Published online Feb 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i8.2642

Peer-review started: June 12, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Revised: August 5, 2015

Accepted: October 12, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

Published online: February 28, 2016

Processing time: 260 Days and 21.2 Hours

Type IV paraesophageal hernia (PEH) is very rare, and is characterized by the intrathoracic herniation of the abdominal viscera other than the stomach into the chest. We describe a 78-year-old woman who presented at our emergency department because of epigastric pain that she had experienced over the past 24 h. On the day after admission, her pain became severe and was accompanied by right chest pain and dyspnea. Chest radiography revealed an intrathoracic intestinal gas bubble occupying the right lower lung field. Emergency explorative laparotomy identified a type IV PEH with herniation of only the terminal ileum through a hiatal defect into the right thoracic cavity. In this report, we also present a review of similar cases in the literature published between 1980 and 2015 in PubMed. There were four published cases of small bowel herniation into the thoracic cavity during this period. Our patient represents a rare case of an individual diagnosed with type IV PEH with incarceration of only the terminal ileum.

Core tip: Type IV paraesophageal hernias (PEH) is very rare, occurring in only 2%-5% of all PEH cases. The clinical course of PEH may present with minimal symptoms, but potentially life-threatening complications such as strangulation, necrosis, or perforation could occur. Early recognition and prompt therapy of these hernias and associated comorbidities are crucial.

- Citation: Hsu CT, Hsiao PJ, Chiu CC, Chan JS, Lin YF, Lo YH, Hsiao CJ. Terminal ileum gangrene secondary to a type IV paraesophageal hernia. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(8): 2642-2646

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i8/2642.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i8.2642

Hiatal hernias are classified into four types: more than 95% are type I or sliding hernias[1], whereas less than 5% are paraesophageal hernias (PEH) (types II-IV)[1]. Type IV PEH is very rare, comprising only 2%-5% of all cases[2], and is defined by the intrathoracic herniation of the abdominal viscera other than the stomach into the chest. Sporadic cases of hiatal hernias of the stomach plus the colon, greater omentum, mesentery, or small bowel; the colon alone; or the gastric volvulus alone have been reported[3]. However, herniation of the terminal ileum without the involvement of the other abdominal components has rarely been reported. The initial symptoms of PEH may be subtle, and can therefore be neglected or else lead to misdiagnosis. PEH merits separate consideration from the more commonly diagnosed sliding hiatal hernia owing to the possibility of life-threatening complications such as strangulation, necrosis, or perforation[1]. In reporting the rare case of a terminal ileum within an incarcerated PEH without involvement of the abdominal viscera, we highlight the importance of careful differential diagnosis and early treatment of such conditions to avoid life-threatening complications.

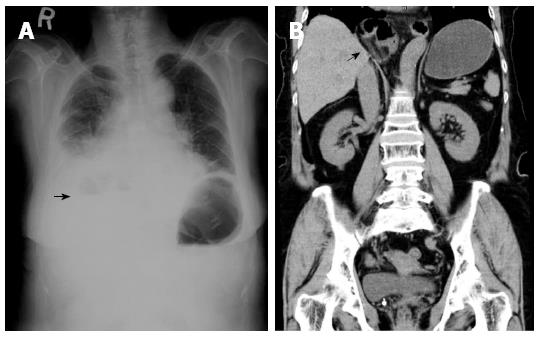

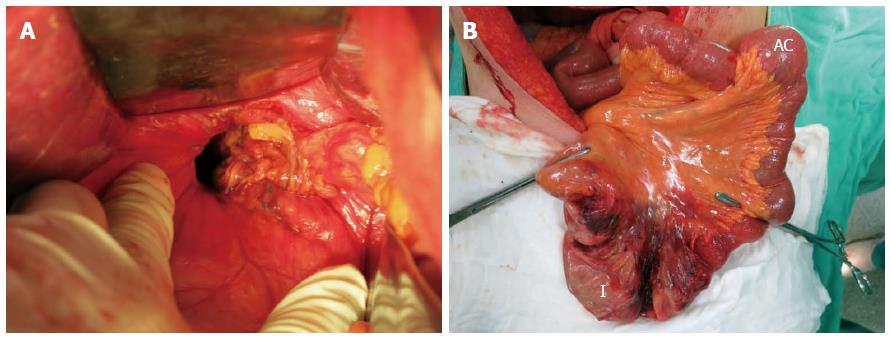

A previously healthy 78-year-old woman presented at our emergency department with epigastric pain and nausea experienced over the past 24 h. She reported no trauma or surgery. On examination, the epigastrium was tender but findings were otherwise unremarkable. Initially, a blood test revealed a normal white blood cell count of 8530 cells/mm3, a hemoglobin level of 11.8 g/dL, and normal electrolyte levels. One day after admission, her epigastric pain became severe and was accompanied by right chest pain and dyspnea. Examination revealed epigastric tenderness with positive bowel sounds and absent breath sounds at the right lung base. We repeated the blood test; this time, there were abnormalities as follows: white blood count, 30890 cells/mm3; band neutrophils, 26%; creatine phosphokinase, 528 U/L; and C-reactive protein, 25.2 mg/dL. Plain chest radiography (Figure 1A) revealed an intrathoracic intestinal gas bubble occupying the right lower lung field and an air-fluid level. Subsequent computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen (Figure 1B) revealed a large segment of the small intestine within the right thoracic cavity. Upon emergency explorative laparotomy, the terminal ileum was found to be incarcerated within a hiatal defect (Figure 2A); however, the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) was located in its normal anatomic position. The terminal ileum was found to be strangulated and gangrenous. The surgeon resected approximately 50 cm of the ischemic terminal ileum (Figure 2B) with primary anastomosis. The hiatal defect, 5 cm long, was repaired with a prolene mesh. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged 17 d after admission.

Hiatal hernia is a condition in which portions of the abdominal contents, mainly the GEJ and stomach, are proximally displaced above the diaphragm through the esophageal hiatus into the mediastinum[4]. Hiatal hernias can be classified into four types[1]. Type I is a sliding hernia that occurs when the GEJ migrates into the posterior mediastinum through the hiatus because of laxity of the phrenoesophageal ligament[5,6]. Types II, III, and IV hiatal hernias are known as PEH. Type II is the classic form of PEH, which occurs when the fundus herniates through the hiatus alongside a normally positioned GEJ by a defect in the phrenoesophageal membrane[2]. Type III is a combination of type I and II hernias with the GEJ and stomach cranially displaced through the hiatus. Type IV is characterized by the displacement of the stomach plus other organs such as the colon, spleen, and small bowel into the chest. Our patient was diagnosed with type IV PEH on the basis of her terminal ileum herniating through a hiatal defect into the thoracic cavity, while the GEJ was in its normal location.

Sporadic cases of hiatal hernias of the stomach along with the colon, greater omentum, mesentery, or small bowel, or otherwise only the colon or the gastric volvulus, have been reported[3]. Prolapse of peritoneal organs other than the stomach into the thoracic cavity is rare. As shown in Table 1, only 5 patients (including our patient) with type IV PEH involving incarceration of the small bowel have been reported[3,7-9]. Our patient’s diagnosis, a type IV PEH with incarceration of only the terminal ileum, is extremely rare.

| Reference/year | Age/sex | Symptom | Involved organ | Ischemia | Therapy |

| Ohtsuka et al[7], 2012 | 78/female | Abdominal pain | Stomach and Small bowel (ileum) | No | laparotomy |

| Pappachan et al[8], 2013 | 78/female | syncope | Small bowel and colon | No | No |

| Ho et al[3], 2014 | 78/female | Abdominal pain and vomiting | Stomach omentum and small bowel (ileum) | Yes | laparotomy |

| Makris et al[9], 2015 | 66/male | Epigastric pain and dyspnea | Small bowel (ileum only) | Yes | laparotomy |

| Our case | 78/female | Epigastric pain and dyspnea | Small bowel (terminal ileum only) | Yes | laparotomy |

More than 50% of patients with PEHs are asymptomatic, and many of the symptoms that do occur are minor and may be overlooked[1]. Typical symptoms of hiatal hernias include chest pain, epigastric pain, dysphagia, postprandial fullness, heartburn, regurgitation, vomiting, weight loss, anemia, and respiratory symptoms[10]. Patients may present with severe epigastric pain caused by incarceration and/or obstruction. If obstruction persists, ischemia, necrosis, perforation, and septic shock may ensue. The presence of severe epigastric tenderness, chest pain, and dyspnea are grounds for considering a differential diagnosis of type IV PEH. Plain chest radiography often identifies a PEH as a retrocardiac air-fluid level within the intrathoracic stomach or intestine. CT scanning is a helpful tool to assess the widening of the esophageal hiatus, PEH size, content, and position. PEH merits additional attention compared to the more common sliding hiatal hernia because of life-threatening complications such as strangulation, necrosis, or perforation that may develop[1]. Providing immediate, intensive surgical intervention is crucial to prevent deterioration.

Acute incarceration of PEH is a surgical emergency presenting with sudden chest pain, abdominal pain, or dyspnea. This development can be so rapid that the patient can present on admission with respiratory failure or systemic sepsis, as in the case of our patient. This can be due to strangulation, necrosis, or perforation of the abdominal viscera, and can lead to abdominal emergencies. Options for performing a PEH repair include the laparoscopic approach, open laparotomy, and open thoracotomy. Traditionally, acute incarceration of PEH has been treated with open surgery, through either the abdomen or the chest, and has been accompanied by high rates of morbidity and mortality, especially among older patients[11]. However, there are no clear guidelines for emergency treatment of PEH by laparoscopic or open intervention. One meta-analysis study that included 20 patients suggested that emergency open surgery should be indicated when a patient presents with clear clinical evidence of acute ischemia, obstruction, or perforation[12]. Another meta-analysis of 64 patients suggested that laparoscopic repair should be attempted whenever possible, even in emergency settings, but recognized that conversion to open repair may be required if ischemia or perforation is identified[11]. Based upon these observations, the presence of clinical evidence of ischemia, obstruction, or perforation can determine whether to perform a PEH repair by laparoscopy or by an open approach in abdominal emergency cases. Emergency laparoscopic repair of PEH is safe and feasible in selected patients, and an emergency open repair may be required to manage the suspected ischemia and necrosis of the herniated viscus.

The optimal operative approach, whether laparoscopic or open, has been debated extensively[13]. The benefits of laparoscopic PEH repair include low morbidity, short hospital stay, and rapid recovery; these are crucial aspects for elderly patients[12]. However, some published studies have reported a high hernia recurrence rate after laparoscopic PEH repair[14]. A meta-analysis of 13 retrospective studies including 965 patients who underwent laparoscopic repair reported an overall hernia recurrence rate of 10.2% (range, 3%-33%)[15]. In fact, the true recurrence rate was 25.5% when a video barium esophagram was used to assess the repair[15]. Additionally, the laparoscopic approach has a steep learning curve and requires advanced laparoscopic experience to perform safely and effectively. Other PEH repair methods include thoracotomy or laparotomy. Laparotomy still plays an important role in an emergency context and has a low recurrence rate, ranging from 2.5% to 13%[16]. In contrast to laparoscopy, it is characterized by slower recovery, higher incidence of wound infections, poorer mediastinal visualization, and more challenging transhiatal dissection[16]. Transthoracic repair can provide a better view of the herniated structures, easier sac dissection and resection, and better mobilization of the esophagus[17]. Disadvantages of a thoracotomy include incisional discomfort, pulmonary complications, prolonged hospital stay, as well as difficulty assessing the intra-abdominal organs. A retrospective study of 240 patients undergoing primary transthoracic repair reported a 10% anatomic recurrence rate[13]. Hence, surgeons should carefully consider the risk of complications and the possible reduction in recurrence rates before selecting the best intervention method.

The incidences of esophageal hiatal hernia are increasing as the population ages; approximately 60% of individuals > 50 years of age are affected by this condition[18]. In elderly adults, an increase in the laxity of the diaphragmatic crus forming the esophageal hiatus, as well as high abdominal pressure that causes enlargement of the esophageal hiatus, may cause hiatal hernias[19]. Early recognition of symptoms associated with type IV PEH is critical. Physicians should be alert to the possibility of type IV PEH in patients presenting with rapid onset of severe epigastric tenderness along with chest pain and dyspnea, especially in older individuals. This report highlights the importance of careful differential diagnosis and early treatment of PEH to avoid life-threatening sequelae.

A previously healthy 78-year-old woman presented with epigastric pain and nausea that progressed to dyspnea and right chest pain after admission.

The patient exhibited positive bowel sounds and absent breath sounds at the right lung base.

Peptic ulcer perforation, lung abscess, and pneumothorax were considered.

The patient had an elevated white blood cell count of 30890 cells/mm3, band neutrophil content of 26%, creatine phosphokinase of 528 U/L, and C-reactive protein of 25.2 mg/dL.

Plain chest radiography revealed an intrathoracic intestinal gas bubble occupying the right lower lung field and an air-fluid level; computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a large segment of small intestine within the right thoracic cavity.

Sections of the terminal ileum showed evidence of ischemic bowel disease with marked mural infarction; furthermore, marked transmural ischemic necrosis with dense inflammatory cell infiltration was observed.

Emergency explorative laparotomy was performed: approximately 50 cm of the ischemic terminal ileum was resected and the hiatal defect (5 cm) was repaired with a prolene mesh.

Herniation of the stomach along with the abdominal viscera is the most common presentation of type IV paraesophageal hernia (PEH); colon- or pancreas-only herniation has also been reported.

Type IV PEH is a hernia characterized by displacement of the stomach in addition to other organs, such as the colon, spleen, and small bowel, into the chest.

This case not only represents the first reported type IV PEH involving the incarceration of only the terminal ileum and no other abdominal visceral organs, but also provides a differential diagnosis in elderly adults with symptoms of severe epigastric and chest pains, and describes early treatment to avoid life-threatening complications.

Case report on a paraesophageal hernia combined with an incarcerated segment of terminal ileum. A rare case with short overview of existing literature and illustrative images.

P- Reviewer: Klinge U, Losanoff JE, Palermo M, Scheidbach H S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Kissane NA, Rattner DW. Paraesophageal and other complex diaphragmatic hernias. Shackelford’s Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. Amsterdam: Elsevier Medicine 2013; 494-508. |

| 2. | Maish MS, Demeester SR. Paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Current surgical therapy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby 2004; 38-42. |

| 3. | Ho MP, Tsai KC, Cheung WK, Chou AH. Hiatal hernia with gastric volvulus and small bowel strangulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:994-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hyun JJ, Bak YT. Clinical significance of hiatal hernia. Gut Liver. 2011;5:267-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Peridikis G, Hinder RA. Paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott 1995; 544-554. |

| 7. | Ohtsuka Y, Ogasawara T, Nakano S, Shida T, Nomura S, Sato Y, Takahashi M. [A case of complex (type IV) paraesophageal hiatal hernia with herniation of the small intestine]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2012;113:58-61. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Pappachan JM, Gill G, Machin A, Walker AB. Medical image. A giant type IV hiatus hernia with colonic and small bowel loops within it. N Z Med J. 2013;126:182-183. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Makris MC, Moris D, Yettimis E, Varsamidakis N. Type IV paraesophageal hernia as a cause of ileus: Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;6C:43-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pierre AF, Luketich JD, Fernando HC, Christie NA, Buenaventura PO, Litle VR, Schauer PR. Results of laparoscopic repair of giant paraesophageal hernias: 200 consecutive patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:1909-1915; discussion 1915-1916. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Shaikh I, Macklin P, Driscoll P, de Beaux A, Couper G, Paterson-Brown S. Surgical management of emergency and elective giant paraesophageal hiatus hernias. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bawahab M, Mitchell P, Church N, Debru E. Management of acute paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:255-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patel HJ, Tan BB, Yee J, Orringer MB, Iannettoni MD. A 25-year experience with open primary transthoracic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:843-849. [PubMed] |

| 14. | White BC, Jeansonne LO, Morgenthal CB, Zagorski S, Davis SS, Smith CD, Lin E. Do recurrences after paraesophageal hernia repair matter? : Ten-year follow-up after laparoscopic repair. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1107-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rathore MA, Andrabi SI, Bhatti MI, Najfi SM, McMurray A. Metaanalysis of recurrence after laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. JSLS. 2007;11:456-460. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Davis SS. Current controversies in paraesophageal hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:959-978, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mungo B, Molena D, Stem M, Feinberg RL, Lidor AO. Thirty-day outcomes of paraesophageal hernia repair using the NSQIP database: should laparoscopy be the standard of care? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Goyal Raj K; Chapter 286. Diseases of the esophagus. In: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 17th ed. . |

| 19. | Cole TJ, Turner MA. Manifestations of gastrointestinal disease on chest radiographs. Radiographics. 1993;13:1013-1034. [PubMed] |