionnaires for assessment of living status and quality of life in postgastrectomy patients. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 13th ed. Kanehara. 1999;. |

| 13. | Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1003-1012. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Takachi K, Doki Y, Ishikawa O, Miyashiro I, Sasaki Y, Ohigashi H, Murata K, Nakajima H, Hosoda H, Kangawa K. Postoperative ghrelin levels and delayed recovery from body weight loss after distal or total gastrectomy. J Surg Res. 2006;130:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bae JM, Park JW, Yang HK, Kim JP. Nutritional status of gastric cancer patients after total gastrectomy. World J Surg. 1998;22:254-260; discussion 260-261. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Adachi S, Takeda T, Fukao K. Evaluation of esophageal bile reflux after total gastrectomy by gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary dual scintigraphy. Surg Today. 1999;29:301-306. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Melissas J, Kampitakis E, Schoretsanitis G, Mouzas J, Kouroumalis E, Tsiftsis DD. Does reduction in gastric acid secretion in bariatric surgery increase diet-induced thermogenesis? Obes Surg. 2002;12:399-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tsuburaya A, Noguchi Y, Yoshikawa T, Nomura K, Fukuzawa K, Makino T, Imada T, Matsumoto A. Long-term effect of radical gastrectomy on nutrition and immunity. Surg Today. 1993;23:320-324. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ishikawa M, Kitayama J, Kaizaki S, Nakayama H, Ishigami H, Fujii S, Suzuki H, Inoue T, Sako A, Asakage M. Prospective randomized trial comparing Billroth I and Roux-en-Y procedures after distal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:1415-1420; discussion 1421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ando H, Mochiki E, Ohno T, Kogure N, Tanaka N, Tabe Y, Kimura H, Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T. Effect of distal subtotal gastrectomy with preservation of the celiac branch of the vagus nerve to gastrointestinal function: an experimental study in conscious dogs. Ann Surg. 2008;247:976-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fujita J, Takahashi M, Urushihara T, Tanabe K, Kodera Y, Yumiba T, Matsumoto H, Takagane A, Kunisaki C, Nakada K. Assessment of postoperative quality of life following pylorus-preserving gastrectomy and Billroth-I distal gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients: results of the nationwide postgastrectomy syndrome assessment study. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:302-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Iannuzzi-Sucich M, Prestwood KM, Kenny AM. Prevalence of sarcopenia and predictors of skeletal muscle mass in healthy, older men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M772-M777. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Müller MJ, Lagerpusch M, Enderle J, Schautz B, Heller M, Bosy-Westphal A. Beyond the body mass index: tracking body composition in the pathogenesis of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Obes Rev. 2012;13 Suppl 2:6-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chung JY, Kang HT, Lee DC, Lee HR, Lee YJ. Body composition and its association with cardiometabolic risk factors in the elderly: a focus on sarcopenic obesity. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56:270-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gologanu D, Ionita D, Gartonea T, Stanescu C, Bogdan MA. Body composition in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Maedica (Buchar). 2014;9:25-32. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Siervo M, Prado CM, Mire E, Broyles S, Wells JC, Heymsfield S, Katzmarzyk PT. Body composition indices of a load-capacity model: gender- and BMI-specific reference curves. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:1245-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yoon DY, Kim HK, Kim JA, Choi CS, Yun EJ, Chang SK, Lee YJ, Park CH. Changes in the abdominal fat distribution after gastrectomy: computed tomography assessment. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:121-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mizrahi I, Beglaibter N, Simanovsky N, Lioubashevsky N, Mazeh H, Ghanem M, Chapchay K, Eid A, Grinbaum R. Ultrasound evaluation of visceral and subcutaneous fat reduction in morbidly obese subjects undergoing laparoscopic gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy, and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a prospective comparison study. Obes Surg. 2015;25:959-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yamaoka Y, Fujitani K, Tsujinaka T, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Sekimoto M. Skeletal muscle loss after total gastrectomy, exacerbated by adjuvant chemotherapy. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:382-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Park KB, Kwon OK, Yu W, Jang BC. Body composition changes after totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with delta-shaped anastomosis: a comparison with conventional Billroth I anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4286-4293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wu CW, Hsieh MC, Lo SS, Lui WY, P’eng FK. Quality of life of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma after curative gastrectomy. World J Surg. 1997;21:777-782. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Scurtu R, Groza N, Otel O, Goia A, Funariu G. Quality of life in patients with esophagojejunal anastomosis after total gastrectomy for cancer. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:367-372. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Aoyama T, Yoshikawa T, Shirai J, Hayashi T, Yamada T, Tsuchida K, Hasegawa S, Cho H, Yukawa N, Oshima T. Body weight loss after surgery is an independent risk factor for continuation of S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2000-2006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Terashima M, Tanabe K, Yoshida M, Kawahira H, Inada T, Okabe H, Urushihara T, Kawashima Y, Fukushima N, Nakada K. Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45 and changes in body weight are useful tools for evaluation of reconstruction methods following distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21 Suppl 3:S370-S378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Takiguchi N, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Inagawa S, Ueda S, Nobuoka T, Ota M, Iwasaki Y, Uchida N, Kodera Y. Long-term quality-of-life comparison of total gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy by postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS-45): a nationwide multi-institutional study. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:407-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Namikawa T, Hiki N, Kinami S, Okabe H, Urushihara T, Kawahira H, Fukushima N, Kodera Y, Yumiba T, Oshio A. Factors that minimize postgastrectomy symptoms following pylorus-preserving gastrectomy: assessment using a newly developed scale (PGSAS-45). Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:397-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Misawa K, Terashima M, Uenosono Y, Ota S, Hata H, Noro H, Yamaguchi K, Yajima H, Nitta T, Nakada K. Evaluation of postgastrectomy symptoms after distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I reconstruction using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45 (PGSAS-45). Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:675-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kobayashi D, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Koike M, Nakayama G, Nakao A. Assessment of quality of life after gastrectomy using EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22. World J Surg. 2011;35:357-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |