Published online Dec 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i46.10198

Peer-review started: July 26, 2016

First decision: September 20, 2016

Revised: October 25, 2016

Accepted: November 14, 2016

Article in press: November 16, 2016

Published online: December 14, 2016

Processing time: 141 Days and 8.9 Hours

To evaluate the prevalence of nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH) in adult patients undergoing colonoscopy and its association with known diseases.

We selected all cases showing NLH at colonoscopy in a three-year timeframe, and stratified them into symptomatic patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-type symptoms or suspected inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and asymptomatic individuals undergoing endoscopy for colorectal cancer screening. Data collection included medical history and final diagnosis. As controls, we considered all colonoscopies performed for the aforementioned indications during the same period.

One thousand and one hundred fifty colonoscopies were selected. NLH was rare in asymptomatic individuals (only 3%), while it was significantly more prevalent in symptomatic cases (32%). Among organic conditions associated with NLH, the most frequent was IBD, followed by infections and diverticular disease. Interestingly, 31% of IBS patients presented diffuse colonic NLH. NLH cases shared some distinctive clinical features among IBS patients: they were younger, more often female, and had a higher frequency of abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhoea, unspecific inflammation, self-reported lactose intolerance and metal contact dermatitis.

About 1/3 of patients with IBS-type symptoms or suspected IBD presented diffuse colonic NLH, which could be a marker of low-grade inflammation in a conspicuous subset of IBS patients.

Core tip: This study sheds light on colonic nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH) in terms of prevalence, gender-distribution and association with known diseases. Our most relevant result is the identification of NLH as a putative marker of low-grade inflammation in a conspicuous subset of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) cases. Further studies are required to understand the etiopathogenetic mechanisms underlying NLH in IBS, its association with metal contact allergies and its clinical implications.

- Citation: Piscaglia AC, Laterza L, Cesario V, Gerardi V, Landi R, Lopetuso LR, Calò G, Fabbretti G, Brisigotti M, Stefanelli ML, Gasbarrini A. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia: A marker of low-grade inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome? World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(46): 10198-10209

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i46/10198.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i46.10198

Colonoscopy allows direct visualization of the mucosa of the lower gastrointestinal tract and it is a useful tool to investigate symptoms of lower bowel diseases. However, there are conditions in which symptomatic patients might have a normal colon appearance on colonoscopy, although their intestinal mucosa shows signs of microscopic inflammation at histological examination[1]. In the last years, the introduction of advanced imaging techniques has ameliorated the characterization of mucosal lesions and has permitted to detect minimal mucosal changes that might be missed with standard white-light (WL) colonoscopy[2]. Among such techniques, narrow band imaging (NBI) uses optical filters in front of the light source, to narrow the wavelength of the projected light, to enable visualization of micro-vessel morphological changes and to enhance the visibility of both neoplastic and inflammatory mucosal lesions[3,4].

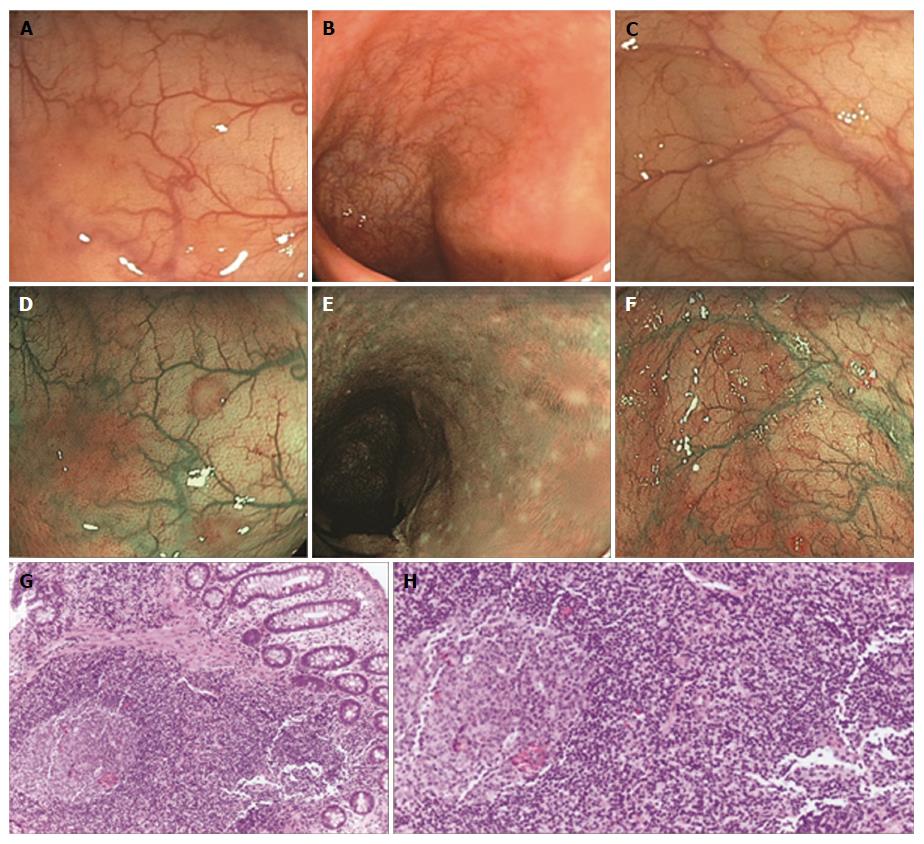

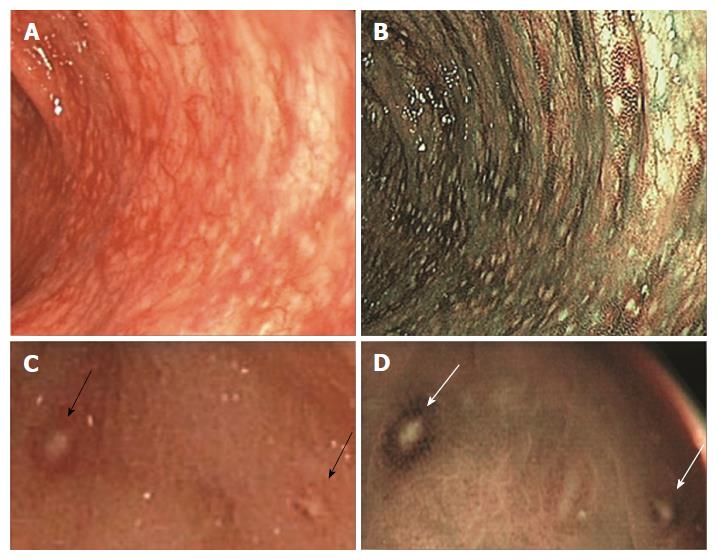

In our daily practice, we have noted that some patients undergoing colonoscopy showed multiple slightly raised whitish areas, usually < 5 mm in diameter, closely spaced, difficult to see at WL endoscopy and easier to recognize with NBI. When biopsied, these areas always corresponded to clusters of ≤ 10 lymphoid nodules, composed of hyperplastic benign lymphoid tissue, named “nodular lymphoid hyperplasia” (NLH)[5-9]. Sometimes NLH had a reddish outline, the so-called “red ring sign” (RRS), due to hypervascularization at the base of the follicles, associated with granulocyte infiltrate[6].

Little is known about the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical implications of NLH. NLH is commonly seen in the terminal ileum and colon during paediatric endoscopies, and it has been classically considered a paraphysiologic phenomenon in children[10]. However, there have been reports of NLH in children associated with refractory constipation, viral infection, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, connective tissue disease, immunodeficiency, cow’s milk protein hypersensitivity, familial mediterranean fever, and the so-called “autistic enterocolitis”[9,11-18].

In adults, NLH can be asymptomatic, or more rarely presents with gastrointestinal symptoms, like abdominal pain, chronic diarrhoea, and bleeding[18]. NLH can mimic familial polyposis[19,20] and it has been reported in association with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease (CeD), lymphoma, dysgammaglobulinemia, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, diversion colitis and food allergies[21-28].

Adult NLH is considered a rare finding[29]. Published literature includes case reports and small series of patients; whether this relates to endoscopy underreporting or to the true rarity of the condition is unclear[30]. Indeed, NLH frequency in adults might be largely underestimated because it is hard to recognize at WL endoscopy. Kagueyama et al[31], demonstrated that 39% of adult patients with chronic diarrhoea and a normal colonoscopy had NLH at histological examination of serial biopsies taken from the terminal ileum, ascending colon and rectum. In 2010, Krauss et al[6] evaluated the significance of lymphoid hyperplasia in the lower gastrointestinal tract in a cohort of consecutive adult patients and concluded that the presence of colonic NLH is not rare and it may represent a mucosal response to antigenic stimulation, like allergens or pathogens.

Most of the NLH cases that we have found in our daily practice, underwent colonoscopy for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-type symptoms, or suspected IBD, while a minority of them was asymptomatic. Based on this clinical observation, the aim of the present study is to evaluate the prevalence of NLH in adults undergoing colonoscopy in San Marino Republic, and its association with known diseases.

We evaluated all colonoscopies performed by a single endoscopist (ACP) from January 2012 to January 2015, at the Endoscopy Unit of the State Hospital of San Marino Republic.

We selected all cases showing lesions compatible with NLH, for which biopsies from multiple sites (ileum, ascending, transverse, sigmoid colon, and rectum) were taken. NLH cases were divided into two groups: asymptomatic subjects (a-NLH), who underwent colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening or family history of colorectal cancer; and symptomatic patients (s-NLH), in which colonoscopy was prescribed for IBS-type symptoms (abdominal pain and/or altered bowel habits in the absence of alarm signs or symptoms) or suspected IBD [abdominal pain and/or altered bowel habits with haematochezia and/or weight loss and/or positive family history of IBD and/or fever and/or increased faecal calprotectin and/or C-reactive protein, and/or anaemia]. Symptomatic patients were further divided according to their final diagnosis into organic and functional bowel disorders; the latter subset was stratified into IBS [with prevalent diarrhoea (IBS-D), or constipation (IBS-C), or mixed bowel habit (IBS-M)], chronic functional diarrhoea and chronic constipation[32].

In order to measure the prevalence of NLH in asymptomatic subjects and symptomatic patients, we considered all colonoscopies performed by the same endoscopist for the same clinical indications (colorectal cancer screening, IBS-type symptoms, suspected IBD), in the same timeframe (January 2012 to January 2015).

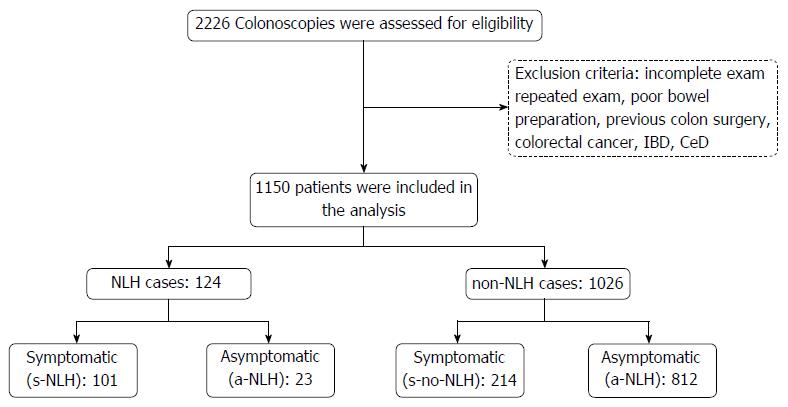

In case of repeated colonoscopies on the same patient, only the first examination was included in the analysis. Other exclusion criteria were incomplete exam, poor bowel preparation, patient’s age < 18 or > 75 years, history of colon surgery, prior diagnosis of colorectal cancer, IBD, or CeD.

The study protocol was approved by the local Ethical Committee and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

All colonoscopies were performed under deep sedation with Midazolam and Propofol, with anaesthesiologist’s assistance. For bowel preparation, all patients received low-volume polyethylenglycol-based medication (Lovol Esse®). NLH was macroscopically evaluated using Olympus endoscopes CF-HQ190 (for EVIS EXERA III Video System Center CV-190) or CF-Q180A (for EXERA II Video System Center CV-180), in white light and NBI.

Biopsies were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Four-µm tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and evaluated by two expert pathologists (Fabbretti G, Brisigotti M). Each tissue section was observed on light microscopy using × 20 objective lenses and × 10 eyepiece.

We reviewed patients’ charts to investigate about bowel habits, self-reported lactose intolerance, metal contact dermatitis, histological confirmation of NLH and final diagnosis.

Data were collected in an Excel database. Summary statistics were calculated for each outcome of interest. Continuous data were summarized with mean and standard deviation, while categorical data were summarized with frequency distributions. We used t-test and χ2 test to compare patients’ subgroups. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was generated using Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, United States) and Real Statistics Resource Pack software (Release 3.5; Copyright 2013-2015 Charles Zaiontz; http://www.real-statistics.com).

Figure 1 summarizes the study design. 2226 colonoscopies were assessed for eligibility. Of those, 1076 met the exclusion criteria and were ruled out. NLH was observed in 124 of the 1150 cases under analysis (global NLH prevalence about 10%). Of note, NLH was found in 101 of 315 symptomatic patients (32%) and in only 23 of 835 asymptomatic subjects (3%).

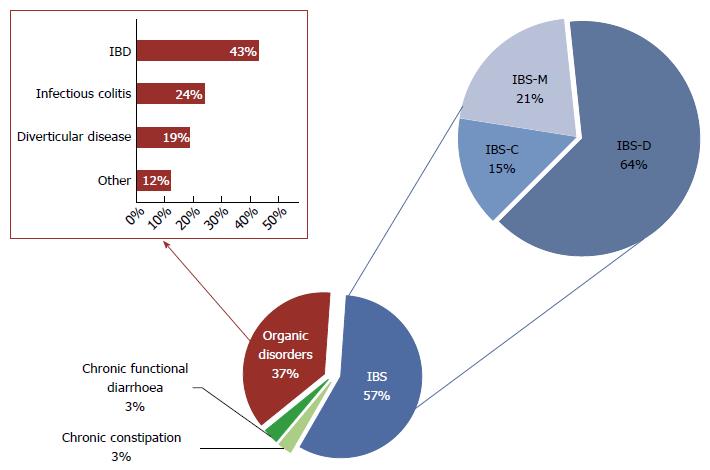

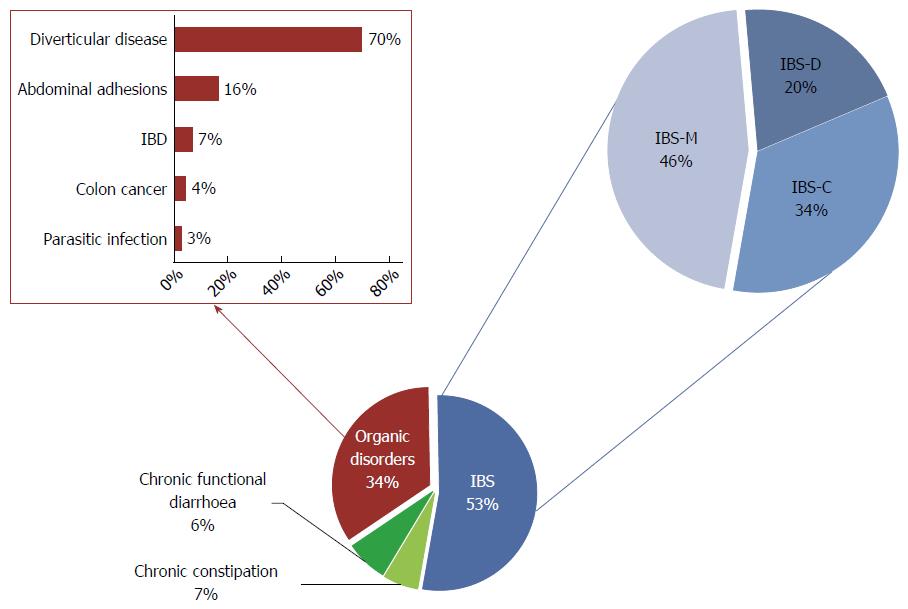

The main symptomatic patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Collectively, out of 315 symptomatic patients, 110 were diagnosed with organic disorders (35%), whereas the remaining 65% had functional disease. NLH was found in 32% of symptomatic patients and it was always histologically confirmed (Figure 2). NLH was equally distributed among organic (34%) and functional (31%) conditions.

| All patients | s-NLH | s-no-NLH | p (s-NLH vs s-no-NLH) | ||||||||

| s-NLH | s-no-NLH | p (s-NLH vs s-no-NLH) | F | O | p (F vs O) | F | O | p (F vs O) | F | O | |

| Average years of age (mean ± SD) | 41 ± 14 | 53 ± 12 | < 0.051 | 40 ± 13 | 42 ± 16 | NS1 | 49 ± 12 | 60 ± 10 | < 0.051 | < 0.051 | < 0.051 |

| Female sex | 85% | 68% | NS2 | 92% | 73% | < 0.052 | 70% | 64% | NS2 | < 0.052 | NS2 |

| Abdominal pain | 91% | 83% | NS2 | 91% | 92% | NS2 | 80% | 89% | NS2 | < 0.052 | NS2 |

| Bloating | 72% | 37% | < 0.052 | 78% | 63% | NS2 | 30% | 49% | < 0.052 | < 0.052 | NS2 |

| Diarrhoea | 65% | 26% | < 0.052 | 63% | 70% | NS2 | 26% | 26% | NS2 | < 0.052 | < 0.052 |

| Constipation | 17% | 36% | < 0.052 | 19% | 14% | NS2 | 38% | 34% | NS2 | < 0.052 | < 0.052 |

| Mixed bowel habits | 18% | 34% | NS2 | 19% | 16% | NS2 | 37% | 27% | NS2 | < 0.052 | NS2 |

| Polyps | 24% | 45% | < 0.052 | 23% | 24% | NS2 | 42% | 52% | NS2 | < 0.052 | < 0.052 |

| Haematochezia | 23% | 40% | NS2 | 18% | 32% | NS2 | 41% | 37% | NS2 | < 0.052 | NS2 |

| Inflammation | 45% | 28% | NS2 | 39% | 54% | < 0.052 | 16% | 49% | < 0.052 | < 0.052 | NS2 |

| Metal contact dermatitis | 74% | 6% | < 0.052 | 66% | 77% | NS2 | 7% | 5% | NS2 | < 0.052 | < 0.052 |

| Lactose intolerance | 63% | 28% | < 0.052 | 38% | 77% | < 0.052 | 26% | 32% | NS2 | < 0.052 | < 0.052 |

In most symptomatic patients with NLH (s-NLH) cases, NLH was present in all colonic segments (94%); 21% of patients also showed NLH in the terminal ileum; NLH was observed in the right or left colon alone in 1% and 5% of cases, respectively.

As for clinical presentation, all s-NLH patients complained of altered bowel habits, mainly chronic diarrhoea; most cases also reported abdominal pain and bloating; 23% had haematochezia. In 39% of patients, colonoscopy revealed concomitant macroscopic inflammation (RRS, diffuse hyperaemia, erosions, and ulcers); in 69% of cases, the inflammation was patchy and confined to the left colon and/or rectum; a patchy right-sided colitis was observed in 5% of s-NLH patients; in 8% of cases, the inflammation involved the terminal ileum. Colon polyps were found and removed in 21% of s-NLH patients.

A history of delayed hypersensitivity reactions and in particular of metal contact dermatitis was self-reported by 74% of s-NLH patients, but only a minority of them (9%) had a previous patch test-based diagnosis of nickel (Ni) allergy. Moreover, 63% of patients with NLH self-reported lactose intolerance.

The final diagnosis for s-NLH was of organic disease in 37% of cases and of functional disorder for the remaining 63% (Figure 3). In particular, among patients with organic disorders, we found 16 cases of IBD - 8 ulcerative colitis (UC) and 8 Crohn’s disease (CD); 9 parasitic or bacterial infections; 7 diverticular diseases; 1 microscopic colitis; 1 colorectal cancer, 1 CeD and 1 ischemic colitis. Ninety-one percent of patients with functional disorders fulfilled Rome III criteria for IBS, mainly IBS-D. Noteworthy, most of NLH patients with IBD and almost 20% of patients with IBS showed NLH with RRS (Figure 4).

Statistically significant differences between organic and functional conditions associated with s-NLH were found for sex (more women in the functional subset) and self-reported lactose intolerance (more common in organic disorders). On the contrary, there were no statistically significant differences in frequency of bowel habit alterations and metal contact dermatitis between organic and functional s-NLH patients. Also, we did not found a statistically significant correlation between NLH distribution and clinical symptoms (data not shown).

Symptomatic patients who underwent colonoscopy and did not show NLH [symptomatic patients without NLH (s-no-NLH)] were 214. Many of them complained of altered bowel habits (mostly constipation or mixed), and abdominal pain; 40% also reported haematochezia. In 28% of cases, colonoscopy revealed macroscopic inflammation (hyperaemia, erosions and ulcers) and biopsies were taken; none of the samples exhibited NLH at histological examination. Colon polyps were found and removed in 45% of s-no-NLH patients.

Regarding the final diagnosis, 34% of s-no-NLH patients were affected by organic diseases, while the remaining 66% had a functional condition (Figure 5). In particular, among patients with organic disorders, we found 5 cases of IBD (1 UC and 4 CD); 2 infectious colitis; 55 diverticular diseases; 12 abdominal adhesions; 3 colorectal cancers. Among patients with functional disorders, 80% fulfilled Rome III criteria for IBS, mostly IBS-C or IBS-M. No differences were found in terms of distribution of self-reported lactose intolerance and contact dermatitis between s-no-NLH patients with organic and functional conditions. Noteworthy, we found a statistically significant difference in mean age, being patients with organic disorders older than those with functional conditions. On the contrary, no difference for sex distribution was noted between the two subsets. Patients with functional disorders showed less frequently bloating and macroscopic inflammation at endoscopy.

Patients with NLH were significantly younger, had more often diarrhoea and bloating and less frequently constipation and colonic polyps vs patients without NLH. Moreover, NLH patients reported more frequently metal contact dermatitis and lactose intolerance vs patients without NLH, regardless the final diagnosis of functional or organic disorders. Stratifying all symptomatic subjects according to the final diagnosis, among those diagnosed with functional conditions, patients showing NLH were younger, more often female, and had a higher frequency of abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhoea, inflammation, metal contact dermatitis and self-reported lactose intolerance; on the contrary, they showed less frequently constipation, haematochezia, mixed bowel habits and colon polyps, compared with patients without NLH. Among patients with organic diseases, those showing NLH were also significantly younger, had more often diarrhoea, contact dermatitis and lactose intolerance, less frequently constipation and fewer polyps. No differences were noted for sex, abdominal pain, bloating, endoscopic signs of inflammation or haematochezia. Finally, NLH patients with organic conditions were more often diagnosed with IBD and infections, while those without NLH had a higher frequency of diverticular disease and abdominal adhesions; no differences were noted for colorectal cancer frequency (Table 2). We did not found a statistically significant difference in terms of clinical or endoscopic disease activity between IBD patients with or without NLH.

| Organic disorders | s-no-NLH | s-NLH | P value |

| Diverticular disease | 70% | 19% | < 0.05 |

| Colon cancer | 4% | 3% | NS |

| Infections | 3% | 24% | < 0.05 |

| IBD | 7% | 43% | < 0.05 |

| Abdominal adhesions | 16% | 0% | < 0.05 |

| Others | 0% | 12% | < 0.05 |

Among the 835 individuals who underwent colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening, 23 had NLH. Thus, the prevalence of NLH in asymptomatic adults was significantly lower compared to the frequency of NLH in symptomatic patients (3% vs 32%, P < 0.05).

Most a-NLH patients were female (78%), with a mean age of 57 ± 9 years. NLH was mainly diffuse in all colonic segments (87%) and only 1 case showed involvement of the terminal ileum. Polyps were detected and removed in 48% of patients. A mild asymptomatic diverticular disease was observed in 35% of cases; in only 2 patients with diverticula we noted signs of macroscopic inflammation. Metal contact dermatitis was reported by 44% of a-NLH. One of the cases complained of lactose intolerance. Comparing the a-NLH group with the remaining 812 asymptomatic individuals who underwent screening colonoscopy and did not show NLH (a-no-NLH), the latter ones were older (mean age 61 ± 9 years, P < 0.05), more frequently male (female 43%, P < 0.05) and had a statistically significant lower prevalence of self-reported contact dermatitis (5%, P < 0.05). The polyp detection rate did not significantly differ between the two groups (48% vs 64%, P > 0.05).

The present study assessed the frequency and gender distribution of colonic NLH, observed at WL and NBI endoscopy and histologically confirmed, in adults undergoing colonoscopy in a three-year period. The association between NLH and known diseases was also investigated.

The global prevalence of NLH was 10%. NLH was rare in asymptomatic subjects (3%). In particular, NLH was found mostly in asymptomatic women, who were younger than the relative control population and more often reported metal contact dermatitis. Conversely, NLH was a frequent finding in symptomatic patients, undergoing colonoscopy for IBS-type symptoms or suspected IBD (32%). Also among the symptomatic patients’ group, NLH was more frequent in young women, who often complained of metal contact allergies and lactose intolerance. As for clinical presentation, diarrhoea and bloating were more common, while constipation was rarer in NLH vs no-NLH patients. Diverticular disease and abdominal adhesions were more frequent in no-NLH cases, while NLH patients more often suffered from IBD or colonic infections and had fewer polyps, likely because of the younger age at presentation.

Overall, our results demonstrate that NLH of the lower gastrointestinal tract is a common endoscopic finding in symptomatic patients, in whom it might reflect a state of enhanced immunological activity. Indeed, it has been postulated that lymphoid hyperplasia results from a chronic activation of the gut immune system by antigenic triggers (i.e., allergens, pathogens, toxins), that lead to repetitive stimulation and eventual hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles. NLH might also develop in conditions of deregulation of the immune system, like in autoimmune diseases[17] or in immunodeficient subjects[18].

The association between food allergies and NLH has been already documented[12,33,34]. Conversely, to the best of our knowledge, there are no published data on the relationship between NLH and allergic contact allergy. Metal allergens, notably Ni, account for a significant proportion of contact sensitization[35]. It has been reported that about 15% of women and 2%-3% of men living in industrialized countries are Ni sensitive and may develop allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), a T cell-mediated inflammatory process of the skin induced by cutaneous absorption of an allergen in a previously sensitized individual. This gender difference is due to different rates of exposure of skin (from jewellery, leathers, etc.) to this substance. About 20%-30% of ACD patients also experiences systemic (headache, asthenia, itching), and gastrointestinal (bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhoea) symptoms after eating Ni-rich foods. This condition is known as “Systemic Contact Dermatitis” or “Systemic Ni Allergy Syndrome” (SNAS)[36]. Di Gioacchino et al[37], demonstrated that oral challenge with Ni, in women with SNAS, stimulates the immune system, inducing a maturation of T lymphocytes from virgin into memory cells, which accumulate in the intestinal mucosa. An increased frequency of delayed type hypersensitivity to metals has been reported in patients with connective tissue disease and fibromyalgia and it has been speculated that metal-specific T cell reactivity might be an etiological factor in the development of chronic immune-mediated disorders[38,39]. Noteworthy, Cazzato et al[40] demonstrated a higher prevalence of lactose intolerance in patients affected by SNAS vs controls (74.7% vs 6.6%, respectively); the authors argued that the Ni-induced pro-inflammatory status could temporary impair the brush border enzymatic functions, resulting in hypolactasia.

In our study, we observed a very high frequency of self-reported lactose intolerance and metal contact dermatitis in NLH patients. We can suppose that metal allergens might play a pivotal role in the development of lymphoid hyperplasia and hypolactasia. This could also account for the higher observed prevalence of NLH in women, given the increased frequency of Ni-sensitivity in female vs male sex.

Another interesting result of our study is the association between NLH and IBD. It is well known that IBD are characterised by an abnormal immunological response to environmental antigens, especially the enteric bacterial flora, in genetically susceptible individuals. Lymphoid follicles represent the main portal of entry for potential pathogens, and it has been suggested that aphthous ulceration in CD and UC originates in follicle-associated epithelium over the lymphoid follicles. In 2010, Krauss et al[6], compared the morphology of lymphoid follicles in CD, UC and control patients, in correlation to histological and immunohistochemical findings. In 15 out of 17 patients with the first manifestation of CD, they documented NLH with RRS. In some NLH with RRS early aphthous ulcers were seen. The authors concluded that lymphoid follicles with RRS probably represent an early sign of aphthous ulcers in CD and, thus, may be considered as early markers of first manifestation and flares in CD.

In our study, 43% of s-NLH were diagnosed as affected from IBD. Interestingly, in most cases of IBD, NLH was associated with RRS.

Finally, we observed for the first time an association between NLH and IBS[41]. Even if multiple advances have been made in the knowledge of IBS pathogenesis, its aetiology remains unknown. Probably, IBS is an “umbrella term”, which includes multiple conditions with common gastrointestinal symptoms, but different etiopathogenesis. Among the putative factors involved in the development of IBS, low-grade inflammation has raised growing interest in the last years. Indeed, IBS is more common in gastrointestinal diseases characterized by inflammation, such as CeD, IBD or after severe acute gastroenteritis[42-44]. Mucosal and systemic immune activation has been widely documented in patients with IBS, even in the absence of a previous major gastroenteritis event[45]. Mucosal inflammation is linked to increased mucosal permeability, enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia and higher tissue availability of serotonin, a key factor involved in the control of gut sensorimotor functions[46-48]. Furthermore, the possible link between low-grade inflammation and IBS has been suggested by the observation that adoptive transfer of mucosal biopsy supernatants evoked activation of sensory pain pathways[49,50] and abnormal enteric nervous system responses in recipient rodents[51]. Interestingly, these responses were reduced to a large extent by antagonism of immune-related factors[49-52]. The origin of low-grade inflammation in patients with IBS remains undetermined, but it is likely to be multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition[53,54], stress[55], atopy[56], abnormal intestinal microbiota[57], and higher mucosal permeability[46]. These data confirm the heterogeneity of IBS patients and point toward the necessity to find an objective biomarker of low-grade inflammation, to select those patients who could benefit most from anti-inflammatory therapy.

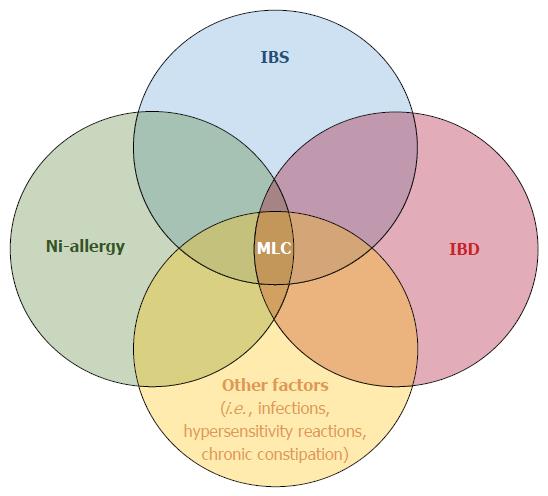

Our results suggest that NLH could be such a marker of low-grade inflammation in a conspicuous subset of IBS cases, in which a “minimal lesions colitis” (MLC) characterized by diffuse colonic NLH can be found. Notably, patients with NLH have some distinctive features within the IBS population: they are younger, more often female, and have a higher frequency of metal contact dermatitis, abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhoea, and unspecific inflammation. Moreover, 19% of patients with MLC had NLH associated with RRS; we might speculate that in these cases MLC could share common features with IBD.

Our work presents some limitations. Firstly, since this is a retrospective study, the asymptomatic population is not matched with the symptomatic population, because people undergoing colonoscopy for screening purposes are more often male and older, compared to patients with IBS-like symptoms or suspected IBD, who showed a higher prevalence of female and younger people. Moreover, we collected information about metal contact allergies and lactose intolerance from patients’ charts; such data were not available for all cases. Additionally, regarding the association between NLH and metal contact dermatitis, only a minority of subjects had performed patch tests and therefore we based our analysis on self-reported history of delayed hypersensitivity reactions to metals. Finally, only a minority of non-NLH patients underwent biopsy sampling during colonoscopy, while in most cases NLH was excluded on the base of endoscopic findings.

In conclusion, colonic NLH is rare in asymptomatic subjects, while it is a frequent finding in symptomatic patients, in whom it might reflect a state of enhanced immunological activity. We can speculate that colonic NLH represents an objective biomarker of low-grade inflammation in a subset of IBS patients, which might be triggered by metal contact reactions; moreover, colonic NLH with RRS might share common features with IBD, supporting the hypothesis that IBS and IBD might be part of the spectrum of the same disease (Figure 6).

Further studies are required to understand the etiopathogenetic mechanisms underlying colonic NLH in organic and functional conditions, its clinical implications and its possible link with IBD.

Colonic nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH) is considered a rare finding in adults. NLH can be asymptomatic or more rarely presents with gastrointestinal symptoms, like abdominal pain, chronic diarrhoea and bleeding and it has been reported in association with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, lymphoma, dysgammaglobulinemia, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, diversion colitis and food allergies.

Published literature includes case reports and small series of patients; whether this relates to endoscopy underreporting or to the true rarity of the condition is unclear.

This study sheds light on colonic NLH in adults, in terms of prevalence, gender-distribution and association with known diseases. The most relevant result of our study is the identification of NLH as a putative marker of low-grade inflammation in a subset of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) cases.

Diffuse colonic NLH could be a marker of low-grade inflammation in a conspicuous subset of IBS patients and could constitute a link between a subset of IBS cases and IBD.

The authors conclude that colonic NLH could be a marker of low-grade inflammation in a subset of patients with IBS. The point of view is interesting.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Republic of San Marino

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kamiya T S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Howat ABK, Douce G. The Royal College of Pathologists. In: Histopathology and cytopathology of limited or no clinical value. 2nd ed. London: RCPath, 2005. . |

| 2. | Hazewinkel Y, Dekker E. Colonoscopy: basic principles and novel techniques. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:554-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hirata I, Nakagawa Y, Ohkubo M, Yahagi N, Yao K. Usefulness of magnifying narrow-band imaging endoscopy for the diagnosis of gastric and colorectal lesions. Digestion. 2012;85:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cheon JH. Advances in the Endoscopic Assessment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Cooperation between Endoscopic and Pathologic Evaluations. J Pathol Transl Med. 2015;49:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Langman JM, Rowland R. The number and distribution of lymphoid follicles in the human large intestine. J Anat. 1986;149:189-194. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Krauss E, Konturek P, Maiss J, Kressel J, Schulz U, Hahn EG, Neurath MF, Raithel M. Clinical significance of lymphoid hyperplasia of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2010;42:334-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Olmez S, Aslan M, Yavuz A, Bulut G, Dulger AC. Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small bowel associated with common variable immunodeficiency and giardiasis: a rare case report. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2014;126:294-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Sharma M, Goyal A, Ecka RS. An unusual cause of recurrent diarrhea with small intestinal “polyposis”. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the small intestine. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:e8-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Iacono G, Ravelli A, Di Prima L, Scalici C, Bolognini S, Chiappa S, Pirrone G, Licastri G, Carroccio A. Colonic lymphoid nodular hyperplasia in children: relationship to food hypersensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:361-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Riddlesberger MM, Lebenthal E. Nodular colonic mucosa of childhood: normal or pathologic? Gastroenterology. 1980;79:265-270. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kokkonen J, Arvonen M, Vähäsalo P, Karttunen TJ. Intestinal immune activation in juvenile idiopathic arthritis and connective tissue disease. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36:386-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kokkonen J, Karttunen TJ. Lymphonodular hyperplasia on the mucosa of the lower gastrointestinal tract in children: an indication of enhanced immune response? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:42-46. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kokkonen J, Tikkanen S, Karttunen TJ, Savilahti E. A similar high level of immunoglobulin A and immunoglobulin G class milk antibodies and increment of local lymphoid tissue on the duodenal mucosa in subjects with cow’s milk allergy and recurrent abdominal pains. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13:129-136. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, Linnell J, Casson DM, Malik M, Berelowitz M, Dhillon AP, Thomson MA, Harvey P. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998;351:637-641. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Furlano RI, Anthony A, Day R, Brown A, McGarvey L, Thomson MA, Davies SE, Berelowitz M, Forbes A, Wakefield AJ. Colonic CD8 and gamma delta T-cell infiltration with epithelial damage in children with autism. J Pediatr. 2001;138:366-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gurkan OE, Yilmaz G, Aksu AU, Demirtas Z, Akyol G, Dalgic B. Colonic lymphoid nodular hyperplasia in childhood: causes of familial Mediterranean fever need extra attention. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:817-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Vossenkämper A, Fikree A, Fairclough PD, Aziz Q, MacDonald TT. Colonic lymphoid nodular hyperplasia in an adolescent. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:684-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Albuquerque A. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in the gastrointestinal tract in adult patients: A review. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:534-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Venkitachalam PS, Hirsch E, Elguezabal A, Littman L. Multiple lymphoid polyposis and familial polyposis of the colon: a genetic relationship. Dis Colon Rectum. 1978;21:336-341. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Molaei M, Kaboli A, Fathi AM, Mashayekhi R, Pejhan S, Zali MR. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in common variable immunodeficiency syndrome mimicking familial adenomatous polyposis on endoscopy. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:530-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bronen RA, Glick SN, Teplick SK. Diffuse lymphoid follicles of the colon associated with colonic carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kenney PJ, Koehler RE, Shackelford GD. The clinical significance of large lymphoid follicles of the colon. Radiology. 1982;142:41-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jones SE, Fuks Z, Bull M, Kadin ME, Dorfman RF, Kaplan HS, Rosenberg SA, Kim H. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. IV. Clinicopathologic correlation in 405 cases. Cancer. 1973;31:806-823. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Fernandes BJ, Amato D, Goldfinger M. Diffuse lymphomatous polyposis of the gastrointestinal tract. A case report with immunohistochemical studies. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1267-1270. [PubMed] |

| 25. | De Smet AA, Tubergen DG, Martel W. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the colon associated with dysgammaglobulinemia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:515-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Postgate A, Despott E, Talbot I, Phillips R, Aylwin A, Fraser C. An unusual cause of diarrhea: diffuse intestinal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in association with selective immunoglobulin A deficiency (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:168-169; discussion 169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kabir SI, Kabir SA, Richards R, Ahmed J, MacFie J. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management of diversion colitis: a review of current literature. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1088-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Venter C, Arshad SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58:327-349, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tokuhara D, Watanabe K, Okano Y, Tada A, Yamato K, Mochizuki T, Takaya J, Yamano T, Arakawa T. Wireless capsule endoscopy in pediatric patients: the first series from Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:683-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Colarian J, Calzada R, Jaszewski R. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the colon in adults: is it common? Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:421-422. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Kagueyama FM, Nicoli FM, Bonatto MW, Orso IR. Importance of biopsies and histological evaluation in patients with chronic diarrhea and normal colonoscopies. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2014;27:184-187. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3413] [Cited by in RCA: 3380] [Article Influence: 177.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Mansueto P, Iacono G, Seidita A, D’Alcamo A, Sprini D, Carroccio A. Review article: intestinal lymphoid nodular hyperplasia in children--the relationship to food hypersensitivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1000-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Carroccio A, Iacono G, Di Prima L, Ravelli A, Pirrone G, Cefalù AB, Florena AM, Rini GB, Di Fede G. Food hypersensitivity as a cause of rectal bleeding in adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:120-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Rietschel RL, Fowler JF, Warshaw EM, Belsito D, DeLeo VA, Maibach HI, Marks JG, Mathias CG, Pratt M, Sasseville D. Detection of nickel sensitivity has increased in North American patch-test patients. Dermatitis. 2008;19:16-19. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Di Gioacchino M, Ricciardi L, De Pità O, Minelli M, Patella V, Voltolini S, Di Rienzo V, Braga M, Ballone E, Mangifesta R. Nickel oral hyposensitization in patients with systemic nickel allergy syndrome. Ann Med. 2014;46:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Di Gioacchino M, Boscolo P, Cavallucci E, Verna N, Di Stefano F, Di Sciascio M, Masci S, Andreassi M, Sabbioni E, Angelucci D. Lymphocyte subset changes in blood and gastrointestinal mucosa after oral nickel challenge in nickel-sensitized women. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;43:206-211. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Stejskal V, Reynolds T, Bjørklund G. Increased frequency of delayed type hypersensitivity to metals in patients with connective tissue disease. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;31:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Stejskal V, Ockert K, Bjørklund G. Metal-induced inflammation triggers fibromyalgia in metal-allergic patients. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34:559-565. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Cazzato IA, Vadrucci E, Cammarota G, Minelli M, Gasbarrini A. Lactose intolerance in systemic nickel allergy syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:535-537. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313:949-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 629] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 73.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sainsbury A, Sanders DS, Ford AC. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with celiac disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:359-365.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Halpin SJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1474-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Dai C, Jiang M. The incidence and risk factors of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Barbara G, Cremon C, Carini G, Bellacosa L, Zecchi L, De Giorgio R, Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V. The immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:349-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Piche T, Barbara G, Aubert P, Bruley des Varannes S, Dainese R, Nano JL, Cremon C, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R, Galmiche JP. Impaired intestinal barrier integrity in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: involvement of soluble mediators. Gut. 2009;58:196-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Cremon C, Carini G, Wang B, Vasina V, Cogliandro RF, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Grundy D, Tonini M, De Ponti F. Intestinal serotonin release, sensory neuron activation, and abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1290-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Foley S, Garsed K, Singh G, Duroudier NP, Swan C, Hall IP, Zaitoun A, Bennett A, Marsden C, Holmes G. Impaired uptake of serotonin by platelets from patients with irritable bowel syndrome correlates with duodenal immune activation. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1434-1443.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Barbara G, Wang B, Stanghellini V, de Giorgio R, Cremon C, Di Nardo G, Trevisani M, Campi B, Geppetti P, Tonini M. Mast cell-dependent excitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:26-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 610] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Cenac N, Andrews CN, Holzhausen M, Chapman K, Cottrell G, Andrade-Gordon P, Steinhoff M, Barbara G, Beck P, Bunnett NW. Role for protease activity in visceral pain in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:636-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Buhner S, Li Q, Berger T, Vignali S, Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Schemann M. Submucous rather than myenteric neurons are activated by mucosal biopsy supernatants from irritable bowel syndrome patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:e1134-e1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Balestra B, Vicini R, Cremon C, Zecchi L, Dothel G, Vasina V, De Giorgio R, Paccapelo A, Pastoris O, Stanghellini V. Colonic mucosal mediators from patients with irritable bowel syndrome excite enteric cholinergic motor neurons. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:e1118-e1570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Zucchelli M, Camilleri M, Andreasson AN, Bresso F, Dlugosz A, Halfvarson J, Törkvist L, Schmidt PT, Karling P, Ohlsson B. Association of TNFSF15 polymorphism with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2011;60:1671-1677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Swan C, Duroudier NP, Campbell E, Zaitoun A, Hastings M, Dukes GE, Cox J, Kelly FM, Wilde J, Lennon MG. Identifying and testing candidate genetic polymorphisms in the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): association with TNFSF15 and TNFα. Gut. 2013;62:985-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Piche T, Saint-Paul MC, Dainese R, Marine-Barjoan E, Iannelli A, Montoya ML, Peyron JF, Czerucka D, Cherikh F, Filippi J. Mast cells and cellularity of the colonic mucosa correlated with fatigue and depression in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2008;57:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Vivinus-Nébot M, Dainese R, Anty R, Saint-Paul MC, Nano JL, Gonthier N, Marjoux S, Frin-Mathy G, Bernard G, Hébuterne X. Combination of allergic factors can worsen diarrheic irritable bowel syndrome: role of barrier defects and mast cells. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:75-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Simrén M, Barbara G, Flint HJ, Spiegel BM, Spiller RC, Vanner S, Verdu EF, Whorwell PJ, Zoetendal EG. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut. 2013;62:159-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 655] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 54.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |