Published online Mar 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i9.2861

Peer-review started: September 16, 2015

First decision: November 5, 2015

Revised: November 19, 2015

Accepted: December 8, 2015

Article in press: December 8, 2015

Published online: March 7, 2016

Processing time: 168 Days and 12.2 Hours

We present a rare case of invasive liver abscess syndrome due to Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) with metastatic meningitis and septic shock. A previously healthy, 55-year-old female patient developed fever, liver abscess, septic shock, purulent meningitis and metastatic hydrocephalus. Upon admission, the clinical manifestations, laboratory and imaging examinations were compatible with a diagnosis of K. pneumoniae primary liver abscess. Her distal metastasis infection involved meningitis and hydrocephalus, which could flare abruptly and be life threatening. Even with early adequate drainage and antibiotic therapy, the patient’s condition deteriorated and she ultimately died. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of K. pneumoniae invasive liver abscess syndrome with septic meningitis reported in mainland China. Our findings reflect the need for a better understanding of the epidemiology, risk factors, complications, comorbid medical conditions and treatment of this disease.

Core tip: Invasive liver abscess syndrome due to Klebsiella pneumonia (K. pneumoniae) has been emerging worldwide over the past 2 decades, especially in the Asia Pacific region. K. pneumoniae liver abscess with metastatic meningitis is a rare and devastating complication. To our knowledge, this is the first case of invasive liver abscess syndrome with septic meningitis due to K. pneumoniae reported in mainland China.

- Citation: Qian Y, Wong CC, Lai SC, Lin ZH, Zheng WL, Zhao H, Pan KH, Chen SJ, Si JM. Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive liver abscess syndrome with purulent meningitis and septic shock: A case from mainland China. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(9): 2861-2866

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i9/2861.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i9.2861

Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) is a Gram-negative, non-motile, capsulated, gas-producing enteric bacillus widely found in nature, and it belongs to the normal flora of the human oral cavity and intestine. K. pneumoniae was first discovered by Friedlander in 1882 and considered to be responsible for a severe form of lobar pneumonia[1]. Infections with K. pneumoniae are usually hospital-acquired and occur primarily in patients with impaired host defenses. On the other hand, it has emerged that K. pneumoniae is a major cause of rare, community-acquired mono-microbial pyogenic liver abscess (69.0%-73.2%)[2,3].

Recently, there is a rising consensus that K. pneumoniae primary liver abscess (KLA) can be defined as a K. pneumoniae liver abscess occurring in the absence of predisposing hepatobiliary disease[4]. KLA was first described in Taiwan[5] and the majority of the KLA were found in patients of Asian descent[4,6], although KLA has also been found in a Caucasian man in 2011[7]. In the past, KLA had been considered rare in mainland China[8]. The mortality rate of patients with KLA is 2.8%-8.0%[5,9,10]. Extrahepatic metastatic infection at distant sites has been reported in 8.7% to 15.5% of KLA patients, which may result in severe complications and poor outcomes[11-13]. In 2012, Fang et al[5] proposed a case definition for invasive liver abscess syndrome: K. pneumoniae liver abscess with extrahepatic complications, especially involvement of central nervous system (CNS), necrotising fasciitis or endophthalmitis[9]. Invasive K. pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome is generally community-acquired and presents mainly as a mono-microbial liver abscess. A reported 13% of patients with this syndrome have septic metastatic ocular or CNS lesions[5].

Importantly, invasive liver abscess syndrome with metastatic infections due to K. pneumoniae is associated with high morbidity and mortality[9]. Among these distal metastatic infections, meningitis secondary to K. pneumoniae primary liver abscess is a life-threatening condition and is observed in 4%-10% of the cases with KLA[5,12], whose rate of mortality or a permanent vegetative state can reach up to 44%-49%[14,15].

Whilst this syndrome has been reported in East Asia, North America and South Africa[4,6,10,16-19], to the best of our knowledge, KLA with metastatic meningitis has not been reported in mainland China. Here we present a rare case of a previously healthy 55-year-old female patient who developed fever, liver abscess, septic shock, purulent meningitis and metastatic hydrocephalus. Given the devastating nature of metastatic meningitis secondary to KLA, our case will raise concern for this globally emerging invasive syndrome among clinicians.

A 55-year-old female resident of Zhejiang province, China, was admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, and presented with a chief complaint of 10 d of abdominal discomfort, anorexia and 1 wk of fever and dizziness. In the ED she experienced an episode of diarrhea, but had no other gastrointestinal symptoms. Her past medical history was unremarkable, and there had been no recent travel, tick bites, sick contact, alcohol or drug use. On admission her initial vital signs included a body temperature of 39.5 °C, heart rate of 103 beats/min, blood pressure of 127/61 mmHg, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on 3 L/min oxygen. The scleras were non-icteric and the neck was supple. The lungs were clear bilaterally, with no audible murmur on cardiac auscultation. Tenderness could be elicited in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, but hepatosplenomegaly was not detected. Neurologic examination was unremarkable. No rash was observed.

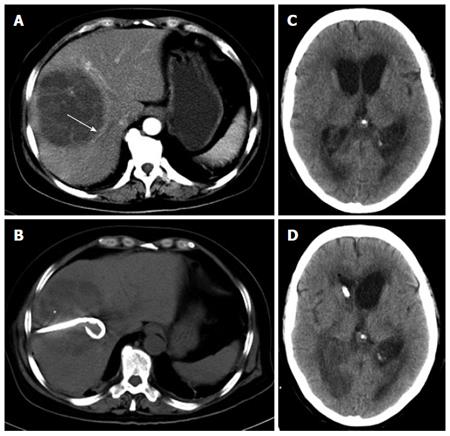

Laboratory test results included a white blood cell count of 19.8 × 109/L with an elevated neutrophil ratio of 89.9%. The concentrations of C-reactive protein and glucose were 109.9 mg/L and 7.48 mmol/L, respectively. Liver function test results were as follows: aspartate aminotransferase: 150 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase: 86 IU/L; lactate dehydrogenase: 431 IU/L; total bilirubin: 15.0 μmol/L; and direct bilirubin: 7.4 μmol/L. Coagulation panel demonstrated an international normalized ratio of 1.19, prothrombin time of 14.9 s, and partial thromboplastin time of 37.5 s. Lactate was 0.9 mmol/L. Two sets of peripheral blood cultures were ordered. Because of the right upper quadrant tenderness on physical examination, a further imaging examination was performed. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a single abscess in the right lobe of liver (84 mm × 91 mm) (Figure 1A). No other intra-abdominal pathologies such as gallstones were observed. Because the patient also suffered from high fever and dizziness, a head CT scan was performed at the same time, which had no acute findings. The patient was diagnosed with primary liver abscess and sepsis, and thus she was immediately treated with intravenous meropenem and emergency CT-guided percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess (SKATERTM Drainage Catheter-Locking Pigtail, 8 French) was performed, which drained 300 mL of yellow pus over the first 24 h (Figure 1B). The liver aspirate was submitted for Gram stain and both aerobic and anaerobic culture. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit after drainage, when her heart rate was 92 beats/min and blood pressure was 121/70 mmHg. Repeated blood and liver pus cultures were ordered during episodes of fever.

On the 2nd day after admission, the patient continued to suffer from high fever and chills. The highest body temperature was 39 °C. Blood pressure fluctuated and sometimes the MBP dropped below 65 mmHg. She was drowsy and unresponsive to physical or verbal stimuli and commands. GCS score was 2 + 3 + 5. Bulbar conjunctival edema and stiff neck were observed. Pupillary examination revealed equal and reactive pupils. Under suspicion of meningitis, the patient received a second head CT plain scan and underwent lumbar puncture examination. CT images demonstrated hydrocephalus with diffuse cerebral edema (Figure 1C). The intracranial pressure was 120 mm H2O. Cerebrospinal fluid was yellow and purulent, and revealed 9630 white blood cells/μL, 140 red blood cells/μL, protein 2343 mg/L and glucose 0.24 mmol/L. Cerebrospinal fluid was submitted for Gram staining and bacterial culture. The above findings led to the diagnosis of purulent meningitis and hydrocephalus, and septic shock could not be excluded. Meropenem combined with vancomycin were then given intravenously.

On the morning of the 3rd day, the patient’s blood pressure dropped to 84/52 mmHg with a pulse rate of 62 beats/min. Norepinephrine was given to maintain MBP > 65 mmHg. The body temperature fluctuated between 37.9 °C and 39 °C. The patient developed extreme drowsiness and was awake only to painful stimuli. Upper limb spasm was occasionally observed. A third head plain CT scan revealed hydrocephalus, which was more severe than that of the first two scans. Considering the patient was in a hemodynamically unstable condition, contrast-enhanced CT of the head was not allowed. But even in the absence of imaging data, we could deduce the diagnosis of brain abscess based on her clinical symptoms, the lab results of CSF and consecutive plain CT scans of head. Based on this diagnosis, emergency lateral ventricular drainage was given. During the operation, intracranial hypertension and purulent cerebrospinal fluid were observed and the cerebrospinal fluid was collected for routine examination, biochemistry and culture. The tests showed 16420 white blood cells/μL, 130 red blood cells/μL, protein 2198 mg/L and glucose 0.18 mmol/L. Five hours post-operation, the patient’s mental status improved and her body temperature returned to normal. Post-operative head CT scan demonstrated that hydrocephalus was improved (Figure 1D).

On the 4th day, the patient regained consciousness, and the GCS score was 3 + T + 6. Her body temperature was normal and the hemodynamic status was stable. She was kept on ventilation and SPO2 was 100% (FiO2 was 40%). Considering that the drainage of the cerebral ventricular empyema remained inadequate, bilateral ventricular drainage was proposed but was refused by the patient’s family. Eventually she was transferred to a local hospital for personal reasons.

K. pneumoniae was subsequently isolated from two independent liver aspirate samples. The isolate was resistant to ampicillin but susceptible to broad-spectrum antibiotics such as cephalosporins, ampicillin-sulbactam, levofloxacin, aminoglycosides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and meropenem. On the other hand, both blood and CSF failed to isolate any microorganism; Gram staining was also negative, despite the presence of a large amount of neutrophilic inflammatory cells in the CSF. We followed up this patient by phone; however, her condition deteriorated and she died two weeks later.

Both host and virulence factors contribute to the pathogenesis of invasive liver abscess syndrome. Apart from an impaired host defense, KLA has been significantly associated with underlying diabetes mellitus as compared to non-K. pneumonia primary liver abscess, especially in the patients who developed metastatic infection[20]. It is generally accepted that an increased blood-glucose level can inhibit phagocyte chemotaxis, phagocytosis and bactericidal activity, and contributes to bacterial growth and a compromised host defense system[21,22]. But until now, existing published data are still conflicting as to whether diabetes is an independent risk factor for metastatic infection.

Several bacterial virulence factors have been investigated for their involvement in the pathogenesis of invasive liver abscess syndrome, and have often been found to be related to the bacterial capsule. K. pneumoniae strains harboring capsular serotype K1 or K2, mucoviscosity-associated gene A (magA), rmpA, and aerobactin appear to be highly virulent. Such bacterial virulence factors are associated with the development of metastatic disease. However, the rmpA gene is almost ubiquitous in KLA strains, thus rmpA could hardly predict metastatic infections among patients with KLA[23]. Our patient was a healthy middle-aged woman and had no known putative host risk factor such as history of diabetic mellitus or immunodeficiency. Therefore, bacterial virulence factors are more likely to be the predominant factor. However, the K. pneumoniae strain was not further investigated to determine the capsular serotype or other virulence genes at the time.

Currently, there are no clear guidelines for the management of invasive liver abscess syndrome. A combination of early percutaneous drainage or open (laparoscopic) surgical drainage of the abscess and prompt appropriate antibiotic administration is the standard protocol for treating this condition. The majority of community acquired K. pneumoniae isolates are resistant only to ampicillin and sensitive to cephalosporins[13]. No KLA-specific practice guideline regarding antibiotic treatment exists so far. In Taiwan, KLA patients without metastatic complications receive standard treatments including percutaneous pigtail catheter drainage and parenteral sensitive antibiotics (cefazolin plus gentamicin) for 4-5 wk, and oral cephalosporin for the following 2-3 mo to prevent relapse. In patients with metastatic complications, a third generation cephalosporin will be recommended[24]. A prospective clinical cohort study from Singapore proposed a further 16 d (IQR 10-22) of intravenous therapy through the outpatient parenteral antimicrobial treatment service, especially when a prolonged intravenous antibiotic is required[25]. A multi-center clinical trial designed to compare the efficacy of 4 wk of intravenous antibiotics to early step-down to oral antibiotics in KLA patients is underway in Singapore[26]. With the advances in interventional radiology, percutaneous drainage is more widely used[27], but aggressive hepatic resection has been observed to have a better prognosis for patients with acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II (APACHE II) scores of 15 or greater[28]. In a series of 80 patients, Tan et al[29] found that for liver abscesses larger than 5 cm, surgical drainage resulted in better outcomes than percutaneous drainage in terms of treatment success and the necessity for secondary procedures.

In this report, we describe the first case of K. pneumoniae invasive liver abscess syndrome with purulent meningitis and septic shock in mainland China. We present this rare case to raise concern for this globally emerging invasive syndrome among clinicians. This case not only illustrates K. pneumoniae invasive liver abscess syndrome as a devastating disease that can progress rapidly, but also the need for urgent diagnosis and treatment. Inquiry into comorbid history, careful physical examination, dynamic radiological investigations of distal infection sites, immediate and repeated bacteria cultures and susceptibility tests are advocated for making rapid detection and diagnosis of KLA and recognition of possible invasive complications. Quick capsular serotyping, bacteria-associated virulent factor detection, emergent specialist consultation and early adequate drainage are recommended, aiming at early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, thus preventing catastrophic metastatic complications, minimizing occurrence of sequelae and improving clinical outcomes ultimately. Among them, prompt drainage and an optimized antibiotic protocol remain the cornerstones of therapy. As for the metastasis meningitis, consecutive head CT scans are recommended.

A rare case of primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) in a previously healthy, 55-year-old female patient who developed fever, liver abscess, septic shock, purulent meningitis and metastatic hydrocephalus.

The patient was diagnosed with K. pneumonia invasive liver abscess syndrome with metastatic meningitis and septic shock.

The differential diagnoses of patients with a focal liver lesion include malignant and infectious etiologies; computed tomography and liver aspirate culture can usually differentiate liver abscess from tumor.

The diagnosis of K. pneumoniae primary liver abscess was deduced after K. pneumoniae was subsequently isolated from two independent liver aspirate samples.

Abdominal computerized tomographic (CT) scan demonstrated a single large multi-loculated abscess in the right lobe of the liver, and a series of brain CT scans revealed brain edema and hydrocephalus.

The patient was only given CT-guided percutaneous drainage of liver abscess and emergency lateral ventricular drainage, so no pathological findings available.

Besides early intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics, adequate CT-guided percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess and emergency lateral ventricular drainage were given.

A research group reported that GCS score could predict the outcome of bacterial meningitis.

K. pneumoniae invasive liver abscess syndrome is defined as K. pneumoniae liver abscess with extrahepatic complications, which has high morbidity and mortality.

Dynamic image examination of distal infection sites and immediate and repeated bacteria cultures are critical for recognition of possible invasive complications due to K. pneumoniae liver abscess.

It was possible to isolate K. pneumoniae from CSF, so immediate and repeated bacteria Gram staining and cultures are recommended, which will contribute to rapid diagnosis of K. pneumoniae invasive liver abscess syndrome. But it’s still a nicely written case report of an interesting case.

P- Reviewer: Chiu KW, Sunbul M, Wong VWS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Simoons-Smit AM, Verwey-van Vught AM, Kanis IY, MacLaren DM. Virulence of Klebsiella strains in experimentally induced skin lesions in the mouse. J Med Microbiol. 1984;17:67-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chung SD, Keller J, Lin HC. Greatly increased risk for prostatic abscess following pyogenic liver abscess: a nationwide population-based study. J Infect. 2012;64:445-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang CC, Yen CH, Ho MW, Wang JH. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscess caused by non-Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37:176-184. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, Holzman RS. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1654-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fang CT, Lai SY, Yi WC, Hsueh PR, Liu KL, Chang SC. Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype K1: an emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:284-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 430] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lederman ER, Crum NF. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:322-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fierer J, Walls L, Chu P. Recurring Klebsiella pneumoniae pyogenic liver abscesses in a resident of San Diego, California, due to a K1 strain carrying the virulence plasmid. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:4371-4373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shen DX, Wang J, Li DD. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:390-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 600] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alsaif HS, Venkatesh SK, Chan DS, Archuleta S. CT appearance of pyogenic liver abscesses caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Radiology. 2011;260:129-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chung DR, Lee SS, Lee HR, Kim HB, Choi HJ, Eom JS, Kim JS, Choi YH, Lee JS, Chung MH. Emerging invasive liver abscess caused by K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. J Infect. 2007;54:578-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee SS, Chen YS, Tsai HC, Wann SR, Lin HH, Huang CK, Liu YC. Predictors of septic metastatic infection and mortality among patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:642-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang JH, Liu YC, Lee SS, Yen MY, Chen YS, Wang JH, Wann SR, Lin HH. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1434-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fang CT, Chen YC, Chang SC, Sau WY, Luh KT. Klebsiella pneumoniae meningitis: timing of antimicrobial therapy and prognosis. QJM. 2000;93:45-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lu CH, Chang WN, Chang HW. Klebsiella meningitis in adults: clinical features, prognostic factors and therapeutic outcomes. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:533-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zinn RL, Pruitt K, Eguchi S, Baylin SB, Herman JG. hTERT is expressed in cancer cell lines despite promoter DNA methylation by preservation of unmethylated DNA and active chromatin around the transcription start site. Cancer Res. 2007;67:194-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nadasy KA, Domiati-Saad R, Tribble MA. Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae syndrome in North America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:e25-e28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pomakova DK, Hsiao CB, Beanan JM, Olson R, MacDonald U, Keynan Y, Russo TA. Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumonia: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:981-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Saccente M. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess, endophthalmitis, and meningitis in a man with newly recognized diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1570-1571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang J, Yan Y, Xue X, Wang K, Shen D. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscesses caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae and non-Klebsiella pneumoniae pathogens in Beijing: a retrospective analysis. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:1088-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lin YT, Wang FD, Wu PF, Fung CP. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in diabetic patients: association of glycemic control with the clinical characteristics. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hagiya H, Kuroe Y, Nojima H, Otani S, Sugiyama J, Naito H, Kawanishi S, Hagioka S, Morimoto N. Emphysematous liver abscesses complicated by septic pulmonary emboli in patients with diabetes: two cases. Intern Med. 2013;52:141-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chuang YC, Lee MF, Tan CK, Ko WC, Wang FD, Yu WL. Can the rmpA gene predict metastatic meningitis among patients with primary Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess? J Infect. 2013;67:166-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Moore R, O’Shea D, Geoghegan T, Mallon PW, Sheehan G. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: an emerging infection in Ireland and Europe. Infection. 2013;41:681-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chan DS, Archuleta S, Llorin RM, Lye DC, Fisher D. Standardized outpatient management of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e185-e188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Molton J, Phillips R, Gandhi M, Yoong J, Lye D, Tan TT, Fisher D, Archuleta S. Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | O’Farrell N, Collins CG, McEntee GP. Pyogenic liver abscesses: diminished role for operative treatment. Surgeon. 2010;8:192-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hsieh HF, Chen TW, Yu CY, Wang NC, Chu HC, Shih ML, Yu JC, Hsieh CB. Aggressive hepatic resection for patients with pyogenic liver abscess and APACHE II score > or =15. Am J Surg. 2008;196:346-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tan YM, Chung AY, Chow PK, Cheow PC, Wong WK, Ooi LL, Soo KC. An appraisal of surgical and percutaneous drainage for pyogenic liver abscesses larger than 5 cm. Ann Surg. 2005;241:485-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |