Published online Dec 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10371

Peer-review started: September 1, 2016

First decision: September 12, 2016

Revised: October 9, 2016

Accepted: November 28, 2016

Article in press: November 28, 2016

Published online: December 21, 2016

Processing time: 113 Days and 10.4 Hours

To evaluate the risks of medical conditions, evaluate gastric sleeve narrowing, and assess hydrostatic balloon dilatation to treat dysphagia after vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG).

VSG is being performed more frequently worldwide as a treatment for medically-complicated obesity, and dysphagia is common post-operatively. We hypothesize that post-operative dysphagia is related to underlying medical conditions or narrowing of the gastric sleeve. This is a retrospective, single institution study of consecutive patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy from 2013 to 2015. Patients with previous bariatric procedures were excluded. Narrowing of a gastric sleeve includes: inability to pass a 9.6 mm gastroscope due to stenosis or sharp angulation or spiral hindering its passage.

Of 400 consecutive patients, 352 are included; the prevalence of dysphagia is 22.7%; 33 patients (9.3%) have narrowing of the sleeve with 25 (7.1%) having sharp angulation or a spiral while 8 (2.3%) have a stenosis. All 33 patients underwent balloon dilatation of the gastric sleeve and dysphagia resolved in 13 patients (39%); 10 patients (30%) noted resolution of dysphagia after two additional dilatations. In a multivariate model, medical conditions associated with post-operative dysphagia include diabetes mellitus, symptoms of esophageal reflux, a low whole blood thiamine level, hypothyroidism, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and use of opioids.

Narrowing of the gastric sleeve and gastric sleeve stenosis are common after VSG. Endoscopic balloon dilatations of the gastric sleeve resolves dysphagia in 69% of patients.

Core tip: Vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) is rapidly becoming the most commonly performed bariatric surgical procedure. Post-operative dysphagia is present in 22.7% of patients after VSG. Medical conditions significantly associated with post-operative dysphagia include diabetes mellitus, symptoms of esophageal reflux, low whole blood thiamine level, hypothyroidism, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and use of opioids. After VSG, 9.3% of patients develop narrowing of the gastric sleeve. In patients with dysphagia after sleeve gastrectomy and evidence for narrowing of the gastric sleeve, hydrostatic balloon dilatations of the gastric sleeve leads to resolution of dysphagia in 69% of patients.

- Citation: Nath A, Yewale S, Tran T, Brebbia JS, Shope TR, Koch TR. Dysphagia after vertical sleeve gastrectomy: Evaluation of risk factors and assessment of endoscopic intervention. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(47): 10371-10379

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i47/10371.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10371

Obesity is a leading predisposing factor internationally for multiple chronic diseases[1] including hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, osteoarthritis, asthma, and decreased health status. The rapid rise in the prevalence of overweight [Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25] and obese (BMI ≥ 30) individuals is concerning and has been described as a global pandemic[1]. In the years between 1980 and 2013, the worldwide combined prevalence of overweight and obesity individuals increased by 47.1% for children and 27.5% for adults[2].

Dietary and activity program or the addition of weight loss medications generally do not induce sufficient weight loss or provide long term maintenance of weight loss[3,4], especially for individuals with medically-complicated obesity. Surgical interventions have been shown to result in more effective and sustained weight loss as compared to non-surgical interventions in multiple randomized controlled and cohort studies[5,6].

Vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) is a newer and effective surgical option for the management of medically-complicated obesity[7]. VSG was initially introduced as a modification of the biliopancreatic diversion, but was then combined with the duodenal switch[7] as a staged procedure (to try to reduce the complication rate). In the early report by Hess et al[7], gastrectomy was performed by stapling alongside a 40 French dilator passed along the lesser curvature of the stomach. VSG became more commonly performed for treatment of medically-complicated obesity after it was reported to be effective in producing weight loss as the first stage of this modified procedure[8]. VSG is now the most commonly performed bariatric surgery in the United States and of 196000 bariatric surgeries performed in 2015, 53.8% were VSG[9]. VSG is also the second most common bariatric surgery worldwide. According to a worldwide survey from 2013, 37% of 468609 bariatric surgeries were a VSG[10].

VSG is mainly a restrictive procedure in which the gastric fundus and body are surgically excised, leaving a narrow, lesser-curvature based stomach[11]. Despite proven benefits in the management of medically-complicated obesity, VSG can produce complications including a leak or perforation along the staple line, bleeding, significant gastroesophageal reflux, gastric fistula, dilation of the gastric sleeve, inadequate weight loss, and stenosis of the gastric sleeve[12-14].

Dysphagia and postoperative emesis are commonly encountered after sleeve gastrectomy[13,14], but few studies have simultaneously addressed the causes of and the treatment of this complication. Given the rapid rise in the number of VSGs performed, gastroenterologists will be frequently consulted for dysphagia in patients with history of VSG. The suggested treatment strategies to manage narrowing of the gastric sleeve include conservative medical therapy, endoscopic hydrostatic balloon dilation, pneumatic achalasia balloon dilation, or surgical intervention[13-15]. Due to a lack of evidence, currently there are no guidelines for a standardized management plan for symptomatic narrowing of the gastric sleeve after VSG[15].

Our hypothesis is that post-operative dysphagia is related to underlying medical conditions or narrowing of the gastric sleeve. The primary aims of this study of individuals who have undergone VSG include: evaluation of the risks of medical conditions that may be associated with post-operative dysphagia, evaluation of the prevalence of narrowing of the gastric sleeve in patients presenting for post-operative dysphagia, and assessment of hydrostatic balloon dilatation of the gastric sleeve as a symptomatic treatment of VSG patients with post-operative dysphagia.

Approval for human studies was obtained from the Human Studies Subcommittee of MedStar Research Institute (Hyattsville, MD, United States) on December 17, 2015. This is a retrospective, single institution study performed in a large, urban community hospital. Clinical and endoscopic electronic medical records of 400 consecutive patients who underwent VSG in our Center for Bariatric Surgery from 2013 to 2015 have been reviewed.

This study includes individuals of age 18 years old or above who have a BMI > 34.9 kg/m2 and who underwent VSG. Exclusion criteria includes a history of a prior bariatric procedure, less than 6 mo of follow up after surgery, onset of dysphagia less than 2 wk after VSG, and identification of pregnancy during post-operative visits (for a total of 48 individuals).

Briefly, all VSG procedures were performed laparoscopically and included staple line reinforcement. After initial mobilization of the greater curvature of the stomach by division of the gastrocolic and gastrosplenic ligaments, a 36 French Maloney dilator was then passed along the lesser curvature of the stomach to the pylorus. An Ethicon Echelon Stapler with a 60 mm length cartridge was used to perform the gastrectomy. The gastrectomy specimen was then removed from the abdomen through an epigastric port site.

The standard protocol for our bariatric program includes our suggesting that all patients begin one daily multivitamin with minerals prior to VSG and then increase to using two daily multivitamins with minerals after VSG for the first one year. Routine follow up for patients who underwent VSG were scheduled at 2 wk, 6 wk, and 6 mo post-operatively, and then every 6 mo thereafter. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and opioid use are recorded at each visit. For patients with dysphagia, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and use of opioid is recorded at the onset of dysphagia. Since the mean time period to the onset of dysphagia is 13 wk, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and use of opioids in patients with dysphagia at 6 wk follow up is compared to documentation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and opioid use at 6 wk follow up in patients without dysphagia.

A survey of national bariatric programs by the Ad Hoc Nutrition Committee of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery reported that initiating a mechanically altered soft diet is recommended ≥ 2 wk post-operatively[16]. We therefore include dysphagia that began ≥ 2 wk after VSG in our final analysis. Each patient’s age, sex, race, weight, height, body mass index, history of diabetes mellitus, medication history, serum vitamin B12 level, folic acid level, whole blood thiamine level, thyroid function tests, magnesium levels, presence of nausea with emesis, abdominal pain, constipation, symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, dysphagia, and the post-operative time of onset of dysphagia are recorded.

All patients with symptomatic dysphagia had been offered upper endoscopy to look for the presence of mucosal changes such as esophagitis, gastric sleeve stenosis, or ulceration. Narrowing of the gastric sleeve is defined by either an inability to pass a 9.6 mm Olympus video gastroscope due to stenosis of the gastric sleeve or sharp angulation or a spiral of the gastric sleeve hindering passage of a 9.6 mm Olympus gastroscope. Endoscopic reports are reviewed to record presence of narrowing of the gastric sleeve. All of the patients with narrowing of the gastric sleeve had been offered endoscopic hydrostatic balloon dilation using a Boston Scientific through-the-scope controlled radial expansion (CRE) single use esophageal balloon dilator with balloon inflations of 10 mm to 18 mm for 1 min periods. Patients with recurrent or persistent symptoms and narrowing of the gastric sleeve were offered repeat dilatations of their gastric sleeve in order to achieve resolution of symptoms. The clinical outcomes of these interventions are recorded.

Statistical analysis has been performed by a biomedical statistician. In our statistical analysis of the continuous variables, differences in the averages between two groups are tested by two sample t-test when normality assumption is satisfied. The non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test is used when normality assumption is not satisfied. χ2 and Fisher exact (when cells have counts less than 5) tests as appropriate are used to investigate differences for categorical variables between groups. A P-value ≤ 0.05 is accepted as a statistically significant difference. For multiple categorical variables associated with dichotomous outcome, stepwise multiple logistic regressions is performed to develop a multivariate model. The confounding factor is corrected for the variables in logistic regression. The results are reported as OR and 95%CI.

Of 400 consecutive patients who underwent VSG with our three bariatric surgeons in our Center for Bariatric Surgery from 2013 to 2015, 352 study subjects are included in the final analysis and 48 subjects were not included due to our exclusion criteria. As shown in Table 1, the mean age of the study population is 47.0 years old (± 10.8) with a range of 19 to 75 years. The pre-operative mean body mass index is 47.5 kg/m2 with a range of 35 to 82 kg/m2. This is a female-predominant study and 84% of the study subjects are women. The majority (79%) of this study population is African-American, which is representative of the predominant population served by our hospital center.

| Characteristics | Value |

| Total patients (n) | 352 |

| Age (yr) | |

| mean ± SD | 47.0 ± 10.8 |

| Range | 19-75 |

| Gender | |

| Women | 296 (84.1%) |

| Men | 56 (15.9%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |

| Mean | 47.5 ± 8.2 |

| Range | 35-82 |

| Race | |

| African-American | 277 (78.7%) |

| Caucasian | 61 (17.3%) |

| Other | 14 (4.0%) |

Out of the 352 study subjects, 80 individuals (22.7%) report an onset of dysphagia at up to 2 years during their follow up after VSG. The mean time to the onset of symptoms is 13.1 wk (range: 2-60 wk) in these 80 patients.

As shown in Table 2, there is increased prevalence of diabetes mellitus in those individuals who develop postoperative dysphagia compared to individuals with no dysphagia (P < 0.01). Patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux (P < 0.0001) show an increased risk toward the development of postoperative dysphagia. There is also a statistically significant relationship between postoperative dysphagia and low whole blood thiamine levels (P = 0.008), low thyroid blood test (P = 0.003), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use at 6 wk post-operatively (P = 0.018), and opioid narcotic use at 6 wk post-operatively (P = 0.05) as determined through stepwise logistic regression (summarized in Tables 2 and 3). No statistical correlation between age, gender, body mass index, abnormal vitamin B12 level, abnormal folic acid level, or abnormal magnesium level and post-operative dysphagia is seen (see Table 2).

| Characteristics | Dysphagia (n = 80) | No dysphagia (n = 272) | P value |

| Age | 48.0 ± 11.0 | 46.7 ± 10.7 | 0.32 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 47.8 ± 8.4 | 47.4 ± 8.3 | 0.72 |

| Gender | n = 80 | n = 272 | 0.19 |

| Female | 71 (88.8) | 225 (82.7) | |

| Male | 9 (11.3) | 47 (17.3) | |

| Race | n = 80 | n = 272 | 0.038 |

| African-American | 66 (82.5) | 211 (77.6) | |

| Caucasian | 9 (11.3) | 52 (19.1) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Others | 5 (6.3) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | n = 80 | n = 272 | 0.006 |

| Yes | 36 (45.0) | 78 (28.7) | |

| No | 44 (55.0) | 194 (71.3) | |

| Symptom of esophageal reflux | n = 80 | n = 272 | < 0.0001 |

| Yes | 55 (68.8) | 44 (16.2) | |

| No | 25 (31.3) | 228 (83.8) | |

| Normal blood thiamine level | n = 42 | n = 106 | 0.008 |

| Yes | 31 (73.8) | 96 (90.6) | |

| No | 11 (26.2) | 10 (9.4) | |

| Normal vitamin B12 level | n = 45 | n = 117 | 0.49 |

| Yes | 42 (93.3) | 117 (95.9) | |

| No | 3 (6.7) | 5 (4.1) | |

| Normal serum folic acid level | n = 43 | n = 119 | 0.46 |

| Yes | 42 (97.7) | 118 (99.2) | |

| No | 1 (2.3) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Normal thyroid function test | n = 36 | n = 83 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 28 (77.8) | 80 (96.4) | |

| No | 8 (22.2) | 3 (3.6) | |

| Normal serum magnesium level | n = 20 | n = 27 | 0.57 |

| Yes | 18 (90.0) | 26 (96.3) | |

| No | 2 (10.0) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| NSAID use (6 wk follow up) | n = 80 | n = 272 | 0.017 |

| Yes | 25 (31.3) | 51 (18.8) | |

| No | 55 (68.8) | 221 (81.3) | |

| Opioid use (6 wk follow up) | n = 80 | n = 272 | 0.05 |

| Yes | 15 (18.8) | 29 (10.7) | |

| No | 65 (81.3) | 243 (89.3) |

| Effect | Point estimate | 95% Wald confidence limits | |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 2.035 | 1.218 | 3.399 |

| Esophageal reflux symptoms | 11.397 | 6.430 | 20.201 |

| Low blood thiamine level | 3.406 | 1.321 | 8.784 |

| Low thyroid blood testing | 7.619 | 1.888 | 30.740 |

| NSAID use at 6 wk | 1.970 | 1.122 | 3.456 |

| Opioid use at 6 wk | 2.183 | 1.093 | 4.361 |

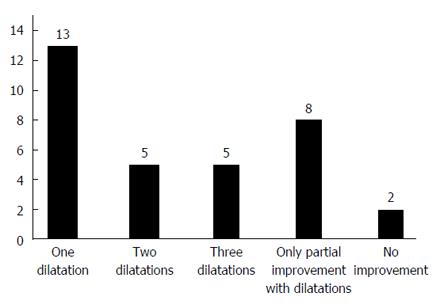

Out of 80 patients with dysphagia, 55 patients agreed to undergo upper endoscopy. Thirty-three of these patients (9.3% of the total study population) have narrowing of their gastric sleeve. Among these 33 individuals, 25 (7.1% of the total study population) have sharp angulation or spiral of the gastric sleeve while 8 (2.3% of the total study population) have evidence for stenosis of the gastric sleeve. All of these 33 individuals with narrowing of their gastric sleeve underwent endoscopic hydrostatic balloon dilation as an initial intervention. As shown in Figure 1, among these 33 study subjects, 13 individuals (39.4%) note resolution of their symptoms after a single dilation, 5 individuals (15.2%) required two sessions of dilation for symptomatic relief, 5 individuals (15.2%) required three sessions of balloon dilation for symptomatic relief, while 8 individuals (24.2%) obtained only partial symptomatic resolution after multiple hydrostatic balloon dilations of their gastric sleeve. Two (6%) individuals describe no clinical improvement despite multiple balloon dilations of their gastric sleeve.

Dysphagia is a commonly encountered symptom after VSG[13-15]. A novel feature of this present study is the use of a multivariate analysis to examine potential medical risk factors in individuals with post-operative dysphagia after VSG; individuals with endoscopic evidence for narrowing of their gastric sleeve are simultaneously treated by hydrostatic balloon dilatation of the sleeve to try to obtain relief from dysphagia. Individuals with immediate (up to 2 wk post-operative) dysphagia were excluded from our study population. Any individual with immediate post-operative dysphagia is excluded because most patients will experience mild symptoms of swallowing difficulty immediately after VSG. An immediate post-operative symptom of dysphagia may be due to edema of the gastric staple line, inflammation of the gastric mucosa after the procedure, or the use of opioids for post-operative pain[13,14]. Subacute to chronic dysphagia persisting after two weeks requires careful follow-up evaluation since it may evolve into a chronic and disabling disorder inducing malnutrition, which is an indication for consideration of revisional surgery with conversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass[12].

There is presently a paucity of data with regards to the prevalence of dysphagia as a postoperative complication after VSG. We evaluated the prevalence of dysphagia after VSG and its time of onset after this surgical procedure. In our present study, the prevalence of postoperative dysphagia was 22.7% (excluding dysphagia symptoms during the first two weeks after the procedure) and the mean time of onset was 13.1 wk (range: 2-60 wk) among the 352 patients who underwent VSG at our Center for Bariatric Surgery. In support of our first hypothesis, statistical analysis does identify multiple medical conditions associated with dysphagia after VSG.

In our patient population, the odds of developing dysphagia is 2.035 (95%CI: 1.22-3.40) in patients with a history of diabetes mellitus prior to VSG (P = 0.006). Abnormal gastrointestinal motility is a recognized complication of longstanding diabetes mellitus and has been attributed to gut autonomic neuropathy leading to reduced contractility[17]. In a large population based survey by Bytzer and associates of 8657 individuals, diabetes mellitus was associated with an increased prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms as compared with controls[18]. In a case-control study of 40 patients by Horowitz et al[19], delayed upper gastrointestinal emptying was related to plasma glucose concentrations and occurred more frequently in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. In addition to hyperglycemia, pre-existing gut autonomic neuropathy in diabetic patients could further exacerbate dysphagia.

In our patient population, the odds of developing dysphagia is 7.62 (95%CI: 1.89-30.74) in patients with low blood thyroid level (P = 0.003). Gastrointestinal motility and thyroid hormone levels are closely related. Studies have shown that hypothyroidism prominently decreased gastroesophageal motility via reduced velocity and amplitude of esophageal peristalsis with a decrease in lower esophageal sphincter pressure[20,21]. In our study, a significantly higher proportion of patients with dysphagia have low thyroid hormone levels compared to those without dysphagia, supporting evaluation of thyroid function testing in patients with dysphagia after VSG.

Out of the 352 patients in this study, whole blood thiamine levels are available in 148 individuals. Low whole blood thiamine levels are present in 26.2% of patients with dysphagia compared to 9.4% of patients with no dysphagia (P = 0.008). In our patient population, the odds of developing dysphagia is 3.406 (95%CI: 1.32-8.78) in patients with a low whole blood thiamine level. Stores of thiamine can become depleted as quickly as within 2 to 3 wk, and thiamine deficiency commonly involve multiple organ systems[22,23]. Symptoms of nausea, vomiting and dysphagia have been observed in a significant proportion of individuals with thiamine deficiency[22,23]. Thiamine deficiency is a known complication of bariatric surgery, and in a previous prospective study we found an 18% prevalence of thiamine deficiency in patients after gastric bypass surgery[24]. In parallel work, Van Rutte et al[25] reported a 5.5% prevalence of thiamine deficiency one year after VSG, while Saif et al[26] reported thiamine deficiency in 14.3% and 30.8% of patients 3 years and then 5 years after VSG.

In our patient population, the odds of developing dysphagia is 11.397 (95%CI: 6.43-20.20) in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux (P = 0.001). Documented symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux or evidence for reflux esophagitis at upper endoscopy is seen in 68.8% of our patients with dysphagia compared to 16.2% of patients without dysphagia. In previous work, authors had reported improvement in the preexisting symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux after VSG[12,27]. However, a complex interplay of anatomical and physiologic factors after VSG could contribute to worsening of reflux. Braghetto et al[28] examined the effects of VSG on the lower esophageal sphincter. A hypotensive lower esophageal sphincter was observed in 85% of their patients at 6 mo after VSG. Baumann et al[29] evaluated post-operative changes after VSG with multislice computed tomography. Out of the 27 patients, 10 had proximal migration of the staple line, with 4 of these patients complaining of persistent regurgitation despite continuous acid suppressive therapy. Using high-resolution impedance manometry with 24-h pH and intraluminal impedance, Del Genio et al[30] demonstrated an increase in ineffective esophageal peristalsis, incomplete bolus transit, and retrograde flow within the esophagus. Similar to a hiatal hernia, dilated fundus may function as a reservoir predisposing to reflux[31]. Yehoshua et al[32] demonstrated low distensibility of the sleeve by peri-operatively insufflating the abdomen with carbon dioxide; therefore removal of the majority of fundus may result in reduced accommodation.

In our present study, the odds of developing dysphagia is 1.97 (95%CI: 1.12-3.46) in patients receiving a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug for 6 wk after VSG (P = 0.016). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use can commonly cause esophageal mucosal injury in the form of non-reflux esophagitis. Zayachkivska et al[33] reported that naproxen increased the corneal and epithelial cell layer thickness of the esophagus and produced disorganization of the muscle plate and irregular submucosal edema. The authors documented that naproxen suppressed endogenous hydrogen sulfide synthesis, a critical factor for submucosal protection and repair[33].

Our present study shows that the odds of developing dysphagia is 2.183 (95%CI: 1.09-4.36) in patients taking opioids for 6 wk after VSG (P = 0.05). The effects of opioids on esophageal function and motility may benefit from further study. Studies using healthy volunteers showed that morphine decreased lower esophageal sphincter relaxation[34]. Case series documented dysphagia in patients receiving intrathecal fentanyl, possibly secondary to a central effect[35,36]. A retrospective study examined patients who received opioids and developed dysphagia[37]; the authors documented manometric abnormalities including abnormal lower esophageal sphincter relaxation during swallows, hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter, spastic achalasia-like esophageal dysmotility, and abnormal esophageal body contractions[37].

In our present study, the prevalence of gastric sleeve stenosis in patients who underwent VSG is 2.3%, in agreement with previously reported prevalence of 0.1% to 3.9%[38-43]. At upper endoscopy we also identify 25 patients (or 7.1% of our study population) who have sharp angulation or a spiral of the gastric sleeve. Hydrostatic balloon dilatation of the gastric sleeve leads to resolution of dysphagia in 39% of patients, while two additional sessions of dilatation of the gastric sleeve leads to resolution of dysphagia in 30% of patients with persistent dysphagia. In support of our second hypothesis, narrowing of the gastric sleeve is associated with dysphagia after VSG.

Narrowing or stenosis of the gastric sleeve is known to cause dysphagia after VSG[44]. We define stenosis in our study as obstruction of passage through the gastric sleeve. Mechanical gastric sleeve stenosis has been proposed to be caused by retraction of scar, oversewing of the staple line at VSG, overtraction of the greater curvature during stapling, or small hematomas or leaks which heal as scar tissue[44,45]. Sharp angulation or a spiral of the gastric sleeve could result from an incomplete gastric sleeve stenosis or other mechanisms such as asymmetrical lateral traction while stapling leading to twisting of the gastric tube in a volvulus-like mechanism[46]. There could be indentation of the incisura angularis within the gastric lumen creating a flap-valve[47] or a small Bougie dilator could create too tight of a sleeve in an area where gastric contents cannot readily pass[38,48,49].

For acute dysphagia, rehydration involves intravenous fluids or frequent sips of small volumes of fluids. Suggested management of subacute or chronic gastric sleeve stenosis has included therapeutic endoscopic intervention and surgical procedures[13,14,38,40,50]. Therapeutic endoscopic interventions include hydrostatic balloon dilatation with a repeat session as needed at 4 to 6 wk[49,51,52] or use of a pneumatic achalasia balloon dilator. Parikh et al[53] identified “short-segment” gastric sleeve stenosis in 8 patients out of 230 patients who underwent VSG, and endoscopic balloon dilatation successfully resolved symptoms in all 8 patients with a mean of 1.6 dilatations. Proposed surgical interventions include revision of the sleeve gastrectomy, seromyotomy, or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Due to the paucity of data, there are presently no guidelines for the management of symptomatic gastric sleeve stenosis after VSG[15].

Since this is a retrospective study, it shares limitations with other retrospective studies which include difficulty controlling for all variables, difficulty minimizing the compliance of study subjects with regards to our recommendations, difficulty with determination of sample size (a power analysis could not be performed because we were uncertain what the effect size would be), and there is difficulty assessing the temporal relationships. In addition, our study contains a large proportion of African-American females from the Northeast United States and so we are uncertain whether our study results can be extrapolated to other patient populations.

In conclusion, post-operative dysphagia is reported by 22.7% of patients in up to 2 years of follow up after VSG. Medical conditions that are significantly associated with post-operative dysphagia include diabetes mellitus, symptoms of esophageal reflux, a low whole blood thiamine level, hypothyroidism, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and the use of opioids. After VSG, 9.3% of patients develop stenosis or sharp angulation of the gastric sleeve. Hydrostatic balloon dilatation of the gastric sleeve leads to resolution of dysphagia in 39% of patients, while two additional sessions of dilatation of the gastric sleeve leads to resolution of dysphagia in 30% of patients with persistent dysphagia.

The prevalence of overweight and obese individuals has continued to rise worldwide. Surgical interventions have been shown to result in more effective and sustained weight loss as compared to non-surgical interventions. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) is a newer bariatric surgical procedure for treatment of individuals with medically-complicated obesity and is mainly a restrictive procedure in which the gastric fundus and body are surgically excised, leaving a narrow, lesser-curvature based stomach. VSG is now the second most common bariatric surgical procedure being performed worldwide. Important complications after VSG include gastric perforation and dysphagia.

Narrowing or stenosis of the gastric sleeve is known to cause dysphagia after VSG. It has been suggested that gastric sleeve stenosis can be caused by retraction of scar, oversewing of the staple line at VSG, overtraction of the greater curvature during stapling, or small hematomas or leaks which heal as scar tissue. Therapeutic endoscopic interventions proposed to treat narrowing or stenosis of the gastric sleeve include hydrostatic balloon dilatation or use of a pneumatic achalasia balloon dilator. The effectiveness of dilation for treatment of dysphagia after VSG is not well understood. The contributions of potential medical conditions to the development of dysphagia after VSG are unclear.

In a previous study of patients who underwent VSG, short-segment gastric sleeve stenosis was identified in 8 patients out of 230 total patients. Endoscopic balloon dilatation successfully resolved symptoms in these 8 patients with a mean of 1.6 dilatations of the gastric sleeve. In the present study, the authors aimed to investigate the effectiveness of dilation of the gastric sleeve by endoscopic hydrostatic balloon dilation for treatment of postoperative dysphagia. In the present study, the authors aimed to investigate the contributions of potential medical conditions to the development of dysphagia after VSG by using stepwise multiple logistic regressions.

Identification of medical conditions that may contribute to the development of dysphagia in postoperative patients after VSG may permit the incorporation of additional preventative care in the postoperative program of patients. Preventative care may reduce the prevalence of postoperative dysphagia in individuals who undergo VSG.

Narrowing of the gastric sleeve is defined by either an inability to pass a 9.6 mm Olympus video gastroscope due to stenosis of the gastric sleeve, or sharp angulation of or a spiral of the gastric sleeve hindering passage of a 9.6 mm Olympus gastroscope.

This article is interesting and provides some important information about the incidence, risk factors for developing dysphagia following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and some useful information about the endoscopic treatment for this complication.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hawasli A, Garcia-Olmo D, Kassir R, Leitman M, Welbourn R S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

| 1. | Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012;70:3-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2709] [Cited by in RCA: 2398] [Article Influence: 184.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7951] [Cited by in RCA: 8006] [Article Influence: 727.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Hollis JF, Loria CM, Vollmer WM, Gullion CM, Funk K, Smith P. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139-1148. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Montesi L, El Ghoch M, Brodosi L, Calugi S, Marchesini G, Dalle Grave R. Long-term weight loss maintenance for obesity: a multidisciplinary approach. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:37-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, Lystig T, Sullivan M, Bouchard C, Carlsson B. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741-752. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Arterburn DE, Olsen MK, Smith VA, Livingston EH, Van Scoyoc L, Yancy WS, Eid G, Weidenbacher H, Maciejewski ML. Association between bariatric surgery and long-term survival. JAMA. 2015;313:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hess DS, Hess DW. Biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch. Obes Surg. 1998;8:267-282. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Regan JP, Inabnet WB, Gagner M, Pomp A. Early experience with two-stage laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as an alternative in the super-super obese patient. Obes Surg. 2003;13:861-864. [PubMed] |

| 9. | “Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2015” American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, n. d. Web. Available from: https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. |

| 10. | Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1822-1832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1221] [Cited by in RCA: 1165] [Article Influence: 116.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Rashti F, Gupta E, Ebrahimi S, Shope TR, Koch TR, Gostout CJ. Development of minimally invasive techniques for management of medically-complicated obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13424-13445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Rutte PW, Smulders JF, de Zoete JP, Nienhuijs SW. Sleeve gastrectomy in older obese patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2014-2019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Walsh C, Karmali S. Endoscopic management of bariatric complications: A review and update. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:518-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sarkhosh K, Birch DW, Sharma A, Karmali S. Complications associated with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: a surgeon’s guide. Can J Surg. 2013;56:347-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ogra R, Kini GP. Evolving endoscopic management options for symptomatic stenosis post-laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: experience at a large bariatric surgery unit in New Zealand. Obes Surg. 2015;25:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aills L, Blankenship J, Buffington C, Furtado M, Parrott J, and the Allied Health Sciences Section Ad Hoc Nutrition Committee. ASMBS allied health nutritional guidelines for the surgical weight loss patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:S73-S108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Camilleri M, Malagelada JR. Abnormal intestinal motility in diabetics with the gastroparesis syndrome. Eur J Clin Invest. 1984;14:420-427. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with diabetes mellitus: a population-based survey of 15,000 adults. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1989-1996. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Horowitz M, Harding PE, Maddox A, Maddern GJ, Collins PJ, Chatterton BE, Wishart J, Shearman DJC. Gastric and oesophageal emptying in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Gastroent Hepatol. 1986;1:97-113. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Eastwood GL, Braverman LE, White EM, Vander Salm TJ. Reversal of lower esophageal sphincter hypotension and esophageal aperistalsis after treatment for hypothyroidism. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1982;4:307-310. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ciobanu L, Dumitrascu DL. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in endocrine diseases. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2011;121:129-136. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Williams RD, Mason HI, Power MH, Wilder RM. Induced thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency in man; relation of depletion of thiamine to development of biochemical defect and of polyneuropathy. JAMA Int Med. 1943;71:38-53. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Prinzo ZW. Thiamine deficiency and its prevention and control in major emergencies. WHO/NHD/99/13. 1999;1-52 Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/emergencies/ WHO_NHD_99.13/en/. |

| 24. | Shah HN, Bal BS, Finelli FC, Koch TR. Constipation in patients with thiamine deficiency after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Digestion. 2013;88:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | van Rutte PW, Aarts EO, Smulders JF, Nienhuijs SW. Nutrient deficiencies before and after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1639-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Saif T, Strain GW, Dakin G, Gagner M, Costa R, Pomp A. Evaluation of nutrient status after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy 1, 3, and 5 years after surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:542-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Casella G, Soricelli E, Giannotti D, Collalti M, Maselli R, Genco A, Redler A, Basso N. Long-term results after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in a large monocentric series. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:757-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Braghetto I, Lanzarini E, Korn O, Valladares H, Molina JC, Henriquez A. Manometric changes of the lower esophageal sphincter after sleeve gastrectomy in obese patients. Obes Surg. 2010;20:357-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Baumann T, Grueneberger J, Pache G, Kuesters S, Marjanovic G, Kulemann B, Holzner P, Karcz-Socha I, Suesslin D, Hopt UT. Three-dimensional stomach analysis with computed tomography after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: sleeve dilation and thoracic migration. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2323-2329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Del Genio G, Tolone S, Limongelli P, Brusciano L, D’Alessandro A, Docimo G, Rossetti G, Silecchia G, Iannelli A, del Genio A. Sleeve gastrectomy and development of “de novo” gastroesophageal reflux. Obes Surg. 2014;24:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Keidar A, Appelbaum L, Schweiger C, Elazary R, Baltasar A. Dilated upper sleeve can be associated with severe postoperative gastroesophageal dysmotility and reflux. Obes Surg. 2010;20:140-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yehoshua RT, Eidelman LA, Stein M, Fichman S, Mazor A, Chen J, Bernstine H, Singer P, Dickman R, Beglaibter N. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy--volume and pressure assessment. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1083-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zayachkivska O, Bula N, Khyrivska D, Gavrilyuk E, Wallace JL. Exposure to non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and suppressing hydrogen sulfide synthesis leads to altered structure and impaired function of the oesophagus and oesophagogastric junction. Inflammopharmacology. 2015;23:91-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Penagini R, Picone A, Bianchi PA. Effect of morphine and naloxone on motor response of the human esophagus to swallowing and distension. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G675-G680. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Currier DS, Levin KR, Campbell C. Dysphagia with intrathecal fentanyl. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1570-1571. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Smiley RM, Moore RP. Loss of gag reflex and swallowing ability after administration of intrathecal fentanyl. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:1253. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Kraichely RE, Arora AS, Murray JA. Opiate-induced oesophageal dysmotility. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:601-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lalor PF, Tucker ON, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;4:33-38. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Cottam D, Qureshi FG, Mattar SG, Sharma S, Holover S, Bonanomi G, Ramanathan R, Schauer P. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an initial weight-loss procedure for high-risk patients with morbid obesity. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:859-863. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Frezza EE, Reddy S, Gee LL, Wachtel MS. Complications after sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2009;19:684-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Vilallonga R, Himpens J, van de Vrande S. Laparoscopic management of persistent strictures after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1655-1661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mui WL, Ng EK, Tsung BY, Lam CC, Yung MY. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in ethnic obese Chinese. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1571-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Burgos AM, Csendes A, Braghetto I. Gastric stenosis after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1481-1486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Dapri G, Cadière GB, Himpens J. Laparoscopic seromyotomy for long stenosis after sleeve gastrectomy with or without duodenal switch. Obes Surg. 2009;19:495-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Shabbir A, Teh JL. A New Emerging procedure - Sleeve Gastrectomy. IN: Essentials and Controversies in Bariatric Surgery. C-K Huang (Ed.). 2014;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Contival N, Gautier T, Le Roux Y, Alves A. Stenosis without stricture after sleeve gastrectomy. J Visc Surg. 2015;152:339-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Costa MN, Capela T, Seves I, Ribeiro R, Rio-Tinto R. Endoscopic Treatment of Early Gastric Obstruction After Sleeve Gastrectomy: Report of Two Cases. GE Portug J Gastroenterol. 2016;23:46-49. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lacy A, Ibarzabal A, Pando E, Adelsdorfer C, Delitala A, Corcelles R, Delgado S, Vidal J. Revisional surgery after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:351-356. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Zundel N, Hernandez JD, Galvao Neto M, Campos J. Strictures after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:154-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Stroh C, Birk D, Flade-Kuthe R, Frenken M, Herbig B, Höhne S, Köhler H, Lange V, Ludwig K, Matkowitz R. A nationwide survey on bariatric surgery in Germany--results 2005-2007. Obes Surg. 2009;19:105-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Fernández-Esparrach G, Córdova H, Bordas JM, Gómez-Molins I, Ginès A, Pellisé M, Sendino O, González-Suárez B, Cárdenas A, Balderramo D. [Endoscopic management of the complications of bariatric surgery. Experience of more than 400 interventions]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Binda A, Jaworski P, Tarnowski W. Stenosis after sleeve gastrectomy--cause, diagnosis and management strategy. Pol Przegl Chir. 2013;85:730-736. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Parikh A, Alley JB, Peterson RM, Harnisch MC, Pfluke JM, Tapper DM, Fenton SJ. Management options for symptomatic stenosis after laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy in the morbidly obese. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:738-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |