Published online Mar 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.2012

Peer-review started: November 4, 2016

First decision: December 28, 2016

Revised: December 30, 2016

Accepted: January 4, 2017

Article in press: January 4, 2017

Published online: March 21, 2017

Processing time: 136 Days and 6.3 Hours

To evaluate the predictive value of the expression of chromosomal maintenance (CRM)1 and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)5 in gastric cancer (GC) patients after gastrectomy.

A total of 240 GC patients who received standard gastrectomy were enrolled in the study. The expression level of CRM1 and CDK5 was detected by immunohistochemistry. The correlations between CRM1 and CDK5 expression and clinicopathological factors were explored. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses were used to identify prognostic factors for GC. Receiver operating characteristic analysis was used to compare the accuracy of the prediction of clinical outcome by the parameters.

The expression of CRM1 was significantly related to size of primary tumor (P = 0.005), Borrmann type (P = 0.006), degree of differentiation (P = 0.004), depth of invasion (P = 0.008), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.013), TNM stage (P = 0.002) and distant metastasis (P = 0.015). The expression of CDK5 was significantly related to sex (P = 0.048) and Lauren’s classification (P = 0.011). Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified that CRM1 and CDK5 co-expression status was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival (OS) of patients with GC. Integration of CRM1 and CDK5 expression could provide additional prognostic value for OS compared with CRM1 or CDK5 expression alone (P = 0.001).

CRM1 and CDK5 co-expression was an independent prognostic factors for GC. Combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression could provide a prognostic model for OS of GC.

Core tip: Our study shows that low expression of chromosomal maintenance (CRM)1 and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)5 was associated with poor prognosis of gastric cancer patients. The expression of CRM1 or CDK5 influenced the prognostic value of each other. Combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression had better prognostic power than their individual expression had.

- Citation: Sun YQ, Xie JW, Xie HT, Chen PC, Zhang XL, Zheng CH, Li P, Wang JB, Lin JX, Cao LL, Huang CM, Lin Y. Expression of CRM1 and CDK5 shows high prognostic accuracy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(11): 2012-2022

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i11/2012.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.2012

Gastric cancer (GC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, although its incidence and mortality have decreased dramatically over the last 50 years[1]. In 2011 there were about 420000 new cases diagnosed (70% men and 30% women) and 300 000 deaths due to this disease in China[2-4]. Clinically, the prognostic classification model for outcomes of GC patients is mainly the TNM staging system based on the histopathological score[5], whereas the underlying molecular and cellular processes during carcinogenesis of GC are ignored. Patients with the same TNM stage may have wide variations in survival owing to different genetic mutation status[6]. Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular pathology might provide better prognostic biomarkers and guidance for more precise treatment for GC patients.

The human nuclear export protein chromosomal maintenance (CRM)1 (also known as exportin 1) has been reported to control multiple processes during cellular mitosis and is important in mediating nuclear export of cargo proteins that contain specific leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES) consensus sequences[7,8]. Previous studies have demonstrated that CRM1 is important for the functions of proteins such as epidermal growth factor receptor, p53, p27, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)5 and Akt1[9-13]. The prognostic value of CRM1 expression has been reported in many types of cancer including ovarian cancer[14], osteosarcoma[15], glioma[16], pancreatic cancer[17] and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[18]. However, whether CRM1 expression contributes to the development or progression of GC is not known.

CDK5 is a proline-directed serine/threonine kinase and participates in a variety of pathological and physiological functions[19,20]. Increasing evidence suggests a role for CDK5 in cancer tumorigenesis and progression[21,22]. Our previous work has demonstrated that in GC, CDK5 downregulation is an independent prognostic factor and the nuclear localization of CDK5 is critical for its tumor-suppressor function[23]. Given that CRM1 regulates CDK5 cytoplasm localization in neurons[12], we hypothesized that the functional correlation between CRM1 and CDK5 may affect the prognostic power of each molecule. In the present study, we examined the expression of CRM1 and CDK5 in 240 gastric tumor tissues and analyzed their correlation with patient clinicopathological features.

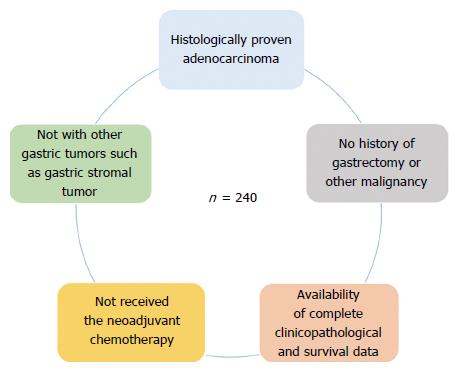

The study cohort was composed of samples from 240 patients (178 men and 62 women, mean age: 59.5 years) with gastric adenocarcinoma, who had undergone gastrectomy at the Department of Gastric Surgery, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, between January 2009 and December 2009. Following surgery, routine chemotherapy was given to patients with advanced disease and no radiation treatment was administered to any of the patients. Eligibility criteria for patients included in this study were: (1) histologically proven adenocarcinoma; (2) no other gastric tumors such as gastric stromal tumor; (3) no history of gastrectomy or other malignancy; (4) no prior neoadjuvant chemotherapy; and (5) availability of complete clinicopathological and survival data (Figure 1). The study was performed with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical Union Hospital. Written consent was given by the patients for their information and specimens to be stored in the hospital database and used for research.

The clinical and pathological data were recorded prospectively for the retrospective analysis. The clinicopathological data for the 240 GC patients included age, sex, size of primary tumor, location of primary tumor, degree of differentiation, histological type, Lauren’s classification, Borrmann type, depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, vessel invasion and distant metastasis. The pathological stage of the tumor was reassessed according to the 2010 International Union Against Cancer on GC TNM Classification (seventh edition)[5]. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from curative surgery to death or the last clinical follow-up. After surgery, all patients were followed by outpatient visits, telephone calls and letters every 3 mo in the first 2 years, every 6 mo in the next 3 years, and every year afterwards or until death. The deadline for follow-up was October 2015. All patients had follow-up records for > 5 years.

Paraffin blocks that contained sufficient formalin-fixed tumor specimens were serial sectioned at 4 μm and mounted on silane-coated slides for immunohistochemistry analysis. The sections were deparaffinized with dimethylbenzene and rehydrated through 100, 100, 95, 85, and 75% ethanol. Antigen retrieval treatment was done in 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate buffer (autoclaved at 121 °C for 2 min, pH 6.0) and endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubation in 3% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature. The sections were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and blocked with 10% goat serum (ZhongShan Biotechnology, China) for 30 min and incubated with rabbit anti-human CRM1 (ab24189, 1:200 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States) or CDK5 (sc-173, 1:150 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, United States) antibody in a humidified chamber at 4 °C overnight. Following three additional washes in PBS, the sections were incubated with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. The visualization signal was developed with diaminobenzidine solution and all slides were counterstained with 20% hematoxylin. Finally, all slides were dehydrated and mounted on coverslips. For negative controls, the primary antibody diluent was used to replace primary antibody.

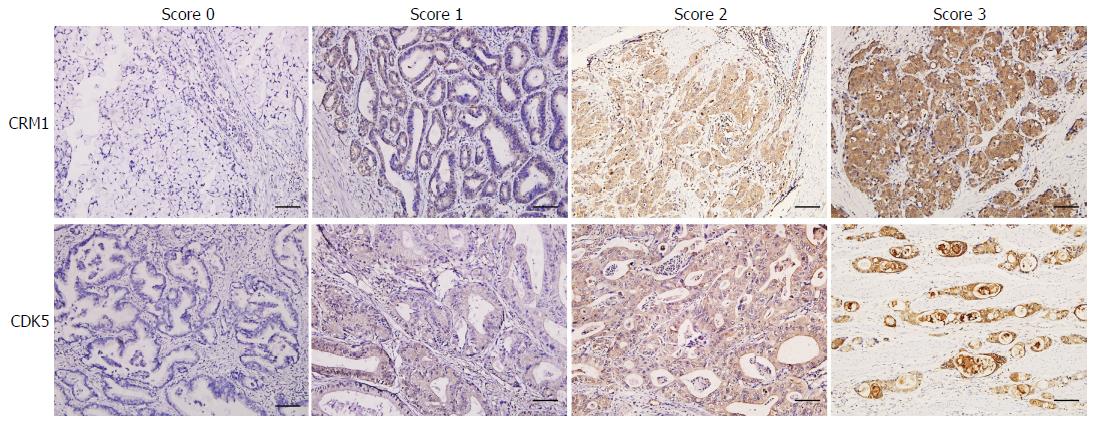

The stained tissue sections were reviewed under a microscope by two pathologists who were blinded to the clinical parameters, and scored independently according to the intensity of cellular staining and the proportion of stained tumor cells[6]. The CRM1 and CDK5 proteins were immunohistochemically stained yellowish to brown in the cytoplasm and/or nuclei of cancer cells. The expression pattern of CRM1 and CDK5 was all or none in tumor tissues, suggesting the score for the proportion of stained tumor cells was unavailable. The staining intensity was scored as 0 (no staining), 1 (weak staining, light yellow), 2 (moderate staining, yellow brown), and 3 (strong staining, brown) (Figure 2). The CRM1 and CDK5 protein expression was considered low if the score was ≤ 1 and high if it was ≥ 2.

IBM SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) was used for all statistical analyses. χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze categorical data. Univariate survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the significance of difference between groups was analyzed using the log-rank test. The stepwise Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for multivariate survival analysis, with adjustments for variables that may have been significant prognostic factors according to the univariate analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to compare the accuracy of the prediction of clinical outcome by the parameters. All P values were two-sided and statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05.

We examined CRM1 and CDK5 protein expression in tumor tissues from 240 GC patients using immunohistochemistry. The expression of CRM1 and CDK5 proteins were scored as low in 149 (62.08%) and 91 (37.92%) samples, and high in 91 (37.92%) and 149 (62.08%) samples, respectively. Based on the combined expression of CRM1 and CDK5, we classified the patients into three subtypes: CRM1 and CDK5 high (n = 63), CRM1 or CDK5 low (n = 114) and CRM1 and CDK5 low (n = 63).

The correlation between expression of CRM1 and CDK5 and the clinicopathological features were analyzed (Table 1). CRM1 expression was significantly related to size of primary tumor (P = 0.005), Borrmann type (P = 0.006), degree of differentiation (P = 0.004), depth of invasion (P = 0.008), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.013), TNM stage (P = 0.002) and distant metastasis (P = 0.015). The expression of CDK5 was significantly related to sex (P = 0.048) and Lauren’s classification (P = 0.011). The correlation between combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression and the clinicopathological features was also analyzed. The combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression was significantly related to size of primary tumor (P = 0.026), degree of differentiation (P = 0.007), Lauren’s classification (P = 0.019), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.015), TNM stage (P = 0.035) and vessel invasion (P = 0.021) (Table 2).

| Variables | Total | CRM1 expression | CDK5 expression | ||||||

| Low (n = 149) | High (n = 91) | χ2 | P value | Low (n = 91) | High (n = 149) | χ2 | P value | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 178 | 110 | 68 | 0.024 | 0.877 | 61 | 117 | 3.893 | 0.0481 |

| Female | 62 | 39 | 23 | 30 | 32 | ||||

| Age at surgery (yr) | |||||||||

| ≤ 60 | 120 | 78 | 42 | 0.867 | 0.352 | 46 | 74 | 0.018 | 0.894 |

| > 60 | 120 | 71 | 49 | 45 | 75 | ||||

| Size of primary tumor (cm) | |||||||||

| ≤ 5 | 99 | 51 | 48 | 7.995 | 0.0051 | 35 | 64 | 0.470 | 0.493 |

| > 5 | 141 | 98 | 43 | 56 | 85 | ||||

| Location of primary tumor | |||||||||

| Upper 1/3 | 56 | 33 | 23 | 5.290 | 0.152 | 22 | 34 | 1.718 | 0.633 |

| Middle 1/3 | 59 | 39 | 20 | 21 | 38 | ||||

| Lower 1/3 | 103 | 59 | 44 | 37 | 66 | ||||

| More than 1/3 | 22 | 18 | 4 | 11 | 11 | ||||

| Borrmann type | |||||||||

| Early stage | 10 | 4 | 6 | 10.118 | 0.0061 | 5 | 5 | 0.774 | 0.679 |

| I + II type | 89 | 46 | 43 | 32 | 57 | ||||

| III + IV type | 141 | 99 | 42 | 54 | 87 | ||||

| Degree of differentiation | |||||||||

| Well/moderate | 96 | 49 | 47 | 8.287 | 0.0041 | 30 | 66 | 3.021 | 0.082 |

| Poor and not | 144 | 100 | 44 | 61 | 83 | ||||

| Lauren’s classification | |||||||||

| Intestinal type | 46 | 33 | 13 | 2.254 | 0.176 | 25 | 21 | 6.527 | 0.0111 |

| Diffuse type | 294 | 116 | 78 | 66 | 128 | ||||

| Histological type | |||||||||

| Papillary | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2.958 | 0.398 | 3 | 4 | 7.052 | 0.070 |

| Tubular | 187 | 112 | 75 | 63 | 124 | ||||

| Mucinous | 20 | 13 | 7 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| Signet-ring cell | 26 | 20 | 6 | 15 | 11 | ||||

| Depth of invasion | |||||||||

| T1 | 40 | 18 | 22 | 11.908 | 0.0081 | 15 | 25 | 2.145 | 0.543 |

| T2 | 27 | 13 | 14 | 8 | 19 | ||||

| T3 | 62 | 38 | 24 | 21 | 41 | ||||

| T4 | 111 | 80 | 31 | 47 | 64 | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||||||

| N0 | 63 | 29 | 34 | 10.781 | 0.0131 | 23 | 40 | 4.868 | 0.182 |

| N1 | 40 | 29 | 11 | 11 | 29 | ||||

| N2 | 43 | 26 | 17 | 14 | 29 | ||||

| N3 | 94 | 65 | 29 | 43 | 51 | ||||

| TNM stage | |||||||||

| I | 44 | 18 | 26 | 15.074 | 0.0021 | 15 | 29 | 1.058 | 0.787 |

| II | 55 | 33 | 22 | 19 | 36 | ||||

| III | 123 | 82 | 41 | 49 | 74 | ||||

| IV | 18 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 10 | ||||

| Vessel invasion | |||||||||

| Negative | 230 | 141 | 89 | 1.423 | 0.233 | 88 | 142 | 0.278 | 0.598 |

| Positive | 10 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 7 | ||||

| Distant metastasis | |||||||||

| Negative | 222 | 133 | 89 | 5.940 | 0.0151 | 83 | 139 | 0.352 | 0.553 |

| Positive | 18 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 10 | ||||

| Variables | Total | CRM1 and CDK5 High expression | CRM1 or CDK5 Low expression | CRM1 and CDK5 Low expression | χ2 | P value |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 178 | 42 | 87 | 49 | 2.553 | 0.279 |

| Female | 62 | 21 | 27 | 14 | ||

| Age at surgery(yr) | ||||||

| ≤ 60 | 120 | 35 | 54 | 31 | 1.109 | 0.574 |

| > 60 | 120 | 28 | 60 | 32 | ||

| Size of primary tumor (cm) | ||||||

| ≤ 5 | 99 | 22 | 42 | 35 | 7.275 | 0.0261 |

| > 5 | 141 | 41 | 72 | 28 | ||

| Location of primary tumor | ||||||

| Lower 1/3 | 56 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 10.848 | 0.093 |

| Middle 1/3 | 59 | 14 | 32 | 13 | ||

| Upper 1/3 | 103 | 22 | 52 | 29 | ||

| More than 1/3 | 22 | 9 | 11 | 2 | ||

| Borrmann type | ||||||

| Early stage | 10 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 6.035 | 0.197 |

| I + II type | 89 | 20 | 38 | 31 | ||

| III + IV type | 141 | 41 | 71 | 29 | ||

| Degree of differentiation | ||||||

| Well/moderate | 96 | 18 | 43 | 35 | 10.027 | 0.0071 |

| Poor and not | 144 | 45 | 71 | 28 | ||

| Lauren’s classification | ||||||

| Intestinal type | 46 | 17 | 24 | 5 | 7.875 | 0.0191 |

| Diffuse type | 194 | 46 | 90 | 58 | ||

| Histological type | ||||||

| Papillary | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 11.127 | 0.850 |

| Tubular | 187 | 44 | 87 | 56 | ||

| Mucinous | 20 | 5 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Signet-ring cell | 26 | 12 | 11 | 3 | ||

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| T1 | 40 | 8 | 17 | 15 | 10.996 | 0.088 |

| T2 | 27 | 4 | 13 | 10 | ||

| T3 | 62 | 16 | 27 | 19 | ||

| T4 | 111 | 35 | 57 | 19 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| N0 | 63 | 15 | 22 | 26 | 15.845 | 0.0151 |

| N1 | 40 | 9 | 22 | 9 | ||

| N2 | 43 | 7 | 26 | 10 | ||

| N3 | 94 | 32 | 44 | 18 | ||

| TNM stage | ||||||

| I | 44 | 8 | 17 | 19 | 13.543 | 0.0351 |

| II | 55 | 14 | 24 | 17 | ||

| III | 123 | 33 | 65 | 25 | ||

| IV | 18 | 8 | 8 | 2 | ||

| Vessel invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 230 | 62 | 105 | 63 | 7.757 | 0.0211 |

| Positive | 10 | 1 | 9 | 0 | ||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||

| Negative | 222 | 55 | 106 | 61 | 4.191 | 0.123 |

| Positive | 18 | 8 | 8 | 2 | ||

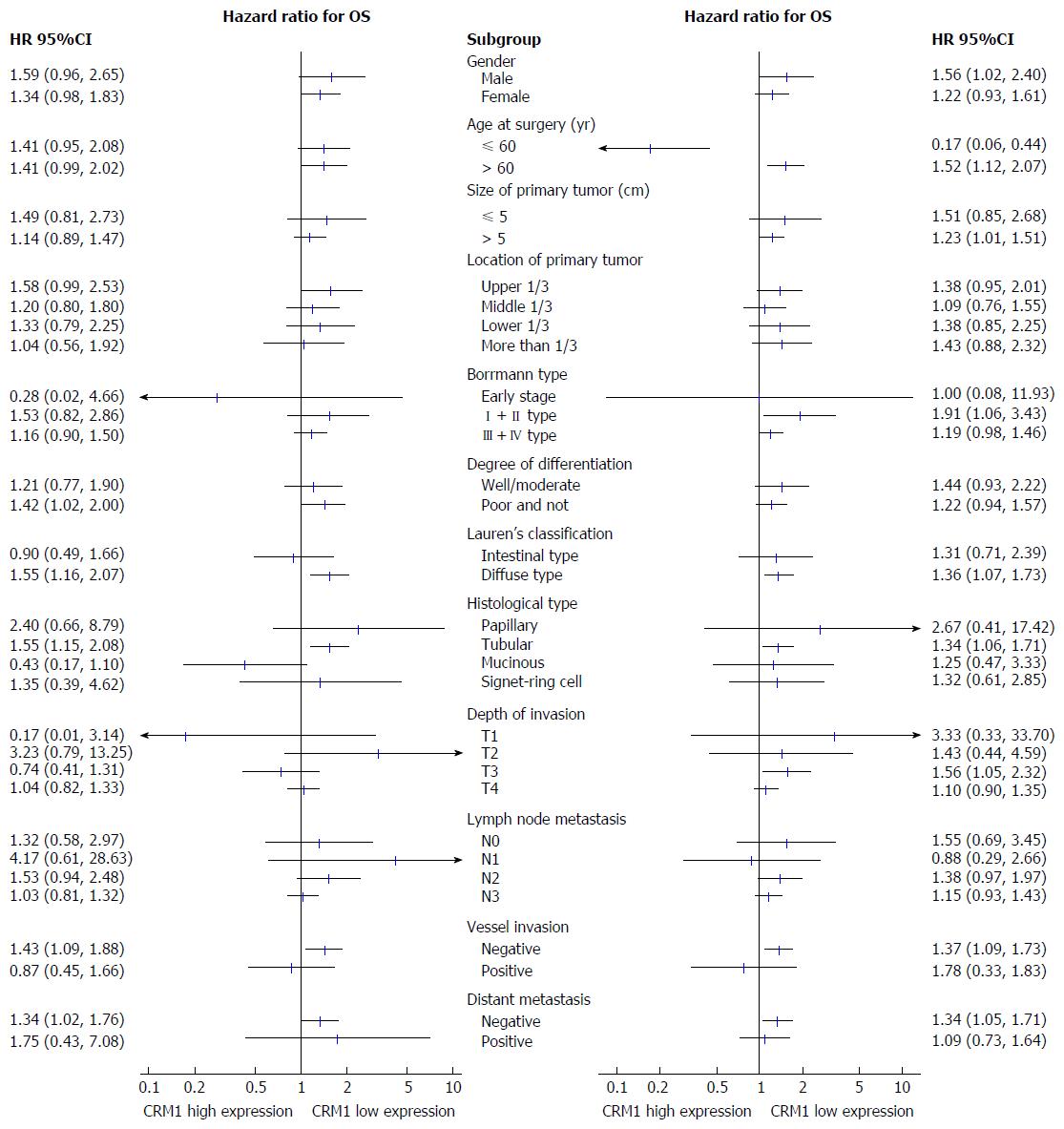

To elucidate the prognostic value of CRM1 and CDK5 expression, univariate Kaplan-Meier and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used. Univariate analysis revealed that OS was significantly associated with size and location of primary tumor, Borrmann type, degree of differentiation, depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, vessel invasion, distant metastasis, CRM1 and CDK5 expression, but not with sex, age at surgery, histological type, and Lauren’s classification (Table 3). The hazard ratio and 95%CI for OS were compared among the subgroups. OS was shorter in patients with low expression of CRM1 or CDK5 in comparison to the corresponding patients with high CRM1 or CDK5 expression (Figure 3).

| Clinicopathological parameters | Cumulative survival rates (%) | Mean survival time (mo) | Log-rank test | P value | |

| 3 yr | 5 yr | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 66.1 | 48.3 | 49.022 | 0.092 | 0.762 |

| Female | 56.6 | 48.0 | 49.324 | ||

| Age at surgery (yr) | |||||

| ≤ 60 | 60.8 | 48.1 | 49.510 | 0.022 | 0.882 |

| > 60 | 57.2 | 47.9 | 49.285 | ||

| Size of primary tumor (cm) | |||||

| ≤ 5 | 84.8 | 73.4 | 66.451 | 44.251 | 0.0001 |

| > 5 | 41.1 | 30.4 | 37.516 | ||

| Location of primary tumor | |||||

| Upper 1/3 | 51.8 | 38.7 | 44.354 | 28.888 | 0.0001 |

| Middle 1/3 | 42.4 | 33.9 | 39.508 | ||

| Lower 1/3 | 76.5 | 66.7 | 61.597 | ||

| More than 1/3 | 31.8 | 22.7 | 30.500 | ||

| Borrmann type | |||||

| Early stage | 90.0 | 90.0 | 72.186 | 41.770 | 0.0001 |

| I + II type | 81.9 | 71.5 | 64.835 | ||

| III + IV type | 42.6 | 30.4 | 38.102 | ||

| Degree of differentiation | |||||

| Well/moderate | 70.8 | 60.3 | 57.397 | 8.644 | 0.0031 |

| Poor and not | 49.8 | 39.9 | 44.056 | ||

| Lauren’s classification | |||||

| Intestinal type | 66.8 | 50.7 | 53.287 | 0.649 | 0.420 |

| Diffuse type | 56.2 | 47.4 | 48.471 | ||

| Histological type | |||||

| Papillary | 57.1 | 57.1 | 50.857 | 1.026 | 0.752 |

| Tubular | 57.2 | 47.0 | 48.339 | ||

| Mucinous | 75.0 | 53.6 | 53.850 | ||

| Signet-ring cell | 60.2 | 48.2 | 51.110 | ||

| Depth of invasion | |||||

| T1 | 97.5 | 94.9 | 78.311 | 64.970 | 0.0001 |

| T2 | 88.9 | 74.1 | 67.889 | ||

| T3 | 59.2 | 46.0 | 48.764 | ||

| T4 | 37.8 | 25.2 | 34.461 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||

| N0 | 88.9 | 80.8 | 70.120 | 59.862 | 0.0001 |

| N1 | 69.5 | 69.5 | 61.079 | ||

| N2 | 58.1 | 34.9 | 43.674 | ||

| N3 | 33.0 | 23.3 | 32.911 | ||

| TNM stage | |||||

| I | 97.7 | 95.4 | 78.211 | 71.616 | 0.0001 |

| II | 76.1 | 61.3 | 60.241 | ||

| III | 40.7 | 29.2 | 38.186 | ||

| IV | 27.8 | 16.7 | 22.518 | ||

| Vessel invasion | |||||

| Negative | 60.8 | 49.3 | 50.492 | 8.264 | 0.0041 |

| Positive | 20.0 | 20.0 | 23.400 | ||

| Distant metastasis | |||||

| Negative | 60.7 | 50.6 | 51.544 | 20.223 | 0.0001 |

| Positive | 16.7 | 16.7 | 22.518 | ||

| CRM1 expression | |||||

| Low | 54.1 | 39.7 | 44.590 | 7.707 | 0.0051 |

| High | 67.0 | 61.5 | 56.540 | ||

| CDK5 expression | |||||

| Low | 49.5 | 39.3 | 53.058 | 6.234 | 0.0131 |

| High | 63.6 | 53.4 | 43.438 | ||

| CRM1/CDK5 expression | |||||

| CRM1 and CDK5 Low | 47.6 | 34.3 | 41.487 | 13.683 | 0.0011 |

| CRM1 or CDK5 Low | 55.9 | 45.2 | 46.873 | ||

| CRM1 and CDK5 High | 73.0 | 66.7 | 61.069 | ||

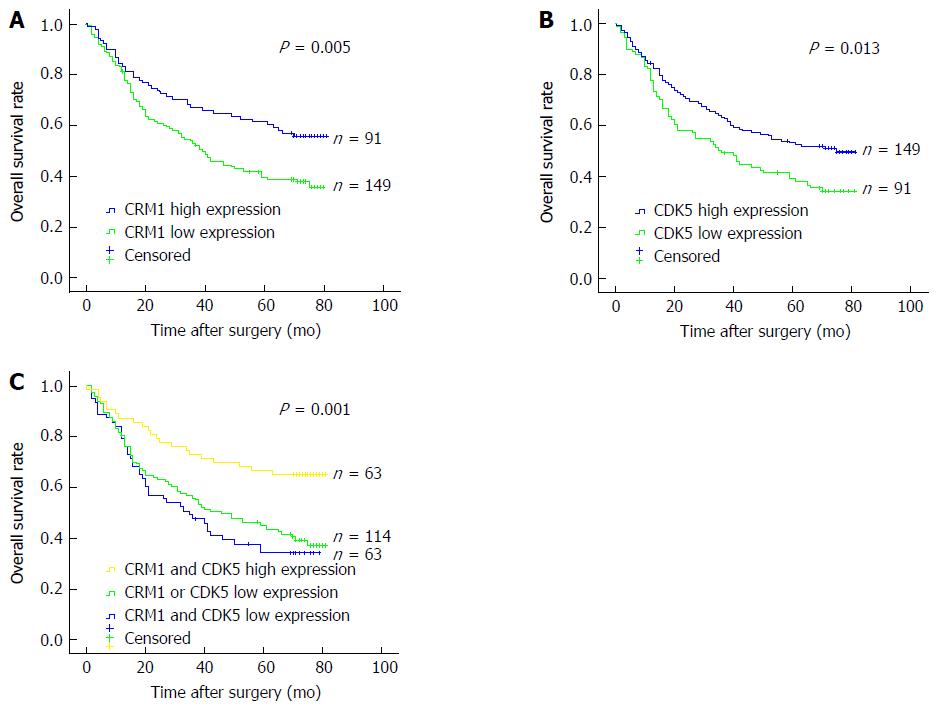

The 3- and 5-year cumulative survival rates were 54.1% and 39.7% for patients with low CRM1 expression, and 67.0% and 61.5% for those with high CRM1 expression. The mean survival time for patients with low and high expression of CRM1 was 44.6 and 56.5 mo, respectively. Clearly, GC patients with low expression of CRM1 had a poorer prognosis than those with high CRM1 expression (P < 0.05) (Figure 4A). The 3- and 5-year cumulative survival rates were 49.5% and 39.3% for GC patients with low expression of CDK5, and 63.6% and 53.4% for those with high CDK5 expression. The mean survival time for GC patients with low and high expression of CDK5 was 43.4 and 53.1 mo, respectively, suggesting a shorter OS for GC patients with low expression of CDK5 (P < 0.05) (Figure 4B).

We evaluated the prognostic value of the combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression. The patients with simultaneous high expression of CRM1 and CDK5 displayed better survival in comparison with the rest of the patients in Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 4C). The 3- and 5-year cumulative survival rates were 47.6% and 34.3% for the simultaneous low CRM1 and CDK5 expression patient group, 55.9% and 45.2% for the CRM1 or CDK5 low expression patient group, and 73.0% and 66.7% for the simultaneous high CRM1 and CDK5 expression patient group, respectively. The mean survival time was 41.5 mo for patients with CRM1 and CDK5 low expression; 46.9 mo for those with CRM1 or CDK5 low expression; and 61.1 mo for those with CRM1 and CDK5 high expression (Table 3).

The clinicopathological parameters that were correlated with patient survival in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis. CRM1 and CDK5 coexpression status, tumor size, tumor location, and TNM stage were independent prognostic factors for patients with GC, whereas vessel invasion and Borrmann type were not (Table 4).

| Covariates | Coefficient | Standard error | HR | 95% CI for HR | P value |

| Tumor location (cardia vs others) | 0.451 | 0.202 | 1.570 | 1.057-2.333 | 0.0261 |

| Tumor size (≥ 5 vs < 5 cm) | 0.723 | 0.232 | 2.060 | 1.309-3.243 | 0.0021 |

| Vessel invasion (positive vs negative) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| TNM stage (stage III and IV vs I and II) | 1.086 | 0.243 | 1.961 | 1.839-4.768 | 0.0001 |

| CDK5 and CRM1 expression | |||||

| (low/high vs high/high) | 0.568 | 0.254 | 1.765 | 1.074-2.903 | 0.0251 |

| (low/low vs high/high) | 0.769 | 0.269 | 2.158 | 1.274-3.657 | 0.0041 |

| Borrmann type (type early, I, II vs III, IV) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

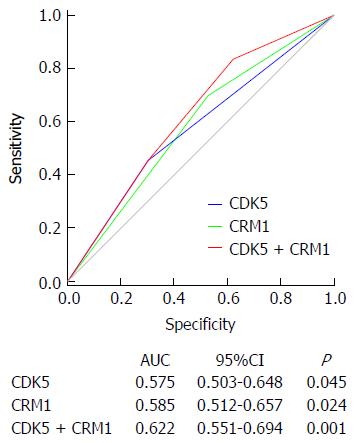

In our previous work, we demonstrated that downregulation of CDK5 in GC was an independent prognostic factor. To improve the prognostic accuracy of OS in GC patients, we combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression to generate a predictive model. ROC analysis was applied to compare the prognostic accuracy between combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression and CRM1 or CDK5 expression alone. Combination of CRM1 and CDK5 expression showed significantly higher prognostic accuracy [area under the curve (AUC): 0.622, 95%CI: 0.551-0.694, P = 0.001] than CRM1 expression alone (AUC: 0.585, 95%CI: 0.512-0.657, P = 0.024) or CDK5 expression alone (AUC: 0.575, 95%CI: 0.503-0.648, P = 0.045) (Figure 5). All these results indicated that the combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression provided better prognostic power for GC patient OS.

Increasing evidence has demonstrated that the karyoplasm localization of CDK5 is important for its multiple pathological and physiological functions, including neuronal migration during brain development, neuronal cell survival and tumor development and progression[23-27]. CDK5 has no intrinsic nuclear localization signal and its nuclear localization relies on p27[12]. In the absence of p27, two weak NESs on CDK5 bind to CRM1, leading to the cytoplasmic shuttle of CDK5[12]. In this study, low CDK5 expression was associated with poorer prognosis (Figure 4B), which was consistent with our previous discovery that CDK5 acted as a tumor suppressor in GC[23]. However, CRM1 is usually considered as an oncogene and involved in the nuclear export of a number of proteins including p53, p21, c-ABL and FOXOs[28-30]. Forgues et al[31] found that cytoplasmic sequestration of CRM1 is frequently associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. In this work, high CRM1 expression was associated with longer GC patient survival (Figure 4A), suggesting that CRM1 exerts a tumor suppressive role in GC. Considering the oncogenic role of CDK5 in many other types of cancer such as hepatocellular carcinoma[24], breast cancer[32] and neuroendocrine thyroid cancer[25], it is possible that the shift of CDK5 function in GC affects the function of CRM1. In addition, we recently found that CDK5RAP3, a binding protein of the CDK5 activator p35, negatively regulates the β-catenin signaling pathway by repressing glycogen synthase kinase-3β phosphorylation and acts as a tumor suppressor in GC[33]. The differential expression or activities of other CDK5-binding partners such as CDK5RAP3 may also affect the functions of CDK5 and CRM1 among different cancer types.

The fact that either CDK5 or CRM1 expression could influence the prognostic power of the other (Figure 4C) seemed to support this hypothesis. Further analysis with ROC revealed that combination of CRM1 and CDK5 expression showed significantly higher prognostic accuracy than CRM1 or CDK5 expression alone (P = 0.001) (Figure 5), indicating that combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression show more prognostic power for OS of patients with GC. Taken together, our present study suggested that CRM1 and CDK5 should receive considerable attention as effective markers for predicting therapeutic outcomes, but the profound molecular roles of CRM1 and CDK5 in GC remain far from being fully elucidated and need further research.

In addition, we found that low CRM1 expression was associated with lymph node metastasis in GC (Table 1). This suggested that the identification of CRM1 expression in preoperative mucosal biopsies from GC patients may indicate the necessity for a more aggressive lymphadenectomy, although further studies in a larger cohort of patients are needed.

In conclusion, our results suggested that combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression was an independent prognostic factor for OS and showed more prognostic power in GC patients. Considering the inferior prognosis of the CRM1 and/or CDK5 low patients, more frequent follow-up is probably needed for these patients after surgery.

To evaluate the prognostic value of the expression of chromosomal maintenance (CRM)1 and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)5 for gastric cancer (GC) patients after gastrectomy.

CDK5 downregulation was an independent prognostic factor and the nuclear localization of CDK5 was critical for its tumor suppressor function in GC. Given that CRM1 regulates CDK5 karyoplasm localization in neurons, we hypothesized that the functional correlation between CRM1 and CDK5 may affect the prognostic power of each molecule. In the present study, we examined the expression of CRM1 and CDK5 in 240 gastric tumor tissues and analyzed their correlation with patient clinicopathological features.

CRM1 and CDK5 coexpression was an independent prognostic factor for patients with GC. The present results suggested that combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression could provide a better prognostic model for overall survival (OS) of GC patients.

The presented results suggested that combined CRM1 and CDK5 expression was an independent prognostic factor for OS of GC patients and showed more prognostic power than individual factors alone. Considering the inferior prognosis of the CRM1 and/or CDK5 low patients, more frequent follow-up is probably needed for these patients after surgery.

The authors investigate whether combined expression of CDK5 and CRM1 correlates with clinic-pathological parameters in GC. The manuscript is sound and the experiments/correlations are well-performed.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Liebl J S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25546] [Article Influence: 1824.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Yang L. Incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:17-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S. The updated incidences and mortalities of major cancers in China, 2011. Chin J Cancer. 2015;34:502-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11444] [Cited by in RCA: 13215] [Article Influence: 1468.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077-3079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 814] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shou ZX, Jin X, Zhao ZS. Upregulated expression of ADAM17 is a prognostic marker for patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;256:1014-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fukuda M, Asano S, Nakamura T, Adachi M, Yoshida M, Yanagida M, Nishida E. CRM1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature. 1997;390:308-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 977] [Cited by in RCA: 1009] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ossareh-Nazari B, Bachelerie F, Dargemont C. Evidence for a role of CRM1 in signal-mediated nuclear protein export. Science. 1997;278:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 601] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stommel JM, Marchenko ND, Jimenez GS, Moll UM, Hope TJ, Wahl GM. A leucine-rich nuclear export signal in the p53 tetramerization domain: regulation of subcellular localization and p53 activity by NES masking. EMBO J. 1999;18:1660-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 538] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saji M, Vasko V, Kada F, Allbritton EH, Burman KD, Ringel MD. Akt1 contains a functional leucine-rich nuclear export sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:167-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | He W, Wang X, Chen L, Guan X. A crosstalk imbalance between p27(Kip1) and its interacting molecules enhances breast carcinogenesis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2012;27:399-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang J, Li H, Herrup K. Cdk5 nuclear localization is p27-dependent in nerve cells: implications for cell cycle suppression and caspase-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14052-14061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lo HW, Ali-Seyed M, Wu Y, Bartholomeusz G, Hsu SC, Hung MC. Nuclear-cytoplasmic transport of EGFR involves receptor endocytosis, importin beta1 and CRM1. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1570-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Noske A, Weichert W, Niesporek S, Röske A, Buckendahl AC, Koch I, Sehouli J, Dietel M, Denkert C. Expression of the nuclear export protein chromosomal region maintenance/exportin 1/Xpo1 is a prognostic factor in human ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1733-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yao Y, Dong Y, Lin F, Zhao H, Shen Z, Chen P, Sun YJ, Tang LN, Zheng SE. The expression of CRM1 is associated with prognosis in human osteosarcoma. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:229-235. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Shen A, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Zou L, Sun L, Cheng C. Expression of CRM1 in human gliomas and its significance in p27 expression and clinical prognosis. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:153-159; discussion 159-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huang WY, Yue L, Qiu WS, Wang LW, Zhou XH, Sun YJ. Prognostic value of CRM1 in pancreas cancer. Clin Invest Med. 2009;32:E315. [PubMed] |

| 18. | van der Watt PJ, Zemanay W, Govender D, Hendricks DT, Parker MI, Leaner VD. Elevated expression of the nuclear export protein, Crm1 (exportin 1), associates with human oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:730-738. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Choi JH, Banks AS, Estall JL, Kajimura S, Boström P, Laznik D, Ruas JL, Chalmers MJ, Kamenecka TM, Blüher M. Anti-diabetic drugs inhibit obesity-linked phosphorylation of PPARgamma by Cdk5. Nature. 2010;466:451-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 780] [Cited by in RCA: 721] [Article Influence: 48.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hisanaga S, Endo R. Regulation and role of cyclin-dependent kinase activity in neuronal survival and death. J Neurochem. 2010;115:1309-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lindqvist J, Imanishi SY, Torvaldson E, Malinen M, Remes M, Örn F, Palvimo JJ, Eriksson JE. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 acts as a critical determinant of AKT-dependent proliferation and regulates differential gene expression by the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:1971-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tripathi BK, Qian X, Mertins P, Wang D, Papageorge A, Carr S, Lowy DR. CDK5 negatively regulates Rho by phosphorylating and activating the Rho-GAP and tumor suppressor functions of DLC1. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1574-1574. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cao L, Zhou J, Zhang J, Wu S, Yang X, Zhao X, Li H, Luo M, Yu Q, Lin G. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 decreases in gastric cancer and its nuclear accumulation suppresses gastric tumorigenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1419-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ehrlich SM, Liebl J, Ardelt MA, Lehr T, De Toni EN, Mayr D, Brandl L, Kirchner T, Zahler S, Gerbes AL. Targeting cyclin dependent kinase 5 in hepatocellular carcinoma--A novel therapeutic approach. J Hepatol. 2015;63:102-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pozo K, Castro-Rivera E, Tan C, Plattner F, Schwach G, Siegl V, Meyer D, Guo A, Gundara J, Mettlach G. The role of Cdk5 in neuroendocrine thyroid cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:499-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Merk H, Zhang S, Lehr T, Müller C, Ulrich M, Bibb JA, Adams RH, Bracher F, Zahler S, Vollmar AM. Inhibition of endothelial Cdk5 reduces tumor growth by promoting non-productive angiogenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:6088-6104. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Zhang J, Li H, Yabut O, Fitzpatrick H, D’Arcangelo G, Herrup K. Cdk5 suppresses the neuronal cell cycle by disrupting the E2F1-DP1 complex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5219-5228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Connor MK, Kotchetkov R, Cariou S, Resch A, Lupetti R, Beniston RG, Melchior F, Hengst L, Slingerland JM. CRM1/Ran-mediated nuclear export of p27(Kip1) involves a nuclear export signal and links p27 export and proteolysis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:201-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Vigneri P, Wang JY. Induction of apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells through nuclear entrapment of BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase. Nat Med. 2001;7:228-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Vogt PK, Jiang H, Aoki M. Triple layer control: phosphorylation, acetylation and ubiquitination of FOXO proteins. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:908-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Forgues M, Difilippantonio MJ, Linke SP, Ried T, Nagashima K, Feden J, Valerie K, Fukasawa K, Wang XW. Involvement of Crm1 in hepatitis B virus X protein-induced aberrant centriole replication and abnormal mitotic spindles. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5282-5292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chiker S, Pennaneach V, Loew D, Dingli F, Biard D, Cordelières FP, Gemble S, Vacher S, Bieche I, Hall J. Cdk5 promotes DNA replication stress checkpoint activation through RPA-32 phosphorylation, and impacts on metastasis free survival in breast cancer patients. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:3066-3078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wang JB, Wang ZW, Li Y, Huang CQ, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Lin JX, Lu J, Chen QY. CDK5RAP3 acts as a tumor suppressor in gastric cancer through inhibition of β-catenin signaling. Cancer Lett. 2017;385:188-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |