Published online Jun 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4407

Peer-review started: February 17, 2017

First decision: March 22, 2017

Revised: April 4, 2017

Accepted: May 19, 2017

Article in press: May 19, 2017

Published online: June 28, 2017

Processing time: 129 Days and 23.1 Hours

To determine the gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC) occurrence rate and related factors, we evaluated the follow-up results of patients confirmed to have gastric dysplasia after endoscopic resection (ER).

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records, endoscopic examination records, endoscopic procedure records, and histological records of 667 cases from 641 patients who were followed-up for at least 12 mo, from among 1273 patients who were conformed to have gastric dysplasia after Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) of gastric mucosal lesions between January 2007 and August 2013 at the Chungnam National University Hospital.

The mean follow-up period was 33.8 mo, and the median follow-up period was 29 mo (range: 12-87). During the follow-up period, the occurrence of metachronous GAC was 4.0% (27/667). The mean and median interval periods between the occurrence of metachronous GAC and endoscopic treatment of gastric dysplasia were 36.3 and 34 mo, respectively (range: 16-71). The factors related to metachronous GAC occurrence after ER for gastric dysplasia were male sex (5.3% vs 1.0%), open-type atrophic gastritis (9.5% vs 3.4%), intestinal metaplasia (6.8% vs 2.4%), and high-grade dysplasia (HGD; 8.4% vs 3.2%). Among them, male sex [OR: 5.05 (1.18-21.68), P = 0.029], intestinal metaplasia [OR: 2.78 (1.24-6.23), P = 0.013], and HGD [OR: 2.70 (1.16-6.26), P = 0.021] were independent related factors in multivariate analysis. Furthermore, 24 of 27 GAC cases (88.9%) occurred at sites other than the previous resection sites, and 3 (11.1%) occurred at the same site as the previous resection site.

Male sex, intestinal metaplasia, and HGD were significantly related to the occurrence of metachronous GAC after ER of gastric dysplasia, and most GACs occurred at sites other than the previous resection sites.

Core tip: Gastric dysplasia is considered a premalignant lesion that can become malignant. Thus, endoscopic resection is preferred not only for the removal of these lesions but also for exact diagnosis. In our study, we investigated the relationship between the occurrence of synchronous and metachronous lesions after endoscopic treatment of gastric dysplasia and various clinical factors during the follow-up period. The incidence rates of synchronous and metachronous neoplasms after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia were 12.1% and 13.8%, respectively. In the multivariate analysis, age of < 60 years and intestinal metaplasia were independent risk factors of synchronous neoplasm. For metachronous neoplasm, especially metachronous gastric adenocarcinoma, independent risk factors were male sex, intestinal metaplasia, and high-grade dysplasia.

- Citation: Moon HS, Yun GY, Kim JS, Eun HS, Kang SH, Sung JK, Jeong HY, Song KS. Risk factors for metachronous gastric carcinoma development after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia: Retrospective, single-center study. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(24): 4407-4415

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i24/4407.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4407

Although the natural history of gastric dysplasia remains unclear, it is considered a premalignant lesion that can become malignant. Because specimens obtained by endoscopic biopsy are not representative of the entire lesion and many reports have shown histological discrepancies between such specimens and resected ones, endoscopic resection (ER) is preferred not only for the removal of these lesions but also for their exact diagnosis. Because gastric dysplasia can become malignant and poses the risk of metachronous gastric cancer, surveillance after ER is critical. Many studies have reported the short- and long-term outcomes of ER for early gastric cancer (EGC). However, the long-term results after endoscopic removal of gastric dysplasia are unclear. Therefore, we investigate the long-term outcomes and their related factors for the occurrence of gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC) after ER of gastric dysplasia.

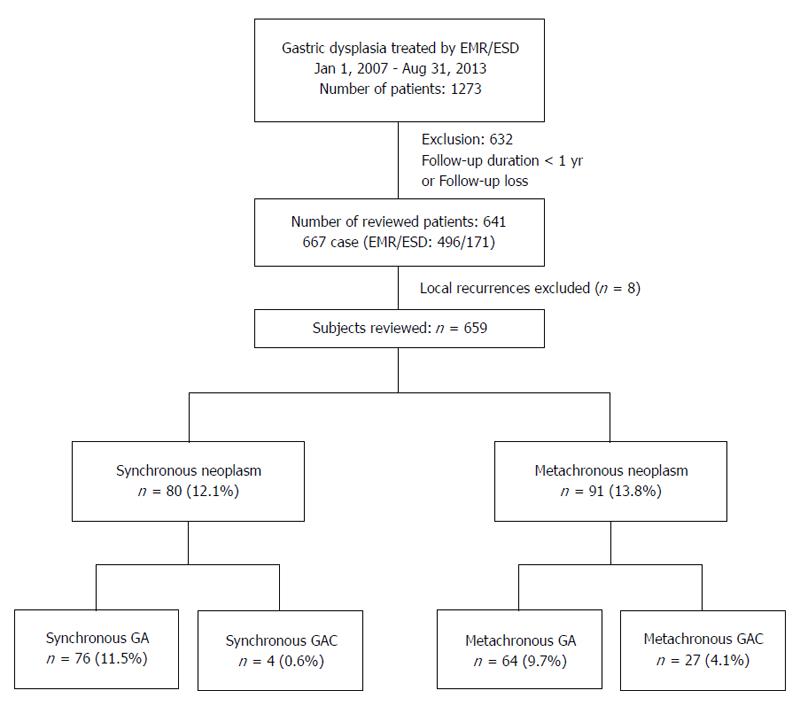

This study initially included 1273 patients who were conformed to have gastric dysplasia after endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) of gastric mucosal lesions between January 2007 and August 2013 at the Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, South Korea. Of these, 641 patients who were followed-up for at least 12 mo after endoscopic treatment were evaluated (Figure 1).

The patients’ medical records, endoscopic examination/treatment records, and histological examination results were retrospectively analyzed. The first follow-up endoscopic examination was performed between 2 and 6 mo after the endoscopic procedure. If no specific visual or pathologic abnormal lesion was observed, yearly follow-up endoscopy was performed thereafter. The occurrence rate of GAC and related factors during the follow-up period were analyzed. The lesion site was classified by dividing the gastric long axis into three sections: upper (cardia and fundus), middle (body and angle), and lower (antrum and prepylorus). The lesion size was defined as the maximum diameter of the lesion. The morphology was divided into three gross types: elevated, flat, and depressed. Cases that showed both low- and high-grade dysplasia (LGD and HGD, respectively) were classified as HGD. To determine the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection status, two biopsy-based tests (a histology test and a rapid urease test) and a 13C urea breath test were performed to determine the H. pylori infection status. Giemsa staining was used for a histological evaluation of H. pylori infection. Two specimens from the lesser curvature of the antrum and body were used in the rapid urease test (CLOtest®; Delta West, Bentley, Australia). A positive result from any of these three tests was indicative of H. pylori infection.

The gastric dysplasia grade was classified according to the Vienna classification by one specialized gastrointestinal pathologist (KS Song)[1]. We defined GAC or gastric dysplasia detected within 12 mo after ER for gastric dysplasia as synchronous lesions, and we considered mucosal lesions detected at least 12 mo after endoscopic treatment as metachronous lesions. The meaningful severity of gastric atrophy was defined as open-type atrophic gastritis by the Kimura-Takemoto classification, and the presence of intestinal metaplasia (IM) was evaluated by endoscopic examination[2,3]. Three experienced endoscopists (HS Moon, JK Sung, and HY Jeong) performed all the procedures, and all data were saved as images. The records of all the patients were reviewed retrospectively, and the severity of gastric atrophy and presence of IM in each patient was decided after discussion among the three experts.

Each categorical variable was analyzed using χ2 tests. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States); P-values were two-sided, and P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Univariate analysis was performed using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests. Multivariate analysis was performed using all variables. The risk factors for synchronous, metachronous, and cancerous lesions were examined by multivariate analysis using the logistic regression model. The incidence of metachronous gastric lesions was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

The baseline characteristics of 641 patients are shown in Table 1. The ratio of males to females was 2.4:1. The mean age of the patients was 63.5 ± 9.7 years. Most of the initial lesions were located in the lower one-third of the stomach (63.9%), and 34.2% and 1.9% were located in the middle and upper thirds, respectively. Of all lesions, 69% and 31% were smaller and larger than 30 mm in size, respectively. LGD accounted for 84% of initial confirmed lesions and HGD, for the remaining 16%. Among the patients, 570 (88.9%) and 239 (37.3%) had open-type atrophic gastritis and presence of intestinal metaplasia in the background mucosa as found endoscopically, respectively.

| Patient | n (%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 454 (70.8) |

| Female | 187 (29.2) |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 31–88 (63.5 ± 9.7) |

| < 60 | 207 (32.3) |

| ≥ 60 | 434 (67.7) |

| Number of resected lesions | |

| Single | 618 (96.4) |

| Double | 20 (3.1) |

| Triple | 3 (0.5) |

| Atrophic gastritis | |

| Closed | 570 (88.9) |

| Open | 71 (11.1) |

| Intestinal metaplasia | |

| Absence | 402 (62.7) |

| Presence | 239 (37.3) |

| Site of initial lesion | |

| Upper | 12 (1.9) |

| Mid | 219 (34.2) |

| Lower | 410 (63.9) |

| Size of initial lesion, cm | |

| < 3.0 | 442 (69.0) |

| ≥ 3.0 | 199 (31.0) |

| Morphology of initial lesion | |

| Elevated | 431 (67.3) |

| Flat | 131 (20.4) |

| Depressed | 79 (12.3) |

| Dysplasia grade of initial lesion | |

| Low | 538 (84.0) |

| High | 103 (16.0) |

| Helicobacter Pylori infection | |

| Positive | 500 (78) |

| Negative | 141 (22) |

Among the 667 cases of the 641 patients followed-up for at least 12 mo, eight lesions were local recurrences, and these were excluded from the analysis of synchronous and metachronous lesion (Figure 1). EMR and ESD were performed for 496 (74%) and 171 (26%) lesions, respectively. The overall complete resection rate was 92.3%, and it was higher in ESD cases (96.5%) than in EMR ones (90.9%). Male gender, open-type atrophic gastritis, and intestinal metaplasia were significantly different among the three groups; however, other factors were not statistically different in the baseline analysis of gastric dysplasia patients (Table 2).

| Control group | Synchronous group | Metachronous group | P value | |

| (n = 488) | (n = 80) | (n = 91) | ||

| Male gender | 328 (67.2) | 61 (76.2) | 76 (83.5) | 0.003 |

| mean ± SD, yr | 64.03 ± 9.86) | 61.66 ± 8.18 | 62.73 ± 9.96 | 0.131 |

| Dysplasia | 0.121 | |||

| Low grade | 417 (85.5) | 66 (82.5) | 70 (76.9) | |

| High grade | 71 (14.5) | 14 (17.5) | 21 (23.1) | |

| En bloc resection | 179 (36.7) | 29 (36.2) | 32 (35.2) | 0.973 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 155 (31.8) | 42 (52.5) | 45 (49.5) | 0.000 |

| Atrophy | 0.013 | |||

| Closed | 445 (91.2) | 67 (83.8) | 75 (82.4) | |

| Open | 43 (8.8) | 13 (16.2) | 16 (17.6) | |

| Resection method | 0.439 | |||

| EMR | 359 (73.6) | 64 (80.0) | 66 (72.5) | |

| ESD | 129 (26.4) | 16 (20.0) | 25 (27.5) | |

| Endoscopic findings | 0.483 | |||

| Elevated | 326 (66.8) | 54 (67.5) | 64 (70.3) | |

| Flat | 96 (19.7) | 20 (25.0) | 18 (19.8) | |

| Depressed | 66 (13.5) | 6 (7.5) | 9 (9.9) | |

| Location | 0.144 | |||

| Lower | 324 (66.4) | 46 (57.5) | 52 (57.1) | |

| Mid | 156 (32.0) | 31 (38.8) | 38 (41.8) | |

| Upper | 8 (1.6) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.1) | |

| mean ± SD, cm | 2.12 ± 0.79 | 2.53 ± 1.10 | 2.68 ±1.31 | 0.065 |

| Helicobacter Pylori infection | 385 (78.9) | 67 (83.8) | 66 (72.5) | 0.208 |

A total of 80 cases were defined as synchronous lesions. In multivariate analysis, age above 60 years (OR = 0.395, 95%CI: 0.241-0.646, P value = 0.000) and presence of IM (OR = 2.260, 95%CI: 1.377-3.707, P value = 0.001) showed statistically significant differences. The other groups did not show statistically significant differences when the rates were compared according to the location, size, or morphology of the lesions (Table 3).

| Control group | Synchronous group | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| (n = 488) | (n = 80) | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | 0.120 | |||||

| Male | 328 (67.2) | 61 (76.2) | ||||

| Female | 160 (32.8) | 19 (23.8) | ||||

| Age | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 343 (70.3) | 40 (50.0) | 0.395 | 0.241-0.646 | ||

| < 60 | 145 (29.7) | 40 (50.0) | 1.000 | |||

| Dysplasia | 0.500 | |||||

| Low grade | 417 (85.5) | 66 (82.5) | ||||

| High grade | 71 (14.5) | 14 (17.5) | ||||

| En bloc resection | 179 (37.7) | 29 (36.2) | 0.941 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 155 (31.8) | 42 (52.5) | 0.001 | 2.260 | 1.377-3.707 | 0.001 |

| Atrophy | 0.044 | 0.086 | ||||

| Closed | 445 (91.2) | 67 (83.8) | 1.000 | |||

| Open | 43 (8.8) | 13 (16.2) | 1.860 | 0.915-3.783 | ||

| Resection method | 0.269 | |||||

| EMR | 359 (73.6) | 64 (80.0) | ||||

| ESD | 129 (26.4) | 16 (20.0) | ||||

| Endoscopic findings | 0.231 | |||||

| Elevated | 326 (66.8) | 54 (67.5) | ||||

| Flat | 96 (19.7) | 20 (25.0) | ||||

| Depressed | 66 (13.5) | 6 (7.5) | ||||

| Location | 0.185 | |||||

| Lower | 324 (66.4) | 46 (57.5) | ||||

| Mid | 156 (32.0) | 31 (38.8) | ||||

| Upper | 8 (1.6) | 3 (3.8) | ||||

| Size | 0.295 | |||||

| ≤ 3 | 334 (68.4) | 60 (75.0) | ||||

| > 3 | 154 (31.6) | 20 (25.0) | ||||

| Helicobacter Pylori infection | 385 (78.9) | 67 (83.8) | 0.371 | |||

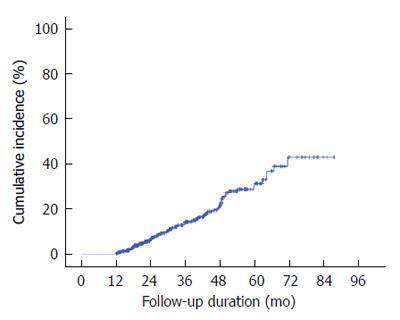

During the follow-up period, eight lesions recurred in the ER scar area, and these were excluded. A total of 91 lesions were finally classified as metachronous ones. Of these, 27 were pathologically diagnosed as adenocarcinoma and 64, as gastric dysplasia. In multivariate analysis, male gender (OR = 2.314, 95%CI: 1.281-4.179, P value = 0.005) and presence of IM (OR = 1.915; 95%CI: 1.203-3.04, P value = 0.006) showed statistically significant differences for metachronous lesions (Table 4). The median interval between the diagnosis of gastric dysplasia and that of the first metachronous lesion was 29.5 mo (range: 18-43 mo). The annual incidence rate of metachronous lesions per 1000 person-years was 1.26% and the cumulative 5-year incidence metachronous neoplasm after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia was 31% (Figure 2).

| Control group | Metachronous group | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| (n = 488) | (n = 91) | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | 0.002 | 0.005 | ||||

| Male | 328 (67.2) | 76 (83.5) | 2.314 | 1.281-4.179 | ||

| Female | 160 (32.8) | 15 (16.5) | 1.000 | |||

| Age | 0.174 | |||||

| ≥ 60 | 343 (70.3) | 70 (76.9) | ||||

| < 60 | 145 (29.7) | 21 (23.1) | ||||

| Dysplasia | 0.059 | |||||

| Low grade | 417 (85.5) | 70 (76.9) | ||||

| High grade | 71 (14.5) | 21 (23.1) | ||||

| En bloc resection | 179 (37.7) | 32 (35.2) | 0.813 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 155 (31.8) | 45 (49.5) | 0.002 | 1.915 | 1.203-3.049 | 0.006 |

| Atrophy | 0.022 | 0.103 | ||||

| Closed | 445 (91.2) | 75 (82.4) | 1.000 | |||

| Open | 43 (8.8) | 16 (17.6) | 1.708 | 0.897-3.252 | ||

| Resection method | 0.897 | |||||

| EMR | 359 (73.6) | 66 (72.5) | ||||

| ESD | 129 (26.4) | 25 (27.5) | ||||

| Endoscopic findings | 0.665 | |||||

| Elevated | 326 (66.8) | 64 (70.3) | ||||

| Flat | 96 (19.7) | 18 (19.8) | ||||

| Depressed | 66 (13.5) | 9 (9.9) | ||||

| Location | 0.172 | |||||

| Lower | 324 (66.4) | 52 (57.1) | ||||

| Mid | 156 (32.0) | 38 (41.8) | ||||

| Upper | 8 (1.6) | 1 (1.1) | ||||

| Size | 0.394 | |||||

| ≤ 3 | 334 (68.4) | 58 (63.7) | ||||

| > 3 | 154 (31.6) | 33 (36.3) | ||||

| Helicobacter Pylori infection | 385 (78.9) | 66 (72.5) | 0.210 | |||

During the follow-up period, 27 additional cases were detected within 12 mo after ER. These were considered missed synchronous lesions. Furthermore, 64 cases (9.8%) were detected after 12 mo. The mean period and median period from ER to detection of metachronous adenoma were 31.4 and 27 mo (range: 13-66 mo), respectively. In multivariate analysis, male gender (OR = 1.868, 95%CI: 0.985-3.543, P value = 0.056), IM (OR = 1.619, 95%CI: 0.947-2.767, P value = 0.078), and open-type atrophic gastritis (OR = 1.295, 95%CI: 0.589-2.846, P value = 0.520) did not show statistically significant differences for metachronous gastric dysplasia.

In total, 31 lesions in 641 patients were pathologically diagnosed as GAC during the follow-up period. Of these, 4 and 27 were synchronous and metachronous gastric cancer, respectively. The degree of differentiation of metachronous gastric cancer was as follows: moderately differentiated cancer in 20 patients, well-differentiated cancer in 5 patients, and poorly differentiated cancer in 2 patients The median period from ER to detection of metachronous cancer was 34 mo (range: 16-71 mo). The occurrence rate of GAC was higher in males (5.3%) than in females (1.0%), and this difference was statistically significant (OR = 5.238, 95%CI: 1.211-22.661, P value = 0.027). There was no statistically significant difference between age above (4.0%) and below (4.1%) 60 years or when the rates were compared according to the location, size, or morphology of lesions. Group who had HGD or included an HGD component had higher GAC occurrence rate (8.4% vs 3.2%) and showed a statistically significant difference (OR = 2.741, 95%CI: 1.148-6.546, P value = 0.023). When there was intestinal metaplasia in background mucosa, there was a statistically significant difference in the GAC occurrence rates (OR = 2.647, 95%CI: 1.165-6.012, P value = 0.020). Cases with open-type atrophic gastritis showed higher GAC occurrence rate than others (9.5% vs 3.4%, P value = 0.022) in univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis (P value = 0.188). There was small difference in occurrence rates between en bloc resection and piecemeal resection (3.7% vs 4.2%, P = 0.840). There was no statistically significant difference between EMR and ESD and between complete and incomplete resection (Table 5).

| Control group(n = 488) | Metachronous carcinoma group (n = 27) | Univariate analysisP value | Multivariate analysis | |||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | ||||

| Sex | 0.005 | 0.027 | ||||

| Male | 328 (67.2) | 25 (92.6) | 5.238 | 1.211-22.661 | ||

| Female | 160 (32.8) | 2 (7.4) | 1.000 | |||

| Age | 0.671 | |||||

| ≥ 60 | 343 (70.3) | 18 (66.7) | ||||

| < 60 | 145 (29.7) | 9 (33.3) | ||||

| Dysplasia | 0.024 | 0.023 | ||||

| Low grade | 417 (85.5) | 18 (66.7) | 1.000 | |||

| High grade | 71 (14.5) | 9 (33.3) | 2.741 | 1.148-6.546 | ||

| En bloc resection | 179 (37.7) | 9 (33.3) | 0.839 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 155 (31.8) | 9 (33.3) | 0.005 | 2.647 | 1.165-6.012 | 0.020 |

| Atrophy | 0.010 | 0.065 | ||||

| Closed | 445 (91.2) | 20 (74.1) | 1.000 | |||

| Open | 43 (8.8) | 7 (25.9) | 2.492 | 0.946-6.569 | ||

| Resection method | 0.503 | |||||

| EMR | 359 (73.6) | 18 (66.7) | ||||

| ESD | 129 (26.4) | 9 (33.3) | ||||

| Endoscopic findings | 0.546 | |||||

| Elevated | 326 (66.8) | 21 (77.8) | ||||

| Flat | 96 (19.7) | 3 (11.1) | ||||

| Depressed | 66 (13.5) | 3 (11.1) | ||||

| Location | 1.000 | |||||

| Lower | 324 (66.4) | 17 (63.0) | ||||

| Mid | 156 (32.0) | 9 (33.3) | ||||

| Upper | 8 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Size | 0.532 | |||||

| ≤ 3 | 334 (68.4) | 17 (63.0) | ||||

| > 3 | 154 (31.6) | 10 (37.0) | ||||

| Helicobacter Pylori infection | 385 (78.9) | 20 (74.1) | 0.629 | |||

A few studies have focused on the incidence of metachronous and synchronous lesions in patients with gastric dysplasia after ER. In a previous study, the metachronous and synchronous gastric cancer rate among patients with EGC treated by ER was reported to range from 2.7% to 14%[4-8] and 1.2% to 19.2%[5,8-10], respectively. With recent advancements in ER for gastric lesions, most of the stomach is preserved, and the risk of developing metachronous or synchronous lesions at other sites of the remnant gastric mucosa has become a major problem. One retrospective study showed an overall incidence of 20.1% (30/149) for metachronous lesions in patients with gastric dysplasia after ER during a median period of 37.3 mo. Among these, the incidence of gastric carcinoma and dysplasia was 5.4% (8/149) and 14.8% (22/149), respectively. In addition, the incidence of synchronous lesion was 20.8% (31/149)[11]. In our study of 659 cases of 641 patients with confirmed gastric dysplasia after ER, the incidence of metachronous lesions was 13.8% (91/656) during a median follow-up period of 29 mo; among these, the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer and gastric dysplasia was 4.1% (27/656) and 9.7% (64/656), respectively. In addition, the incidence of synchronous lesions was 12.1% (80/656), most of which were gastric dysplasia.

Various predictive factors of metachronous lesion after ER have been reported for patients with EGC, including synchronous multiplicity of gastric cancer[6], old age[6,10,12], antrum atrophy[10], undifferentiated histology[13] and upper location[13], and H. pylori infection[14-17]. However, unlike our study, in which the focus was on gastric dysplasia, most other studies on risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of the gastric lesion included patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Thus, this study was designed to elucidate the independent risk factors of metachronous gastric cancer after the endoscopic removal of gastric dysplasia with a large volume. In this study, male gender, IM, and HGD were found to be independent risk factors of the development of metachronous gastric cancer after ER of gastric dysplasia.

IM is an established precancerous condition as they constitute a background for dysplasia and intestinal-type gastric cancer. According to a cohort study from China that enrolled 3306 subjects with a follow-up of 4-5 years, the OR for the progression from intestinal metaplasia to gastric cancer was 17-29[18]. In addition, another prospective study from Japan reported that individuals with IM had at least a six-fold increase in the risk of gastric cancer[19]. However, studies that addressed the relationship between IM and metachronous lesion after ER of gastric neoplasia are scarce. Our results are consistent with those of an earlier study[20] that reported that IM was an independent risk factor of metachronous gastric neoplasia, although our study classified IM as simply positive and negative. In our study, IM was evaluated by using endoscopic examination. So the assessment of the severity of IM has some limitation. Therefore, further studies are necessary to elucidate the relationship of IM severity and the development of a metachronous lesion after ER of gastric neoplasm.

HGD is well known to be at high risk of progression to gastric cancer. The rate of malignant transformation of HGD has been reported to range from 60% to 85% over a median interval of 4 to 48 mo[21]. A recent nationwide cohort study demonstrated that HGD was associated with a 40-fold increased risk of progression to gastric cancer and that 25% of patients with HGD were diagnosed as having gastric cancer within 12 mo of follow-up[22]. Recently, one study demonstrated that the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer after ER of gastric dysplasia was similar to that after ER of EGC[23]. As only few studies have evaluated the risk factors of metachronous lesion after ER of gastric dysplasia, the association between HGD and metachronous cancer is elusive. However, considering the above mentioned results, that is, the risk of malignant change and the similar risk of metachronous gastric cancer occurrence, HGD can be a risk factors of metachronous gastric cancer after ER of gastric dysplasia.

Male gender was also found to be a predictive factor of metachronous cancer. This result is similar to that of a previous study that suggested that male patients more frequently developed metachronous gastric cancer after surgery or ER[8,9,24]. The dominant proportion of men in our enrolled patients may have affected this result.

Some studies reported that H. pylori infection was associated with metachronous tumor development after ER of gastric neoplasms. One retrospective study that enrolled 184 patients with HGD and 787 patients with EGC demonstrated that H. pylori infection was the only independent risk factor of metachronous tumor[14]. The difference in the mean follow-up duration (37 mo) and enrolled patients (HGD and EGC) may have influenced these results. Some studies documented that H. pylori eradication can prevent the development of metachronous lesion after ER of gastric dysplasia[15,25,26]. In a retrospective study of 1872 patients with gastric dysplasia who underwent ER, the cumulative incidence of metachronous tumor was significantly lower in the H. pylori-eradicated group than in the H. pylori-persistent group[25]. Unlike this study, our study did not focus on whether H. pylori eradication can prevent the development of metachronous tumor after ER. The effect of H. pylori eradication on the progression of gastric dysplasia is uncertain so far. However, H. pylori eradication may decrease the incidence of metachronous lesions. Currently some guideline recommend H. pylori eradication for patients with previous dysplasia after ER[27,28].

Optimal surveillance strategies, including the follow-up period and interval after ER of gastric dysplasia, have not yet been established. and no population with high risk of developing metachronous neoplasms has been identified. Previous studies of early gastric cancer after ER have shown that the median interval between primary ER and diagnosis of metachronous lesion was 30-36 mo[7,10,12]. In this study, surveillance esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed at least once a year after ER of gastric dysplasia. The median time to development of metachronous tumors was 29 mo (range, 12-71 mo). In our study, aggressive carcinoma was not detected within follow-up period, and all diagnosed metachronous gastric cancers were resected endoscopically. Based on these findings, we recommend that yearly surveillance after ER of gastric dysplasia is adequate for high-risk patient groups (male patients and those with high-grade dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia). Meticulous endoscopic follow-up after ER in patients with gastric dysplasia can result in early diagnosis of gastric cancer.

This study has some limitations. First, it was a single-center, retrospective study. Second, the severity of atrophy and presence of IM were graded based on endoscopic findings instead of pathological results. Third, the number of patients enrolled in this study was relatively small, and the follow-up duration was relatively short. Finally, about half of the patients were not followed up, and the occurrence rates of synchronous and metachronous lesions could be underestimated.

In conclusion, this study showed that the incidence rates of synchronous and metachronous neoplasms after ER of gastric dysplasia were 12.1% and 13.8%, respectively. Of these cases, 4.1% are metachronous GAC. The median detection period of metachronous gastric cancer after ER was 31 mo. Male gender, IM, and HGD were independent risk factors of metachronous GAC after ER of gastric dysplasia. Therefore, careful endoscopic surveillance should be performed in patients with IM and HGD after ER of gastric dysplasia.

Gastric dysplasia is known as a neoplastic lesion and precursor of gastric adenocarcinoma. Although the natural course of gastric dysplasia is unclear, considerable evidence suggests that patients with gastric dysplasia are at increased risk of gastric cancer. Therefore, endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection is routinely performed for resection of the premalignant lesion. After resection of gastric dysplasia, gastric adenocarcinoma can be detected during the follow-up period. However, few studies have been conducted regarding factors related to the development of gastric cancer. Therefore, they evaluated the results during follow-up in patients who had been confirmed as having gastric dysplasia after endoscopic resection.

Studies regarding long-term results of endoscopic removal of gastric dysplasia are scarce. Many studies have reported the short- and long-term outcomes of endoscopic treatment for early gastric cancer. The results of this study contribute to clarifying long-term outcomes and the factors related to the development of gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC) after endoscopic resection (ER) of gastric dysplasia.

In this study, the incidences of synchronous and metachronous neoplasms after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia were 12.1% and 13.8%, respectively; in particular, that of metachronous GAC was 4.1%, and male gender, intestinal metaplasia, and high-grade dysplasia were independent risk factors of metachronous GAC. This emphasizes that careful endoscopic surveillance should be performed after ER of gastric dysplasia.

This study suggests that yearly and meticulous endoscopic surveillance after ER of gastric dysplasia is adequate for high-risk patients (male patients and those with the presence of high-grade dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia).

Dysplasia: With reference to the gastrointestinal system, defined as the presence of histologically unequivocal neoplastic epithelium without evidence of tissue invasion. Synchronous: Defined as secondary gastric neoplasms found in another site and within 1 year of endoscopic treatment. Metachronous: Defined as new gastric neoplasms occurring in different areas from that of the initial lesion at least 1 year after ER.

The author of this paper evaluated the incidence and related risk factors of synchronous and metachronous neoplasms after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia. Male gender, underlying intestinal metaplasia, and histopathologically confirmed high-grade dysplasia after endoscopic resection were independent risk factors of metachronous gastric cancer; and further clinical trials in a large population of gastric dysplasia patients will be valuable.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fiori E, Tseng PH S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Stolte M. The new Vienna classification of epithelial neoplasia of the gastrointestinal tract: advantages and disadvantages. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kimura K, Takemoto T. An Endoscopic Recognition of the Atrophic Border and its Significance in Chronic Gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;1:87-97. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 742] [Article Influence: 43.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Fukuta N, Ida K, Kato T, Uedo N, Ando T, Watanabe H, Shimbo T. Endoscopic diagnosis of gastric intestinal metaplasia: a prospective multicenter study. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:526-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim JJ, Lee JH, Jung HY, Lee GH, Cho JY, Ryu CB, Chun HJ, Park JJ, Lee WS, Kim HS. EMR for early gastric cancer in Korea: a multicenter retrospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:693-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nasu J, Doi T, Endo H, Nishina T, Hirasaki S, Hyodo I. Characteristics of metachronous multiple early gastric cancers after endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2005;37:990-993. |

| 6. | Arima N, Adachi K, Katsube T, Amano K, Ishihara S, Watanabe M, Kinoshita Y. Predictive factors for metachronous recurrence of early gastric cancer after endoscopic treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:44-47. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Nakajima T, Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Yokoi C, Saito D. Metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection: how effective is annual endoscopic surveillance? Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:93-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kato M, Nishida T, Yamamoto K, Hayashi S, Kitamura S, Yabuta T, Yoshio T, Nakamura T, Komori M, Kawai N. Scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: a multicentre retrospective cohort study by Osaka University ESD study group. Gut. 2013;62:1425-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kobayashi M, Narisawa R, Sato Y, Takeuchi M, Aoyagi Y. Self-limiting risk of metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:169-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Han JS, Jang JS, Choi SR, Kwon HC, Kim MC, Jeong JS, Kim SJ, Sohn YJ, Lee EJ. A study of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1099-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baek DH, Kim GH, Park DY, Lee BE, Jeon HK, Lim W, Song GA. Gastric epithelial dysplasia: characteristics and long-term follow-up results after endoscopic resection according to morphological categorization. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jang MY, Cho JW, Oh WG, Ko SJ, Han SH, Baek HK, Lee YJ, Kim JW, Jung GM, Cho YK. Clinicopathological characteristics of synchronous and metachronous gastric neoplasms after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Korean J Int Med. 2013;28:687-693. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Seo JH, Park JC, Kim YJ, Shin SK, Lee YC, Lee SK. Undifferentiated histology after endoscopic resection may predict synchronous and metachronous occurrence of early gastric cancer. Digestion. 2010;81:35-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lim JH, Kim SG, Choi J, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Risk factors for synchronous or metachronous tumor development after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasms. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:817-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bae SE, Jung HY, Kang J, Park YS, Baek S, Jung JH, Choi JY, Kim MY, Ahn JY, Choi KS. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:60-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim YI, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Ryu KW, Kim YW. The association between Helicobacter pylori status and incidence of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2014;19:194-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bang CS, Baik GH, Shin IS, Kim JB, Suk KT, Yoon JH, Kim YS, Kim DJ. Helicobacter pylori Eradication for Prevention of Metachronous Recurrence after Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2015;30:749-756. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | You WC, Li JY, Blot WJ, Chang YS, Jin ML, Gail MH. Evolution of precancerous lesions in a rural Chinese population at high risk of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;83. |

| 19. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3126] [Cited by in RCA: 3183] [Article Influence: 132.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yoon H, Kim N, Shin CM, Lee HS, Kim BK, Kang GH, Kim JM, Kim JS, Lee DH, Jung HC. Risk Factors for Metachronous Gastric Neoplasms in Patients Who Underwent Endoscopic Resection of a Gastric Neoplasm. Gut Liver. 2016;10:228-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sung JK. Diagnosis and management of gastric dysplasia FAU - Sung, Jae Kyu. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31:201-209. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, Casparie MK, de Vries E, Meijer GA, Kuipers EJ, Kuipers EJ. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:945-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 585] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yoon SB, Park JM, Lim CH, Kim JS, Cho YK, Lee BI, Lee IS, Kim SW, Choi MG. Incidence of gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of gastric adenoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1176-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nozaki I, Nasu J, Kubo Y, Tanada M, Nishimura R, Kurita A. Risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer in the remnant stomach after early cancer surgery. World J Surg. 2010;34:1548-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shin SH, Jung DH, Kim JH, Chung HS, Park JC, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC. Helicobacter pylori Eradication Prevents Metachronous Gastric Neoplasms after Endoscopic Resection of Gastric Dysplasia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chon I, Choi C, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N, Lee DH. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent dysplasia development after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2013;61:307-312. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, O’Connor A, Pereira C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Correia R, Ensari A. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Endoscopy. 2012;44:74-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Evans JA, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Fisher DA, Foley K, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Lightdale JR. The role of endoscopy in the management of premalignant and malignant conditions of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |