Published online Dec 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i46.10210

Peer-review started: June 22, 2016

First decision: July 29, 2016

Revised: August 25, 2016

Accepted: September 28, 2016

Article in press: September 28, 2016

Published online: December 14, 2016

Processing time: 175 Days and 1.5 Hours

To investigate the efficacy of switching to pegylated interferon-α-2a (PegIFNα-2a) treatment in nucleos(t)ide analog (NA)-treated chronic hepatitis B (CHB) responder patients.

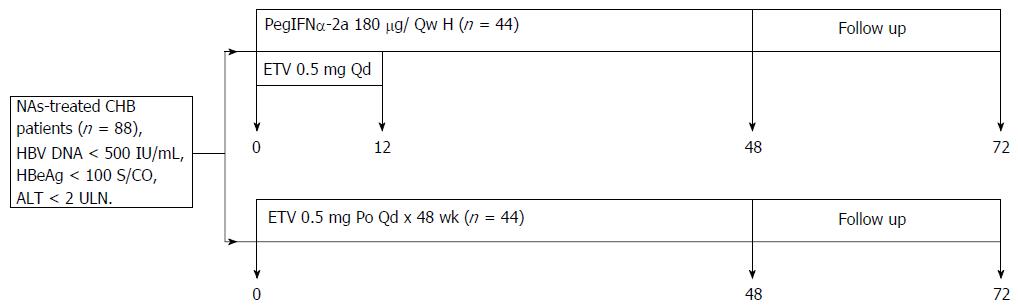

A 48-wk prospective and retrospective treatment trial of NA-treated CHB patients who had received entecavir (ETV) for at least 48 wk and had serum hepatitis B virus (HBV)-DNA < 500 IU/mL, serum hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) < 100 S/CO, serum alanine aminotransferase, and aspartate aminotransferase levels < 2 × the upper limit of normal of 40 IU/L was performed. The effects on virological and serological responses and adverse reactions to 0.5 mg daily ETV for 48 wk vs switching to PegIFNα-2a were compared. Forty-four patients were randomized to be switched from NA treatment to the PegIFNα-2a group, and 44 patients were simultaneously randomized to the ETV group.

After 48 wk of therapy, the decrease in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levels was greater in the PegIFNα-2a group than in the ETV group (3.1340 log10 IU/mL vs 3.6950 log10 IU/mL, P = 0.00). Seven patients who were anti-HBs-positive at baseline achieved HBsAg loss when switched to PegIFNα-2a (15.91% vs 0%, P = 0.018). The HBeAg serological conversion rate was higher in the PegIFNα-2a group than in the ETV group; however, the difference was not significant because of the small sample sizes (34.38% vs 21.88%, P = 0.232). In the PegIFNα-2a group, patients with HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL at baseline had higher HBeAg seroconversion and HBsAg loss rates at week 48 than those with HBsAg levels ≥ 1500 IU/mL (HBeAg seroconversion: 17.86% vs 62.5%, P = 0.007; HBsAg loss: 41.67% vs 6.25%, P = 0.016). Moreover, patients with HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL at week 24 had higher HBsAg loss rates after therapy than those with HBsAg levels ≥ 1500 IU/mL (36.84% vs 0%, P = 0.004). However, there were no statistically significant differences in HBeAg seroconversion rates (47.06% vs 25.93%, P = 0.266).

NA-treated CHB patients switched to sequential PegIFNα-2a achieved highly potent treatment termination safely.

Core tip: It is necessary to achieve termination safely with minimal risk of long-term resistance in nucleos(t)ide analog (NA)-treated chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients. We studied NA-treated CHB patients who stopped NAs safely and achieved sustained virological and immunological responses after treatment. We clarified the efficacy and safety of sequential 48-wk pegylated interferon-α-2a (PegIFNα-2a) in NA-treated CHB patients during and after treatment termination. Patients were selected based on the initial serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) level. PegIFNα-2a was adjusted based on HBsAg levels at 24 wk of treatment, an important and significant factor in achieving treatment termination safely with immune control.

- Citation: He LT, Ye XG, Zhou XY. Effect of switching from treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogs to pegylated interferon α-2a on virological and serological responses in chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(46): 10210-10218

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i46/10210.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i46.10210

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a significant clinical problem globally: it is estimated that approximately 240 million individuals are chronically infected with HBV worldwide[1]. The prevalence of HBV varies markedly among regions. China is an intermediate endemic area. According to a national epidemiological survey in China in 2006, among those aged 1-59 years, 7.18% are hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive[2]. There are approximately 100 million individuals living with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) virus infection in China, including approximately 2 million patients. Approximately 20%-30% of chronically infected persons will develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 0.65 million deaths annually are attributable to complications from hepatitis B, including cirrhosis and HCC, which are strongly associated with hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) positivity and serum HBV DNA replication[1]. Additionally, patients who are persistently HBeAg-positive are at higher risk of developing liver cirrhosis (3.5% per year)[1]. Therefore, standardized antiviral treatment is required to improve the prognosis of CHB. Current anti-HBV drugs are divided into two types. One of these is nucleoside analogs (NAs), a large class of direct antiviral drugs. In clinical practice, the duration of treatment of CHB with NAs is unclear. The role of NAs is to inhibit replication of the HBV DNA and reduce the amount of HBV in the blood to achieve therapeutic improvement. However, NAs have a single target and replace the nucleoside during HBV polymerase extension, resulting in termination of chain extension during the viral replication process, thus inhibiting viral replication[3,4]. Therefore, treatment with NAs greatly inhibits viral replication and relieves inflammation but does not eliminate the virus completely nor produces enduring HBeAg seroconversion or HBsAg clearance. Most importantly, NAs almost always produce drug resistance and relapse after discontinuation of therapy. Therefore, to reduce the risk of liver function decompensation, liver cirrhosis and HCC progression in patients with hepatitis B, a long-term antiviral treatment to inhibit HBV is required.

NAs are used widely (about 90%) in CHB treatment in China. However, not all patients are willing to continue taking NAs continuously, despite concerns regarding relapse after treatment, and hope to be able to stop taking the medicine safely. Realizing these hopes represents a tremendous challenge for NA-treated CHB patients.

Interferon (IFN) is another type of drug that has antiviral activity and acts as an immune regulator by inducing host cytokines to inhibit multiple aspects of viral replication. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)[5] has indicated that IFN therapy is the preferred treatment option for HBeAg-positive patients who achieve stable HBeAg seroconversion and for HBeAg-negative patients who achieve sustained response after therapy. An advantage of IFN is that the duration of IFN anti-HBV treatment has a clear treatment course, which is widely used for the clinical treatment of CHB. Therefore, recent research has focused on a combination therapy of IFN and NAs to exploit the antiviral and immune regulation effects of these drugs. The combination of NAs with IFN improves interferon tolerance, inhibits covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) transcription, improves the initial response rate, prevents or delays the generation of NA-resistant mutations and prevents the generation of multidrug-resistant mutations[6]. Therefore, a clinical treatment regimen with a shorter course that allows CHB patients to stop NA treatment safely might be feasible. To ensure that CHB patients who were treated with NAs can safely stop taking NAs and obtain lasting immune control, the Expert Meeting of China in 2013[7] suggested that CHB patients treated with NAs should switch to pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN) or pursue a combined treatment. NA-treated CHB patients who switch to IFN have been reported to achieve higher rates of sustained virological and serological responses than those continuing with NA monotherapy[8,9]. However, supporting medical evidence from clinical trials or clinical, real-life data are lacking.

To help NA-treated CHB patients stop NAs safely and achieve sustained virological and immunological responses after treatment, we investigated the efficacy and safety of switching NA-treated CHB patients to sequential 48-wk PegIFNα-2a by observing the virological response, HBsAg or HBeAg seroconversion rates, and other indicators.

This study was a 48-wk prospective and retrospective treatment trial comparing the efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg entecavir (ETV, Baraclude, Bristol-Myers Squibb) daily for 48 wk compared to switching to pegylated interferon alpha-2a (PegIFNα-2a, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). All patents were followed up for 24 wk (Figure 1). Patients assigned to PegIFNα-2a received 180 μg/wk for 48 wk, with the first 12 wk overlapping with 0.5 mg daily ETV. Patients assigned to the ETV group continued with ETV monotherapy. A total of 88 patients who had received ETV treatment for at least 48 wk were recruited from the Second Hospital affiliated with Guangzhou Medical University between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2015. Patients were randomized to receive PegIFNα-2a 180 μg/wk or continue 0.5 mg daily ETV for 48 wk. Eligible patients were HBsAg-positive, had serum HBV-DNA < 500 IU/mL, serum HBeAg < 100 S/CO, and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels < 2 × the upper limit of normal (ULN) of 40 IU/L. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis and HCC were excluded; as were patients co-infected with hepatitis A, C, or D; those who had been pre-treated with other antivirals; and patients with a history or evidence of other chronic liver diseases, including autoimmune hepatitis or alcohol liver disease.

HBeAg seroconversion was defined as HBeAg loss (HBeAg < 1.0 S/CO) and HBeAb positivity (HBeAb > 1.0 S/CO). HBsAg loss was defined as HBsAg < 0.05 IU/L. HBsAg seroconversion was defined as HBsAg loss and HBsAb positivity (HBsAb >10.0 IU/L).

Clinical examination and routine laboratory tests were performed at the beginning of therapy, at 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 wk during antiviral therapy and at follow-up at 12 and 24 wk after therapy. Biochemical [serum AST, ALT, creatinine (Cr), and glucose (Glu)] and virological parameters (HBeAg, HBAb, HBcAb status and HBV DNA levels) were measured at each visit. Serum HBV DNA was detected using either a standard generic HBV DNA assay (Da An Gene, normal level of HBV DNA < 500 IU/mL) or the COBAS TaqMan HBV Test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA, United States). HBeAg, HBeAb, HBcAb status was detected using chemiluminescence measurements. The laboratory technicians were unaware of the trial. The PegIFNα-2a group was divided into an HBsAg < 1500 IU/mL group and an HBsAg ≥ 1500 IU/mL group based on the HBsAg level at baseline and after 24 wk of therapy.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 13.0 software. Quantitative data were analyzed by a t-test or non-parametric Wilcoxon test as appropriate, and qualitative data were analyzed by Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test.

There were 88 patients in the trial (PegIFNα-2a, n = 44; ETV, n = 44), and all patients accepted the regular 48 wk of treatment and 24 wk of follow-up. The mean age was 35.41 years (95%CI: 32.68-39.03) in the PegIFNα-2a group and 35.43 years (95%CI: 32.42-38.43) in the ETV group. There were no statistically significant differences in age, gender or serum biochemical data between the two groups (Table 1).

| PegIFNα-2a | ETV | P value | |

| Age (yr), mean | 35.41 (95%CI: 32.68-39.03) | 35.43 (95%CI: 32.42-38.43) | 0.8321 |

| Male | 62.86% | 68.57% | 0.6152 |

| ALT (U/L), mean | 34.60 (95%CI: 30.31-38.89) | 33.06 (95%CI: 30.15-35.96) | 0.7451 |

| HBsAg (IU/mL), mean | 6168.8630 (95%CI: 3841.12-8496.60) | 5879.4557(95%CI: 3643.06-8115.85) | 0.9601 |

| HBeAg (+) | 29/44 (65.91%) | (27/44) 61.36% | 0.6582 |

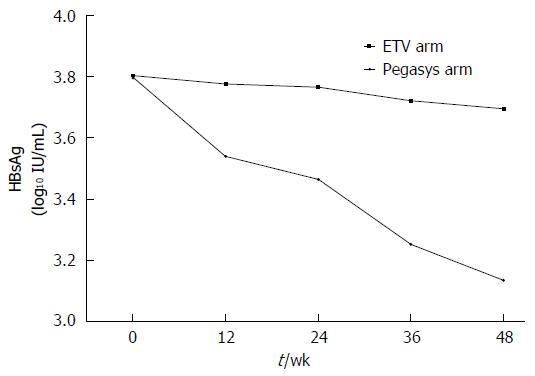

HBsAg levels in patients in the PegIFNα-2a group (Figure 2): During therapy, HBsAg levels were 3.7902, 3.5405, 3.4661, 3.2511, and 3.1340 log10 IU/mL at baseline and weeks 12, 24, 36, and 48 of therapy, respectively. However, the changes were small in the ETV group. After 48 wk of therapy, the decrease in HBsAg levels was greater in the PegIFNα-2a group than in the ETV group (3.1340 log10 IU/mL vs 3.6950 log10 IU/mL, P = 0.00, Table 2).

Serological response (Table 2): In the PegIFNα-2a group, seven of the 44 patients achieved HBsAg loss, and one patient exhibited HBsAg seroconversion. By contrast, no patients in the ETV group achieved HBsAg loss or HBsAg seroconversion after 48 wk of therapy. More patients attained HBsAg loss in the PegIFNα-2a group (15.91%) than in the ETV monotherapy group (15.91% vs 0%, P = 0.018). There were five and two individuals who remained HBeAg-positive and -negative at baseline, respectively. During the NA treatment period, both the PegIFNα-2a and ETV groups experienced HBeAg seroconversion. The HBeAg serological conversion rate was higher in the PegIFNα-2a group than in the ETV group, although the difference was not significant because of the small sample sizes (34.38% vs 21.88%, P = 0.232).

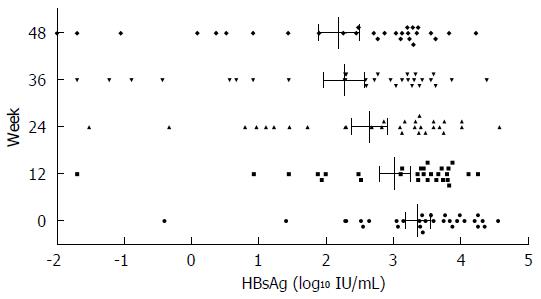

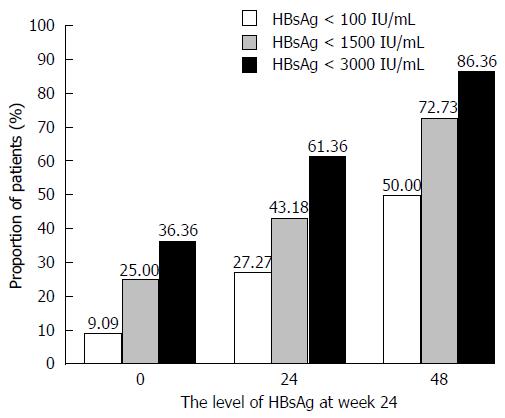

As the treatment time increased, the decrease in HBsAg levels became more obvious. Significantly more patients (Figures 3 and 4) in the PegIFNα-2a group had HBsAg levels of <100 IU/mL after treatment than before treatment (50.00% vs 9.09%, P = 0.00). Among patients with HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL, the percent changes were 72.73% vs 25.00%, P = 0.00, and in patients with HBsAg levels < 3000 IU/mL, the percent changes were 86.36% vs 36.36%, P = 0.00.

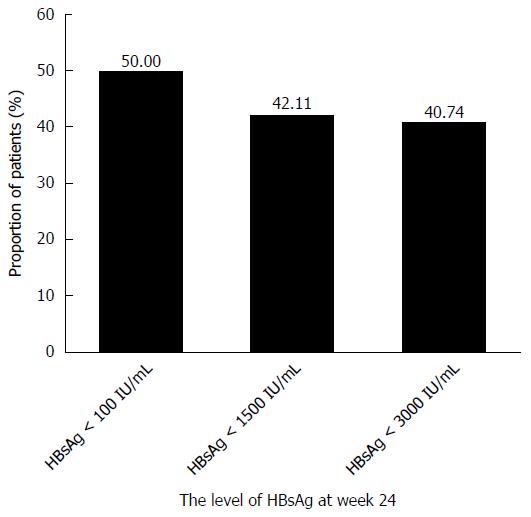

Early HBsAg decline predicted the response at week 48. The highest rates of HBeAg seroconversion and HBsAg loss were observed in patients with an HBsAg level < 100 IU/mL at week 24 (Figures 5 and 6). In the PegIFNα-2a group, patients with an HBsAg level < 100 IU/mL, an HBsAg level < 1500 IU/mL, or an HBsAg level < 3000 IU/mL achieved 50%, 42.2%, and 40.74% HBeAg seroconversion at week 48, respectively.

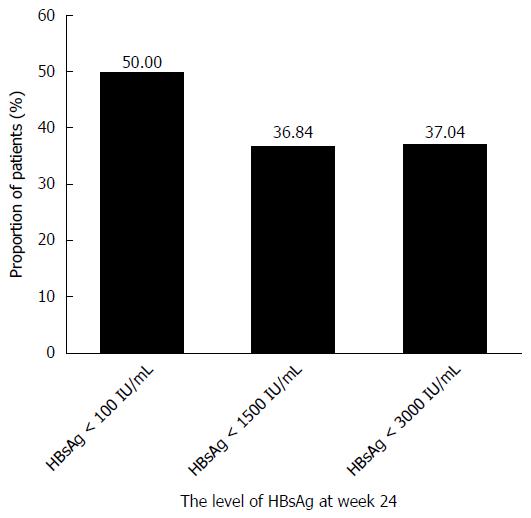

In the PegIFNα-2a group, patients with an HBsAg level < 100 IU/mL, an HBsAg level < 1500 IU/mL, or an HBsAg level < 3000 IU/mL achieved 50%, 36.84% and 25.93% HBsAg loss at week 48, respectively.

In the PegIFNα-2a group, patients with an HBsAg level < 1500 IU/mL at baseline had higher HBeAg seroconversion and HBsAg loss rates at week 48 compared with those with an HBsAg level ≥ 1500 IU/mL (HBeAg seroconversion: 62.5% vs 17.86%, P < 0.05; HBsAg loss: 41.67% vs 6.25%, P < 0.05). Moreover, those with an HBsAg level < 1500 IU/mL at week 24 had higher HBsAg loss rates after therapy compared with those with an HBsAg level ≥ 1500 IU/mL (36.84% vs 0%, P < 0.05). However, the differences in HBeAg seroconversion between the groups were not significant (47.06% vs 25.93%, P > 0.05) (Table 3).

| HBsAg loss at week 48 | HBeAg seroconversion at week 48 | |||

| n | P value | n | P value | |

| HBsAg level < 1500 IU/mL at baseline | 5/12 (41.67%) | 0.0161 | 10/16 (62.5%) | 0.0071 |

| HBsAg level ≥ 1500 IU/mL at baseline | 2/32 (6.25%) | 5/28 (17.86%) | ||

| HBeAg-positive at baseline | 5/29 (17.24%) | 1.0001 | - | - |

| HBeAg-negative at baseline | 2/15 (13.33%) | - | ||

| HBsAg level < 1500 IU/mL at week 24 | 7/19 (36.84%) | 0.0041 | 8/17 (47.06%) | 0.2661 |

| HBsAg level ≥ 1500 IU/mL at week 24 | 0/25 (0) | 7/27 (25.93%) | ||

During the 24-wk follow-up, all the patients who switched to PegIFNα-2a maintained HBV-DNA negative status and normal serum AST and ALT.

Thirty-five patients, including two who were HBeAg-positive after 48 wk of treatment with PegIFNα-2a, experienced HBeAg seroconversion during 24 wk of follow-up. The cumulative HBeAg seroconversion rate was 41.46%, whereas no patients achieved HBeAg seroconversion in the ETV group. However, the difference between the groups was not significant (41.46% vs 21.95%, P = 0.058).

The HBsAg level of one patient who lost HBsAg with PegIFNα-2a treatment for 48 wk was 0.67 IU/mL at the 24th wk of follow-up, even though the patient maintained HBeAg seroconversion, HBV-DNA negative status and normal serum ALT and AST.

One patient who received PegIFNα-2a developed a complication of hyperthyroidism during week 39, and the patient was not discontinued due to methimazole treatment.

Adverse events, including headache, dry mouth, weakness and decreases in leucocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets, occurred in the majority of patients. One of the 35 patients in the PegIFNα-2a group had these adverse events, which were mild and had no effect on treatment progress. However, a minority of patients in the ETV group had the above-mentioned adverse events.

In our study, regardless of the baseline levels or HBeAg positivity or negativity of the two groups of CHB patients, HBV DNA was fully suppressed by 1-5 years of NA treatment. Despite this suppression, these patients remained HBeAg-positive, albeit at lower levels. Compared with ETV monotherapy, the addition of PegIFNα-2a for 48 wk, based on HBsAg-titer monitoring produced higher HBeAg seroconversion, greatly decreased HBsAg levels, and achieved HBsAg loss and even HBsAg seroconversion with no relapse after 24 wk of follow-up. These results are similar to Ouzan’s report[10].

The NEPTUNE study[11] indicated that 14% of patients treated with PegIFN for one year had deferred HBeAg seroconversion, and 86% of the patients achieved HBeAg seroconversion during the therapy. In this study, the rate of HBeAg seroconversion was 21.95%, which lower than the rate after PegIFNα-2a treatment (36.59% vs 21.95%, P = 0.145). This result is consistent with previous research[12] on ETV monotherapy. Moreover, we observed that PegIFNα-2a was effective even after treatment was terminated. The OSST study[9] confirmed higher HBeAg seroconversion rates in the PegIFNα-2a group compared with the ETV group (14.9% vs 6.1%, P = 0.0467). The differences in HBeAg seroconversion between the two groups were not significant, possibly because of the small sample size in our study.

HBsAg loss is considered the ultimate long-term goal of antiviral therapy by the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver, EASL, and the American Association for the Study of the Liver[5,13,14]. However, achieving HBsAg loss and sustained virological and serological responses is difficult with general treatment using NAs. The median number of years of NA treatment required for HBsAg loss is 52.2 years (interquartile range: 30.8-142.7)[15]. In our study, 50% of patients exhibited a reduction of HBsAg levels to less than 100 IU/mL after PegIFNα-2a therapy, and 86.36% of patients had HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL. The level of serum HBsAg was predominantly and closely associated with intrahepatic cccDNA levels[16]. HBsAg levels < 100 IU/mL at the end of the treatment indicated a sustained response to NA-induced HBeAg seroconversion[17]. At the 3-year post-treatment follow-up, 52% of the patients with HBsAg levels < 10 IU/mL at the end of treatment achieved HBsAg loss[18]. Moreover, IFN has both antiviral and immunomodulatory effects, and thus decreases the amount of cells containing the HBV intrahepatic cccDNA molecule, which is required for sustained, chronic HBV infection[6]. Therefore, patients switching to PegIFNα-2a might achieve permanent HBeAg seroconversion and even achieve HBsAg loss to reach the ideal endpoint of therapy. Experts have suggested that to resolve long-term medication problems, and achieve higher HBeAg seroconversion, HBsAg loss and sustained response after treatment termination, NA-treated CHB patients should receive the combination therapy or switch to PegINF[7].

Shouval et al[19] demonstrated that after 48 wk of ETV treatment alone and 24 wk of follow-up, the virological relapse rate was 97%, and 39% of patients had serum ALT of less than 1 × ULN. Additionally, Seto et al[20] indicated that after 24 and 48 wk of entecavir treatment, 74.2% and 91.4% of patients suffered recurrent viremia. Chaung et al[21] reported that 90% of patients experienced virological relapse once they discontinued NA therapy. In the present study, during the 24-wk follow-up, none of the patients who switched to PegIFNα-2a became HBV-DNA positive or had abnormal serum AST or ALT.

During the follow-up period, one of the patients in the PegIFNα-2a group who exhibited HBsAg loss at the end of the 48 wk of treatment became HBsAg-positive and exhibited an increased level of HBsAg. During the 24-wk follow-up period, this patient maintained normal hepatic function, and the level of HBV-DNA was below the detection limit of 0.67 IU/mL cccDNA remaining in the liver cells of patients who undergo HBsAg loss[22]. Additionally, in HBsAg-loss patients, the median interval between HBV DNA measurements was 48 mo. The viral load in the extrahepatic reservoir decreases with time[22]. Therefore, we considered the patient to be at a persistent low HBsAg level and closely monitored the patient’s liver function and HBV DNA levels.

HBeAg seroconversion and lower HBsAg levels can reduce the incidence of liver cirrhosis and liver cancer[23,24]. Compared with ETV monotherapy, PegIFNα-2a not only increased the serological conversion rate, but also produced an ideal effect after treatment termination, which has a persistent influence on the immune function of patients who achieved HBeAg seroconversion. Additionally, IFN prevents the formation of HBV proteins and depletes the intrahepatic cccDNA pool, which results in further HBsAg loss compared with ETV alone[10].

Therefore, the results indicated that the application of PegIFNα-2a induces a strong cccDNA decline and low serum levels of HBsAg, thus reducing the relapse rate of CHB patients after treatment termination and improving immune control and safe treatment termination.

Santantonio et al[25] and Marcellin et al[26] reported that HBsAg loss and seroconversion rates did not differ significantly between lamivudine monotherapy and combined PegIFNα-2a therapy in patients who were HBeAg-negative. Janssen et al[27] also indicated that HBeAg loss or seroconversion rates were similar after lamivudine monotherapy and combined PegIFNα-2a therapy in HBeAg-positive patients. However, these reports did not focus on NA-treated CHB patients. Therefore, additional clinical cases must be analyzed to determine if INF monotherapy directly, or the combined NA and interferon treatment, is superior for NA-treated CHB patients.

The level of HBsAg in the patients who were HBeAg-negative or HBeAg-positive was not related to the curative effect in the PegIFNα-2a group (P > 0.05). The lower the HBsAg level at baseline, the higher the HBeAg seroconversion and HBsAg loss rates at week 48. We speculated that the efficacy of 48 wk of treatment based on HBsAg levels at the 24th wk of therapy would produce a HBsAg loss rate of up to 36.84% (P < 0.05) in patients with a serum HBsAg level < 1500 IU/mL, and the efficacy was not determined by HBeAg seroconversion (P > 0.05).

The HBsAg loss rate of the patients with serum HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL in our trial was obviously higher than that observed in the OSST study[9] (44.44% vs 25%), which may be related to the lower baseline HBV DNA levels (< 500 IU/mL) and longer ETV combination to ensure persistent virus inhibition. There are no unified clinical recommendations on how long NAs and PegIFNα-2a therapy should administered. The benefits of prolonged treatment with ETV or extended PegIFNα-2a treatment in patients with higher serum HBsAg levels at baseline require further clinical observation.

This study has some limitations, such as the small sample size, which prevented deeper analysis of the relationship between HBsAg levels and curative effect after 48 wk of therapy. CHB is a chronic disease; therefore, the follow-up period of only 24 wk was relatively short. The prognosis of patients requires longer follow-up times and further observation.

In conclusion, brief treatment of NA-treated CHB patients with a combination of NAs and PegIFNα-2a could achieve highly potent treatment termination safely, with a minimal risk of long-term resistance. Based on the initial serum HBsAg level in NA-treated CHB patients, we could select superior patients to switch to PegIFNα-2a and, according to the levels of HBsAg at 24 wk of treatment, adjust the treatment to continue with PegIFNα-2a or switch to NAs. This protocol has an important and significant effect on achieving treatment termination safely and with immune control.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a significant clinical problem globally: it is estimated that approximately 240 million individuals are chronically infected with HBV worldwide. Therefore, standardized antiviral treatment, including nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) and interferon (IFN) is required to improve the prognosis of chronic hepatitis B (CHB). NA-treated CHB patients who switch to IFN have been reported to achieve higher rates of sustained virological and serological responses than those continuing with NA monotherapy. However, supporting medical evidence from clinical trials or clinical, real-life data are lacking.

Recent research has focused on combination therapy with IFN and NAs to exploit the antiviral and immune regulation effects of these drugs. However, there are very few clinical studies about this combination worldwide, especially in China. This research investigated the efficacy of switching to IFN in NA-treated CHB patients.

NAs are used widely in CHB treatment in China. Not all patients are willing to continue taking NAs continuously. The European Association for the Study of the Liver indicated that IFN therapy is the preferred treatment option for CHB patients who achieve a sustained response after therapy. This research focused on the efficacy of a combination therapy with IFN and NAs. The authors analyzed different monitoring methods for NA-treated CHB patients switching to IFN, which has an important and significant effect on choosing suitable patients and estimating the risk of long-term resistance in treatment termination.

Medical evidence from clinical trials helps clinicians choose different types of standardized antiviral treatment for different CHB patients. The present research showed that brief treatment of NA-treated CHB patients with a combination of NAs and pegylated interferon-α-2a (PegIFNα-2a) could achieve highly potent treatment termination safely, with a minimal risk of long-term resistance.

Currently, standardized antiviral treatment includes nucleoside NAs and IFN. Treatment of CHB has a clear treatment course with IFN. However, CHB patients need to take NA for a long and undefined time because NAs cannot eliminate the virus completely. CHB patients treated with Entecavir (ETV) have a chance of HBeAg seroconversion at least 48 wk and show decreased serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels. However, ETV cannot decrease the HBsAg level nor sustain virological and serological responses after therapy, luckily, IFN helps to fill this gap.

In this paper, the authors investigated the efficacy and safety of switching CHB patients successfully treated with Entecavir to PegIFNα-2a NA-treated. The topic is of great interest. In fact, in recent years several attempts have been performed to transform a “long-life” treatment with NAs to a treatment of a “finite” duration. The paper is well written and can be considered for publication after minor revisions.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Santantonio TA S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Liu WX

| 1. | WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Guidelines for the Prevention, Care and Treatment of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis B Infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015; . [PubMed] |

| 2. | Hou JL, lai W. [The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B: a 2015 update]. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2015;23:888-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yokosuka O, Takaguchi K, Fujioka S, Shindo M, Chayama K, Kobashi H, Hayashi N, Sato C, Kiyosawa K, Tanikawa K. Long-term use of entecavir in nucleoside-naïve Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 2010;52:791-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yuen MF, Seto WK, Chow DH, Tsui K, Wong DK, Ngai VW, Wong BC, Fung J, Yuen JC, Lai CL. Long-term lamivudine therapy reduces the risk of long-term complications of chronic hepatitis B infection even in patients without advanced disease. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:1295-1303. [PubMed] |

| 5. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2400] [Article Influence: 184.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wursthorn K, Lutgehetmann M, Dandri M, Volz T, Buggisch P, Zollner B, Longerich T, Schirmacher P, Metzler F, Zankel M. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus adefovir induce strong cccDNA decline and HBsAg reduction in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:675-684. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Expert guoup on treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B who have an initial nucleotide(s)analogue therapy with pegylated interferon α. Expert opinion on the treatment of the NUCs-treated chronic hepatitis B patients treated with interferon alpha. Zhongguo Ganzangbingxue Zazhi. 2013;21:494-497. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Bonino F, Marcellin P, Lau GK, Hadziyannis S, Jin R, Piratvisuth T, Germanidis G, Yurdaydin C, Diago M, Gurel S. Predicting response to peginterferon alpha-2a, lamivudine and the two combined for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2007;56:699-705. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ning Q, Han M, Sun Y, Jiang J, Tan D, Hou J, Tang H, Sheng J, Zhao M. Switching from entecavir to PegIFN alfa-2a in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomised open-label trial (OSST trial). J Hepatol. 2014;61:777-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ouzan D, Pénaranda G, Joly H, Khiri H, Pironti A, Halfon P. Add-on peg-interferon leads to loss of HBsAg in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis and HBV DNA fully suppressed by long-term nucleotide analogs. J Clin Virol. 2013;58:713-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chan HL, Leung NW, Hui AY, Wong VW, Liew CT, Chim AM, Chan FK, Hung LC, Lee YT, Tam JS. A randomized, controlled trial of combination therapy for chronic hepatitis B: comparing pegylated interferon-alpha2b and lamivudine with lamivudine alone. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:240-250. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, Lok AS, Han KH, Goodman Z, Zhu J. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001-1010. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Chan HL, Chien RN, Liu CJ, Gane E, Locarnini S, Lim SG, Han KH. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 742] [Cited by in RCA: 792] [Article Influence: 60.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2170] [Article Influence: 135.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chevaliez S, Hézode C, Bahrami S, Grare M, Pawlotsky JM. Long-term hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) kinetics during nucleoside/nucleotide analogue therapy: finite treatment duration unlikely. J Hepatol. 2013;58:676-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thompson AJ, Nguyen T, Iser D, Ayres A, Jackson K, Littlejohn M, Slavin J, Bowden S, Gane EJ, Abbott W. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B e antigen titers: disease phase influences correlation with viral load and intrahepatic hepatitis B virus markers. Hepatology. 2010;51:1933-1944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chan HL, Wong GL, Chim AM, Chan HY, Chu SH, Wong VW. Prediction of off-treatment response to lamivudine by serum hepatitis B surface antigen quantification in hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:1249-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Brunetto MR, Moriconi F, Bonino F, Lau GK, Farci P, Yurdaydin C, Piratvisuth T, Luo K, Wang Y, Hadziyannis S. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen levels: a guide to sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:1141-1150. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Shouval D, Lai CL, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Martin P, Carosi G, Han S, Kaymakoglu S, Tamez R, Yang J. Relapse of hepatitis B in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients who discontinued successful entecavir treatment: the case for continuous antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2009;50:289-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seto WK, Hui AJ, Wong VW, Wong GL, Liu KS, Lai CL, Yuen MF, Chan HL. Treatment cessation of entecavir in Asian patients with hepatitis B e antigen negative chronic hepatitis B: a multicentre prospective study. Gut. 2014;64:667-672. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Chaung KT, Ha NB, Trinh HN, Garcia RT, Nguyen HA, Nguyen KK, Garcia G, Ahmed A, Keeffe EB, Nguyen MH. High frequency of recurrent viremia after hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion and consolidation therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:865-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Werle-Lapostolle B, Bowden S, Locarnini S, Wursthorn K, Petersen J, Lau G, Trepo C, Marcellin P, Goodman Z, Delaney WE. Persistence of cccDNA during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B and decline during adefovir dipivoxil therapy. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1750-1758. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Martinot-Peignoux M, Carvalho-Filho R, Lapalus M, Netto-Cardoso AC, Lada O, Batrla R, Krause F, Asselah T, Marcellin P. Hepatitis B surface antigen serum level is associated with fibrosis severity in treatment-naïve, e antigen-positive patients. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1089-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Liu WR, Tian MX, Jin L, Yang LX, Ding ZB, Shen YH, Peng YF, Zhou J, Qiu SJ, Dai Z. High levels of hepatitis B surface antigen are associated with poorer survival and early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with low hepatitis B viral loads. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:843-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Santantonio T, Niro GA, Sinisi E, Leandro G, Insalata M, Guastadisegni A, Facciorusso D, Gravinese E, Andriulli A, Pastore G. Lamivudine/interferon combination therapy in anti-HBe positive chronic hepatitis B patients: a controlled pilot study. J Hepatol. 2002;36:799-804. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, Farci P, Hadziyannis S, Jin R, Lu ZM, Piratvisuth T, Germanidis G, Yurdaydin C. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1206-1217. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Sonneveld MJ, Rijckborst V, Boucher CA, Hansen BE, Janssen HL. Prediction of sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2b for hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B using on-treatment hepatitis B surface antigen decline. Hepatology. 2010;52:1251-1257. [PubMed] |