Published online Jul 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i27.6268

Peer-review started: March 4, 2016

First decision: April 1, 2016

Revised: April 13, 2016

Accepted: May 4, 2016

Article in press: May 4, 2016

Published online: July 21, 2016

Processing time: 133 Days and 21 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the feasibility and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids.

METHODS: The outcome of ESD for 23 lesions with hemorrhoids (hemorrhoid group) was compared with that of 48 lesions without hemorrhoids extending to the dentate line (non-hemorrhoid group) during the same study period.

RESULTS: Median operation times (ranges) in the hemorrhoid and non-hemorrhoid groups were 121 (51-390) and 130 (28-540) min. The en bloc resection rate and the curative resection rate in the hemorrhoid group were 96% and 83%, and they were 100% and 90% in the non-hemorrhoid group, respectively. In terms of adverse events, perforation and postoperative bleeding did not occur in both groups. In terms of the clinical course of hemorrhoids after ESD, the rate of complete recovery of hemorrhoids after ESD in lesions with resection of more than 90% was significantly higher than that in lesions with resection of less than 90%.

CONCLUSION: ESD on lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids could be performed safely, similarly to that on rectal lesions extending to the dentate line without hemorrhoids. In addition, all hemorrhoids after ESD improved to various degrees, depending on the resection range.

Core tip: Recently, the feasibility and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) have been reported from different countries. However, ESD for lesions extending to the dentate line is technically difficult due to the anatomical features. This paper showed ESD on lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids was feasible and safe, similarly to that on rectal lesions extending to the dentate line without hemorrhoids and all hemorrhoids after ESD improved to various degrees, depending on the resection range.

- Citation: Tanaka S, Toyonaga T, Morita Y, Hoshi N, Ishida T, Ohara Y, Yoshizaki T, Kawara F, Umegaki E, Azuma T. Feasibility and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for lower rectal tumors with hemorrhoids. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(27): 6268-6275

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i27/6268.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i27.6268

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a standard therapy for gastric neoplasms. Recently, ESD has been applied for superficial colorectal neoplasms and the number of publications about it has been increasing[1-3]. In addition, the feasibility and safety of this procedure have been reported from both Asia and Western countries[4,5]. However, ESD for lesions extending to the dentate line is technically difficult because these lesions sometimes have severe fibrosis[6], and the lumen is narrow due to the anal sphincter. Moreover, in this area, there are often coexisting hemorrhoids. For lesions with hemorrhoids, the maintenance of a good endoscopic view is not easy, and the management of large hemorrhoid vessels makes ESD increasingly difficult. However, ESD for lower rectal lesions should be considered if possible because surgery can result in a permanent colostomy or rectal dysfunction, and the patients’ quality of life is tremendously affected. To the best of our knowledge, the feasibility of ESD for rectal lesions with hemorrhoids has not been fully studied. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the feasibility and safety of ESD for lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids and the clinical course of hemorrhoids thereafter.

A total of 1485 colorectal neoplasms in 1357 patients were treated with ESD at Kobe University Hospital and Kishiwada Tokushukai Hospital between April 2005 and May 2014. The inclusion criteria for colorectal ESD were (1) lesions over 20 mm in size; (2) lesions with scars due to previous endoscopic treatment or biopsies; (3) local recurrent lesion after previous endoscopic or surgical resection; and (4) invasive carcinoma with slight submucosal invasion (< 1000 μm from the muscularis mucosa) estimated by conventional endoscopic and magnification chromoendoscopic examinations according to previous reports[7-9]. Among these lesions, 23 lesions coexisted with hemorrhoids. The presence of hemorrhoids was defined as the endoscopic finding that vessels in the area around the anus and rectum were clearly swollen and elevated above the surrounding mucosal level. All hemorrhoids diagnosis was performed by two endoscopists (Tanaka S and Ohara Y). When their diagnosis was different, it was confirmed afterward by two endoscopists. The outcome of ESD for the lesions with hemorrhoids (hemorrhoid group) was compared with that of 48 lesions without hemorrhoids extending to the dentate line (non-hemorrhoid group) during the same study period. The positional relationship between the lesion and the dentate line was confirmed using an endoscope. The size of the lesion was confirmed by pathological assessment. The morphological types of colorectal lesions were classified as lateral spreading tumor granular type (LST-G), lateral spreading tumor non-granular type (LST-NG), protruding type and depressed type. This is a retrospective study, and we retrospectively reviewed the medical records including patient characteristics, details of endoscopic treatment and pathological features of the resected lesions.

Four endoscopists carried out the procedure. They were all well-trained endoscopists with substantial experience of ESD (more than 100 cases). ESD was carried out with Flush knife (DK2618JN10; FUJIFILM) or Flush knife BT (DK-2618JN; FUJIFILM) through a conventional single-channel endoscope (CF-240I, CF-260AI, GIF-Q260J; Olympus Medical Systems). The Flush knife and Flush knife BT used were 1.5 mm in length. A transparent hood (D-201-11084; Olympus, 16675; TOP) was mounted on the tip of the endoscope to maintain a clear operative field. An ICC 200 or VIO 300D (ERBE Elektromedizin, GmbH, Tübingen) was used as the power source for electrical cutting and coagulation. The procedure time was measured from the first submucosal saline injection to lifting of the target lesion to the end of the procedure (when en bloc resection was achieved), using a stopwatch. The procedure speed, the area of mucosa dissected per minute (mm2/min), was calculated by the area of the resected specimen divided by the procedure time. The approximate oval area (mm2) of the resected specimen was calculated as follows: 3.14 × 0.25 × long axis × minor axis[10].

Submucosal injection: There are sensory nerves in the squamous epithelium below the dentate line. Thus, when submucosal injection was performed at the anal side, to prevent pain, 1% lidocaine (100 mg/10 mL) diluted 1:1 with hyaluronic acid solution was used as submucosal injection solution.

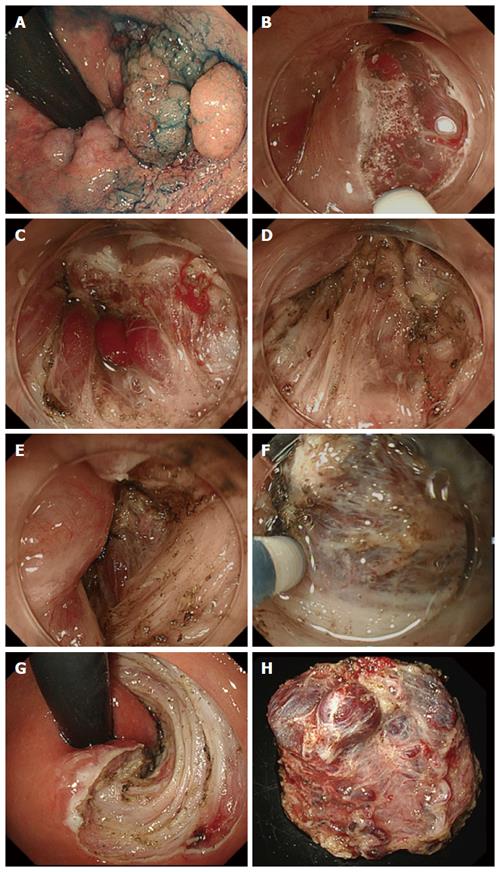

Mucosal incision: To avoid bleeding, a shallow mucosal incision was performed and the vessels were exposed while inflicting as little damage as possible (Figure 1A-C). The exposed vessels were coagulated using hemostatic forceps.

Submucosal dissection: At the anal canal area, the submucosal layer is connected tightly with mucosal epithelium by submucosal muscle strands (musculus submucosa ani), which is derived from longitudinal muscle of rectum (Figure 1D). Dissociation of this submucosal muscle strands completely and reaching just above the muscularis propria layer are very important (Figure 1E). The submucosal dissection was performed just above the muscularis propria layer and the penetrating vessels were handled using an electro-knife itself or hemostatic forceps (Figure 1F-H).

Postoperative bleeding was defined as: (1) requiring endoscopic hemostatic treatment; (2) when the total hemoglobin dropped by more than 2 g/dL compared with the last preoperative level; or (3) cases of massive melena after ESD with no other apparent source of bleeding. Perforation was diagnosed by endoscopic findings during the endoscopic treatment, or was diagnosed by the presence of free air on abdominal plain radiography or computed tomography

All patients were informed of the risks and benefits of ESD and provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Kobe University Hospital and Kishiwada Tokushukai Hospital.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Proportions of categorical variables were compared using two-sided Fisher’s exact test and χ2 test. Continuously distributed variables were compared using Student’s t-test, and non-continuous variables were assessed using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

In this study, 23 lesions were classified into the hemorrhoid group and 48 into the non-hemorrhoid group. Characteristics of the patients and the lesions are shown in Table 1. The median tumor size (range) in the hemorrhoid group was 53 (6-158) mm and that in the non-hemorrhoid group was 52 (7-155) mm. Histological examination revealed that there were 7 cases of adenoma, 15 of Tis-T1b cancer and 1 of T1b or deeper cancer in the hemorrhoid group, and 9 cases of adenoma, 34 of Tis-T1a and 5 of T1b or deeper cancer in the non- hemorrhoid group. These data showed no significant difference between the two groups.

| Hemo group | Non-Hemo group | P value | |

| Patients | 23 | 48 | |

| Lesions | 23 | 48 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 9 | 17 | 0.9 |

| Female | 14 | 31 | |

| Age (yr), median (range) | 69 (48-79) | 65 (40-87) | 0.4 |

| Morphological type | |||

| LST-G | 17 | 34 | 1.0 |

| LST-NG | 0 | 1 | |

| Protruding | 6 | 13 | |

| Tumor size (mm), median (range) | 53 (6-158) | 52 (7-155) | 0.81 |

| Specimen size (mm), median (range) | 65 (28-165) | 62(25-180) | 0.9 |

| Histology | |||

| Adenoma | 7 | 9 | 0.84 |

| Tis-T1a | 15 | 34 | |

| T1b or deeper | 1 | 5 |

Table 2 shows a summary of the outcomes and adverse events of the treated lesions. The median operation time (range) in the hemorrhoid group was 121 (51-390) min, and it was 130 (28-540) min in the non-hemorrhoid group, which were not significantly different. Median procedure speed (range) in the hemorrhoid group was 0.18 (0.05-0.47) mm2/min, and it was 0.20 (0.02-0.57) mm2/min in the non-hemorrhoid group. These results were not significantly different.

| Hemo group | Non-Hemogroup | P value | |

| Operation time (min), median (range) | 121 (51-390) | 130 (28-540) | 0.98 |

| Procedure speed (mm2/min), median (range) | 0.18 (0.05-0.47) | 0.20 (0.02-0.57) | 0.46 |

| En bloc resection | 22 (96) | 48 (100) | 0.32 |

| Curative resection | 19 (83) | 43 (90) | 0.32 |

| Adverse events | |||

| Perforation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

The en bloc resection rate and the curative resection rate in the hemorrhoid group were 96% and 83%, and they were 100% and 90% in the non-hemorrhoid group, respectively. These rates were not significantly different between the two groups. In terms of adverse events, perforation and postoperative bleeding did not occur in both groups.

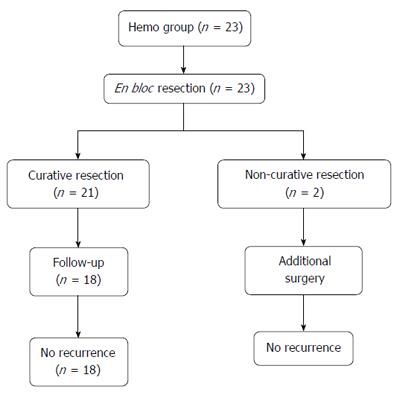

Of the 23 patients, in 21 patients, the result was curative resection. Of the 2 patients with non-curative resection, both underwent surgical treatment. After surgical resection, neither case had recurrence during a median follow-up period of 27.5 mo (range 12-43 mo). Of the 21 patients with curative resection, 3 patients did not receive follow-up colonoscopy for personal reasons, and 18 patients underwent surveillance colonoscopy. Among them, there were no cases of recurrence during a median follow-up period of 36 mo (range 2-99 mo) (Figure 2).

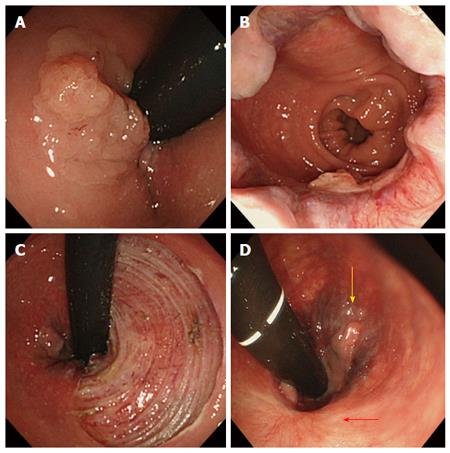

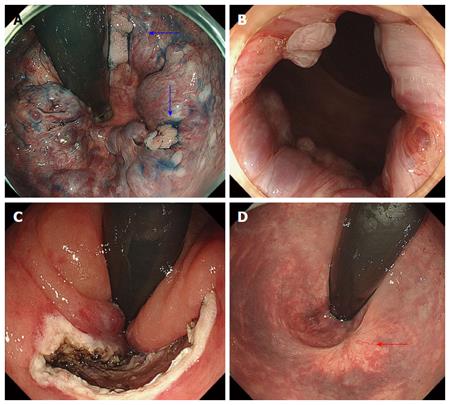

Among the 23 lesions with hemorrhoids, 22 lesions were classified into Goligher classification type 1 and 1 lesion into Goligher classification type 2. There were no patients in Goligher classification type 3 or 4. In terms of the clinical course of hemorrhoids after ESD, among 13 lesions with resection of less than 90% of the circumference, 11 lesions partially regressed (Figure 3) and complete recovery was achieved for 2 lesions (Figure 4). Among 5 lesions with resection of more than 90% including 2 lesions resected circumferentially, complete recovery of all hemorrhoids was achieved. The rate of complete recovery of hemorrhoids after ESD in lesions with resection of more than 90% was significantly higher than that in lesions with resection of less than 90% (P < 0.01). One patient with Goligher classification type 2 had complained anus pain from hemorrhoids, but the symptom completely disappeared after ESD. There were no lesions for which the hemorrhoids worsened.

Lower rectal lesions extending to the dentate line are considered difficult to remove endoscopically because of the narrow lumen, the risk of bleeding from the rectal venous plexus, and anal pain through sensory nerves in the anoderm[6]. The recent development of devices and techniques for ESD has allowed the performance of en bloc resection of technically difficult lesions[10-13]. Several reports have described the safety and efficacy of ESD of rectal lesions extending to the dentate line[6,14]. However, lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids seemed to be technically more difficult. In lower rectal lesions, the quality of life (QOL) of patients is greatly affected by the treatment method. Surgery is preferably avoided in terms of the patient’s QOL after treatment due to the risk of a permanent colostomy and rectal dysfunction. Transanal resection (TAR) for lower rectal tumors is useful with few complications; however, local recurrence has been reported in 23% to 31% of cases[15-17]. Kiriyama et al[15] reported ESD to be more effective than TAR for treating noninvasive rectal tumors, with a lower recurrence rate and a shorter hospital stay, despite a longer procedure time. Moreover, Nam et al[18] reported Overall direct medical costs were significantly lower for ESD than for TAR in the treatment of rectal tumors. Therefore, ESD seems to be the most non-invasive and reliable treatment for lower rectal lesions. Furthermore, if ESD could be performed on lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids, it could be a better treatment in terms of avoiding recurrence and improving patient’s QOL.

In previously reported studies, esophageal cancer with esophageal varices could be resected endoscopically by the eradication of varices using endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) or endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) before endoscopic resection[19-22]. Superficial esophageal neoplasms can be removed endoscopically even if they are located on varices. As varices have a steady blood flow from the anal to the oral side, EVL or EIS can be carried out on the anal side away enough from the tumor, so that the secondary shrinkage and fibrosis do not affect the endoscopic tumor resection. However, since the hemorrhoidal plexus is controlled by the superior rectal artery, middle rectal artery and inferior rectal artery, the blood supply is more complicated than for esophageal varices. Sclerotherapy or ligation therapy has to be performed in the proximity of the tumor, and banding or fibrosis after treatment makes ESD more difficult. Thus, ESD for lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids has to be carried out without pre-treatment.

In previous reports, technical points of ESD for lower rectal lesions extending to the dentate line have been described as follows: (1) local anesthesia to prevent anal pain before the submucosal injection of hyaluronic acid; (2) a shallow peripheral mucosal incision to prevent bleeding; and (3) appropriate handling of the blood vessels with hemostatic forceps[6]. The strategy of ESD for lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids is almost the same as that described above in our institute. However, we pay particular attention to the depth of mucosal incision and the appropriate level of submucosal dissection. The creation of sufficient space between mucosa and submucosal vessel by injecting hyaluronic acid solution and the performance of a shallow mucosal incision without hemorrhoid injury are necessary to prevent bleeding. The submucosal layer at the anal canal is tightly connected to the mucosal epithelium. Cutting the submucosal layer completely and reaching just above the muscularis propria are important. In addition, hemorrhoid vessels penetrate the muscle layer vertically and hemorrhoids develop at the level of the middle submucosal layer. If the submucosal dissection is performed at the level just above the muscularis propria layer, the only penetrating vessels have to be processed and the source of blood supply into hemorrhoids could be shut off. If the dissecting level is too shallow or kept at the middle submucosal layer, many hemorrhoid vessels would be exposed and it would require a substantial amount of time to process them. In addition, if complete handling of vessels to shut off the blood flow were not performed, hemorrhoids might not be improved after ESD. Therefore, the maintenance of an appropriate dissection level is important to perform ESD safely and effectively, not only to remove the tumor, but also to make the hemorrhoids disappear. By following the technical tips, a higher rate of en bloc resection without adverse events was achieved in this study.

There were no cases in which hemorrhoids worsened after ESD. All hemorrhoids after ESD were improved to various degrees, depending on the resection range. In all cases that required resection of more than 90% of the circumference, the hemorrhoids completely disappeared. Even in lesions with resection of less than 90% of the circumference, the hemorrhoids were completely improved in 2 of 13 lesions. One of them had severe hemorrhoids (Goligher classification type 2); however, in this case, complete recovery was achieved by resection of only half the circumference (Figure 4). The effectiveness of ESD for hemorrhoids can be explained by two mechanisms. One is that it allows the cutting and shutting off of blood vessels feeding into the hemorrhoids. The other is fibrosis after ESD, which could have a similar effect to APC after EIS or para-sclerosing therapy for esophageal varices.

In terms of the outcomes of ESD in the hemorrhoid group and the non-hemorrhoid group, although the hemorrhoid group seemed to be associated with greater technical difficulty than the non-hemorrhoid group, there were no significant differences in operation time, procedure speed, en bloc resection rate and adverse events. This result should not be considered to indicate that the technical difficulty was the same with or without the presence of hemorrhoids. In our study, all ESDs were performed by endoscopists with sufficient experience. It should be noted that ESD is technically difficult and requires adequate experience and advanced skills, so it should be performed by well-trained endoscopists.

There were no cases of recurrence during the follow-up period. This was presumably significantly contributed to by the achievement of a high en bloc resection rate. However, six cases could be followed up within only 12 mo and the follow-up periods were thus insufficient, so further investigation is necessary.

In conclusion, ESD on lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids could be performed safely, similarly to that on rectal lesions extending to the dentate line without hemorrhoids. In addition, all hemorrhoids after ESD could be improved to various degrees depending on the resection range. ESD for lower rectal lesions could be a good indication for lower rectal lesions in spite of the presence of hemorrhoids.

Recently, the feasibility and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) have been reported from different countries. However, ESD for lesions extending to the dentate line is technically difficult due to the anatomical features. Moreover, if the lesion coexists with hemorrhoids, ESD might be increasingly difficult.

The prior report described that ESD for lesions extending to the dentate line is technically difficult due to severe fibrosis. In this area, there are often coexisting hemorrhoids. This study evaluated the feasibility of ESD for rectal lesions with hemorrhoids.

In this study, ESD on lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids could be performed safely, similarly to that on rectal lesions extending to the dentate line without hemorrhoids. In addition, all hemorrhoids after ESD could be improved to various degrees depending on the resection range.

This study suggested that ESD for lower rectal lesions could be a good indication for lower rectal lesions in spite of the presence of hemorrhoids.

The author of this paper evaluated that ESD on lower rectal lesions with hemorrhoids could be performed safely, similarly to that on rectal lesions extending to the dentate line without hemorrhoids.

P- Reviewer: Balta AZ, Leo JM, Scheidbach HJ S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Nakajima T, Saito Y, Tanaka S, Iishi H, Kudo SE, Ikematsu H, Igarashi M, Saitoh Y, Inoue Y, Kobayashi K. Current status of endoscopic resection strategy for large, early colorectal neoplasia in Japan. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3262-3270. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y, Hotta K, Sakamoto N, Ikematsu H, Fukuzawa M, Kobayashi N, Nasu J, Michida T. A prospective, multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1217-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 591] [Cited by in RCA: 593] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Iacopini F, Bella A, Costamagna G, Gotoda T, Saito Y, Elisei W, Grossi C, Rigato P, Scozzarro A. Stepwise training in rectal and colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection with differentiated learning curves. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1188-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yoon JY, Kim JH, Lee JY, Hong SN, Lee SY, Sung IK, Park HS, Shim CS, Han HS. Clinical outcomes for patients with perforations during endoscopic submucosal dissection of laterally spreading tumors of the colorectum. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:487-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Probst A, Golger D, Anthuber M, Märkl B, Messmann H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in large sessile lesions of the rectosigmoid: learning curve in a European center. Endoscopy. 2012;44:660-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakadoi K, Tanaka S, Hayashi N, Ozawa S, Terasaki M, Takata S, Kanao H, Oka S, Chayama K. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal tumor close to the dentate line. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:444-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Nakamura M, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Ono S, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Yamamichi N, Tateishi A. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal epithelial neoplasia. Endoscopy. 2006;38:493-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tanaka S, Oka S, Kaneko I, Hirata M, Mouri R, Kanao H, Yoshida S, Chayama K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: possibility of standardization. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Muraki Y, Ono S, Yamamichi N, Tateishi A, Oka M, Ogura K. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial neoplasms in 200 consecutive cases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:678-683; quiz 645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Toyonaga T, Man-I M, Fujita T, Nishino E, Ono W, Morita Y, Sanuki T, Masuda A, Yoshida M, Kutsumi H. The performance of a novel ball-tipped Flush knife for endoscopic submucosal dissection: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:908-915. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Toyonaga T, Nishino E, Man-I M, East JE, Azuma T. Principles of quality controlled endoscopic submucosal dissection with appropriate dissection level and high quality resected specimen. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:362-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tanaka S, Toyonaga T, Morita Y, Hoshi N, Ishida T, Ohara Y, Yoshizaki T, Kawara F, Azuma T. Feasibility and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for large colorectal tumors. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:223-228. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kanzaki H, Ishihara R, Ohta T, Nagai K, Matsui F, Yamashina T, Hanafusa M, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Takeuchi Y. Randomized study of two endo-knives for endoscopic submucosal dissection of esophageal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1293-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Imai K, Hotta K, Yamaguchi Y, Kakushima N, Tanaka M, Takizawa K, Kawata N, Matsubayashi H, Shimoda T, Mori K. Preoperative indicators of failure of en bloc resection or perforation in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: implications for lesion stratification by technical difficulties during stepwise training. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:954-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kiriyama S, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Nakajima T, Mashimo Y, Joeng HK, Moriya Y, Kuwano H. Comparing endoscopic submucosal dissection with transanal resection for non-invasive rectal tumor: a retrospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1028-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sakamoto GD, MacKeigan JM, Senagore AJ. Transanal excision of large, rectal villous adenomas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:880-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Winburn GB. Surgical resection of villous adenomas of the rectum. Am Surg. 1998;64:1170-1173. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Nam MJ, Sohn DK, Hong CW, Han KS, Kim BC, Chang HJ, Park SC, Oh JH. Cost comparison between endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal endoscopic microsurgery for the treatment of rectal tumors. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015;89:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Hsu WH, Kuo CH, Wu IC, Lu CY, Wu DC, Hu HM. Superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma over esophageal varices treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:833-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Künzli HT, Weusten BL. Endoscopic resection of early esophageal neoplasia in patients with esophageal varices: how to succeed while preventing the bleed. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E631-E632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ciocîrlan M, Chemali M, Lapalus MG, Lefort C, Souquet JC, Napoléon B, Ponchon T. Esophageal varices and early esophageal cancer: can we perform endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)? Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mitsuishi T, Goda K, Imazu H, Yoshimura N, Kazihara M, Saruta M, Takagi I, Kato T, Tajiri H, Ikegami M. Superficial esophageal carcinomas on esophageal varices treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection after intravariceal endoscopic injection sclerotherapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;55:2189-2196. |